Meeting children's needs when the family environment isn't always "good enough": A systems approach

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

May 2013

Debbie Scott

Download Policy and practice paper

Key messages

-

For some at-risk children, out-of-home care is the best option. For others - especially those who live in family environments that are safe most of the time, but which occasionally become unsafe - intensive home-based family support may be preferable.

-

Judging whether a family environment is "safe enough" can be difficult, especially considering there is no definitive description of what constitutes a safe environment for children.

-

The systems approach has been advocated by a number of child protection experts. This approach emphasises that while it is not possible to eliminate human error or guarantee child safety, the consequences of errors and dangers can be minimised by establishing systems that recognise that they will inevitably occur.

-

If the strengths in the family environment are encouraged, and if risks are minimised using a systems approach, it may be possible to provide safety for children who live in variable family environments.

Overview

This paper provides a theoretical basis to using a systems approach to working with vulnerable and high-risk families where children's needs are generally being met, but where parenting is at times not "good enough" or even unsafe.

Practical tools to aid the implementation of a systems approach to intensive home based support for these families are provided in three accompanying practice resources. These resources (developed by Marie Iannos and Greg Antcliff, 2013) provide some guidance in the use of motivational interviewing, planning for safety with at-risk families and parent skills training:

- Parent-skills training in intensive home-based family support programs

- Planning for safety with at-risk families: Resource guide for workers in intensive home-based family support programs

- The application of motivational interviewing techniques for engaging "resistant" families

Key messages

Introduction

Families - whether safe or unsafe - are pivotal in shaping child development. The United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRoC) declared that for a child to develop to his or her best capabilities he or she "should grow up in a family environment in an atmosphere of happiness, love and understanding" (United Nations, 1989, para 8). Similarly, The National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children (Council of Australian Governments [COAG], 2009) recognises the CRoC, and Supporting Outcome 1 reiterates: "Children live in safe and supportive families and communities" (p. 15).

While the ideal situation is that children grow up loved and nurtured within their family environments, the circumstances for many children are less than ideal. For those children whose families do not provide a healthy and supportive environment, and particularly for those who are at risk of harm, it may be necessary for the child protection system to intervene in the best interests of the child. For some children this may involve removal from the home. For others, where children's needs are generally being met, the best option may be to support the parents to care for their child in their home environment and develop a "safety net" for those times when parenting is not "good enough" or the home environment becomes unsafe.

A caseworker has been working with a family where alcohol misuse led to ongoing heated verbal arguments and a physical altercation between the parents that resulted in a brief period of hospitalisation for the mother,. Both parents have willingly engaged in sessions over a number of months with the caseworker and are able to identify the times at which their behaviour is unhealthy for their three children. Both parents have also managed to gradually restrict their alcohol intake, particularly when the children are present. The caseworker also provided tools and support to change communication patterns between the parents resulting in improved communication skills.

The father recently lost his car-manufacturing job and accepted a fly-in-fly-out position at a mine in remote Western Australia. The caseworker continues to engage the parents with issues of household hygiene, and the mother occasionally drinks to excess while dad is away, however the environment for the children is deemed "safe enough" to warrant the children remaining in the home with support. However, the situation now arises that when the father returns for his 7-day "off shift" once every 6 weeks, both parents occasionally drink to excess and patterns of verbal abuse have returned and infrequently have escalated to pushing and shoving between them.

When does safe become unsafe?

No clear description of what constitutes a "safe" environment for children appears in the literature. There is a general understanding that, at a minimum, children are provided with a home where environmental risks (including unsanitary conditions and injury risks) are minimised, where their physical (food, personal hygiene, medical care), emotional (support, nurturing) and developmental (education) needs are met and they are free from abuse and neglect, including family violence (Iannos & Antcliff, 2013b)

In order to understand if children are at risk or have been abused or neglected, a clear definition of what constitutes abuse or neglect is needed (Davies & Ward, 2012). And in determining what actions are required to protect children, child protection practitioners are required to make judgements on what constitutes a safe environment for children.

Practitioners are required, under most state legislation, to base child wellbeing decisions on the risk of harm or significant harm that is occurring or may occur to the child. The assessment of the environment will rely on a judgement about harm and how the environment may contribute to the risk of harm for the child. An environment with drugs and drug paraphernalia, where criminal activity takes place or where potentially dangerous persons - for example, those who may be intoxicated, high, or violent - are commonplace, could deemed to be unsafe, regardless of whether or not harm has occurred (Fallon, Trocmé, & Maclaurin, 2011). Parental alcohol abuse, domestic violence, poor or limited parenting capacity, and mental health issues may also contribute to an unsafe environment, often through affecting the ability of the parent to respond to children's needs (Bromfield, Lamont, Parker, & Horsfall, 2010; Lamont & Bromfield, 2009). Other contributors to an unsafe environment may include inadequate housing, financial distress, social isolation and dispossession (Darlington, Healy, & Feeney, 2010). There is increasing recognition of the role of community in providing for the wellbeing of children.

Positive and negative factors in the environment impacting children's outcomes

Healthy development in children is complex - with an interaction between social environment and child and parent characteristics. Family is important in helping children to develop a sense of self and of themselves as an individual (Weeks & Quinn, 2000). Where children have positive and strong relationships with their parents, even in the face of other adversity, they appear to have improved mental health outcomes in later life (Price-Robertson, Smart, & Bromfield, 2010). This suggests that a healthy and safe environment for children is as much about what is present as what is lacking.

There is strong evidence that the effects of child maltreatment are detrimental to children and that these effects carry over into adulthood. These can include poorer mental health outcomes, substance abuse, chronic disease and criminal behaviour (Gilbert et al., 2009).

It is important to note that the severity, frequency, duration, type of maltreatment and relationship of the perpetrator to the child, as well as the presence of protective factors in the child's life, influence the consequences of maltreatment. The consequences of maltreatment are most detrimental for those who experience chronic or multi-type maltreatment (Higgins & McCabe, 2000; Lamont & Bromfield, 2010). These are all important considerations in assessing the risk of a child who is exposed to or living in an unsafe environment. It is important that child development doesn't occur in isolation, a child's ability to grow and develop and to cope with their environment is related to family and peer relationships and the environment where these occur (Bronfenbrenner, 1977, 1986). Support may come from outside the family, from friends and neighbours, teachers, sport coaches or other adults in the child's environment. Some children are more resilient than others. Resiliency is complex and influenced by other supports and protective factors at individual, family and community levels. Protective factors may exist at each level and may differ according to a child's developmental stage, the type of adversity (Hunter, 2012) and how accessible those protective factors are if the child's needs change.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has adapted Bronfenbrenner's ecological model to understand how individual, relationship, community and societal factors interact and result in violence (See Figure 1). This model is particularly useful in understanding that while factors at different levels play a role in determining the likelihood that a child will experience maltreatment, each level sits in, and is influenced by the levels that surround it. Furthermore, the influence may be a "risk" or a "protective" factor, modifying the likelihood and consequences of maltreatment.

- At the individual level, factors related to the biology of the person (e.g., congenital disability) or personality and behavioural factors (e.g., impulsivity) may influence the likelihood of violence.

- Relationships with friends, family members and peers may increase or minimise the risk of maltreatment. For example, living in a home with a violent parent increases the risk of abuse or associating with a group of friends who engage in risky behaviours.

- The community also plays a role in child development and risk of maltreatment in the context of where relationships and individual factors sit. Community organisations like schools and neighbourhoods may contribute to safety or increase risk if they are characterised by individuals who are associated with violent behaviour, drug abuse or high levels of unemployment and poverty, for instance.

- Finally, all of these factors are influenced by the society in which they sit. Health, educational, economic and social policies that support social inequality, high levels of violence, and tolerance of these factors will result in a different context than a society where support is provided to minimise levels of inequality and where policies are intolerant of violence in the family and between individuals (Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lorenzo, 2002).

Figure 1: Ecological model for risk factors associated with maltreatment

Source: Krug et al. (2002, p.12)

Assessing risk in unsafe environments

Many child protection systems rely on the use of assessment tools to determine the risks in a family environment. These tools are designed to assist in decision-making processes and to predict future risk to children. The assumption is that, if the tools are used appropriately, it is possible to make good decisions about those children and families where state intervention is most needed to protect the child (Price-Robertson & Bromfield, 2011).1 According to Munro (2010), working within these standardised frameworks has made it more difficult to "provide the flexible and sensitive response that match the wide variety of needs and circumstances that are presented" (p. 7) and the focus becomes more on "a concern with doing things right versus a concern for doing the right thing" (p. 14).

Child protection work is inherently uncertain (Munro, 2010). While many tools exist to facilitate prediction of risk, that predication is difficult and should also involve professional judgement (Price-Robertson & Bromfield, 2011). An informed professional judgement based on the broad social context of the child and the family will often require collaboration from a number of agencies and professions (Nair, 2012). These agencies may include therapeutic services for children, early intervention, general and intensive family support, health, mental health, disability and family welfare services, as well as police and education (Darlington et al., 2010) and serve to meet the hierarchy of needs via implementation in an ecological framework.

In Munro's (2010) review of the British Child Protection System, she described the responsibilities associated with the risk assessment process:

In assessing the value of leaving the child in the same situation, professionals have to consider a balance of possibilities: to estimate how harmful it will be, to consider whether it might escalate and cause very serious harm or death. They also need to consider whether resources are locally available so that families can be helped to provide safer care and estimate how effective such interventions are likely to be. (p. 21)

Risk assessment in child maltreatment is a necessarily complex process. All assessments are subjective, social processes that require the consideration of the role of the child, the parent and the family within the broader social context. However, there is no definition or standard of what constitutes adequate parenting (Budd, 2001). Issues of accessibility to services and/or resources must also be considered - for some families, informal networks and services may be workable; for others, a more formalised approach may be required. This may be particularly true in areas where there are few services available due to remoteness. Furthermore, any risk assessment for child maltreatment purposes will involve some degree of an attempt to "predict the future" for what will happen for the child and family under assessment. Determining the type of harm a child is likely to face in an unsafe environment further complicates the assessment of an unsafe environment. Some types of maltreatment are more easily identified than others. For instance, sexual and physical abuse may be more obvious than emotional abuse or neglect, as emotional abuse and neglect often occur over time and in circumstances that, while not optimal, may not reach a threshold for tertiary intervention (Davies & Ward, 2012, p. 20). Research has shown that the focus should be on early intervention and the prevention of harm rather than tertiary involvement (and removal from the family) for optimal wellbeing (Darlington et al., 2010).

The risk factors for child maltreatment often involve domestic violence, mental health issues, substance and/or alcohol abuse and disability and are interwoven with broader social and economic disadvantage (Bromfield et al., 2010). Hence, addressing only one risk factor (i.e., substance abuse but not domestic violence or over crowded living conditions) or dealing with a problem at only one ecological level (i.e., removing a violent older adult brother or sister from a home environment but remaining in a school where gang activity is common) may not result in providing a safe enough environment for a child. However, having a parent who is willing, able and motivated enough to intervene on behalf of the child, a safety plan, and intensive, home-based family support that is established in conjunction with a case worker to facilitate, can make the difference between a child remaining at home in a safe enough environment or being removed and placed in out-of-home care (Hilferty et al., 2010; Tully, 2008).

1 For additional information on risk assessment see: Risk Assessment Instruments in Child Protection.

A systems approach to child safety and wellbeing

The National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020 recommends and promotes a public health approach to child protection. It lists "Joining Up Service Delivery" as a priority, and recommends a partnership approach to keeping Australia's children safe and well. A public health approach can be applied to settings as well as populations, so is suited to the ecological model of development and child maltreatment. Furthermore, a systems approach to child protection, as used by Munro in the review of the British Child Protection System (Munro, 2009), can be considered alongside the ecological model of child protection as a framework for keeping children safe.

While child protection has typically been seen as the responsibility of state-based child statutory authorities, Bronfrenbrenner's framework (1977) demonstrated that child wellbeing extends beyond statutory authorities and requires a collaborative effort between agencies, social workers, para-professionals, service providers, communities, families, and individuals. This is reiterated in the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020 by the declaration that "protecting children is everyone's business".

Reason's (2000) explanation of the systems approach assumed that human error is likely to occur and accepted human fallibility - people make mistakes. He suggested that errors are the result of a failure of systems rather than the cause of failure. According to Reason, errors should be expected and a system designed to minimise the impact of those errors rather than a focus on assigning blame to the individual who made the error. He goes on to say that "we cannot change the human condition, we can change the conditions in which humans work" (Reason, 2000, p. 394).

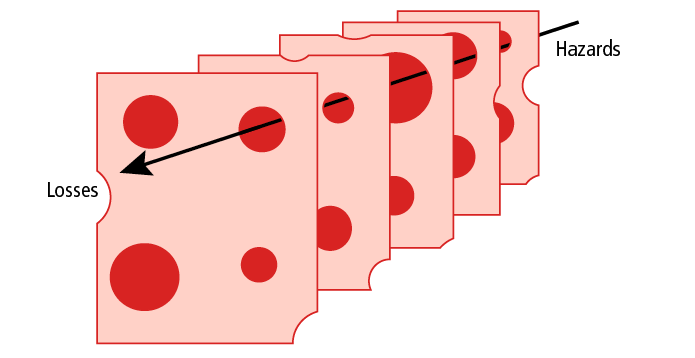

Reason (2000) described the "Swiss Cheese" model, where hazards (human error) are like holes in a block of Swiss cheese. They occur at different levels and penetrate to varying depths. In this model, "losses" (harm or serious harm occurring to a child) only occur when a number of hazards (risk factors or human error) align and form a hole through the entire block of cheese. If systems are in place to ensure that the hazards never penetrate more than a few layers, then the integrity of the system is maintained, and children are protected (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Reason's "Swiss Cheese" model

Adapted from Reason (2000).

Both Reason (2000) and Munro (2009) noted that while it is not possible to eliminate human error or ensure child safety, the consequences of errors can be minimised by establishing systems that recognise that error will occur and things will go wrong.

The Munro report also noted the importance of feedback loops, whereby it is acknowledged from the outset that errors will occur but rather than move to a punitive approach (or a personal approach as Reason (2000) described in his model), the errors are acknowledged, learned from, and that information is fed back into the model. The model is adapted every time an error occurs to minimise both the likelihood of it reoccurring and the consequences of that error.

A practical application of the Swiss Cheese model could be employed as part of the collaborative development of a safety plan for the family. Using the systems approach would enable the caseworker to put a series of safeguards in place to provide for the child's safety and wellbeing would be maintained, despite predictable human error.

Practical strategies for working with families

A recent project conducted between the Australian Centre for Child Protection and The Benevolent Society examined what the critical practice components were in home-based intensive family support programs that had been found to be effective for working with families in which parenting was at times unsafe (Iannos, Bromfield, & Antcliff, 2012). Central to practice with families in these circumstances was the ability to engage families and, in partnership with families, to develop a plan to ensure safety for children in the home. In order to be effective, programs need to assist parents to address underlying causal factors such as mental illness or addictions. In addition, the project highlighted the importance of interventions, which supported parents to learn to better regulate their emotions and to learn new skills.

Working with the family through the use of motivational interviewing techniques sets the context and increases understanding of the context of parental motivation to change and provide the safe environment for their children. For a description of these techniques, see The Application of Motivational Interviewing Techniques for Engaging "Resistant" Families (Iannos & Antcliff (2013a).

Initially, families have to be engaged and trust the caseworker, which can be challenging, especially if previous experience with child authorities has been negative. Australian research has shown that many parents are afraid to nominate their need for support services because of a fear that they may be deemed to have failed in their parenting (Tucci, Mitchell, & Goddard, 2005). Motivational interviewing techniques have been demonstrated to assist caseworkers in less confrontational and more sympathetic communication style through the use of empathetic and reflective listening styles, thereby minimising resistance from families. Once a trusting relationship is established the use of the REDS and OARS principles (described in Box 1) can be used to deal with ambivalence and move parents toward necessary change talk (Iannos & Antcliff, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c).

Box 1: REDS and OARS principles

REDS - to work with ambivalent parents

- Roll with resistance - avoid confrontation, connect with parents to move in the same direction.

- Express empathy - make a genuine effort to understand parents' perspective.

- Develop discrepancy - identify ambivalence through discrepancies between core beliefs, values and behaviours.

- Support self-efficacy - support hopefulness by identifying and affirming personal strengths and previous successes.

OARS - to elicit change talk

- Open-ended questions - encourage answers from parents' perspective as opposed to closed questions with yes/no responses that don't allow parents any room to move.

- Affirm - listen for parent's strengths and values and reflect back in affirming manner.

- Reflective listening - use of reflective statements as opposed to questions.

- Summarise - summarise to organise the session and clarify discussion.

For more information see: The Application of Motivational Interviewing Techniques for Engaging "Resistant" Families (Iannos & Antcliff, 2013a).

Source: Morrison (2010)

Once a family is engaged and ready to make changes, it is possible to establish a safety plan. The priority is to provide a safe environment for the child and do so while the child remains with the family. Both the safety plan development tool described by Iannos and Antcliff (2013c) and the systems approach described by Munro (2010) and Reason (2000) advocate for a non-judgemental approach to the family to identify the strengths and child-focused concerns of the family. From the outset, it is important to acknowledge that errors will occur (holes in the cheese) and what needs to be done to provide for the safety of the child despite those errors. For example, a caseworker works with the child and substance-abusing parent to develop a safety plan (system) that provides for the wellbeing and safety of the child if the parent should relapse - often this occurs in the form of an intensive family support program.

Part of the safety plan might include "safety nets" or "systems" designed to support the family, which can be located at different levels of the ecological model. The support for the child or family may come from other family members, neighbours, teachers and other members of the school environment and societal support through health or formal child care systems - like layers of cheese stopping the hazard from penetrating from one side of the block through the entire block of cheese. For example, the caseworker would design the safety plan knowing that one of the family "strengths" is that a grandparent lives in the next block, so when the parent is unable to care for the child, the child knows to contact the grandparent for assistance. Acknowledging that this will happen from the outset allows the grandparent to provide for the child and let the caseworker know what's happening so that the caseworker can put services in place to support the parent and get them back on track.

Applying Reason's Swiss Cheese Model to safety planning

Reason's Swiss Cheese Model can be applied to the four questions posed by the Signs of Safety® framework (Turnell, 2012):

- What are we worried about? What are the "holes" in the cheese?

- What's working well? What are the various layers of protection currently in place?

- What needs to happen? Can the "hole" be filled or narrowed?

- How safe is the family? Are all the "holes" lining up?

For more information on Signs of Safety® framework, see Planning for Safety With At-Risk Families: Resource Guide for Workers in Intensive Home-Based Family Support Programs (Iannos & Antcliff, 2013c).

As noted by Munro (2010), the feedback loop is important in this process. After the child is no longer at immediate risk, the parent, child and caseworker must reconsider the safety plan and evaluate the plan. This is done in a non-judgemental manner but with the aim of having the parent change the behaviour or issue that led to relapse (as in the example above) and minimise the risk of future "holes" opening in the cheese.

It is important to note that a core component of the system approach is trust. A culture must be designed in which the reporting of "expected errors" doesn't result in punitive actions, but rather support and system engagement to protect the child and then modification of the systems to minimise the likelihood of re-occurrence. For this model to work the parent must trust the caseworker to provide support, the child must trust that the parent and caseworker will provide for their safety, and the caseworker must trust that the parent will work with them to provide a safe environment for the child.

An example of a system approach used to support vulnerable, high-risk families is an intensive home based support program. Iannos and Antcliff (2013c) describe a practical approach to developing and implementing a safety plan for these families using evidence based practice, see Planning for Safety with At-Risk Families: Resource Guide for Workers in Intensive Home-Based Family Support Programs.

Discussion

Child protection is complicated and there is no way to "ensure" or "guarantee" the safety of a child all of the time. Use of a public health model of child protection relies on the early identification of risk factors for child protection and putting in processes to minimise that risk. The ecological model of child protection demonstrates how the child's environment can be used to minimise risk and capitalise on strengths. Previous research has shown that safe communities and families for children are facilitated by community involvement, are locally relevant, have accessible programs and integrated program design, identify and address risk factors, and include children's views (Nair, 2012).2 If the strengths in the environment are applied and risks minimised via a systems approach, it may be possible to provide safe environments for children who live in families where occasionally the environment doesn't meet a standard of "good enough" parenting.

Where children remain with their families but parents cannot consistently maintain a safe environment for their children, intensive home-based support should aim to reduce re-notification or re-substantiation and to prevent the removal of children into care. These programs are not short term, are resource intensive (require frequent input from caseworkers) (Iannos & Antcliff, 2013b) and will benefit from a systems approach. Ideally, the approach should include contributions from "all local services, including health, education, police, probation and justice with the experiences of children, young people and families at heart" (Munro, 2011, p. 7). A multi-system approach should be better at monitoring, learning and adapting, thereby improving outcomes for children.

Further CFCA reading

Australian legal definitions: When is a child in need of protection

History of child protection services

Issues for the safety and wellbeing of children in families with multiple and complex problems: The co-occurrence of domestic violence, parental substance misuse, and mental health problems (NCPC Issues Paper No. 33).

Safe and supportive families and communities for children: A synopsis and critique of Australian research (CFCA Paper No. 1)

2 For more information see: Safe and Supportive Families and Communities for Children: A Synopsis and Critique of Australian Research

References

- Bromfield, L., Lamont, A., Parker, R., & Horsfall, B. (2010). Issues for the safety and wellbeing of children in families with multiple and complex problems: The co-occurrence of domestic violence, parental substance misuse, and mental health problems (NCPC Issues Paper No. 33). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues33/>

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513-531.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). The ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723-742.

- Budd, K. (2001). Assessing parenting competence in child protection cases: A clinical practice model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4(1), 1-18.

- Council of Australian Governments. (2009). Protecting children is everyone's business: National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Darlington, Y., Healy, K., & Feeney, J. (2010). Approaches to assessment and intervention across four types of child and family welfare services. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(3), 356-364.

- Davies, C., & Ward, H. (2012). Safeguarding children across services: Messages from research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Fallon, B., Trocme, N., & Maclaurin, B. (2011). Should child protection services respond differently to maltreatment, risk of maltreatment and risk of harm? Child Abuse and Neglect, 35(4), 236-239.

- Gilbert, R., Widom, C., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373(9657), 68-81.

- Higgins, D., & McCabe, M. (2000). Multi-type maltreatment and the long-term adjustment of adults. Child Abuse Review, 9(1), 6-18.

- Hilferty, F., Mullan, K., van Gool, K., Chan, S., Eastman, C., Reeve, R. et al. (2010). The evaluation of Brighter Futures, NSW Community Services' early intervention program. Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, University of NSW.

- Hunter, C. (2012). Is resilience still a useful concept when working with children and young people? (CFCA Paper No. 2). Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Iannos, M., & Antcliff, G. (2013a). The application of motivational interviewing techniques for engaging "resistant" families. Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Iannos, M., & Antcliff, G. (2013b). Parent-skills training in intensive home-based family support programs. Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Iannos, M., & Antcliff, G. (2013c). Planning for safety with at-risk families: Resource guide for workers in intensive home-based family support programs. Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Iannos, M., Bromfield, L., & Antcliff, G. (2012, August). "What works in Child Protection?" Development of a Practice Framework for Intensive Home-Based Family Support Programs. Paper presented at the Association of Children's Welfare Agencies Conference, Sydney.

- Krug, E., Dahlberg, L., Mercy, J., Zwi, A., & Lorenzo, R. (Eds.). (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO.

- Lamont, A., & Bromfield, L. (2009). Parental intellectual disability and child protection: Key issues (NCPC Issues No. 31). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/sheets/rs22/index.html>

- Lamont, A., & Bromfield, L. (2010). History of child protection services (NCPC Resource Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Munro, E. (2009). Managing societal and institutional risk in child protection. Risk Analysis, 29(7), 1015-1023.

- Munro, E. (2010). The Munro Review of Child Protection. Part 1: A systems analysis. Retrieved from <www.education.gov.uk/publications/standard/publicationDetail/Page1/DFE-00548-2010>.

- Munro, E. (2011). The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final report. A child-centred system. London: Department for Education. Retrieved from <https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/standard/publicationDetail/Page1/CM%208062>.

- Nair, L. (2012). Safe and supportive families and communities for children: A synopsis and critique of Australian research (CFCA Paper No. 1). Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Price-Robertson, R., & Bromfield, L. (2011). Risk assessment in child protection (NCPC Resource Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Price-Robertson, R., Smart, D., & Bromfield, L. (2010). Family is for life: Connections between childhood family experiences and wellbeing in early adulthood. Family Matters, 85, 7-17.

- Reason, J. (2000). Human error: Models of management. Western Journal of Medicine, 172(June), 393-396.

- Tucci, J., Mitchell, J., & Goddard, C. (2005). The changing face of parenting. Exploring the attitudes of parents in contemporary Australia. Ringwood, Vic.: Australian Childhood Foundation.

- Tully, L. (2008). Family preservation services: Literature review. Sydney: Centre for Parenting and Research Service System Development and NSW Department of Community Services.

- Turnell, A. (2012). Signs of Safety: Briefing paper (2nd ed.). Perth: Resolutions Consultancy. Retrieved from <www.signsofsafety.net>

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Geneva: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Weeks, W., & Quinn, M. (Eds.). (2000). Issues facing Australian families: Human services respond (Third Edition ed.). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia.

Debbie Scott is a Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The author wishes to acknowledge the valuable contribution of Leah Bromfield (Australian Centre for Child Protection, University of South Australia). Appreciation is also extended to Elly Robinson and Rhys Price-Robertson of the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-922038-24-1