Ageing parent carers of people with a disability

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Download Research report

Overview

This report presents information on parents who care for people with a disability in Victoria, focusing on the issue of ageing.

The ageing of the Australian population is expected to increase the proportion of the population requiring care as a result of a disability or frail old age. This is expected to increase the demand for informal care (see, for example, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2004; Percival & Kelly, 2004). Informal care is the unpaid support and assistance provided to people with a disability or chronic illness by their families and friends. Informal care is critical to the welfare system as it provides the main source of assistance for people with a disability or chronic illness and of home-based support over a sustained period of time. The value of services provided by informal carers in Australia exceeded $40 billion in 2010 (Access Economics, 2010). Informal carers commonly help with a range of tasks, including self-care, health care, mobility and property maintenance. They play a significant role in supervising and encouraging people who need assistance with day-to-day activities, supporting their social inclusion, managing formal care services and advocating on their behalf. There are an estimated 771,400 primary carers in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2010), and they are usually close family members living with the person for whom they care. They provide the most support and assistance to people with a severe or profound core activity limitation.

Within general concerns about an increasingly ageing population, an issue that has received much less attention is that the number of older parent carers of a son or daughter with a disability will also increase in coming decades (Llewellyn, Gething, Kendig, & Cant, 2003). Indeed, the estimated number of ageing parent primary carers (aged 65 years and over) in Australia increased from 6,400 in 2003 to 16,800 in 2009 (ABS, 2004, 2010). Consistent with this trend, the reports on disability support service users show that the number of service users who were cared for by their parents rose from 76,873 in 2008-09 to 84,032 in 2009-10, and the number of users cared for by parents aged 65 years or over increased from 7,343 to 8,111 during the same period (AIHW, 2011a, 2011b).

As parent carers get older, their anxiety increases about who will care for their adult child with a disability when they are no longer able to do so or should they predecease their adult child. The uncertain future that parent carers face was highlighted in a study by Llewellyn et al. (2003) about the lifetime caring experiences of ageing parents who look after a son or daughter with intellectual disability:

Becoming older after an adult lifetime of caring brings physical and emotional tiredness and concern for the future. Faced with the non-normative expectation that, as older parents, they will most likely die before their cared-for adult son or daughter heightens the anxiety already felt about the likelihood of deteriorating health and being unable to continue primary carer responsibilities … For older parent carers the question is who will look after my child and in the way that I have done? (pp. 41, 44)

Many people with a disability are equally concerned about what will happen to them and who will support them when their parents die. The Disability and Ageing Inquiry by the Senate Community Affairs References Committee (2011) sought to identify ways in which to support families to develop lifelong and sustainable care plans for the future. Its report provided evidence that a relatively low proportion of ageing parents plan for the future for their son or daughter with a disability. Issues that need to be considered include the difficulties experienced by an adult with a disability with transitioning to care outside the family home if there are no alternative accommodation places available. The lack of accommodation choices in turn affects a family's ability to put in place plans for the future.

If a parent carer is no longer able to care for their son or daughter with a disability, the person with a disability may then require access to housing and support services, as well as ongoing psychosocial support from other family members and friends. Informal unpaid family care may be an outcome for some families. For parent carers, planning ahead is important; however, the Disability and Ageing Inquiry (Senate Community Affairs References Committee, 2011) found that it is difficult for many ageing parents to plan for the future. Various barriers hinder them from doing so. For example, they may have difficulty accessing information; there may be a lack of time, energy and resources; or there may be issues relating to accessing needed services. The inquiry report stressed that many ageing parent carers find planning for the future a difficult and multifaceted task. Existing programs in Australia for planning for the future are not usually linked to funding, which would otherwise enable families to plan and implement secure housing arrangements for the person with a disability. People with a disability face enormous difficulties with leaving the parental home and finding alternative accommodation, which leads many to remain in the parental home well into middle age.

The inquiry report (Senate Community Affairs References Committee, 2011) emphasised the need for a number of interconnected and coordinated services for ageing parents and their son or daughter. These include the need to improve the availability, accessibility and quality of information for such families; provide support for psychosocial, legal and financial planning; and make available more options for housing and support. These services would provide more certainty and confidence for parent carers who are planning for the future and for their son or daughter with a disability.

With improvements in health care services and community support, people with a disability are likely to live longer, and are more likely than in the past to outlive their parents (Patja, Livanainen, Vesala, Oksanene, & Ruoppila, 2000; Strauss, Shavelle, Reynolds, Rosenbloom, & Day, 2007). Population growth and ageing have implications for whether the current highly rationed system of housing and support will be able to cope with the potential increase in the demand for services from this group (Pierce, 2007; Pierce & Paul, 2010). Beer and Faulkner (2009) carried out a qualitative study on housing issues among people with a disability and their carers, and found a great deal of family concern about where persons with a disability would live if they lost their carers.

This paper, commissioned by Carers Victoria, uses existing data to explore the numbers, characteristics and potential growth over the coming decades of the population of ageing parents looking after a son or daughter with a disability, in Victoria as well as in Australia.

2.1 Defining disability and datasets for analyses

There is no nationally accepted definition of "disability" or method of categorising the severity of different types of disabilities in Australia. According to the ABS (2010), "disability" is defined as follows:

A person has a disability if they report that they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities. (p. 27)

Estimates of the number of people with a disability vary markedly, depending on data sources and survey designs (Productivity Commission, 2010). The Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) is considered to be the best Australian source of information on the number of people with a disability. This nationally representative survey was carried out by the ABS in 1998, 2003 and 2009, and there were similar surveys in earlier years. SDAC 2009 had a sample of over 64,000 persons (with and without a disability), from both private and non-private dwellings, and it is a key dataset for estimating prevalence information on disability and carers. This survey collected detailed information from three population groups: people with a disability; older people (aged 60 years and over); and carers, the people who provide support and assistance to people with a disability and older people.

People with a disability vary in their need for assistance. In each SDAC, when people were affected by their disability in the core activities of communication, mobility and self-care, they were categorised into four levels of disability (profound, severe, moderate and mild) according to whether a person needed help with, had difficulty with or used an aid or equipment for specific tasks related to the core activities. A person with a profound disability was one who was unable to do a core activity task, or always needed help or supervision with it. A person with a severe disability sometimes needed help or supervision with a core activity task, or had difficulty understanding or being understood by family and friends, or could communicate more easily using sign language or other non-spoken form of communication. Although people with a moderate disability may not have needed any assistance, they had difficulty with at least one core activity task. People with a mild level of disability could perform core activity tasks without any help or difficulty; nevertheless, they may have needed aids and equipment, or needed help or supervision when using public transport or with other life tasks.

In addition to these four SDAC levels, the ABS (2010) also describes another group of people with a disability. This group may not need any assistance in their core activities; however, their condition may mean they have difficulties participating in education or employment, and therefore may need assistance with self-management and planning.

The concept of "parent carers" is also not entirely straightforward. Parents who look after their son or daughter with a disability may not identify themselves as being "carers". Indeed, parents living with their son or daughter with a moderate or mild disability or with a disability restricting participation in education or employment are not generally considered to be "primary carers" in statistical collections,1 although most provide informal care and support to their son or daughter and assist them with everyday activities, financial support, decision-making, self-management and planning. Llewellyn et al. (2003) noted that parent carers often see themselves primarily as a parent who takes responsibility for the welfare of their son or daughter with a disability, rather than as a carer.

In this paper, we focus on parents who live in the same residence as their son or daughter who has a disability that leads to a core activity limitation or results in an education or employment restriction. These parents are referred to as "parent carers", and parents who are 65 years and over are considered "ageing parent carers". There are also parents who have a child with a disability who is living elsewhere, but while many of these parents provide ongoing assistance to their sons or daughters, they are not considered in this paper. SDAC 2009 estimated that there were 4,100 primary carers aged over 65 who looked after a son or daughter living elsewhere. It is likely that many of these shared the concerns of co-resident parent carers about a future when they can no longer support and assist their adult child.

This paper uses SDAC 2009 and 2006 Census data to examine the characteristics of parents and their son or daughter with a disability who lives with them. In the analyses using SDAC, people with a disability who were living with their parents have been divided into two groups according to their disability status: (a) those with profound or severe core activity limitations ("more severe disability"); and (b) those with moderate or mild core activity limitations, or with an education or employment restriction ("milder disability").

Because the growing number of parent carers, especially ageing parent carers, has implications for service demand, this paper also uses the prevalence rate of people with a disability who live with their parents - derived from SDAC 2009 and population projections released by the ABS (2008) - in order to explore future scenarios and the likely growth in the number of ageing parent carers in the coming decades.

2.2 Limitations of existing data

The existing data sources that help understand the needs of people with a disability and their carers, while important, also have their limitations.

SDAC datasets, for example, are valuable sources of information for understanding the needs of people with a disability, their families and those who provide care, but it is difficult to use the surveys to examine issues such as the socio-economic characteristics of ageing parent carers in certain subgroups (e.g., those in their 70s and beyond), due to insufficient sample sizes.

While the 2006 Census data can be used to fill some of the gaps resulting from the sample size limitations of the SDAC, the Census itself also has its limitations. The 2006 Census included just one question that identified people with a profound or severe disability. The identification of people with a profound or severe disability based on a single question is not as rigorous as other surveys such as SDAC. Thus, it is likely to have underestimated the number of people with a profound or severe disability (Productivity Commission, 2010). It was also not possible to use the Census to identify older parents who looked after their adult children with a milder disability.

Another example is the Disability Services National Minimum Data Set (NMDS), which collects data about services users under the National Disability Agreement (NDA). This includes data about informal care, including primary carers who provide sustained assistance to a family member, friend or neighbour. This dataset contains limited information, as NDA employment services are not required to collect information about informal carers or about living arrangements. In addition, the NMDS only captures service users, not those who have support needs but do not use or have withdrawn from these services.

1 The ABS (2010) defines a "primary carer" as follows: "A primary carer is a person who provides the most informal assistance, in terms of help or supervision, to a person with one or more disabilities or aged 60 years and over. The assistance has to be ongoing, or likely to be ongoing, for at least six months and be provided for one or more of the core activities (communication, mobility and self-care)" (p. 34).

This section provides an overview of the demographic characteristics of people with a disability who are living with their parents, according to their disability status. The analyses are based on the data from SDAC 2009.

3.1 Characteristics of people with a disability living with their parents

In 2009, there were about 446,300 Australians with a disability (profound, severe, moderate or mild core activity limitation, or with education/employment restrictions) who were living with their parents. Of these, 218,700 were adult children (15 years and over) and 236,100 had a more severe disability. There were 626,000 fathers and mothers who lived with a son or daughter with a disability, and 60,000 of these parents were aged 65 years and over.

Table 1 shows the age distribution of people with a disability who were living with their parents, by their disability status. More than half of these people (56%) were under 15 years of age, close to a quarter (24%) were 15-24 years, nearly a tenth (9%) were 25-34 years, and an eighth (12%) were aged 35 years and over. However, those with a more severe disability had different age profiles from those with a milder disability, with the former group being younger than the latter. For example, 68% of those with a more severe disability were under 15 years, compared with 43% of their counterparts with a milder disability. In contrast, in the more severe disability group, 24% were aged 15-34 years and 9% were older than 35 years. The proportions of these age groups for those with a milder disability were 42% and 15% respectively.

It is worth noting that among people with a disability aged 35 years and over, around nine in ten (86% of those with a more severe disability and 90% with a milder disability) had at least one parent aged 65 years or older. Among those with a disability aged 45 years and over, all had parents aged 65 years or older. And while the majority of people with a disability who were living with their parents were with both parents (62%), a substantial proportion lived with a parent who was single (38%), often their mother.

| Age | More severe disability a (%) | Milder disability b (%) | All (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 15 years | 67.8 | 42.6 | 56.1 |

| 15-24 years | 17.0 | 31.4 | 23.7 |

| 25-34 years | 6.7 | 10.8 | 8.6 |

| 35-44 years | 5.0 | 6.6 | 5.7 |

| 45-54 years | 2.4 | 5.6 | 3.9 |

| 55-64 years | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| 65+ years | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of observations | 707 | 611 | 1,318 |

Notes: a People with profound or severe core activity limitations. b People with moderate or mild core activity limitations, or with an education or employment restriction. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: SDAC 2009

Among people with a disability living with their parents, the most common problem caused by their main condition was having difficulty in learning or understanding things, with more than half having this difficulty. One-quarter had a speech difficulty, the second most common problem. Such cognitive problems were more common among those with a more severe disability than they were for those with a milder disability (see Appendix Table A1).

3.2 Age of parent carers

Table 2 shows that most parent carers were aged 35-54 years, with 69% of fathers and 62% of mothers being in this age group. Fourteen per cent of fathers and 10% of mothers were 55-64 years, while 8% of fathers and 10% of mothers were 65 years and over. Corresponding to the different age profiles of people with either a more severe or a milder disability (discussed in section 3.1 above), parent carers with a son or daughter with a more severe disability were younger than those with a child with a milder disability. Fifty-one per cent of fathers and 60% of mothers who looked after a son or daughter with a more severe disability were under 45 years, compared with 34% of fathers and 43% of mothers of offspring with a milder disability. By contrast, 27% of fathers and 26% of mothers of a child with a milder disability were aged 55 years or older, compared to 18% of fathers and 16% of mothers with a child with a more severe disability.

| Age of parent | Fathers | Mothers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child with more severe disability a (%) | Child with milder disability b (%) | All (%) | Child with more severe disability a (%) | Child with milder disability b (%) | All (%) | |

| 15-24 years | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| 25-34 years | 13.3 | 4.7 | 9.4 | 19.5 | 10.9 | 15.7 |

| 35-44 years | 37.7 | 29.7 | 34.1 | 39.1 | 31.8 | 35.9 |

| 45-54 years | 30.8 | 39.0 | 34.5 | 23.4 | 30.5 | 26.5 |

| 55-64 years | 12.6 | 15.4 | 13.8 | 8.1 | 13.4 | 10.4 |

| 65-74 years | 3.1 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 5.6 |

| 75+ years | 2.4 | 5.5 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 6.9 | 4.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of observations | 422 | 344 | 766 | 616 | 478 | 1,094 |

Notes: a People with profound or severe core activity limitations. b People with moderate or mild core activity limitations, or with an education or employment restriction. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: SDAC 2009

Of course, the older a son or daughter with a disability is, the greater the age of their parent carers; for example, at least 80% of parent carers with adult children with a disability aged 35 years and over were themselves 65 years and older.

3.3 Employment status of parent carers

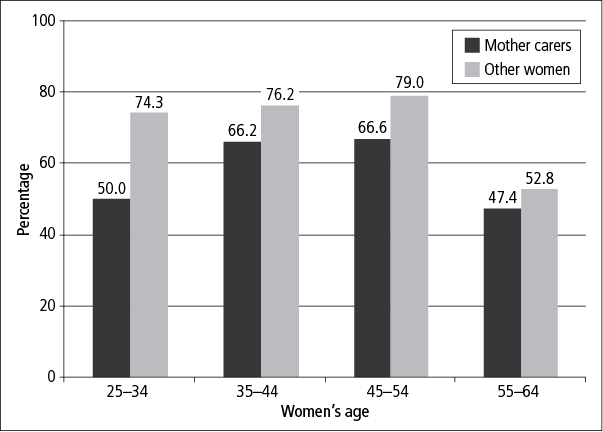

There is evidence that an individual's employment history affects income in later life, and lower retirement income was linked with fewer years of employment history (de Vaus, Gray, Qu, & Stanton, 2011; Sefton, Evandrou, & Falkingham, 2011). While over the last few decades an increasing number of women (including those with children) have entered paid employment, women still take the main responsibility for caring for their children (Craig, Mullan, & Blaxland, 2010). Therefore, the effects on labour force participation of having a child with a disability are more likely to be felt by mothers than by fathers. Figure 1 shows that mother carers across all age groups were less likely to be employed (full-time or part-time) compared with other women.

Figure 1: Female employment rates, by age and mother carer status, 2009

Source: SDAC 2009

3.4 Parent carers with a disability

It is important to note that some parent carers have a disability themselves and therefore may also need help to sustain the care of their son or daughter at home. Of parents who were living with a son or daughter with a disability, 6% of fathers and 10% of mothers had a profound or severe disability themselves (and thus needed assistance with at least one core activity), and 19% of fathers and 21% of mothers had a milder disability. Understandably, disability conditions were more prevalent among older parent carers; for example, 33% of mother carers aged 65 years and older had a more severe disability and 34% had a milder disability, compared with 7% and 17% respectively of mothers aged under 55 years.

3.5 Summary

Of the people with a disability who were living with their parents, four in ten were adults (aged 15 years and older), and more than one in ten were aged 35 years and older. People with a milder disability who were living with their parents were older on average than those with a more severe disability. A substantial minority of parent carers were in old age (65 years and older), and a large proportion were approaching old age (55-64 years). Mother carers, in particular, were less likely to be employed and therefore more financially disadvantaged when compared with other women of the same age. It is worth noting that some parent carers may also need help themselves, with ageing parents being more likely to have such needs.

As shown above, a substantial minority of parent carers were aged 65 years and older. It is important to have a better understanding of these ageing parents and their needs. The limited sample size of the SDAC 20092 meant it was not possible to further examine the demographic characteristics of older parent carers by smaller age groups. The 2006 Census data enable such analyses. However, as mentioned in section 2.2, the 2006 Census data are likely to underestimate the number of people with a more severe disability and thus underestimate the number of their parent carers. Despite this shortcoming, the 2006 Census is useful because it is a count of the whole Australian population and allows a breakdown of the data by individual states and territories. This section examines the characteristics of parents aged 65 years and older who were living with adult children with a more severe disability. It explores family type, whether the parent carer was in paid work, whether the parent was living with a partner, family income, and whether the parent needed assistance themselves in their core activities. The analyses compare Victorian and national data. The data is reported separately for Victoria because the research was commissioned by Carers Victoria, who are particularly interested in the Victorian situation.

4.1 Characteristics of ageing parent carers

As shown in Table 3, there were nearly 5,000 parents aged 65 years and older in Victoria who were living with a son or daughter with a more severe disability. The number was about 18,000 nationally, according to the 2006 Census data. It is worth noting that there were 2,943 fathers and 3,152 mothers in Victoria aged 55-64 years, and 10,858 fathers and 11,582 mothers in Australia aged 55-64 years who are approaching older age (data not shown in the table).

| Age | Victoria | Australia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | Mothers | Total | Fathers | Mothers | Total | |

| 65-69 years | 844 | 960 | 1,804 | 3,031 | 3,322 | 6,353 |

| 70-74 years | 570 | 709 | 1,279 | 2,076 | 2,578 | 4,654 |

| 75-79 years | 412 | 489 | 901 | 1,417 | 1,962 | 3,379 |

| 80-84 years | 215 | 347 | 562 | 801 | 1,339 | 2,140 |

| 85+ years | 102 | 214 | 316 | 430 | 907 | 1,337 |

| Total | 2,143 | 2,719 | 4,862 | 7,755 | 10,108 | 17,863 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations.

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

Many ageing parent carers are not living with a partner (i.e., are sole parents) and thus have to shoulder the bulk of the caring responsibilities for the adult with a disability. Table 4 shows that this was especially the case for mother carers, with 54% of mother carers (compared with 14% of father carers) aged 65 years and older in Victoria being sole parents in 2006. A similar picture emerged nationally. The older both mother and father carers were, the more likely they were to be living without a partner, in both Victoria and Australia as a whole. For example, 37% of mother carers aged 65-69 years in Victoria were without a partner, and this proportion rose to 48% for those aged 70-74 years and to 78% for those aged 80-84 years.

| Age | Victoria | Australia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers (%) | Mothers (%) | Fathers (%) | Mothers (%) | |

| 65-69 years | 7.8 | 37.2 | 9.3 | 39.6 |

| 70-74 years | 11.8 | 48.4 | 12.8 | 50.3 |

| 75-79 years | 13.8 | 61.1 | 16.5 | 62.9 |

| 80-84 years | 25.6 | 77.6 | 27.8 | 78.1 |

| 85+ years | 52.5 | 87.4 | 45.5 | 87.9 |

| Total (65+ years) | 13.9 | 53.6 | 15.4 | 56.3 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations.

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

4.2 Housing tenure, income and employment of ageing parent carers

Housing tenure has a significant effect on the financial security of families in which parents are caring for an adult child with a disability, especially those with ageing parent carers.

Table 5 shows the housing tenure status in 2006 of parent carers aged 65 years and older in Victoria by age and gender, while Table 6 depicts the weekly family income of these parents. (Given that the trends between Victoria and the nation as a whole were similar, the tables on housing tenure and family income for Australia are presented in the Appendix in Tables A2 and A3).

| Age | Fully owned (%) | Purchasing (%) | Public housing (%) | Private rental (%) | Other housing (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | ||||||

| 65-69 years | 77.3 | 14.2 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 82.3 | 9.3 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 88.0 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 84.6 | 6.0 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 87.1 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 81.9 | 10.0 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 0.9 | 100.0 |

| Mothers | ||||||

| 65-69 years | 75.9 | 11.7 | 4.7 | 6.9 | 0.9 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 78.3 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 0.9 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 84.2 | 6.1 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 78.7 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 69.7 | 9.0 | 7.5 | 11.9 | 2.0 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 77.9 | 9.2 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 1.0 | 100.0 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations. Excludes those whose housing tenure was not stated (3% of fathers and 4% of mothers). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding. See Appendix Table A2 for data relating to Australia as a whole.

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

The majority of ageing parent carers in Victoria owned their home outright in 2006 (82% of fathers and 78% of mothers); a substantial minority were paying a mortgage for their own homes (10% of father carers and 9% of mothers); and small proportions were either in public housing (3% of fathers and 6% mothers) or in private rental (5% of fathers and 6% of mothers). Beer and Faulkner (2009) found that people with a disability under 65 years of age, and their families, were more likely than other home purchasers to experience mortgage stress because they tend to have a low income. The authors also noted that people with a disability who are in the rental market spend a higher proportion of their income (commonly income support payments) on housing than other renters. Despite wanting to own their own home, many find it harder to enter the housing market than others. While Beer and Faulkner focused on people under 65 years, we would expect that a proportion of parent carers aged 65 years and over who are paying a mortgage or private rental accommodation would also experience mortgage stress or difficulty in meeting housing costs. The high rates of home ownership of currently older carers (Table 5) reflect the fact that they purchased their home when housing was generally more affordable. Since the 1970s, housing affordability and home ownership rates have gradually declined (Yates, 2007), making it harder for younger parent carers to own their own home, which may, in turn, cause difficulties in meeting housing costs in the future.

Table 6 shows that one in ten father carers and nearly two in ten mother carers had weekly family incomes of less than $500 in 2006. It is not surprising that mother carers had less family income than father carers, given that they were more likely than fathers to be single (unpartnered). It is also evident in Table 6 that the older the parent carer, the lower their family income. For example, 15% of mother carers aged 65-59 years were on family incomes of less than $500 per week, while the proportion was 23% for mother carers aged 85 years and older.

| Age | < $500 (%) | $500-999 (%) | $1,000-1,699 (%) | $1,700+ (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | |||||

| 65-69 years | 9.2 | 45.9 | 30.0 | 14.9 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 10.7 | 54.5 | 23.4 | 11.4 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 10.8 | 61.2 | 20.8 | 7.1 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 8.7 | 56.4 | 25.6 | 9.2 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 25.0 | 48.9 | 22.7 | 3.4 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 10.6 | 52.4 | 25.7 | 11.4 | 100.0 |

| Mothers | |||||

| 65-69 years | 15.4 | 52.2 | 23.7 | 8.7 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 18.0 | 56.3 | 19.1 | 6.6 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 21.6 | 54.7 | 19.4 | 4.2 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 19.6 | 60.9 | 14.1 | 5.4 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 23.0 | 59.4 | 15.5 | 2.1 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 18.4 | 55.4 | 19.9 | 6.4 | 100.0 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations. Excludes those whose family income was not stated (10% of fathers and 10% of mothers). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding. See Appendix Table A3 for data relating to Australia as a whole.

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

The majority of people aged 65 years and over are retired and only a small proportion are in paid work. Nevertheless, over the last decade, an increasing proportion of people over 65 years have remained in employment (Hayes, Qu, & Weston, 2011). Table 7 shows that 15% of father carers and 6% of mother carers aged 65 years and over were employed in Victoria in 2006 (similar proportions were also evident for Australia). However, the proportions of parent carers in Victoria who were in paid work declined sharply with increasing age, from 27% of father carers aged 65-69 years, to less than 10% in older age groups, and from 10% of mother carers aged 65-69 years, to less than 5% in older age groups.

| Age | Victoria | Australia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers (%) | Mothers (%) | Fathers (%) | Mothers (%) | |

| 65-69 years | 26.8 | 9.6 | 24.7 | 9.6 |

| 70-74 years | 9.0 | 5.3 | 9.7 | 4.9 |

| 75-79 years | 6.3 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 2.4 |

| 80-84 years | 5.1 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.4 |

| 85+ years | 3.2 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 4.2 |

| Total (65+ years) | 14.9 | 5.8 | 14.2 | 5.5 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations. Excludes those whose family income was not stated (4% of fathers and 5% of mothers in Victoria; 4% of fathers and mothers in Australia).

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

4.3 Ageing parent carers with a disability

Some ageing parents who are living with adult children with a more severe disability may actually need assistance with core activities themselves.3 Table 8 shows that 23% of ageing father carers and 31% of ageing mother carers in Victoria needed assistance themselves with core activities. These were similar to the proportions nationally. Understandably, the proportions with such needs increased with age, from 15% of father carers and 16% of mother carers aged 65-69 years in Victoria, to 68% and 71% respectively of those aged at least 85 years. In some instances, ageing parent carers may both receive assistance from their adult children with a disability and provide care to those adult children. In other circumstances, parents are obliged to continue providing support and assistance when the priority need may be for housing and support for their offspring.

| Age | Victoria | Australia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers (%) | Mothers (%) | Fathers (%) | Mothers (%) | |

| 65-69 years | 15.1 | 16.0 | 13.6 | 14.5 |

| 70-74 years | 18.5 | 23.0 | 17.6 | 22.1 |

| 75-79 years | 29.0 | 40.1 | 25.7 | 37.1 |

| 80-84 years | 36.6 | 51.3 | 38.5 | 51.3 |

| 85+ years | 68.1 | 70.5 | 57.2 | 68.2 |

| Total (65+ years) | 23.2 | 31.1 | 21.8 | 30.5 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations. Excludes those whose need for assistance with core activities was not stated (4% of fathers and 5% of mothers in Victoria; 3% of fathers and 5% of mothers in Australia).

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

4.4 Summary

In summary, findings from the 2006 Census suggest that there were nearly 18,000 parent carers aged 65 years and over nationally, with nearly 5,000 in Victoria. A larger number of parent carers in Victoria (about 6,000) were approaching older age (55-64 years). More than half the mother carers aged 65 years and older were single and were likely to have sole responsibility for their adult child with a disability.

While the majority of parent carers owned their own home outright, a significant proportion were paying a mortgage or in rental accommodation. Some were likely to be experiencing housing cost distress. One in ten father carers and nearly one in five mother carers aged 65 years and older were living on family incomes of less than $500 per week and, in general, the older the parent carers, the lower their financial resources. The lower family incomes of parent carers as they age is consistent with their lower employment rates. When combined with SDAC data (2009), this suggests that caring affects parents' capacity to work and therefore their retirement incomes. Finally, between one-fifth and one-third of ageing parent carers also needed assistance with core activities themselves. Reciprocity in the care relationship is likely to exist between parents and their son or daughter with a disability.

One of the issues surrounding caring for an adult child with a disability is the ageing of their parent carers. This has implications for support service planning. This section explores the number of sons and daughters with a disability who are projected to be living with their parents in the coming decades (2010, 2020, 2030 and 2040), given the current trends and projected population. Three scenarios for both Victoria and Australia are presented, based on data from SDAC 2009 and three series of population projections by the ABS (2008): high (Series A), medium (Series B) and low projections (Series C).4 Numbers of children and adult children with a disability who would be living with their parents in the coming decades are also broken down by age (< 15 years, 15-44 years and 45+ years), which provides an indication of the growth in the numbers of ageing parent carers.

There are a several assumptions that underlie these projections. Key assumptions are that the likelihood of a person at a certain age being a child with a disability who lives with their parents (as derived from the data of SDAC 2009) remains constant in the future, and the ABS series of population projections is based on various assumptions in terms of fertility, mortality and immigration (see ABS, 2008, for details).

Table 9 shows three population growth scenarios over the next four decades (2010-40) by disability status. The number of people with a disability living with their parents in Victoria and Australia is projected to increase between 2010 and 2040. For the medium population growth scenario, the number of people with a more severe disability in Victoria will increase from 61,000 in 2010 to 76,000 in 2040, and for Australia as a whole from 249,000 to 318,000. The number of those with a milder disability is also projected to increase, from 54,000 in 2010 to 68,000 in 2040 in Victoria, and from 219,000 to 281,000 nationally.

Table 10 shows, for Victoria and Australia, the estimated growth over the next four decades in the number of people with a disability who will be living with their parents, by age group.5 For both Victoria and Australia, nearly two-thirds of those with a more severe disability and living with a parent carer will be under 15 years of age, while nearly four in ten of those with a milder disability will be under 15 years of age. The number aged 45 years of age and over with a more severe disability in Victoria is projected to be 2,200 in 2010, increasing a little to 2,900 in 2040, and the number with a milder disability is projected to increase from 4,900 to 6,700. People aged 45 years and older will of course have older parents too, and so these increases are also expected to see a rise in the number of older parents caring for an adult child into older age.

For Australia as a whole, the number of people aged 45 years and over with a more severe disability who are living with their parents is projected to increase from 8,800 in 2010 to 12,100 in 2040 and the number in this age group with a milder disability is projected to increase from 20,000 to 27,500 over this period. While these increases are smaller than the projected increases in the number of younger people with a milder disability who are living with their parents, the effect that this has on older parent carers should not be underestimated.

| Year | Victoria | Australia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More severe disabilitya | Milder disabilityb | All | More severe disabilitya | Milder disabilityb | All | |

| High population growth scenario | ||||||

| 2010 | 61,000 | 54,000 | 114,000 | 250,000 | 220,000 | 470,000 |

| 2020 | 69,000 | 60,000 | 129,000 | 291,000 | 249,000 | 539,000 |

| 2030 | 79,000 | 68,000 | 147,000 | 336,000 | 286,000 | 622,000 |

| 2040 | 86,000 | 75,000 | 161,000 | 370,000 | 321,000 | 692,000 |

| Medium population growth scenario | ||||||

| 2010 | 61,000 | 54,000 | 114,000 | 249,000 | 219,000 | 468,000 |

| 2020 | 67,000 | 58,000 | 125,000 | 275,000 | 240,000 | 515,000 |

| 2030 | 72,000 | 63,000 | 136,000 | 299,000 | 262,000 | 561,000 |

| 2040 | 76,000 | 68,000 | 144,000 | 318,000 | 281,000 | 598,000 |

| Low population growth scenario | ||||||

| 2010 | 60,000 | 54,000 | 114,000 | 248,000 | 218,000 | 466,000 |

| 2020 | 64,000 | 57,000 | 122,000 | 261,000 | 231,000 | 491,000 |

| 2030 | 66,000 | 59,000 | 125,000 | 264,000 | 238,000 | 502,000 |

| 2040 | 67,000 | 61,000 | 128,000 | 269,000 | 243,000 | 512,000 |

Notes: a People with profound or severe core activity limitations. b People with moderate or mild core activity limitations, or with an education or employment restriction. See Appendix Table A4 for confidence intervals for these data. The sum of the row cells may differ from the total due to rounding.

Source: SDAC 2009 and ABS (2008) population projections

| Year | More severe disability a | Milder disability b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 15 years | 15-44 years | 45+ years | Total | < 15 years | 15-44 years | 45+ years | Total | |

| Victoria | ||||||||

| 2010 | 38,500 | 19,800 | 2,200 | 60,500 | 19,800 | 29,000 | 4,900 | 53,700 |

| 2020 | 43,300 | 21,100 | 2,400 | 66,800 | 22,300 | 30,700 | 5,500 | 58,500 |

| 2030 | 46,500 | 23,000 | 2,600 | 72,100 | 24,100 | 33,400 | 6,000 | 63,400 |

| 2040 | 48,700 | 24,500 | 2,900 | 76,100 | 25,200 | 35,700 | 6,700 | 67,600 |

| Australia | ||||||||

| 2010 | 160,200 | 79,800 | 8,800 | 248,800 | 82,900 | 116,400 | 20,000 | 219,300 |

| 2020 | 179,700 | 85,900 | 9,900 | 275,500 | 92,800 | 124,700 | 22,400 | 239,900 |

| 2030 | 194,400 | 93,900 | 10,800 | 299,100 | 100,800 | 136,400 | 24,500 | 261,700 |

| 2040 | 205,200 | 100,600 | 12,100 | 317,900 | 106,600 | 146,500 | 27,500 | 280,600 |

Notes: a People with profound or severe core activity limitations. b People with moderate or mild core activity limitations, or with an education or employment restriction. The sum of the row cells may differ from the Total due to rounding.

Source: SDAC 2009 and ABS (2008) population projections (Series B)

4 This estimation uses what is known as a cell-based model (also referred to as a group projection or actuarial model). In this type of model, the unit of analysis is a group of people defined by a set of characteristics (in this case, age). The projection model operates by applying average probabilities of an "event happening" to the groups defined by each cell (Percival & Kelly, 2004). This type of modelling has been used quite widely in Australia; for example, Percival and Kelly used a cell-based model to project the future demand for and supply of informal carers of older persons in Australia, and the AIHW (2004) used it to project future numbers of people requiring informal care. It has also been used in other countries, such as Britain (e.g., Wittenberg, Pickard, Comas-Herera, Daies, & Darton, 1998, 2001).

5 Estimates are based on the ABS (2008) B Series (medium) population projections.

This paper examined the characteristics of people with a disability who live with their parents, the nature of their disabling conditions, and the characteristics of their parent carers (especially ageing parent carers). The number of people with a disability who will be living with their parents in the coming decades was also explored.

According to the SDAC 2009, there were 60,000 parent carers living with a son or daughter with a disability who were over the age of 65 years. While the majority of sons and daughters with a disability living with their parents were under the age of 15 years, some were well into adulthood, with 12% being 35 years and older. Those with a milder disability who were living with their parents had a significantly older age profile. A consequence of this is that those with a milder disability are more likely to have an ageing parent looking after them.

Nearly one in ten father and mother carers were aged 65 years and older, and 14% of father carers and 10% of mother carers were approaching old age (55-64 years). Some parents may have had to relinquish their caring responsibility for their son or daughter with a disability due to their own old age or other reasons, such as poor health. Indeed, one-fifth to one-third of parent carers aged 65 years and older needed assistance with core activities themselves, though it is likely that a reciprocal care relationship existed between these parents and their son or daughter with a disability.

Consistent with prior research findings that caring for a person with a disability affects participation rates in paid employment (e.g., Bittman, Hill & Thomson, 2007; Gray & Edwards, 2009), this paper showed that having caring responsibilities affected mother carers' labour force participation. It is also not surprising that parent carers, especially older parent carers, were more likely than others to have a low personal income. In particular, mother carers are disadvantaged in relation to financial provision for their own retirement.

Information on housing was also provided here because home ownership provides financial security to families. In the context of an ageing parent carer looking after their adult child with a disability, home ownership is even more important. While the majority of parent carers over 65 years of age owned their own home, a substantial minority were in other housing situations: purchasing, public housing, and private rental. Should these parents no longer be able to take care of their adult children with a disability or die, their children would not only require formal care, but also housing, and many can be expected to have limited financial means to obtain such supports.6 It is also worth noting that at least half of the mother carers aged 65 years or more were sole mothers, and other research has suggested that sole mothers are a particularly disadvantaged group (e.g., ABS, 2007; Whiteford, 2009).

This paper also explored future scenarios in terms of the number of people with a disability who will be living with a parent carer in coming decades. The projections suggest that the number will increase over time. The number of adult children with a disability who are cared for by their parents and aged 45 years and over will also rise, although the increases in this age group will be smaller. This means that there will be an accompanying increase in ageing parent carers in the future. This is consistent with the increasing number of primary parent carers reported by SDAC in 2003 and 2009.

In providing care for their adult children with a disability, older carers provide an important service to the community that saves a huge amount of public resources. Findings from this paper suggest that providing care for a son or daughter with a disability is not without cost to the carers, with some carers having lower levels of employment and financial resources, and poorer health and wellbeing. Many care for their adult son or daughter for a lifetime. It is important to recognise the contributions that these parent carers have made, and provide them with better support and services.

6 People with a disability are less likely to be in the labour force, and many rely on income support payments.

- Access Economics. (2010). The economic value of informal care in 2010. Canberra: Carers Australia.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2004). Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, 2003 (Cat. No. 4430.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). Australian social trends (Cat. No. 4102.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). Population projections, Australia 2006-2010 (Cat. No. 3222.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, 2009 (Cat. No. 4430.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2004). Carers in Australia: Assisting frail older people and people with a disability (Cat. No. AGE 41). Canberra: AIHW.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2011a). Disability support services 2008-09: Report on services provided under the Commonwealth State/Territory Disability Agreement and the National Disability Agreement (Cat. No. DIS 58). Canberra: AIHW.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2011b). Disability support services 2009-10: Report on services provided under the Commonwealth State/Territory Disability Agreement and the National Disability Agreement (Cat. No. DIS 59). Canberra: AIHW.

- Beer, A., & Faulkner, D. (2009). The housing careers of people with a disability and carers of people with a disability (Research Paper). Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Bittman, M., Hill, T., & Thomson, C. (2007). The impact of caring on informal carer's employment, income and earnings: A longitudinal approach. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 42(2), 255-277.

- Craig, L., Mullan, K., & Blaxland, M. (2010). Parenthood, policy and work-family time in Australia 1992-2006. Work, Employment and Society, 24, 1-19.

- De Vaus, D., Gray, M., Qu, L., & Stanton, D. (2011, 6-8 July). Australian women's retirement income and assets: The role of employment, fertility and relationship history. Paper presented at the Australian Social Policy Conference, Social Policy in a Complex World, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

- Gray, M., & Edwards, B. (2009). Determinants of the labour force status of female careers. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 12(1), 5-20.

- Hayes, A., Qu, L., & Weston, R. (2011). Families in Australia 2011: Sticking together in good and tough times. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Stuides.

- Llewellyn, G., Gething, L., Kendig, H., & Cant, R. (2003). Invisible carers: Facing an uncertain future. A report of a study conducted with funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council 2000-2002. Sydney: University of Sydney.

- Patja, K., Livanainen, M., Vesala, H., Oksanene, H., & Ruoppila, I. (2000). Life expectancy of people with intellectual disability: A 35-year follow-up study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 44(5), 591-599.

- Percival, R., & Kelly, S. (2004). Who's going to care? Informal care and an ageing population. Canberra: National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, University of Canberra.

- Pierce, G. (2007). Response to disability supported accommodation: A discussion paper for the Australian Government Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Deakin West, ACT: Carers Australia.

- Pierce, G., & Paul, P. (2010). Planning options and services for people ageing with a disability and their caring families: Submission to the Senate Community Affairs Committee. Footscray, Vic.: Carers Victoria.

- Productivity Commission. (2010). Disability care and support (Issues Paper). Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Productivity Commission. (2011). Disability care and support (Report No. 54). Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Schofield, H., Bloch, S., Herman, H., Murphy, B., Nankervis, J., & Singh, B. (1998). Family caregivers: Disability, illness and ageing. Melbourne: Allen and Unwin, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation.

- Sefton, T., Evandrou, M., & Falkingham, J. (2011). Family ties: Women's work and family histories and their association with incomes in later life in the UK. Journal of Social Policy, 40(1), 41-69.

- Senate Community Affairs References Committee. (2011). Disability and ageing: Lifelong planning for a better future. Canberra: Parliament of Australia Senate. Retrieved from <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate_Committees?url=clac_ctte/planning_options_people_ageing_with_disability_43/report/index.htm>.

- Strauss, D., Shavelle, R., Reynolds, R., Rosenbloom, L., & Day, S. (2007). Survival in cerebral palsy in the last 20 years: Signs of improvement? Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 86-92.

- Whiteford, P. (2009). Family joblessness in Australia: A paper commissioned by the Social Inclusion Unit of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Wittenberg, R., Pickard, L., Comas-Herrera, A., Davies, B., & Darton, R. (1998). Demand for long-term care: Projections of long-term care finance for elderly people. Canterbury, Kent: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent.

- Wittenberg, R., Pickard, L., Comas-Herrera, A., Davies, B., & Darton, R. (2001). Demand for long-term care for elderly people in England to 2031. Health Statistics Quarterly, 12, 5-17.

- Yates, J. (2007). Affordability and access to home ownership: Past, present and future? (Research Paper No. 10). Sydney: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. Retrieved from <www.ahuri.edu.au/publications/download/nrv3_research_paper_10>.

| More severe disability (%) | Milder disability (%) | All (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blackouts, fits or loss of consciousness | 6.8 | 4.7 | 5.8 |

| Chronic or recurrent pain or discomfort | 7.8 | 14.7 | 11.0 |

| Difficulty gripping or holding things | 12.7 | 3.8 | 8.6 |

| Difficulty learning or understanding things | 65.5 | 40.4 | 53.9 |

| Disfigurement or deformity | 6.5 | 4.7 | 5.7 |

| Limited use of arms and/or fingers | 6.9 | 2.6 | 4.9 |

| Limited use of legs or feet | 9.8 | 3.1 | 6.7 |

| Loss of hearing | 8.5 | 7.4 | 8.0 |

| Loss of sight | 4.2 | 2.6 | 3.5 |

| Mental illness | 27.6 | 4.3 | 16.7 |

| Nervous or emotional condition | 16.8 | 17.5 | 17.1 |

| Restriction in physical activities or in doing physical work | 24.2 | 18.7 | 21.6 |

| Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing | 12.7 | 12.6 | 12.7 |

| Speech difficulties | 41.0 | 8.0 | 25.7 |

| No. of observations | 707 | 611 | 1,318 |

Notes: Participants could provide multiple responses, so percentage totals may exceed 100%.

Source: SDAC 2009

| Age | Fully owned (%) | Purchasing (%) | Public housing (%) | Private rental (%) | Other housing (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | ||||||

| 60-64 years | 62.4 | 24.5 | 5.0 | 7.3 | 0.8 | 100.0 |

| 65-69 years | 74.3 | 13.9 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 77.9 | 9.3 | 5.4 | 6.2 | 1.2 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 82.2 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 1.2 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 84.7 | 7.1 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 79.5 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 78.0 | 10.1 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 1.1 | 100.0 |

| Mothers | ||||||

| 60-64 years | 65.7 | 15.8 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 1.0 | 100.0 |

| 65-69 years | 72.4 | 11.0 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 1.3 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 73.7 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 7.6 | 1.4 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 77.5 | 6.5 | 8.4 | 6.1 | 1.4 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 74.3 | 7.2 | 9.3 | 7.0 | 2.2 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 70.3 | 7.6 | 9.4 | 10.8 | 1.9 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 73.8 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 7.5 | 1.5 | 100.0 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations. Excludes those whose housing tenure was not stated (3% of fathers and mothers). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

| < $500 (%) | $500-999 (%) | $1,000-1,699 (%) | $1,700+ (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | |||||

| 60-64 years | 7.6 | 35.4 | 32.4 | 24.6 | 100.0 |

| 65-69 years | 8.4 | 46.7 | 28.9 | 16.0 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 9.3 | 57.1 | 23.3 | 10.4 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 11.1 | 61.1 | 21.2 | 6.6 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 9.8 | 60.0 | 22.8 | 7.3 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 17.5 | 53.1 | 24.3 | 5.1 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 9.8 | 53.9 | 25.1 | 11.3 | 100.0 |

| Mothers | |||||

| 60-64 years | 13.0 | 45.8 | 26.2 | 15.0 | 100.0 |

| 65-69 years | 15.2 | 53.5 | 22.0 | 9.3 | 100.0 |

| 70-74 years | 17.9 | 56.4 | 19.4 | 6.3 | 100.0 |

| 75-79 years | 18.9 | 59.0 | 17.5 | 4.7 | 100.0 |

| 80-84 years | 20.6 | 59.8 | 15.8 | 3.8 | 100.0 |

| 85+ years | 23.8 | 57.3 | 14.5 | 4.4 | 100.0 |

| Total (65+ years) | 18.1 | 56.4 | 19.0 | 6.4 | 100.0 |

Note: a Parent carers living with a son or daughter with profound or severe core activity limitations. Excludes those whose family income was not stated (9% of fathers and mothers). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: 2006 Census customised tables

| More severe disability a, c | Milder disability b, c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | |

| High population growth scenario | ||||

| 2010 | 47,496 | 79,564 | 39,930 | 74,976 |

| 2020 | 54,438 | 91,104 | 44,298 | 83,869 |

| 2030 | 62,087 | 103,363 | 50,291 | 94,891 |

| 2040 | 67,385 | 112,499 | 55,626 | 104,844 |

| Medium population growth scenario | ||||

| 2010 | 47,376 | 79,371 | 39,860 | 74,854 |

| 2020 | 52,336 | 87,885 | 43,271 | 82,067 |

| 2030 | 56,476 | 94,935 | 46,949 | 89,249 |

| 2040 | 59,490 | 10,0351 | 49,943 | 95,190 |

| Low population growth scenario | ||||

| 2010 | 47,276 | 79,213 | 39,811 | 74,770 |

| 2020 | 50,350 | 84,884 | 42,345 | 80,480 |

| 2030 | 51,247 | 87,174 | 43,855 | 84,156 |

| 2040 | 52,322 | 89,445 | 44,755 | 86,581 |

Notes: a People with profound or severe core activity limitations. b People with moderate or mild core activity limitations, or with an education or employment restriction. c The confidence interval is derived by applying to population projections the 95% confidence interval of the age-specific rate of children with a disability who live with their parents.

Source: SDAC 2009 and ABS (2008) population projections (Series B)

| More severe disability a, c | Milder disability b, c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | |

| High population growth scenario | ||||

| 2010 | 196,183 | 327,293 | 163,680 | 306,536 |

| 2020 | 228,170 | 380,645 | 184,567 | 348,639 |

| 2030 | 264,563 | 438,968 | 212,824 | 400,620 |

| 2040 | 291,393 | 484,686 | 238,826 | 448,957 |

| Medium population growth scenario | ||||

| 2010 | 195,206 | 325,691 | 162,988 | 305,293 |

| 2020 | 216,013 | 361,652 | 177,786 | 336,443 |

| 2030 | 234,567 | 393,095 | 193,853 | 367,777 |

| 2040 | 248,980 | 418,494 | 207,625 | 394,782 |

| Low population growth scenario | ||||

| 2010 | 194,215 | 324,068 | 162,296 | 304,049 |

| 2020 | 203,985 | 342,929 | 171,024 | 324,390 |

| 2030 | 206,090 | 349,656 | 175,559 | 336,406 |

| 2040 | 209,822 | 357,514 | 178,412 | 344,492 |

Notes: a People with profound or severe core activity limitations. b People with moderate or mild core activity limitations, or with an education or employment restriction. c The confidence interval is derived by applying to population projections the 95% confidence interval of the age-specific rate of children with a disability who live with their parents.

Source: SDAC 2009 and ABS (2008) population projections (Series B)

List of tables

Table 2: Age distribution of parent carers, 2009

Table 3: Ageing parent carers in Victoria and Australia, by age and gender, 2006

Table 4: Ageing parent carers without a partner, Victoria and Australia, by age and gender, 2006

Table 5: Housing tenure status of ageing parent carers, Victoria, by age and gender, 2006

Table 6: Weekly family income of ageing parent carers, Victoria, by age and gender, 2006

Table 7: Ageing parent carers who were employed, Victoria and Australia, by age and gender, 2006

Table A2: Housing tenure status of ageing parent carers, Australia, by age and gender, 2006

Table A3: Weekly family income of ageing parent carers, Australia, by age and gender, 2006

List of figures

Figure 1: Female employment rates, by age and mother carer status, 2009

Dr Lixia Qu is a Senior Research Fellow and Dr Ben Edwards was the Executive Manager of the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children at the Australian Institute of Family Studies at the time of writing. Professor Matthew Gray is Professor of Public Policy at the Australian National University.

The research reported in this paper was commissioned by Carers Victoria. We are grateful for comments and advice from Carers Victoria staff, especially Gill Pierce and Emma Collin. We wish to thank David de Vaus for commenting on earlier draft and Lan Wang, the Institute’s Publishing Manager, for both editing and polishing this work. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Australian Government or Carers Victoria.

Qu, L., Edwards, B., & Gray, M. (2012). Ageing parent carers of people with a disability. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-921414-92-3