An ear to listen and a shoulder to cry on

The use of child health services in Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth.

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

November 1990

Abstract

The first stage of the Institute's Early Childhood Study examined among other things the current use of child health services in Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth, and assessed the extent to which these services were meeting the needs of infants and young children. A questionnaire was sent through the school system to mothers of five year old children in their first year of school. There were 8446 respondents. This article examines: how many mothers use the service, their ethnic and working background; the mothers' views of child health services; and a brief history of child health services in Australia with particular focus on South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia. A comparison is made between Australian child health services and the British and French systems.

AIFS Senior Research Fellow, Gay Ochiltree, reports on an important aspect of the Institute's Early Childhood Study, conducted in conjunction with the Children's Services Office in South Australia, the Office of the Family in Western Australia and with assistance from the Commonwealth Department of Community Services and Health

The aim of child health services in Australia is to improve the health and wellbeing of infants and young children so that optimal physical, emotional and social development is possible. Services are free and available to all, essentially through locally based centres.

Hospitals notify local councils of births, and fully- qualified nurses in the local child health service make the first contact with mothers either by hospital or home visit. Advice on feeding and the general day-to-day care of the baby is given; health checks of such things as vision, hearing, language and general development are routinely provided, as is information about immunisation and health care; and mothers are put in touch with other relevant services. Some centres run parenting education sessions, particularly for parents of first babies, and in some centres there are play groups for young children and toddlers. Services differ somewhat from one area to another, often due to differences in the way the nurses in charge see the role of the centre.

The child health service in each State provides every mother with a booklet in which to record her child's development, immunisation, and health, and in addition has brochures for new parents explaining the functions and encouraging the use of child health services. Available in major community languages as well as in English, these are distributed by hospitals and other centres.

Attempts are made to go beyond the bounds of basic child health, nutrition and developmental issues, and into the realms of parenting and family support.

In 1988 infant mortality was 8.7 per thousand live births (ABS 1988), a great improvement from the early days of child health services in Australia (see boxed insert). Infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies are no longer major problems, and most women are better educated on such matters these days. However, there are other changes affecting the care of young children and the social context in which they are reared which have implications for the design of child health services.

Among such changes are the trend to small families, the likelihood of mothers to be in the paid workforce before the child goes to school, the increase in divorce and separation (and therefore the number of single parents rearing children alone), and increased poverty, much of which is associated with living in a female-headed single-parent family after divorce, although there has also been an increase in the proportion of unemployed couples with children living in poverty. Another significant change has been in the composition of Australia's population - 3.5 million immigrants of mixed races and cultures have arrived here since World War II, and agencies and institutions must acknowledge the special needs and cultural differences of these migrant groups, especially those for whom English is a second language.

Respondents in the Institute's Study

The first stage of the Institute's Early Childhood study examined among other things the current use of child health services in Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth, and assessed the extent to which these services were meeting the needs of mothers of infants and young children in the context of contemporary Australia. A questionnaire focusing on care of the child in the pre-school years was sent through the school system to mothers of five- year-old children in their first year of school.

The 8446 mothers who returned their questionnaires to the Institute took part in this first stage of the study: the greatest proportion, 66 per cent (5597), lived in Melbourne, 16 per cent (1383) lived in Adelaide, and 17 per cent (1466) in Perth; 21 mothers removed identification of the city from the questionnaire. Respondents were recruited through the State school system (85 per cent), the Catholic school system (10 per cent), and Independent schools (4 per cent). Most children in the sample were born in 1982 (48 per cent), 1983 (52 per cent), and 21 children (.2 per cent) were born in 1984. The sample was weighted to make it representative of the population of five- year-olds in the three cities combined.

Information was collected on background factors such as marital status of the mother, the child's position in the family (birth order), whether a language other than English was spoken in the home, mother's work status, parents' education, and type of family.

Who uses Child Health Services?

Mothers were asked three questions about their use of child health services for the particular child - how often they used the service, how helpful it was, and what they thought about the child health service in their State.

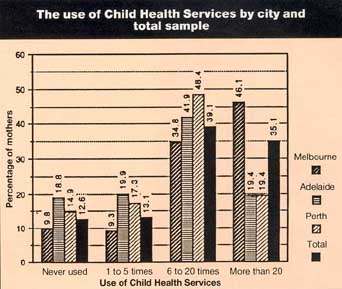

Overall, most mothers (87 per cent) had used the service. The accompanying figure shows the frequency of use of services for each city and the total sample: a greater percentage of Melbourne mothers (90 per cent) had been users than had Adelaide mothers (81 per cent) or Perth mothers (85 per cent). Just over a tenth of mothers in the total sample (13 per cent) had not used child health services for the child involved in the study.

As might be expected, mothers of first born children were more frequent users than the more experienced mothers of later born children; 44 per cent of mothers of first born children used child health services more than 20 times, compared with 33 per cent of mothers of middle children, and 26 per cent of mothers of last born children.

Mothers from families where a language other than English is spoken generally made less use of child health services than other mothers, with only 26 per cent using the service more than 20 times, compared with 37 per cent of mothers from English-speaking homes.

Mothers of pre-school children are increasingly entering the workforce before their children start school. Of the 8446 mothers in the study, 1210 (14 per cent) returned to work in the first year of their child's life. A greater percentage of mothers working medium (20 to 29 hours per week) or long hours (more than 30 per week) did not use child health services at all, or used them only a few times, compared with mothers who did not work at all, or who worked shorter hours.

Mothers' Views of Child Health Services

Mothers were asked: 'What do you think about the Child Health Service?' (the appropriate name for the service in each State was used), and they could write whatever they liked. To examine underlying patterns in these responses, 10 per cent of the sample (sufficient to represent the trends) was selected randomly and coded for analysis.

Of this random sample, 95 per cent of mothers who had used child health services found them helpful: 42 per cent found them very helpful and 53 per cent helpful.

Mothers who were helped

For mothers who felt that they had been helped, responses to the question 'What do you think about the child health service?' fell into three major categories.

One: the importance of the service for first-time mothers and for young babies was referred to by 31 per cent of mothers.

'It's a very necessary service for mothers with their first child. I have found mothers feel very housebound and lacking in confidence with no positive feedback until they visit the clinic. I feel the service needs to choose the clinic sisters more carefully, and to publicise their wider range of services more.'

'The service for me was more useful for my first child - I was more experienced next time - and it is indispensable for mothers lacking confidence and suffering depression.'

Two: the social value of child health service and what it does or does not provide for mothers and the community in general was referred to by 31 per cent of mothers.

'It is an excellent support and resource for all mothers and families, especially for the first born and those without extended families. It is also a great service because it is free, and because it is accessible to mothers without transport. It is less threatening than hospital and doctors' clinics, and it is an advantage to be able to have home visits. Also, it is important for mothers to be able to relate to other women and other mothers.'

Three: the quality of the advice, the quality of staff training and/or a description of the service received by the respondent was mentioned by 29 per cent of mothers.

'I think the Maternal and Child Health Services are wonderful - without my infant welfare sister I would have had trouble coping with my baby. Not only are they a great help with the baby, they also care greatly for the mother and her individual problems, giving confidence, which is important.'

'It is an invaluable service, offering sensible advice. The phone service is also good, especially with a first child, when to go to the doctor or not can be a problem.'

Mothers from homes where a language other than English was spoken who had used child health services and found the service helpful voiced opinions similar to those from mothers in English-speaking homes.

Mothers who were not helped

A small minority of mothers (5 per cent) who had used child health services found them to be not helpful. Although this group of dissatisfied users is small, information about such mothers and the reasons for their dissatisfaction are important for service providers if they are to improve the service. This group of mothers was not distinguished by any demographic measures.

Of the mothers who felt they were not helped, 28 per cent referred to personal qualities of the staff: that they lacked the personal experience of motherhood, that they had their own ideas about what was right and did not respond to the particular circumstances of mother and child, and that they were too 'bossy'. A theme which came through, particularly among mothers who were not helped, but also to some extent with mothers who were helped, was the fact that much depended on the particular sister and centre, and that the service could vary a great deal.

The views of mothers in homes where languages other than English were spoken were examined to see if their experiences were the same as other mothers who have not found the services helpful, or if they had special reasons for feeling that they were not helped. The following response, typical of this group, shows that the criticisms were similar to those of mothers who use English at home.

'The nurse was not very helpful and although my English is quite good she treated me as if I did not understand anything. I left the place without being any less worried about my child's health.'

Conclusion

Over the period of time that Australian child health services have been operating, there have been reviews and reorganisation of the various services at different times, but essentially their aim has been to remain educative and supportive services available to all mothers with infants and/or young children, rather than being intrusive and supervisory.

Traditionally in this country, child health services have been innovative and inventive in servicing the needs of mothers and infants in isolated areas (see boxed inset). Some modern-day mothers in city locations may also need services which are just as inventive and which make use of locations other than clinics. Consultation with ethnic community groups and low income support groups may identify new approaches to meeting their needs. Provision of more flexible opening hours for centres may be necessary to enable working mothers to visit at convenient hours.

Child health service providers should take note of the criticisms of some of the users. The study found that some nurses appear to be too rigid and to operate 'by the book'. To what extent do these nurses understand the problems of families in modern society where increasingly mothers of very young children are entering the workforce and leaving their children in the care of others, where many families come from very different cultures with different values and ways of doing things, and where many speak a language other than English at home?

Refresher courses which keep nurses up to date not only on health matters but also on what is happening in families and society are essential. Australian society has changed, and Australian families have changed. Trying to balance work and family demands is a problem for many parents, trying to adapt to a new and often strange society is a problem for others, while low income places pressures on parents and is linked with low self- esteem. Child health services and individual nurses must be sensitive to these difficulties.

Child health services are used by most mothers, and most believe it is an important and worthwhile support. Nevertheless, the needs of the mothers who felt that they had not been helped must not be forgotten as their views indicate some areas which need improvement. But perhaps the final comment should come from a mother whose experience was close to ideal.

'The sisters gave help, advice, support ... there was always an ear to listen and a shoulder to cry on.'

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (1989), Labour Force and Other Characteristics of Families, Australia, June 1989, Catalogue No.6224.0.

- ABS (1988), Deaths Australia, Catalogue No.3302.0.

- Campbell, Dame Kate (1976), 'The Progress of Infant Welfare Services in Victoria Over the Past Fifty Years', Paper presented at the Jubilee Conference on Maternal and Child Health, Melbourne.

- CAFHS (1989), Celebrating Eighty Years of Community Child Health Care, Child, Adolescent and Family Health Service, Adelaide.

- Child Health Services in Western Australia (c.1972).

- Foster, M. (1988-89), 'The French puericultrice', in Children and Society, No.4, pp. 319-334.

- Gandevia, Bryan (1978), Tears Often Shed: Child Health and Welfare from 1788, Permagon Press, Sydney.

- MacDonald, W.B. (1975), 'Why mothers do not bring their children to child health centres', Paper presented at Liberal Party of Australia (West Australia Division), State Women's Council Current affairs Convention, 26-27 May.

- Mayall, B. and Foster, M. (1989), Child Health Care: Living With Children, Working for Children, Heinemann, Oxford.

- Poulter, Jean (1976), 'The Part Played by Nurses', Paper presented at the Jubilee Conference on Maternal and Child Health, Melbourne.

- Zelizer, V. (1985), Pricing the Priceless Child, Basic Books, New York.