How is it going to affect the kids?

Parents' views of their children's wellbeing after marriage breakdown

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

November 1990

Abstract

In 1987, 523 divorced parents were surveyed for the Australian Institute of Family Studies' Parents and Children after Marriage Breakdown Study. This was a follow-up survey of parents who were first interviewed for the Economic Consequences of Marriage Breakdown Study. The parents' views were elicited about the wellbeing of their children over the course of the marriage breakdown and in the longer term and the importance of the children in the lives of the parents. The survey indicated that parents considered their children's wellbeing to be adversely affected prior to separation and even more seriously affected during the early separation period. In 1984, resident parents were highly satisfied with their children's wellbeing and they remained so another three years later. In comparison, non-resident fathers were less content in the longer term. Indeed, while the majority of resident parents in 1987 believed their children were better off as a result of the separation and divorce, only one-quarter of non-resident fathers considered this to be the case.

Is it better to stay together for the sake of the children, or are children better off when released from a home life characterised by parental conflict and unhappiness? What happens to the relationship between the children and parent who lives apart from them? AIFS Research Fellow, Ruth Weston, reports.

'Nothing prepares you for what is going to happen once you separate - for instance, how it's going to affect the kids.'

You never get over wondering whether you have done the right thing by the children.'

These comments of two parents who participated in the Institute's follow-up study of the consequences of marriage breakdown encapsulate society's uncertainties concerning the effects of separation upon children. Two other parents expressed these worries as follows:

'Emotionally, I'm a lot better off. The only trouble is, what damage are you doing to the children?'

'I suffered a lot of guilt regarding the children. I made the decision to separate for myself and for them, and its difficult to know if you've made the right decision for them.'

The Institute's follow-up survey of 523 divorced parents elicited views about the wellbeing of the children over the course of marriage breakdown and in the longer term. The parents were divorced in the Melbourne Registry of the Family Court of Australia in 1981 or 1983, and were interviewed in 1984 (AIFS Economic Consequences of Marriage Breakdown study) and again in 1987 (AIFS Parents and Children after Marriage Breakdown study). They had been married for five to fourteen years and had two dependent children from this relationship, whose average ages were around 13 and 15 years at the time of the second survey. Details of the study can be found in Funder (1984, 1989).

Here, two broad issues are examined: first, parents' feelings about their children's wellbeing and about the overall impact of the divorce on their children; and, second, the importance of the children in the lives of the parents over time.

The sample for this analysis is restricted to cases where the two children were living together, either with their mother or father. For 83 per cent of the women and 65 per cent of the men, the two children were living with their mother, and attention will be largely directed to these two groups, called 'resident mothers' (240 cases) and 'non- resident fathers' (153 cases). Another 13 per cent of men were living with both children. Trends for these 'resident fathers' (31 cases) will also be discussed to clarify whether differences observed between the first two groups can be attributed to gender or to resident status. However, given the small number of cases, results for this group should be considered with caution.

Measuring Satisfaction

During the two interviews, parents were asked to rate their satisfaction with life as a whole and with specific domains of life (including children's wellbeing) on nine-point scales ranging from (1) 'terrible' to (9) 'delighted'. These scales were used by Headey and Wearing (1981) in a national survey of a random sample of Australians, and in follow- up surveys of their Victorian subsample. Headey and Wearing found that people are inclined to indicate 'moderately high satisfaction' (average ratings between 6.0 and 7.0) with life in general and with most of aspects of life. Exceptions include their children and marriage, about which even greater satisfaction is reported, and federal, state and local governments, which yield 'relatively low satisfaction' (average ratings of below 6.0). These average ratings have been stable over time.

Parents used the scales to indicate their level of satisfaction during four periods - the last year of their marriages, the first three months of separation, and at the time of each survey (1984 and 1987). Satisfaction for the first two of these periods, just before and after separation, was recalled in the 1984 interview. These perceptions of past feelings may well have been coloured by current circumstances and recent events.

General Impact of Separation

Figure 1 shows the proportions in each parent group in the second of the two surveys, in 1987, who said that, on balance, their children were better off or worse off as a result of the separation and divorce, or that the children were much the same as they would have been had no separation occurred: 5-6 per cent of resident mothers and non-resident fathers were too uncertain to answer this question.

The views of resident mothers and fathers are remarkable for their similarity: the majority said their children were better off and few said they were worse off. Non-resident fathers were more evenly divided in their opinions, with 36 per cent reporting a neutral effect, 32 per cent claiming a negative effect, and 26 per cent stating that their children were better off.

The overall pattern of trends for the three groups suggests that it is resident status rather than gender which leads to the differences between opinions of resident mothers and non-resident fathers. In another Institute study with a much larger sample than the present one (Harrison, Snider and Merlo 1990), the importance of resident status was also found to be greater than gender in relation to attitudes about maintenance payments.

Slightly higher proportions of non-resident fathers considered their children to be worse off if their former wives were single or in a de facto relationship (with 39 per cent claiming a negative effect) than if their wives had remarried (with 22 per cent claiming a negative effect). However, the non-resident fathers' own marital status was unrelated to their views about the impact of the divorce on their children. Age of the children, distance between residences, frequency of access visits, and maintenance payments did not affect the views of these men about the impact of the divorce.

Satisfaction with Children's Wellbeing and with Life as a Whole

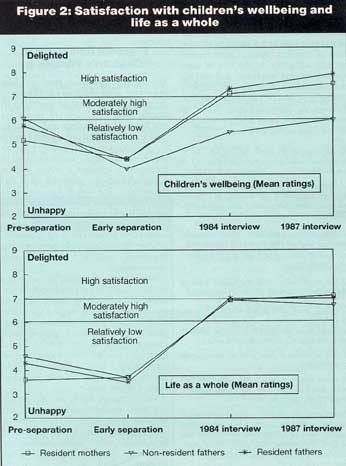

Figure 2 shows the average satisfaction with the wellbeing of the children of the first marriage for the four periods investigated. In order to place these views in perspective, parents' satisfaction with life as a whole (or 'morale') is also depicted.

The lower graph shows that parents found the pre- separation and early post-separation periods demoralising, but by 1984 satisfaction had improved to levels close to the national average of 7.0 (Headey and Wearing 1981) and the picture changed little thereafter. Mothers appeared more demoralised than fathers prior to separation, but when separation occurred, fathers' morale fell. This can be explained by the typical role played by men and women in the decision to separate: consistent with results from the Institute's earlier study of divorced people (Weston 1986a), those who initiated the separation (predominantly women) were more demoralised before than after separation, while the opposite was the case for those who did not (predominantly men).

In general, satisfaction with the children's wellbeing followed a pattern similar to that for satisfaction with life. Whereas Headey and Wearing found that Australians are inclined to express high satisfaction with their children (a slightly different question), divorced parents recalled moderate or low satisfaction during the pre-separation period, and became increasingly dissatisfied about their children's wellbeing immediately after separation.

Resident parents expressed high satisfaction in 1984, and were even more positive about their children's wellbeing in 1987, but the children's longer-term wellbeing did not appear as rosy to non-resident fathers. Even by the time of the second survey, in 1987, these men felt no happier with their children's wellbeing than they had felt during the turbulent pre- separation period. Irrespective of whether they initiated the separation, all but one group (resident mothers who decided to separate) saw their children's wellbeing as plunging immediately after separation.

Figure 2 shows average trends, and of course there are exceptions to these: the following comments highlight the diversity of views.

'Initially the separation was very traumatic. I felt a complete failure and I felt very bad as far as the kids were concerned. They were bewildered by the whole thing and I felt I had let them down. What we were doing to the kids was devastating.' (Non-resident father)

'I've accepted it. It's the kids that suffer. They are not happy being with her and her new partner.' (Non-resident father)

'The breakdown of marriage has done nothing but good for me and the children. I felt no regrets about leaving - we weren't happy in the marriage.' (Resident mother)

'My children are coping well. They both now accept the situation and I find the added responsibilities they have had to take on have made them more mature and independent than most children their age.' (Resident mother)

'You feel you have failed the children - for not having Daddy around.' (Resident mother)

The difficulties encountered at the time of separation included handling the distress of children, spouse, relatives and friends, adjusting to the loss of one's spouse, moving residence, and making decisions about custody and property during a period of emotional turmoil. Women in particular were likely to mention problems of being a sole parent or financial difficulties.

'It has changed my whole life - the lack of money means that you and the children can't do what other families do.' (Resident mother)

'Although my ex-husband hadn't a lot to do with the discipline of the children, he supported me in all these things and I miss that badly.' (Resident mother)

For men, problems often centred around loss of children and family life, as well as diminished influence on their children's lives.

'I lost the chance of seeing my children grow up day by day - nothing in life can replace that.'

'To walk away after a marriage of 15 years, after living in a family situation with a house, wife and kids, and move to a room in somebody else's house - it's a very emotional time.'

'I still can't come to grips with not coming home to my children.'

'I would like to make decisions about the children, but my former wife ignores my comments about school, sport, health, etc.'

'She changed the children's surname to her maiden name without my consent. She is turning them against me and telling them to call her new partner, not husband, but "Dad". She is making the children feel as though I exist only to pay maintenance.'

Many parents underestimated the decision-making rights and responsibilities typically held by the non-resident parent (Weston and Harrison 1989). Unless there is an order to the contrary (which occurs in a minority of cases), each parent is a guardian of his or her children, and each has joint custody of them until they reach the age of 18 years. That is, in the majority of cases, both parents have the right and responsibility to share in decisions affecting their children's daily care and control (custody) and in decisions affecting their upbringing or long-term welfare (guardianship). Ignorance about these legal matters would compound the frustrations of some non-resident fathers who continued to care deeply for their children. Such ignorance may also lead to further withdrawal from the lives of the children.

Despite the difficulties reported by non-resident fathers, Figure 2 suggests that they tended to be as content with life as resident parents. In other words, most seemed to have adjusted to their circumstances. The implications of this will now be considered.

Personal Relevance of Children's Wellbeing

The central question here is: how important is the children's wellbeing to the parents' own sense of wellbeing or morale over the course of separation and beyond? As Lazarus and Folkman (1984) have pointed out, commitments (or values, needs or goals) play an important but often overlooked role in determining whether a person will be distressed or happy about events or circumstances. The 'stakes' a person has in any situation are determined by the strength of commitments affected. Thus, adjustment to perceived harms or losses often entails changing priorities, so that the unattainable becomes less important, perhaps replaced by new commitments.

Assessment of personal priorities is a complex matter, for people can be unaware or only dimly aware of some commitments which shape a great deal of their behaviour, for instance, possible motives to attain power, excel competitively, or to receive social approval. Further, the importance of some things, such as being in sound health, may only become apparent when they are unmet.

Other things being equal, people will feel generally content with life when all seems well with those domains held important; they will feel distressed or unhappy when these domains are threatened. This was expressed by one resident mother, in relation to the importance she attached to her children's wellbeing:

'The children suffer as a result of marriage breakdown. To me, the children come first; their needs and wellbeing are paramount to my needs.'

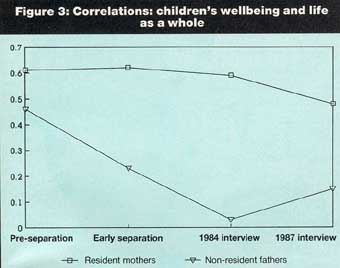

Correlation coefficients were derived to assess the strength of the relationship between levels of satisfaction with children's wellbeing and with life as a whole (or 'morale'). The stronger the correlation the closer is the relationship, with those unhappy about their children's wellbeing feeling unhappy with life, and those happy about their children's wellbeing expressing happiness with life.

Correlations do not necessarily imply the existence of a causal connection, and if there is a cause, it is likely to be two-way, with the happy tending to view all domains of life with 'rose-coloured glasses', and the unhappy looking upon their lives more negatively by virtue of their unhappiness. However, research by Headey and Wearing (1981) and by the Institute (Weston 1986b, 1988) suggests that this approach is a useful means of gaining insight into the nature of priorities. Figure 3 shows the correlations between satisfactions with children's wellbeing and with life as a whole for the four periods assessed, for resident mothers and non- resident fathers.

Studies of married people provide correlations of around .4 between satisfaction with children or children's wellbeing and life as a whole (Heady and Wearing 1981, Weston 1988). In comparison, the importance of the children in the lives of resident mothers appeared to be elevated before and immediately after separation, and although the relationship had weakened by the second survey in 1987, the overall pattern suggests that children's wellbeing remained an important component of mothers' satisfaction with life.

Prior to the break-up, the children also seemed important in the lives of non-resident fathers, but this importance decreased dramatically. By 1984, children's wellbeing did not seem a relevant component of the fathers' morale. The correlation for 1987 was a little larger than that for 1984, but still small - too small to predict fathers' morale on the basis of their views about their children's wellbeing.

With only 31 resident fathers, correlations for this group will be unstable, but the pattern of post-separation results was closer to that for resident mothers than non-resident fathers. In other words, it appears that resident status rather than gender once again explains the results, although it would be unreasonable to conclude that results for non- resident mothers would match those obtained for non- resident fathers.

Correlations between satisfaction with life and seven other domains (household income, housing, material circumstances, job, freedom/independence, acceptance/inclusion by others, and respect/recognition received) were also derived, but none showed the striking loss in importance to non-resident fathers evident for children's wellbeing. For these men, children's wellbeing appeared to be the second strongest commitment pre- separation (second to freedom/independence), but during the two survey periods, it was the weakest.

These results suggest that non-resident fathers had lost much of the personal involvement which linked their children's wellbeing to that of their own.

Perceived Closeness and Involvement with the Children

In the second survey, in 1987, parents were asked to rate their levels of involvement with and closeness to each child (from 1 'not at all' to 5 'very'); these were combined into a single scale. Resident mothers reported the highest level of closeness/involvement, and non-resident fathers the lowest. Average ratings of resident fathers were closer in value to those of resident mothers than to non-resident fathers. As one father explained:

'The children grow away from the parent they're not with, and generally lose contact. The non-custodial parent can't make any impression on the children in the time they have together and loses touch with what the children like to do. Access is harder as the children start leading their own lives.'

Some resident mothers wished their former husbands had less contact with the children, but regrets about this were more common:

'I'd like him to at least ring the children if he can't organize a visit, so that they can develop a relationship with their father. I'd like a break for myself.'

'I would like their father to get to know the children better and to take more interest in them, for instance, attend school meetings.'

Non-resident fathers who reported relatively low closeness/involvement with their children were significantly less satisfied with their children's wellbeing than their counterparts who reported higher closeness/involvement, but there was no difference between these groups in their satisfaction with life as a whole.

Conclusion

Parents considered their children's wellbeing to be adversely affected prior to separation and even more seriously affected during the early separation period. In 1984, resident parents were highly satisfied with their children's wellbeing and they remained so another three years later. In comparison, non-resident fathers were less content in the longer term. Indeed, while the majority of resident parents in 1987 believed their children were better off as a result of the separation and divorce, only one-quarter of non-resident fathers considered this to be the case.

However, the importance of children's wellbeing to non- resident fathers dissipated, reflecting the adjustment of these men to the loss of their children. This is hardly surprising, given the often strained nature of access visits and the minimal control fathers felt they had over decisions affecting their children. Both resident and non-resident parents should be given well-defined guidelines about their custody and guardianship status.

The exclusion of children from the world of their fathers is a matter for concern not only for most men, but also for most children. Resident mothers, being more in touch than their former husbands with their children's feelings, often regretted this loss experienced by the children.

The overall pattern of results is consistent with the tendency for non- resident parents to pay inadequate maintenance prior to implementation of the Child Support Scheme (Harrison and McDonald 1988).

This discussion has centred upon children's wellbeing in general. One community concern which has received a great deal of attention is the impact of marriage breakdown upon children's schooling, and this matter is taken up by Christine Millward elsewhere in this issue.

References

- Harrison, M. and McDonald, P. (1988), 'Parents and children after marriage breakdown: the price of child maintenance', Paper delivered at the Bicentenary Family Law Conference, Melbourne, March 16-20, Business Law Education Centre, Melbourne.

- Harrison, M., Snider, G. and Merlo, R. (1990), 'Who Pays for the Children? A First Look at the Operation of Australia's New Child Support Scheme, Monograph No.9, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Funder, K. (1986), 'The design of the study', in P. McDonald (ed.), Settling Up: Property and Income Distribution on Divorce in Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies and Prentice-Hall, Sydney.

- Funder, K. (1989), 'Financial support and relationships with children', Report No.6, Child Support Scheme Evaluation Study, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Lazarus, R.S. and Folkman, S. (1984), Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, Springer, New York.

- Weston, R. (1986a), 'Factors associated with adjustment after marriage breakdown', Paper delivered at the Second AIFS Australian Family Research Conference, in Melbourne, 26- -28 November.

- Weston, R. (1986b), 'Money isn't everything', in P. McDonald (ed.), Settling Up: Property and Income Distribution on Divorce in Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies and Prentice-Hall, Sydney.

- Weston, R. (1988), 'Life concerns and sense of wellbeing', in N. Barr, R.

- Weston and G. Wyatt, The Tragowel Plains: A Study of an Agricultural Community, Sponsored by the Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Melbourne.

- Weston, R. and Harrison, M. (1989), 'Divorced parents' understanding of their legal rights or responsibilities towards their children', Paper delivered at the Third AIFS Australian Family Research Conference, at Ballarat ollege of Advanced Education, 26-29 November.