Institute undertakes three-year study into Australian living standards

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

August 1991

Abstract

Since the early 1980s the Australian government has aimed to improve the living standards of families and reduce poverty and inequality through income support measures, wages policy and taxation reforms. Recently, however, there have been discussions about the contribution of factors other than income to living standards and a renewed interest in families' 'non-incoming' needs, such as needs for employment, housing, education, health care and transport. This has focused attention on locational differences in living standards, since families may have similar incomes but there may be differences in their access to employment and services according to where they live. Arising out of this, the Australian Institute of Family Studies has been funded by the Federal Government to undertake a major study of the living standards of families in a number of different local areas of Australia, including some urban fringe, middle and inner city areas of Sydney and Melbourne, an outer area of Adelaide and three country areas. This paper discusses the theoretical framework for the study, which was developed from issues arising from a review of the international literature on living standards' research. It also describes the methodology of the study.

Measuring Living Standards in Australia

In a country as culturally and geographically diverse as Australia, the decision to undertake a comprehensive study of living standards raised challenging questions of theory and methodology. AIFS Fellow Helen Brownlee and Deputy Director (Research) Peter McDonald describe how the study has been set up.

In Australia, concerns about poverty and adequate living standards have focused mainly on Government policies to improve the adequacy of family incomes. Recently, however, the focus has widened due to renewed interest in other needs, such as for health care, housing and transport (Cass 1989; ALP Left 1990).

There are also concerns about locational differences in living standards, particularly that families may be forced to move to the urban fringes of large cities because of cheaper housing, but, as a result, they may face inadequate access to employment and services.

For these reasons, the Commonwealth Government has contracted the Institute to undertake a study of the living standards of families in 12 different areas across the country.

In order to conduct the Institute study, it was necessary to develop a conceptual framework that would enable the contribution of employment and services to living standards to be assessed and locational differences to be examined. In developing this framework, the international literature was reviewed to examine how other researchers had measured living standards (Brownlee 1991)

On the basis of this review, it was decided that the Scandinavian 'level of living' approach, in which living standards are examined according to a number of different components or 'spheres of life', provided the most suitable analytic framework for the study (Erikson and Aberg 1987; Erikson and Uusitalo 1987).

Using this framework, a broad range of indicators of living standards is to be examined in terms of 14 'spheres of life': health, employment, housing, economic resources, transport, education, recreation, the physical environment, security, community services, social and political participation, access to information, family relationships and personal wellbeing.

Although the Scandinavian studies have used the 'spheres of life' approach to collect some information about access to services, little information appears to have been collected about the use of services, except in the area of health care (Kjellstrom and Lundberg 1987). The 'sphere of life' approach, however, does provide a suitable framework for the collection and analysis of information about both access to and the use of services.

The approach also enables locational differences in living standards to be examined, and the living standards of different groups, such as people from non-English-speaking backgrounds and Aboriginal people, to be compared with those of the rest of the population according to the same measures.

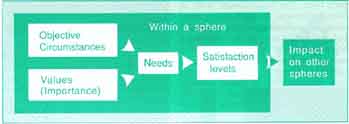

The following model is being used in the study to examine Australian living standards.

The model provides a framework to collect information about a broad range of objective circumstances, such as respondents' state of health and their access to and use of health services in the sphere of health, or their income, assets and access to other kinds of financial support in the sphere of economic resources.

One fundamental criticism of the measurement of living standards is that researchers have set standards or values for the population they are studying which the population may not, in fact, hold or accept. The Institute study adopts an approach similar to that of Mack and Lansley (1985) and takes respondents' values into account. A list of material items, activities and indicators describing the characteristics of the various services was drawn up by examining the relevant literature and consulting with people working in each 'sphere of life'. Respondents will be asked not only whether they possess an item or participate in an activity but also about the importance of these items or activities to them. Similarly, they will not only be asked about their use of a service, but also what is important to them in relation to the provision and delivery of that service. This approach aims to look at living standards from the respondents' perspective, rather than imposing standards on them.

Many studies have measured living standards in terms of 'meeting needs' (Townsend 1979). In some instances, 'needs' are universal, such as the need for food, shelter and a basic education. In other instances, individuals will have particular needs, such as for health care or transport. In assessing living standards, it is important that information on access to and the use of services is balanced with information on the need for services. In the AIFS study, objective measures, such as health status, which indicate needs will be obtained in addition to respondents' perceptions of their needs, such as unmet needs for medical or dental care.

Although it has been argued that only objective measures of living standards are of interest (Erikson and Aberg 1987; Ringen 1984), other researchers argue that the more subjective consequences of policies should be taken into account (Campbell, Converse and Rodgers 1976; Naess and others 1987). It was decided that for the purposes of this study, it was important to measure the subjective experiences of living standards and to relate this to objective conditions. Two private spheres of life are therefore included in the study: family relationships and personal wellbeing. Respondents will be asked to rate their satisfaction with all aspects of their living standards: their material possessions, the activities they pursue and various characteristics of the services they use.

In examining the contribution that services make to living standards, it is important to focus on the impact of services, or the lack of them, on people's lives. The Scandinavian 'level of living' approach, in which living standards are analysed according to a number of different components, provides a framework that enables systematic analysis of the impact of services on different 'spheres of life'; for instance, how the provision of public housing affects housing conditions, and the impact of public transport on employment opportunities.

In examining the effect of location on living standards, none of the research has successfully dealt with the impact of regional variations in prices. In the Institute interviews, respondents will be asked about their housing, transport, education and child care costs, all of which may differ according to respondents' location.

As for other costs of living, it was originally planned to measure differences in commodity prices by compiling a comprehensive 'basket of goods' and pricing the basket in each of the 12 study areas. However, expenditure patterns vary considerably due to climatic variations and the availability of goods in different areas (ABS 1984). Items that may be important to people living in some areas, such as heating oil in Melbourne or Tasmania, are not used at all by people living in the Northern Territory or central Queensland.

It was decided, therefore, to draw up a restricted basket of goods commonly used in most households, such as bread, milk and the unit cost of gas, electricity and petrol, and to collect the price of these items to indicate regional cost variations.

Five hundred households will be selected at random in each of the 12 areas. Information will be obtained from both partners in two-parent families and from single parents by means of self-completion questionnaires and face-to-face interviews. Young people of secondary school age and above will also be asked to complete short questionnaires to obtain information on their opinions and attitudes.

In instances where there are language difficulties or literacy problems, all the information will be collected through face-to-face interviews. All Aboriginal interviews will be conducted face-to-face by an Aboriginal interviewer since Aboriginal people prefer to be interviewed by one of their own. Every effort is being made to ensure that disadvantaged people are not missed, as commonly occurs in household samples.

To complement the household interviews, the facilities and services available to families in each area will be surveyed. Basically, two types of data are to be collected for each service type: factual and assessment.

The factual data will consist of items such as the location of services and standard costs for their use. The assessment data will be collected from three sources: planners, service deliverers and users. These assessments will cover such items as the appropriateness of services and co-ordination with other services.

Services for the purposes of this data collection have been categorised under the following headings: general planning and development, history of the area, housing, education, transport, health, employment, children's services, leisure and recreation, family and community services, safety and security.

Also as part of the study, a statistical data base of indicators of family living standards across a broad range of areas in Australia is being constructed. This will enable the 12 areas in the study to be compared with others throughout Australia.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (1984), The Australian Consumer Price Index: Concepts, Sources and Methods, Catalogue No.6461.0, April.

- Australian Labor Party, Left Wing (1990), Community Development: A Strategy for the Fourth Term.

- Brownlee, H. (1991), Measuring Living Standards, AIFS Australian Living Standards Study, Paper No.1, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Campbell, A., Converse, P. and Rodgers, W. (1976), The Quality of American Life, Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- Cass, B. (1989), 'Expanding the concept of social justice: Implications for social policy reform', Paper presented at Department of Social Security Seminar 'Future Directions in Social Policy', Canberra, December.

- Erikson, R. and Aberg, R. (1987), 'The nature and distribution of welfare', in Erikson, R. and Aberg, R. (eds), Welfare in Transition: A Survey of Living Conditions in Sweden 1968-1981, Clarendon, Oxford.

- Erikson, R. and Uusitalo, H. (1987), 'The Scandinavian approach to welfare research' in Erikson, R., Hansen, E., Ringen, S. and Uusitalo, H. (eds), The Scandinavian Model, Welfare States and Welfare Research, M.E. Sharpe, New York.

- Kjellstrom, S. and Lundeberg, O. (1987), 'Health and health care utilization' in Eriksen, R. and Aberg, R. (eds), Welfare in Transition: A Survey of Living Conditions in Sweden 1968- -1981, Clarendon, Oxford.

- Mack, J. and Lansley, S. (1985), Poor Britain, George Allen and Unwin, London.

- Naess, S., Mastekaasa, A., Moum, T. and Sorensen, T. (1987), Quality of Life Research: Concepts, Methods and Applications, Institute of Applied Social Research, Oslo.

- Ringen, S. (1984), 'How people live', in Kjolsrod, L., Ringen, A., Skrede, K., Vaa, M. (eds), Applied Research and Structural Change in Modern Society, Norwegian Institute of Applied Social Research, Oslo.

- Townsend, P. (1979), Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living, Penguin, Harmondsworth.

This article is a synopsis of the paper presented to the Social Policy Research Centre conference in Sydney, 3--5 July 1991, and the British Social Policy Association conference in Nottingham, England, 9--11 July 1991.

ABOUT THE STUDY

Most Australians rank family life as the most important aspect of their lives, but simply being in a family is not a guarantee of a good life. Other needs have to be met, such as housing, transport, education, health, an adequate income and a healthy environment.

The Australian Living Standards Study will examine variations in the living standards of Australian families and help governments to plan services and facilities to suit families living in diverse locations.

The study will take place in 12 regions around Australia, with 500 families in each area selected at random for interviews that will cover, among various issues, the following:

- How housing standards vary.

- What are the employment opportunities, the level of income available and the cost of living in each area?

- What about transport, access to schools or higher education?

- Can respondents get health care when needed?

- Is there child care nearby, and care for ageing or invalid relatives?

- Are the facilities and opportunities for leisure, recreation, safety and security adequate?

- Are respondents happy with the environment in which they live?

Households will be invited to join the study if residents have children, whether still at home or not. Interviews are expected to take between one- and-a-half and two hours, with confidentiality assured.

Interviews are about to get underway after months of research and preparation. Interim reports will be issued as the surveys of each area are completed with a comprehensive final report on Australian family living standards expected by June 1993.

The study will cover five outer areas (Berwick and Werribee, near Melbourne, Campbelltown and Penrith near Sydney and Elizabeth/Munno Para near Adelaide), two mid- urban municipalities (Ryde in Sydney and Box Hill in Melbourne), two inner areas (City of Melbourne and South Sydney) and three outlying areas (Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory, Roma in Queensland and Renmark/Berri/Loxton in South Australia). The four Melbourne areas and Tennant Creek are the first to be surveyed.

At the same time, area studies will take place in all the municipalities, to examine and assess the services and facilities available.

The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet commissioned the Australian Institute of Family Studies to conduct the Living Standards Study in early 1990. More than $1 million has been committed to the study, including funding from the Department for Primary Industries and Energy to extend the study to country areas.

The Australian Living Standards Study is a landmark in research, asking people their point of view about practical day-to-day matters, as well as the expectations and hopes they have for their families.