Taxation and family income

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

September 1999

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

The author argues that governments need to redirect money from single people to families with children if families are to cope with the costs of raising children. She suggests that this used to happen, but that an unintended result of tax changes from the 1970s onwards, together with legislation intended to equalise wages for men and women, has been that families with children have become disadvantaged. We need to rethink our conceptions of 'social justice' to reflect the inequality of spending power between people with children and those without.

One of the results of the tax changes from the 1970s onwards has been that families with dependent children have been disadvantaged relative to the rest of society. We need to rethink our conceptions of 'social justice' to reflect the inequality of spending power between people with children and those without.

From his study of labourers' incomes in York at the turn of the century, Rowntree (1901) attributed poverty to life cycle factors rather than to low wages as such. The stages of the life cycle which correlate with the experience of poverty, he said, were: early childhood, when the family was dependent on parental income only; early parenthood, when the parents were solely responsible for family income; and retirement, when earnings ceased and savings might be inadequate.

Rowntree's discussion was of absolute poverty, of lacking the means to provide basic food, clothing and housing. But his observations apply equally in today's ethos of relative poverty.

A family unit consisting of husband, wife and children requires a higher disposable income than does a single person, in order to live an abstemious life, a comfortable life, a wealthy life, or an extravagant life. An income which means wealth for a single person will maintain a family in little more than penury. Yet many welfare analysts and polemicists leave this factor entirely out of account in their use of the terms 'wealthy' and 'high income' in the context of family earnings and taxation.

If a mean standard is set based on personal income, lifestyle and appurtenances enjoyed by wage earners without dependents, members of families which include dependent children will always exist in a state of relative poverty unless there is intervention of some kind. This problem cannot be solved by both parents working. To the extent that the mother (or second parent) works, care of the children must be paid for, returning income to absolute or relative poverty levels; or else the children suffer the poverty of neglect, and the parents, poverty of leisure.

The requirement for intervention derives from the fact that the differential income needs of family and single earners do not accord well with the accounting methodology of the wage economy - neither unions nor employers have seriously contemplated adjusting wages to the number of dependents of the wage earner on an individual basis. The question of whether businesses can afford to pay all employees at a level which would maintain the majority of families in comfort (and those without dependents in luxury) is moot, and has never been clearly answered in the affirmative, although Rowntree's observation of an absence of poverty in the period of marriage pre- and post-children suggests that a single wage could, at that time, profitably cover the needs of a couple without children.

If this is the case, what the state can do, and the individual business cannot or will not do, is intervene to redistribute the value of labour from the single to the family earner, such that the wages bill remains the same, but the family receives the benefit of part of the labour of those without dependents. This is surely an impeccable project in collective responsibility and cooperation, and the evidence of the major part of this century is that by this means both families and single people can live comfortably while business remains profitable. A crisis in both family incomes and business viability followed hard on the heels of its progressive abandonment from the mid-1970, and has, to date, proved impervious to alternative strategies promoting employment and family welfare.

The first major intervention to solve the life cycle problem of family disadvantage in Australia functioned at the market level of wages. The Harvester judgment of Justice Higgins in 1907 divided wage earners into categories according to their likelihood of having to support dependents - adult males, junior males, and females (adult and junior). Adult males were likely to be supporting a family and their 'basic wage' was to be adequate for 'a family of about five' living in 'frugal comfort', while wages for junior males and females, who were more likely to be supporting only themselves, or living within a supportive family, were considerably lower.

Higher level wages were built on this structure. Thus government wage fixing engineered the redistribution of work value from the single to the family earner, raising the income of the latter without raising the total wages bill. Neither taxation differentials nor welfare payments, such as we are now familiar with, were employed as media of transference - their historical time had not yet come.

Taxation differentials could not be adopted at that stage simply because for most of the first half of this century no income tax was paid by persons on even quite comfortable incomes. The threshold for income tax in the 1920s was four to six times the basic wage, and in 1940 was still three times the basic wage. But in 1943, with the cost of war, the threshold was reduced to less than double the basic wage, and tax began to eat into average family earnings. A more accurate targeting of the well-off, on a per capita basis, was needed, than the broad category of 'adult male' provided, if revenue was to be increased without recreating life cycle disadvantage.

To allow families with dependent children a degree of prosperity both adequate and commensurate with their child-free socio-economic peers, but without forcing up wages and harming industry, an Australia-wide, universal 'child endowment' was introduced - a flat payment per child of considerable value in relation to minimum earnings at that time. This was initially funded by a new 'payroll' tax, thus emphasising that workforce labour and the wages supplied by industry were still supporting all members of the populace directly - the government was merely passing over some of its value from single earners to families. Thus welfare, or family payments, became a second strategy of redistribution from single or couple to family earners.

In the 1950s, as taxes impinged on ever lower levels of income, and the basic wage fell in relative value (the female rate was raised to 75 per cent in 1950), tax differentials became a third, and interactive, strategy in government amelioration of family income disadvantage. Redistribution of income from single earners to families was engineered by absolving earners with dependents of a large part, or of all, of the standard tax contribution. The level of relief was determined by a system of flat-rate deductions for dependent spouse and children, and variable deductions for expenditure on essential items which increase in cost with number of dependents - medical and educational expenses, house and water rates, life insurance and so on.

This in effect meant that family earners, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the number of their children and their gross incomes, were spared the contribution taxation represents to the running costs of the infrastructure of society from which all benefit (roads, hospitals, police, schools, state pensions and so on), while those without dependents contributed correspondingly more - again, an impeccable collective enterprise.

As the value of child endowment had now atrophied and wage differentials had diminished, it also suggests that the value of one man's annual work came close to providing for the direct needs of a moderate-sized family, but did not cover the indirect costs of social infrastructure which are funded by taxation.

In 1974, equal pay was introduced, and so the redistribution from single earners to families at the wage level (which was increasingly inaccurate on a category basis) was abolished. This meant that if wages were not to destroy profitability, then average wages must eventually fall in value, as what was added for women and young adults must be taken from adult men. This was realised with the fall in the real value of middle incomes in the 1980s.

If families were not to suffer, their net incomes needed more topping up than before, and this must now fall on the two strategies of tax relief and welfare. It is, of course, obvious that reliance on welfare, without employing tax exemption, means that the effectiveness of the operation is greatly diminished, as the income level at which topping up begins is lower than it would be if tax exemptions were also in place.

Unfortunately, just at this point of increased need, the tax-exemption method of redistribution was partially (in the late 1970s) and then wholly (in the early 1980s) removed. First deductions for dependent children, and then for family expenses, were withdrawn, being putatively compensated by an increased flat-rate, universal family payment (a new version of child endowment), which was non-indexed in a period of uniquely high inflation.

These changes were fuelled in part by feminist critique and polemic, but also by a more general anti-family ideology, which perhaps represented the revolt of the single earner against the collective enterprise of family support engineered by government. Collective responsibility for the nation's children was largely abandoned, and by the mid-1980s the family was in shock as the permanence of its sudden absolute and/or relative poverty sank in. Even a yuppie- and grey-powered society could not ignore the reappearance of child poverty, although it continued to avert its eyes from family disadvantage in general. The new individualists could not see their way to parting with more of their new-found wealth than was necessary to repair conditions like those observed by Rowntree, and so, rather than returning to the old system of universal support for the family, which recognised both absolute and relative disadvantage, targeted family payments were introduced for the first time in Australia.

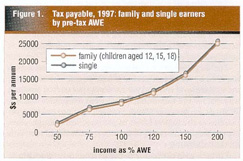

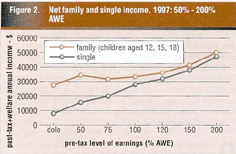

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the means by which this was achieved. Taxation was made virtually equal for family and single incomes, ignoring the much lower spending capacity per person in families on nominally equivalent incomes.

Figure 1: Tax payable, 1997: family and single earners by pre-tax AWE

Figure 2: Net family and single income, 1997: 50% - 200% AWE

The net result of concentrating welfare on those below the poverty line, while affording no tax relief to family earners, is that a large bracket of family incomes is levelled to a single minimum family income. This represents the perfect realisation of welfare's social justice principle that no family should receive tax or other recompense of the extra costs of its several members, if its net income would thereby rise above the current level of welfare benefits for a family of its size and composition. The fact that taxation reduces the majority of families to poverty line or welfare levels of income, while it leaves all earners without dependents well above the single welfare income, is apparently of no moment for social justice.

The targeting of welfare is currently considered to be required by social justice, but if total equality of income at the welfare level is social justice for 80 per cent of families, why not for the remaining 20 per cent of families and for all single earners too? It can be seen that net incomes of families at the higher levels of income, and of single earners across the full range of incomes, continue to rise with increased earnings.

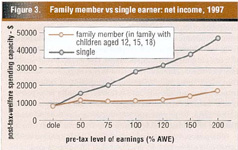

There is also the factor of per person income within the family. Suppose, given the lower costs of children compared with adults, each member of a family of five is regarded as enjoying the value of a third of the family income, proportional to needs, then their financial situation obviously compares poorly with that of a single earner on the same salary (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Family members vs single earner: net income, 1997

If social justice of the kind visited on middle-income families is the ideal, should not that comparative wealth of single earners be sacrificed, via taxation, in order to raise the incomes of family members living at one third that rate, either by decreasing their tax or increasing their family payments.

Practical problems have increasingly emerged as a result of the targeted welfare approach to family relief. Currently attracting attention is the problem of the high effective marginal tax rates generated at the intersect of tapered welfare payments and the band of earned incomes at the welfare threshold. A simple solution, coordinate with social justice, would be to increase the tax rate on all incomes above the welfare threshold to 100 per cent! The fact that this is not suggested indicates that we do not really believe in the equality of income imposed on middle-income families. Equally easily, we could resolve it by returning to universal family rebates, deductions, or payments, which recognise the call on income of raising children at every income level.

The present system of non-differential taxation and targeted welfare has determined that all parents and children will live in relative poverty - that the range of incomes accessible on an individual basis in childhood and parenthood will always describe a far lower gradient than those accessible to the adult and child free. If the state is to strengthen families, it must not just focus on establishing a minimum competence to which the majority are either raised or forced to fall.

Equity for families must embrace equity vis a vis single earners. It is unjust and inaccurate to place family incomes on a scale which does not discriminate in terms of the number of persons supported. The discourse of income must include recognition of its per capita reality, of its sharing among many within the family.

At a conference on taxation held by the Australian Institute of Political Science in 1980, Cass (in Edwards 1980) drew attention to the recurrently demonstrated interrelationship of family allowances and wage fixation, of welfare and the market economy. In 1927, in 1941, in 1976, and later in 1983, whenever universal family allowances were introduced or increased, this was in tandem with a pegging of minimum wage rates. In each case, the pressure for wages to rise across the board to meet specifically family needs was diverted by increasing family income by other means. It was apparently understood that to raise wages for single and family earners alike to a level which would provide adequately for families would be damaging to the economy.

The repeated juggling, across more than half a century, of wages, tax and welfare suggests, indeed, the presence of an 'immutable' law, one which must be accepted prima facie, and accommodated satisfactorily, if erosive pressures on either the family or business are to be avoided - namely, that on average the value of the annual work of one person will cover that person's living expenses together with his share of the cost of the maintenance operations of government which underpin the functioning of advanced societies. But, and this is the crux of the problem, this same average value of the annual work of one adult person will not cover those same expenses for a family.

Rowntree's identification of the problem a century ago is still valid, and we are still dependent on the state to organise a solution, which must entail the collectivist redistribution of some part of the fruits of labour from those without, to those with, dependents. We are currently embracing a theory and policy of social justice which keeps families with dependent children, relative to the rest of society, weak financially, and therefore enfeebled in the tasks of developing the cultural and social manners built upon material welfare.

References

- Edwards, M. (1980), 'Social effects of taxation', in J. Wilkes (ed.) The Politics of Taxation, Hodder & Stoughton, Sydney.

- Rowntree, B.S. (1901), Poverty: A Study of Town Life, Macmillan, London.

Dr Lucy Sullivan is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies, Sydney. She has published widely in academic journals including the British Journal of Sociology, the Journal of Medicine and Law, and the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Her publications for the Centre include Rising Crime in Australia, and State of the Nation (co author). The present paper

This article, an edited version of a paper presented at the Social Policy and Research Centre Conference in July 1999, draws on material from the author's forthcoming monograph, Tax and the Family.