Care-time arrangements after the 2006 reforms

Implications for children and their parents

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

March 2011

Lixia Qu, Rae Kaspiew, Kelly Hand

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

By Ruth Weston, Lixia Qu, Matthew Gray, Rae Kaspiew, Lawrie Moloney, Kelly Hand and the Family Law Evaluation Team

Family Matters Issue 86, 2011, pp. 19-32

The 2006 family law reforms were designed to strengthen family relationships regardless of the parents' relationship status, and to protect and promote children's wellbeing. A key question that arises from the changes is: Under what circumstances are children advantaged or disadvantaged by arrangements that set out or encourage significant amounts of time with both parents? This article therefore examines four issues: the prevalence of different care-time arrangements in families that experienced parental separation after July 2006; parents' views about the flexibility and workability of their arrangements; characteristics of families with different care-time arrangements; and the strength of the relationship between child wellbeing on the one hand, and care-time arrangements and family dynamics on the other. The analysis is based on Wave 1 of a survey of 10,002 parents who participated in the first wave of the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families in 2008.

The 2006 family law reforms were developed in the context of concerns that many children in separated families were losing their opportunity to grow up with the love and support of both their parents.1The reforms were designed, ultimately, to strengthen family relationships regardless of the parents' relationship status, and to protect and promote children's wellbeing by:

- encouraging greater involvement of both parents in their children's lives after parental separation, where this is in the children's best interests;

- helping parents who are unable to otherwise do so to come to an agreement on the nature of arrangements that are best for the children, rather than taking their case to court; and

- placing increased emphasis on protecting the children from family violence, abuse or neglect.

The Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth) (SPR Act 2006) introduced a presumption in favour of parents having equal responsibility for making decisions on issues that have long-term implications for their child's welfare (s61DA) - where there are no reasonable grounds to believe that a child's parent, or someone else in the parent's household, has engaged in child abuse or family violence (s61DA(2)). The legislation specifies that the court must be satisfied that such an order is in the child's best interests (s61DA(4), s60CA). Where parenting orders provide parents with equal shared parental responsibility pursuant to the presumption, then the court must consider making orders that the child spend equal time with both parents, or "substantial and significant" time with them, where this is practicable and in the child's best interests (s65DAA).

Some empirical studies have suggested that, after parental separation, on average, children benefit from being in the care of each parent for substantial periods of time, but others have suggested that care-time arrangements are not related to child wellbeing (see Amato & Gilbreth, 1999; Bauserman, 2002; Kushner, 2009; Gilmore, 2006). A key question, therefore, is: Under what circumstances are children's wellbeing positively or negatively affected by arrangements that entail spending significant amounts of time with both parents? A variety of potentially relevant circumstances have been discussed in the literature; for example, distance between the two homes; inter-parental relationship dynamics, safety issues and a history of family violence, abuse or neglect; how much involvement each parent has had in their children's lives prior to separation; the quality of the parent-child relationship; parenting competence or styles; the flexibility of the arrangements; and age-related developmental needs of the children.

Regarding the latter issue, concerns have been expressed about the appropriateness of shared care time for very young children (e.g., McIntosh & Chisholm, 2008; McIntosh, Smyth, & Kelaher, 2010). Here, shared care time is typically defined as the children spending at least 30-35% of nights with each parent.

A great deal of concern has also been expressed about children experiencing shared care-time arrangements where the relationship between parents is marked by high acrimonious conflict (see Amato, Meyers, & Emery, 2009; Bauserman, 2002; McIntosh, Smyth, Wells, & Long, 2010). Two issues are especially pertinent here. The first relates to the many studies suggesting that children's exposure to high conflict is damaging to their wellbeing (see Amato, 2005; Grych, 2005; Potter, 2010). The second is the suggestion that the more time children spend with each parent, the greater will be their exposure to inter-parental relationship dynamics (e.g., Amato et al., 2009; Bauserman, 2002). This second concern has been more difficult to establish empirically.

In terms of decision-making processes, it seems reasonable to suggest that high levels of acrimonious conflict would be more prevalent among parents who contest their case in court than among parents who come to arrangements between themselves. This will not always be the case; for example, an agreement may arise out of coercion.

The quality of parent-child relationships and parenting styles or competence also appear to be very important factors that shape the impact on child wellbeing of time spent with the non-resident parent. Children need to spend time with a parent in order for high-quality relationships to develop or be maintained but, of course, where this parent has poor parenting skills or is neglectful or abusive towards the child, the experience is very likely to impair the relationship and compromise the child's wellbeing (see Amato & Gilbreth, 1999; Gilmore, 2006; Kushner, 2009).

In addition, a considerable amount of evidence supports the view that, among other factors, arrangements need to be somewhat flexible in order to work well for parents and the children (see Cashmore et al., 2010; McIntosh & Chisholm, 2008; McIntosh, Smyth, Wells, & Long, 2010; Smart, 2004). McIntosh, Smyth, Wells, & Long maintained that inflexible arrangements may be a proxy for underlying problems in the inter-parental relationship. In fact, it seems reasonable to suggest that, at least in some cases, one parent's attempts to impose a rigid regime may primarily reflect a desire to assert control over the life of the other parent and possibly the child(ren). Control of the other, and the sense of entitlement that may motivate this control, appear to be two of the core elements associated with chronic and ongoing family violence (Gilchrist, 2009).

A key problem with interpreting the research findings to date is that, for the most part, different care-time arrangements tend to be adopted by families that differ systematically in some of their characteristics. For instance, there is some evidence that fathers are more likely to have substantial involvement in their children's lives where they and their children's mother have a cooperative relationship (e.g., Cashmore et al., 2010; Sobolewski & King, 2005). However, it is difficult to establish the existence or direction of any causal links between such variables.

This article examines four issues:

- the prevalence of different care-time arrangements in families that experienced parental separation after July 2006;

- parents' views about the flexibility and workability of their arrangements;

- characteristics of families with different care-time arrangements; and

- the strength of the relationship between child wellbeing on the one hand, and care-time arrangements and family dynamics on the other.

The analysis is based on a survey of 10,002 parents who participated in the first wave of the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families conducted in 2008 (LSSF 2008). This survey, which was part of the Australian Institute of Family Studies' (AIFS) evaluation of the 2006 changes to the family law system, took place up to 26 months after parental separation (with the average duration of separation being 15 months). All parents were registered with the Child Support Agency (CSA) in 2007, and attention was directed to the care-time arrangements of the first child listed for each family in the CSA database (here called "the focus child" or "the child"). Most of these children were of preschool age: 41% were less than 3 years old and 18% were 3-4 years old, 29% were 5-11 years old, and 7% and 5% were 12-14 and 15-18 years old respectively. The sample comprised similar proportions of fathers and mothers (see Kaspiew et al., 2009 for detailed information about the survey).2

Consistent with the CSA Child Support liability cut-offs, children with 35-65% of nights in the care of each parent were considered to have "shared care-time arrangements". This set of arrangements was also subdivided as follows:

- 53-65% of nights per year with their mother and 35-47% of nights with their father (shared care time involving more nights with the mother);

- 48-52% of nights per year with each parent (equal care time); and

- 35-47% of nights with their mother and 53-65% of nights with their father (shared care time involving more nights with the father).

In practice, the scheduling of time with each parent is commonly linked with the significance of specific days or periods (weekdays, weekends, school holidays and festive days such as Christmas Day, Father's or Mother's Day, and birthdays). For example, a child who stays overnight with one parent every Friday and Saturday of the year, along with every Sunday for half the weeks in a year, would be classified as having a shared care-time arrangement (i.e., they spent, on average, 2.5 nights every week per year or 35% of nights per year with this parent).

Care-time patterns according to the age of the focus child

Table 1 lists the full set of care-time arrangements examined and shows the proportion of children of different age groups who experienced each, as indicated by the parents.

| Proportion of nights per year with each parent | Groups | Age of child (years) % | All children % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-2 | 3-4 | 5-11 | 12-14 | 15-17 | |||

| Detailed care-time arrangements | |||||||

| Father never sees child | a | 16.2 | 8.4 | 5.3 | 10.6 | 13.0 | 11.1 |

| Father sees child in daytime only | b | 34.4 | 15.5 | 12.0 | 14.0 | 22.6 | 22.5 |

| 87-99% with mother (1-13% with father) | c | 13.8 | 13.9 | 13.7 | 14.3 | 18.3 | 14.1 |

| 66-86% with mother (14-34% with father) | d | 25.4 | 37.1 | 37.2 | 31.1 | 18.7 | 31.0 |

| 53-65% with mother (35-47% with father) | e | 5.0 | 9.3 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 3.3 | 7.8 |

| 48-52% with each parent (i.e., equal care time) | f | 2.1 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 10.7 | 6.4 | 7.0 |

| 35-47% with mother (53-65% with father) | g | 0.4 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| 14-34% with mother (66-86% with father) | h | 0.8 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 1.9 |

| 1-13% with mother (87-99% with father) | i | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 1.1 |

| Mother sees child in daytime only | j | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 1.3 |

| Mother never sees child | k | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 1.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| No. of observations | 2,684 | 1,309 | 2,538 | 627 | 560 | 7,718 | |

| Selected combined care-time groups | |||||||

| 100% of nights with mother | a + b | 50.6 | 23.9 | 17.3 | 24.6 | 35.6 | 33.6 |

| Most nights with mother | c + d | 39.2 | 51.0 | 50.9 | 45.4 | 37.0 | 45.1 |

| Shared care time (35-65%) | e + f + g | 7.5 | 20.3 | 25.7 | 20.2 | 10.8 | 16.1 |

| Most nights with father | h + i | 1.3 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 5.8 | 7.9 | 3.0 |

| 100% nights with father | j + k | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 8.7 | 2.3 |

| Father or mother never sees child | a + k | 16.6 | 9.4 | 6.2 | 13.1 | 17.3 | 12.1 |

Notes: Based on analysis of focus child's care-time arrangements. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Source: LSSF 2008

One-third of the children never stayed overnight with their father, with 11% never seeing their father, and 23% seeing their father during the daytime only. Conversely, only 2% of children never stayed overnight with their mother, with 1% never seeing their mother and the other 1% seeing their mother during the daytime only.

Around 45% of children stayed overnight with their mother most nights; that is, 66-99% of nights (with most of these children being in the care of their mother for 66-86% of nights, and in the care of their father for 14-34% of nights). Almost 79% of the children spent most or all nights with their mother and only 5% of children spent most or all nights with their father.

Overall, 16% of children experienced a shared care-time arrangement, and similar proportions of children (7-8%) had either equal care time or shared care time involving more nights with their mother. Only 1% of all the children experienced shared care time involving more nights with their father than mother.

The prevalence of the different care-time arrangements varied considerably according to the child's age. Although most children in all age groups spent more time with their mother than their father, shared care time was most commonly experienced by children aged 5-11 years (26% compared to 8-20% for other age groups), and the proportion who spent most or all nights with their father increased progressively with age (from 3% of those aged under 3 years to 17% of those aged 15-17 years).

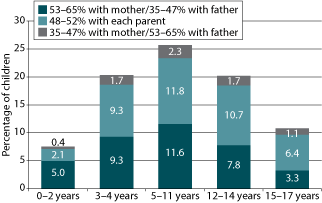

Figure 1 shows that shared care time in general was unusual for children less than 3 years old (applying to 8% of these children). Children aged 3-4 years were nearly three times as likely as those less than 3 years old to experience shared care time (20%), while children aged 5-11 years were the most likely of all age groups to experience this arrangement (26%). Thereafter, shared care time declined progressively with age, applying to 20% of all children aged 12-14 years, and 11% who were 15-17 years old - a trend that appears to result mainly but not entirely from the increasing proportion of teenage children who, as they mature, spend most or all nights with their father.

Figure 1: Shared care-time arrangements, by age of child, 2008

Source: LSSF 2008

The experience of equal care time, rather than unequal but still shared time, also varied according to children's ages. No more than 2% of children in each age group experienced shared care-time arrangements involving more nights with their father than their mother, whereas among the small proportion of children less than 3 years old in shared care-time arrangements, two in three spent more nights with their mother than their father. Children aged 3-4 years and 5-11 years with shared care-time arrangements were just as likely to experience equal care time as to experience shared care time involving more nights with their mother than their father.

In general, the pattern of age-related results for children who never saw one parent is the reverse of that outlined above for children with shared care-time arrangements (Table 1). The youngest and oldest groups were the most likely to never see one parent (16% and 12% respectively), with this parent being far more likely to be the father than the mother. The proportion of children who never saw one parent decreased with increasing age until age 5-11 years (applying to 6% in this age group), then increased progressively with age.

Parents' evaluations of their arrangements

In order to simplify the analysis outlined in this section, the following care-time arrangements listed in the top panel of Table 1 were combined: (a) where the child was in the care of the mother for either 66-86% or 87-99% of nights; and (b) where the child was in the care of the father for these two different percentages of nights. This yielded nine different arrangements. However, when the reports of fathers and mothers were considered separately, only 29 mothers indicated that they never saw their child and only 38 said that they had a shared care-time arrangement involving the child spending more nights with the father than with them; therefore, statistics were not derived for these two groups of mothers.3

Perceived flexibility of the arrangements

Parents in the LSSF were asked whether their parenting arrangements were "very flexible", "somewhat flexible", "somewhat inflexible" or "very inflexible".4 The majority of parents in all except one group indicated that their arrangements were somewhat or very flexible. Fathers who never saw their child were the exception, with two-thirds of these fathers describing their arrangements as "very inflexible". However, perceptions of flexibility varied with the nature of the care-time arrangement, and the respondent's own level of care time and gender.

Parents with the majority of care time were more likely than those with the minority of care time to believe that arrangements were flexible. For example, where the father saw the child during the daytime only, 65% of fathers and 81% of mothers described the arrangements as "very" or "somewhat" flexible. Among parents with shared care time, fathers were more likely than mothers to believe that arrangements were flexible (80-82% vs 71-75%). The parents who were most likely to describe their arrangements as flexible were fathers with shared care time and those who cared for their child most nights (80-82% vs 31-76% of other fathers), and mothers who cared for their child most nights and those whose child saw the father during the daytime only (81% vs 56-75% of other mothers).

Perceptions about the workability of the arrangements

Parents were asked to indicate how well their arrangements were working for themselves, their child and their child's other parent. The response options were "really well", "fairly well", "not so well" and "badly". The following analysis focuses on the proportions of fathers and mothers with each care-time arrangement who considered that their arrangements were working well (i.e., "really well" or "fairly well"): (a) for father, mother and child (taken separately); (b) for each party combined (e.g., worked well for all three parties; worked well for mother and child but not father); and (c) for the child, according to his or her age. Around 28% of all parents expressed uncertainty about how well the arrangements were working for at least one of the three parties (most commonly, the child's other parent).

Workability for father, mother and child, taken separately

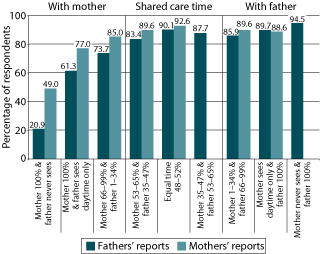

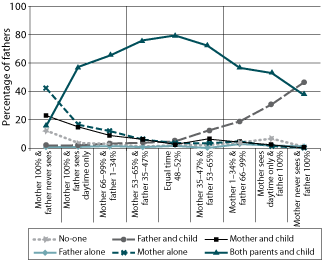

Figure 2 shows that parenting arrangements were most likely to be seen as working well for the father where the child experienced shared care time or spent most or all nights with him. The greater the number of nights that the child spent with the mother compared with the father, the less likely were parents to see the arrangements as working well for the father. The gender difference in evaluations was apparent for the care-time arrangements where the child spent the majority of or all the nights with the mother, with fathers being less likely than mothers to see the arrangements as working well for the father.

Figure 2: Reports by fathers and mothers that the current parenting arrangements were working "really well" or "fairly well" for the father

Source: LSSF 2008

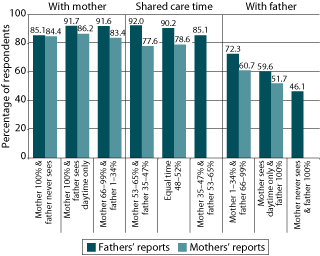

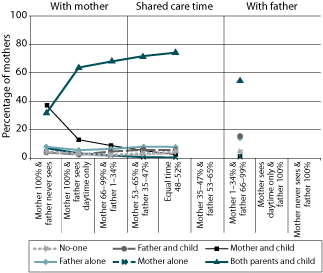

Figure 3 shows that the greater the number of nights that children spent with fathers relative to mothers, the less likely were mothers to report that the arrangements were working well for them. This trend was also apparent from fathers' perspectives where their care time increased beyond equal time. For most care-time arrangements, fathers were more likely than mothers to believe that the arrangements were working well for the mother. Although most parents with shared care time believed that the arrangements were working well for them, the fathers were more likely than the mothers to believe that these arrangements were working well for the mother.

Figure 3: Reports by fathers and mothers that the current parenting arrangements were working "really well" or "fairly well" for the mother

Source: LSSF 2008

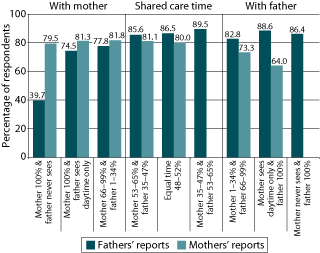

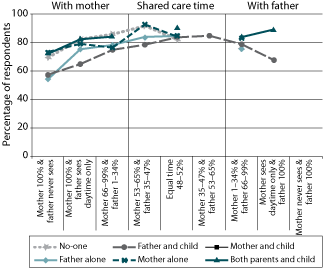

Parents with shared or greater care time were more likely than those with minority or no care time to believe the arrangements were working well for their child (Figure 4). Fathers who never saw their child and mothers who saw their child in the daytime only were the least likely to provide a favourable assessment (especially the former group).

Figure 4: Reports by fathers and mothers that the current parenting arrangements were working "really well" or "fairly well" for the child

Source: LSSF 2008

Workability for father, mother and child, taken together

As noted above, more than one-quarter of parents expressed uncertainty about how well the arrangements were working for one of the three parties. In addition, few indicated that the arrangements worked well for their child alone (< 5%) or for both parents but not their child (10%). Figures 5 and 6 show the proportions of fathers and mothers (respectively) who provided each of the other six possible combinations of answers, according to their care-time arrangement. The following trends emerged:

- Most parents in all groups except those whose child never saw one parent believed that their parenting arrangements were working well for all three parties.

- Parents with shared care-time arrangements were the most likely of all groups to believe that their arrangements were working well for all parties (70-80%). This view became less prevalent as care time was less equally shared.

- Fathers who never saw their child most commonly indicated that their parenting arrangements were not working well for them or for their child, but were working well for the mother.

- Mothers whose child never saw the father, on the other hand, most commonly believed that the arrangements were working well for their child, although they agreed with the fathers that the arrangements were working well for the mother but not the father.

- Likewise, fathers whose child never saw the mother also tended to believe that the arrangements were working well for their child. In addition, they generally considered that the arrangements were working well for them but not for the mother.

Figure 5: Fathers' views on whether the parenting arrangements were working well for them, the mother, and the child

Note: Results for three care-time groups are not shown due to small numbers.

Source: LSSF 2008

Figure 6: Mothers' views on whether the parenting arrangements were working well for them, the mother, and the child

Note: Results for three care-time groups are not shown due to small numbers.

Source: LSSF 2008

Workability of parenting arrangements according to the age of the child

Given concerns about the suitability of care-time arrangements for children less than 3 years old, the proportion of parents (fathers and mothers combined) in each care-time group who indicated that the arrangements were working well for the child were derived according to age of the child (Figure 7).5

More than half the parents in each group provided favourable assessments. Among parents with a shared care-time arrangement involving more nights with the mother than the father, 92-93% whose child was less than 3 years old or 12-14 years old believed that the arrangements were working well for their child. Across all age groups of children, such favourable assessments were provided by more than 80% of parents with equal care time (and were provided by 90% of parents with equal care time whose child was 15-17 years old).6 Parents with a child aged 3-4 years or 5-11 years who never saw his or her father were the least likely to believe that the arrangements were working well for the child (reported by 54-57% of these parents).

Figure 7: Reports by fathers and mothers (combined) that their arrangements worked "really well" or "fairly well" for their child, by age of child

Note: Results for some groups are not shown due to small numbers.

Source: LSSF 2008

Circumstances of families with different care-time arrangements

To what extent do circumstances of the families themselves suggest that the arrangements in place are in the child's best interests? Tables 2 and 3 show, among other issues, the proportions of fathers and mothers who indicated that: (a) they lived close to, or very distant from, the other parent; (b) the other parent had been very involved in their child's life before they separated; (c) their current relationship with the other parent was either friendly or cooperative, or highly conflictual or fearful;7 (d) there had been a history of family violence (physical or emotional), or of physical violence alone; and (e) they held safety concerns (for them or their child) arising from ongoing contact with the other parent.8 These issues seem relevant considerations when making decisions about achieving arrangements that are in the child's best interests.

| Mother 100% & father never sees | Mother 100% & father daytime only | Mother 66-99% & father 1-34% | Mother 53-65% & father 35-47% | Equal time 48-52% | Mother 35-47% & father 53-65% | Mother 1-34% & father 66-99% | Mother daytime only & father 100% | Mother never sees & father 100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median annual personal income ($) | 35,000 | 40,000 | 49,000 | 50,000 | 52,000 | 45,000 | 35,000 | 30,000 | 35,000 |

| Educational attainment | |||||||||

| Degree or higher qualification (%) | 7.3 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 15.7 | 19.4 | 16.1 | 11.6 | 6.4 | 4.6 |

| Year 11 or lower (no post-school qualification) (%) | 39.1 | 34.7 | 31.1 | 23.9 | 20.5 | 28.8 | 36.6 | 43.8 | 53.4 |

| Relationship status at separation | |||||||||

| Married to other parent (%) | 38.7 | 36.5 | 56.6 | 58.4 | 71.8 | 59.1 | 54.9 | 58.7 | 51.5 |

| Never married to mother nor living with mother when child was born (%) | 20.6 | 24.2 | 9.7 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 6.8 |

| Other parent was "very involved" in child's day-to-day activities before separation (%) | 73.4 | 83.2 | 78.3 | 71.1 | 62.0 | 46.8 | 41.7 | 37.0 | 29.5 |

| Distance between the two homes | |||||||||

| Less than 10 km/15 minutes (%) | 18.6 | 32.7 | 35.8 | 51.5 | 56.6 | 51.9 | 36.5 | 35.1 | 14 |

| 500+ km/6+ hrs (%) | 29.5 | 8.7 | 7.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 29.8 |

| Experienced family violence before/during separation | |||||||||

| Physical hurt or emotional abuse (%) | 69.8 | 44.1 | 50.0 | 57.7 | 56.4 | 60.7 | 61.5 | 73.9 | 74.1 |

| Physical hurt before separation (%) | 26.5 | 12.1 | 14.9 | 17.9 | 15.5 | 22.9 | 23.5 | 33.4 | 25.1 |

| Holds safety concerns linked with ongoing contact a (%) | 37.8 | 11.9 | 12.8 | 16.2 | 17.9 | 20.0 | 23.8 | 24.8 | 36.3 |

| Current quality of relationship with other parent | |||||||||

| Friendly/cooperative (%) | 24.0 | 67.3 | 68.9 | 68.8 | 64.7 | 67.1 | 58.4 | 53.5 | 30.8 |

| Highly conflictual/fearful (%) | 43.3 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 13.2 | 14.7 | 11.8 | 16.2 | 24.9 | 30.0 |

| Had sorted out parenting arrangements (%) | 29.5 | 62.2 | 76.5 | 81.4 | 86.4 | 84.7 | 79.0 | 67.9 | 59.7 |

| Main pathway for reaching parenting arrangements b | |||||||||

| Just happened (%) | 28.3 | 17.1 | 10.6 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 14.8 | 22.5 | 42.1 |

| Discussions with other parent (%) | 48.3 | 69.6 | 73.5 | 66.9 | 67.5 | 69.9 | 65.2 | 41.8 | 26.6 |

| Counselling, FDR etc./lawyers/courts (%) | 20.2 | 11.1 | 14.2 | 22.0 | 24.1 | 24.2 | 15.1 | 30.1 | 23.7 |

Notes: For each variable, the differences across care-time groups are statistically significant (p < .05). Data have been weighted. a Safety concerns related to child and/or respondent. b Percentages for "main pathway" are based on those who had sorted out their arrangements.

Source: LSSF 2008

| Mother 100% & father never sees | Mother 100% & father daytime only | Mother 66-99% & father 1-34% | Mother 53-65% & father 35-47% | Equal time 48-52% | Mother 35-47% & father 53-65% | Mother 1-34% & father 66-99% | Mother daytime only & father 100% | Mother never sees & father 100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median annual personal income ($) | 25,000 | 24,002 | 27,002 | 31,306 | 33,915 | * | 26,089 | 23,480 | * |

| Educational attainment | |||||||||

| Degree or higher qualification (%) | 9.3 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 21.1 | 22.2 | * | 10.6 | 4.3 | * |

| Year 11 or lower (no post-school qualification) (%) | 40.8 | 35.4 | 30.3 | 25.0 | 25.6 | * | 45.3 | 35.7 | * |

| Relationship status at separation | |||||||||

| Married to other parent (%) | 34.7 | 35.8 | 54.9 | 63.2 | 76.5 | * | 59.4 | 61.9 | * |

| Never married to mother nor living with mother when child was born (%) | 27.4 | 25.9 | 9.3 | 2.8 | 2.0 | * | 5.6 | 9.0 | * |

| Other parent was "very involved" in child's day-to-day activities before separation (%) | 9.8 | 16.4 | 16.1 | 20.7 | 21.5 | * | 32.4 | 36.6 | * |

| Distance between the two homes | |||||||||

| Fewer than 10 km/15 minutes (%) | 21.5 | 35.3 | 37.5 | 54.6 | 54.6 | * | 35 | 47.4 | * |

| 500+ km/6+ hrs (%) | 24.1 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | * | 10.1 | 1.7 | * |

| Experienced family violence before/during separation | |||||||||

| Physical hurt or emotional abuse (%) | 74.7 | 58.4 | 63.6 | 70.4 | 69.5 | * | 71.8 | 79.0 | * |

| Physical hurt before separation (%) | 39.9 | 20.9 | 23.5 | 24.5 | 23.5 | * | 36.7 | 28.0 | * |

| Holds safety concerns linked with ongoing contact a (%) | 37.5 | 19.7 | 18.6 | 19.4 | 16.0 | * | 24.1 | 25.3 | * |

| Current quality of relationship with other parent | |||||||||

| Friendly/cooperative (%) | 25.8 | 70.6 | 67.3 | 57.7 | 61.0 | * | 57.4 | 48.4 | * |

| Highly conflictual/fearful (%) | 38.2 | 15.1 | 16.0 | 24.1 | 22.3 | * | 21.0 | 25.4 | * |

| Had sorted out parenting arrangements (%) | 51.1 | 72.8 | 79.0 | 78.0 | 84.4 | * | 70.9 | 64.7 | * |

| Main pathway for reaching parenting arrangements b | |||||||||

| Just happened (%) | 42.7 | 27.4 | 12.7 | 6.1 | 4.9 | * | 16.3 | * | * |

| Discussions with other parent (%) | 33.7 | 62.9 | 69.3 | 57.8 | 61.4 | * | 58.8 | * | * |

| Counselling, FDR etc./lawyers/courts (%) | 17.5 | 7.5 | 15.4 | 32.0 | 29.6 | * | 18.6 | * | * |

Notes: For each variable, the differences across care-time groups are statistically significant (p < .05). Data have been weighted. * Percentages were not derived because there were fewer than 40 mothers represented in these groups. a Safety concerns related to child and/or respondent. b Percentages for "main pathway" are based on those who had sorted out their arrangement.

Source: LSSF 2008

Other issues listed in Table 2 focus on: (a) socio-economic status indicators for the respondent (personal income and educational attainment); (b) the parents' relationship status at the time of separation or the child's birth; and (c) whether the parenting arrangements had been sorted out, and if so, the main pathway taken for doing so.

Taken together, these results suggest that the profiles of families with different care-time arrangements differed in several respects.

Where the child experienced shared care time

Fathers were twice as likely as mothers to indicate that they had a shared care-time arrangement (22% vs 12%). On average, these parents tended to have higher socio-economic status, as measured by their educational attainment and incomes, and those with equal care time were also considerably more likely than all other groups to have been married to the child's other parent. Not surprisingly, they were the most likely of all groups to report that they lived less than 10 km or a 15-minute drive from the other parent (52-57% of fathers and 55% of mothers). Almost all the others lived within 50 km or a one-hour drive (data not shown).

Based on the reports of respondents about their child's other parent, parents with shared care-time arrangements were more likely to have been "very involved" in their child's day-to-day life before separation than were those with a minority of care nights or no care nights.9 This pattern of results for parents with shared care time, compared with parents with a minority of care nights, is consistent with the intent of the reformed Act, which, under section 60B(1), aimed to ensure "that children have the benefit of both of their parents having a meaningful involvement in their lives" and which, under section 60CC(2), supported "the benefit to the child of having a meaningful relationship with both of the child's parents".

While the majority of respondents in most groups described their inter-parental relationship as either friendly or cooperative, parents with a shared care-time arrangement were among those most likely to report such positive relationships. Nevertheless, the mothers with these arrangements were less likely to report positive relationships than mothers who cared for their child most nights and those whose child saw the father during the daytime only (especially the latter group). In fact, 22-24% of mothers and 12-15% of fathers with shared care-time arrangements described the relationship as being highly conflictual or fearful.

Although parents with shared care time were among the least likely to express concerns about their own or their child's safety linked with ongoing contact with the other parent, a substantial minority did so (16-20%). Furthermore, approximately one-quarter of mothers and 16-23% of fathers indicated that they had been physically hurt prior to separation, and fathers and mothers with a shared care-time arrangement were more likely to indicate that they had experienced some form of family violence prior to separation than parents whose child was in the care of the mother for 66-99% of nights and those whose child saw the father during the daytime only.

While most parents in most care-time groups believed that they had sorted out their parenting arrangements, those with shared care time (and mothers with 66-99% of care nights) were the most likely to report this (81-86% of fathers and 78-84% of mothers). As for most of the other groups, these parents most commonly indicated that they had arrived at their arrangements mainly through discussions with the other parent (67-70% of fathers and 58-61% of mothers) and they were the least likely to state that the arrangements had "just happened" (6-10% of fathers and 5-6% of mothers). Although applying to a minority, these parents were among the most likely of all groups to have used some form of formal assistance in sorting out their parenting arrangements.

Where the child never saw the father

Approximately 8% of fathers and 13% of mothers indicated that their child never saw the father. Along with those whose child saw his or her father during the daytime only, parents whose child never saw the father were the youngest of all groups, the least likely to have been married to the child's other parent and the most likely to have either never lived with the other parent or to have separated before their child was born. Their child was in most cases less than 3 years old at the time of the survey. According to respondents' reports about the other parent, most mothers and few fathers whose child never saw the father had been very involved in the child's everyday activities before separation.

Parents whose child never saw the father were also among those least likely to have post-school qualifications and the median personal income of the fathers was among the lowest, while that for mothers fell between the levels derived for other female groups. Together with those whose child never saw the mother, these parents were the least likely to live within 10 km of each other and a substantial minority lived 500 km, or more than six hours' drive, from the child's other parent.

Both the mothers and fathers in this group were inclined to report that their relationship with their child's father was either conflictual or fearful rather than friendly or cooperative. In addition, they were among those who were most likely to report that their partner had physically hurt them prior to separation and to express safety concerns linked with any ongoing contact with the other parent.10

Whereas most parents believed that they had sorted out their parenting arrangements, fewer than one-third of fathers in this group and only half the mothers held this view. Of respondents who said they had sorted out their arrangements, these fathers and mothers were considerably more likely than most groups to report that the arrangements "just happened".11

Where the child saw the father during the daytime only

Approximately 17% of fathers and 26% of mothers said that the child saw his or her father during the daytime only. Like the parents whose child never saw the father, these parents tended to be relatively young and to have not been living with the other parent when the child was born. This child was most likely to be less than 3 years old at the time of the survey. The parents appeared to be of a slightly higher socio-economic status than those whose child never saw the father, as measured by their educational attainment and median personal income, but they were not as well off as some of the other groups. However, they were considerably more likely than those whose child never saw the father to live within 10 km of the other parent or within a 15-minute drive, and most lived within 20 km or up to a 30-minute drive (data not shown).

Regarding pre-separation parental involvement, mothers' reports suggested that fathers with daytime-only care time were just as likely to have been very involved in their child's life as fathers who cared for their child for a minority of nights, but less likely to have been very involved than fathers who cared for their child most or all nights. The fathers' reports suggested that most mothers whose child saw the father during the daytime only were very involved prior to separation.

Unlike parents whose child never saw his or her father, both fathers and mothers whose child saw the father during the daytime only believed that their relationship with the other parent was friendly or cooperative and these parents were among the least likely of all groups to consider the relationship to be highly conflictual or fearful. On the whole, parents in this group were no more likely than most of the others of the same gender to report safety issues or a history of family violence. Finally, while most parents in this group believed that they had sorted out their parenting arrangements, the mothers were more likely than the fathers to report this.

Where the child spent most or all nights with the father

Only 7% of fathers and 3% of mothers indicated that their child spent most or all nights with his or her father (i.e., 66-100% of nights). The parents with these arrangements tended to be among the oldest, and although their child was typically less than 12 years old at the time of the survey, teenage focus children were more commonly represented in these families than in others.

These parents were among those who were most likely to have left school before completing Year 12, have not obtained any post-school qualification and have low incomes. A substantial minority of the mothers indicated that they were living with at least one full sibling of their focus child (25-29%, data not shown in Tables 2 and 3); that is, the focus child lived mostly or entirely with the father, while at least one of the child's full siblings lived with the mother. (It is important to note that all female respondents represented in this group either cared for their child for 1-34% of nights or during the daytime.)

Between one-third and nearly one-half of those whose child spent daytimes only, or a minority of nights, with the mother lived a short distance from the other parent (within 10 km or a 15-minute drive) - a situation that applied to only 14% of fathers whose child never saw the mother. Approximately 30% of fathers in the latter group indicated that the mother lived at least 500 km or a 6-hour drive away. This is the same proportion as that of fathers who indicated that they never saw their child.

Respondents' reports about the other parent suggested that fathers with most or all care nights were more likely than other fathers to have been very involved in their child's everyday activities prior to separation, while the opposite was the case for mothers; that is, the mothers in such care-time arrangements were considerably less likely than other mothers to have been very involved in their child's everyday activities prior to separation.

Where the child never stayed overnight with his or her mother, the inter-parental relationship appeared to be poor relative to most other groups. Rates of safety concerns (for the respondent or child) relating to ongoing contact with the other parent were relatively high, especially among fathers whose child never saw the mother.12 These parents were also among the most likely to indicate that their child's other parent had physically hurt them prior to separation.

Unlike fathers who never saw their child, most fathers whose child never saw the mother believed that they had sorted out their parenting arrangements, although they were less likely than several other groups of fathers to believe this. The same applied to parents whose child saw his or her mother during the daytime only.

Among those who had sorted out their arrangements, the two groups of fathers with 100% of care nights were more inclined than most male groups to indicate that they had used formal help (family relationship services, lawyers or the courts) to assist with this endeavour. In fact, across all groups of fathers, the proportion of fathers who reported that they mainly used a court to sort out their arrangements was highest among fathers whose child saw the mother during the daytime only (12% vs 2-9%, data not shown). Nevertheless, only a small minority of parents indicated that they had mainly sorted out their arrangements via use of a court.

Implications for children's wellbeing

A central issue behind investigations of care-time patterns, and family diversity more generally, concerns the implications they have for the wellbeing of children. The family law reforms, after all, were aimed at protecting children and promoting their wellbeing.

Parents' were asked to assess different aspects of their child's wellbeing. Most of the questions that were asked varied according to whether the child was aged less than 4 years or at least 4 years, but in general they covered overall health, learning, getting along with other children, general progress, and behavioural and emotional problems.13

The analysis compared assessments of the child's wellbeing made by parents with the most common arrangement (where the child spent 66-99% of nights with the mother and 1-34% of nights with the father) - here called the "reference group" - with the assessments provided by the following groups: (a) parents whose child never saw the father; (b) those whose child was with the father in the daytime only; (c) those with shared care time involving more nights with the mother than the father; (d) those with equal care time; and (e) those whose child spent 53-100% of nights with the father. The last group includes the small subsample whose child had a shared care-time arrangement involving more nights with the father than mother.

For the most part, child wellbeing did not vary significantly with care-time arrangements, once some of the differences in a selection of other circumstances of families were controlled.14There were three exceptions to this general rule. Compared with the reference group:

- fathers who never saw their child provided less favourable assessments on three measures (learning, conduct problems and emotional symptoms);

- fathers with a shared care-time arrangement provided more favourable assessments on three measures (general health, learning and overall progress); and

- mothers whose child spent most or all nights with the father tended to view their child's wellbeing less favourably on four measures (general health, peer relationships, overall progress and conduct problems).

Of course, those who never saw their child would have been less informed than other parents about their child's wellbeing, and parents' evaluations may have been coloured to some extent by their level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their arrangements.

Across all care-time arrangements, children's wellbeing appeared to have been compromised where there had been a history of family violence, where parents held safety concerns (for them or their child) associated with ongoing contact with the other parent, and where the inter-parental relationship was either highly conflictual or fearful. Children in shared care-time arrangements appeared to be no worse off than other children where there had been a history of family violence or a negative inter-parental relationship. However, mothers' assessments suggested that, where there were safety concerns, children in shared care fared worse than those who lived mostly with their mother.15

These findings are consistent with those of Cashmore et al. (2010), who concluded that shared care time tends to work well for the parents who choose it and for their children, although this is not always the case. Importantly, the generally positive findings about shared care time related more to the characteristics of families that chose these arrangements than to the nature of the arrangement. On the basis of two separate studies, McIntosh, Smyth, Kelaher, Wells, and Long (2010) also concluded that the workability of shared care time depended on the circumstances and characteristics of the families that adopt this arrangement. One set of analysis conducted by McIntosh and 16 used data covering four time points from an intervention study of 169 families participating in child-focused mediation and child-inclusive mediation.17 The second set of analysis used data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) in order to compare links between post-separation care-time arrangements and the wellbeing of children aged less than 2 years old, 2-3 years old, and 4-5 years old.18

These authors noted that, compared with other children under the age of 2 years old who had a parent living elsewhere, those of this age who spent one or more nights a week with the non-resident parent exhibited signs of irritability and wariness about separation from their primary caregiver. Furthermore, children aged 2-3 years old who experienced a shared care-time arrangement (defined as five nights or more per fortnight) exhibited signs of considerable distress, but this was not apparent for those aged 4-5 years old. The authors related these different outcomes to the developmental stages of infants and children of 4-5 years old. However, as they noted, their analysis was based on a small number of children, given that shared care-time arrangements are particularly unusual for very young children. The extent to which we can place confidence in these results can only be known with further studies on these matters based on difference samples.

Summary and conclusions

This large-scale, national study of parents who had separated after the 2006 family law reforms were introduced suggests that traditional care-time arrangements, involving more nights with the mother than father, remain the most common some 15 months after separation. In fact, approximately 80% of the children spent 66-100% of nights with the mother, with one-third spending all nights with her. In interpreting the significance of these findings, it is important to note that most children in the study were less than 5 years old.

Of the children who never stayed overnight with their father, two-thirds saw their father during the daytime and the other one-third did not see him at all, and of the three shared care-time arrangements examined - more nights with mother, equal care time, and more nights with father - the last of these was by far the least common.

Equal care-time arrangements were most common for children aged 5-11 years and 12-14 years, followed by those aged 3-4 years, then children aged 15-17 years; that is, children under 3 years old were the least likely to experience such arrangements. Nevertheless, across all age groups, equal care time was considerably less common than some of the other circumstances, including those in which the child never saw his or her father.

Fathers with shared care time (whether equal or unequal) were more likely than the mothers with these arrangements to maintain that their parenting arrangements were flexible, while, among other parents, this view was more likely to be held by those with the majority of care time than those with the minority of care time.

Three sets of analysis were conducted regarding fathers' and mothers' views about the workability of arrangements for themselves, their child and the other parent. The first set focused on how well the arrangements were working for each party separately, while the second focused on how well they were working for all three parties taken together. The third set focused on the workability of arrangements for children of different ages. Here, the reports of respondents (fathers and mothers combined) with each care-time arrangement were compared, according to the age of their child.

The first set of analysis showed that parents with the majority of care time were more likely than those with the minority of care time to believe that the arrangements were working well for them, with the greatest differences being apparent for those whose child never saw the father. Fathers with shared care time were more likely than their female counterparts to believe that their arrangements were working well for them, and a similar though less marked trend emerged in relation to views about how well the arrangements were working for the child. Among respondents who provided an assessment of the workability of arrangements for their child's other parent, those with the most care time were the least likely to see the arrangements as working well for the other parent.

The second set of analysis showed that most fathers and mothers in all groups, except those whose child never saw one parent, believed that the arrangements were working for all three parties, with those with shared care time being the most likely to believe this. These views became less prevalent as care time was less equally shared.

Finally, across all the age groups of children, most parents believed that their arrangements were working for their child. Few of the children under 3 years old spent more nights with the father than mother, and where these children experienced a shared care-time arrangement, they were more likely to spend more nights with the mother (i.e., 53-65% of nights with the mother and 35-47% with the father) than to have an equal care-time arrangement. Nevertheless, among parents of such young children with these two categories of shared care time, the vast majority said that their arrangements were working well for their child.

Families with different care-time arrangements varied considerably across a range of circumstances. For example, there was a close link between post-separation care-time arrangements and respondents' reports about the other parent's level of involvement in the child's everyday activities prior to separation. From this perspective, post-separation care time increased with increases in pre-separation involvement.

While there were clear socio-demographic similarities between parents whose child never saw the father or saw him during the daytime only (e.g., they tended to be relatively young and were less likely than others to have been living with the child's other parent when the child was born), they differed on several dimensions. For example, those whose child never saw the father tended to live further away from the other parent and to have a more problematic relationship with this parent.

Respondents with a shared care-time arrangement tended to have relatively high socio-economic status, and to live fairly close to the other parent. While most parents with shared care-time arrangements reported friendly or cooperative relationships in some areas, they were more inclined to report problematic family dynamics compared with parents whose child spent a minority of nights with the father or saw him during the daytime only (especially the latter group).

For the most part, pre-separation experiences of violence and current safety concerns associated with ongoing contact with the other parent were more commonly reported by parents whose child never saw the father or had limited or no time with the mother than by other groups of parents. Although this is consistent with the aim of the family law system to protect children's wellbeing, there was also evidence that there were some children in shared care-time arrangements who had a family history entailing violence and a parent concerned about the child's safety, and who were exposed to dysfunctional inter-parental relationships. This finding is inconsistent with the aims of the reforms.

Parents assessed their child's wellbeing across several dimensions, covering general health, learning or education, and social, emotional and behavioural adjustment. Assessments of the wellbeing of children in the largest group (those living with their mother for 66-99% of nights) were compared with those provided for children with other care-time arrangements. Here, the children who spent 53-100% of nights with the father were combined into a single group.

Children with shared care-time arrangements appeared to fare as well as (or perhaps marginally better than) children who spent most nights with their mother, while children who never saw their father appeared to fare worse than this reference group. While a history of family violence and highly conflictual inter-parental relationships appeared to be quite damaging for children, there was no evidence to suggest that this negative effect was any greater for children with shared care time than for children with other care-time arrangements. It remains possible, however, that the measures adopted in this analysis were insufficiently sensitive to detect existing effects in these areas.

Safety concerns relating to ongoing contact also appeared to be detrimental to children's wellbeing. Furthermore, this effect appeared to be more marked, according to mothers' reports, for children in shared care-time arrangements than for those who were in the care of their mother most of the time. These findings are consistent with those of Cashmore et al. (2010). Although caution needs to be exercised in inferring causal connections based on cross-sectional data, the results are consistent with the notion that the circumstances that lead to mothers' safety concerns are more detrimental to children with shared care-time arrangements than to those who are in the care of the mother for most of the time.

To date, shared care time appears to be mostly, but by no means entirely, adopted by families for whom such arrangements work well. A concern is that increasing proportions of separated parents for whom it will not work well may also adopt this approach. The extent to which shared care time has changed over the years will be examined in a forthcoming issue of Family Matters.

Endnotes

1 In his second reading of the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Bill 2005, the then Attorney-General, the Hon. Philip Ruddock, stated: "With these reforms to the law and the new family law system, the government wants to make sure as many children as possible grow up in a safe environment, without conflict and with the love and support of both parents" (p. 10).

2 There were around 1,800 focus children whose mother and father both participated in the first wave of the LSSF and provided details about their child's care-time arrangements. To prevent children who had both parents participating in the survey being counted twice in the analysis, data provided by one of these parents were randomly removed when the analysis focused on the child. When the analysis focused on the parent, the data provided by both parents were included.

3 All except one of the groups retained in this analysis comprised at least 100 members. In fact, there were more than 2,000 fathers and mothers (taken separately) whose child was in the care of the mother for 66-99% of nights. The smallest group that was retained consisted of mothers who saw their child during the daytime only (n = 49).

4 The questions about flexibility and workability of parenting arrangements were asked immediately after the nature of care-time arrangements was ascertained. It is thus very likely that parents focused exclusively on their care-time arrangements when answering these questions. Given time constraints, the meanings of "flexibility" and "workability", and the extent to which flexibility was influenced by the needs of the child, were not ascertained.

5 The following proportions of parents were not able to provide an assessment of how well the parenting arrangement worked for the child: 11-15% of respondents whose child never saw one parent and 1-6% of parents with other care-time arrangements. Excluded from Figure 7 are care-time arrangements when estimated by the age of the focus child for which there were fewer than 40 respondents.

6 Owing to the small number of cases, percentages were not derived regarding the assessments of the workability of arrangements by parents whose child was 15-17 years old and experiencing shared care time involving more nights with one parent than with the other.

7 The only other response option offered to these respondents was that the inter-parental relationship was "distant".

8 Parents were asked whether the other parent had abused them emotionally before or during the separation and whether the other parent had hurt them physically before the separation. Emotional abuse experiences were measured by 10 items that covered: (a) preventing the respondent from contacting family or friends, using the telephone or car, or having knowledge of, or access to, money; (b) insulting the respondent with intent to shame, belittle or humiliate; (c) threatening to harm the children, other family members or friends, their pets, or themselves; or (d) damaging or destroying property.

9 In addition, the mothers' reports suggested that fathers with shared care-time arrangements were less likely to have been very involved in their child's life prior to separation compared with fathers with most or all of the care time at the time of the survey, whereas the fathers' reports suggested little difference in the pre-separation involvement levels of mothers with shared care-time arrangements and those with most or all of the care time.

10 The safety issues referred to those linked with ongoing contact. Where the child never saw their father, 7% of fathers and 24% of mothers indicated that the question was not applicable. These respondents were treated as having no current safety concerns.

11 Inter-parental discussions represented the most commonly mentioned main pathway adopted by all other groups.

12 Trends for mothers who never saw their child were not derived owing to the small number of mothers represented in this group.

13 Parents were asked: (a) to rate their child's general health; and (b) how successful their child was in each of the following compared with other same-age children: learning or school work, getting along with other children his/her own age, and coping in most areas of life. Parents were also asked to answer a series of questions about their child's behaviours and socio-emotional difficulties (depending on child's age) and three scales were derived based on their responses (see Kaspiew et al., 2009, p. 266, for details).

14 The objective circumstances that were controlled covered the age and gender of the child and the following characteristics of the respondents: their age, educational attainment, employment status, relationship status at separation, Indigenous status, whether born overseas, and whether living with a partner when interviewed. The other circumstances that were controlled covered the respondents' perceptions regarding whether there had been mental health problems or substance misuse issues prior to separation; whether there had been a history of family violence; the quality of the inter-parental relationship; and whether they held safety concerns. The precise nature of these measures is described on p. 266 of Kaspiew et al. (2009).

15 Kaspiew et al. (2009) did not differentiate between the links between perceptions of child wellbeing and concerns about personal safety as opposed to the safety of the child.

16 This component study was conducted by McIntosh, Smyth, Wells & Long (2010).

17 These time points were: at intake for divorce mediation, three months after mediation and one and four years after mediation.

18 This component study was conducted by McIntosh, Smyth & Kelaher (2010). The LSAC consists of two age cohorts of children. In Wave 1 (conducted in 2004), approximately half the children were infants (aged 3-19 months) and half were 4-5 years old. The authors focused on: (a) data for the infant cohort in 2004; (b) data for the infant cohort when aged 2-3 years old (collected in 2006); and (c) data for the infant cohort when aged 4-5 years old (collected in 2008), in combination with data collected in 2004 for the older cohort (aged 4-5 years at the time).

References

- Amato, P. R. (2005). The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional wellbeing of the next generation. Future of Children, 15(2), 75-96.

- Amato, P. R., & Gilbreth, J. (1999). Non-resident fathers and children's wellbeing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 557-573.

- Amato, P. R., Meyers, C., & Emery, R. E. (2009). Changes in non-resident father-child contact from 1976 to 2002. Family Relations, 58, 41-53.

- Bauserman, R. (2002). Child adjustment in joint-custody versus sole-custody arrangements: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(1), 91-102.

- Cashmore, J., Parkinson, P., Weston, R., Patulny, R., Redmond, G., Qu, L., Baxter, J., Rajkovic, M., Sitek, T., & Katz, I. (2010). Shared-care parenting arrangements since the 2006 family law reforms. Report to the Australian Government Attorney-General's Department. Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales.

- Gilchrist, E. (2009). Implicit thinking about implicit theories in intimate partner violence. Psychology, Crime & Law, 15(2&3), 131-145.

- Gilmore, S. (2006). Contact/shared residence and child well-being: Research evidence and its implications for legal decision-making. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 20(3), 344-365.

- Grych, J. H. (2005). Inter-parental conflict as a risk factor for child maladjustment: Implications for the development of prevention programs. Family Court Review, 43(1), 97-108.

- Hartson, J. (2010). Children with two homes: Creating developmentally appropriate parenting plans for children ages zero to two. American Journal of Family Law, 23(4), 191-199.

- Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., Qu, L., & the Family Law Evaluation Team. (2009). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Kushner, M. A. (2009). A review of the empirical literature about child development and adjustment post separation. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 60, 496-516.

- McIntosh, J., & Chisholm, R. (2008). Cautionary notes on the shared care of children in conflicted parental separations. Journal of Family Studies, 14(1), 37-52.

- McIntosh, J., Smyth, B., & Kelaher, M. (2010). Parenting arrangements post-separation: Patterns and developmental outcomes, Part II. Relationships between overnight care patterns and psycho-emotional development in infants and young children. In J. McIntosh, B. Smyth, M. Kelaher, Y. Wells, & C. Long (2010). Post-separation parenting arrangements and developmental outcomes for infants and children. Collected Reports (pp. 85-169). Report to the Australian Government Attorney-General's Department. Attorney-General's Department: Canberra.

- McIntosh, J., Smyth, B., Wells, Y., & Long, C. (2010). Parenting arrangements post-separation: patterns and developmental outcomes, Part I. A longitudinal study of school-aged children in high-conflict divorce. In J. McIntosh, B. Smyth, M. Kelaher, Y. Wells, & C. Long, (2010). Post-separation parenting arrangements and developmental outcomes for infants and children. Collected Reports (pp.23-84). Report to the Australian Government Attorney-General's Department. Attorney-General's Department: Canberra.

- McIntosh, J., Smyth, B., Kelaher, M., Wells. Y., & Long, C. (2010). Post-separation parenting arrangements and developmental outcomes for infants and children. Collected Reports. Report to the Australian Government Attorney-General's Department. Attorney-General's Department: Canberra.

- Potter, D. (2010). Psychosocial wellbeing and the relationship between divorce and children's academic achievement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(4), 933-946.

- Ruddock, P. MP (2005, 8 December). Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Bill 2005. Second Reading Speech, Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives.

- Smart, C. (2004). Equal shares: Rights for fathers or recognition for children? Critical Social Policy, 24(4), 484-503.

- Sobolewski, J. M., & King, V. (2005). The importance of the coparental relationship for non-resident fathers' ties to children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1196-1212.

Ruth Weston, R., Qu, L., Gray, M., Kaspiew, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K. (2011). Care-time arrangements after the 2006 reforms: Implications for children and their parents. Family Matters, 86, 19-32.