Persistent work-family strain among Australian mothers

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

March 2011

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Achieving work and family life balance has been the focal theme of Australian Government policy work and social research for the last decade, particularly for mothers of dependent children, with their increasing labour force participation. One key focus of research on mothers' labour force participation is work-family strain. The aim of this present paper is to improve our understanding of persistent work-family strain by identifying mothers who are most at risk of experiencing long-term tension between work and family responsibilities, and comparing their characteristics and circumstances with mothers whose experience of work and family tension was relatively brief.

Achieving work and family life balance was not only the ultimate BBQ-stopper conversation of the last decade; it was also the focal theme of Australian Government policy work and social research (e.g., Alexander & Baxter, 2005; Baxter, Gray, Alexander, Strazdins, & Bittman, 2007; Baxter, 2009; Bowman, 2009; Losoncz & Bortolotto, 2009; Pocock, Skinner, & Williams, 2007; Reynolds & Aletraris, 2007; Strazdins et al., 2008). Of particular interest are mothers of dependent children, whose labour force participation has increased markedly over the last quarter of a century (ABS, 2006). At the same time, most mothers are retaining their primary responsibility for family care and domestic matters (de Vaus, 2009).

One key focus of research on mothers' labour force participation is work-family strain. Using the 2005 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey data, Losoncz and Bortolotto (2009) found that nearly 30% of Australian mothers in paid work experienced a strong tension between work and family responsibilities. Self-reports from these mothers indicated reduced physical and mental health and low satisfaction with family life and parenthood compared with other working mothers, who reported low work-family tension.

Subsequent longitudinal analysis over six years found that while the proportion of mothers reporting high tension between work and family responsibilities is constant, the transition of individual mothers from high to low work-family strain groups is relatively high (Losoncz, 2009a). The duration of time spent experiencing high work-family strain is important. While short- and long-term work-family strain are strongly related, they are a different phenomena. The characteristics of mothers experiencing long- versus short-term work-family strain are presumably different and so are their work and family environments. The impact of long-term work-family strain is also likely to be different from the impact of strain that is short-lived. From a policy perspective, different strategies are likely to be needed to assist mothers experiencing temporary versus persistent work-family strain.

The aim of this present paper is to improve our understanding of persistent work-family strain by identifying mothers who are most at risk of experiencing long-term tension between work and family responsibilities, and comparing their characteristics and circumstances with mothers whose experience of work and family tension was relatively brief.

Factors contributing to work-family strain

While Australian research to date has not considered long-term work-family strain specifically, the literature on work and family tension and its predictors has advanced considerably in recent years. Researchers have identified a number of factors related to parents' experiences of work-family conflict, both in the home and work environment.

A frequently noted factor is long working hours and the negative impact this has on family life, as parents are unable to allocate the necessary time and energy to maintain family relationships. For example, Pocock and her colleagues (2007) found a strong and consistent association between long work hours (more than 45 hours per week) and poorer life outcomes. While Gray, Qu, Stanton, and Weston (2004) found that fathers working more than 40 hours per week reported more negative effects of work on family than fathers working 35-40 hours, the association between long working hours and wellbeing was negligible on most other measures. Importantly, the study found that for fathers working very long hours (more than 60 hours per week) an important predictor of their own wellbeing and that of their families was their satisfaction with their work hours. This corresponds with findings from other researchers reporting that workers who have a poor "fit" between their actual and preferred hours are more likely to have poorer work and family life outcomes (Fagan & Burchell, 2002; Messenger, 2004; Pocock et al., 2007).

While long working hours may have a negative impact on family and personal wellbeing, other aspects of work can be equally influential. Quality, complexity and skill level of the job, flexibility and pace of work, job security and control over work schedule are all important contributing factors (Allan, Loudoun, & Peetz, 2007; Galinsky, 2005; Strazdins et al., 2008).

The level of tension between work and family responsibilities also varies among mothers, depending on their characteristics, family types and socio-economic circumstances. Strazdins and her colleagues (2008) found that lone mothers in paid work, particularly those with preschool-aged children, tend to experience more work-family strain than employed mothers with a partner.

Somewhat interestingly, parents from more advantaged families tend to experience more work-to-family strain than their relatively disadvantaged counterparts (Strazdins et al., 2008). This is an interesting association to consider. Typically, socio-economic disadvantage is linked to poor work conditions - a predictor of high work-family tension. In fact, the research by Strazdins and her colleagues confirmed this association, especially among females. Specifically, socio-economically disadvantaged parents were more likely to be employed casually, to feel insecure about their job, and to report lower levels of job control. Job security disparity was particularly marked for mothers. But this positive association between socio-economic disadvantage and poor work conditions did not transfer into higher levels of work-family tension among mothers in relatively disadvantaged families.

From these results, it appears that the higher prevalence of work-to-family strain among advantaged families may be due to the longer hours spent at work by parents in those families. Typically, long work hours are more common in high-skilled jobs, while low-skilled jobs are more likely to be part-time and therefore involve fewer work hours (Gray, Qu, Stanton, & Weston, 2004). Indeed, Strazdins et al. (2008) found that fathers from more economically advantaged families tend to work around two hours more per week, while mothers from advantaged families tend to work three to four hours more per week than their less economically advantaged counterparts.

While the adverse impact of work on family life is more widespread than the other way around (Pocock et al., 2007), the home environment can also influence work performance and the extent to which work is experienced as enjoyable and rewarding. Examples of factors that increase home-to-work spillover include: the care needs of young children and elderly relatives (Barnett, 1994; Barnett & Marshall, 1992a, 1992b), housework and its distribution within families (Coltrane, 2000), and the perceived quality of each parent's role, both as a spouse and as a parent (Milkie & Peltola, 1999).

Another factor influencing work-family conflict, particularly among mothers, is poor parental identification with family and work preferences (Cinamon & Rich, 2002). Generally speaking, it has been suggested that lifestyle preferences may contribute to the degree of tension between work and family; that is, people whose reality does not match their preference tend to experience higher levels of tension (Brunton, 2006).

It is evident from the above studies that the work and family life experiences of Australian mothers are diverse and shaped by a wide range of factors. To capture the common thread of these experiences, Losoncz and Bortolotto (2009) used cluster analysis to identify major homogenous groups among Australian working mothers. Their research identified six major clusters/groups of working mothers, each with distinctive profiles in terms of their work-family balance experience. A summary on cluster analysis and on the six clusters identified by Losoncz & Bortolotto (2009) is provided in Boxes 1 and 2 respectively. Two of the six clusters, or 36% of mothers, managed their work and family commitments successfully, while two other clusters, or 27% of working mothers, experienced high tension between their work and family commitments. Mothers in the high work-family tension clusters (the "Aspiring and struggling" and "Indifferent and struggling" clusters) were characterised by long working hours, high work overload, perceived lack of support from others, lower self-reported health status, and low satisfaction with family life and parenthood.

The current paper will extend this initial cross-sectional cluster analysis with the aim of exploring long-term work-family strain among Australian mothers. Using the six clusters identified through the first six waves of the HILDA survey and longitudinal analysis techniques, the paper will explore the nature and extent of transitioning between clusters, with particular emphasis on the two high work-family tension clusters. Three main themes will be investigated:

- transition pathways between clusters;

- predictors of short-term versus long-term work-family strain; and

- characteristics of mothers experiencing persistent work-family strain.

Box 1: Cluster analysis

Method

Cluster analysis is an exploratory statistical technique that groups respondents based on their characteristics, rather than variables, to detect natural groupings in the data. Clustering simplifies complex data and can reveal patterns in multi-faceted phenomena by identifying how types of people are similar and dissimilar (Adlaf & Zdanowich, 1999).

One of the benefits of this approach is that it enriches our understanding of how a set of concepts finds expression in different kinds of people. In doing so, it suggests possible causal relationships, which may assist in developing hypotheses for future research (Adlaf & Zdanowich, 1999; Berry, 2008). To enhance the research utility of clusters, initial cluster analysis is usually followed by a number of other techniques, such as descriptive analysis, multivariate analysis of variance or regression analysis.

Classifying working mothers into largely homogenous groups based on their work-life experience can advance our understanding of the connection between work-life balance, economic productivity and the wellbeing of families and individuals, to enable policy development.

Indicators used for cluster analysis of work and family life balance of Australian mothers

In the current study, 13 statements (adopted from Marshall & Barnett, 1993) on combining work and family responsibilities were used to formulate the clusters. Mothers in paid work were asked to indicate on a seven-point rating scale how strongly they agree or disagree with each statement. The 13 statements used for the cluster analysis in this study are:

- Both work and family responsibilities makes me a more well-rounded person.

- Both work and family responsibilities give my life more variety.

- Managing work and family responsibilities as well as I do makes me feel competent.

- My work has a positive effect on my children.

- The fact that I am working makes me a better parent.

- Working helps me to better appreciate the time I spend with my children.

- With the requirements of my job, I miss out on home or family activities that I would prefer to participate in. (Reverse coded)

- With the requirements of my job, my family time is less enjoyable and more pressured. (Reverse coded)

- Working leaves me with too little time or energy to be the kind of parent I want to be. (Reverse coded)

- Working causes me to miss out on some of the rewarding aspects of being a parent. (Reverse coded)

- I worry about what goes on with my children while I'm at work. (Reverse coded)

- With my family responsibilities, the time I spend working is less enjoyable and more pressured. (Reverse coded)

- With my family responsibilities, I have to turn down work activities or opportunities that I would prefer to take on. (Reverse coded)

Items 7-13 were reverse coded for analysis only, to provide a more consistent output (i.e., a higher score would always mean a more desirable outcome).

Box 2: The six-cluster solution of Australian working mothers

Highly functioning and fulfilled cluster (20%)

Mothers in this cluster highly value their working mother role (statements 1-6 in Box 1) and are successful at managing the practical impact of the work-life nexus (statements 7-13 in Box 1).

Descriptive analysis found that mothers in this cluster have the lowest level of stress at work. The number of hours they spend at work (an average 27 hours per week) is just below the average of the total sample, while the time they spend on domestic tasks is well below the total average. Their partners tend to spend average hours at work and on domestic tasks. Mothers in this cluster reported the highest levels of satisfaction with family relationships, division of household tasks, and support received from others. They also have the highest scores for physical and mental health.

Indifferent yet successful cluster (16%)

Mothers in this cluster place a relatively low value on their working mother role, but they manage the day-to-day impact of the role just as well as mothers in the previous cluster. So, while these mothers tend to be indifferent to the working mother ideal, they are successful at it.

In terms of their characteristics, mothers in this cluster are the most likely to be married, to be self-employed or working for a family business, and to be a casual worker. They work the shortest number of hours (21 hours per week, on average), and the majority are happy with these hours. While they spend the highest number of hours on domestic tasks, their combined paid and unpaid working hours are still the lowest. Mothers in this cluster appear to have a gender-based domestic arrangement with their partners, who spend above-average time at work but below-average hours on domestic tasks. Mothers in this cluster tend to find parenthood a positive experience.

Aspiring and struggling cluster (15%)

Mothers in this cluster place a high value on being a working mother. However, when it comes to the day-to-day aspects of their life, they report a very strong tension between work and family.

This cluster has the highest proportion of mothers working more than 45 hours per week. Mothers in this group spend the longest hours at work (an average 33 hours per week), and average hours on domestic tasks, leading to the highest combined (paid and unpaid) work hours of all the clusters. Even though mothers in this cluster have high occupational status and a high level of job control, they also have the highest level of work overload and stress at work. Mothers in this cluster reported the lowest physical and mental health scores and low satisfaction with family relationships, parenthood and support from others.

Indifferent and struggling cluster (12%)

Mothers in this cluster place a relatively low value on the working mother role and, when it comes to the practical, day-to-day aspects of their life, they report the strongest tension between work and family.

Mothers in this cluster are the most likely to be single or widowed. They work the second longest hours (31 hours per week, on average) and over half of them want to work fewer hours. They reported the second highest level of overload and work stress, low levels of job control and flexibility, and the lowest level of work satisfaction. Mothers in this cluster work the second longest hours and, if partnered, their partners also tend to work above-average hours. At the same time, the average equivalised household disposable income of this cluster is the lowest. Mothers in this cluster reported the lowest satisfaction with family relationships, parenthood and support from others, and low physical and mental health.

Treading water cluster (20%)

Mothers in this cluster are just below the average both in terms of the value they place on their working mother role and the extent to which they are successful at managing the practical impact of the working mother role. So, while they experience considerable tension between work and family life, they are coping with it.

In terms of their characteristics, they reported average values on socio-demographic, work and family indicators. Mothers in this cluster spend average hours at work (29 hours per week, on average) and on domestic tasks. Their partners also tend to work average hours. Mothers in this cluster reported an average level of satisfaction with family relationships, division of household tasks and level of support from others, as well as average physical and mental health scores.

Guilty copers cluster (17%)

Mothers in this cluster place a relatively high value on the working mother role. In terms of managing the practical aspects of the work-life nexus, they reported scores well above the average. However, they often worry about their children while at work, and feel that working leaves them with little energy to be the type of parent they want to be.

Mothers in this cluster were found to be similar in nearly all their characteristics to the overall sample. The only notable difference is the high level of conscientiousness they reported on the Personality Trait Scale (Losoncz, 2009b), which may explain their tendency to worry about their children while at work.

Data and methods

Data for this analysis was drawn from the first six waves (2001-06) of the HILDA survey,1 a nationally representative household panel survey focusing on employment, family and income issues. The sample for this study - approximately 1,300 mothers in each wave - was limited to working mothers (partnered and un-partnered) with parenting responsibilities for children aged 17 years or less. The respondents completed a 13-item questionnaire on work-family balance in a self-completion part of the survey. The items were included in the survey to measure three themes relating to the impact of combining work and family responsibilities on self, work and family.2

The focal method in this research is cluster analysis (see Box 1). Cluster analysis groups individuals according to their similarity on selected features - in this instance their responses to the 13 work-life balance statements. A two-stage analysis was applied. In the first (partitioning) stage, a hierarchical procedure was used to investigate if the six clusters identified by Losoncz and Bortolotto (2009) using Wave 5 HILDA data would fit the data in each of the six waves. Cluster analysis applied independently to each wave of data came up with the same set of clusters, with only minimal variation in cluster scores across the six waves.3 The paper by Losoncz and Bortolotto (2009) provides a detailed account of the development of the six clusters, including data source, measures, formulation and description of clusters.

In the second (fine tuning) stage, respondents were reassigned around the common seed points (across the six waves) of each cluster. The purpose of this second step was to create more homogenous, or alike, groups and to increase comparability between waves. Other statistical methods employed in this paper included descriptive statistics and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Limitations of the study

A main limitation of the study is that it did not include a sample of mothers who did not join the workforce because of the anticipated or actual tension between work and family responsibilities. As such, it may under-report the proportion of mothers who see their engagement in the workforce as an important aspect of their life, but consider work and family responsibilities too difficult to manage together. This limitation was addressed in part by examining the work-family balance clustering of mothers (re-)entering employment. Work-family balance clustering of mothers just prior to leaving employment was also examined in more detail in a recent social policy note (Losoncz & Graham, 2010).

Results

Extent of transition and transition pathways between clusters

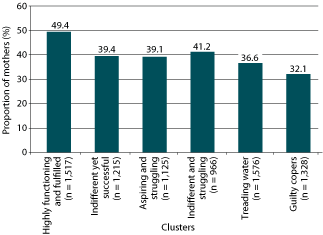

How variable are mothers' experiences of work-family balance? Is it a short- or a long-term experience for most mothers? One indicator to answer this question is the proportion of mothers remaining in the same cluster from one year to the next. On average, around 40% of mothers stay in the same cluster as in the previous year. However, there is a notable variation in their likelihood of transition depending on the cluster they were in. The least transient group is the "Highly functioning and fulfilled" cluster, where nearly half of the mothers stayed in that cluster for the following year. In contrast, the "Guilty copers" cluster appears to be the most transient group, with only 32% of mothers remaining in this cluster in the subsequent year (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of mothers who remained in the same cluster between any two waves

Source: HILDA Waves 1-6

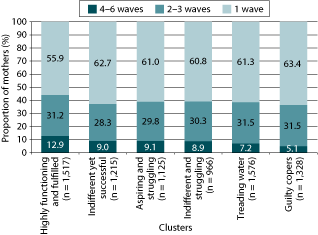

The proportion of mothers who indicated that they were in the same cluster for at least four of the six waves represents another indicator of the level of stability of the cluster membership. Mothers in the "Highly functioning and fulfilled" cluster are the most likely to remain in the cluster for an extended period. Of the mothers who were in this cluster for at least one wave, as many as 13% reported to spend an additional three or more waves in the cluster, compared with only 5% in the "Guilty copers" cluster (Figure 2). It appears that irrespective of the methodology used, experiencing low or no tension between work-family responsibilities is more lasting than high work-family tension or feeling guilty about work commitments and its impact on parenting.

Figure 2: Proportion of mothers staying in each cluster by number of waves

Source: HILDA Waves 1-6

Which are the most frequent pathways for mothers moving between clusters? The pathways between clusters are too numerous to be presented in this paper, but there are two emergent patterns worth discussing. First, the cluster distribution of mothers who (re-)entered paid work after caring for a newborn was comparable to the cluster distribution of the total sample (Table 1). Although these mothers were least likely to transit into the two clusters experiencing strong tension in managing their work and family responsibilities, and were most likely to go into the clusters that are most successful at managing their work and family responsibilities, this difference in distribution did not reach statistical significance. Mothers who (re-)entered, paid work, who had not previously been caring for a newborn were also less likely to experience strong tension in managing their work and family responsibilities. Instead, they were considerably more likely to go into the "Indifferent yet successful" cluster (24% compared to the sample average of 16%). For this group, the difference in distribution was statistically significant (x2 (5, N = ,569) = 36.8, p < .05).

| Cluster | Average cluster distribution over 6 waves for total sample | Cluster distribution upon re/entering paid work after caring for a newborn | Cluster distribution upon re/entering paid work after other reasons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly functioning and fulfilled | 19.7 | 22.3 | 19.9 |

| Indifferent yet successful | 15.7 | 18.4 | 24.1 |

| Aspiring and struggling | 14.6 | 10.7 | 10.0 |

| Indifferent and struggling | 12.5 | 9.7 | 10.9 |

| Treading water | 20.4 | 20.4 | 18.3 |

| Guilty copers | 17.2 | 18.4 | 16.9 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of observations | 206 | 569 |

Source: HILDA, Waves 1-6

The second noteworthy trend is the low level of direct transition between the clusters in which mothers struggle to manage their work and family responsibilities and the clusters that are most successful at it. Mothers from the "Aspiring and struggling" cluster showed a relatively low transition into the "Highly functioning and fulfilled" cluster (8%), but a much higher transition into the "Indifferent and struggling" cluster (20%). Similarly, transiting from the "Indifferent and struggling" cluster into the "Indifferent yet successful" cluster was much lower (8%) than into the "Aspiring and struggling" cluster (26%).4 This indicates that the value that mothers appear to place on their working-mother role is more changeable than their view of the day-to-day impact of managing their work and parenting roles. It should be noted that the two "middle clusters" ("Treading water" and "Guilty copers") had the highest transition to and from other clusters, supporting the more transitory nature of these experiences.

Predictors of short-term versus long-term work-family strain

The relatively small proportion of mothers reporting a transition into a much-improved work-family balance cluster, irrespective of the change in their work-role identification, raises the question of which changes are associated with an improved work and family life balance. To investigate this question, the two high work-family tension clusters were combined, as well as the two low and medium work-family strain clusters. Analysis of year-to-year transition5 from the two high work-family tension clusters found that about half (49%) of the mothers remained in a high work-family tension cluster in the subsequent year. A further 42% moved to an average work-family tension cluster, and only 9% of mothers transferred to a low work-family tension cluster.

Of particular interest was the relationship status of mothers (i.e., lone or coupled), working hours (paid and unpaid) of adults in the family, and mothers' report of perceived help from others.

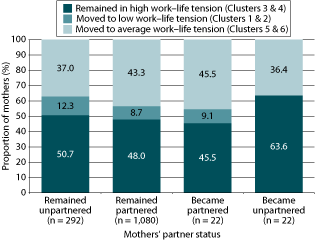

In terms of relationship status, mothers who became un-partnered between the waves were the least likely to report an improved work and family life balance (Figure 3). As many as 64% of these mothers remained in a high work-family tension cluster compared to only 46% of mothers who become partnered between the waves. Furthermore, none of the mothers who became un-partnered between waves transited directly into a low work-family tension cluster, contrasting with every other category where a small proportion of mothers did move to a low work-family tension cluster. For example, of the mothers who become partnered between waves, just less than 10% moved to a low work-family tension cluster. Similarly, of the mothers who remained un-partnered, a small but notable proportion did move to a low work-family tension cluster. These results tend to indicate that it may be the event of the separation itself, rather than being un-partnered, that increases the likelihood of prolonged work-family strain among mothers in paid work.

Figure 3: Cluster transitions by change in relationship status among mothers in high work-family tension cluster

Note: Lack of comprehensive outcome measures in the first wave of HILDA prevented the use of Wave 1.

Source: HILDA, Waves 2-6

Average paid working hours per adults in the family, and distribution of paid and unpaid working hours between mothers and their partners, are all significant predictors of transitioning to a low or average work-family tension cluster (Table 2). Families where mothers moved to low work-family tension clusters reported a 3.1-hour reduction in the average paid working hours of adults in the family per week, compared with a 1.6-hour increase by families where mothers remained in a high tension cluster. In terms of the distribution of workload between mothers and their partners, mothers who moved to low work-family tension clusters reported, on average, a 4.8-hour reduction in their combined paid and unpaid working hours while their partner reported a corresponding 4.6-hour increase in their combined paid and unpaid working hours. In contrast, mothers who remained in high tension clusters reported an average of 3.0-hour increase in their paid and unpaid working hours and their partner reported an additional 1.9-hour increase.

| Change in ... | Remained in high work-family tension (Clusters 3 & 4) | Moved to low work-family tension (Clusters 1 & 2) | Moved to average work-family tension (Clusters 5 & 6) | Statistically significant difference ^ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average paid working hours per adults in family | +1.60 | -3.06 | -1.37 | 1-2 1-3 |

| Mother's paid and unpaid working hours | +3.03 | -4.82 | -1.39 | 1-2 1-3 |

| Partner's paid and unpaid working hours | +1.92 | +4.58 | -1.50 | Non-significant |

| Mother's paid working and commuting to work hours | +1.38 | -5.92 | -1.28 | All |

| Mother's unpaid working hours | +0.49 | +1.24 | +0.33 | Non-significant |

| Partner's paid working and commuting to work hours | +1.54 | +2.63 | -1.31 | Non-significant |

| Partner's unpaid working hours | +0.43 | +1.98 | -0.31 | Non-significant |

| Level of perceived help from others | -0.12 | +0.58 | +0.20 | 1-2 1-3 |

| No. of observations | 347 | 64 | 297 |

Note: Lack of comprehensive outcome measures in the first wave of HILDA prevented the use of Wave 1. ^ Significant differences are tested with Tukey's method ( < .05).

Source: HILDA Waves 2-6

It appears that the change in the balance of paid and unpaid working hours between partners primarily came from a reduction in paid working hours by mothers (although their unpaid working hours did rise slightly) and an increase in both paid and unpaid working hours by fathers. The change in the balance of working hours (paid and unpaid) within the family was also reflected in mothers' report of support from others. Mothers who moved to a lower work-life tension cluster reported a significant increase in the level of perceived help from others (Table 2).6

Characteristics of mothers experiencing persistent work-family strain

The last section of results reported in this paper looks at the characteristics of mothers who experience persistent work-family strain. Of the 27% of working mothers struggling with managing work and family responsibilities at any one time (i.e., mothers in the "Aspiring and struggling" and "Indifferent and struggling" clusters), one-quarter of those, or 6% of all working mothers, continued to struggle with balancing work and family life for more than four years.

Characteristics and circumstances of these two groups are reported in Table 3. One of the strongest predictors of remaining in a high work-family tension cluster is having a youngest child between the ages of 6 and 11 years in the household. Anecdotal evidence suggests that working mothers tend to find the demands associated with early school years stressful. This finding lends quantitative support to this proposition.

| Remained in high work-family tension (Clusters 3 & 4) for: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 wave only | 4 or more waves (values in first wave) | 4 or more waves (values in last wave) | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||

| Age of youngest child in the household | |||

| 0-1 years | 11.29 | 7.50 | n.a |

| 2-5 years | 23.97 | 21.25 | n.a |

| 6-11 years | 35.54 | 56.25 | n.a |

| 12 years and over | 29.20 | 15.00 | n.a |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | n.a |

| Significant differences ^ | 0.005 | ||

| Education level of mother | |||

| Degree or higher | 30.85 | 38.75 | n.a |

| Diploma | 9.64 | 15.00 | n.a |

| Certificate | 19.56 | 13.75 | n.a |

| Year 12 | 17.08 | 10.00 | n.a |

| Year 11 or below | 22.87 | 22.50 | n.a |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | n.a |

| Significant differences ^ | 0.1 | ||

| Mother's age, total number of own children under 5 and 15, and household disposable income did not show observable differences | |||

| Paid and unpaid working hours | |||

| Average working hours of adults in the family per week* | 38.69 | 41.67 | 44.96 |

| Mother's hours per week in paid and unpaid work* | 61.60 | 62.95 | 66.83 |

| Mother's working hours and commuting to main job per week* | 34.39 | 37.35 | 41.62 |

| Mother's hours per week doing housework, errands and outdoor tasks* | 25.71 | 25.09 | 24.83 |

| Partner's hours per week in paid and unpaid work | 61.66 | 62.55 | 64.52 |

| Partner's working hours and commuting to main job per week | 46.08 | 48.46 | 48.68 |

| Partner's hours per week doing housework, errands and outdoor tasks | 15.28 | 13.61 | 15.70 |

| Self-reported health and satisfaction | |||

| Overall job satisfaction* | 51.56 | 57.15 | 59.91 |

| Life satisfaction | 7.44 | 7.19 | 7.33 |

| Satisfaction with division of household tasks with partner | 1.89 | 1.73 | 1.91 |

| Often need help from other people, but can't get it | 2.70 | 3.00 | 3.04 |

| Physical health* | 77.39 | 75.91 | 71.22 |

| Mental health* | 78.13 | 75.38 | 72.46 |

| No. of observations | 363 | 80 | 80 |

Notes:^ Pearson's chi-square. * Statistically significant differences at the .05 level.

Source: HILDA Waves 2-6

Another statistically significant socio-demographic predictor is the education level of mothers. Mothers with a higher level of education are more likely to experience an extended period of work-family strain. However, mothers' age, total number of own children under the ages of 5 and 15 years, and household disposable income did not show an observable or statistically significant difference.

Paid and unpaid working hours showed a similar pattern to that presented in the previous section. That is, increasing number of working hours in the household, particularly increasing paid working hours by the mother, was evident among mothers with ongoing work-family strain. Mothers with ongoing work-family strain generally started out with higher paid working hours, which increased even further through subsequent waves. For this group, the increase in paid working hours was not balanced by a reduction in mothers' hours per week spent doing housework, errands and outdoor tasks, or a reduction in their partner's working hours. However, there was a notable increase (just over 2 hours per week) in their partners' hours spent doing housework, errands and outdoor tasks.

Interestingly, job satisfaction, but not life satisfaction, reported by mothers with on-going work-family strain was significantly higher to start with and increased further through the years. At the same time, their self-reported physical and mental health showed a significant decline.

Discussion

This paper contributes to the growing evidence base relating to work and family life balance using cluster analysis. Extending earlier research by the author, the current project examined the transition of mothers between the six work-life balance clusters, identified by Losoncz and Bortolotto (2009), over six years.

The initial cluster analysis by Losoncz and Bortolotto (2009), summarised in this paper, confirmed the diversity in characteristics and circumstances of Australian working mothers. It also offered a typology of working mothers based on the multiple dimensions of their work and family life.

Thirty-six per cent of mothers, making up two of the clusters, reported successfully managing their work and family responsibilities. These mothers tend to have low combined hours of paid and unpaid work and low levels of work stress. A further 27% of mothers experience a strong tension between work and family commitments. Mothers in these two clusters tend to have long working hours and high work overload. Further, they have little or no support from others, often because they are un-partnered, or because their partner's working hours do not adapt to balance their long working hours. In these families, both parents work long hours while the mother retains responsibility for the majority of unpaid work.

While the same six clusters emerged consistently through the six waves, longitudinal analysis of individual mothers over six years revealed a relatively high transition between clusters. Fewer than 40% of mothers remained in the same cluster in any two waves, while just more than 8% of mothers remained in the same cluster for at least four waves. The observable difference between low and high conflict clusters tends to indicate that low or no work-family conflict is a more durable experience than the work-family strain or feelings of guilt over work commitments and its impact on parenting.

Another finding from this study is the effect of certain life cycle events on work and family life balance. The actual event of separation, rather than being un-partnered in general, is one of the predictors of prolonged work-family strain among mothers in paid work. Another strong predictor is the youngest child in the family being between 6 and 11 years of age. This association may partly be explained by the tendency for mothers to enter full-time work once their child turns six years old (or once they begin school). There is anecdotal evidence that a child's early school years are associated with increased demands on working parents. Findings from this research lend quantitative support to this proposition. The findings also correspond with the findings of Strazdins and colleagues (2008), which suggests that psychological distress and strain related to conflicting work and family demands are higher among mothers of preschoolers compared to mothers of infants or adolescents. These findings suggest that mothers in paid work may require more intense assistance in relation to particularly demanding periods of the work-family life cycle; for example, during the time of family break-ups or when their children enter primary school.

A particular focus of this paper is mothers experiencing persistent work-family strain. While just under one-third of working mothers reported struggling with managing work and family responsibilities at any one time, not all of these mothers are at risk of persistent work-family strain. In fact, the majority of these mothers moved onto a more positive experience within a couple of years. Nevertheless, just less than one-quarter of these mothers, or 6% of all working mothers, continued to struggle with balancing work and family life for more than four years. These mothers with long-term difficulties managing work and family responsibilities are most likely to require more targeted assistance and, ultimately, external support.

Not surprisingly, mothers transitioning from a high work-family tension cluster are much more likely to transfer to a cluster with an average, rather than a low, level of work-family tension. Transition from a high work-family tension cluster to a low-tension cluster was strongly related to a substantial reduction in the paid working hours of mothers, although their levels of time spent doing household unpaid work (housework, errands and outdoor tasks) did rise slightly, as did their partner's paid and unpaid working hours. The shift in the balance of paid and unpaid working hours in families where mothers transited to a low work-family tension cluster was also reflected in the increased perceived help from others, including partners. This points to the merit of more equally shared responsibilities for work, family and caring within couples, and the importance of support from others within and outside the home, such as grandparents and paid care.

At a more fundamental level, the strong positive relationship between reduced workforce engagement and subsequent improvement in work and family life balance among mothers tends to indicate that balancing caring and work responsibilities is still seen as a responsibility to be undertaken by the mother rather than a responsibility undertaken by both parents. These results correspond with the findings of Strazdins et al. (2008), which suggest that mothers' employment is conducted in a different "time context" to that of fathers. That is, mothers modulate their work hours according to their children's ages and partner's work, and hold down jobs in the context of having partners with heavy work time commitments. The current study suggests when mothers fall short of adjusting their work hours in response to family and external demands they will risk being able to maintain a work and family life balance as well as their physical and mental wellbeing.

But not all mothers want, or are in the position to be able, to adjust their working hours in response to family and external commitments. Indeed, this research suggests that some mothers, particularly mothers with a strong attachment to the workforce and high job satisfaction, persist to work longer hours while experiencing continuing high work-family tension and a decline in their wellbeing. This indicates that approaches rooted in reduced engagement with the workforce that enables mothers to afford time to take on primary responsibility for family domestic matters is not an adequate solution for all mothers and families. This resonates with findings from recent studies suggesting that the relationship between part-time work and work-family balance is often subject to job context. That is, non-career women gain a far greater benefit from part-time work than professional women whose greater work demands constrain the benefits they derive from part-time schedules (Duxbury & Higgins, 2008; Higgins, Duxbury & Johnson, 2000).

These results suggest that existing approaches, such as part-time schedules, flexible working hours, and attempts to reconfigure the balance of paid and unpaid working hours within couples, need to be complemented with new initiatives.

In conclusion, Australian mothers in recent decades have greatly increased their participation in the labour market. Fathers, however, have not increased their participation in unpaid household work to a matching degree. But, without equal sharing of the dual roles of earner and carer between mothers and fathers, mothers will inevitably feel the work-family tension more keenly. Furthermore, institutional and structural changes supporting mothers' increased workforce participation are few and slow coming. Consequently, working mothers faced with the challenge of reconciling family and work commitments are often forced to find individual solutions. However, work and family life balance is not a problem specific to individual families. Rather, it is a universal problem shared by many families, and as such it requires institutional and structural changes supported by society as a whole.

Endnotes

1 For more information, see Watson and Woden (2002).

2 For more information on the 13 items see HILDA W5 Self Completion Questionnaire at <www.melbourneinstitute.com/hilda/qaires/q5.html>.

3 Mean scores for the 13 work-life balance statements for each cluster over the six waves are available from the author on request.

4 Due to the small cell sample size, a test to establish statistical significance was not run.

5 In HILDA waves 2-6, there were 1,271 episodes where a mother either moved or remained in a high work-life tension cluster. However, a considerable number of these episodes were by the same mother. To avoid double counting analysis only included the first episode. This yielded a sample size of 708 episodes.

6 Measured on a seven-point scale.

References

- Adlaf, E. M., & Zdanowich, Y. M. (1999). A cluster-analytic study of substance problems and mental health among street youth. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 25, 639-60.

- Alexander, M., & Baxter, J. (2005). Impacts of work on family life among partnered parents of young children. Family Matters, 72, 18-25.

- Allan, C., Loudoun, R., & Peetz, D. (2007) Influences on work/non-work conflict. Journal of Sociology, 43(3), 219-239.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). Australian social trends 2006 (Cat. No. 4102.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Barnett, R. C. (1994). Home-to work spillover revisited: A study of full-time employed women in dual-earner couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 647-56.

- Barnett, R. C., & Marshall, N. L. (1992a). Men's job and partner roles: Spillover effects and psychological distress. Sex Roles, 27, 455-72.

- Barnett, R. C., & Marshall, N. L. (1992b). Worker and mother roles, spillover effects, and psychological distress. Women and Health, 18, 9-40.

- Baxter, J., Gray, M., Alexander, M., Strazdins, L. &, Bittman, M. (2007). Mothers and fathers with young children: Paid employment, caring and wellbeing (Social Policy Research Paper No 30). Canberra: Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Baxter, J. (2009). Mother's timing of return to work by leave use and pre-birth job characteristics. Journal of Family Studies, 15(2), 153-166.

- Berry, H. L. (2008). Twelve types of Australians and their socio-economic, psychosocial and health profiles. Paper prepared for the Australian Government Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Canberra.

- Bowman, D. D. (2009). The deal: Wives, entrepreneurial business and family life. Journal of Family Studies, 15(2), 167-176.

- Brunton, C. (2006). Work, family and parenting study: Research findings. New Zealand: Centre for Social Research and Evaluation, Ministry of Social Development.

- Cinamon, R. G., & Rich, Y. (2002). Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: Implications for work-family conflict. Sex Roles, 47, 531-41.

- Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1209-1233.

- de Vaus, D. (2009). Balancing family work and paid work: Gender-based equality in the new democratic family. Journal of Family Studies, 15(2), 118-121.

- Duxbury, L., & Higgins, C. (2008). Work-life balance in Australia in the new millennium: Rhetoric versus reality. Victoria: Beaton Consulting.

- Higgins, C., Duxbury, L., & Johnson, K. L. (2000). Part-time work for women: Does it really help balance work and family? Human Resource Management, 39(1), 17-32.

- Fagan, C., & Burchell, B. J. (2002). Gender, jobs and working conditions in the European Union. Dublin: European Foundation for Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

- Galinsky, E. (2005). Children's perspectives of employed mothers and fathers: Closing the gap between public debates and research findings. In D. F. Halpern & S. E. Murphy (Eds.), From work-family balance to work-family interaction: Changing the metaphor (pp. 219-237). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gray, M., Qu, L., Stanton, D., & Weston, R. (2004). Long work hours and the wellbeing of fathers and their families. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 7(2), 255-273.

- Losoncz, I. (2009a). Struggling to keep the balance: Work-life experience of Australian mothers in paid work between 2001 and 2006. Paper presented at the 2009 Australian Social Policy Conference, Melbourne, Victoria.

- Losoncz, I. (2009b). Personality traits in HILDA. Australian Social Policy, 8, 169-198.

- Losoncz, I., & Bortolotto, N. (2009). Work-life balance: The experience of Australian Working Mothers. Journal of Family Studies, 15(2), 122-138.

- Losoncz, I., & Graham, B. (2010). Work-life tension and its impact on the workforce participation of Australian mothers. Australian Social Policy, 9, 139-156.

- Marshall, N. L., & Barnett, R. C. (1993). Work-family strains and gains among two-earner couples. Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 64-78.

- Messenger, J. C. (2004). Working time and workers' preferences in industrialized countries: Finding the balance. London: Routledge.

- Milkie, M. A., & Peltola, P. (1999). Playing all the roles: Gender and work-family balancing act. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(2), 476-90.

- Pocock, B., Skinner, N., & Williams, P. (2007). Work, life and time: The Australian Work and Life Index, 2007. South Australia: Centre for Work + Life, Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia.

- Reynolds, J., & Aletraris, L. (2007). Work-family conflict, children, and hour mismatches in Australia. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 749-772.

- Strazdins, L., Lucas, N., Mathews, B., Berry, H., Rodgers, B., & Davies, A. (2008). Parent and child wellbeing and the influence of work and family arrangements: A three cohort study. Report to the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Canberra: Australian Government.

- Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2002). The Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey: Wave 1 survey methodology (HILDA Project Technical Paper Series No. 1/02). Melbourne University of Melbourne.

Losoncz, I. (2011). Persistent work-family strain among Australian mothers. Family Matters, 86, 79-88.