Do individual differences in temperament matter for Indigenous children?

The structure and function of temperament in Footprints in Time

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2012

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

It is well known that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter Indigenous) people suffer disproportionately from a range of physical and mental health issues (Thomson et al., 2012). Understanding the origin of these problems is fundamental to the development of effective policy, prevention and interventions that would "close the gap" in health and wellbeing between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Given the connection between adjustment in early childhood and later wellbeing (Power & Hertzman, 1997; Rutter, 1991), it is critical to identify factors that promote socio-emotional adjustment for Indigenous children. Research to date that has examined influences on adjustment in Indigenous children has most often focused on the effect of environmental factors, particularly those relating to social disadvantage or disparities in physical health (Priest, Mackean, Waters, Davis, & Riggs, 2009). Significantly less is known about the contribution of more normative psychological processes to socio-emotional wellbeing.

Studies of children from Western backgrounds have indicated that temperament may play an important role in children's wellbeing (e.g., Rothbart & Bates, 1998). At this stage, however, there is very little research on the nature and importance of temperament for Indigenous children. Drawing on data on children's temperament style and socio-emotional wellbeing from Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC), this study investigated the structure of temperament in Indigenous children as well as how temperament, along with parenting style, might be linked to their later emotional and behavioural adjustment. Where possible, comparisons were made with data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC).

Social and emotional adjustment in childhood

The connection between children's early emotional and social adjustment and later wellbeing is well established, with early behaviour providing good "signals" of later outcomes (Buchanan, Flouri, & Ten Brinke, 2002; Rutter, Kim-Cohen, & Maughan, 2006). In particular, when children experience emotional and behavioural problems in their early years, there is potential for these difficulties to become entrenched and affect their later development (Fischer, Rolf, Hasazi, & Cummings, 1984; Roza, Hofstra, Ende, & Verhulst, 2003). The most common difficulties encountered in early childhood are typically categorised as externalising problems (aggression, oppositional behaviours and hyperactivity) and internalising problems (anxious, depressed and withdrawn behaviours) (Carter et al., 2010; Hawes & Dadds, 2004). Questionnaire scales have been developed to measure these domains, including the well-established Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997). Parents using these scales have been shown to be valuable informants on their young children's behaviour (Hawes & Dadds, 2004).

Exploring the nature of temperament in Indigenous children

Temperament refers to stable, constitutionally based characteristics or behavioural styles that may be evident from birth (see review by Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004). While they have biological roots, they are not set in stone; environments and contexts may promote or discourage the display of particular traits. Research into the underlying elements (structure) of child temperament has consistently identified three broad factors; namely:

- Approach-Sociability (or simply Approach) - the child's degree of comfort when encountering new situations or people;

- Persistence - the child's capacity to self-regulate and see tasks through to completion; and

- Reactivity - how intense and emotionally volatile the child is.

With young children, these dimensions are typically assessed by parents or other primary caregivers who have the best opportunity to observe their child across time and across contexts. Written questionnaires are most often used.

To the extent that it is biologically based, it would make sense for temperament structure to be culturally invariant, such that the same dimensions are relevant for describing temperament across cultures. Indeed, cross-cultural comparisons have provided evidence of the same temperament structure for children from the United States, Australia, Europe and Asia (Bates & Pettit, 2007; Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1999). However, the existence of the same dimensions does not mean that children in different cultures necessarily exhibit these traits to the same degree. Given that temperament can be influenced by the environment, it might in fact be expected that children from some cultures would have "more" of a specific trait than those from other cultures. To date, research that has assessed the same dimensions across cultures has generally observed minimal if any differences, with similar proportions of children from different backgrounds being shy and sociable, emotionally reactive and calm, and persistent and non-persistent (Putnam, Sanson, & Rothbart, 2002; Russell, Hart, Robinson, & Olsen, 2003).

The nature of temperament in Indigenous children in Australia has not previously been investigated. Hence, the first aim of this study was to investigate whether the same dimensions of child temperament found in other cultures could be identified in Indigenous children, as well as whether Indigenous and non-Indigenous children showed similar levels of these traits. Given the biological basis and observed cultural invariance of temperament, the same dimensions of Approach, Persistence and Reactivity were expected to emerge for Indigenous children as for non-Indigenous children. Indigenous and non-Indigenous children were also expected to have generally similar scores on the three traits.

The role of temperament and parenting in psychosocial adjustment

Intrinsic child characteristics such as temperament, along with environmental factors such as parenting, have been shown to play contributory roles in the development of childhood behavioural problems. While temperament is, at least in theory, value-neutral (i.e., characteristics are neither "good" nor "bad" within themselves), certain temperamental traits may fit differently with particular environmental demands, cultural norms and beliefs. Traits that may be perceived as difficult or problematic in one environment or culture may be regarded as desirable in another - for example, shyness is viewed more positively and associated with better outcomes in Eastern than in Western cultures (Chen, Rubin, & Sun, 1992).

In Western cultures, certain temperamental traits have been found to be associated with specific emotional and behavioural problems (for reviews, see Bates & Pettit, 2007; Sanson et al., 2004). In general, greater inhibition and shyness has been linked with internalising problems; lower self-regulation or persistence has been observed to be related to externalising problems; and higher emotional reactivity or volatility predicts both kinds of adjustment difficulties.

Parents are also known to be critically important influences on children's wellbeing. Two realms of parenting that have been found to have significant consequences for children's development are parental warmth (the extent to which a parent conveys love, acceptance, emotional availability and enjoyment of their child) (Rapee, 1997) and harsh discipline (the extent to which parenting reflects overt negative feelings - including criticism and rejection - and involves coercive acts and punitive punishment) (Arnold, O'Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993). Low levels of parental warmth have been linked with emotional problems such as anxiety and depression, as well as aggressive, oppositional behaviour (McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007; Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, Lengua, & Group, 2000), while high levels of parental harsh discipline have been implicated in the development of both internalising and externalising problems (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Chang, 2003; Cowan & Cowan, 2002). The match, or "goodness of fit", between parenting style and child temperament (Chess & Thomas, 1989, p. 380) may also be an important factor in predicting emotional or behavioural problems. For example, highly reactive children who receive hostile, harsh parenting may be particularly susceptible to developing problems with aggression (e.g., Morris et al., 2002).

This research has generally been conducted with population-based samples of children from Western countries, and it is not yet known whether more "difficult" child temperament, sub-optimal parenting style or a poor match between the two pose similar risks for Indigenous children from Australia. The second aim addressed in this study was therefore to examine the associations between temperament, parenting and emotional and behavioural adjustment. We hypothesised that similar relationships to those found in other populations would be observed in Indigenous children; specifically, that:

- more unsociable, shy children at 4.5-5.5 years old would have greater risk of internalising (emotional) problems at 5.5-6.5 years;

- more emotionally volatile, reactive children at 4.5-5.5 years old would have greater risk of later internalising problems and externalising (both conduct and inattention/hyperactivity) problems at 5.5-6.5 years;

- less persistent children at 4.5-5.5 years old would have greater risk of externalising problems at 5.5-6.5 years, particularly difficulties with inattention/hyperactivity;

- children whose parents displayed lower levels of warmth at 3.5-4.5 years old would be at greater risk of internalising problems and conduct problems at 5.5-6.5 years; and

- children who received high levels of hostile, harsh discipline at 3.5-4.5 years old would be more vulnerable to both internalising and externalising problems at 5.5-6.5 years.

The possibility that temperament and parenting might interact in their effects on emotional and behavioural adjustment was also considered. We hypothesised that:

- shy, unsociable children who received low levels of parental warmth would be particularly vulnerable to internalising problems;

- emotionally volatile children who received high harsh discipline would be particularly at risk for conduct problems; and

- children with low persistence who received high harsh discipline would be particularly susceptible to problems of inattention/hyperactivity.

LSIC, which has followed the progress of a large group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children since 2008, is a particularly useful dataset for examining the nature and function of temperament in Indigenous children. Significant time and effort has been devoted to ensuring that data is collected in a culturally appropriate manner while still permitting comparisons with data from the broader Australian community (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs [FaHCSIA], 2009). This has involved adapting well-validated questionnaires used in Western populations for use with Indigenous participants, both in terms of wording and modes of administration. While this is appropriate and necessary, it means that methodological issues need to be carefully considered when analysing the data (see Box 1).

There are some measures used by LSIC that are sufficiently similar to those used in LSAC, which follows a large and representative sample of Australian children of comparable ages, to facilitate meaningful comparisons between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. This study therefore includes an exploration of similarities and differences in temperament and socio-emotional adjustment across these groups.

Box 1: Measuring temperament in Indigenous children

One of the challenges of cross-cultural research is ensuring that relevant constructs are measured in a culturally appropriate way while maintaining scientific rigour and allowing for meaningful comparisons across studies and population. As described in the Measures section, temperament was assessed with a shortened version of the STSC, with a change in mode of administration from a written questionnaire to a structured oral interview. Our first task was therefore to conduct a careful examination of the LSIC temperament questionnaire data, rather than assuming that it would operate similarly to other studies.

We started with a detailed look at response distributions for each item, which showed that rescaling was necessary. We then examined a number of possible reasons for the unexpected item distributions.

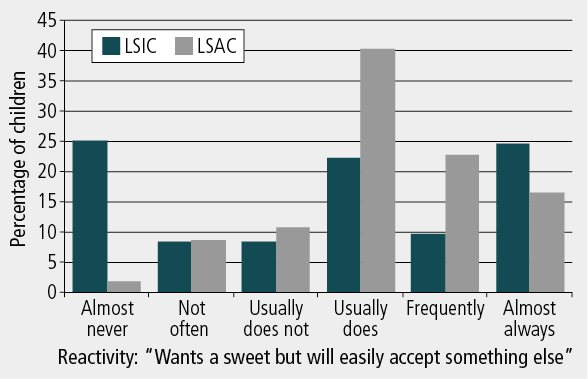

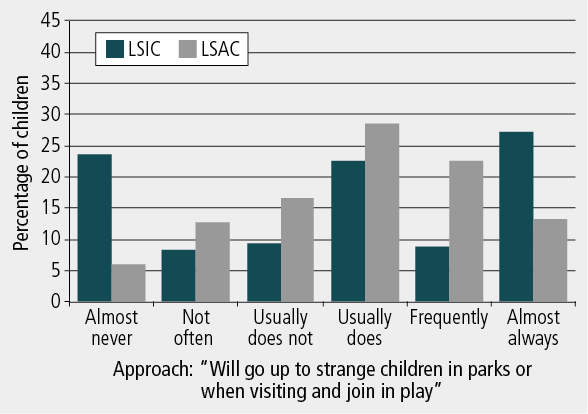

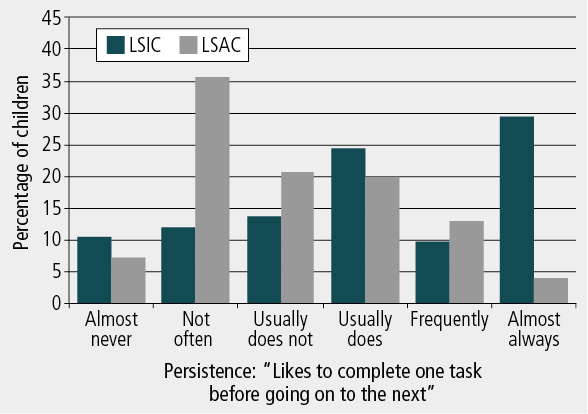

Response distributions

Responses on STSC items are expected to roughly follow a bell-shaped normal curve, with most children rated as around average (ratings of 3 and 4 on the 6-point scale) and few children rated at either extreme (ratings of 1 or 6). This distribution was found in LSAC data. However, responses in the LSIC sample tended to be flatter, and often trimodal, with response peaks at 1 ("almost never"), 4 ("usually does") and 6 ("almost always"). This is illustrated in the three example items in Box Figure 1, with LSAC data for comparison.

This unexpected pattern did not support our prediction that temperament scale responses for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children would be similar, and had ramifications for all subsequent explorations of the psychometric qualities of the STSC. It suggested that averaging item responses across the six response categories to form scores for each dimension was inappropriate for the LSIC cohort, a finding that may have relevance also for other orally presented Likert-style responses in LSIC. Possible reasons for the differences in response distributions are discussed below.

Figure 1: Distribution of responses for LSIC and LSAC on example items from the Approach, Persistence and Reactivity subscales, on the 6-point response scales

Explanations for differences in response distributions

We explored several possible explanations for why LSIC parents responded differently to LSAC parents, with greater endorsement of extremes on the rating scale. First, we considered whether these differences could reflect a serial position effect (Ebbinghaus, 1913), such that LSIC parents better remembered the first or last response options as a result of hearing rather than reading them. However, examination of the response distribution for other measures that were presented orally, such as parenting items, did not show the same response pattern, thus rendering this explanation unlikely.

Second, we wondered whether the results could be due to the questionnaire having less relevance to families with less exposure to mainstream culture. Some parents might have found it difficult to relate to some items, such as whether their child got upset in the supermarket when refused sweets, or whether they played for a long time with a puzzle. We examined this by comparing response distributions across areas with different levels of remoteness, which we regarded as an indicator of exposure to mainstream culture. No differences in response patterns were apparent, rendering this explanation inadequate.

Third, we considered whether these results might reflect unfamiliarity with the concept of rating behaviour on a 6-point Likert scale, especially for those with limited literacy or lower educational attainment, and/or could reflect a cultural preference for "yes/no" or "true/false" options. This was important to examine as research has demonstrated differences in response patterns in other non-Western cultures. For example, South-East Asian and Central American societies have been found to prefer dichotomous answer formats, and this preference is particularly pronounced when individuals have had little formal education (see Flaskerud, 2012 for a review). We found no differences in response pattern as a function of education or income, which suggested that these results could not be attributed to mere familiarity with the questionnaire material or format. However, we could not directly test whether they could be due to cultural difference.

Finally, the extent to which these variations in item ratings may also reflect uncontrolled interviewer processes owing to both the oral presentation of the questions and the collection of the ratings by them remains unknown.

The findings of differences in the original response patterns between LSIC and LSAC illustrate the multiple methodological and conceptual issues that may be encountered in cross-cultural research. In particular, they demonstrate the importance of looking at data carefully when modes of collection and cultural backgrounds of respondents are different, and provide one approach for investigating the equivalence of measurements between cohorts.

It is important to note that, had we simply scored the STSC according to usual procedures (e.g., as in LSAC), the derived means and standard deviations would have suggested that LSIC children were somewhat shier than Indigenous and non-Indigenous LSAC children, as well as more reactive. The alpha coefficients suggested that the scales were somewhat less reliable than in LSAC (Approach: 0.69 in LSIC, versus 0.82 in Indigenous LSAC children and 0.81 in non-Indigenous LSAC children; Persistence: 0.68 in LSIC, versus 0.79 in both LSAC groups; Reactivity: 0.54 in LSIC, versus 0.59 and 0.69 in LSAC Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups respectively). These statistics could have been taken to justify continued use of the scales in the usual way. We believe this would have been inappropriate.

Overview of Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC)

LSIC is a longitudinal study of 1,687 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, conducted by FaHCSIA. An Australian Government initiative, LSIC is governed by the Footprints in Time Steering Committee, chaired by Professor Mick Dodson AM. There has been extensive consultation with Indigenous peoples, communities and organisations, both prior to and throughout the study, around the development of the study's design and content. Since the study's commencement in 2008, LSIC has followed the annual progress of two cohorts of Indigenous children: a birth (B) cohort of infants who were 6-18 months old at the commencement of the study, and a kindergarten (K) cohort of children who were 3.5-4.5 years old.

LSIC used a purposive non-random clustered sampling design, which involved the invitation of eligible families from 11 sites around Australia to participate, following agreement and approval from communities and Elders. Sites were selected to represent the range of socio-economic and community environments where Indigenous children live.

The study investigates similar domains to LSAC, including child temperament, behavioural and emotional adjustment, health, social skills, academic progress and family relationships, as well as broader family functioning, parenting practices and family socio-demographic background. Issues specific to Indigenous children are also assessed. Three waves of data have been collected up to the year 2011 through face-to-face interviews conducted in the home with the primary caregivers (primarily biological mothers), child assessments and teacher and child care provider questionnaires. The current project drew on the first three waves of data from the older K cohort based on the reports of their primary carer, with sample sizes of 719 in Wave 1, 655 in Wave 2 and 589 in Wave 3. At Wave 1, 90% of the primary carers were biological mothers, 3.7% were biological fathers, 3.6% were grandparents, 1.7% were aunts or uncles and 0.9% were adoptive or foster parents.

Overview of Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC)

LSAC follows the development of about 10,000 children and their families from all Australian states and territories (Gray & Smart, 2008). The study commenced in 2004, with two cohorts of children aged 0-1 years (B cohort) and 4-5 years (K cohort) about whom new information is gathered every two years.

LSAC used a clustered, stratified design, with children randomly selected to participate based on their postcodes, and initial contact being through letters from Medicare. This sampling method meant that children in remote areas, especially those who were Indigenous, were less likely to be selected (Hunter, 2008). Thus, while the study is broadly representative of Australian children, the Indigenous children who were recruited into the study were more likely than the general Indigenous population to live in urban areas. This needs to be borne in mind in making comparisons between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous children in LSAC and the Indigenous children of LSIC. It is worth noting that, in 2006, 75% of Indigenous people in Australia lived in non-remote areas (major cities or regional areas) and 25% in remote areas (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2008).

The data used here are from the LSAC B cohort, collected in 2008 in Wave 3 when the children were between 4 and 5 years old. Responses were received from 3,831 families (a response rate of 87%). Of these, 115 (3%) were Indigenous.

Measures

Temperament

Temperament was measured in both LSIC and LSAC with a shortened, 12-item version of the Short Temperament Scale for Children (STSC) (Prior, Sanson, Smart, & Oberklaid, 2000). Four items assessed each of the three temperament dimensions of Approach (e.g., will approach unknown children in parks or when visiting and join in play), Persistence (e.g., likes to complete one task before going on to the next) and Reactivity (e.g., if upset it is hard to comfort him/her). Temperament was measured in the B cohort of LSAC children at Wave 3 when they were 4-5 years old, and in the K cohort of LSIC children at Wave 2, when they were 4.5-5.5 years old.

For LSIC, the standard written administration of the scale (as used in LSAC) was changed to oral administration, with items being read aloud to parents during the face-to-face interview. To better fit this modality, items were changed from statements to questions. Parents then responded orally, using the same 6-point scale as on the written questionnaire, where 1 = "almost never" and 6 = "almost always". Due to the differences in item distributions described in Box 1, responses in both studies were later collapsed into a 3-point scale, such that 1 = "not much", 2 = "sometimes" and 3 = "often". Items on each scale were summed and divided by the number of items responded to, so scores ranged from 1 (reflecting a low level on the temperament trait) to 3 (reflecting a high level).

Parenting

Parenting in LSIC was measured at Wave 1 when the K cohort children were 3.5-4.5 years old, with 10 items that were specifically developed for the study. Items were administered orally during the interview. The items were rated on a 5-point scale, where 1 = "never" and 5 = "always". A factor analysis to identify the underlying constructs tapped by these 10 items suggested that three items measured a construct that was labelled "parental warmth". These items asked how often parents hugged or held their child for no particular reason, went out of their way to show approval of the child, and enjoyed doing things together with them. Another four items tapped a construct that was labelled "harsh discipline", referring to how often parents yelled or shouted when telling off their child, used smacking or time out for misbehaviour, and punished their child for continuing to do something wrong. The remaining three items did not form a coherent factor and were therefore excluded from analyses.

As different measures were used to assess parenting in LSAC, direct comparisons were not possible between LSAC and LSIC and hence are not examined in this study.

Emotional and behavioural adjustment

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to measure emotional and behavioural adjustment in both LSIC and LSAC (with the data used here being collected at age 5.5-6.5 years for LSIC, and 4-5 years for LSAC). The SDQ has been found to be culturally acceptable (Morris et al., 2002) and was used in the Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Study (Zubrick et al., 2005), but it has not yet been validated against clinical diagnosis. In LSIC, the scale was administered orally instead of the usual written form used in LSAC (as for temperament and parenting). Items in the SDQ can be used to derive the subscales of "emotional problems", which targets anxiety, depression and withdrawal behaviours (5 items, e.g., has often seemed unhappy, sad or tearful); "conduct problems", such as lying, stealing, defiance and temper tantrums (5 items; e.g., has often had temper tantrums); and "hyperactivity/inattention", such as significant problems with restlessness, impulsivity and maintaining attention and concentration (5 items; e.g., has been constantly fidgeting or squirming). Response categories were 0 = "not true", 1 = "somewhat true", and 2 = "certainly true". The items were totalled to provide a score out of 10 for each scale. Based on cut-off scores provided by Goodman (2001), scores of 5 and above on emotional problems, 4 and above on conduct problems and 7 and above on hyperactivity/inattention were considered to indicate high risk for clinically significant difficulties.

Findings

Question 1: The nature of temperament in Indigenous 4.5-5.5 year old children

Given that temperament has not previously been assessed in a large sample of young Indigenous children, our first task was to examine the temperament data in detail to ensure its meaningfulness and scientific soundness with this population. As described in Box 1, this revealed a number of unexpected differences compared to other studies including LSAC, reinforcing the importance of careful scrutiny.

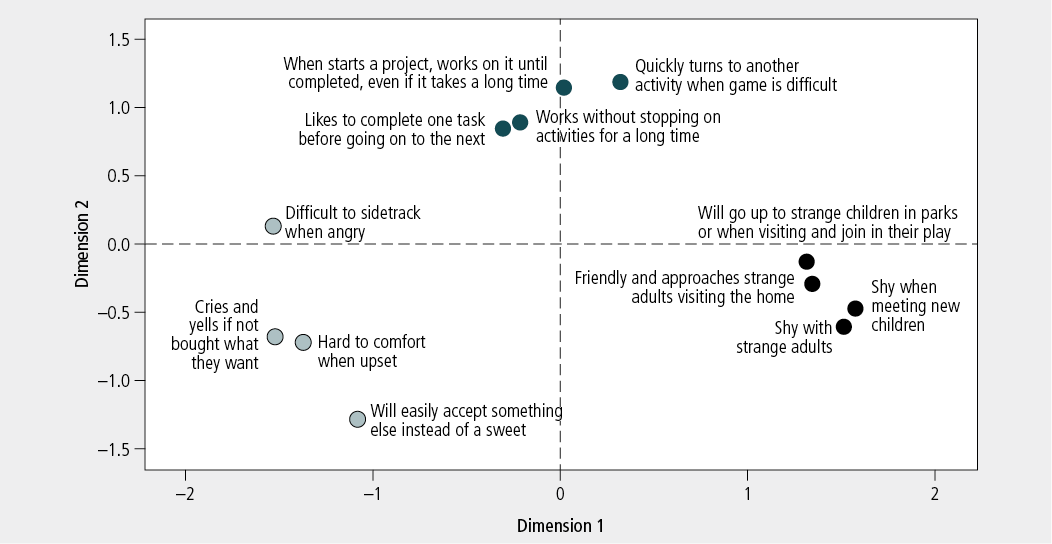

Given the non-normal distribution of the data, it was not appropriate to use factor analysis to explore the structure of temperament in LSIC children.1 Instead, the relationship between temperament items was explored by fitting a Euclidean distance model via multidimensional scaling. Figure 1 provides a graphical depiction of the relationships between the items, by placing them in two-dimensional space. A dimension reduction algorithm calculates locations of the items in space according to the "similarity" or "dissimilarity" of responses among the items. If two items are placed close together, this indicates that parents who reported a high score on one item were likely to report a high score on the other. The results show that individual items measuring Approach are located close together, as are the items measuring Persistence and Reactivity. This suggests that it is appropriate to group items into an Approach scale, a Persistence scale and a Reactivity scale, as expected and similar to other studies such as LSAC.2

Figure 1: Euclidean distance model showing the relationship between items on the Short Temperament Scale for Children (STSC) in LSIC

As discussed in Box 1, the trimodal response distributions for individual temperament items suggested that the 6-point scale was not appropriate for LSIC. We therefore re-scaled responses to create a 3-point scale. Original scale points 1 ("almost never") and 2 ("not often") were merged to create a new point 1 ("not much"); original scale points 3 ("usually does not") and 4 ("usually does") became 2 ("sometimes"), and points 5 ("frequently") and 6 ("almost always") became 3 ("often"). This resulted in a more normal, albeit relatively flat, distribution of responses on the individual items that was sufficient to allow further analysis. In order to allow cross-study comparisons, the same recoding was undertaken with LSAC data.

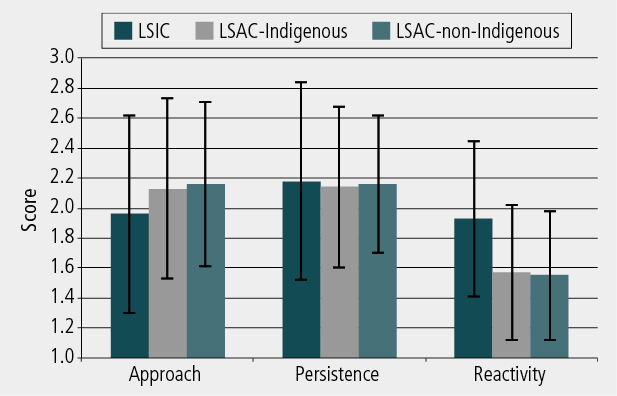

Mean (average) scores and standard deviations on temperament ratings for the LSIC children, Indigenous children from LSAC and non-Indigenous children from LSAC are displayed in Figure 2. Children in all three groups scored around the mid-point on Approach and Persistence, suggesting that the "typical" child in each of these groups showed similar temperament styles, being sometimes sociable and persistent and sometimes not. Children from LSIC, however, were rated slightly higher on Reactivity (M = 1.93, SD = 0.53) than children from LSAC (Indigenous children: M = 1.56, SD = 0.45; non-Indigenous: M = 1.55, SD = 0.43). Indigenous children from LSIC scored around the midpoint on Reactivity, suggesting that they were reactive at times but at other times were more placid. Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children from LSAC were perceived to be a little below the midpoint on Reactivity, indicating that they were usually not reactive. However, as indicated by the overlapping standard deviations, the differences between groups did not appear statistically significant. The larger standard deviations in the LSIC group indicate that there was more variability within this group than the other groups.

Figure 2: Mean ratings on the three temperament scales for LSIC, LSAC Indigenous and LSAC non-Indigenous groups

Note: Bars represent standard deviations.

Question 2: The function of temperament in Indigenous children - how is it associated with later adjustment?

Our second question was how temperament, along with parenting, predicted later adjustment as measured by the SDQ scales of emotional problems, conduct problems and inattention/hyperactivity. The mean level of parent-reported emotional problems at age 5.5-6.5 years was relatively low among children in LSIC (M = 2.42, SD = 2.02) but somewhat higher than that for both non-Indigenous and Indigenous 4-5 year old children from LSAC, who were comparable to each other (LSAC Indigenous: M = 1.51, SD = 1.56; LSAC non-Indigenous: M = 1.41, SD = 1.49). The three groups displayed generally similar mean levels of conduct problems (LSIC: M = 2.41, SD = 1.95; LSAC Indigenous: M = 2.65, SD = 1.97; LSAC non-Indigenous: M = 2.13, SD = 1.77). Children from LSIC and Indigenous children from LSAC were rated as being more inattentive/hyperactive than the non-Indigenous children from LSAC, with difficulties being particularly pronounced in the LSIC cohort (LSIC: M = 4.60, SD = 2.50; LSAC Indigenous: M = 3.90, SD = 1.99; LSAC non-Indigenous M = 3.25, SD = 2.08).

The percentages of children above the cut-offs for risk of clinically significant difficulties in the three groups (see Table 1) reflect the trend for higher levels of reported difficulties in LSIC children, and also to some extent in Indigenous children in LSAC. In LSIC, 15.6% of children were rated as being at high risk of clinically significant emotional problems, compared to 3.5% and 4.6% of Indigenous and non-Indigenous LSAC children respectively. Risk for clinically significant hyperactivity/inattention difficulties was also much greater in LSIC children, with almost a quarter of the cohort (22.5%) falling into this category compared to 12.2% of LSAC Indigenous children and 7% of LSAC non-Indigenous children. The proportion of children at high risk of clinically significant conduct problems was high across all three groups, but particularly in the two Indigenous cohorts (26.8% in LSIC children and 28.7% in LSAC Indigenous children, compared to 20.5% in LSAC non-Indigenous children).

In summary, results on the SDQ suggested higher levels of emotional and behavioural problems in Indigenous children, which were particularly notable in LSIC children. The difference in mode of administration of the SDQ, and the differences in group ages, should be borne in mind in interpreting these results. It should also be noted that by far the majority of children in each of the groups did not show high risk for emotional or behavioural difficulties.

| Percentage of children with clinically significant difficulties | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LSIC (5.5-6.5 years, n = 589) | LSAC Indigenous (4-5 years, n = 114) | LSAC non-Indigenous (4-5 years, n = 3,708) | |

| Emotional problems | 15.6 | 3.5 | 4.6 |

| Conduct problems | 26.8 | 28.7 | 20.5 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | 22.5 | 12.2 | 7.0 |

Parenting in LSIC

Given that parenting is a critical environmental influence on children's outcomes, we included the measures of parental warmth and parental harsh discipline in analyses investigating the role of temperament in predicting later adjustment. The mean score of 4.68 (SD = 0.51) on the parental warmth scale suggested that the "typical" LSIC parent was very affectionate and enjoyed high levels of emotional connectedness with their child. The mean score of 2.74 (SD = 0.81) on harsh discipline suggested that most parents from LSIC did not rely heavily on such forms of parenting.

We used three logistic regression analyses to explore connections between child temperament at age 4.5-5.5 years, parenting at age 3.5-4.5 years, and clinically significant emotional problems, conduct problems and hyperactivity/inattention at age 5.5-6.5 for participants with data on the adjustment outcomes (see Table 2). Gender and family income were entered at the first step to control for their effects, followed by the three temperament dimensions of Approach, Persistence and Reactivity, and two parenting dimensions of warmth and harsh discipline in the second step, and all interactions between temperament and parenting entered in the final step. All predictors except for gender were continuous measures. The Expectation-Maximisation algorithm was used to account for missing data.

The results of logistic regressions are expressed in terms of odds ratios (OR). ORs provide a relative measurement of risk by telling us how much more likely it is that a person experiencing one particular condition (e.g., greater levels of parental harsh discipline) will develop the outcome of interest (e.g., emotional problems), compared to someone with reduced exposure to that condition. When OR = 1, this suggests that the condition does not affect the outcome, while an OR > 1 indicates that the condition is associated with greater risk (higher odds) of the outcome. An OR < 1 denotes a reduced level of risk (lower odds). Confidence intervals (CI) provide an indication of the statistical significance of the OR. When the CI contains the value of "1", which corresponds to the value of "no effect", we cannot be certain that the OR represents a statistically significant altered risk. The results are summarised below. Neither gender nor family income predicted any of the three emotional and behavioural outcomes. In terms of temperament assessed one year previously:

- More outgoing, gregarious LSIC children (at the high end of the Approach scale) appeared to be at approximately half the risk of emotional problems (OR = 0.57, CI = 0.37-0.88, p < 0.05) of their shyer counterparts. The only significant interaction between temperament and parenting showed that these highly sociable children had increased susceptibility to problems of inattention/hyperactivity only when they received high levels of parental harsh discipline (OR = 2.09, CI = 1.16-3.74, p < 0.05). Approach did not predict conduct problems.

- LSIC children who displayed lower persistence were at approximately three times the risk for inattention/hyperactivity problems (OR = 0.32, CI = 0.21-0.48, p < 0.001), and just less than double the risk for conduct problems (OR = 0.66, CI = 0.46-0.95, p < 0.05). Persistence was not associated with emotional problems.

- Highly reactive children's vulnerability to both emotional problems and conduct problems was more than double that of more placid children (OR = 2.61, CI = 1.66-4.10, p < 0.001 and OR = 2.36, CI = 1.62-3.43, p < 0.001 respectively). Highly reactive children also had close to twice the risk of inattention/hyperactivity difficulties (OR = 1.86, CI = 1.24-2.79, p < 0.001).

In terms of the relationship of parenting with problem outcomes two years later:

- Children who received higher levels of parental warmth had almost half the risk for emotional problems (OR = 0.59, CI = 0.36-0.97, p < 0.05) and conduct problems (OR = 0.52, CI = 0.35-0.78, p < 0.01), but warmth had no association with inattention/hyperactivity difficulties.

- In general, parental harsh discipline did not significantly increase risk for emotional and behavioural problems, though, as noted above, higher harsh discipline did increase vulnerability to inattention/hyperactivity for highly outgoing, gregarious children, suggesting that the "fit" between parenting and temperament played a role.

In summary, "temperament" was associated with all indicators of later emotional and behavioural adjustment, while "parental warmth" predicted two areas of difficulties and "harsh discipline" was only predictive for one outcome, when in interaction with temperamental Approach.

| Variable | Logistic regression predicting emotional problems | Logistic regression predicting conduct problems | Logistic regression predicting inattention/hyperactivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | CI (95%) | Adjusted OR | CI (95%) | Adjusted OR | CI (95%) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender (1 = male) | 0.83 | 0.51-1.33 | 1.05 | 0.71-1.55 | 0.72 | 0.47-1.10 |

| Parent household income after tax | 0.94 | 0.82-1.07 | 0.91 | 0.81-1.01 | 0.97 | 0.87-1.9 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Temperament | ||||||

| Approach | 0.57* | 0.37-0.88 | 1.14 | 0.81-1.61 | 1.49* | 1.03-2.17 |

| Persistence | 0.68 | 0.44-1.05 | 0.66* | 0.46-0.95 | 0.32*** | 0.21-0.48 |

| Reactivity | 2.61*** | 1.66-4.10 | 2.36*** | 1.62-3.43 | 1.86* | 1.24-2.79 |

| Parenting | ||||||

| Warmth | 0.59* | 0.36-0.97 | 0.52** | 0.35-.78 | 0.96 | 0.61-1.55 |

| Harsh discipline | 0.87 | 0.62-1.22 | 1.21 | 0.93-1.57 | 1.31 | 0.98-1.75 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Approach X Parental warmth | 1.23 | 0.47-3.18 | 0.51 | 0.22-1.15 | 1.38 | 0.56-3.38 |

| Approach X Parental harsh discipline | 0.96 | 0.55-1.69 | 1.16 | 0.75-1.80 | 1.88* | 1.15-3.10 |

| Persistence X Parental warmth | 1.00 | 0.43-2.35 | 1.32 | 0.61-2.86 | 1.48 | 0.61-3.57 |

| Persistence X Parental harsh discipline | 0.96 | 0.56-1.62 | 0.77 | 0.50-1.18 | 1.12 | 0.68-1.85 |

| Reactivity X Parental warmth | 1.69 | 0.69-4.11 | 1.38 | 0.62-3.03 | 1.42 | 0.60-3.36 |

| Reactivity X Parental harsh discipline | 1.62 | 0.95-2.77 | 1.24 | 0.80-1.93 | 1.05 | 0.64-1.72 |

Notes: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Discussion and implications

LSIC was designed to advance current understanding of how Indigenous children's early years may affect their later development. The knowledge gained from LSIC will be important in guiding policy responses to "close the gap" in the lives of Indigenous children, their families and communities. The current study had a specific interest in temperament and psychosocial adjustment in Indigenous children. It sought to examine both the structure and the nature of temperament as well as the connection between temperament, parenting and later adjustment in the LSIC K cohort. Similar methodologies between LSIC and LSAC allowed comparisons of the temperament and emotional and behavioural adjustment of three groups: Indigenous children from LSIC and Indigenous and non-Indigenous children from LSAC.

Our findings suggest similarities in temperament structure across Indigenous and non-Indigenous children, with the same three dimensions appearing in LSIC as in previous studies with the same instrument. There also appear to be similar average levels of the temperamental traits of Approach and Persistence in LSIC children and both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children in LSAC, while LSIC children demonstrated only slightly higher average levels of Reactivity.

However, examination of the individual item responses suggested that LSIC parents responded to the 6-point rating scale differently to LSAC parents. They were more likely to rate their children as more extreme (at both the "easy" and "difficult" ends of the continuum) on these temperamental traits than LSAC parents. As described in Box 1, we explored a variety of possible reasons for these differences, with no conclusive answers being apparent. Further research is required to determine whether Indigenous children do in fact show more extreme temperament traits, or whether the differences in response patterns reflect something else - perhaps, for example, a cultural preference for "yes/no" options rather than Likert-scale alternatives, particularly when items are administrated orally. The non-normal distribution of item responses required changes in the approach to analysis of these variables. Differences in the nature of parents' responses also mean that interpretations of comparisons with other studies such as LSAC need to be made with care.

There was evidence that Indigenous children, particularly those from LSIC, experienced higher levels of emotional and behavioural problems, paralleling previous findings from the Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Study (Zubrick et al., 2005). There was an age difference of approximately one year between the assessments of emotional and behavioural problems in the two studies. Available evidence suggests considerable stability in these problems over the period from 4 to 6 years old, and certainly no sharp increase over this period (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Luby et al., 2002), so age differences seem unlikely to explain the findings. Once again, the influence of mode of administration needs to be considered in interpreting these findings, as does the conceptual "meaning" of the items to the respondents. It is also possible that the difference in emotional and behavioural problems between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children could reflect demographic differences, such as differences in socio-economic status or parental education. Clearly these issues warrant further investigation. It is also worth reiterating, however, that most LSIC children did not show any signs of difficulties.

Despite it not being possible to make direct comparisons between LSIC and other studies, our findings regarding the contribution of temperament and parenting to later adjustment difficulties are broadly comparable with those of previous studies of non-Indigenous children, such as the Australian Temperament Project and LSAC (Smart & Sanson, 2008). First, there were strong associations between the temperamental trait of approach and later emotional problems, between persistence and both inattentiveness/hyperactivity and conduct problems, and between reactivity and all three types of difficulties, as hypothesised. Similar patterns have been found in previous studies. It therefore appears that temperament affects development in a similar way in Indigenous and non-Indigenous children, as expected. With regard to parenting, findings suggested that Indigenous parents were typically warm towards their children and did not rely heavily on harsh discipline techniques. Lower levels of parental warmth and higher harsh discipline were related to some aspects of emotional and behavioural adjustment, although not all hypothesised associations were found. In particular, the predicted interactions between parenting and temperament were not observed, though an unanticipated interaction between approach and parental harsh discipline was seen. Results were nevertheless comparable to findings from LSAC (Zubrick et al., 2008).

These associations reinforce the importance of individual differences in child temperament in the aetiology of childhood emotional and behavioural problems. The findings therefore emphasise the need for temperament to be taken into account when planning prevention and intervention efforts, and the importance of making support available to parents, particularly if their child has temperamental characteristics that may be difficult to manage. The finding that there is an interaction between harsh discipline and high approachability in increasing a child's risk for hyperactivity/inattention is also a reminder of the importance of parents understanding their child's temperament so that they can match their parenting to their child's needs. Despite most LSIC children being rated as at low risk for adjustment problems, the emergence of significant levels of problems by 5.5-6.5 years of age is a strong signal for the need for better preventive and early intervention efforts.

The current study also highlighted the necessity of examining the basic characteristics of study data carefully before engaging in further analysis, especially when there are differences in sample characteristics and/or modes of data collection from previous research. These differences also complicate comparisons across studies, especially where the cultural background of respondents differs. Moreover, it is a reminder that while measures might be the same across studies, this does not guarantee that they tap identical constructs.

The question of equivalence of measures is a particular challenge for cross-cultural research, where there are often concerns about the validity of measures that have been developed for Western populations for use in other cultures. While it is important for measures to be similar enough to allow meaningful comparisons, it is equally important for measures to be culturally appropriate. It is important to acknowledge that there may be differences in the value placed on particular traits or constructs, and in perceptions about the appropriateness of specific behaviours at particular ages that may affect participants' responses. It is also possible that the scales used to capture responses (e.g., scales with "sometimes" and "often") may have a different meaning for individuals from different cultural groups, and there may be cultural differences in response preferences (e.g., for "yes/no" versus Likert responses). This study's finding of similar functional relationships between temperament and adjustment in LSIC and LSAC, however, does suggest that while parents in the two studies might have responded differently on the original 6-point temperament scales, the three temperament dimensions of Approach, Persistence and Reactivity are in fact similar in meaning and significance across cultural contexts.

As with all longitudinal studies, there has been some attrition in LSIC; however, checks on the temperament and parenting of children with and without SDQ data at Wave 3 revealed no differences on these variables, suggesting that the effect of attrition on the findings of the logistic regressions was small. It should also be noted that all data used in this study was based on parent (generally maternal) report, which raises the question of potential reporter bias. For example, a parent's own personality or current difficulties (such as experiencing a mental health condition) may affect the way that they view their child's traits and behaviours (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1993; Mednick, Hocevar, Baker, & Schulsinger, 1996). It is possible that this may account for some part of the association found between parents' ratings of temperament, their own parenting, and their child's emotional and behavioural problems over three waves of data. However, it is generally accepted that parents have a particular advantage in being able to observe a wide range of their child's behaviour and that parent reports have acceptable validity compared to independent assessments (e.g., Pauli-Pott, Mertesacker, Bade, Haverkock, & Beckmann, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 1998). It is also important to remember that any potential subjectivity in parental perceptions has consequences for children's development given that a parent's view of their child is likely to affect their interactions with the child (Mednick et al., 1996).

In summary, this study suggests that the structure and nature of temperament is similar in Indigenous and non-Indigenous preschool-aged children. Due to the unexpected response distributions to the items in the LSIC Wave 2 temperament scales, it is recommended that these data are not analysed as 6-point scales, but rather condensed to 3-point scales as was done here. Furthermore, the study suggests that equally careful scrutiny is given to all LSIC measures. While most LSIC children show good adjustment, the findings suggest concerning levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties at age 5.5-6.5 years, and show that temperament, and to a lesser extent parenting, have a strong predictive association with them. The nature of these associations suggests that the roles of temperament and parenting are similar in the development of Indigenous children and non-Indigenous children, and point to an unmet need for effective prevention and early intervention efforts.

Endnotes

1 Given the non-normal distribution of the data, we initially explored the structure of temperament in the LSIC sample via confirmatory factor analysis using a weighted least squares estimation. This procedure is generally recommended for non-normal ordinal data. Unfortunately, the data proved unsuitable for modeling in this way, due to the relatively small sample size and evidence of failure to meet the underlying assumption of bivariate normality in some of the item distributions. We therefore decided to explore the relationship between the temperament items via multidimensional scaling, as this type of analysis does not pose restrictions regarding multivariate normality. The Euclidian Distance model was selected as it is the "most natural distance function" (Borg & Groenen, 2005, p. 39).

2 The Euclidean model does not address the question of conceptual equivalence. Therefore it should not be assumed that the three temperament scales have the same meaning in LSIC as in other studies.

References

- Arnold, D. S., O'Leary, S. G., Wolff, L. S., & Acker, M. M. (1993). The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment, 5, 137-144. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.5.2.137.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). Experimental Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2006 (Cat. No. 3238.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS.

- Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2007). Temperament, parenting and socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research (pp. 153-177). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Borg, I., & Groenen, P. F. (Eds.) (2005). Modern multidimensional scaling: Theory and applications. New York: Springer.

- Buchanan, A., Flouri, E., & Ten Brinke, J. (2002). Emotional and behavioural problems in childhood and distress in adult life: Risk and protective factors. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(4), 521-527. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01048.x.

- Campbell, S. B., Shaw, D. S., & Gilliom, M. (2000). Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 467-488. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400003114.

- Carter, A. S., Wagmiller, R. J., Gray, S. A. O., McCarthy, K. J., Horwitz, S. M., & Briggs-Gowan, M. J. (2010). Prevalence of DSM-IV disorder in a representative, healthy birth cohort at school entry: Sociodemographic risks and social adaptation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(7), 686-698. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.018.

- Chang, L., Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & McBride-Chang, C. (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 598-606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598.

- Chen, X., Rubin, K. H., & Sun, Y. (1992). Social reputation and peer relationships in Chinese and Canadian children: A cross-cultural study. Child Development, 63, 1336-1343. doi: 10.2307/1131559.

- Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1989). Issues in the clinical application of temperament. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 377-403). New York: Wiley.

- Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2002). Interventions as tests of family systems theories: marital and family relationships in children's development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 14(4), 731-759. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402004054.

- Deater-Deckard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (1997). Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry, 8, 161-175. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0803_1.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA). (2009). Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children - Key Summary Report from Wave 1. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). On memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Teachers College.

- Fergusson, D. M., Lynskey, M. T., & Horwood, L. J. (1993). The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21(3), 245-269. doi: 10.1007/BF00917534.

- Fischer, M., Rolf, J. E., Hasazi, J. E., & Cummings, L. (1984). Follow-up of a preschool epidemiological sample: Cross-age continuities and predictions of later adjustment with internalizing and externalizing dimensions of behavior. Child Development, 55, 137-150. doi: 10.2307/1129840.

- Flaskerud, J. H. (2012). Cultural bias and Likert-type Scales revisited. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33, 130-132. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.600510.

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581-586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x.

- Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1337-1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015.

- Gray, M., & Smart, D. (2008). Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children is now walking and talking. Family Matters, 79, 5-13.

- Hawes, D. J., & Dadds, M. R. (2004). Australian data and psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38(8), 644-651. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2004.01427.x.

- Hunter, B. (2008). Benchmarking the Indigenous sub-sample of the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Australian Social Policy, 7, 61-84.

- Luby, J. L., Heffelfinger, A. K., Mrakotsky, C., Hessler, M. J., Brown, K., & Hildebrand, T. (2002). Preschool major depressive disorder (MDD): Preliminary validation for developmentally modified DSM-IV criteria. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, pp. 928-937. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00011.

- McLeod, B. D., Weisz, J. R., & Wood, J. J. (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 986-1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001.

- Mednick, B. D., Hocevar, D., Baker, R. L., & Schulsinger, C. (1996). Personality and demographic characteristics of mothers and their ratings of child difficultness. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 19, 121-140. doi: 10.1080/016502596385983.

- Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Sessa, F. M., Avenevoli, S., & Essex, M. J. (2002). Temperamental Vulnerability and Negative Parenting as Interacting Predictors of Child Adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 461-471. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00461.x.

- Pauli-Pott, U., Mertesacker, B., Bade, U., Haverkock, A., & Beckmann, D. (2003). Parental perceptions and infant temperament development. Infant Behavior & Development and Psychopathology, 26, 27-48. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(02)00167-4.

- Power, C., & Hertzman, C. (1997). Social and biological pathways linking early life and adult disease. British Medical Bulletin, 53, 210-221. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011601.

- Priest, N., Mackean, T., Waters, E., Davis, E., & Riggs, E. (2009). Indigenous child health research: a critical analysis of Australian studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 33(1), 55-63. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00339.x.

- Prior, M., Sanson, A., Smart, D., & Oberklaid, F. (2000). Pathways from infancy to adolescence: Australian Temperament Project 1983-2000. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Putnam, S. P., Sanson, A. V., & Rothbart, M. K. (2002). Child temperament and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (ed.), Handbook of parenting (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 255-277). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Rapee, R. M. (1997). Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 47-67. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(96)00040-2.

- Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (1998). Temperament. In W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Social Emotional and Personality Development (5 ed., Vol. 3). New York: Wiley.

- Roza, S. J., Hofstra, M. B., Ende, J. v. d., & Verhulst, F. C. (2003). Stable prediction of mood and anxiety disorders based on behavioral and emotional problems in childhood: A 14-year follow-up during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 2116-2121. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2116.

- Russell, A., Hart, C. H., Robinson, C. C., & Olsen, S. F. (2003). Children's sociable and aggressive behaviour with peers: A comparison of the US and Australia, and contributions of temperament and parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(1), 74-86. doi: 1080/01650250244000038.

- Rutter, M. (1991). Childhood experiences and adult psychosocial functioning. In G. R. Bock & J. Whelan (Series Eds.), The Childhood Environment and Adult Disease (Ciba Foundation Symposium 156, pp. 189-200). Chichester, UK: John Wiley.

- Rutter, M., Kim-Cohen, J., & Maughan, B. (2006). Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 47(3-4), 276-295. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01614.x.

- Sanson, A., Hemphill, S. A., & Smart, D. (2004). Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development, 13(1). doi: 10.1046/j.1467-9507.2004.00261.x.

- Schwartz, C. E., Snidman, N., & Kagan, J. (1999). Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1008-1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017.

- Smart, D., & Sanson, A. (2008). Do Australian children have more problems today than twenty years ago? Family Matters, 79, 50-57.

- Stormshak, E. A., Bierman, K. L., McMahon, R. J., Lengua, L. J., & Group, C. P. P. R. (2000). Parenting practices and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 17-29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3

- Thomson, N., MacRae, A., Burns, J., Brankovich, J., Catto, M., Gray, C., et al. (2012). Overview of Australian Indigenous health status, 2011. Mt Lawley, WA: Australian Indigenous Health InfoNet. Retrieved from <www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/health-facts/overviews>.

- Zubrick, S. R., Silburn, S. R., Lawrence, D. M., Mitrou, F. G., Dalby, R. B., Blair et al. (2005). The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People. Perth: Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research.

- Zubrick, S. R., Smith, G. J., Nicholson, J. M., Sanson, A., Jackiewicz, T. A., & the LSAC Research Consortium (2008). Parenting and families in Australia (Social Policy Research Paper No. 34). Canberra: FaHCSIA.

Little, K., Sanson, A., & Zubrick, S. R. (2012). Do individual differences in temperament matter for Indigenous children? The structure and function of temperament in Footprints in Time. Family Matters, 91, 92-105