From training to practice transformation

Implementing a public health parenting program

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2013

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Parenting is an intensely private journey, both joyful and fraught, and often traversed in the wee dark hours in lonely conditions, or perhaps more dauntingly in the full glare of a shopping centre crowd. But parenting is also critical to many aspects of public health. Longitudinal research such as the Christchurch Health and Development Study, which has followed 1,265 New Zealanders from birth to adulthood, shows that childhood conduct disorder may be the most important determinant of problematic lifelong development - being strongly associated with imprisonment, drug dependence, mental illness, early parenthood, inter-partner violence and suicide (Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2009).

A wealth of evidence shows that the most successful intervention for childhood conduct problems is parent management training that is based on social learning and behaviour modification methods, such as the Triple P: Positive Parenting Program® developed by Professor Matthew Sanders and colleagues at the University of Queensland (Fergusson et al., 2009; Nexus Management Consulting, 2009). While a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Wilson et al. (2012) of Triple P evaluations worldwide has pointed to specific weaknesses in the research design of many of these studies (such as small sample size, selective reporting bias and a focus on short-term effects), this does not discount the evidence for parent management training, but does highlight the importance of continual (but cost-effective) improvements to social research and the need to focus on how evidence-based programs are implemented.

The NSW Government began a public health implementation of Triple P in 2008, which was evaluated with an emphasis on what happens after practitioners are trained in an evidence-based program, and how implementation issues affect the changes it creates for families - in the population and in the practice of working with families (Nexus Management Consulting, 2011).

Going public: Triple P

While Triple P began on a small scale as an individually administered training program for parents of disruptive preschool children (Sanders & Glynn, 1981), it has evolved over the past 25 years into a comprehensive public health model of parenting education. Inspired by examples of large-scale health promotion studies that targeted behaviours such as smoking, sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy diets (Farquhar et al., 1985), Matthew Sanders and colleagues developed an evidence-based system of parenting intervention targeting the whole-of-population level.

Triple P now represents a coordinated system of training and accreditation for practitioners across various fields of health, education, child care, general practice and social welfare. Over 62,000 practitioners have undertaken Triple P training in countries including Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Hong Kong, Canada, United States, England, Scotland, Belgium, The Netherlands, Curacao, Republic of Ireland, Japan, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and Iran, with large-scale implementation taking place in several of these countries (Sanders & Murphy-Brennan, 2010; Sanders et al., 2008).

Triple P includes five different levels of intervention, and the NSW implementation of Triple P offers Level 2 Seminars (three developmental guidance seminars aimed at all parents) and/or Level 4 Groups (a series of eight intensive sessions for parents of children with behavioural difficulties) free of charge to all parents of children aged 3 to 8 years. Triple P forms part of the Families NSW prevention and early intervention efforts, jointly delivered by the NSW Department of Family and Community Services (FaCS), Department of Education and Communities (DEC), and Ministry of Health, in partnership with families, community organisations and local government.

Led by FaCS, the implementation was resourced with $5 million from the NSW Government, over four years, to provide:

- governance via interagency Triple P Working Groups;

- engagement and training of 1,100 practitioners from non-government service providers and government agencies between 2008 and 2010; and

- delivery support to encourage each accredited practitioner to deliver two Level 2 Seminar Series and two Level 4 Group Series each year.

By providing Triple P to as many NSW parents as possible, the program aims to:

- reduce risk factors for poor developmental outcomes in children:

- early onset behavioural and emotional problems in children;

- coercive, harmful and ineffective parenting; and

- parents' emotional distress and conflict.

- increase protective factors for favourable developmental outcomes:

- parental confidence and efficacy;

- positive parenting practices; and

- participation in evidence-based parenting programs.

- build the capacity of communities to support parents through:

- capacity and confidence of service providers; and

- interagency collaboration and referral pathways.

Measuring the value of improved parenting

Nexus Management Consulting was engaged in 2009 to evaluate the changes the NSW implementation of Triple P created for families - in the population and in the practice of working with families. The methods were tri-fold:

- A process evaluation assessed the quantity and quality of the program's outputs - practitioner training and support, and the delivery of seminars and groups to families. Methods included: the analysis of program data on practitioners, courses delivered and attendee numbers and demographics; focus groups and consultations with partner agencies and more than 60 practitioners; and an online survey of over 300 practitioners.

- An outcome evaluation measured the quantity and quality of changes in children's behaviour and parenting practices after parents completed a Triple P course. This aimed to confirm that the NSW implementation was effective and delivered client outcomes in line with implementations elsewhere. Methods included: a non-randomised controlled trial involving 182 families; analysis of pre- and post-intervention outcome data and attendee satisfaction data collected by practitioners; and a telephone survey of 45 parents who had recently completed a course.

- An economic evaluation estimated the costs and benefits of making these changes, and any longer term population impacts. Methods included: analyses of the costs incurred by the head office, regional offices and provider organisations; and a literature review.

This paper gives an overview of the evaluation's key findings, but with a focus on the implementation challenges of achieving population reach with a public health parenting program. Further details of the methods and findings, including of the outcome evaluation, are published in the evaluation summary report (Nexus Management Consulting, 2011).

What was done: How much and how well?

In just over two years, over 1,000 practitioners were trained to deliver Triple P - two-thirds from 250 non-government organisations, and mostly child and family workers, caseworkers or service managers. The rate of accreditation following training was high compared to international standards (86%), nearly all practitioners surveyed felt confident about delivering Triple P, and attendee satisfaction with courses was high.

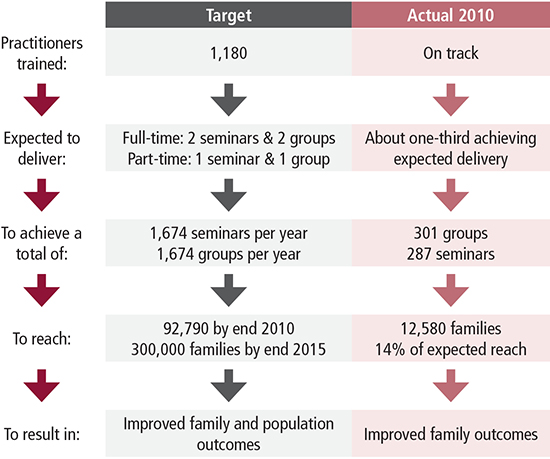

However, only 60% of trained practitioners had started delivering courses to families, and only a third were delivering courses at the expected rate. Thus, in 2010, around 600 Triple P courses were delivered in NSW, less than one-fifth of the targeted 3,348.

Attendee estimates indicated that only about 14% of the target reach was achieved by the end of 2010, and in the absence of broad engagement strategies, families coming to courses were more disadvantaged than the general population, with the children experiencing more emotional and behavioural difficulties.

A mid-term evaluation issues paper in 2010 identified the need for improvements in practitioner and delivery support in order to raise the number of courses being held and to attract more families to attend. As the implementation developed, FaCS boosted efforts to engage, support and ease the workload of practitioners. Initiatives included:

- practitioner peer support groups;

- promotion of co-facilitation;

- a purpose-built scoring application to improve data entry and the use of outcome instruments;

- promotional resources;

- a practitioner website; and

- assistance funding to cover expenses such as audiovisual equipment, child care, refreshments and venue hire.

What changed and for whom?

The outcome evaluation showed that the behaviour and emotional wellbeing of children whose parents attended a Triple P course in NSW improved significantly. The controlled trial used the validated behavioural screening Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1999). Parents answered 25 questions about their children's positive and negative emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems and prosocial behaviour, before and immediately after completing the Triple P Level 2 Seminar Series and six months later. A comparison group of parents who had not attended any parenting courses also completed the survey at the same time intervals.

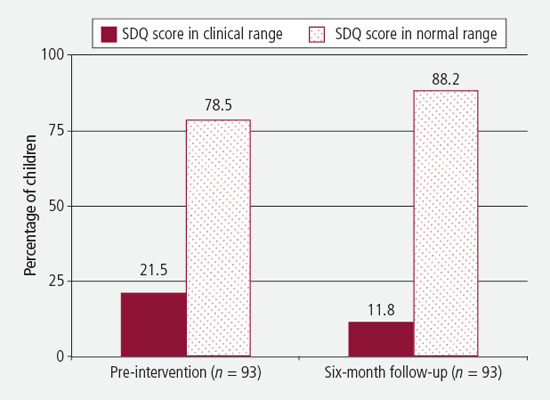

The children (both boys and girls) whose parents went to Triple P seminars showed a significant improvement in their behaviour and emotions six months later, while the children in the no-treatment comparison group did not. There was a net reduction in children with SDQ scores in the clinical range of almost 10 percentage points six months after their parents completed Triple P Level 2 (see Figure 1). That is, of the 93 children in the treatment group with complete data, 20 had an SDQ total problems score of 16 or more (clinical range) before Triple P, while six months later only 11 children did.

Figure 1: SDQ clinical status before Triple P intervention and at six-month follow-up, Triple P Level 2 Seminar Series families

While there were marked differences between the Triple P and comparison groups on their enrolment into the study (the Triple P group was generally more disadvantaged on entry to the study, their children had significantly higher SDQ total problem scores and were more likely to be attending a professional service with regard to their child's behaviour or emotional problems), multivariate analysis adjusting for these differences showed that the rate of improvement was due to participation in Triple P.

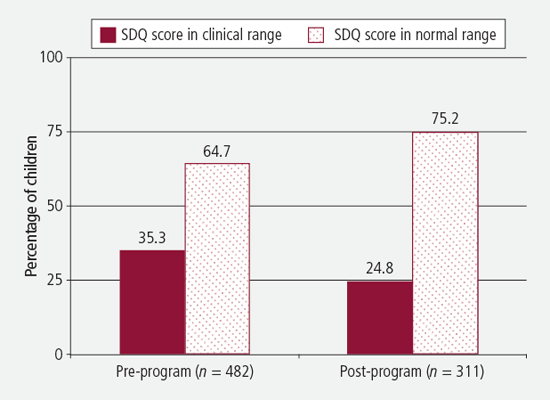

Among those who completed the more intensive eight-week Triple P Level 4 Group Series, analysis of outcome data on parenting behaviour and child behaviour and emotional difficulties also showed significant improvements after attending the sessions. There was a net reduction in the proportion of children with SDQ scores in the clinical range of over 11 percentage points (see Figure 2). That is, of the 482 study children for whom pre-intervention SDQ Total Problems scores were available, there were 170 (or 35%) with scores falling within the clinical range. There were 311 study children with complete SDQ scores available after completing Triple P, and 77 (or 25%) of these had scores within the clinical range, a statistically significant improvement.

Figure 2: SDQ clinical status before Triple P intervention and at completion, Triple P Level 4 Group Series families

These positive changes were reflected in responses to the qualitative telephone surveys of a small sample of Triple P participants, which aimed to complement the evaluation's quantitative data with insights into parents' perceived confidence and reported changes in parenting behaviours. Most parents felt that after participating in Triple P, their child's behaviour had improved (91% of the 45 respondents), they had changed their parenting practices (87%) and were more confident in their parenting (93%).

Practitioners also reported positive effects on their own practice. Practitioners surveyed who were actively delivering Triple P felt it had helped them do their job better, enhancing the services they could offer clients and increasing their confidence in helping families. Almost 90% would recommend Triple P to their colleagues. The practitioner and regional consultations reflected system benefits from Triple P through:

- increased knowledge of other agencies and services;

- the spread of a common language;

- building relationships and trust with clients;

- promoting referrals;

- enhanced peer support;

- co-facilitation and mentoring; and

- sharing resources, such as space, child care and transportation.

The Triple P philosophy, training and resources were commonly cited as being useful tools for strengthening casework and, in some instances, promoting more consistent practices within agencies.

The literature points to significant long-term social benefits and cost savings resulting from Triple P (Access Economics, 2010), and this evaluation's extrapolation of the outcome data suggests that by the end of 2010, the NSW implementation had already moved 1,150 children from the clinical to the non-clinical range of behaviour and emotional difficulties.

At what cost?

The evaluation's costing analysis of the resources contributed by partner agencies and non-government service providers to delivering Triple P shows that in addition to a direct public investment of approximately $5 million, the government leveraged around a further $8 million of value towards the implementation. However with attendance rates low, the cost per child was estimated at a comparatively high $641.

Moreover, the benefits to families, the practices and the service system come at the major cost of increased time pressure among committed practitioners. A quarter of those surveyed noted that their involvement in Triple P had added time pressure to their work, and the evaluation consultations highlighted a key challenge for individual practitioners of balancing the commitment to Triple P with day-to-day work and core commitments.

The implementation challenge

While the implementation of Triple P in NSW successfully trained a multidisciplinary workforce and achieved positive results for the clients it reached, two years in, too few practitioners were delivering courses, only a fraction of the target group families had attended (estimated at 14% of the target families), and those who did attend were not representative of the general NSW population. The implementation was facing two key hurdles in transforming practice to create a population-based public health improvement (captured in Figure 3):

- translating training into delivery of the program to families; and

- achieving reach into the population by engaging a sufficiently broad range of families.

Figure 3: Snapshot of Triple P implementation targets and actual 2010 outcomes

The evaluation report flagged that with the global movement away from restricting parenting interventions to the clinical paradigm, evidence-based programs are developing to strengthen the skills, knowledge and confidence of parents in order to achieve improvements in the health and wellbeing of children at a population level.

The increasing demands being placed on statutory child protection systems across Australia led, in 2009, to the Council of Australian Governments endorsing the application of a public health model to child protection in 2009 (Australian Government, 2009). In NSW, Triple P is cited as being a key part of the universal service system that is helping to reduce child abuse and the numbers of children in out-of-home care (New South Wales Government, 2009).

Shifting parenting support from a clinical intervention to a public health initiative is no mean feat; and while it takes more work to set up, and involves major organisational, structural and systemic changes (Sanders & Murphy-Brennan, 2010), it proffers a much greater payoff for the community, and greater health and broader social gains for children and families (Prinz, Sanders, Shapiro, Whitaker, & Lutzker, 2009).

The NSW experience with Triple P illustrates the point made in the literature examining the implementation of human services programs - that to achieve an effect on the population, it is not enough to train practitioners in high-fidelity, effective and efficient evidence-based programs (Shapiro, Prinz, & Sanders, 2010). The "magic" of practice transformation (the transition from good science to better service) happens when evidence-based programs are supported by implementation drivers that back up training with:

- targeted practitioner selection;

- ongoing coaching;

- consultation and support;

- data systems to support decision-making; and

- system interventions, such as the promotion of collaboration and peer support (Fixsen, & Blase, 2009; Gagliardi et al., 2009; Holt, 2009; Li et al., 2009; Ziviani, Darlington, Feeney, & Head, 2010).

The evaluation identified strengths within the NSW Triple P implementation that could be developed to establish the infrastructure needed to support delivery and increase population reach. These five key steps to practice transformation are:

- universal engagement;

- broad and strategic program promotion;

- integrated data collection (program output and client outcome data);

- active central delivery management; and

- concerted and consistent practitioner support at all levels.

Universal engagement

Universal entry points provide a foundation for the broad engagement that is critical to the success of public health programs, and international experience with Triple P emphasises the importance of having an education sector that embraces and funds parenting support in school settings, and health care settings that offer parenting support (Sanders, Prinz, & Shapiro, 2009). While the evaluation found that many practitioners were delivering Triple P in community health settings, fewer than one-fifth were from the NSW Department of Education and Communities. There is scope to broaden engagement strategies beyond the welfare sector, integrate Triple P with transition-to-school programs, promote Triple P internally within the DEC, make direct approaches to principals and parents and citizens committees to promote Triple P, and deliver Triple P in neutral venues such as local government services and libraries.

Program developments following the evaluation have focused on strengthening relationships between the regional offices of NSW Community Services and DEC staff. Increasing numbers of Level 2 Seminars are being delivered to school communities, and efforts are underway to promote Triple P through DEC internal databases, its intranet and the Parents and Citizens Federation's newsletter.

Liaison with local government services is also being stepped up, with a Triple P support and development project in southwest Sydney working with Children's Services managers to organise collaborative Triple P sessions, and local neighbourhood centres providing free venue hire for Triple P courses on the NSW Central Coast.

Promotional material about Triple P courses and their availability was mailed to school counsellors in primary schools and libraries across NSW and to services already funded through Families NSW to deliver universal programs in July 2012.

Broad and strategic promotion

Promotion in the mass media has traditionally been regarded as being critical to attaining population reach, and online campaigns and social media now also lend themselves to broad engagement. Triple P incorporates a proven mass media component (Level 1), but this was not part of the NSW implementation. Narrowly focused engagement strategies focused on the welfare sector likely contributed to the low reach of the implementation, and so the evaluation recommended a mass media campaign to create positive social norms around attending parenting programs and to drive parents and carers to an easily accessible website where they could book into a course. The campaign would need to be supported by targeted public relations campaigns, community service announcements and online advertising.

Families NSW has since improved its website to make it easier for parents to find and register for a Triple P course, and a promotional campaign was developed with online advertising driving traffic to the site. New promotional materials that focus on a "call to action" - encouraging parents to visit the website or call a 1800 number - were distributed in a statewide letterbox drop to over 800,000 households and schools, libraries, community centres, children's services and a range of other stakeholders. Early reports of the number of families registering for a Triple P event using the online search and booking features of the improved website are encouraging.

Integrated data collection

Embedding the application, recording and reporting of input, output and outcome data is a critical element of optimal implementation in most fields, and is also essential for assessing and improving a public health program's ability to meet the two key challenges of delivery and reach. Both the internal FaCS Triple P program database and the scoring application for practitioners to manage client outcome data were not established until more than two years into the implementation, which may have discouraged practitioners from routinely collecting critical program and client outcome data. Around one-fifth of practitioners surveyed did not ask parents to complete demographic instruments or the key outcomes instrument.

The evaluation recommended introducing some incentives to encourage practitioners to collect and record each client's demographic, satisfaction and outcome data, such as delaying payment of assistance funding (for refreshments, venue costs and child care) until after the scoring application is completed for the clients of each registered course. The evaluation also recommended more proactive tracking of each practitioner's course delivery rate in order to increase the number of courses delivered, and an annual survey of practitioners, both of which have been instigated.

Central delivery management

The systems-contextual approach to improving the reach of public health programs emphasises the importance of using organisational and infrastructural supports to overcome individual, organisational, funding and policy barriers to delivery (Sanders & Murphy-Brennan, 2010). Active central delivery management - liaising closely with service provider organisations to reinforce delivery requirements, backed up by systems to track actual delivery - has helped improve delivery and reach of Triple P implementations internationally (Shapiro, Prinz, & Sanders, 2012). The evaluation underlined the need for governance bodies to extend their involvement to the management of program delivery to clients, in an active partnership with service providers and community organisations. This goes beyond the more traditional focus on simply delivering training in an evidence-based program.

Practitioner support and collaboration

Practitioner self-efficacy is associated with higher delivery rates (Turner, Nicholson, & Sanders, 2011). Four levels of support are available for practitioners delivering Triple P in NSW:

- departmental support via assistance funding, practitioner development days and regional coordination projects;

- support from within a practitioner's own organisation and their manager in managing workloads, maintaining self-efficacy and program fidelity; however, the survey and consultations indicated the level of this support was generally low, and that in many cases managers were unaware of the Triple P delivery commitments. The recommendations for more active central delivery management are aimed at improving this support;

- peer support initiatives on a local level, as well as having a practitioner website to promote networking and collaboration. Central support from governance and funding bodies for active peer support groups was recommended to increase practitioner confidence, delivery rates and program fidelity; and

- collaborative delivery, cited by practitioners surveyed as being very helpful for managing the workload involved in delivering Triple P courses, sharing costs, engaging attendees, administering and scoring outcome instruments and, most importantly, sharing learnings and lending confidence. This can be promoted by dedicated coordinator staff (as in the Western Australian implementation) or by active peer support groups.

Peer support groups or networks now operate in most regions across NSW, supported by the practitioners' website. In Sydney's Metro Central region, Parenting Program Coordination Projects funded by Families NSW have been gathering information about barriers and issues faced by practitioners and holding practitioner workshops. The Resourcing Parents website, a project also funded by Families NSW, has had a significant effect on the coordination, collaboration and delivery of parenting programs and has improved access by parents and carers to available programs. This project was originally funded in the Metro Central region and later expanded to Metro West and Metro South West to cover metropolitan Sydney.

Conclusion

As governments seek to work more and more closely with the community sector, and our frontline of service delivery is peopled increasingly by non-government practitioners, the lessons of implementation provide a useful path through the myriad challenges involved.

Like any family-focused public health intervention, the implementation of Triple P in NSW is no small feat. The joint effort is providing seminars and courses to parents across the state free of charge, and engaging an enthusiastic and committed workforce, with a limited budget and across a diffuse system network.

Providing high-quality training in a proven intervention is only the start. A creative and flexible approach to developing implementation drivers and infrastructure is necessary to harness individual and organisational goodwill, to build on the inherent strengths of the effort, and to generate genuine productive partnerships. Training needs to be augmented by promotion and delivery methods that take the intervention to the population (through the media, schools, libraries and community centres), by tracking and measuring implementation data as well as outcome data, and by ongoing vertical and horizontal practitioner support. Implementation drivers like these help transform practice to create a healthier population from our community's richest resource: families.

References

- Access Economics. (2010). Positive family functioning. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Australian Government. (2009). Protecting children is everyone's business: National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020. An initiative of the Council of Australian Governments. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Farquhar, J. W., Fortmann, S. P., Maccoby, N., Haskell, W. L., Williams, P. T., & Flora, J. A. (1985). The Stanford Five-City Project: Design and methods. American Journal of Epidemiology, 122(2), 323-334.

- Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2009). Situational and generalised conduct problems and later life outcomes: Evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 1084-1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02070.x

- Fixsen, D. L., & Blase, K. A. (2009). Implementation: The missing link between research and practice (Implementation Brief No. 1). Chapel Hill, NC: National Implementation Research Network, FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina.

- Gagliardi, A. R., Perrier, L., Webster, F., Leslie, K., Bell, M., Levinson, W. et al. (2009). Exploring mentorship as a strategy to build capacity for knowledge translation research and practice: Protocol for a qualitative study. Implementation Science, 4, 55. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-55

- Goodman, R. (1999). The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. Journal of Child Psychology, and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40, 791-799.

- Holt, L. (2009). Understanding program logic. Melbourne: Department of Human Services, Victoria.

- Li, L. C., Grimshaw, J. M., Nielsen, C., Judd, M., Coyte, P. C., & Graham, I. D. (2009). Evolution of Wenger's concept of community of practice. Implementation Science, 4, 11. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-11

- New South Wales Government. (2009). Keep them safe: A shared approach to child wellbeing 2009-2014. Sydney: Department of Premier and Cabinet.

- Nexus Management Consulting. (2009). Literature review for the evaluation of the Families NSW implementation of Triple P. Sydney: Families NSW.

- Nexus Management Consulting. (2011). Summary report: Evaluation of the implementation of Triple P in NSW. Sydney: Families NSW. Retrieved from <www.families.nsw.gov.au/assets/triplep_eval_report.pdf>.

- Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, D. R. (2009) Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10(1), 1-12.

- Sanders, M. R., & Glynn, T. (1981). Training parents in behavioural self-management: An analysis of generalisation and maintenance. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, 14(3), 223-237.

- Sanders, M. R., & Murphy-Brennan, M. (2010). Creating conditions for success beyond the professional training environment. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 17, 31-35.

- Sanders, M. R., Prinz, R. J., & Shapiro, C. J. (2009). Predicting uptake and utilization of evidence-based parenting interventions with organizational, service-provider and client variables. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36, 133-143.

- Sanders, M. R., Ralph, A., Sofronoff, K., Gardiner, P., Thompson, R., Dwyer, S., & Bidwell, K. (2008). Every family: A population approach to reducing behavioral and emotional problems in children making the transition to school. Journal of Primary Prevention, 29, 197-222.

- Shapiro, C. J., Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2010). Population-based provider engagement in delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions: Challenges and solutions. Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(4), 223-234.

- Shapiro, C. J., Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2012). Facilitators and barriers to implementation of an evidence-based parenting intervention to prevent child maltreatment: The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 86-95. doi: 10.1177/1077559511424774

- Turner, K. M., Nicholson, J. M., & Sanders, M. R. (2011). The role of practitioner self-efficacy, training, program and workplace factors on the implementation of an evidence-based parenting intervention in primary care. Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(2), 95-112.

- Wilson, P., Rush, R., Hussey, S., Puckering, C., Sim, F., Allely, C. S. et al. (2012). How evidence-based is an "evidence-based parenting program"? A PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis of Triple P. BMC Medicine, 10, 130. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-130

- Ziviani, J., Darlington, Y., Feeney, R., & Head, B. (2010). From policy to practice: A program logic approach to describing the implementation of early intervention services for children with physical disability. Evaluation and Program Planning, 34, 60-68.

Gaven, S., & Schorer, J. (2013). From training to practice transformation Implementing a public health parenting program: Implementing a public health parenting program, Family Matters, 93, 50-57.