Attitudes to post-separation care arrangements in the face of current parental violence

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Determining appropriate post-separation parenting arrangements in cases of alleged or proven family violence is an ongoing issue. One of the factors involved in this difficult area of decision-making is community attitudes to family violence. This article examines public attitudes to child contact or shared care in cases of parent violence towards the other parent, drawing on data from the Australian Survey of Social Attitudes. The survey reveals that a significant proportion of the community appear willing to endorse continued parenting arrangements in the face of family violence, suggesting that some individuals do not see this violence as an obstacle to a perceived need for children to continue to have both parents in their lives. The article then considers these attitudes in light of evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families (LSSF) - a large-scale study conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The issue of appropriate post-separation parenting arrangements in cases of alleged, acknowledged or proven violence in the spousal relationship continues to exercise the minds of judicial officers, legal and social science practitioners, researchers, advocates and, of course, family members themselves - including the children. Among the many variables at play in this difficult area of decision-making are community attitudes to family violence.

Community attitudes have been surveyed with a view to (among other things), providing baseline data against which future changes might be measured.1 In this article, we report on responses to questions about the appropriateness of three particular care-time parenting arrangements in situations in which a parent is currently "threatening or violent towards the other parent after separation". Clearly for each individual, such responses are likely to be informed by a number of variables that could only be known via further, more detailed, investigation. However, our working hypothesis at this stage is that the responses reported in this article are likely to be a reasonable proxy for attitudes towards family violence itself.

We provide a detailed analysis of the responses to questions about the three care-time arrangements. We then place these responses within the context of results from the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families (LSSF), conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS). This large-scale study of parents who separated after the 2006 family law reforms, sought information at three points in time on a range of issues, including whether or not violence had been reported before or during the separation, the current status of the parental relationship, the parenting arrangements currently in place, and how parents rated the wellbeing of their children.2

In light of data from the present study and from the LSSF, we reflect further on post-separation parenting arrangements in the face of present threats and violence. We conclude by suggesting the need for high-quality data capable of providing better understandings of the mindsets of respondents, especially those who indicate that parenting arrangements are appropriate even when threats and violence are a present reality.

Sample and method

The data used here are from participants in the Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA), conducted in 2012-13.3 Questionnaires were sent by mail in four waves to random samples drawn from the Australian Electoral Roll. In total, 1,588 persons aged 18 years and over (687 men and 858 women) completed the questionnaire.4 This represents a response rate of 34%.

Respondents to the survey were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement with each of the following statements:

Even if one parent is threatening or violent towards the other parent after separation, this parent:

- should be allowed to see the children;

- should be allowed to have the children stay overnight with him/her;

- should be allowed to have shared care (i.e., children spend similar time with each parent).

The response options were: "strongly agree", "agree" "neither agree nor disagree", "disagree", "strongly disagree", and "can't choose". In presenting the results, we refer to the second and fourth of these response options as reflecting "moderate agreement" and "moderate disagreement" respectively. Between 8% and 9% of respondents selected the "can't choose" option for each of these three questions, taken separately, so these responses were excluded in the analyses.5

Views on care arrangements in the face of current parental violence

Table 1 summarises the participants' responses in relation to each of the statements on care arrangements even if there are parental threats or violence for the sample as a whole and for men and women separately. To assist with interpretation, the percentages who reported strong and moderate levels of agreement and disagreement are provided both combined and separately.

| Even if one parent is threatening or violent towards the other parent after separation, this parent … | Men | Women | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Note: The association between responses and gender was tested using chi-square tests: * p < .05; *** p < .001. | |||

| Should be allowed to see the children * | |||

| Total agree | 55.4 | 50.9 | 52.9 |

| Strongly agree | 8.8 | 5.7 | 7.1 |

| Moderately agree | 46.6 | 45.2 | 45.8 |

| Neither agree or disagree | 16.8 | 15.1 | 15.9 |

| Total disagree | 27.8 | 34.2 | 31.3 |

| Disagree | 17.8 | 23.1 | 20.7 |

| Strongly disagree | 10.0 | 11.1 | 10.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Should be allowed to have the children stay overnight with him/her *** | |||

| Total agree | 35.0 | 24.8 | 29.5 |

| Strongly agree | 5.4 | 3.7 | 4.5 |

| Moderately agree | 29.6 | 21.1 | 25.0 |

| Neither agree or disagree | 21.8 | 15.4 | 18.3 |

| Total disagree | 43.2 | 59.8 | 52.3 |

| Disagree | 28.1 | 36.5 | 32.7 |

| Strongly disagree | 15.1 | 23.3 | 19.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Should be allowed to have shared care (i.e., children spend similar time with each parent) *** | |||

| Total agree | 35.0 | 24.7 | 29.4 |

| Strongly agree | 5.7 | 3.3 | 4.4 |

| Moderately agree | 29.3 | 21.4 | 25.0 |

| Neither agree or disagree | 25.4 | 15.3 | 20.0 |

| Total disagree | 39.6 | 60.1 | 50.6 |

| Disagree | 26.6 | 36.3 | 31.8 |

| Strongly disagree | 13.0 | 23.8 | 18.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of respondents | 594-601 | 698-742 | 1,292-1,342 |

While a little over half (53%) of all respondents agreed that a parent who was threatening or violent towards the other parent after separation should be allowed to see their children, fewer than a third agreed that this should include having the children stay overnight (30%) or that shared care time should be allowed (29%).

Respondents most commonly agreed (strongly or otherwise) that parents who had been threatening or violent towards their children's other parent should be allowed to see their children; they most commonly disagreed that under these circumstances parents should be allowed to have their children stay overnight or have a shared care-time arrangement.

Men were more likely than women to agree with each statement, with the gender difference being greater with respect to overnight stays and shared care time than with respect to seeing the children.

Men were also more likely than women to find themselves unable or unwilling to proffer a view (neither agree nor disagree) for each statement. This tendency was most pronounced with respect to the third statement - that even if threatening or violent towards the former partner, the parent should be allowed to have shared care. Specifically, the proportion of men who felt unable to either agree or disagree increased from 17% with respect to seeing the child, to 22% for overnight stays, and to 25% for having shared care time. By contrast, 15% of women selected this response option with respect to each issue.

Strength of views

For each of the three issues, men and women who expressed an opinion tended to select the moderate response option ("agree" or "disagree") rather than the extreme option ("strongly agree" or "strongly disagree"). However, for all except one comparison,6 extreme views were more likely to be expressed by those who disagreed rather than by those who agreed with a proposition. That is, strong disagreement was more common than strong agreement. This was particularly the case for women in relation to their views on the allowance of overnight stays or shared care time. Nearly one in four women expressed strong disagreement with this proposition.

Views by gender

Just over half the men (55%) and women (51%) agreed (strongly or otherwise) that even parents who are threatening or violent towards the other parent should be allowed to see the children, while 28% of men and 34% of women disagreed.

Although both men and women most commonly disagreed that these parents should be allowed to have overnight stays or shared care time, women were considerably more likely than men to express disagreement (60% of women compared to 40-43% of men). In turn, 35% of men and 25% of women agreed with each of these two statements (taken separately).

Concordance of views

Of all six comparisons (covering the views of men and women on each of the three statements), the most concordant of views were expressed by women in relation to parents being allowed to have their children stay overnight or to have shared care time, even if threatening or violent towards the other parent (where 60% disagreed with these statements taken separately), while the most divided responses were provided by men in relation to these same two issues (where 35% of men agreed with these statements and 40-43% disagreed).

Agreement with statements on care arrangements, by age and gender

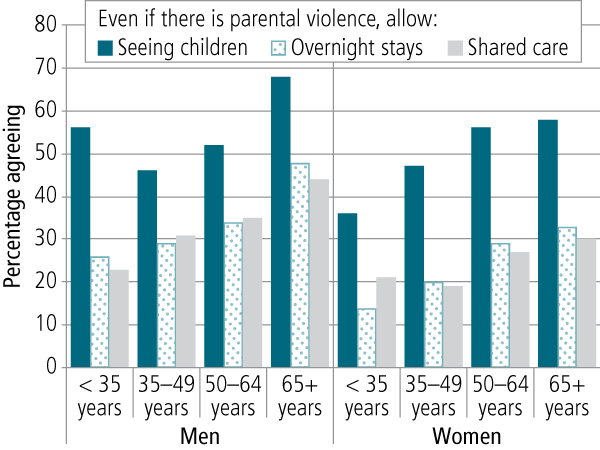

Figure 1 shows the proportions of men and women in four age groups who indicated that they agreed (strongly or otherwise) with each statement. With the exception of women's views regarding shared care time, agreement with each statement was significantly related to age.

Figure 1: Proportions of men and women who agreed with each statement on care arrangements, by age

Note: Sample sizes for the three items: men: < 35 years: n = 70-71, 35-49 years: n = 143-144, 50-64 years: n = 213-215, 65+ years: n = 157-164; women: < 35 years: n = 122-128, 35-49 years: n = 207-212, 50-64 years: n = 229-251, 65+ years: n = 132-147. Separate chi-square tests of the association between responses and age were applied to each set of data for men and women: men: p < .01 for seeing children or overnight stays, and p < .05 for shared care; women: p < .01 for seeing children, and p < .001 for overnight stays, while views on shared care were not significantly related to age.

Men and women in all age groups were considerably more likely to agree with parents being allowed to see their children, even if threatening or violent towards the other parent, than with such parents being allowed to have their children stay overnight or to have shared care time. In most cases, the proportions in each age group (taken separately) who agreed about overnight stays and shared care time were quite similar (differing by only 1-4 percentage points).

In addition, women were, for the most part, less likely than men in the same age group to agree with the various issues. The largest gender difference (20 percentage points: 56% of men, compared with 36% of women) emerged for those under 35 years old regarding threatening or violent parents being allowed to see their children.

For most comparisons, agreement tended to increase with increasing age (i.e., the relationship between agreement and age was typically positive and linear), though the overall relationship was not significant for women.

Agreement with statements on care arrangements, by relationship history and gender

Figure 2 shows the proportions of men and women who agreed with each of the three statements, according to whether they had: (a) never experienced divorce or separation from a cohabiting relationship; (b) had experienced a separation from a cohabiting relationship but had never experienced a divorce; and (c) had experienced a divorce.7 For simplicity, these groups are called "relationship history" groups, with the parents who had experienced a divorce being sometimes referred to as "ever-divorced" parents.

Figure 2: Proportions of men and women who agreed with each statement about care arrangements, by relationship history

Note: Sample sizes for the three items: men: never divorced/separated: n = 393-400, separated/never divorced: n = 56-59, divorced: n = 126-127; women: never divorced/separated: n=446-472, separated/never divorced: n = 80-84, divorced: n = 157-169. Chi-square tests of the association between responses and relationship history were applied to each item for men and women separately: men p < .001 for overnight stays and shared care. Other responses were not significantly related to relationship history.

Once again, higher proportions of men and women agreed with threatening or violent parents being allowed to see their children than with the children staying overnight or having a shared care-time arrangement, with the proportions agreeing with the latter two statements being fairly similar.

The difference in the levels of agreement regarding seeing children as opposed to having overnight stays or shared care time was markedly smaller for ever-divorced men than for all other groups, both male and female.

Although men who had experienced divorce were more likely than the other men to agree with each proposition, they were not significantly more likely than other groups to agree that a threatening or violent parent should be allowed to see their children. On the other hand, ever-divorced men were significantly more likely than the other groups of men to agree with the propositions concerning overnight stays and shared care time. In fact, around half of the ever-divorced men agreed with each of these propositions.

Men in each of the three relationship history groups were more likely than women in the same group to agree with the proposition in question. This was especially the case for ever-divorced respondents concerning children's overnight stays and shared care time (the differences in rates amounted to 23-26 percentage points). By comparison, differences in agreement rates of men and women who had not experienced either form of relationship dissolution were modest.

Women's views on each proposition (taken separately) varied little according to their relationship history experiences.

Evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families

The Longitudinal Study of Separated Families (LSSF) provides an important contextual backdrop against which to consider the difficult question of what, if any, post-separation parenting options are deemed appropriate when family violence is or has been present. The LSSF is a national study of parents with a child under 18 years old at Wave 1 who separated after the 2006 family law reforms and who registered with the Child Support Program in 2007. A total of 10,000 parents were interviewed in Wave 1, some 15 months after their separation. A summary of the sampling and methodology with respect to three waves of this study can be found in Qu, Weston, Moloney, Kaspiew, and Dunstan (2014).

A key finding at Wave 1 was that fewer than half the parents (47% of fathers and 35% of mothers) reported that they had experienced neither emotional abuse nor physical hurt in their relationships. More than a third of all parents (39% of mothers and 36% of fathers) reported that there had experienced emotional abuse (but not physical hurt) prior to or during the separation. Roughly one-quarter of mothers and one-sixth of fathers reported that they had experienced physical hurt prior to separating (Kaspiew et al., 2009, Table 2.2).8

Parents were asked to indicate whether their current relationship with their child's other parent was "friendly", "cooperative", "distant", "fearful" or entailed "lots of conflict". Most fathers and mothers in Wave 1 described their relationship in favourable terms; that is, as either friendly or cooperative. This was especially the case for those who had experienced neither emotional abuse nor physical hurt before or during separation, and applied to a minority who had been physically hurt. Specifically, favourable relationships were reported by: around 85% of fathers and mothers who had not experienced either emotional abuse or physical hurt; 55% of mothers and 50% of fathers who had experienced an emotionally abusive relationship that did not involve physical hurt; and 39% of mothers and 36% of fathers who had been hurt physically.

Clearly negative relationships (i.e., highly conflicted or fearful), on the other hand, were most likely to have been experienced by those who had been hurt physically, and least likely by those whose relationship entailed neither form of violence. With the exception of mothers who had been hurt physically, parents were more likely to describe their relationship as highly conflicted than fearful. For example, where they had been physically hurt, the same proportions (around 20%) of mothers described their relationship as highly conflicted and as fearful, whereas 29% of fathers described their relationship as highly conflicted, but only 11% considered it to be fearful.9

Distant relationships were reported by 22-23% of mothers and 25-27% of fathers who said that they had experienced either physical hurt or emotional abuse without physical hurt (before or during separation), and by 12% of fathers and mothers who had not experienced either form of violence during that period.

These data suggest that a reported absence of violence between parents is strongly correlated with post-separation relationships that are described as friendly or cooperative. At the same time, reported emotional abuse is clearly not incompatible with the development of relationships described as friendly or cooperative. In addition, compared to reports of emotional abuse before and during the separation, reports of physical hurt before separation are somewhat more likely to lead to post-separation relationships being described as highly conflicted and considerably more likely to lead to relationships described as fearful.

Parents who had experienced family violence were also more prone than other parents to report that mental health problems and/or addiction issues were apparent in their relationship prior to separation (see Figure 2.2, p. 31, in Kaspiew et al., 2009). Further analyses of the data suggested that the greater the number of problems experienced before separation (alcohol or drug misuse, mental health issues, emotional abuse, physical hurt), the more likely parents were to indicate a range of other difficulties up to five years after separation.10 Issues reported by parents included highly conflicted or fearful inter-parental relationships, safety concerns for parents themselves and/or their child associated with ongoing contact with the other parent, and diminished personal and child wellbeing (Weston, Hayes, & Qu, 2014). There was evidence that although time could have ameliorative effects, a load of problems often made positive outcomes difficult to achieve.

Discussion

There is evidence that the quality of the parental relationship is a core variable with respect to how well or how poorly children cope with family breakdown. Prior to the 2006 family law reforms, for example, Pryor and Rodgers (2001) reflected on earlier findings from a meta-analysis by Amato and Gilbreth (1999). Both studies reported a link between the post-separation quality of the parental relationship and child wellbeing. These findings were also echoed in LSSF data, which at Waves 1 and 3 found inter-parental relationships to be associated with parental estimates of the wellbeing of their children (see Qu et al., 2014, Figure 8.4).11

Though more difficult to measure, there is also likely to be a link between post-separation quality of parental relationships and parental capacity and willingness to cooperate in organising and sustaining child-appropriate care-time arrangements. From the child's perspective, the capacity of the parents to cooperate over care arrangements would appear to be considerably more important than the precise details of the arrangements themselves (Moloney, 2008; Smyth, 2005). This suggestion is consistent with all three waves of the LSSF data, which revealed weak links, at best, between care-time arrangements and parental assessments of their children's wellbeing (Kaspiew et al., 2009; Qu & Weston, 2010; Qu et al., 2014).

The LSSF data suggest that, for some families at least, there appears to be room for recovery from the dynamics of violence within a post-separation environment. The circumstances in which this occurs - including the nature of the violence experienced; its correlates, such as mental health and addiction problems; and the type and quality of any pre-separation and post-separation services made use of - deserve more detailed exploration into the future.

In the meantime, a limitation of both AuSSA and the LSSF is that while individual constructions of violent acts are likely to influence individual responses to questions linked to child care arrangements, both studies focus not on individuals but on aggregate data. We know that a relatively large number of individuals responding to AuSSA chose to answer the three care arrangement questions definitively. But at this stage, we know little about the reasons for these responses.

We also know that following the 2006 family law reforms, there was evidence of a tendency to prioritise "meaningful relationships" between children and parents over the safety of the child or other family members (see Chisholm, 2009, 2011; Family Law Council, 2009; Kaspiew et al., 2009). This evidence prompted the drafting of the Family Law Legislation Amendment (Family Violence and Other Measures) Act 2011. The aim of these amendments, which came into effect in June 2012, includes improving the family law system's ability to identify family violence and child safety concerns and, in cases in which these aims are in conflict, to support parenting arrangements that give priority to the protection of children, over their right to enjoy a meaningful relationship with each parent.

Considerable effort has gone into supporting the aims of the amendments. The generally raised profile of the extent and consequences of family violence throughout the family law system has been complemented by initiatives such as the development of the AVERT family violence package (Attorney-General's Department, 2010) and the DOORS Detection of Overall Risk Screen Framework (McIntosh & Ralfs, 2012). The AVERT package is designed to be used across the family law system to improve understanding of family violence. DOORS has been designed as a screening tool for identifying and assessing risk from family violence, poor mental health, addiction (the LSSF data demonstrate that these three issues are strongly correlated) and other related concerns.

In addition, having noted that one of the solutions to responding effectively to the problem of family violence is to be found in better professional collaboration, a reference from the Attorney-General to the Family Law Council in October 2014 has asked for advice on:

opportunities for enhancing collaboration and information sharing within the family law system, such as between the family courts and family relationship services … and between the family law system and other relevant support services such as child protection.12

More broadly, the Attorney-General's Department has commissioned AIFS to evaluate the effectiveness of the family violence amendments legislation. This evaluation, is being conducted at a time when awareness of family violence as a "silent epidemic" has been further raised by initiatives such as the appointment of family violence prevention advocate, Rosie Batty, as Australian of the Year and by the Victorian Government's appointment of its Royal Commission Into Family Violence.

The Victorian Royal Commission commenced on 23 February 2015. The background notes accompanying the terms of reference suggest that:

The response to family violence is necessarily complex and requires coordinated and concerted effort across government and the community, including by government departments, courts, police, correctional services, legal services, housing, child protection and family services, schools, health and community organisations.13

In family law settings, an important part of the complexity of the response noted by the Victorian Royal Commission lies in better understanding the conditions under which separated parents adopt a view that care of a child by a perpetrator of violence is acceptable or can be managed. The LSSF data suggest that for at least some parents, separation itself may act as a circuit breaker that permits the re-establishment of a positive relationship capable of supporting good quality care of the children. The data presented in AuSSA, however, tap specific responses to current threats and violence following parental separation. These data suggest that though women are less likely to agree with the proposition, a not inconsiderable number of both men and women appear willing to endorse continued parenting - even overnight parenting - by a perpetrator in the face of present threats and violence towards the other parent.

Violence in any form is an unacceptable means of conducting relationships within the family. More importantly, there is now overwhelming evidence that family violence can leave children and other family members feeling helpless, terrified and traumatised. The survey data reported in this article suggest that some individuals do not see present threats and violence as an obstacle to a perceived need for children to continue have both parents in their lives.14

In light of recent initiatives designed to raise awareness of both the extent and devastating consequences of family violence, it is possible that if conducted today, such a survey might yield differing results.15 Notwithstanding this possibility, there remains a need for sensitively conducted high-quality research aimed at helping us understand the thinking that informs the sort of responses emerging from a study such as this - especially those responses that appear to accept the need for continued parenting arrangements by individuals who are currently threatening or violent towards their former partners.

Endnotes

1 See, for example, the National Survey on Community Attitudes to Violence Against Women 2009, by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (2010).

2 Results form the LSSF are broadly consistent with results from a more recent survey conducted by AIFS using a comparable methodology but based on a different annual cohort of separated parents: the Survey of Recently Separated Parents 2012 (De Maio, Kaspiew, Smart, Dunstan, & Moore, 2013).

3 AuSSA was conducted by the Australian Consortium for Social & Political Research Inc. The questions on which the present article is based formed part of a module on family-related values and attitudes, developed by the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and included in the survey as purchased questions. The survey covered a range of other issues, such as views about gender roles, child care, and intergenerational support.

4 Gender was unknown for 43 respondents.

5 The general patterns of bivariate analysis concerning views on the amount of care-time were similar, regardless of whether the "can't choose" response option was included or excluded.

6 In relation to the proposition regarding seeing the children, virtually the same proportion of men strongly agreed and strongly disagreed. For all other comparisons men and women were at least twice as likely to indicate strong disagreement than strong agreement, although neither of these alternatives were popular for men. Women were 6-7 times more likely to indicate strong disagreement than strong agreement regarding overnight stays and shared care time.

7 The small number of married people who had separated but were not divorced are here classified as "divorced". Although it would have been useful to identify the extent to which views of divorced respondents varied according to whether they had children of the relationship, only 27 men and 44 women had separated/divorced after having children.

8 Significantly too, of those parents who had reported the experience of physical hurt, a clear majority (72% of mothers and 63% of fathers) said that their children had been witnesses to these behaviours.

9 Of those who had been emotionally abused but not physically hurt, 18-20% of mothers and fathers described their current relationship as highly conflicted but only 4% described it as fearful, while 3-4% of those who had not experienced either form of violence said that their relationship was highly conflicted and fewer than 1% considered it to be fearful. These results are taken from Table 2.8 (p. 32) in Kaspiew et al. (2009).

10 Parents were asked to indicate whether mental health problems and drug and alcohol misuse existed in the relationship before separation. Although it was not possible to assess the validity of such assessments, our focus was on parents' perceptions, given the strong influence of perceived circumstances on levels of distress and sense of wellbeing.

11 The question was not asked at Wave 2.

12 See Family Law Council at <www.ag.gov.au/families-and-marriage/family-law-council>.

13 See extract of terms of reference at <www.premier.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/150119-Proposed-Terms-of-Reference2.pdf>.

14 Note that sampling limitations mean the proportions in the general population are unknown.

15 Though sampling issues would mean that direct comparisons would need to be treated with great caution.

References

- Amato, P. R., & Gilbreth, J. G. (1999). Non-resident fathers and children's wellbeing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 557-573.

- Attorney-General's Department. (2010). AVERT family violence: Collaborative responses in the family law system. Canberra: AGD.

- Chisholm, R. (2009). Family courts violence review. Canberra: Attorney-General's Department. Retrieved from <www.ag.gov.au/FamiliesAndMarriage/Families/FamilyViolence/Documents/Family%20Courts%20Violence%20Review.pdf>.

- Chisholm, R. (2011). The family law violence amendment of 2011: A progress report, featuring the debate about family violence orders. Australian Journal of Family Law, 25, 79-95.

- De Maio, J., Kaspiew, R., Smart, D., Dunstan, J., & Moore, S. (2013). Survey of Recently Separated Parents: A study of parents who separated prior to the implementation of the Family Law Amendment (Family Violence and Other Matters) Act 2011. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., Qu, L., & the Family Law Evaluation Team (2009). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Family Law Council. (2009). Improving responses to family violence in the family law system: An advice on the intersection of family violence and family law issues. Canberra: Attorney-General's Department

- McIntosh, J., & Ralfs, C. (2012). The DOORS Detection of Overall Risk Screen Framework. Canberra: Attorney-General's Department.

- Moloney, L. (2008). Dads, family breakdown and the 2006 family law reforms: It's about time - or is it? In Proceedings: Men's Advisory Network Second National Conference (pp. 31-44). Fremantle: Promaco Publishers.

- Pryor, J., & Rodgers, B. (2001). Children in changing families: Life after parental separation. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Qu, L., & Weston, R. (2010). Parenting dynamics after separation: A follow-up study of parents who separated after the 2006 family law reforms. Canberra: Attorney-General's Department.

- Qu, L., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Kaspiew, R., & Dunstan, J. (2014). Post-separation parenting, property and relationship dynamics after five years. Canberra: Attorney-General's Department.

- Smyth, B. (2005). Time to rethink time? The experience of time with children after divorce. Family Matters, 71, 4-10.

- Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. (2010). National Survey on Community Attitudes to Violence Against Women 2009: Changing cultures, changing attitudes. Preventing violence against women: A summary of findings. Carlton, Vic.: VicHealth.

- Weston, R., Hayes, A., & Qu, L. (2014, 1 August). Post-separation journeys of families: Where parents experienced violence/abuse before/during separation and/or where problems relating to mental health or drug/alcohol misuse existed in the relationship pre-separation. Paper presented at 13th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference, Families in a Rapidly Changing World, Melbourne.

Professor Lawrie Moloney is a Senior Research Fellow, Ruth Weston is Assistant Director (Research), and Dr Lixia Qu is a Senior Research Fellow, all at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Moloney, L., Weston, R., & Qu, L. (2015). Attitudes to post-separation care arrangements in the face of current parental violence. Family Matters, 96, 64-71.