Family structure, child outcomes and environmental mediators

An overview of the Development in Diverse Families Study

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

February 2003

Download Research report

Overview

Contemporary research on the adjustment of children growing up in "nontraditional" family forms has raised questions about the capacity of these families to provide for a child's interests. As the dominance of the conventional nuclear family continues to decline, Australian data about diversity within families and between families, and the life chances of children growing up in different family structures, are needed.

Understanding the differing needs of families today is essential for the development of family policies and services that adequately support families in their childrearing tasks. This Research Paper describes a new Institute study that aims to enhance understanding about how family structure relates to the development of children. It examines outcomes for children in different family types and in relation to factors internal and external to the family. The relevant theoretical and empirical literature and the policy context that together form the background to the study, as well as the details of the research approach, are described.

Changing patterns of family structure and formation

There is abundant evidence that Australian families are undergoing rapid change. The diversity of families is evident in the growth of non-traditional family structures. Family structure can be defined in terms of parents' relationships to children in the household (for example, biological or nonbiological), parents' marital status and relationship history (for example, divorced, separated, remarried), the number of parents in the family, and parents' sexual orientation.

Diversification of family types

The 2001 Census counted 4, 936,828 families in Australia. Almost half (47.0 per cent, or 2,321,165 families) were couples with children, and 15.4 per cent were single-parent families (ABS 2002a).(1) Data from the 1997 ABS Family Characteristics Survey showed that 72 per cent of families with dependents aged 0-17 years were intact couple families, while 21 per cent were single-parent families; the remaining 7 per cent lived in stepfamilies(2) or blended families(3) (ABS 1998; see also AIHW 2001: 142-143).

Trends in the proportion of single-parent families in Australia show a marked growth in this family configuration over the past three decades, particularly in the number of women acting as the main parent responsible for both childrearing and income support. Among families with dependent children, the proportion of single parents increased from 9 per cent in 1974 to 15 per cent in 1986 to 19 per cent in 1996 (AIHW 1997). According to the June 2000 Labour Force Survey (ABS 2000b), 83 per cent of single-parent families had a female parent (see also AIHW 2001: 142). The vast majority of children (88 per cent) also live with their mother after parents separate, in either single-parent families (68 per cent) or in step or blended families (20 per cent) (ABS 2002d). Looking to the future, the proportion of single-parent families is projected to increase by between 30 per cent and 60 per cent up to 2021 (ABS 1999b).

These trends are linked to the increase in divorce and separation over the past few decades, and to a lesser extent a rise in births outside marriage. In 1971, before the introduction of the Family Law Act, 2 per cent of people aged 15 and over were divorced. This figure was 6.4 per cent in 1996 and 7.4 per cent in 2001 (ABS 2002a).

Most single parents with dependent children have previously been married (63 per cent separated or divorced, 7 per cent widowed), while 30 per cent had never married (ABS 1998). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the proportion of divorces involving children has fallen over the last 20 years. In 1981, 61 per cent of divorces involved children, declining to 51 per cent of divorces in 2001 (ABS 2002d). However, because the number of divorces has increased, the actual number of children affected by divorce during this period has risen from 49,600 to 53,400. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare also showed that the proportion of children affected by divorce has risen over the decade between 1990 and 1999, from 9.8 per 1,000 children to 11.3 per 1,000 in 1999 (AIHW 2001: 142). McDonald (1995) estimated that one in three marriages would end in divorce, resulting in approximately 10 per cent of children having experienced parental divorce by age 10, and 18 per cent by age 18 years.

The proportion of children born outside of marriage increased from 9 per cent of births in 1971 to 22 per cent in 1990 to 31 per cent in 2001 (ABS 2002c).(4) However, of all ex-nuptial births occurring in 2001, paternity was not acknowledged in only 3.7 per cent of cases, suggesting that most births outside marriage reflected de facto relationships or other forms of fathering (see also Weston, Stanton, Qu and Soriano 2001: 17). Based on the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare's Perinatal Data Collection (birth data from midwives who attend births), Nassar and Sullivan (2001) reported that women in married and de facto relationships accounted for 87.1 per cent of all mothers in Australia in 1999 (excluding New South Wales). In 2001, the median age of women who registered an ex-nuptial birth was 26.2 years, approximately five years younger than the median age of women who registered a nuptial birth (31.0 years) (ABS 2002c).

The proportion of family households consisting of couples and dependent children also decreased from 49.6 per cent in 1996 to 47 per cent in 2001 (ABS 2002a). The decline in the proportion of couple families with dependent children is due to a range of factors including an increase in divorce and singleparent families, childlessness and delays in childbearing, decisions not to have children and the ageing of the population (de Vaus and Wolcott 1997: 3-4). The Australian Bureau of Statistics predicts that the proportion of children in two parent households will further decline over the next 20 years (ABS 1999b).

The chances of entering a stepfamily during childhood are far greater today than in previous decades. The proportion of marriages involving at least one previously married person increased most dramatically in the period from 1972 to 1980 - from 14 per cent of all marriages to 32 per cent of all marriages. The proportion of all marriages involving a remarriage for one or both partners has levelled out at 33 per cent in 2000 (ABS 2001; Weston et al. 2001: 20). There is also some indication that the rate of remarriage (the number of remarriages of men or women, of a certain age, per 1,000 widowed and divorced men and women of the same age) is in decline (ABS 2002d). However, parents in stepfamilies and blended families are more likely to be cohabitating compared with parents in intact families. In 1997, 44 per cent of stepfamilies and 26 per cent of blended families were cohabitating (ABS 1999a).

There is currently no accurate count of the number of gay and lesbian parents in Australia; as Kershaw (2000: 365) notes, 'attempts to establish the total number of lesbians bringing up children are fraught with difficulties'. The most obvious difficulty is that many lesbians, fearing discrimination, hide their sexuality (Pies 1990).

The 1996 Census was the first to recognise same-sex couples if reported. It identified 8,296 same-sex female couples throughout Australia, of whom 1,483 reported living with children. However, the data are not likely to be very reliable because the Census did not seek specific information about sexual orientation (see Mikhailovich, Martin and Lawton 2001: 182). Evidence obtained from clinical encounters and polls conducted within the gay and lesbian community indicates that in the vicinity of 20 per cent of Australian lesbians, gay men and bisexuals have children (VGLRL 2000; LOTL 1999).

Other evidence indicates that a number of lesbian women involved in same-sex relationships want children. Two recent surveys commissioned by a New South Wales lesbian magazine counted the number of lesbians both with children and planning to have children. In 1995, of 732 lesbians surveyed, 20 per cent had children and 14.5 per cent wanted children within the next five years (LOTL 1996: 9). In 1999, 22 per cent of the 386 lesbians surveyed had children, and 20 per cent wanted children (LOTL 2000: 9). A survey of Victorian same-sex couples showed that 41 per cent were hoping to have children, with 63 per cent of those under 30 planning to be parents (VGLRL 2001). Surveys for the Victorian study were distributed by mail-outs to members of the Victorian Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby (11 per cent) and at three gay and lesbian community events (89 per cent). However, in the absence of a population database of lesbians, the number of lesbians currently raising children, and their more general family aspirations, are estimates at best.

The number of children not living with their families of origin also appears to be increasing. The number of children in out-of-home care(5) increased from 1996 onwards in all jurisdictions. At 30 June 2001 there were 18,241 children in outof- home care (includes residential care, relative/kinship care, other home-based care and other forms of accommodation), compared with a total of 13,979 children at 30 June 1996 (AIHW 2002a). Most children (91 per cent) currently living in out-of-home care are living in some type of home-based care arrangement. Between June 1998 and June 2001 the number of children in foster care grew from 8,089 to 9,429 (AIHW 2001: 184; AIHW 2000: 42).

There is also some limited evidence that more relatives, especially grandparents, are assuming residential care of children whose families of origin are unable to care for them. Between June 1998 and June 2001, the number of children in relative/kinship care grew from 4,446 to 6,940 (AIHW 2001: 184; AIHW 2002a). In New South Wales, the number of children in relative/kinship care increased by 78 per cent between 30 June 1996 and 30 June 2000. At present there are no data to indicate the number of grandparents who are assuming residential care of their grandchildren outside the statutory Child Protection System.

Despite increasing numbers of children living away from the homes of their parents, the overall number of non-relative and 'known' child adoptions has been declining since the early 1970s. In the period 1 July 1971 to 30 June 1972 there were 9,798 adoptions, compared with 561 in the 2001-2002 period(6) (AIHW 2002b). Of these adoptions, 52 per cent (294) were intercountry placement adoptions, 29 per cent (160) were 'known' child adoptions, and 19 per cent (107) were local placement adoptions.

Demographic data suggest that family households currently comprise fewer children than several decades ago. In 2001 the average number of babies per woman was 1.73 (1 per cent lower than 2000), which continues a downward trend in the nation's fertility rate that began in the 1960s (ABS 2002c). On these rates, 20 per cent of women currently in their early child bearing years will not have children in their lifetime (Merlo and Rowland 2000). The proportion of couple families with one or no children is also increasing, while the proportion of families with three or more children is declining. The proportion of women with three or more children decreased from 1981 to 2001 for all age groups (ABS 2002c). There are now 2.15 million couple-only families compared with two million couple families with children. Among couple families with dependents, two-child families are becoming the norm (ABS 1998).

Although some estimates are calculated over a lifetime, most of the data are only cross-sectional snapshots of the population. For many children life in a particular family structure is only temporary, and thus population data can underestimate the proportion of children who spend periods of their childhood in non-traditional family structures. Children classified as living in one family arrangement at any one point in time may have experienced any number of family transitions, as well as a host of other changes in the social and economic milieu in which they grow up.

The changing social and economic context

Families and households have presumably been changing in response to the social and economic milieu in which they are embedded, as well as to changes in the nature of relationships within families (Pryor and Rodgers 2001: 28-29; Edgar 2001: 31; Sanson and Lewis 2001: 4). Concomitantly, changes in the internal life of the family are seen as having significant effects on society and the economy.

Perhaps the most significant shift affecting family organisation is the rise in maternal employment. The rise in women's labour force participation was most marked in the period between 1961 and 1981, where the proportion of women of peak childbearing age (24-34) in the labour force leapt from 17.3 per cent to 49 per cent (ABS, various years). This proportion has continued to climb over the past decade, from 66 per cent in August 1990 to 70 per cent in August 2000 (AIHW 2001: 144). At June 2000, both parents (or a single parent) were in the labour force(7) in 49.4 per cent of families where the youngest child was under five years (AIHW 2001).

The rate of maternal employment has a direct bearing on the number of children spending some time in non-maternal child care. In 1999 this applied to 51 per cent of children aged 0-11 years in the week the survey was conducted (AIHW 2001). Although women still assume disproportionate responsibility for looking after children and often report greater work-family stress than men as a consequence, maternal employment has also resulted in greater participation of fathers in childrearing (for example, Gottfried, Gottfried and Bathurst 1995: 144). Graeme Russell, who has researched families in which fathers assumed the main responsibility for child care, argues that male and female sex roles are defined in relation to one another (Russell 1983). It is thus inevitable that fathers are beginning to assume greater responsibility for childrearing at the same time as women extend themselves into educational, occupational and social spheres.

Structural changes in the Australian economy and global market changes have also altered the general environment in which parents enter upon the task of childrearing, through growing pressure on parents to spend longer hours in paid work, more insecure employment, greater job mobility, increasing need for both parents to work, and increasing risk that children will be reared in poverty (Edgar 2001: 21-30).

Young people are also prolonging their education and training and delaying marriage, which has thereby extended the transition to adulthood and the period of dependency upon parents. This is evident in the trend toward later childbearing. Women giving birth when at least 30 years old has increased in recent decades, and this group is also increasingly likely to be first-time mothers (34 per cent in 1999 compared with 27 per cent in 1993) (Weston et al. 2001: 17). Further, as a consequence of Australia's changing population profile, more older adults are in need of care, which can mean parents must juggle caring for elderly parents with care for their own children and grandchildren.

Moreover, some argue that the rise in individualism has undermined commitment to family and children (Popenoe 1993). Increasing education across all socioeconomic levels and women's economic independence has also shifted attitudes about intimate relationships and appropriate family roles and responsibilities. Today, many more couples are negotiating responsibilities for child care and income without reference to previous gender roles and norms (McKeown and Sweeney 2001: 10; Hamilton and Ferry 1997; Wolcott 1995).

The moral, social and economic context of 'westernised' societies has produced, and at the same time reflected, changes to the internal structure of the family. Non-traditional family forms such as single-parent families, step and blended families, same-sex couples with children, and foster families, are becoming an increasingly common feature of Australia's childrearing landscape. Since Australia's future relies on the successful rearing of children in whatever family forms they find themseleves, there is a need to understand the relationship between family structure and child outcomes.

1. It should be noted that a considerable proportion (15 per cent) of the Australian population do not fall within the ABS classification of a household family, because they live alone, in an institution or a group household, or some other form of non-family household (de Vaus and Wolcott 1997: 4).

2. Where one parent is not the natural parent of the child(ren) in the household.

3. Families containing at least one natural child of the couple and one stepchild of one parent.

4. Includes children born in de facto relationships and to single mothers.

5. Out-of-home care is one of a range of services provided to children who are in need of care and protection, and their families (AIHW 2002: 37)

6. Figures include local and inter-country adoptions.

7. The labour force includes people who are employed and people who are not employed but actively looking for work.

Implications of family diversity for children

Although there is scant evidence that 'traditional' family types are normative historically or cross-culturally (Lamb, Sternberg and Thompson 1999; Gilding 2001), reservations have been expressed about whether 'new' household arrangements - single-parent households, stepfamilies, blended families, extended families, gay and lesbian families - are adaptive for children.

Public attitudes toward family diversity

Some make the assumption that children can only be brought up successfully in a two-parent family structure involving a heterosexual relationship. Others take the perspective that children can function well in any family structure, provided certain basic conditions are met.

Researchers have attempted to provide an evidence base to inform this debate by examining the developmental trajectories of children growing up in various family structures. Some findings from this field of research appear to have validated concerns about the wellbeing of such children.

Particular attention has focused on the wellbeing of children growing up in single-parent families. The general conclusion from a large body of data is that children from single-parent families overall fare less well than children from intact two-parent families. Studies have shown that children in singleparent families are apt to have more health problems, poorer social and motor development and more academic problems, and higher probability of both internalising and externalising problems (Underwood and Kamein 1984; Amato and Keith 1991; Dawson 1991; Ferri 1984; Zill 1988 1994; Dunn, Deater-Decard, Pickering and O'Connor 1998: 1083; Human Resources Development Canada 1998: 5). Indeed, there is some evidence that children from single-parent homes continue to experience academic and social adjustment problems even many years after their parents' divorce (Linder, Hagan and Brown 1992).

However, it needs to be noted that most of these data are based on divorced single-parent families, or families involving teenage mothers, rather than women who make a decision to raise a child without a parenting partner. Differences between children growing up in single-parent households and intact couple families also tend to be modest. Many children in single-parent families do just as well as the average child in a two-parent family.

Australian and New Zealand studies that provide data on outcomes for children following divorce or long-term separation of parents tend to mirror findings from overseas research that have shown parental divorce to be a risk factor for a wide range of social and psychological problems in adolescence and adulthood (Rodgers 1998; Fergusson, Diamond, and Horwood 1986; Feehan, McGee, Williams, and Nada-Rada 1995).

The adjustment of children in divorced single-parent families and in stepfamilies is rather similar (Hetherington and Stanley-Hagan 2002: 290). Membership of a stepfamily is also a robust correlate of higher rates of psychopathology in children (Hetherington, Bridges and Insabella 1998; Amato and Keith 1991; Amato 1993).

In contrast to research on single-parent and stepfamilies, research to date has shown that children in same-sex couple families are no more likely to experience psychological disorder than children growing up in more traditional family types (Golombok and Tasker 1994; Green, Mandel, Hotvedt, Gray and Smth 1986; Golombok 1999). However, gay and lesbian-parent families have been little researched. More work is needed in Australia to understand the dynamics of gay and lesbian families and the developmental trajectories of their children.

A family structure effect?

Although family structure is consistently reported as contributing to children's outcomes, there are some key caveats about this body of research that deserves noting.

First, the 'effect size' (the standardised measures indicating the size of differences found between two groups) of differences between family types is generally small in magnitude. In their recent book, Jan Pryor and Bryan Rodgers (2001) summarised findings from individual studies that compared children from intact families and children who do not live with their two biological parents (that is, stepfamilies and single-parent families) in terms of the size of differences found across a broad range of outcomes areas. They concluded that 'children from separated families typically have between one-and-a-half times to double the risk of an adverse outcome compared with children from intact original families' (p. 66). The effect sizes found in Australian divorce studies are similar to those of (predominantly) United States studies (see Rodgers 1998). These effect sizes are considered small because the rates of problem outcomes among children in intact families are generally low (approximately 10 per cent of children experiencing social and emotional problems, and 8 per cent of children demonstrating aggressive or antisocial behaviour are typical findings) (Pryor and Rodgers 2001: 59-61).

The conclusion that effect sizes of differences between different family types are small concurs with findings from a meta-analysis conducted by Amato and Keith (1991), which compared divorced and non-divorced families in the United States (see also Amato 2001). When divorced and non-divorced groups were compared according to eight outcome categories, in three-quarters of cases there were no differences, in 23 per cent there was a significant difference favouring the non-divorced, and in 2 per cent there was a significant difference favouring the divorced. Where significant differences were found, effect sizes were generally small (Burns, Dunlop and Taylor 1997: 136). However, as Burns et al. (1997: 136) note, 'small and often non-significant effects should not be disregarded, because even small disadvantages are serious when they apply to a large group'. Yet, while family transitions place children at slightly increased risk of problem outcomes, 'studies of children's adjustment to divorce and remarriage have shown that relatively few children and adolescents experience enduring problems' (Hetherington and Stanley-Hagan 2002: 309).

Another issue is the striking variability within groups - that is, differences found within groups are often as strong as differences between groups. Many single parents, unmarried couples, stepparents and same-sex parents raise their children successfully, and the majority of children growing up in 'nontraditional' family forms emerge as reasonably competent and well-functioning individuals. As Richards and Schmiege (1993: 277) state in relation to singleparent families: 'For the most part, studies compare single-parent families to two-parent families, thereby ignoring the enormous variability in this increasingly common family form. This lack of attention to family diversity within single-parent families contributes to negative judgements and inhibits the targeting of services to parents and children that most need assistance.'

This then raises the question: is family structure itself the prime determinant of adverse outcomes, or do these problems flow from other sources that tend to cooccur with particular family structures? If (as most research that focuses on the roles of different environmental mediators suggest) other risk factors such as poor parental care, financial strain and parental mental health are closely linked to different types of family structures, then it becomes important to understand how these factors occur and operate in different family structures, and whether family structure has a direct effect on adverse outcomes.

The adequacy of family structure models

The absence of a parent or the loss of a parent are two frameworks for explaining differences in child outcomes among children and young people growing up in non-traditional family structures compared with children living in intact twoparent families.

Parental loss

Although loss of a parent through separation, divorce or death has been associated with child distress in the short term, it is not considered to have deleterious longterm effects (see Rodgers 1998; Pryor and Rodgers 2001). Partial support for this position is provided by evidence that depression in adulthood is just as common in those whose parents divorced while they were young as it is in those whose parents stayed together during their childhood but divorced subsequently (Rodgers 1998).

Comparisons of children who experience parental death compared with parental separation show that parental death does not have the same degree of adverse social and psychological outcomes as divorce (Amato 1993), which suggests that other factors may be more significant in explaining children's poor development. Further, several studies have shown that children suffer significant disadvantage before separation (Elliot and Richards 1991), and that some children may be better off after family change if relationships within the family of origin were hostile, conflictual or abusive (see Amato 1993; Burns 1981).

Parental absence

The absence of a parent is often advanced to explain difficulties in adjustment and functioning among children growing up in single-parent families compared with children who grow up with both biological parents. However, the evidence for poorer outcomes is not consistent among children in single-parent families compared with children in stepfamilies (for example, Adcock and Demo 1994; Amato and Keith 1991), suggesting that the absence of a second parental figure is not the crucial factor.

Parental absence theories often refer to the lack of paternal authority. Although information on the role of fathers as child care providers has increased in recent years, and despite a social shift whereby men are expected to assume more direct responsibility for child care, studies of father-child interactions and their consequences are sparse. However, research is beginning to indicate benefits of positive father involvement, such as engagement, accessibility and responsibility (Lamb, Pleck, Charnov and Levine 1987), for specific types of child outcomes. These effects can be direct, arising from children's experiences and activities with fathers, or may be mediated through the psychological or instrumental support provided to the mother, or through provision of financial assistance. However, more information is required about the nature and consequences of father involvement for children, particularly among traditionally understudied family arrangements.

Given that the sequelae of family change is not adequately explained by parental absence or parental loss frameworks, it is necessary to explore what alternative explanations have to offer.

Family process models

Studies that suggest increases in the risk for child adjustment problems as the result of family membership cannot easily explain why children experience these outcomes. If we are to clarify the mechanisms behind increased rates of adjustment problems reported in single-parent and stepfamilies, these sources of risk must be examined. In order to understand how family structure influences outcomes in Australian children we need to look beyond structural characteristics of families and consider the resources and contexts within which relationships are established and the effective nature of those relationships.

As noted above, family structure itself does not automatically result in negative impacts on child wellbeing. Research that adopts a main effects model, or examines family structure as a direct causal influence on aspects of child functioning, fails to control for crucial intra-familial processes (such as parenting style and monitoring) and extra-familial contexts (such as economic stress and discrimination). Studies that have attempted to disentangle family structure from other factors tend to suggest that there are no simple causal relationships between family structure and child wellbeing.

As Michael Rutter (2002: 324) notes: 'The statistical associations may not derive from any direct reflection of a risk mechanism but rather an association between the postulated risk variable and with some other factor that truly causes the risk . . . For example, for many years the experience of a child being separated from its parents was seen as a major risk for mental health. The findings that this did not apply to happy separations and that the risks associated with parental divorce far exceeded those associated with parental death called that assumption into question (Rutter 1971). Since then, much research with both children (Fergusson, Horwood and Lynsky 1992) and adults (Harris, Brown and Bilfulco 1986) has shown that the major risk mediation derives from poor parental care or family discord rather than from the separation as such.'

Rutter's argument is that family type is a proxy for exposure to psychosocial risks (O'Connor, Dunn, Jenkins, Pickering and Rasbash 2001). That is, certain family types may encounter stressors associated with their family situation, such as compromised quality of parent-child relationships, parental depression and socio-economic adversity. These commonly occurring characteristics of different family environments may chiefly account for the risks to children's wellbeing (Lansford, Ceballo, Abbey and Stewart 2001; Dunn, Deater-Decard and Klebanov 1998; Smith, Brooks-Gunn and O'Connor 1997; Demo and Acock 1996; Forgatch, Patterson and Ray 1995; Amato 1994; Hetherington 1993; Hetherington and Clingempeel 1992; Amato and Keith 1991).

To unpack the relative influence of intra-familial processes and family structure on child wellbeing requires an approach that considers aspects of family functioning in addition to family structure. Attention must also be given to characteristics of the broader environment that indirectly affects child outcomes through their influence on families generally. For example, differences in family processes across family types may well be explained by factors such as social support or financial strain. Care must also be taken to evaluate the effects of individual differences between children and the timing of transitions and reorganisations characteristic of parental divorce and separation.

Hence, the challenge of understanding 'non-traditional' families is best tackled from a multi-dimensional framework, which considers multiple influences on children, including individual child factors, intra-familial processes, and broader familial environments.

A focus on dynamic family processes

Over the past 25 years numerous studies have linked processes within the family to children's social and cognitive competence, pro-social behaviour and internalising and externalising disorders (Wilson and Gottman 2002: 228).

Family systems theory

Family systems theory (Sameroff 1994; Cox and Paley 1997) is a useful frame of reference for understanding the role of within-family processes, or features of the family environment that impact on individual child development.

This theory posits that within each family there is an underlying infrastructure of dyadic relationships (or relationships between two family members) and other sub-system relationships, comprising members of, for example, the same generation (as in parent-parent relationships), the same sex (for example, fathers and sons), or function (parent-child) (Pryor and Rodgers 2001: 46-47). These relationships can each be described, but are also related to the overarching qualities of the family as a whole, which has its own unique and stable interaction pattern (Schoppe, Mangelsdorf and Frosch 2001: 526). The wellbeing of the child, therefore, can be conceived of as dependent upon the functioning of elements of the entire family system (McKeown and Sweeny 2001: 6).

Family factors that consistently emerge in the research as affecting child adjustment include parenting style and discipline methods, family cohesion and support, conflict, sibling relationships, and parental mental health (Deater- Deckard and Dunn 1999).

Parenting and parent-child relationships

Numerous studies have related differences in parenting behaviour and parent-child relationships to developmental differences in children. A range of other potential influences on children, such as individual characteristics of children and parents, economic and life stresses, family functioning and neighbourhood effects work through these parent-child relationships to regulate outcomes for children (Pryor and Rodgers 2001: 252).

Parenting style

Although a range of contextual variables impacts on parenting practices (see below), there is a substantial literature linking several specific dimensions of parenting to child adjustment difficulties. Studies that distinguish child outcomes across family types usually find differences in parenting as well (for example, Amato and Fowler 2002).

A widely accepted model of parenting is Baumrind's categorisation of parenting (Baumrind 1967 1971; Maccoby and Martin 1983; Baumrind 1991). The two dimensions included in this classification system are: acceptance and support (which entails emphasis by parents on warmth and the expression of affection); and control (which can be divided into control based on the use of inductive reasoning and control based on parents' use of power).

Authoritative parenting is characterised by high levels of both acceptance and control; authoritarian parenting is high on control and low on acceptance; permissive parenting is high on warmth and low on control; and neglectful parenting is low on both control and acceptance (Avenevoli, Sessa and Steinberg,1999). In the United States, authoritative parenting has been linked to children's wellbeing in areas of social competence, behaviour and academic performance across different family structures and across different ethnic groups (Steinberg, Mounts, Lamborn and Dornbusch 1991; Hetherington and Stanley- Hagan 2002). Authoritative parenting on the part of the custodial parent or stepparent has also been found to be associated with better child outcomes in single-parent and stepparent households (Anderson, Lider and Bennion 1992; Lidner, Hagan and Brown 1992, but see Fine, Voyandoff and Donnelly 1993).

Ineffective parenting, by contrast, is repeatedly reported as a predictor of poor child outcomes in all types of families, but may be more damaging in singleparent families because of the absence of another parent to compensate for the ineffective parent. At the extreme, harsh and abusive discipline, permissive, laissez-faire parenting, and parental rejection have been shown to produce problem outcomes such as aggressive and criminal behaviour (for example, Lepper 1982).

However, key parenting variables are believed to vary as a function of the age of the child. For example, during infancy interactional processes that are characterised by warmth, consistency and responsivity, or parents' attunement to the child's needs, are seen as important, whereas monitoring, discipline and setting limits are increasingly important as the child moves towards independence.

Parental monitoring and involvement

Studies have found that parental monitoring and supervision are among the most salient practices in terms of disruptive child behaviours (Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber 1986). For example, they have been found to predict antisocial behaviour and substance use (Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber 1984; Chilcoat, Dishion and Anthony 1995).

Parental involvement is also recognised as impacting on child development, and is seen as having two dimensions: parental engagement, or the amount of time a parent engages directly with a child; and parental accessibility, or the time a parent is available to the child.

Parental engagement, measured as the number of times per week that parents engage in certain kinds of activities with their children (such as reading, playing sport and sharing hobbies or games), has been shown to have positive effects on child development (Human Resources Development Canada 1998: 24). Parents' satisfaction with their partner's level of responsibility for routine care duties and housework (division of labour) has also been linked to self-reported levels of marital satisfaction in some studies, particularly across the transition to new parenthood (for example, Shapiro, Gottman and Carrere 2000). Thus, parental involvement may indirectly affect child outcomes by impacting on the parental relationship and its sequelae.

Others have argued that hours spent with children are not as critical as what parents do in their time with children (Lewis, Turnball and Hand 2001).(8) Work hours, for example, show no significant relationship with either parenting or child outcomes (Vander Ven, Cullen, Carrozza and Wright 2001; but see Brooks- Gunn, Han and Waldfogel 2002).(9) When parents engage in specific interactions with their children, such as helping with homework, regular reading and other school-based interactions, children's academic development is enhanced. Further, not all time spent with children is necessarily positive for child outcomes. Parents may need some relief from parenting and caring duties on occasion, and children might gain from time spent away from their parents if alternative care is of high quality.

Parental attitudes, beliefs and values

Multiple variables determine parenting practices, thereby potentially exerting an indirect effect on child outcomes. These include beliefs about parenting and children. Parents from different cultural and social backgrounds are known to differ in their beliefs about children and child development, what tasks children need to master and what a well-socialised child looks like (Bornstein 1991).

Dyadic relationships

Inter-parental relationships: Relationship satisfaction and coparenting

Aspects of the parental relationship or the 'executive subsystem' (Minuchin 1974) have been explored in previous research for their impacts on child adjustment and functioning. These include antagonism between the coparenting partners, the balance of engagement and participation in childrearing tasks, and the overall levels of attunement or consistency between coparents in terms of rules and expectations of child behaviour. These issues may be particularly salient for stepparents (including some same-sex parents) and single parents if a non-resident parent has child contact.

When parents have chronic and unresolved conflict, children are known to suffer particular stress (Brody and Forehand 1990; Buchanan, Maccoby and Dornbusch 1991). A considerable body of literature documents the relation between parental conflict and emotional and behavioural problems in children (Katz and Woodin 2002).

However, while the quality of marital interactions is a good predictor of child development, the mechanisms accounting for this relationship are poorly understood. It is thought that parenting factors may mediate between marital conflict and child dysfunction (Simons, Lorenz, Wu and Conger 1993). Specifically, parental conflict may lead parents to be insensitive to, or withdraw from, their children, or to provide less supervision and monitoring because they are preoccupied with their own relationship issues (Cox, Paley, Payne and Burchinal 1999). Studies have also shown that a parent who is experiencing discord with a partner may exhibit harsh, permissive or inconsistent discipline (Fauber, Forehand, Thomas and Weirson 1990). Parent-child relationships may also be more seriously threatened when the anger or withdrawal engendered by parental conflict is displaced or redirected onto children (Easterbrooks and Emde 1988).

These hypothesised mechanisms linking marital conflict and parent-child relationships are consistent with family systems theories that suggest the nature of one relationship subsystem can 'spill over'(10)into other relationship systems. Children's exposure to marital conflict may also contribute to disturbances in children, particularly if the marital conflict involves physical violence, or if children attempt to intervene in parental disputes.

The impact of marital conflict on child outcomes needs consideration in evaluating the effects of separation on children - that is, whether observed child behaviour problems are due to experiences in previous family settings or from experiences in a new family structure. For example, several researchers have found that child behaviour problems could be found up to 12 years before parents divorced (Amato and Booth 1996).

Another mechanism through which marital conflict is proposed to affect children is by undermining the coparenting subsystem, or the consistency of parental goals, styles, expectations and consequences for children (McHale, Lauretti, Talbot and Pouquette 2002; Floyd, Gilliom and Costigan 1998; Belsky and Hsieh 1998; McHale and Rasmussen 1998; Belsky, Putnam and Crnic 1996).

According to McHale and colleagues (2002: 82), operative elements of coparenting consistency include: agreement about basic elements of effective care; standards for children and socialisation strategies; experiencing affirmation and support from the parenting partner; trust that the partner will enact agreed parenting strategies during their interactions with children; and adherence to agreed 'rules' during, and outside of, the partner's presence.

Erel and Burman (1995) conducted a meta-analysis of studies that relate marital and parent-child relationship quality, and reported a medium effect size (0.46) for the association between measures of marriage and parenting, although the range across studies was between -0.52 and 2.30 (see Grych 2002: 204). It should be noted, however, that the nature of the coparenting alliance can be predicted from a range of other factors in addition to the quality of the parental relationship (McHale and Fivaz-Depeursinge 1999).

Although studies of coparenting are relatively new, research shows striking consistency in the effects of coparental disagreement on child behaviour and development, especially in externalising-spectrum behaviour problems. For example, self-reported differences on various indices of parenting beliefs and childrearing disagreements were linked to child behaviour problems in studies conducted by Block, Block and Morrison (1981); Deal, Halverson and Wampler (1989) and Jouriles, Murphy, Farris and Smith (1991) (as cited in McHale et al. 2002). Other problematic aspects of the coparenting alliance, such as disparagement of the coparent, active undermining, and disconnection, have also been linked to aggression and other behaviour traits in children under the age of five (Belsky, Putnam and Crnic 1996; McHale and Rasmussan 1998).

The conclusion from research on the coparenting alliance is that children growing up in families with greater consistency are more likely to develop security and trust, achieve effective self-regulation, and do better along academic, emotional and social dimensions than children in families in which parents are less consistent (Harrison and Ungerer 1997; van Ijzendoorn, Tavecchio, Stams, Verhoeven and Reiling 1998; McHale et al. 2002). Child representations of the family, which form the basis of child's sense of a secure home base, may also be affected by the coparenting process (Cox and Harter 2002: 172).

Sibling relationships

Sibling relationships may also be important for child development. Although the specific mechanisms are poorly understood, sibling relationships characterised by such things as companionate behaviour, empathy and support can have been related to more favourable outcomes in children, particularly in the face of stress (for example, Anderson, Linder and Bennien 1992; Hetherington et. al. 1999). Alternatively, negative sibling interactions characterised by hostility, rivalry and aggression appear to promote externalising behaviour problems such as aggression in children (Aguilar, O'Brien, August, Aoun, and Hektner 2001). There is some evidence that the relationship between sibling relationship quality and child adjustment is bidirectional, and that the impacts of sibling relationship quality may depend on gender and family type (Hetherington, Henderson and Reiss 1999).

The family as a unit

To understand the development of children it is important to appreciate the functioning of the family as a unit, not just at the individual or dyadic level. Family functioning is a measure of the whole-family unit in the context of whole-family interaction. When a family faces a new situation, such as divorce or remarriage, patterns of interaction and communication within the family are less stable and predictable. Thus differences are expected between families moving through a transitional or adaptational process compared with families that have established patterns for relationships and coping (see Minuchin 2002).

Whole-of-family functioning is considered to have an indirect impact on child development because the quality of interactions within family subsystems (such as parent-child relationships and the co parental relationship) is thought to be governed, at least in part, by the whole-of-family context (for example, Johnson 2001).

Family conflict and family cohesion are two main characteristics of whole-of-family functioning that have been studied for their relationship to child development. In relation to conflict, some studies have documented that level of conflict is a better predictor of children's adjustment than family structure (Forehand, Long, Brody and Fauber 1986; Borrine, Handal, Brown and Searight 1991).

There has also been a proliferation of research on 'family resilience', as a family level variable. However, there is great deal of inconsistency in the way the construct of family resilience is defined and applied in the literature. For example, family resilience has been taken as an outcome (to describe competent family functioning in the face of stress or adversity), as a process (to explain why families living within adverse circumstances manage to function well), and to describe the protective processes and vulnerability processes instrumental in shaping family resilience (Patterson 2002).

Family resilience has also been used to describe family characteristics (such as warmth, closeness and cohesion) linked to outcomes in children and adolescents. For instance, a close emotional tie with an adult family member acts as a protective factor for children in difficult environments, thus intervention at the family level may be critical for increasing resilience in children (Friedman and Chase-Lansdale 2002). Individual children may also display resilience to chronic adversities within the family, such as marital distress, parental psychopathy, poverty and exposure to violence and other forms of abuse.

Parental mental health and parental distress

Parental mental health is an endogenous trait closely linked with many different sources of parental distress. Research has associated particular adverse events and problematic circumstances that may influence parental psychological wellbeing with certain types of families. For example, single parents are thought to suffer stress-related to diminished social support, the burden of child care responsibilities, and financial strain (Hope, Power, and Rodgers 1999). For both men and women, separation and divorce is rated as one of the most distressing life events (Rodgers 1996). Both men and women tend to show recovery in the one to two years after separation, although adverse emotional reactions are persistent for some. According to United States research, divorced and separated people are at least twice as likely to have almost any active disorder compared with those who are single or married (Robins and Regier 1991).

The literature surrounding maternal and dual-earner employment indicates that difficulties in meeting demands of work and family (such as time availability, availability of child care, work schedules, and performing housework), and other work variables (including job flexibility, employment schedules, and hours of work) are a particular form of parental stress in dual-earner couple families (see Gottfried et al. 1995).

Parental distress and parental mental health are known to filter down to affect individual children within families through their effect on the emotional and behavioural functioning of parents. For example, maternal depression is known to involve a range of symptoms that may undermine parenting efficacy, and has been related to more insensitive, negative and punitive parenting in several studies (Krech and Johnson 1992).

8. Notwithstanding the requirement among infants for a consistent presence to form attachment relationships (Belsky and Rovine 1987).

9. Recent analysis of the National Institute for Child and Human Development Early Child care Data suggest that in relation to cognitive outcomes, maternal employment in children's first year of life may have different effects to maternal employment later in a child's life (Brooks-Gunn, Han and Waldfogel 2002; but see Harrison and Ungerer 2002).

10. 'Spill over' has been defined as a process in which the affect expressed in the marriage influences expression of affect in the parent-child relationship.

Environmental influences on child outcomes

As Wilson and Gottman (2002: 228) note: 'Relationships within the family may be the most intimate and influential influence in the lives of individuals.' However, the broader ecology (the economic, social and physical surrounds) regulates the circumstances of the family and, in turn, parents' interactions with their children.

The ecological perspective

An ecological developmental systems perspective extends the family systems framework, and is useful for understanding the ways in which contextual extrafamilial factors can influence child wellbeing (Hetherington and Stanley-Hagan 2002: 289).

Bronfenbrenner (1979) first articulated the importance of interrelationships within and across four levels, or systems within which a child exists. The innermost level is the microsystem, which refers to relationships between the child and the immediate environment; the mesosystem refers to connections among these immediate settings (such as home and school/child care communication); the exosystem involves social settings that affect, but do not contain, the child (such as the parental workplace); and the macrosystem refers to the wider overarching ideologies and policies encompassed in the culture. Features of the larger social ecology in which families live their lives affect child development in direct and indirect ways. Among the important sociocultural factors are socioeconomic status and household income, neighbourhood characteristics, school factors, and the child's peer groups.

Bronfenbrenner's ecological model puts particular emphasis on the complex interrelationships among different parts of the environment, or how the child's immediate family experiences and systems-level family dynamics are linked to the different features of the community and cultural environment, or the larger 'social ecology' in which families are embedded. Bronfenbrenner also noted that the dynamic interaction of characteristics of the person with his or her immediate environment comprises the essential process of developmental change (Lerner 1984).

The risk and resiliency perspective

A risk-and-resiliency framework is also useful for understanding the likelihood of certain outcomes occurring. For example, Amato (1993) has suggested that individual children's situations can best be understood and outcomes predicted if we know what aspects of their lives are stresses and what are resources for them. As well as risk factors having potentially unique effects, there is also the possibility of multiple risk factors having cumulative effects, where their combined impact is multiplicative rather than additive. Children who fare less well often experience the greatest number of adverse conditions and events, rather than any particular circumstance or combination of circumstances (Rutter 1997). Elder and Russell (1996), for example, argue that the total number of negative life events, economic pressure and characteristics of the mother are important for school performance, regardless of family structure (Sanson and Lewis 2001: 7).

The literature on psychosocial adversities in childhood suggests that even after prolonged severe negative experiences, there is a huge variation among children and families in later recovery. This is because certain 'protective' factors may mediate or moderate the effects of risk factors and promote resilience (Rutter 2000; National Crime Prevention 1999: 23; Toumbourou 1999; Kirby and Fraser 1997; Case and Katz 1991). However, research is still required to determine precisely the ways in which interactions among risk and supportive factors explain the patterns of family dynamics and child outcomes (Kaufman and Zigler 1992).

Protective factors are thought to fall into three broad sources of influence: childbased factors, family factors, and sociocultural factors (Pryor and Rodgers 2001: 50). The temperamental characteristic of behavioural inhibition appears protective against antisocial behaviour (Rutter, Giller and Hagell 1998). High levels of warmth in the family, good parent-child relationships and harmonious marital relationships are examples of protective mechanisms operating at the family level. Protective sociocultural factors include high socioeconomic status, neighbourhood resources and a culture that prioritises children's developmental needs.

Social conditions

Empirical research suggests that children may be at risk when their families live in isolation from extended family networks and the surrounding community without adequate supports (see Buchanan and Brinke 1998 for a review). An absence of supportive social networks and local services such as schools and child care can have an effect on parental stress, mood and parenting behaviour, which then directly affects the child's immediate environment (Cumsille and Epstein 1994; Patterson and Forgatch 1990).

Alternatively, social support for families has been shown to reduce family stress and enable maintenance of quality parenting and good family functioning in the face of socioeconomic stressors (Kagan and Weissbourd 1994; Dunst, Trivette, Hamby and Pollack 1990).

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status, often defined in terms of occupation, parental education and family income, is also known to bring about consequences for child wellbeing. An overwhelming number of research studies from the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia have demonstrated a correlation of striking magnitude between child poverty and various measures of child achievement, health and behaviour (Duncan and Brooks-Gunn 2000 1997; Hobcraft 1998; Taylor and McDonald 1998). Both the duration and depth of poverty intensify these effects (McLeod and Shannahan 1996, Smith et al. 1997).

There is mounting evidence that the negative impact of economic disadvantage on children and adolescents significantly derives from effects on the emotions and behaviours of parents or other carers. More specifically, socioeconomic status has been related to parental involvement and particularly parents' ability to provide warmth, structure and control (Conger, Reuter and Conger 2000; Adams 1998; McLoyd 1998; Hoff-Ginsberg and Tardif 1995). Stressors associated with poverty may also have psychological consequences for parents, including low self-esteem, low aspirations and expectations and social isolation, as well as anger and hostility (St Pierre and Layzer 1998).

In a recent comprehensive review of socioeconomic status and child development, Bradley and Corwyn (2002) identified several mediating factors that researchers have specified to explain the processes through which socioeconomic status operates to influence child development. Among these are parent resources and constraints, such as poor nutrition, inability to secure appropriate health care, dilapidated, crowded housing, lack of access to cognitively stimulating materials and experiences, teacher attitudes and expectations and physiologic responses to stress (see also Oliver and Shapiro 1995).

Poverty and lower income are also associated with higher levels of marital stress, dissatisfaction and dissolution (Voydanoff 1990; White and Rogers 2000). Largely as the result of the aforementioned stresses and economic strains, lower socioeconomic status is associated with higher levels of domestic violence (Gelles 1993). Family functioning is also found to vary as a function of socioeconomic status (Bradley and Corwyn 2002).

Children also suffer from living under economic stress because they often live in undesirable or dangerous neighbourhoods with poorly financed or inadequate educational programs and services for children. The quality and quantity of education a child receives is strongly influenced by the level of parental income, which then affects that child's ability to compete effectively in the labour market (Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn and Smith 1998). The quality of school that a child attends may also determine the likelihood of them associating with poorly behaving peers. Parents' occupational status has also been positively related to developmental status in infancy, intelligence, school achievement and social maturity (Gottfried et al. 1995: 149).

Poverty and low socioeconomic status are thought to provide risks for negative outcomes among children growing up in mother-only households in particular (see later).

The community environment

Neighbourhood quality also has a considerable impact on child outcomes (for example, Brooks-Gunn, Duncan and Aber 1997; Chase-Lansdale and Gordon 1996; Burton and Jarrett 2000). Neighbourhood characteristics such as neighbourhood poverty have been shown to influence parents' behaviour. Parents in high crime or dangerous neighbourhoods, for example, tend to exert more parental control (Earls, McGuire and Shay 1994). Studies have found relationships between neighbourhood poverty and elevated rates of crime (Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls 1997), declining social capital (Putnam 2000), greater risk of environmental hazards (Bullard 1990), and higher rates of domestic violence and child abuse (Rank 2000).

The resources available in a local community such as libraries, museums, playgrounds, sports clubs, toy libraries, playgroups, and parks, can also provide opportunities for children's learning and development.

Individual or child-based factors

A wealth of family factors have been associated with children's development. Environmental risks related to particular family compositions also influence children's behaviour and development. However, family circumstances can impinge differently on children within the same family. This is partly because individual differences also constitute a major influence on children's development, and help to shape the way the family environment is experienced.

There is a long list of individual child characteristics that help explain differences among child outcomes. Temperamental characteristics, defined as constitutionally based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart and Ahadi 1994: 64), are thought to emerge early, to be moderately stable, but to be modifiable by experience. Temperament that is characterised by intense negative affect, low adaptability, impulsivity, reactivity and irritability, is predictive of externalising problems, whereas shy, inhibited temperamental characteristics have been associated with internalising disorders (Prior, Sanson, Smart and Oberklaid 2001). Adaptability and sociability have been associated with resilience in children (Werner and Smith 2001).

A child's temperamental characteristics are also thought to impact on the parent, demonstrating bidirectional interactive processes between parents and their children in the socialisation process (Putnam, Sanson and Rothbart 2002). Several studies have found direct associations between temperament and parenting.

It is also speculated that the effect of family structure may vary depending on child gender. For example, father absence may affect boys more than girls because of their need for a male role model, whereas girls may be more threatened by, and thus more likely to reject, the entrance of a stepfather (McLanahan and Teitler 1999). Studies conducted in the United States also suggest that sons exhibit more negative responses to parental divorce than daughters (for example, Sun 2001), although Zaslow (1988; 1989) suggests that discrepant findings can result through methodology, imprecise accounting for demographic factors, type of post-divorce family, nature of the sample, age of the child, and the observational context.

Transitions in family structure

Time since family change

A particular problem for studies comparing original couple families with other families is the confounding effect of length of time in a particular family structure. Studies often compare long-established families with families immediately following a transition, and, unsurprisingly, tend to find poorer outcomes for children in the new family structures (Hetherington and Stanley- Hagan 2002). Such research confounds the stresses of family change (such as diminished financial circumstances, poor accommodation, diminished social support, parental depression, inter-parental conflict, and childrearing stress) with the effects of family structure itself (see Hetherington, Cox, and Cox 1982).

Short-term and long-term effects

Research has demonstrated that the most marked disruptions in individual adjustment and family process occur in the first few years following a change in family structure, with relationships stabilising over time (Hetherington 1991; 1992). Adults and children forming stepfamilies, for example, are likely to experience elevated levels of conflict, parenting difficulties and high levels of psychological stress in the initial phases. Further, according to Hetherington and Stanley-Hagan (2002: 289): 'Achieving a new homeostasis following divorce typically takes two to three years (Hetherington 1989), and it has been estimated that the restabilisation in stepfamilies can take as long as five to seven years . . . '

In divorce studies, reductions in the rate of problems over time among children in post-divorce or post-separation custody also demonstrate that the actual period of change is when children suffer most substantial difficulties (Human Resources Development Canada 1998: 15). Longitudinal studies have also shown that adverse changes in parental functioning following divorce tend to dissipate over time. For example, Chilcoat and Breslau (1996) reported a substantial risk of incident problem drinking associated with divorce within their 3.5-year follow-up period, whereas other studies with longer follow-ups fail to detect such changes (as cited in Power, Rodgers, and Hope 1999: 1484).

However, the review of divorce studies conducted by Pryor and Rodgers (2001: 67) shows that while the magnitude of differences between children from separated and intact families is very modest, poorer outcomes associated with parental separation do persist over time, with even greater divergence between children from separated and in tact families in adulthood on some outcome measures.

To determine whether any adverse effects of family structure persist over time, studies need to conduct separate analyses according to whether families have undergone a transition at an earlier or later stage.

Multiple family changes

Multiple transitions in family structure caused by parents moving in and out of intimate relationships are likely to pose risks for children. The effects of transitions in family structure may be cumulative, in that they appear to influence children's bonds to institutions of social control (family, community, church, school), which heightens risk for behavioural problems (Peterson and Zill 1986; DeGarmo and Forgatch 1999). Parenting and family processes also appear to be diminished in families where parents have had several transitions, which may indicate selection effects - a propensity in parents with frequent partner changes towards poor parenting and lower levels of inter-personal functioning (Barber and Eccles 1992). For example, parenting involvement is negatively associated with the number of transitions a mother has experienced (Capaldi and Patterson 1991).

One Australian study that followed 8,556 pregnant women across four points in time until children were aged five years demonstrated a relationship between family structure changes and risk for behavioural problems (Najman, Behrens, Anderson, Bor, O'Callaghan and Williams 1997). Children who were least likely to have behavioural problems (8.9 per cent to 10.9 per cent) had mothers who never changed partners in the period. Children who were most likely to have problems (15.0 per cent to 17.4 per cent) had mothers who changed partners at least once. Moreover, when mothers' ages and average family income were controlled, the relative risk of child behavioural problems by family instability increased by between 30 per cent and 60 per cent.

Sandefur and Wells (1999, as cited in Sanson and Lewis 2001) also found that the number of changes a child had experienced in their living arrangements affected educational attainment. In respect of outcomes in childhood, higher levels of offending (for example, Fergusson, Horwood and Lynsky 1992), lower levels of happiness (Cockett and Tripp 1994), and poorer educational outcomes (Kurdeck, Fine and Sinclair 1995), have all been associated with multiple family transitions (as cited in Pryor and Rodgers 2001: 69).

Family history

The influence of family transitions is confounded by experiences in a previous family situation. As much evidence is cross-sectional, it is often difficult to know whether child and family functioning observed after a family transition is caused by the transition event itself, the effect of family structure or accompanying risk factors, or whether distress that preceded the family change (for example, violence, abuse and bankruptcy) is accountable. For example, Sun (2001) suggests that post-disruption effects on adolescents can be either totally or largely predicted by pre-disruption factors and changes in family circumstances during the disruption period.

The study from which this conclusion was based involved two waves of a national longitudinal study. It showed that male and female adolescents from families that subsequently dissolved exhibited more academic, psychological, and behavioural problems before the disruption than peers whose parents remain married. Families on the verge of break-up were also characterised by less intimate parent-parent and parent-child relationships, less parental commitment to children's education, and fewer economic and human resources. Thus, some family changes are likely to be associated with a more harmonious, less stressful family situation. In such situations, research suggests that children are very similar to children in intact, low conflict families (Hetherington 1999).

Disentangling the interrelations among individual, familial and contextual factors in different family structures

It is increasingly recognised that outcomes for children are multi-determined, and that linkages among individual, familial and broader contextual factors can be complex. Moreover, relatively little is known about whether the mechanisms that influence child outcomes are different across different family types. As Cox and Harter (2002: 174) suggest in relation to marital and family dynamics: 'There is far too little information on links between adult relationships and parent-child relationships in non-traditional families, including adoptive families, blended families, families headed by gay and lesbian parents, and families in which parents are cohabitating but not legally married.'

Non-traditional families may face unique challenges and difficulties that influence inter-parental, parent-child and family-level dynamics.

From a public policy perspective, research needs to identify any specific factors within the familial and external environment that place children at greater risk for academic, behavioural and psychological problems and their sequelae in different family structures. Interventions can then be focused on the most vulnerable children.

As Lerner, Sparks and McCubbin (1999: 1) point out: 'If the programs that are available to support families . . . are to be maximally useful, they need to be developed to fit the characteristics of the diversity of the families they are intended to help.' (See also Edgar 2001: 33.)

Development in Diverse Families study: Aims and contributions

The Australian Institute of Family Studies has developed a new research project called Development in Diverse Families, which will examine the family life of children growing up in intact, single-parent, step, blended and same-sex parent families, and how their development and wellbeing is thereby affected.

Many studies that have compared children in different family structures are methodologically limited, relying on non-representative and clinical samples or examining mean differences on single outcome variables. Few do more than compare traditional families to one other family type, so relativities among them are unclear. Few studies cover sufficient aspects of family functioning, and in the case of earlier studies, these measures are sometimes entirely absent. Often, critical factors such as the age of parents and children, history of multiple family transitions and the availability of extended family and extra-familial supports are not examined.

Studies have rarely investigated relationships between intra-familial processes (for example, within marital, parent-child and sibling subsystems) in tandem with an appraisal of family functioning at the family-level and other contextual factors that facilitate or impede adjustment and growth. It is thus difficult to determine which children are at the greatest risk of problem outcomes. There is also a dearth of information on Australian children and their families, and there is insufficient information about outcomes early in childhood in particular.

By adopting a multivariate framework that combines family systems and ecological theories (see Hetherington and Stanley-Hagan 2002: 289), the study is designed to provide new information on the conditions, capabilities and relationships of families across different family structures, the associations between several predictor variables and child outcomes, and the relative importance of intra- and extra-familial factors and family structure effects on child wellbeing. This previously unavailable information should highlight the role public policy could play in affecting parents' behaviours and parenting arrangements to the best interests of children.

Family structure and accompanying process and contextual variables may affect children differently depending on their developmental status. The Development in Diverse Families study will examine how family structure affects children between the ages of five and 12 years, the period commonly referred to as middle childhood. Inclusion of children from within a single developmental level has practical advantages for recruitment, assessment and data analysis. As middle childhood is 'a period of intensifying transitions' (Collins, Madsen and Susman-Stillman 2002: 93), it provides an opportunity to study a critical phase in parenting. A child's mastery of developmental challenges during middle childhood, such as the development of autonomy and relationships beyond the family, are also powerfully affected by interpersonal relationships with parents and siblings during this life stage. Family experiences during middle childhood also relate to adaptations that affect wellbeing and competence in and beyond this developmental period. Information on the interactions between family structure and child outcomes during middle childhood can thus inform early intervention and prevention efforts.

The study will include intact nuclear families, in which all children are the biological children of two non-divorced parents. Intact families will be compared with children living in four 'non-traditional' family arrangements. Multiple family types will also be compared with one another, as previous research suggests that intact families may not be an appropriate comparison group for all family types (for example, Patterson 2002: 327).

Single-parent families,(11) stepfamilies, (12) blended families,(13) and same-sex parent families(14) have been selected for inclusion in the Development in Diverse Families study because they are growing family forms, and because some research suggests these family compositions may carry risks for child development. Stepfamilies, blended families and same-sex parent families are currently under-researched, so further work is needed to distinguish what aspects of these families comprise risk, and what aspects may be protective or functional from a child development perspective.

The study will also distinguish between several family subtypes. There will be scope to compare original single-parent families, divorced or separated singleparent families, and single-parent families that result from parental death, as well as father-only families and mother-only families. De facto, stepparent and blended families will also be compared with married families within these broad family categories.

Collection of data on aspects of the family including the inter-parental relationship, parent-child relationships, parental characteristics, family-level functioning and the number and nature of family transitions should offer insight into the complexities of the family system. This study will examine child wellbeing in a number of domains, according to parent reports of children's emotional and behavioural functioning, and parent and teacher reports of children's social and academic functioning. Relationships between these child outcomes, individual child characteristics and the intra- and extra-familial measures above will be explored. Where possible, two parents' perspectives, and in some cases teacher perspectives will be used in evaluating the family and child functioning to guard against biases in using a single perspective.

The study will also aim to recruit representative samples in order to maximise the extent to which generalisations can be made about the larger population from which the sample is drawn. However, for populations such as same sex families it is extremely difficult to develop feasible methods of recruiting representative samples.

The current study is also cross-sectional in design, and cannot draw conclusions about causality and directions of effects. Further, although the measures to be used will be reliable and valid indicators of the constructs being examined, information for the study will rely on parent and teacher report. The limited amount of objective data may therefore have an impact on the results.

The overarching aim of the Development in Diverse Families study is to investigate links between intra-familial processes and child wellbeing within and across family types. More specifically, the study seeks to:

- describe differences across family types on child outcomes, intra-familial and contextual factors as well as risk and protective factors;

- investigate factors that explain differences in child outcomes within different family types;

- test whether factors that explain differences in child outcomes are different across family types; and

- clarify the relative importance of family structure, intra-familial processes and contextual factors on child outcomes.

11. Single-parent families are families in which all children are the biological children of a non-married, non-cohabitating man or woman.

12. Stepfamilies are families in which the study child is the biological child of one partner but biologically unrelated to the other partner.

13. Blended families are families containing at least one natural child of the couple and one stepchild of one parent.

14. Same-sex parent families are families in which children are parented by two adults in a gay or lesbian relationship who have either biological or social links with the study child.

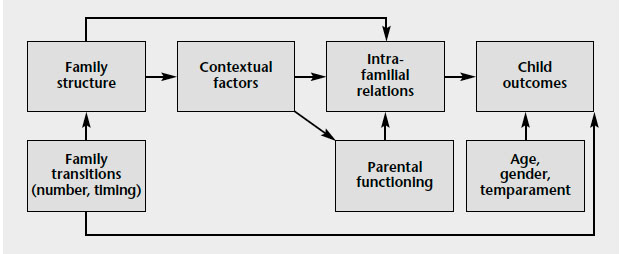

Family structure, intrafamilial processes and contextual factors: A theoretical causal structure