Understanding links between family experience, obligations and expectations in later life

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

June 1999

Download Research report

Overview

This paper examines meanings and expectations of family life and support for people aged 50 to 70, focusing on social relations between generations. Age cohorts and family life stage are not synchronous, so this age group represents a broad range of family and personal change, with conflicting roles and priorities in accommodating needs of both younger and older generation family members. Personal transitions and planning for old age are also pertinent.

Past research, plus new findings from the Institute’s Later Life Families case studies, underpin a discussion of: family policy and family support in old age; the interplay between family networks, dynamics, styles and personal behaviours; views of the role of government in supporting an ageing population; and expectations about family support in old age.

In this 1999 International Year of Older Persons it is appropriate to examine the experience and perceptions of people approaching old age. This working paper is the last in the Institute’s Later Life Families series, which focuses upon people aged from 50 to 70 years. It discusses family policy and family supports; the interplay between family networks, dynamics, styles and personal behaviours; views of the role of government in supporting an ageing population; and expectations about family support in old age.

The Institute’s Later Life Families study was designed to fill a gap in the literature regarding the experiences of people in their fifties and sixties. Much research into family life stage roles, responsibilities or relationships has focussed either on families with younger children or adolescents (Hagestad 1987), or on social gerontology, which essentially centres on the health issues associated with old age (Kendig et al 1983; Howe and Schofield 1996).

Instead, the present study explores the experience and life transitions of those in their fifties and sixties, the time of life which Laslett (1989) refers to as ‘the third age’ of personal fulfilment. However, because age cohorts and family life stage are not synchronous, the fifties and sixties also represent a broad range of personal changes – familial, physical, emotional, social and economic (see Wolcott 1998). People in this age group also tend to accommodate the needs of both younger and older generation family members, and in many cases are already the senior generation in their family (see Millward 1998a).

One of the important aspects of this ‘later life’ period is the anticipation of old age and planning for future contingencies (Wolcott 1998). While retirement may bring a decline in work and outside relationships, it may or may not lead to increased time spent with family members. Hagestad (1987) sees older, particularly retired, people as a rich resource both for society at large and for individual families, and Szinovacz and Ekerdt (1995) say there is a risk of over involvement with kin who need help. On the other hand, Troll, Miller and Atchley (1979) maintain that increased age in fact brings about a gradual withdrawal, not just from outside relationships, but from family connections too, as people let go of responsibilities or become less able to contribute to the family as they enter old age.

Family and public policy

An increased proportion of frail elderly in the population leads to increasing public debate about the provision of public services for future cohorts of elderly citizens. The support of an ageing population is increasingly perceived as a public problem and a challenge for future social policy planning (Officer 1996). One reason for this is that the proportion of citizens paying taxes to support welfare services for the older generation is purportedly dwindling, while the proportion of people in the older generation steadily increases. This results in increases in the ‘dependency ratio’ of dependent aged to taxpayers. For instance, there is a projected increase of people aged 65 years and over from 12 per cent of the in 1995 to 22 per cent in 2041 (ABS 1996). Also, with current lower fertility rates (de Vaus, Wise and Soriano 1997), an increasing number of elderly citizens in the future will have fewer or no adult children to call upon in older age.

However, in recent years, many Western societies have been moving away from a public welfare style of government, and economic considerations play a more dominant role in policy-makers’ decisions (Burbidge 1998). Because social and health services are seen as draining the economy, ‘the social objectives of care, equity and well-being of citizens become subordinate to cost-containment objectives’ (Hooyman 1992). Thus, care of the elderly is seen to be within the province of the community, largely within the family and supported by the unpaid labour of women (Hooyman 1992). Such policy pathways therefore appear inequitable for women.

Thus, we have a situation where more emphasis is placed on family responsibility, but we know there are groups of people approaching older age who will not have the family supports needed. Since public assumptions about the operation of family networks might be unrealistic, it is necessary to know what is happening in practice for people experiencing different family situations. In the words of Finch and Mason (1993: 10): ‘It is not enough simply to assume that the family as a social institution is ready, willing and able to shoulder the burden of supporting its members who cannot fully care for themselves, either practically or financially.’

What has characterised kin relationships in family theory is that they are commonly defined in terms of mutual obligation and responsibility (Klein and White 1996). Indeed, the Institute’s recent Australian Family Life Course Study (1996) asked 2685 adults some broad ‘values’ questions, which showed assent to the idea of obligations existing between adults and their parents. Almost all respondents agreed that parents and adult children should stay in touch on a regular basis (98 per cent) and most agreed that adult children should help parents financially if they need it (82 per cent). Most also agreed that parents should let adult children live with them (79 per cent) or help adult children financially where necessary (74 per cent) and there was majority support for allowing ageing parents to live with adult children (65 per cent or for adult children being responsible for taking care of ageing parents (69 per cent) (Millward 1998b).

Despite such in-principle assent for family obligation, Finch and Mason (1993) found little evidence in their large English study that people see specific duties or responsibilities attached to family relationships. They maintain that family obligations are fairly fluid (family commitments develop and change over time) and are negotiated (they do not conform to any hard or fast rules). In their study, help given to relatives and the opportunity to reciprocate could both depend upon circumstances beyond the control of the individual and sometimes upon individual choices or self-interest (Finch and Mason 1993). So opinion and behaviour can be out of step: family commitment might have an element of altruism but also entails exchange based on self-interest and long-term reward, which may reflect a conflict of interests between individuals (Klein and White 1996).

Family support

It is in the context of a changing social environment and increased economic uncertainty that the nature of family support needs to be more thoroughly examined in Australia. The interaction between the broader social and political climate and internal family dynamics may impact not only upon a person’s present experience of family involvement, but also upon their expectations and plans about sources of support in old age. Most of what we already know about family supports comes from large scale surveys such as the ABS Family Surveys and major Institute studies such as the Australian Living Standards Study of 1992–93 (ALSS).

The ALSS study interviewed 4,500 Australian family households, and found that the majority have some kin within reasonable proximity. Only around 5 per cent of households had no kin available at all (Millward 1996). Some people had a wealth of family and other informal resources while some (for instance, many sole-mother headed households) appeared to gain little help from extended family due to small or disrupted family networks (Millward 1996; also found in work by Thomson and Li 1992).

The large ALSS study also found that both proximity of relatives and contact with them were positively associated with expectations of financial, practical and emotional support from kin, with vertical generational links being stronger than horizontal links (Millward 1996). So interaction and exchange are more pronounced between adults and their parents than between adults and their siblings. Gender is also important in the mechanisms of kin networks. Women have more frequent contact with their wider family than men, and both men and women in the ALSS study gained more emotional and psychological support from mothers and sisters than from male relatives (Millward 1996).

Stage 1 of the more recent Later Life Families study found that family aid generally flows from older to younger generations, but that the middle generation – those in their fifties and sixties – provide most of the assistance in both directions (Millward 1998a). Later life respondents commonly helped elderly parents while still caring for dependent or semidependent children. Thus, many in this age group also fit the description of the ‘sandwich’ generation: they are sandwiched between simultaneous demands from both the younger and older generations (Stenberg-Nichols and Junk 1997).

However, the survey results showed that later life respondents were more likely to help their adult children than their elderly parents or parents-in-law, with 27 per cent still having adult children living with them, while only 3 per cent had an elderly parent living with them. Nevertheless, around 12 per cent were main carers for an elderly parent or parent-in-law (Millward 1998a). Such personal care was also clearly the province of the family, as less than half of those with ill or disabled parents used any formal support services in their caring role. This general lack of reliance upon formal services suggests that most later life carers were relying upon their own or their family’s resources to carry out their caring duties, as was also found by Howe and Schofield (1996) in their Carers Study.

For help flowing in the other direction, the Later Life survey found that later life parents with low incomes were more likely to receive practical help from adult children, while widows gained the most financial assistance. The losers were some later life fathers who had been divorced or separated. They had less frequent contact with adult children and were less likely than other parents to receive financial, emotional or practical support from their adult children (Millward 1997; also found in work by Furstenberg, Hoffman and Shrestha 1995). People with non-English-speaking backgrounds were less likely to have family members in Australia, and again, family care-giving and practical help was gendered, with women having more family involvement than men. The findings suggest that, while low income groups or older widows rely more heavily upon close relatives for practical and emotional support, they may still need public income support. Conversely, older divorced men and non-English-speaking migrants might have to turn towards the public sector, rather than family, for support (Millward 1997).

This paper seeks to go beyond the data quantifying levels of family association and exchange to see how personal background and family involvement influence family obligations. Therefore, the main questions asked by second stage interviews of the Later Life Families study relate to personal experience, needs and the exchange of family and non-family support, both now and in the future. The main questions were as follows.

- What are the mechanisms by which people maintain commitment to family networks, and are those with large family networks and nearby relatives necessarily more highly involved with family than others?

- Do those with adult children expect substantial help from them now or in the future,

and if so, what influences this expectation? - Do those without family support rely more upon friends and other community

resources than do those with family resources and, if so, are there any discernible

differences in outcomes? - Do those with family support less strongly endorse the need for public support

services for elderly citizens than those without family, and if so, is this because they

feel they can rely upon private sources?

It should be noted that case study findings are not generalisable to the wider population, due to the small number of interviews and the qualitative nature of the information. However, the strength of such information lies in gaining a fuller understanding of real family situations which will facilitate explanations of the survey findings and contribute to a firmer knowledge base about family dynamics at this stage of life.

Twenty-two Later Life Families respondents were selected as case study examples (see Appendix 2: Sampling) and their family linkages and dynamics were mapped using a modified version of the ‘genogram’. Genograms have been used by clinical psychologists as a visual representation of family links and relationships (across a minimum of three generations) for the purposes of exploring malfunctions in the family systems of patients undergoing therapy (Gewirtzman 1988). Here, they are a useful tool in providing a starting point from which to contrast widely varying family network types, so that beliefs and practices about family responsibility, exchange and caring can be better understood in the light of both personal experience and intergenerational family systems.

If the case study participants did not use family resources, they were asked whether or not they saw this as a problem either now or in the future. They were also asked how important their family connections are and what changes in intergenerational dynamics had affected family relations, exchange and expectations of obligation or reciprocity (see Appendix 1).

The other focus of the case studies was upon the private-public nexus of social support. Participants were asked what they felt influenced their preferences about sources of social support in general and what role they expected public supports to play in satisfying their own future needs. They were also asked what role they thought the government should play in providing income support, housing, medical and other services to the aged.

The genograms placed the participant at the centre of their family network, indicating their family situation as well as their personal relationships with the relatives listed.

Family networks varied greatly according to size, geographical spread and nature of ties. These three characteristics summarised the person’s family linkages, with relatives of both the participant and their spouse included. Some case study participants had small networks, such as a man with no living siblings, estranged from his ex-wife’s family, with only one child and an elderly mother. Other participants had huge networks on both partner’s sides. While some participants had most relatives living nearby, families were commonly ‘semi-dispersed’, with some relatives living either overseas, in other states or in country areas, as well as some living nearby (same city, suburb or district). Finally, participants could have many relatives to whom they felt emotionally very close, or conflictual or mainly detached relationships with relatives.

Discussion drawing upon all 22 cases is unwieldy when investigating the interplay between family network dynamics, behaviours and expectations about family support. Therefore, four cases selected to illustrate the different sorts of family situations mentioned above are presented in detail. The discussion which follows draws comparisons between the four cases, and uses information from some of the other 18 case studies to explain differences in family commitments, roles and dynamics.

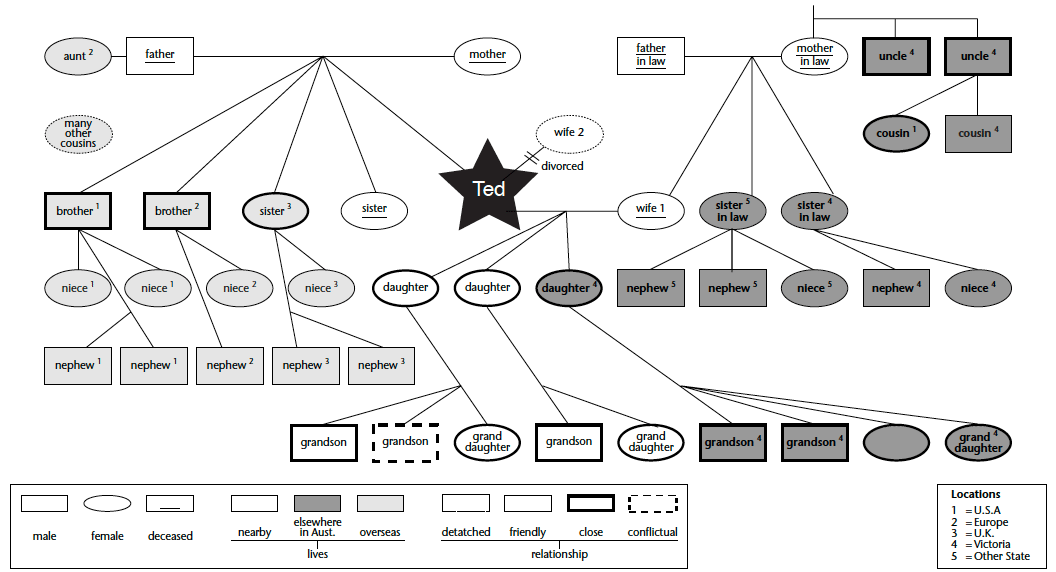

Case 1: Large family network, much involvement, many close connections

“Ted” was 70 years old. Although European by parentage, he had been born and raised in Indonesia, and had many relatives spread out all over the world. His first wife had died and he had recently been divorced from his second wife. Although officially retired, Ted had ‘many irons in the pot . . . I like to keep active’. He was a friendly, high energy man who lived alone, but was conducting several commercial enterprises from home as well as growing some of his own food. Ted’s family situation is illustrated by his genogram, presented here as Figure 1.

Figure 1. ”Ted” - Large network, much exchange and involvement

Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1999.

As Ted’s genogram (Figure 1) shows, Ted had three adult children, three siblings, nine grandchildren, 14 nieces and nephews and numerous cousins and in-laws. His is a widely dispersed family network: quite a number of close relatives living nearby, another set living in country areas or other states of Australia, and another set spread out internationally. He had close relationships or ‘connections’ with many of his relatives, and they flew around visiting each other when possible. He also had large phone bills due to international calls.

Thus Ted was highly involved with his family, which seemed quite cohesive. For example: ‘Last year my brother had his 50th Wedding Anniversary and his wife organised for all of the family to go there (South Africa). It was fabulous. She keeps the American and South African side of the family together and I do the European and Australian side generally . . . Yes, there’s a lot of interest in family. For instance, my brother-in-law in Perth has done the family tree for his family over there. My daughter number 3 is doing the family tree for this side.’

He also had a lot of relatives in Victoria: ‘I’m very close to my first wife’s two uncles. They’re actually the same age as her . . . and they both live in Victoria, so I see them quite a bit.’

His family also helped each other out as much as possible: ‘Money-wise we can give assistance even though we’re in different countries – we help where we can, especially for the children. Also, we give advice to each other. For instance, I keep them (my brothers and families) advised on health issues and alternative medicine. Probably I do most of the ringing – I’m more the contact person than anybody else. I welcome my family with open arms if they want to come here. I swapped a child with my sister (overseas) so each of us had a daughter living in the other country for a year. It was invaluable for their education in life. My brothers’ kids all want to come here now (ha ha). They ask me for family history. I visit them and they all know me.’

Ted’s immediate family also figured greatly in his life: ‘I’m proud to say that if my daughters need help or advice or assistance, they ring me. I’m happy about that. I love to be involved with them and the kids.’

Indeed, he was quite dedicated to his grandchildren: ‘We have to teach them that if there’s anything they want to achieve they can do it. They just have to work at it – just need the stickability. I took out study insurance for all my grandchildren to help them with Uni fees or training. Daughter number two is divorced and her kids especially need my help – I knew their father wouldn’t do it for them.’

He added: ‘I babysit any of them – here or at their place. I sometimes look after one if they’re sick during the day. Not very often at night though. I take them to sporting events and I’m the cheer squad. But they don’t prevent me from doing my own thing – I still go sailing or overseas when I want.’ So Ted’s commitment to the younger generations was somewhat tempered by exercising his own choices in life.

When asked who he would turn to for help, Ted said: ‘Whether people turn to their family for help or not depends very much upon their make up. For instance, Daughter number 3 (she became a widow at 31), is particularly independent. She says “I’ve got to cope, Dad, I know you want to help, but I’ve got to cope myself”. It makes it very difficult for me, I would like to help her and the kids more, but she doesn’t want to admit she needs anything.’ On the other hand: ‘If there’s anything wrong with me, my daughters are here like a flash. I don’t need to ask, they just pick it up and they’ll help me if they can. They’re terrific kids.’

He also felt confident about non-family help. Apart from some close friends, he said that he had ‘wonderful neighbours on both sides – if I needed them I just call.’

Concerning more formal resources, Ted thought that the government should provide the basic needs for old age, where required. He felt that people had the ‘right’ to a pension, because they had paid taxes to earn the right to future support. He pointed out that many of the present middle-aged generation have not planned or budgeted for total financial independence because they expected to be able to fall back on a pension if necessary. Therefore, changes in public policies cannot take place too quickly, but may need to take a whole generation (20–30 years) to change: ‘You can’t change it half way through – that’s not fair to people. It was not budgeted for, because Australia had a very young population. That’s all changed now – a lot are not married, and with the pill and everything, there’s a lot more older people now.’ He reasoned that if aged pensions become a problem because the younger (tax-paying) population is not increasing enough to cover future welfare bills, then those presently in their twenties and thirties should plan, as best they can, for financial independence in old age.

Nevertheless, when looking at his own adult children and grandchildren, Ted was rather concerned. He felt strongly that these young people will not enjoy the same employment security as did their parents and grandparents, so that planning ahead may be difficult for them. In fact, two of his daughters were in rather precarious situations financially, one recently widowed and one struggling with her own business.

His opinion of the current public hospital system was not very high: ‘I still have private insurance. I can’t really afford it, but I’m dead scared that if anything goes wrong, they’ll say “Look Charlie, we can’t do anything for you – you’re on the waiting list for 18 months’ time”. That’s no good, I want the treatment when I need it. I had some surgery a few years ago at a private hospital. I was insured, but it still cost me a fortune. They all charged above the agreed fees – I had to pay about half. But by the same token, I couldn’t wait for a public hospital bed – I might have carked it in the meantime!’ He felt that more money should be directed into the public system, since many people of his age are in worse financial situations than him.

When asked if the importance of family had changed as he grew older, Ted replied: ‘It’s definitely more important now. I’m still sorry about working such long hours when I was younger. I loved my job but the time was taken from family life and I’m sorry about it today. As the children grew older, I got to know them better – became friends now they’re adults. I feel that all of us, as we develop, we start to appreciate our parents more. I had a wonderful example from my own parents too, that you need to accept children as equals.’

‘When my first wife died it brought me closer to the girls. They were very, very supportive. They were in their early twenties and I couldn’t have had better friends. The eldest came to check up on me all the time. When I re-married, the girls were very keen for me to be happy . . . But my relationship with my youngest daughter changed after I divorced my second wife. She kept fairly close with my ex-wife, because she became the grandmother for that daughter’s children (they didn’t know my first wife who was their real grandma). So, she continued the relationship, which was difficult for me. Of course, it’s great for the kids to have a grandma. I have a good relationship with that daughter now. It’s okay.’

Finally, Ted was asked his thoughts about his own future. He said: ‘My kids are great, but if anything happens to me, so I can’t look after myself when I’m older, I’d want euthanasia. I don’t want to be a burden to my daughters – and I don’t want to live as a vegetable. What’s the point – you’re just taking up a bed or resources for no benefit to anyone. No thank you. I’d give my kids a letter telling them what to do. I’m very independent – I wouldn’t want to go into a nursing home either. They’d have to do what I say – it’s my life.’

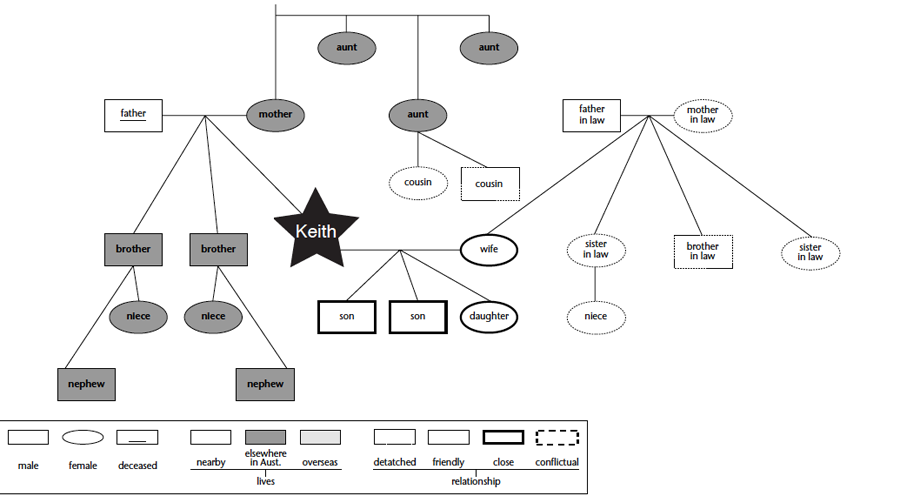

Case 2: Large network, many relatives nearby, few close connections

“Keith”, at 56, was a much younger man than Ted. He’d been born and raised in a Victorian country town, and had three adult children but no grandchildren. In contrast with Ted, Keith was a much quieter, private sort of person, who lived with his wife and only associated with her relatives, not with his own. He was still working full-time, but had been retrenched from a much better paid job and was bitter about this.

Figure 2. ”Keith” - Large network, little exchange or involvement

Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1999.

As Keith’s genogram (Figure 2) shows, one of Keith’s children still lived at home and the other two lived nearby. The older generation of his family still lived in country Victoria, but his brothers and their children were interstate. Although feeling fairly detached from his own wider family, his wife’s siblings were in Melbourne, so he saw smething of them.

However, Keith conceptually separated nuclear family from extended family relationships. His own wider family network was not an inter-connected system of prime importance, as was Ted’s, but was much more insular and much less relevant to him: ‘My family – we don’t look to each other at all really. We’re all sort of independent. Mum doesn’t need any help, but she could call on my brother who’s closest. I don’t have a role to play really, not directly.’

Of his brothers, he added: ‘We weren’t really close as kids. When we left home we learnt to live on our own – get an independent life and make your own way. Where we grew up (in a country town) there were no jobs – unless you wanted to work in a cafe. You had to move to get a job. I joined the bank, but to further my career I had to move on, move to the city. There was nothing to keep you there, no family farm to inherit or anything’. He added: ‘I don’t have much to do with nieces or nephews as such. Again it’s mostly the distance.’

Keith saw very little of his own mother either: ‘Mum’s still up home on her own. She’s perfectly capable of getting on by herself. Of course she’s got lots of people up there if she needs anything, because she knows everyone and they all know her.’ In Keith’s mind, the small community benefits of living in a country town were therefore evident for the older generation, but not for the middle or younger generations, due to lack of opportunity.

When talking about family roles, Keith therefore referred to his wife’s family: ‘My wife’s eldest sister lives nearest to their mother, so she helps there. But my wife would help where necessary. Their brother wouldn’t help much even though he lives with his mother. He wouldn’t know what to do.’ Keith felt that members of his wife’s family would turn to each other for help: ‘It would be within the family first, if anything happened to anyone and they needed help, before anyone outside.’ For himself, he said: ‘I’d turn to my wife first, but it would depend what the problem was I suppose. Maybe my daughter. It’s hard to say. I get some help from my brother-in-law, but I do most things on my own anyway.’

Despite some family back-up, his mother-in-law was also using formal services. ‘She has council help. Someone comes in and gets the tea for them (her and her son). She gets too tired cooking and he’s not much help, he wouldn’t worry about it, so they had to get someone in to make sure Mum eats it. They have to come in and bath her too, so it’s personal attention. Someone comes from the hospital service and someone comes from the council. She’s got one of these monitor alarms they wear round their necks too. The services take the load off the family – all the daughters work. If her son wasn’t living there, she’d already be in a home by now.’

Here, Keith quite strongly endorsed the use of community support services, which ‘should be subsidised by the government because mother is on a pension, like a lot of elderly people. The supports should be there for those who only need a certain amount of help.’ He also thought that the quality of service ‘should be monitored by the government’.

Nevertheless, Keith believed that people should pay their own way as much as possible regarding nursing homes: ‘I think that putting money toward a nursing home – to pay to get in – is just the thing that you do. They take a pretty high proportion of the pension too, of course, but you can’t expect the government to pay all that (that is, fees) while you hang on to the home.”

He had mixed feelings about broader public medical support, saying: ‘It depends what you’re looking for in medical attention really. You have a better chance of being looked after, when needed, if you’re in a private scheme – you’ve got a choice at least. But again, it’s the cost of the private scheme that’s the problem. I mean, many people can’t afford it. You’d expect the government to support people where necessary.’

For Keith, this included general income support. Both his mother and mother-in-law were aged pensioners, and he felt that: ‘People have paid their taxes and should expect something back from it. Where they’re wealthy, they shouldn’t expect it though.’ Nevertheless, he added that ‘you should put money towards your retirement, through superannuation. While you’re working you should be saving. But the truth is, people on low incomes can’t put enough towards their superannuation.’ In his own case, his job redundancy had negatively affected both his accrued savings and the value of his superannuation scheme. He felt this was through no fault of his own, so was bitter about his diminished circumstances.

When asked about the importance of family, Keith felt that his children were more important to him as they grew older, partly because he had had little to do with them when they were young. Now, as adults, he had a better relationship with them. However, Keith’s family in general had not become more important to him. He continued to have little to do with other family members, except the contacts with some in-laws which were maintained by his wife.

So, did he compensate for lack of contact with his brothers by socialising more with his friends? No. ‘I don’t know that I have a lot of friends. I have acquaintances but not really friends. It hasn’t really changed. I’ve never had friends where you’d go to each other’s places or go out together.’ So in this case, there was no evidence of the substitution of one support network for another.

Finally, when discussing expectations for the future, Keith felt he had a good role model in his own mother. She was still independent and living in her own home with ‘a good circle of friends’ and much community support and involvement. His mother-in-law was also still in her own home, although sharing with her son. Keith hoped that he and his wife could also stay in their home, maybe with the aid of domestic and nursing services. However, he also hoped that he could call on his children to help when needed.

He said: ‘You equate your position to the position your parents are in at the moment, and you hope that if you were in difficulty, then your children would start to look after you. Of course, that depends upon what kind of relationship you’ve had with them when they were younger. If things weren’t too good to start off with, then they might not be prepared to help you when you’re older. I hope mine will.’

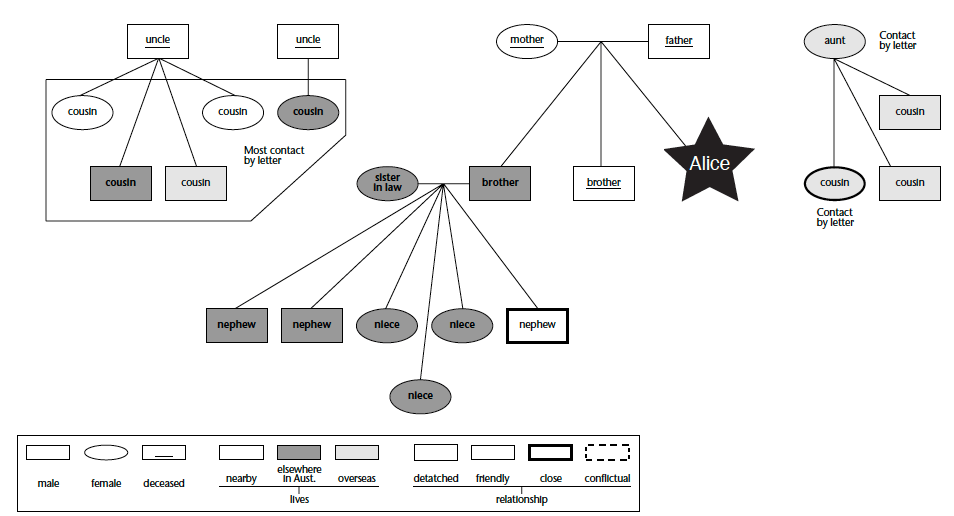

Case 3: Smaller network, few relatives nearby, no really close connections

“Alice” was a 67-year-old woman, also Australian born, who lived alone. Originally a trained nurse, she had never married, but had devoted her life to missionary work. Consequently, she had spent many years overseas. Now retired, she was living on an aged pension and was suffering from a number of health problems.

Figure 3. “Alice” Small network, little exchange or involvement

Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1999.

As Alice’s genogram (Figure 3) shows, one of her brothers was deceased and her older brother lived in the country, with his wife and five of his children. The only relative living near Alice was her youngest nephew, to whom she felt emotionally close. She had a number of cousins in Australia and overseas, but felt close to only one, to whom she mostly wrote letters. Thus, Alice was quite limited in terms of family relationships. ‘Of course, it was difficult to keep in touch because I was only home every three years on a furlough from my work overseas’.

Furthermore, Alice felt she was even more removed from her family network because of her older brother’s attitude. She had placed her own life and career ahead of what he saw as her duty to care for their elderly parents (now dead). She felt this pressure came because, as a woman who was an unmarried nurse, she was the obvious choice as carer, but she had refused to sacrifice her own life choices in order to care for her parents: ‘From the time mother died, I was home over an 18-month period. My father went into an advanced elderly extended care facility. In that time my brother saw more of him because he was nearer to the hostel. He really then needed 24 hour care . . . but I felt personally that I would have to be away working just to keep my own life and my own sanity. It just would not have worked out, as far as I was concerned.’

Regarding the younger generation of her family, Alice said: ‘They’re mostly scattered all over actually. They don’t see their parents that often, some of them only go home once a year (ha ha). Also, I think the young ones are very busy with their own families – some have children and, of course, they make more effort to see their own parents. If I want to visit them, I have to do the working out and make the arrangements – they don’t really make the effort to visit me. No, I’m rather on the outskirts – except for the youngest (nephew). He calls on me if there’s a need and tells me how things are going regularly. He’s been good back-up for quite a while – certainly for several years – and he goes to my church. He’s the only one who’s seen the retirement unit I’m moving to – and I think he’ll try to visit me there.’

Thus, apart from intermittent contact with this nephew, Alice realised that she was really ‘on her own’. She had to manage her own affairs and look after herself. Therefore, when asked who she would turn to for help, she replied: ‘Well, normally speaking I would have turned to my brother at this stage in my life – with my moving, you know, I’ve got all the packing and, of course, the financial side of it. I took some papers up there and tried to talk to him about it but he didn’t seem to be terribly interested. He didn’t see that I was looking for some back-up – a second opinion. He wasn’t forthcoming, so I didn’t bother him further . . . But he is my next of kin – you’d think he’d be interested . . . It was a bit of a shock to me not to have that back-up.’

She said that she would turn instead to a trusted friend or member of her church: ‘But I have to rely a lot on professional help – a solicitor or accountant, etc, since my closest friends were those I served overseas with. You’re forced to the conclusion that you’ve got to stand on your own two feet. So now’s the right time to make my arrangements for the future. If I’m more crippled with arthritis in another 5 or 6 years I wouldn’t be able to do it myself.’ Unlike Keith, Alice emphasised the importance of friends and church associates as substitutes for family. Of course, she did not have a spouse or in-laws either, as did Keith.

When asked about more formal support for ageing citizens, Alice suggested more joint ventures between governments and church or charitable organisations to establish low cost retirement units or villages with a community ambience: ‘My local church has just set up, jointly with the government, another set of units for socially deprived people to use. These joint ventures are a wonderful way to go.’

She also pointed out that many older women who had been out of the workforce or involved in volunteer work were unable to provide for their own future financially, particularly if single. She herself had to draw an aged pension, which she did not like, but: ‘Obviously, with my background there’s not much opportunity to put money away for the future. I was able to pay my mortgage for the flat through my paid work since returning home – but all that will be reinvested in the retirement unit, of course. Future planning and superannuation were the furthest things from my mind back then – I just had my job to do –with very little living allowance.’

Regarding medical services, Alice felt that private insurance ‘is way beyond an ordinary pensioner. I think that the government has to provide help. I’ve been really grateful this year with all my subsidised prescriptions – it’s helped so much. I’ve also been briefly in hospital too.’

She also had extensive knowledge of community support services: ‘Since I came home (14 years ago) I’ve been a hostel supervisor and a home care supervisor, so I’ve had a lot to do with helping the elderly in the community. But, while home and community care is good, I don’t like the government emphasis on keeping them in their own homes whatever the circumstances – or costs. That can be a bad thing for some of them. They’re pouring all their pension into trying to maintain an old, run-down house – their living standards deteriorate, maybe they can’t afford the heating in winter, etc. It’s wrong – many people would be better off in a hostel or home, with the company and security and care.’

When asked about changes in family salience, Alice said her family had always been important to her, but: ‘The thing we have to take into account is that most of these nephews and nieces are not following my faith and this leads to a certain lessening of closeness – except for the one nephew. There’s not the same urge or desire to maintain contact – from that point of view. They may feel I don’t approve of what they do – or their husbands – but never would I make any comment or try to make them change their ways.’ Nevertheless, religious differences obviously added to her sense of remoteness from family.

When asked about being childless, Alice said she had no regrets, although she said: ‘It’s not such a normal, fulfilled type of life, I suppose. But, as a teenager I knew I wanted to do the work of God and felt that I had been called. I really needed to be single to do that work, as a woman. I made that decision and so I lived by it.’

When considering her future, Alice had to be practical. Because of her lack of family support, she had made all the arrangements to move at a fairly young age into a retirement village, where she would have the company of people with similar religious views as well as the social interaction and sense of community which she found lacking in her life at present. Also, the facility had a hostel and nursing home, so she would have any nursing care needed when very elderly. Thus, despite being childless and disappointed in her family, Alice felt that old age was ‘not a problem’ because of concrete plans already made.

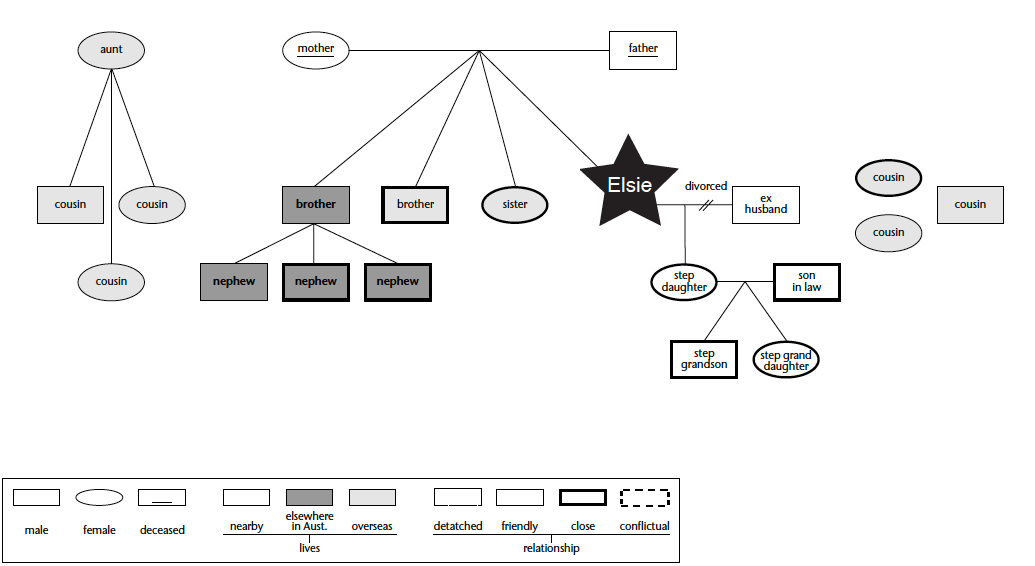

Case 4: Smaller network, few relatives nearby, some very close connections

“Elsie”, in her mid-fifties, also lived alone. She had left Europe 15 years previously and come to Australia for political freedom and a democratic way of life. ‘When I came here I hadn’t spoken English. I came here because I like the freedom. I had enough. I had a good job and home, but I left everything.’ She was heavily involved in a church and in professional therapy services which she offered from home.

Figure 4. “Elsie” Small network, much exchange and involvement

Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1999.

As Elsie’s genogram (Figure 4) shows, most of Elsie’s family were overseas or interstate. She had never had children and was separated from her second husband. However, this exhusband’s daughter lived nearby and Elsie saw a lot of her, her husband and their two young children. Elsie’s family, like Ted’s, is best described as a ‘long distance’ family, but is a much smaller network. She kept in touch constantly with relatives by telephone, letters and visits, as ‘we were very close when I lived in Europe’.

Her family was still extremely important to her, and their rather intense long-distance interaction was expensive, but worth it to Elsie. ‘I would love my family to be here, to be honest. I never feel lonely, but I love them – it would be so good to see them. I was 18 when my mother died, and I didn’t have a good relationship with my father. My sister was older and already left home, so I raised my two brothers.’

One of these brothers had also emigrated to Australia: ‘When he divorced he came here and for a while was living with me, but mostly we phone each other. He’s up in Queensland, so it doesn’t cost so much to phone him. But now, there are some problems with my brother’s sons because they live with their mother. If I could afford it, I would bring my nephews down from Queensland to stay with me. Before, they would all come to visit me and I went to them, but now it is hard because they are divorced.’

Of her wider family, she said: ‘No-one really takes on the role of organiser – it is too far for us to really organise anything. If we can afford it, then we get together, but otherwise we don’t.’

Her compensation was her nearby stepdaughter: ‘If she needs anything, I help with the children and I take them to the kindergarten or pick them up. Of course I feel I have a responsibility, even though she’s not my own daughter. They are my grandchildren and they’re very important. They’re so gorgeous – I see them nearly every day. They live very close – it’s easy to go there. They are aged two and three years. I teach them my language. Their parents speak it too, but they learn English at the same time (ha ha).’

However, Elsie emphasised choice in her care for these children. ‘I can do what I like – they always give me notice. I want to look after the children – don’t have to. It’s a pleasure.’

When asked who she herself would turn to for help, she said: ‘Of course, if my family were here, I’d go to them first. We were very close – with my cousins and aunts and brothers – but usually they came to get help from me! I had the resources. I could do anything to help them if they needed anything. They knew they could ask me. It’s different now, but if I need something, my stepdaughter can help me, or her husband, or friends.’

Also, Elsie was involved in a non-conventional church organisation which was a great source of comfort and support: ‘Everybody is very independent and everybody has their own things that they want to do, but when we get together, we can help each other. I can get counselling or therapy if I needed it. I haven’t done that so far, but it is there.’

In contrast, she was very wary of more formal support mechanisms. ‘I don’t like formal services – I don’t know why. I’d rather have informal help from friends or help from (church network).’ Nevertheless, she strongly endorsed the government providing basic income and medical support for the aged. ‘Most people have paid a lot of tax to the government so they deserve it. Even if you own your own house you still have to live on something.’

She added: ‘I don’t think many pensioners can afford private insurance. How can they afford it – it keeps going up and up? When I was in (a public) hospital the care was very good, but that was 14 years ago, so I’m not so sure about now. If someone is really very sick, then the waiting lists are not very good either.’ However, she was very negative about the quality of residential nursing homes: ‘I had a friend working in a nursing home, but she left. It was terrible how things changed. They didn’t have the things that they needed to look after so many sick people. They didn’t have the money for it – because the government took the support. The people who are running the nursing home have to live on something too. Everything costs more now – water, electricity.’

Instead, she said, it is much better to stay at home: ‘My grandfather was 89 years old when he died. He was still riding a bike till the age of 86. He never left his home till these last few years. He was so independent.’ But to stay at home, Elsie acknowledged that some formal services might be needed: ‘I think as you get older you can’t keep up all the work yourself – cooking and everything. Some can, but some can’t.’

While she was a strong and independent character, Elsie did not like leaving her family behind and placed a great deal of importance upon family and family ties, particularly the importance in her European culture, where ‘kids were taught to respect’ the older generations. ‘We lived with parents until you went to work and could afford to move. You gave money too. We all helped each other a lot, with the housework and everything.’

Regarding her own childlessness, Elsie explained that she had wanted children when young, ‘but I haven’t had time’. She said: ‘I raised my brothers and I was working. I was alone because it wasn’t long I was married to my first husband then I came over here. I just haven’t had time. For a long time I was a little bit sad about it, but not any more.’

Fortunately, her separation from her second husband had not damaged the relationship with her stepdaughter. ‘No, we were always close. The divorce is nothing to do with the children. The adults work it out together. You should keep children out of it.’

When thinking about the future, Elsie had no trepidation about old age. Although few relatives were nearby, she had her step-daughter and step-grandchildren, so she felt ‘very lucky’. However, she was more inclined to feel that her friends and religious associates, as well as some overseas relatives, would help her out if necessary in the years to come. She had no firm plans, except that she would not live in a hostel or nursing home. She was an optimistic woman and said: ‘I’ll be fine. Things always work out in the end.’

These four case studies illustrate variations in the degree of commitment to the wider family, views about the importance of a family network as a social support mechanism and the amount of interaction taking place.

Ted’s case supports the notion that people with large family networks and good relationships with family will be highly involved with family, while Keith’s relationship behaviours appear inconsistent with his family network pattern. His children and wife were important, but he did not have any role within his own wider family, nor did friendship networks substitute for family. This was partly due to distance, but Keith also expressed no normative behaviour in his own family regarding close association or commitment.

However, Ted provides some note of caution in assuming that those with good relations with adult children will expect help from them in the future. While he clearly had received support from his daughters, Ted never wanted to rely upon them too much, while Keith hoped that his adult children would help him in the future.

Alice also had a potentially large family network, but few relatives nearby and really only one with whom she had any involvement. Overall, her case shows that people can be essentially cut off from family networks and so have to be self reliant or turn to friends as substitutes. Elsie had the smallest family network and did not feel she would call on family as much as friends or other community networks. However, she did not feel cut off because her lack of involvement was purely due to distance and not sentiment. Alice’s case supports the notion that those lacking adult children and other family support will need to rely upon formal residential and support services in their own old age. Elsie also needed non-family supports, notwithstanding a good relationship with rejected any personal need for formal supports.

In the four examples presented, the preference was for help from family if available, then other informal supports. Nevertheless, all four felt the government should assist the elderly with public support services. Even though Ted had the largest and most interconnected family, he still felt that old age should not be a time to burden adult children because their financial circumstances may be quite tenuous.

Family connections and expectations obviously differed, but why was this so? If we consider the first two case studies, we see that Keith did not feel like Ted about family for several reasons: he had a wife to keep family contacts and to organise social events, while Ted did not; he had a rather non-committal family background where he had not been brought up to rely upon family or socialise with family past his teenage years; he had less intimate relationships with his adult children than did Ted, partly because of his wife’s role; he was not a grandparent yet; and he had a more reserved personality, being much less gregarious and sociable than Ted.

Considering the second two examples, Alice was not like Elsie because: she had no children or grandchildren to provide intimate and ongoing relationships; her past family relationships were such that relatives did not look to her for help or advice (even though both women had physically removed themselves from family networks); Alice had conflict with her only sibling, while Elsie got on quite well with hers; Alice had different values from Elsie, as she had put her own life ahead of her family, while Elsie had brought up her brothers; and, finally, Alice had a more reserved personality than did Elsie.

In both cases, personality styles and family importance may be somewhat linked to ethnic background, as the two Europeans, Ted and Elsie, seemed to have much clearer ideas of what family should be and what they wanted their role to be than did the two Australians, Keith and Alice. Also, Ted and Elsie could more easily be called ‘givers’, while the other two remained more aloof.

In addition to the effects of personality or family dynamics, it appears that a wider family network can either foster a tradition of close involvement (as in Ted’s case), or offer very little inter-connection (as with Keith). The examples studied offer some insight into the reasons behind these differences in family style: they can relate to circumstances, cultures, past relationships and individual personality.

Some general observations

Circumstances affecting involvement clearly include proximity of relatives, but this is best viewed as a catalyst for family relationships, and does not necessarily foster a sense of closeness, belonging or security in family network, nor does it guarantee exchange.

Indeed, in the context of cultural background, family cohesion can take on a very different meaning. For example, many of Ted’s relatives were far away, yet he spoke about the tremendous importance of family connections. Other case study participants, with relatives less dispersed, also found that frequent family contact was not necessary for feelings of solidarity. Rather, an understanding that they ‘are there’ for relatives to call on, and vice versa, was important.

Elsie had managed to maintain many close family relationships and considered herself the main family ‘kinkeeper’, despite the handicap of distance. She promoted interaction between kin members and thus helped form the ‘cohesive glue’ of the family. Indeed the generally feminine nature of the kinkeeping role has been shown to work in men’s favour until the link is severed. Keith’s story was a prime example of a man only having family linkages through his wife. Therefore, if his wife pre-deceased him or they separated, it is easy to imagine that his links with his in-laws and even those with his adult children, could become more tenuous. This certainly had happened in another case study, where a man had almost no family linkages at all since his wife died: ‘I left all that to my wife, and it was different when she was around. Now I’m just a provider of toys, that’s all. I don’t have much else to do with them.’

Both marital status and gender influenced a person’s sense of family belonging. Case study participants who felt isolated and lonely tended to be single men who either did not have any relatives, did not have good relationships with relatives or had ‘dropped out’ of the family network following divorce or widowhood. While this emphasises the role women can play as the medium via which some men are connected to the wider family, women like Alice could also feel isolated, while men like Ted (who was an example of the much less common male kinkeeper) could feel very closely bonded.

Furthermore, in certain instances, isolation from family was not viewed negatively by participants. There were men and women who had no involvement with their wider family and felt no commitment to family duty. Also, where a ‘togetherness ethic’ was not reported, this could either be ascribed to all the family or just to the individual interviewed. Keith felt his own family members would not make the effort to keep in touch. Other participants were relieved to have nothing to do with relatives, as this meant a quieter life. Therefore, both personal experience and psychological need appear to influence family attachment. Thus, being the ‘black sheep’ could result from personal preference or from conflicted relationships.

Elderly parents

The importance of past relationships for attachment was seen in the frequency of visiting elderly parents who lived in hostels or nursing homes. This was not necessarily linked to the state of health of the parent, but rather seemed to depend upon the nature of the past relationship between parent and child. Thus, certain people made a big effort to visit parents, and enjoyed doing so, while others felt estranged or antagonistic toward parents. Although people could feel obliged to look after quite objectionable old parents, for whom they felt very little affection, the element of choice in assisting parents was important if the experience was to be a positive or long term one (Millward 1999).

Caring for elderly parents was among several situations depicting the feminine character of family duty. For men, caring for parents was related to marital situation, because either couples or un-partnered women tended to do most of the caring. Nevertheless, there were instances of a consensus being reached among family members that the time had come for an elderly person to be placed in residential care, and in one case a woman and her sister had looked at around 60 different hostels and nursing homes to find care for both their father and mother: ‘It wasn’t easy, but we had to do it. The social worker at the hospital helped a lot.’

The comparative willingness of siblings to share the responsibility for elderly parents was sometimes evenly spread, but sometimes not. In cases where elderly parents are overseas, there was little choice. However, in some families, conflict was also caused by there being no consensus about a parent’s move into a nursing home. While some members of the family saw it as the practical course of action, others did not like the idea of residential accommodation at all (Millward 1999). Also, the situation of Keith’s mother-in-law raises the question of elderly parents who are still providing a home for an adult child. In such cases, the adult child may or may not be caring for their parent, but the elderly parent may feel they still have an obligation to the adult child. As such, the house cannot simply be considered an inheritance, and its sale to finance nursing home fees may be inappropriate.

Family tradition and expectations

Another element of family involvement was a person’s reaction to their own deprived or difficult childhood. For example, one woman who had left her relatives behind to emigrate to Australia felt she was better off without them. She had had an unhappy childhood and felt that her parents had neglected her. She now placed a heavy emphasis on her own parenting and grandparenting roles because she wanted to give her own children the sort of upbringing and support which she herself had missed.

Nevertheless, high family cohesion could also be a natural continuation of happy family experiences and feelings of belonging which participants were determined to perpetuate. Indeed, the case studies revealed perceptions that either a sense of attachment or detachment was perpetuated by successive generations, as relationship dynamics were echoed by family styles.

However, a sense of belonging did not necessarily lead to expectations of assistance, for not all of those who had good relationships with adult children expected support from them in the future. There were cases where good relationships existed and later life parents expected help (for example, ‘My daughter would help us . . . maybe have a flat attached to her house so we don’t encroach on their home too much’), but there were similar cases where case study participants did not expect help (for example, ‘I don’t expect my daughter to care for me. I’d consider a hostel. Then you don’t have to do everything yourself – you can get some help’).

Furthermore, although family styles could foster togetherness, support and sharing, there was a sense among certain participants that this sort of strong family involvement would not continue into the future because the present youngest generation (teenage or young adult children, nieces or nephews) do not have the commitment to family caring which their elders had. For example, one woman said: ‘It’s a different generation today. My kids won’t do it because everyone is too busy these days . . . The economy is more important than the community now, so what can you expect?’

On the other hand, there were people who felt strongly that a culture of family togetherness was being instilled into their children and that the family would continue in a closely linked fashion through the strong family commitment of the young. For example, one woman with a large, highly connected family saw her daughter as the next family kinkeeper: ‘My daughter will carry on the traditions – she’ll become the social organiser after me.’

The Later Life Families case studies show the huge diversity of family situations and commitments of people in their fifties and sixties. They also demonstrate the diversity of outcomes which can follow from seemingly similar starting points, in particular the existence of apparent mismatches between extent of family network and actual family involvement. The case studies also illustrate the ways in which different family styles or approaches lead to different levels of reliance upon family supports, as well different expectations about the likelihood of future dependency.

Family can be regarded as more important as people grow older, or less important, but these opinions do not appear to systematically reflect in any way the participant’s present level of family involvement. Nor was there any obvious link between extent of family network and individual involvement with elders. Again, it depended on individual circumstances.

More generally, the extent of family networks and level of integration within networks did not seem to differentiate later life peoples’ views on the right to receive public support in old age. These views were more individualistic in character and seemed to reflect a person’s life history in terms of economic independence, nature of employment and even cultural background. Although there was some divided opinion about the obligation of younger generations to support their elders, there was also some doubt that younger generations will have the same material means or sense of commitment to family as do the later life respondents themselves.

There was a strong consensus of opinion that the government should supply basic income support and medical care for the elderly. There was also enthusiastic support for continuing Home and Community Care services, so that people can retain their independence into old age without putting too much strain on other busy family members, particularly where difficult relationships exist despite some sense of obligation to help.

The most favoured outcome in old age was to stay independent as long as possible and this meant staying in your own home with a variety of family, informal and formal supports. Reliance upon the aged pension was not regarded as inconsistent with independence, as a pension was considered a right won by the individual during their lifetime. Rather, being dependent was viewed either as relying heavily upon family for accommodation or personal care, or as living in a hostel, or, more especially, a nursing home, where most autonomy was forfeited.

- ABS (1996), Projections of the Populations of Australia, States and Territories 1993–2041, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Catalogue No. 3222.0, Canberra.

- Burbidge A. (1998), ‘Changing patterns of social exchanges’, Family Matters, no. 50, Winter, pp. 10-17.

- de Vaus, D., Wise, S. & Soriano, G. (1997), ‘Fertility’, Chapter 5; ‘Marriage’, Chapter 2, in de Vaus, D. & Wolcott, I. (eds) Australian Family Profiles: Social and Demograhic Patterns, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Finch, J. & Mason, J. (1993), Negotiating Family Responsibilities, Tavistock/Routledge, London.

- Furstenberg, F.F., Hoffman, S.D. & Shrestha, L. (1995), ‘The effect of divorce on intergenerational transfers: new evidence’, Demography, vol. 32, no.3, August, pp. 319-333

- Hagestad, G. (1987), ‘Parent–child relations in later life: trends and gaps in past research’, in Lancaster, J.B. (ed.) Parenting Across the Life Span, Aldine de Gruyter Pubs, New York.

- Hooyman, N. (1992), ‘Social policy and gender inequities in caregiving’,in Dwyer J.W. & Coward, R.T. (eds) ‘Gender, families and elder care’, Sage Publications, California.

- Howe, A. & Schofield, H. (1996), ‘Will you need one, or will you be one, in the year 2004?: trends in carer roles and social policy in Australia’, in Towards a National Agenda for Carers: Workshop Papers, Department of Human Services and Health, AGPS, Canberra.

- Kendig, H. & Rowland, D.T. (1983), ‘Family support of the Australian aged: ANU ageing and the family project’, Gerontologist, vol. 23, no.6, pp. 643-649.

- Klein, D. M. & White, J. M. (1996), Family Theories: An Introduction, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, USA.

- Laslett, P. (1989), ‘Expectations of life: increasing the Ootions for the 21st century’, Chapter 10, Report by the House of Representatives Standing Committee for Long Term Strategies, April 1992, Commonwealth Government, Canberra.

- McDonald, P.F. (1997), ‘Older people and their families: issues for policy’, in Borowski, A., Encel, S. & Ozanne, E. (eds) Ageing and Social Policy in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

- Millward, C. (1996), ‘Australian extended family networks’, Masters Thesis (unpublished), Sociology Department, La Trobe University, Melbourne.

- Millward, C. (1997), ‘Divorce and family relations in later life’, Family Matters, no. 48, Summer/Spring, pp. 30-33.

- Millward, C. (1998a), Family Relations and Intergenerational Exchange in Later Life, Working Paper 15, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Millward, C. (1998b), ‘Family support and exchange’, Family Matters, no.50, Winter, pp. 19-23.

- Millward, C. (1999), ‘Caring for elderly parents’, Family Matters, no. 52, Autumn.

- Officer, R.R. (1996), Report to the Commonwealth Government, The National Commission of Audit, Australia (Chairman), AGPS, Canberra.

- Rosenthal, C. (1985), ‘Kinkeeping in the familial division of labour’, Journal of Marriage and the Family, November.

- Stenberg Nichols, L. & Junk, V.W. (1997), ‘The sandwich generation: dependency, proximity, and task assistance needs of parents’, Journal of Family and Economic Issues, vol. 18, no. 3, Fall.

- Szinovacz, M. & Ekerdt, D.J. (1995),’ Families and retirement’, in Blieszner, R. & Bedford, V.H. (eds) Handbook of Aging and the Family, Greenwood Press, Westport CT, USA.

- Thompson, E. & Li, Min (1992), Family Structure and Children’s Kin, NSFH Working Paper No. 49, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.

- Troll, L., Miller, S. & Atchley, R. (1979), Families in Later Life, Wodsworth Publishing, Belmont, California, USA.

- Winter, I. & Stone, W. (1998), Social Polarisation and Housing Careers,Working Paper No. 13, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Wolcott, I. & Glezer, H. (1995), Work and Family Life: Achieving Integration, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

- Wolcott, I. (1998), Families in Later Life: Dimensions of Retirement, Working Paper 14, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

LATER LIFE FAMILIES’ CASE STUDY INTERVIEWS – OCTOBER 1997

First construct genograms of family structure, proximity, contact, r/ships with participant.

a. Care and helping as part of family culture

- In general, are there areas of responsibility for different relatives in your family?

How does this work?

Why is this? (Are divisions along gender, generational, geographical or affectual/personality lines?) - For yourself, how do you see your role with the younger/older generations in your family?

Are there any barriers or impediments to giving or receiving assistance?

How about your relationship with in-laws? - If sick or disabled relatives, or frail elderly are being cared for by the family:

How did the arrangements come about? (generational dynamics?)

Have things changed over the course of time ?

In what ways and why?

How do you feel about these arrangements? Why?

Has the family used commercial or government services in this situation? If yes, how do you feel about these more formal services?

b. Hierarchy of social resources

- In general, do people in your family turn to family members first when they need assistance?

What about you? Why?

Do you prefer other informal or formal resources (give examples)? Why?

When you’re older, if you needed care, who do see caring for you?

Would you be happy using formal hostels or nursing homes? - Do you see the importance of family changing as you grow older?

How about involvement with friends and community, volunteering

Who do you spend Christmas with? - Do you see it chiefly as the role of the government to provide to older Australians:

income support (pensions)?special or low cost housing?

nursing and medical care? (Include question about nursing home fees). Other support services?

(HACS) Why do you feel this way?

c. Special conditions

For those who are grandparents

- How do you see your role as a grandparent & relationships with grandchildren? How much of your time and/or other resources do you invest in this role? What are the stresses and rewards?

- How does having grandchildren affect everyday life choices or planning for your future? Do you feel obligated to care for grandchildren? Do you resent this at all? Why?

For those who are divorced/separated

- Do you feel your relationship with any of your adult children has changed since your divorce/separation? With which ones? In what ways?

What about r/ships with your brothers/sisters, parents, friends?

Why do you feel this has happened?

For those who are widowed

- Do you feel your relationship with any of your adult children has changed since your widowhood? With which ones? In what ways?

What about r/ships with your brothers/sisters, parents, friends? Why?

For those with adult children who are divorced/separated

- Has your relationship changed with any of your adult children since their divorce or separation or widowhood? With which ones? In what ways?

How does this affect relationships with grandchildren?

For those who have (a) never married and/or (b) never been a parent

- Do you feel that not having had children poses any problems as you approach older age? Why do you feel this way?

Many people rely upon a spouse or adult child for assistance when they are elderly – especially if in ill-health. How do you see yourself as coping when elderly? Who do you feel you will turn to for assistance if needed?

The selection of cases required a sufficient range of family experiences, interactions and support (a) to explain the reasons for apparent consistency/ inconsistency between family resources and involvements, and (b) to explore individual reasons for future expectations and views on public support. From the 721 men and women surveyed in the first stage of the Australian Institute of Family Studies Later Life Families study, 22 case study participants were selected according to the following four criteria:

- They had agreed to be interviewed again.

- Some were divorced, widowed or were never married, to cover expected differences in the dynamics of family interactions, changes and possible re-negotiations of family relationships over time.

- Roughly equal numbers of men and women were selected to explore the stereotypes of gendered family roles and caregiving.

- They had contrasting family situations, with varying degrees of family network availability, interaction and involvement.

The fourth, and main, criterion meant a somewhat polarised selection of cases to maximise comparisons of those with or without extensive family connections, and of those with or without extensive family exchange. Four types of cases (A,B,C,D) were therefore selected as shown in the table

| Condition for selection of cases | Number completed |

|---|---|

| A. Have close same or younger generation family members living nearby, contact them often & help is exchanged. | (6) |

| B. Have close same or younger generation family members living nearby, but no interaction or exchange occurs. | (5) |

| C. Do not have close family members nearby, no contact or help exchanged. | (5) |

| D. Cases include those with elderly parents | (6) |

| Total number of interviews | 22 |

Note: Only a third had elderly parents, so parents did not figure in the selection process.

Respondents satisfying the sampling criteria were contacted by mail to request their participation in this second phase of the research and to explain the aims and purposes of the project. To contain costs and to enable the researcher to conduct all interviews personally, this sub-sample was drawn only from respondents living in the Melbourne metropolitan area.

The letters were followed a few days later by a telephone call to seek agreement to the interview and to set a convenient time and place. Most of the 22 interviews were conducted face-to-face, but four were conducted over the telephone. Written or verbal permission was obtained to audiotape some or all of the participants’ open-ended responses to questions. The interviews lasted between half an hour and two hours (Appendix 1 contains a list of subject areas and actual questions used in the interview).

Ilene Wolcott, Project Manager of the Institute’s Later Life Families study, is acknowledged for her advice and comments on drafts. Thanks are also due to Ian Winter of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, for helpful comments.

The main debt of gratitude is to the later life respondents, particularly the 22 case study participants, who gave of their time and discussed their intimate family experiences.

Millward, C. (1999). Understanding links between family experience, obligations and expectations in later life (Working Paper No. 19). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

0 642 39464 4