Neighbourhood influences on young children's emotional and behavioural problems

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

May 2010

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Place can facilitate opportunities or constrain and limit individuals, their families and communities. Although there is evidence to suggest that growing up in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods affects Australian children, little is known about what explains differences in the outcomes of children living in disadvantaged and advantaged neighbourhoods. In this article, Ben Edwards and Leah Bromfield examine the role that perception of neighbourhood safety and neighbourhood social capital play in explaining the differences in hyperactivity, peer problems and emotional symptoms for children living in socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods compared to advantaged ones.

Area-based initiatives to address the needs of children living in disadvantaged communities have been the focus of much policy interest in Australia and overseas. Several large-scale evaluations have suggested they can be effective in addressing the needs of children and their families (Raban et al., 2006; Edwards et al., 2009; Melhuish, Belsky, Leyland, Barnes, & National Evaluation of Sure Start Research Team, 2008). Research has shown that Australian children living in neighbourhoods with greater levels of socio-economic disadvantage are more likely to experience adverse outcomes than children living in more affluent areas (Edwards, 2005). However, little is known about what mechanisms explain differences in the outcomes of children living in disadvantaged and advantaged neighbourhoods. In this article, we will focus on how neighbourhood social processes (also referred to as neighbourhood social capital) affect young children's emotional and behavioural outcomes.

Internationally, there has been a trend towards a geographic concentration of poverty and affluence (Massey, 1996). For instance, the growth in income inequality between neighbourhoods since the 1970s in Australia mirrors the trends of other developed countries such as the US and Canada (Gregory & Hunter, 1995; Hunter & Gregory, 2001). More recently, Vinson (2007) showed that concentrated disadvantage was prevalent in all Australian states. He reported that when statistical local areas (SLAs) in each Australian state were ranked according to indicators of disadvantage, a small number of SLAs accounted for a large proportion of the instances of different types of disadvantage in each state. Vinson also showed that the strength of associations between indicators of disadvantage - such as unemployment rates and child maltreatment - were reduced in areas with higher levels of social cohesion (i.e., the strength of social bonds and connectedness of people living in an area), suggesting that neighbourhood social processes play a significant part in shaping the community's wellbeing.

The small body of research into neighbourhood influences on children's outcomes in early and middle childhood has shown that neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage has been consistently associated with a range of social, emotional and behavioural problems for children, even when controlling for family factors (e.g., Boyle & Lipman, 2002; Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Sealand, 1993; Chase-Lansdale & Gordon, 1996; Edwards, 2005; Greenberg, Lengua, Coie, & Pinderhughes, 1999; Kalff et al., 2001; Kohen, Brooks-Gunn, Leventhal & Hertzman, 2002; Romano, Tremblay, Boulerice, & Swisher, 2005; Xue, Leventhal, Brooks-Gunn, & Earls, 2005).

While the influence of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage on children is due to the characteristics of people and families living in disadvantaged communities (e.g., the education levels, employment, substance use of individual residents), the characteristics of the neighbourhood itself also influence children's development (over and above individual and family characteristics). One of the major limitations of previous research on neighbourhood influences has been that the mechanisms through which neighbourhood disadvantage may affect children's social and emotional outcomes have not been examined. In a broad sense, there are three possible mechanisms that have been proposed as explanations for the variation in children and youth outcomes by neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage. These are that:

- the quality, quantity and diversity of and access to recreational, social, educational, health, transport and employment services in the community directly affect child and youth outcomes as well as the outcomes of their parents;

- neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage has a detrimental impact on parental mental health, parental behaviour (e.g., parenting style, supervision and monitoring, routines and structure), and the quality of the home environment, which in turn affects child and youth outcomes; and

- neighbourhood social processes (i.e., the social connections between parents in the neighbourhood that encourage trust, support and a shared understanding and norms of behaviour) are undermined for those living in more disadvantaged areas, which then affects child and youth outcomes (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000).

A recent US study that investigated possible mechanisms through which neighbourhoods influence children's outcomes showed that the effects of neighbourhood socio-economic status on children's internalising behaviour were explained by residents' involvement in local organisations and "collective efficacy" (a construct that combines shared expectations and mutual engagement by residents in civic control) (Xue et al., 2005). In this study, higher levels of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage were associated with higher levels of internalising problems for children, but once residents' involvement in local organisations and collective efficacy were taken into account, the relationship between neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage and internalising problems was no longer significant. Similar patterns have also been observed for Canadian 4-5 year olds; for example, Kohen, Leventhal, Dahinten and McIntosh (2008) recently reported that neighbourhood social cohesion plays a role in reducing the impact of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage on children's behaviour problems.

Existing research supports the argument that residents' perceptions of the neighbourhood are important. For example, in Australia, Edwards and Bromfield (2009) showed that parents' perceptions of neighbourhood safety and sense of neighbourhood belonging explained differences in Australian children's levels of conduct problems due to neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage (but not prosocial behaviour; see also Shumow, Vandell, & Posner, 1998).

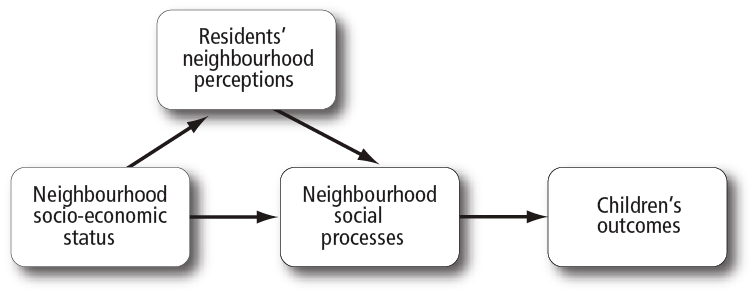

Although these studies advanced our understanding of the role played by neighbourhood social processes, further research is required to determine whether these processes mediate the effect of neighbourhood socio-economic status on other types of social and emotional outcomes for children. In a promising theoretical model for understanding the way in which neighbourhood social processes affect children's outcomes, Roosa, Jones, Tein, and Cree (2003) proposed that:

- neighbourhood socio-economic status influences both residents' perceptions of their neighbourhood and neighbourhood social processes;

- residents' perceptions of their neighbourhood also affect neighbourhood social processes; and, in turn,

- neighbourhood social processes affect children's outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Model of neighbourhood influences on children's outcomes (based on Roosa et al., 2003)

In the present study, we investigate the effects of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage, residents' perceptions of the neighbourhood and neighbourhood social processes on 4-5 year old children's hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems using data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC).

In this article, we answer a series of interrelated questions:

- We test whether there are differences between children's level of hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems by area of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage.

- We identify what residents' neighbourhood perceptions and neighbourhood social processes influence child outcomes.

- To test Roosa et al.'s model, we investigate whether neighbourhood social processes explain the influence of residents' neighbourhood perceptions.

- We examine whether residents' neighbourhood perceptions and neighbourhood social processes explain differences in the behavioural and emotional outcomes of children living in disadvantaged compared to advantaged neighbourhoods.

Method

Postcodes as neighbourhoods

In this study, we used 330 Australian postcodes, which each have between 12,000 and 15,000 residents. US studies of neighbourhood influences on children have commonly used census tracts to define neighbourhoods, which are smaller than Australian postcodes (with 2,500 to 8,000 residents) (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000).1 Administratively defined units such as Australian postcodes and US census tracts enable aggregated census information about neighbourhood characteristics to be included in the study of neighbourhood effects.

Participants

LSAC was designed to provide a nationally representative sample of Australian children's experiences as they grow and develop. For the current study, we used Wave 1 data for the 4-5 year old cohort (children born between March 1999 and February 2000; n = 4,983; collected in 2004). The study sample was randomly selected from the Health Insurance Commission's Medicare database. A further description of the design and sampling of LSAC can be found in Gray and Smart (2008). Survey weights were used to ensure that the sample was representative on a range of demographic characteristics (Soloff, Lawrence, Misson, Johnstone, & Slater, 2006).

Text box 1: Measures

Child functioning: Hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems

Three of the five scales from the parent-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) were used to assess child functioning: Hyperactivity, Emotional Symptoms and Peer Problems. Hyperactivity scale assesses the child's restlessness, concentration span and impulsiveness. The Emotional Symptoms scale measures the child's tendency to display negative emotional states such as sadness, fear or worry. The Peer Problems scale assesses problems such as the child not having friends, not being liked, being picked on, playing alone or preferring adult company. Neighbourhood influences on Conduct Problems and Prosocial Behaviour, the other two scales of the SDQ, were the focus of a previous study (Edwards & Bromfield, 2009).

Parental perceptions of the neighbourhood

Four measures of residents' neighbourhood perceptions were employed from parent reports: neighbourhood facilities, neighbourhood belonging, neighbourhood safety and neighbourhood cleanliness.

Neighbourhood facilities comprised six items that asked parents to rate their neighbourhood's parks, playgrounds and play spaces; street lighting; footpaths and roads; access to close, affordable, regular public transport; access to basic shopping facilities; and access to basic services like banks and medical clinics. Neighbourhood belonging consisted of four items that assessed parents' trust of neighbours, a sense of identity with the neighbourhood, how well-informed they were about local affairs, and knowledge about where to find information about local services. Neighbourhood safety and neighbourhood cleanliness were each assessed by one item respectively: "This is a safe neighbourhood" and "This is a clean neighbourhood". Additional analysis confirmed that neighbourhood facilities and belonging were independent concepts (see Edwards, 2006, for details).

Neighbourhood measures derived from administrative data

Consistent with previous work on neighbourhood influences on children (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000), we included neighbourhood-level (postcode) measures of neighbourhood socio-economic status, residential instability, ethnic homogeneity and area remoteness, extracted from administrative data (the 2001 Census of Population and Housing).

Neighbourhood socio-economic status was measured by the Index of Advantage/Disadvantage of the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). Lower scores indicate more disadvantage and less advantage and higher scores indicate the reverse. The SEIFA is a composite of 31 variables, such as income, unemployment, occupation and education. The validity of the Index of Advantage/Disadvantage has been established by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (Trewin, 2004).

Neighbourhood residential instability was measured using ABS Census data at the postcode level that recorded the percentage of residents in the neighbourhood who had moved in the last 5 years.

Neighbourhood ethnic homogeneity was assessed by the percentage of residents in the postcode who had been born in Australia.

Remoteness of the neighbourhood was measured by the Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA; ABS, 2006). The ARIA measures remoteness based on road distances to 201 centres where services are located. The index does not include socio-economic and population size indicators and comprises five categories that reflect the remoteness from a range of goods and services and opportunities for social participation (highly accessible, accessible, moderately accessible, remote and very remote). As there were very few postcodes in this study sample that were remote (n = 11 postcodes, 3.2%) or very remote (n = 5 postcodes, 1.5%), these two ARIA categories were grouped together for this study.

Interviewer observation of neighbourhood physical disorder

The current study includes an observation of physical disorder derived from interviewers' ratings of the general condition of buildings nearby the family residence. Specifically, interviewers were asked to rate buildings within 100 metres of the study child's house. Interviewers reported whether the nearby buildings were badly deteriorated, in poor condition and in need of repair, in fair condition, well-kept or if there were no other dwellings nearby. As only a small minority of buildings were rated as badly deteriorated (n = 51, 1.0%) and in poor condition (n = 100, 2.0%), these categories were combined with those in fair condition (n = 1,064, 21.4%). Thus, the physical disorder measure comprised three categories: bad to fair, well-kept and no other dwellings nearby.

Family demographic characteristics

Several variables were also included to control for factors that may predispose families to live in particular neighbourhoods: parents' combined weekly income (here called family income), mother's level of education, in a single-parent household, in a household where no one worked, and in a household where one or both parents were born overseas. We also accounted for child demographic factors that are known to be associated with children's outcomes (child's gender and age, whether the child was of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin). The descriptive statistics for child outcomes, family and child characteristics, and neighbourhood variables are provided in Appendix A (Table A1).

Text box 2: Statistical analyses

We used multilevel models to analyse the data (see Appendix B for a detailed description). Multilevel models accounted for the fact that the LSAC study sampled multiple children from the same postcodes and, as a consequence, children who lived in the same postcode were likely to have more similar outcomes than children residing in different postcodes. We ran three related multilevel models for each of the three outcomes.

In the first model, neighbourhood socio-economic status, neighbourhood residential instability, neighbourhood ethnic heterogeneity, remoteness and physical disorder were included, along with the child and family demographic variables to control for selection into the neighbourhood. This enabled us to derive an estimate of the difference between children residing in the five levels of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage, which controlled for child and family demographic variables, neighbourhood residential instability, neighbourhood ethnic heterogeneity, remoteness and physical disorder.

In the second model, the three measures derived from parent perceptions of their neighbourhood were added: neighbourhood facilities, neighbourhood safety and cleanliness. The second model allowed us to: (a) see whether differences between children residing in the five levels of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage were reduced; and (b) to assess whether any of these variables had a significant association with the outcome variable.

The final model included our measure of neighbourhood social processes: residents' perceptions of neighbourhood belonging. The aim of the third model was to see whether neighbourhood belonging explained additional differences in the outcome for children residing in the five levels of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage over and above the differences accounted for by residents' neighbourhood perceptions. The second aim was to assess whether there was a significant association between neighbourhood belonging and the outcome variable. Detailed results for the three models for each of the child outcomes (peer problems, emotional symptoms and hyperactivity) can be found in Appendix A (Tables A2 to A4).

Results

Neighbourhood socio-economic status was measured by the SEIFA Index of Advantage/Disadvantage (Trewin, 2004). We separated neighbourhood socio-economic status into five levels (quintiles), with the first quintile being the most disadvantaged, and the fifth quintile the most advantaged (see Text Box 1 for more details). All of the results presented are derived from statistical models that account for child and family demographic variables (see Text Box 1 and Appendix B for more details).

Are there differences in children's outcomes due to the level of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage in the area in which they live?

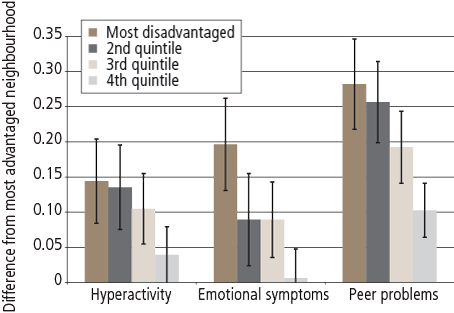

Figure 2 shows the differences in children's behavioural and emotional problems between children living in different areas of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage after differences in weekly family income, child age and gender, child Indigenous status, single-parent family status, parental employment status and mother's education are taken into account. The "I" bars on the columns represent 95% confidence intervals; "I" bars that do not overlap are significantly different at the 95% level of confidence. The columns represent the difference in children's outcomes from children living in the most advantaged neighbourhood socio-economic quintile.

Figure 2: Differences between children's level of hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems, by neighbourhood disadvantage2

Source: LSAC Wave 1

There are several points to note. First, compared to children living in the most advantaged neighbourhood socio-economic quintiles, children living in the most disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles had significantly worse hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems. Second, these differences were largest for peer problems. Compared to children living in the most advantaged neighbourhoods, the largest differences for children living in the two most disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles was 0.28 and 0.26 of a standard deviation respectively. Compared to other variables in the same statistical model, this is quite a large difference. For instance, the difference between children where both parents were not employed compared to where at least one was employed in the same statistical model is 0.13 of a standard deviation. Third, for emotional symptoms, differences by neighbourhood socio-economic status were much greater for children living in the most disadvantaged compared to the most advantaged neighbourhood quintiles (at 0.20 of a standard deviation) than for children residing in the second, third and fourth neighbourhood quintiles. Fourth, the differences by neighbourhood socio-economic status for children's level of hyperactivity were the smallest of all the three outcomes. However, the differences between the three most disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles and the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile were still statistically significant.

To summarise, while there is some variation in the findings for hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems, there are statistically significant and meaningful differences between children living in disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles compared to those living in the most advantaged neighbourhood quintiles. This is consistent with the majority of studies that have examined the influence of neighbourhood socio-economic status on children's behaviour problems and emotional symptoms (e.g., Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Living in an affluent neighbourhood seems to be particularly beneficial, with children living in the most advantaged neighbourhoods being significantly better off than even those living in the second quintile. These findings mirror those for a study of Canadian children's behaviour problems at approximately the same age (Kohen et al., 2002).

What resident neighbourhood perceptions and neighbourhood social processes influence child outcomes?

The analyses indicate that of the resident neighbourhood perception variables examined, only neighbourhood safety had a statistically significant association with children's levels of hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems. A one-unit increase in neighbourhood safety was associated with a 0.07 of a standard deviation reduction in hyperactivity, 0.08 standard deviation reduction in emotional symptoms and 0.13 standard deviation reduction in peer problems. However, neighbourhood belonging had an even stronger association with children's outcomes. A one-unit increase in neighbourhood belonging was associated with even lower levels of hyperactivity (-0.15 of a standard deviation), emotional symptoms (-0.14) and peer problems (-0.19) than a one-unit increase in neighbourhood safety.

Do neighbourhood social processes explain the influence of residents' neighbourhood perceptions?

Earlier, we described a theoretical model by Roosa et al. (2003) proposing that residents' perceptions of their neighbourhood are related to neighbourhood social processes (Figure 1). The statistical modelling we conducted supports this theoretical model, with neighbourhood belonging explaining the influence of neighbourhood safety on hyperactivity in particular, but also emotional symptoms and peer problems (see Table 1 notes for details of these statistical tests). This suggests that neighbourhood safety is an important precondition for neighbourhood belonging but that it does not directly influence children's hyperactivity and emotional symptoms (there is still a direct influence of neighbourhood safety on children's peer problems). When parents live in a safe neighbourhood they are also more likely to feel a sense of belonging to their area, trust their neighbours, keep informed about local affairs and know where to find information about local services and it is these latter factors that directly influence children's development.

| Child outcomes | Neighbourhood variables | Effect size change in child's outcome with a one-unit change in neighbourhood variable | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety only | Belonging added | ||

| Hyperactivity | Neighbourhood safety | -0.07* | -0.04 |

| Neighbourhood belonging | -0.15*** | ||

| Emotional symptoms | Neighbourhood safety | -0.08* | -0.07 |

| Neighbourhood belonging | -0.14*** | ||

| Peer problems | Neighbourhood safety | -0.13*** | -0.10* |

| Neighbourhood belonging | -0.19*** | ||

Notes: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Sobel tests suggested that neighbourhood belonging mediated the relationship between neighbourhood safety and children's hyperactivity (Sobel test statistic = 4.44, p < .001), emotional symptoms (Sobel test statistic = 4.30, p < .001) and peer problems (Sobel test statistic = 5.93, p < .001).

Source: LSAC Wave 1

Do resident neighbourhood perceptions and neighbourhood social processes explain the differences in the outcomes of children living in disadvantaged compared to advantaged neighbourhoods?

Figure 3 presents the differences in children's levels of hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems for children living in the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile and those living in the other four more disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles for the two statistical models. The first set of columns (SES only) is the same as in Figure 2 and shows differences in children's behavioural and emotional outcomes in the four most disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles compared to the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile, after accounting for family and child demographic variables. The second set of columns (Safety and belonging) also shows differences in children's outcomes between the four most disadvantaged compared to the most advantaged quintile but, crucially, this is after including the resident neighbourhood perceptions and neighbourhood social processes variables. By comparing these two sets of columns we can estimate how much of the gap in children's outcomes due to neighbourhood socio-economic status can be closed by neighbourhood safety and neighbourhood belonging.

Figure 3: Differences between children's level of hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems, by neighbourhood disadvantage, before and after including neighbourhood safety and belonging

Source: LSAC Wave 1

There are several points to note from Figure 3. First, the overall size of the differences between the four more disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles and the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile is reduced when neighbourhood safety and belonging are included in the statistical model. This suggests that neighbourhood safety and neighbourhood belonging explain some of the differences in children's behavioural and emotional problems. This is an important finding, as it suggests that there is a role for community development in fostering the social capital in poor neighbourhoods as one way of promoting children's behavioural and emotional development.

Although neighbourhood safety and belonging explain some of the differences between children living in the five neighbourhood quintiles of socio-economic disadvantage, they do not close the "gap" in many instances. For emotional symptoms, the differences between children living in the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile and those living in the second and third most disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles were no longer statistically significant after taking into account neighbourhood safety and belonging, but there were still statistically significant differences between children living in the most advantaged and disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles (albeit reduced by 21%).

There was a similar pattern for hyperactivity, with differences between children living in the third most disadvantaged neighbourhood quintile and the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile being no longer statistically significant after accounting for neighbourhood safety and belonging. There were still statistically significant differences between children living in the two most disadvantaged neighbourhood quintiles and the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile.

For peer problems, the size of the differences between the most advantaged and four more disadvantaged quintiles was reduced by 0.06 of a standard deviation for children living in each of the most disadvantaged three quintiles. However, there were still statistically significant differences between children living in the most advantaged neighbourhood quintile and the four more disadvantaged quintiles.

These results suggest that strategies that promote neighbourhood social capital can play a role in addressing the needs of children growing up in disadvantaged neighbourhoods and reducing the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

However, in isolation, this will not be able to close the gap between children living in the most advantaged and disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

Were the quality of neighbourhood facilities important?

Although parental perceptions of neighbourhood safety were associated with the majority of children's behavioural and emotional outcomes, parents' perceptions of the quality of neighbourhood facilities did not appear to be important (see Tables A2 to A4 in Appendix A). These findings suggest that residents' perceptions of the quality of various neighbourhood facilities are not as crucial as other aspects of the neighbourhood, such as perceived safety and sense of neighbourhood belonging.

It is possible that a measure of the availability rather than the quality of neighbourhood facilities/services, or questions that focused more specifically on the quality of early childhood services, such as child care, preschool and maternal child health, would have been more sensitive than the current measure. The findings from the evaluation of an area-based program that enhances the coordination, relevance and - crucially - the number of early childhood services delivered by non-government organisations in disadvantaged communities has had some positive early impacts, suggesting that neighbourhood facilities are important (Edwards et al., 2009; Muir et al., 2010).

Strengths and limitations of the current study

Only a few previous studies (Edwards & Bromfield, 2009; Kohen et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2005) have explored the mechanisms by which neighbourhood socio-economic status influences children's emotional outcomes, and this is only the second Australian study to do so. All of these studies suggest that neighbourhood social processes play an important role in the transmission of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage to children.

The present study has some limitations. Neighbourhood effects may be due to decisions parents make about the neighbourhoods in which they choose to live (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). However, all neighbourhood studies based on non-experimental data have this limitation and we attempted to reduce the possibility of selection bias by controlling for relevant child and family demographic characteristics.

Conclusion

Like other studies in this area, we find that the degree of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage is related to children's levels of hyperactivity, emotional symptoms and peer problems, and that neighbourhood safety and belonging also influence children's behavioural and emotional problems. Neighbourhood social processes like neighbourhood belonging do play a role in explaining the influence of neighbourhood disadvantage on children's behavioural and emotional problems.

These findings are consistent with the model of neighbourhood influences proposed by Roosa et al. (2003), which proposes that perceptions of the neighbourhood and neighbourhood belonging mediate the effect of neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage on children's behavioural and emotional outcomes.

Although important, our results suggest that enhancing neighbourhood social capital reduces, but does not close the gap between children living in advantaged and disadvantaged neighbourhoods. There were still some significant differences between children growing up in the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods compared to the most advantaged neighbourhoods.

While building social capital is clearly important, addressing the service delivery system, enhancing parenting skills and providing employment in these areas are also important elements of a comprehensive strategy in addressing area-based disadvantage.

Endnotes

1 Although Australian postcode areas are larger than the census tracts commonly used by researchers in the US, postcodes have been used in previous Australian neighbourhood effects research (e.g., Andrews, Green & Mangan, 2004) and some US studies have combined census tracts, making the "neighbourhood" comparable to that encapsulated by Australian postcodes (see Xue et al., 2005). However, we would expect our results to be conservative and slightly underestimate neighbourhood effects due to the greater heterogeneity within larger units of analysis. Nevertheless, theories of neighbourhood effects would still be relevant.

2 Multiparameter tests suggested that neighbourhood socio-economic status influenced children's levels of hyperactivity (χ2(4) = 11.35, p < .05), emotional symptoms (χ2(4) = 13.61, p < .01) and peer problems (χ24) = 28.80, p < .001).

References

- Andrews, D., Green, C., & Mangan, J. (2004). Spatial inequality in the Australian youth labour market: The role of neighbourhood composition. Regional Studies, 38, 15-25.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) Concordances, 01 Jul 2006 (ABS Cat. No. 1216.0.15.002) Canberra: ABS.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

- Boyle, M. H., & Lipman, E. L. (2002). Do places matter? Socio-economic disadvantage and behavioural problems of children in Canada. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 378-389.

- Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G. J., Klebanov, P. K., & Sealand, N. (1993). Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? American Journal of Sociology, 99(2), 353-395.

- Chase-Lansdale, P. L., & Gordon, R. A. (1996). Economic hardship and the development of five- and six-year-olds: Neighborhood and regional perspectives. Child Development, 67, 3,338-3,367.

- Edwards, B. (2005). Does it take a village? An investigation of neighbourhood effects on Australian children's development. Family Matters, 72, 36-43.

- Edwards, B. (2006). Views of the village: Parent's perceptions of the neighbourhoods they live in. Family Matters, 74, 26-33.

- Edwards, B., & Bromfield, L. M. (2009). Neighbourhood influences on young children's conduct problems and prosocial behaviour: Evidence from an Australian national sample. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 317-324.

- Edwards, B., Wise, S., Gray, M., Hayes, A., Katz, I., Misson, S., Patulny, R. &

- Muir, K. (2009). Stronger Families in Australia Study: The impact of Communities for Children (Occasional Paper No. 25). Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology, Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581-586.

- Gray, M., & Smart, D. (2008). Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children is now walking and talking. Family Matters, 79, 5-13.

- Greenberg, M. T., Lengua, L. J., Coie, J. D., & Pinderhughes, E. E. (1999). Predicting outcomes at school entry using a multiple risk model: Four American communities. Developmental Psychology, 35(2), 403-417.

- Gregory, R. G., & Hunter, B. (1995). The macro economy and the growth of ghettos and urban poverty in Australia. Canberra: Economics Program, Research School of Social Science, Australian National University.

- Hunter, B., & Gregory, R. G. (2001). The growth of income and employment on inequality in Australian cities. In G. Wong & G. Picot (Eds.), Working time in comparative perspective: Patterns, trends and the policy implications of earnings inequality and unemployment (pp. 171-199). Kalamazoo, MI: W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

- Kalff, A. C., Kroes, J. S. H., Vles, J. S. H., Hendriksen, F. J. M., Steyaert, J., van Zeban, T. M. C. B., et al. (2001). Neighborhood level and individual level SES effects on child problem behaviour: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55, 246-250.

- Kohen, D., Brooks-Gunn, J., Leventhal, T., & Hertzman, C. (2002). Neighborhood income and physical and social disorder in Canada: Associations with young children's competencies. Child Development, 73, 1,844-1,860.

- Kohen, D., Leventhal, T., Dahinten, V. S., & McIntosh, C. N. (2008). Neighborhood disadvantage: Pathways of effects for young children. Child Development, 79, 156-169.

- Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309-337.

- Massey, D. S. (1996). The age of extremes: Concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography, 33(4), 395-412.

- Melhuish, E., Belsky, J., Leyland, A. H., Barnes, J., & National Evaluation of Sure Start Research Team. (2008). Effects of fully established Sure Start Local Programmes on 3-year old children and their families in England: A quasi-experimental observational study. The Lancet, 372, 1,641-1,647.

- Muir, K., Katz, I., Edwards, B., Gray, M., Wise, S., Hayes, A., & the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy evaluation team. (2010). The national evaluation of the Communities for Children Initiative. Family Matters, 84, 35-42.

- Pfeffermann, D., Skinner, C. J., Holmes, D., Goldstein, H., & Rasbash, J. (1997). Weighting for unequal selection probabilities in multilevel models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, B, 60, 23-40.

- Raban, B., Nolan, A., Semple. C., Dunt, D., Kelaher, M., & Feldman, P. (2006). Statewide evaluation of Best Start: Final report. Melbourne: University of Melbourne

- Rasbash, J., Steele, F., Browne, W., & Prosser, B. (2004). A user's guide to MLwiN version 2.0. London: Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Romano, E., Tremblay, R. E., Boulerice, B., & Swisher, R. (2005). Multilevel correlates of childhood physical aggression and prosocial behaviour. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(5), 565-578.

- Roosa, M. W., Jones, S., Tein, J.-Y., & Cree, W. (2003). Prevention science and neighbourhood influences on low-income children's development: Theoretical and methodological issues. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 55-72.

- Shumow, L., Vandell, D. L., & Posner, J. (1998). Perceptions of danger: A psychological mediator of neighborhood demographic characteristics. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(3), 468-478.

- Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modelling. London: Sage.

- Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290-312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Soloff, C., Lawrence, D., Misson, S., Johnstone, R., & Slater, J. (2006). Wave 1 weighting and non-response. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Trewin, D. (2004). Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes For Area's (SEIFA) Australia 2001 (Technical Paper, Cat. No. 2039.0.55.001). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Vinson, T. (2007). Dropping off the edge: The distribution of disadvantage in Australia. Richmond, Vic.: Jesuit Social Services and Catholic Social Services Australia.

- Xue, Y., Leventhal, T., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Earls, F. J. (2005). Neighbourhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 554-563.

Appendix A

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperactivity | 3.51 | 2.29 |

| Emotional symptoms | 1.70 | 1.68 |

| Peer problems | 1.67 | 1.56 |

| Child's age (months) | 56.91 | 2.64 |

| Weekly family income (A$) | 1,261 | 634 |

| Neighbourhood facilities | 2.93 | 0.56 |

| Neighbourhood safety | 3.23 | 0.64 |

| Neighbourhood cleanliness | 3.27 | 0.61 |

| Neighbourhood belonging | 3.65 | 0.63 |

| Percentage in neighbourhood that have moved in the last 5 years | 77.51 | 12.06 |

| Percentage in neighbourhood that were born in Australia | 45.44 | 8.91 |

| n | % | |

| Child is a girl | 2,446 | 49.10 |

| Child is of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin | 187 | 3.80 |

| At least one parent employed | 4,395 | 88.20 |

| Single-parent family | 647 | 13.00 |

| At least one parent born overseas | 2,271 | 45.60 |

| Maternal education | ||

| Year 7 or 8 | 97 | 1.90 |

| Year 9 | 132 | 2.60 |

| Year 10 | 497 | 10.00 |

| Year 11 | 316 | 6.30 |

| Year 12 | 739 | 14.80 |

| Certificate | 1,234 | 24.80 |

| Advanced diploma | 441 | 8.90 |

| Bachelor degree | 802 | 16.10 |

| Graduate diploma | 312 | 6.30 |

| Postgraduate degree | 294 | 5.90 |

| Other | 60 | 1.20 |

| Physical disorder | ||

| Well-kept | 1,215 | 24.40 |

| Badly deteriorated/poor or fair condition | 3,526 | 70.80 |

| No houses nearby | 162 | 3.30 |

| Remoteness a | ||

| Highly accessible | 2,702 | 54.73 |

| Accessible | 1,163 | 23.56 |

| Moderately accessible | 856 | 17.33 |

| Remote and very remote | 216 | 4.43 |

| Neighbourhood socio-economic status b | ||

| Most disadvantaged | 638 | 12.80 |

| 2nd quintile | 538 | 10.80 |

| 3rd quintile | 960 | 19.30 |

| 4th quintile | 1,459 | 29.30 |

| Most advantaged | 1,388 | 27.90 |

Note: a Although these variables occur at the neighbourhood level, the number of postcodes in each category are not presented. Instead, the data reflect the number of children who reside in each of the area categories. b The neighbourhood quintiles are based on all Australian postcodes and not just the postcodes included in the LSAC sample, hence the unequal numbers of children in each quintile.

| Fixed coefficients | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | |

| Intercept | 5.47*** | .86 | 4.63*** | .88 | 4.64*** | .98 |

| Level 1: Family | ||||||

| Child's age (months) | -0.02* | .01 | -0.02* | .01 | -0.03* | .01 |

| Child is a girl | -0.82*** | .07 | -0.83*** | .07 | -0.82*** | .07 |

| Child is of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin | 0.44** | .17 | 0.41** | .17 | 0.38* | .17 |

| Single-parent family | -0.02 | .13 | -0.03 | .13 | -0.14 | .14 |

| At least one parent employed | -0.31** | .14 | -0.28* | .14 | -0.18 | .13 |

| At least one parent born overseas | -0.04 | .08 | -0.05 | .08 | -0.01 | .08 |

| Family income × 10 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Education (ref. = postgraduate) | ||||||

| Year 7 or 8 | 0.74* | .31 | 0.73* | .31 | 0.70 | .38 |

| Year 9 | 0.75** | .31 | 0.75** | .24 | 0.65** | .27 |

| Year 10 | 0.79*** | .16 | 0.75*** | .16 | 0.69*** | .18 |

| Year 11 | 0.63*** | .18 | 0.61*** | .18 | 0.53** | .20 |

| Year 12 | 0.60*** | .14 | 0.61*** | .14 | 0.46** | .16 |

| Certificate | 0.56*** | .13 | 0.52*** | .13 | 0.42** | .14 |

| Advanced diploma | 0.10 | .16 | 0.09 | .16 | 0.04 | .16 |

| Bachelor's degree | -0.16 | .14 | -0.16 | .14 | -0.23 | .15 |

| Graduate diploma | 0.02 | .17 | 0.02 | .17 | 0.07 | .18 |

| Other | 0.68 | .35 | 0.66 | .35 | 0.77* | .37 |

| Neighbourhood facilities | - | - | -0.01 | .01 | 0.00 | .01 |

| Neighbourhood safety | - | - | -0.16* | .08 | -0.10 | .09 |

| Neighbourhood cleanliness | - | - | -0.15 | .08 | -0.04 | .08 |

| Neighbourhood belonging | - | - | - | - | -0.35*** | .07 |

| Physical disorder (ref. = well-kept) | ||||||

| Bad/poor/fair | -0.02 | .08 | -0.03 | .08 | -0.06 | .08 |

| No houses nearby | 0.08 | .19 | 0.02 | .20 | 0.14 | .22 |

| Level 2: Neighbourhood | ||||||

| % moved in last 5 years | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .01 | 0.00 | .01 |

| % born in Australia | 0.00 | .01 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .01 |

| Remoteness (ref. = highly accessible) | ||||||

| Accessible | 0.17* | .08 | 0.15 | .09 | 0.17 | .10 |

| Moderately accessible | 0.16 | .10 | 0.14 | .10 | 0.17 | .11 |

| Remote or very remote | 0.02 | .17 | 0.00 | .17 | -0.01 | .19 |

| Neighbourhood SES (ref. = most advantaged) (χ(4) = 9.94, p < .05) | ||||||

| Most disadvantaged | 0.33* | .14 | 0.26 | .14 | 0.30* | .15 |

| 2nd quintile | 0.31* | .13 | 0.26* | .13 | 0.24 | .15 |

| 3rd quintile | 0.24* | .11 | 0.20 | .11 | 0.11 | .12 |

| 4th quintile | 0.09 | .09 | 0.06 | .09 | 0.00 | .10 |

| Variance components | ||||||

| Level 1 Variance | 4.74*** | .95 | 4.71*** | .10 | 4.67*** | .10 |

| Level 2 Variance | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Deviance | 19,874.24 | 19,758.59 | 16,784.07 | |||

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

| Fixed coefficients | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | |

| Intercept | 2.22*** | .66 | 1.94*** | .70 | 1.39 | .73 |

| Level 1: Family | ||||||

| Child's age (months) | 0.00 | .01 | 0.00 | .01 | 0.00 | .01 |

| Child is a girl | -0.05 | .05 | -0.06 | .05 | -0.04 | .05 |

| Child is of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin | 0.53*** | .16 | 0.53*** | .16 | 0.35 | .18 |

| Single parent family | -0.03 | .09 | -0.03 | .09 | -0.14 | .10 |

| At least one parent employed | -0.25* | .11 | -0.22* | .11 | -0.32* | .12 |

| At least one parent born overseas | 0.02 | .06 | 0.02 | .06 | 0.02 | .06 |

| Family income × 10 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Education (ref. = postgraduate) | ||||||

| Year 7 or 8 | 0.34 | .25 | 0.31 | .25 | 0.24 | .30 |

| Year 9 | -0.02 | .19 | -0.02 | .19 | 0.05 | .22 |

| Year 10 | 0.14 | .13 | 0.13 | .13 | 0.17 | .14 |

| Year 11 | 0.08 | .14 | 0.07 | .14 | 0.03 | .15 |

| Year 12 | -0.09 | .12 | -0.09 | .12 | -0.06 | .13 |

| Certificate | 0.02 | .11 | -0.01 | .11 | -0.02 | .12 |

| Advanced diploma | -0.10 | .12 | -0.10 | .12 | -0.08 | .13 |

| Bachelor's degree | -0.06 | .11 | -0.06 | .11 | -0.09 | .11 |

| Graduate diploma | -0.16 | .13 | -0.16 | .13 | -0.18 | .14 |

| Other | -0.27 | .23 | -0.29 | .23 | -0.31 | .24 |

| Neighbourhood facilities | - | - | 0.00 | .01 | 0.00 | .01 |

| Neighbourhood safety | - | - | -0.14* | .06 | -0.11 | .07 |

| Neighbourhood cleanliness | - | - | 0.00 | .06 | 0.07 | .07 |

| Neighbourhood belonging | - | - | - | - | -0.24*** | .05 |

| Physical disorder (ref. = well-kept) | ||||||

| Bad/poor/fair | 0.06 | .06 | 0.06 | .06 | 0.03 | .06 |

| No houses nearby | -0.07 | .14 | -0.10 | .14 | -0.11 | .15 |

| Level 2: Neighbourhood | ||||||

| % moved in last 5 years | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .01 | 0.00 | .00 |

| % born in Australia | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Remoteness (ref. = highly accessible) | ||||||

| Accessible | 0.15* | .06 | 0.15* | .06 | 0.14* | .07 |

| Moderately accessible | 0.06 | .07 | 0.06 | .07 | 0.04 | .08 |

| Remote or very remote | 0.17 | .13 | 0.18 | .13 | 0.14 | .14 |

| Neighbourhood SES (ref. = most advantaged) (χ(4) = 9.94, p < .05) | ||||||

| Most disadvantaged | 0.33* | .11 | 0.31** | .11 | 0.26* | .12 |

| 2nd quintile | 0.15 | .11 | 0.15 | .11 | 0.10 | .12 |

| 3rd quintile | 0.15 | .09 | 0.13 | .09 | 0.06 | .09 |

| 4th quintile | 0.01 | .07 | 0.01 | .07 | -0.01 | .07 |

| Variance components | ||||||

| Level 1 Variance | 2.65*** | .09 | 2.65*** | .09 | 2.62*** | .08 |

| Level 2 Variance | 0.03 | .05 | 0.02 | .05 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Deviance | 17,269.03 | 17,166.13 | 14,552.83 | |||

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

| Fixed coefficients | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | |

| Intercept | 2.97*** | .57 | 2.40*** | .61 | 2.13*** | .64 |

| Level 1: Family | ||||||

| Child's age (months) | -0.01 | .01 | -0.01 | .01 | -0.02* | .01 |

| Child is a girl | -0.24*** | .05 | -0.25*** | .05 | -0.32* | .15 |

| Child is of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin | 0.41** | .13 | 0.41** | .13 | 0.32* | .15 |

| Single parent family | -0.05 | .09 | -0.06 | .09 | -0.17 | .10 |

| At least one parent employed | -0.21* | .09 | -0.17 | .10 | -0.27* | .11 |

| At least one parent born overseas | 0.17*** | .05 | 0.17*** | .05 | 0.14* | .06 |

| Family income × 10 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Education (ref. = postgraduate) | ||||||

| Year 7 or 8 | 0.63** | .21 | 0.59** | .21 | 0.48 | .25 |

| Year 9 | 0.28 | .18 | 0.28 | .18 | 0.10 | .18 |

| Year 10 | 0.45*** | .11 | 0.44*** | .11 | 0.49*** | .13 |

| Year 11 | 0.23 | .13 | 0.20 | .13 | 0.18 | .14 |

| Year 12 | 0.10 | .10 | 0.10 | .10 | 0.10 | .11 |

| Certificate | 0.21* | .09 | 0.17 | .09 | 0.18 | .10 |

| Advanced diploma | -0.04 | .11 | -0.05 | .11 | -0.04 | .11 |

| Bachelor's degree | 0.02 | .10 | 0.02 | .10 | 0.02 | .10 |

| Graduate diploma | -0.02 | .11 | -0.03 | .11 | -0.01 | .12 |

| Other | 0.06 | .23 | 0.02 | .23 | 0.08 | .24 |

| Neighbourhood facilities | - | - | -0.01 | .01 | 0.00 | .01 |

| Neighbourhood safety | - | - | -0.21*** | .05 | -0.15* | .06 |

| Neighbourhood cleanliness | - | - | -0.03 | .06 | -0.01 | .06 |

| Neighbourhood belonging | - | - | - | - | -0.30*** | .04 |

| Physical disorder (ref. = well-kept) | ||||||

| Bad/poor/fair | 0.08 | .06 | 0.07 | .05 | 0.06 | .06 |

| No houses nearby | -0.03 | .12 | -0.06 | .12 | -0.02 | .13 |

| Level 2: Neighbourhood | ||||||

| % moved in last 5 years | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| % born in Australia | -0.01* | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Remoteness (ref. = highly accessible) | ||||||

| Accessible | 0.06 | .06 | 0.04 | .06 | 0.05 | .06 |

| Moderately accessible | -0.05 | .06 | -0.08 | .07 | -0.05 | .07 |

| Remote or very remote | -0.14 | .12 | -0.16 | .12 | -0.21 | .12 |

| Neighbourhood SES (ref. = most advantaged) (χ(4) = 9.94, p < .05) | ||||||

| Most disadvantaged | 0.44*** | .10 | 0.38*** | .10 | 0.34*** | .10 |

| 2nd quintile | 0.40*** | .09 | 0.36*** | .09 | 0.30*** | .09 |

| 3rd quintile | 0.30*** | .08 | 0.26*** | .08 | 0.20** | .08 |

| 4th quintile | 0.16** | .06 | 0.14* | .06 | 0.12 | .07 |

| Variance components | ||||||

| Level 1 Variance | 2.24*** | .06 | 2.22*** | .06 | 2.18*** | .07 |

| Level 2 Variance | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Deviance | 16,473.39 | 16,351.44 | 13,855.59 | |||

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Appendix B

Statistical analysis*

Conventional statistical techniques such as multiple regression assume that children's outcomes in one family are independent of those of children in another family. However, as the LSAC study sampled multiple children from the same postcodes, children who live in the same postcode are likely to have more similar outcomes than children residing in different postcodes. The degree of similarity in children's outcomes in the same postcode affects the accuracy of the results obtained from many statistical techniques.

Multilevel models (also referred to as linear random effect regression models, mixed models, random coefficient models and hierarchical linear models) are one way to obtain accurate estimates of the effect of neighbourhood disadvantage on children's outcomes, as they control for similarities in children's responses due to living in the same postcode (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). As children reside within neighbourhoods (postcodes), the multilevel models partition the variation in children's scores on the outcome indices into the family level (Level 1) and the neighbourhood level (Level 2). This enables accurate estimation of the determinants (e.g., neighbourhood disadvantage or child's gender) of children's outcomes.

In this context, Level 1 variables were those whose values varied between children and their families within the same postcode (e.g., gender and parental perceptions of the neighbourhood). Level 2 variables were those variables that had the same value for each child and their family within the same neighbourhood (e.g., neighbourhood socio-economic status).

As a preliminary step, we ran a model with no predictor variables, as this partitioned the variability in outcomes into the between- and within-neighbourhood proportions. An intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) for the percentage of variance between neighbourhoods was then calculated (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). The higher the level of the ICC, the more residing in that neighbourhood explains the outcomes.

To enable the results from statistical analyses to be generalised to Australian children, population sampling weights (for details, see Soloff et al., 2006) were also implemented in the multilevel models, using techniques outlined by Pfeffermann, Skinner, Holmes, Goldstein and Rasbash (1997). In this paper, multilevel models were run in MLwiN (Rasbash et al., 2004), which uses iterative generalised least squares (IGLS), a maximum likelihood procedure to provide model estimates.

As many of the neighbourhood variables were categorical (e.g., neighbourhood socio-economic status, remoteness, and physical disorder), multiparameter tests were employed to test the overall significance by improving the model fit. The deviance statistic is used to assess improvements in model fit (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). The difference in the deviances between the multilevel model without the categorical variable indicates the improvement in model fit resulting from the inclusion of the categorical variable.

The significance of the fixed coefficients in linear random coefficient regression were tested by dividing the fixed coefficient by its standard error, which yielded a t-value (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). Fixed coefficients are the average relationship between a predictor variable (e.g., neighbourhood safety) and the outcome (e.g., children's hyperactivity). These coefficients are unstandardised. Fixed coefficients that vary between children and their families (e.g., child's gender or family income) are referred to as family level variables, βij. It should be noted that parental perceptions of the neighbourhood are family- level variables because they vary across families within the same neighbourhood. Predictor variables that only vary across neighbourhoods, such as neighbourhood socio-economic status, are referred to as neighbourhood level variables, βj. There are also two variance components for each linear random coefficient regression. One variance component represents the variation in children's scores (e.g., hyperactivity) at the family level, eij. The other variance component provides information on the variation in children's scores at the neighbourhood level, uj.

According to Baron and Kenny (1986) the criteria for statistical mediation are when: (a) the independent variable (e.g., neighbourhood safety) is significantly associated with the mediator (e.g., neighbourhood belonging);

(b) the independent variable is significantly associated with the dependent variable (e.g., children's hyperactivity) when the mediator is not present; (c) the mediator is significantly associated with the dependent variable; and (d) the association of the independent variable with the dependent variable is attenuated when the mediator is added to the model. Sobel tests (Sobel, 1982) are a formal method of testing for statistical mediation and were used in the current study.

Cases with missing data were deleted from the analyses. The deletion of missing data did not affect any substantive conclusions from the analyses, as 90% of cases had complete data and the population weights adjusted for factors that influenced non-response (Soloff et al., 2006).

* This appendix is adapted from Edwards and Bromfield (2009).

Edwards, B. & Bromfield, L. (2010). Neighbourhood influences on young children's emotional and behavioural problems. Family Matters, 84, 7-19.