Starting school

A pivotal life transition for children and their families

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

September 2012

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

All children arrive at primary school with knowledge and experiences from growing up within the context of family, neighbourhood, service and community environments. Traditional concepts of school readiness have placed emphasis on a child's skills; however, preschool skill-based assessments of children's functioning have been shown to be poor predictors of subsequent school adjustment and achievement (La Paro & Pianta, 2001; Pianta & La Paro, 2003). More recent thinking about the transition to school recognises that "school readiness does not reside solely in the child, but reflects the environments in which children find themselves" (Kagan & Rigby, 2003, p. 13).

Starting primary school is a crucial event for young children and their families as they transition from home learning environments and early childhood education programs - such as child care, preschool or kindergarten - into the more formal school environment (Centre for Community Child Health, 2008). How well children are prepared for this transition is important, as it affects their long-term outcomes (Centre for Community Child Health, 2008; Dockett, Perry, & Kearney, 2010).

The transition to school is more than just what schools do to "orient" children and their families to the school, often characterised by presenting information to parents and children (Dockett & Perry, 2001). Rather, the transition to school can be thought of as a process that starts years before children actually commence school and continues well after they have started (Dockett & Perry, 2007). This process can be thought of in ecological terms (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), recognising that children's families and social networks are and remain significant influences throughout childhood, but as children move from the home to other learning environments - such as early childhood education and care (ECEC) - these environments become increasingly important in children's learning and development. Additionally, the larger social structure and economic, political and cultural environments affect the resources available to families and children, and the character of the communities in which children live, including the economic climate and accessibility of appropriate services, has significant influence on their development (Sanson et al., 2002).

This ecological perspective has contributed to the re-conceptualisation of the nature of "school readiness" and of how best to promote effective transitions to school. School readiness is now conceptualised (and can be measured) as four connected and essential components (Emig, Moore, & Scarupa, 2001) and has been represented as an equation: ready families + ready communities + ready early childhood services + ready schools = ready children (Kagan & Rigby, 2003; Rhode Island KIDS COUNT, 2005).

The first component takes into account the capacity of families, including the home learning environment they provide for children. The second component, the capacity of communities, refers to the resources available within communities to support families with young children. The third is the early years service environments available to children and the importance of high-quality developmental opportunities for young children for supporting school readiness (Emig et al., 2001). Research points, for example, to the value of having high-quality preschools for enhancing the overall development of children, with significant benefits for those from disadvantaged backgrounds (Magnuson, Ruhm, & Waldfogel, 2007; Melhuish, 2003; Sammons et al., 2007; Siraj-Blatchford & Woodhead, 2009; Sylva, Melhuish, Sammons, Siraj-Blatchford, & Taggart, 2004, 2010). The fourth component is how ready the school is for children. This includes the ability of schools to adapt their structure and learning environments to take into account the individual differences and needs of children, as well as their ability to support and engage families in supporting their children's transition and learning.

It is the interaction between and cumulative effect of all of these influences that determines the extent to which children enter school ready and able to take advantage of the learning, development and social opportunities that schools provide.

This paper focuses on transitions to school from the perspective of measuring and understanding the process and impact of the transition to school for children and their families, as well as looking at promising approaches to supporting optimal transitions to school for children and their families.

Measuring and understanding the process and impact of the transition to school for children and their families

Until recently in Australia, process and impact indicators of the transition to school for children and their families have not been available. However, two important initiatives to develop this knowledge have been the Australian Early Development Index (AEDI) and the Outcomes and Indicators of a Positive Start to School: Development of Framework and Tools research project.

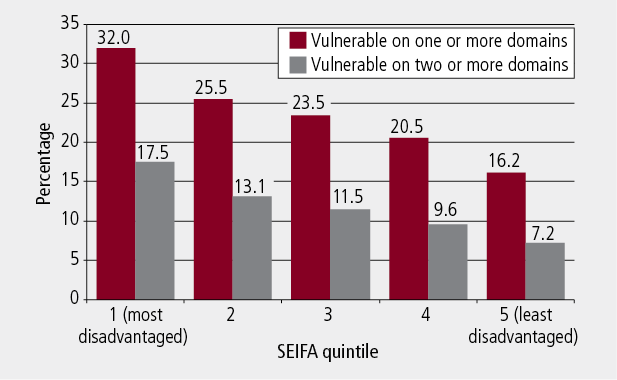

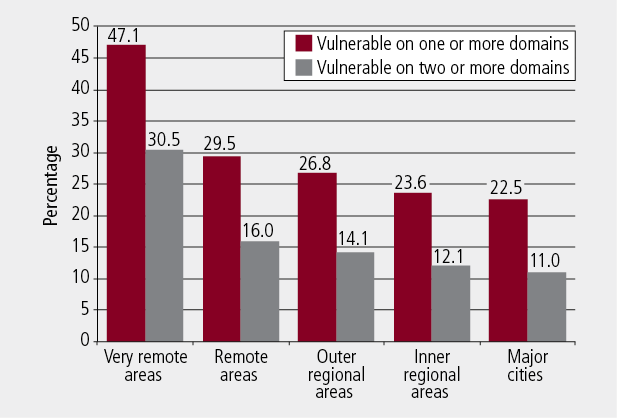

The Australian Early Development Index

The AEDI is an adapted and validated version (Brinkman et al., 2007; Goldfeld, Sayers, Brinkman, Silburn, & Oberklaid, 2009) of the Canadian Early Development Instrument (Janus, Brinkman, & Duku, 2011; Janus & Offord, 2007), trialled and evaluated in 60 communities across Australia between 2004 and 2007 (Sayers et al., 2007). The AEDI is a population measure from a teacher-completed checklist of young children's development. The AEDI measures five key areas, or domains, of early childhood development: physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills (school-based), communication skills and general knowledge. Data are collected nationally every three years for about 270,000 children in their first year of full-time school to report at community, state and national levels. In order to examine socio-economic variations, the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA)1 was attributed to the communities in which children lived. The first national implementation of the AEDI was in 2009 (n = 261,142 children in the first year of full-time school).2 The results showed that 23.6% of Australian children were developmentally vulnerable on one or more domains, and 11.8% of children were developmentally vulnerable on two or more domains. There were higher proportions of such developmentally vulnerable children living in the most socio-economically disadvantaged communities (Figure 1) and in very remote areas of Australia (Figure 2) (Centre for Community Child Health & Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 2009).

Figure 1: Level of children's developmental vulnerability, by area of relative disadvantage, 2009

Source: AEDI 2009

Figure 2: Level of children's developmental vulnerability, by remoteness of geographic location, 2009

Source: AEDI 2009

Demographic information captured in the AEDI found that teachers reported 11,484 children (4.4%) as having additional or special needs previously diagnosed and requiring additional assistance (Goldfeld, O'Connor, Sayers, Moore, & Oberklaid, 2012). Three-quarters of these children were identified as having more than one area of difficulty (n = 7,686, 75%).3 Although they had been previously diagnosed, teachers reported that nearly half of the children with additional needs (n = 4,822, 42%) would benefit from further assessment. Only half of the children with additional needs (n = 5,590, 56.2%) were reported to have attended an early intervention program. An additional 46,938 (18%) children were considered to have developmental concerns. This included 36,195 (14.6%) children who were not reported as having diagnosed special needs but were identified by teachers as experiencing some areas of impairment (Goldfeld et al., 2012).

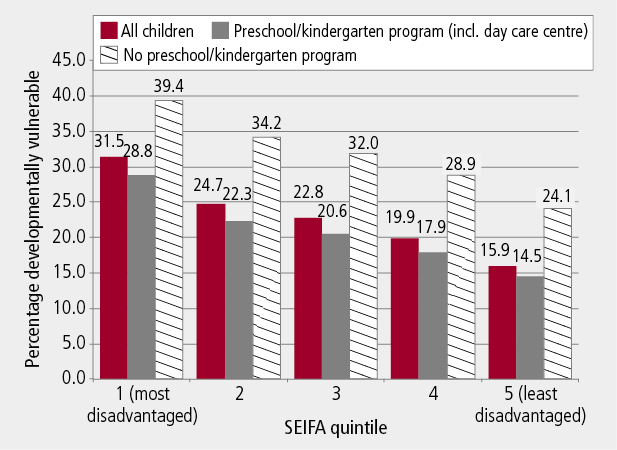

Teachers completing the AEDI in 2009 reported 65.1% of children attended a preschool program, and 35.7% attended a day care centre, of which 24.8% were in a day care setting with a preschool program4 (Sayers, Moore, Brinkman, & Goldfeld, 2012). Overall, 80.9% of Australian children were reported to have attended a formal preschool program or a preschool program in a day care setting.5 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and language background other than English (LBOTE) children (not mutually exclusive) had lower rates of preschool program participation in the year before entering school, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children reported as having the lowest rates of participation in preschool compared to all other children. Furthermore, it was found that children who attended preschool (including in a day care centre) had lower rates of developmental vulnerability on one or more domains of the AEDI than children who had not attended preschool, regardless of the level of area disadvantage (Figure 3). Similarly, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and LBOTE children had lower rates of developmental vulnerability if they had attended preschool (Sayers et al., 2012).

The results from the AEDI national survey highlight that significant numbers of children arrive at school with developmental vulnerability and additional needs that schools need to take into account when planning to be "ready" for children's transition to school.

While the AEDI results provide important information that can be used by teachers, schools and communities for planning (Sayers et al., 2007; Sayers, Mithen, Knight, Camm, & Goldfeld, 2011), the results are not currently a useful measure of the transition to school process from the child, family, early childhood service and school perspective. An initiative aiming to measure the transition-to-school process from those perspectives is the Outcomes and Indicators of a Positive Start to School: Development of Framework and Tools research project.

Figure 3: Proportion of children who were developmentally vulnerable on one or more AEDI domains, by preschool participation and area of relative disadvantage, 2009

Note: Excludes children where the teacher did not know the early childhood education or other type of informal care experience of the child.

Source: AEDI, 2009

Outcomes and Indicators of a Positive Start to School

The aim of the Outcomes and Indicators of a Positive Start to School: Development of Framework and Tools research project was to examine the application of an outcomes measurement of a positive transition to school (West & Nolan, 2012). The main objectives were to:

- develop outcome-focused data collection and monitoring tools to measure the outcomes and indicators of a positive start to school for children, parents/families and early childhood and school educators; and

- test the validity of these newly developed data collection tools, including an investigation of whether these tools would be applicable and inclusive of all children; in particular, families with an Indigenous or culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background or who have a child with a disability.

The research was informed by evidence of the importance of parents and early childhood educators for effective transitions to school. While it is worth noting that there are other potential sources of information about children's transition to school, such as the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children and the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children, the aim of this research was to develop survey tools that could in the future provide local data to communities and schools to plan for optimal transitions for children from the early years to school. Comprehensive tools that apply authentic techniques for measuring transition to school outcomes have not previously been available; however, it has been established that best practice would involve "those individuals that know the child best, their parents and teachers" (Bagnato, 2007, p. 246). Additionally, leading international researchers call for children themselves, as active agents in the transition process, to be consulted on their experiences (rather than be assessed for skill level) (Educational Transitions and Change Research Group, 2011). From this, and in line with the "ready children" equation (Kagan & Rigby, 2003; Rhode Island KIDS COUNT, 2005), the key informants for measuring transitions to school were determined to be children, parents, early childhood educators and teachers.

The outcomes measured by the research project are outlined in Box 1 and were based on a framework developed by an earlier project commissioned by the Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) (Nolan et al., 2009).

The research methodology involved three stages:

- Stage 1 - The development of the four surveys with theoretical input and expert endorsement. The four tools were: an Early Childhood Educator Survey, a Prep Teacher Survey, a Parent Survey and a Child Survey.

- Stage 2 - Trialling the surveys with children (n = 208), parents (n = 227, matched to child) and educators (n = 210 primary teacher and 95 early childhood educator surveys, matched to the child, plus an additional 37 early childhood educator and primary teacher surveys not linked to child and parent surveys) across 19 communities in Victoria. Additional consultations and focus groups were held with parents of Indigenous and CALD children and parents of children with a disability.

- Stage 3 - Analysis of the trial results to build knowledge on the psychometric properties, inclusiveness, accessibility and administration of the tools.

Box 1: Outcomes of a positive start to school

- Children feel safe, secure and supported in the school environment.

- Children display social and emotional resilience in the school environment.

- Children feel a sense of belonging to the school community.

- Children have positive relationships with educators and other children.

- Children feel positive about themselves as learners.

- Children display dispositions for learning.

- Families have access to information related to the transition to school tailored to suit the family.

- Families are involved with the school.

- Relationships between families and the school are respectful, reciprocal and responsive.

- Educators are prepared and confident that they can plan appropriately for the children starting school.

Source: Nolan et al. (2009)

The psychometric analysis found the three adult surveys to be accurate and reliable measures of a successful transition to school. For each outcome/indicator in each survey, the contribution of each question to that outcome/indicator, and possible redundancy of items, was investigated using Cronbach's alpha.6 Most items in the questionnaires (all items in the child questionnaire) used Likert scales. In order to include the non-Likert scale questions in the analyses, Cronbach's alpha using standardised scores were calculated. While the internal consistency of the child survey was questioned, children were found to engage in the measure and the child survey was found to have a degree of reliability. These findings, combined with the research advocating for the ecological measurement of the transition to school, provide grounds for further trialling of the child survey.

Further to this, respondents perceived the information collected by the surveys to be useful, and largely comprehensive of the transition experience. Feedback from respondents indicated the four tools were perceived as being inclusive of the general population. However, questions were raised around how inclusive they were of specific subpopulations, including CALD families, Indigenous families, families with low literacy and families of children with a disability. Minor modifications, such as simplifying wording, were recommended to increase inclusivity.

CALD and Indigenous parents found the surveys easy to complete, but the concepts behind the questions were not well understood by some. This suggests further work is needed to break down some of the concepts in the survey.

Recommendations arising from the research included the revision of each tool in order to increase validity and reliability, improve the accessibility of the tools to all participant groups, increase inclusivity, and enhance respondent participation. Once modified, the revised tools will require further testing in order to understand how well they operate.

While this research has added to our understanding of how to measure the outcomes and indicators of a positive transition to school, successful indicators need to be more than technically sound; they need to produce data that are useful for the end user (Holden, 2009). It will be important that future testing of the revised tools includes opportunities to explore the usefulness of the survey results. This could be done by providing the results to schools in a useable format and in a timeframe that supports schools to make changes for the following year. Linkage to other datasets, such as the AEDI, will also assist policy-makers, schools and early childhood educators to understand the changes needed and to know whether their efforts are contributing to changed outcomes over time.

The AEDI and the Outcomes and Indicators of a Positive Start to School: Development of Framework and Tools research project provide promising ways of measuring and understanding the transition-to-school process and children's development. While providing these types of data at a local level will assist communities to determine priorities for change, and support families' and children's seamless transition, knowledge of effective strategies that can be undertaken by schools, early years services and communities is also required.

Promising approaches to supporting optimal transitions to school for children and their families

The two case studies presented below are developing evidence around the effectiveness of tools, resources and approaches to support the transition to school by practically applying the reconceptualised notion of school readiness through community-led efforts and Victorian State Government policy changes. These are the Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative, with associated policies, and the Linking Schools and Early Years (LSEY) project. Lessons from these two case examples provide an impetus for early years services, schools, communities and policy-makers to explore how such approaches and resources can be effectively implemented in communities more broadly.

Case study 1: Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative

In November 2009, the Victorian DEECD implemented the Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative across the state. The Transition initiative aimed to improve children's experience of starting school by strengthening the development and delivery of transition programs. It acknowledged that transition is not a point-in-time event, but rather an experience that starts well before, and extends far beyond, the first day of school, involving and affecting children, families and educators at services and schools.

The Transition initiative was a key element of the Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework, which supported all early childhood professionals to work together and with families to achieve common outcomes for all children, thereby advancing all children's learning and development, from 0 to 8 years. This framework recognised that when children experience learning opportunities that are responsive to their strengths, interests, cultures and abilities, and build on their previous experiences, their learning and development is enhanced. Consequently, successful transition to school relies on children, families, early childhood and school professionals developing positive and supportive relationships (DEECD, 2009). Relationships that support information-sharing between children, families and educators ensure that the continuity of each child's learning and development can be supported and planned for prior to arriving at school.

The Transition initiative was a multi-faceted approach that provided a suite of resources, professional development and supports for early childhood services, schools, outside-school-hours care services and parents to share information that will support a positive transition to school for all children. A key component of the Transition initiative was the Transition Learning and Development Statement, a tool for families and educators to share information that also captures the child's voice as a critical person in the process of moving to a formal school environment.7

To inform the development of the Transition initiative and resources, the following was undertaken:

- a literature review - drawn from national and international research concerning children's transition to school (Centre for Equity and Innovation in Early Childhood, 2008);

- thirty transition pilots - funded to inform government policy and expand the local evidence base regarding what works in supporting children's transition to school;

- statewide consultation - undertaken in tandem with the development of the national and Victorian frameworks to ensure a common language was developed; and

- an evaluation of the transition pilots - an embedded feature of the initiative (Astbury, 2009) that identified ten promising practices to support the transition to school (see Box 2).

Box 2: Ten promising practices that support the transition to school

- Reciprocal visits for children across early years services and schools.

- Reciprocal visits for educators across early years services and schools.

- Transfer of information via transition statements and meetings.

- Joint professional development for early childhood professionals and school staff.

- Local transition networks that involve a broad range of stakeholders.

- Buddy programs for children starting schools, as well as parent groups.

- Family involvement strategies, tailored to meet the needs of families attending early childhood services or schools.

- Developmentally appropriate educational practices, also commonly referred to as "play-based learning".

- The use of social story boards for children.

- Community-level transition plans and timetables.

In 2010, an independent evaluation of the Transition initiative in its first full year of implementation was conducted (SuccessWorks, 2010). Recommendations from this evaluation informed the refinement to the Transition Learning and Development Statement and resources. Other recommendations pointed to further clarification and information on the underpinning strength-based approach to the transition to school.

Finally, DEECD conducted a follow-up evaluation in 2011 to determine how specific groups - early childhood professionals, prep teachers8 and outside-school-hours care services - engaged with the Transition initiative in its second year (DEECD, 2011). Highlights of the results include:

- almost all prep teachers (96%) read the statements;

- the vast majority of prep teachers (up to 91%) considered all sections of the statements valuable and found that they helped support a positive start to school for children;

- early childhood professionals reported that the time spent writing the statements was an improvement on the previous year; and

- not all OSHC services were aware of the statements and fewer actually received them, even though many OSHC services are located on school grounds and are involved in transition-to-school programs and activities.

Other interesting findings pointed to the development of stronger relationships between early childhood and school professionals as a result of the statements, and that early childhood professionals valued acknowledgement and feedback as a way of improving the quality of information provided to prep teachers. An ongoing research agenda is being implemented.

Case study 2: Linking Schools and Early Years project

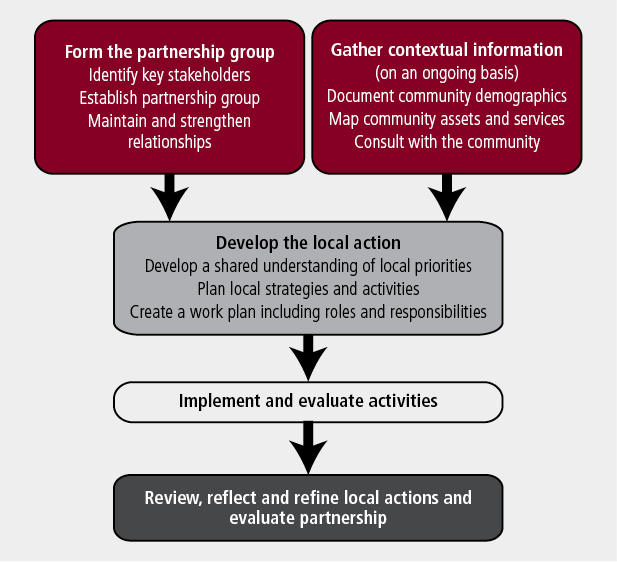

The Linking Schools and Early Years project was developed based on research and around the premise that "barriers faced by vulnerable children when starting school may be overcome by stronger linkages and partnerships between schools, early years services, families and the community" and that there is potential for this to ensure better planning for the individual needs of children entering school (Centre for Community Child Health, 2006, p. 22). As a result, the LSEY project has been implemented within a "place-based community partnership" framework that aims to reconceptualise how early childhood services and schools work in partnership with children, families and each other as a 0-8 years early childhood service system to provide a continuum of support and learning for children. This approach has enabled three Victorian communities (Corio-Norlane in the City of Greater Geelong, Footscray in the City of Maribyrnong, and Hastings in the Mornington Peninsula Shire) to collaboratively lead planning and implementation of activities that respond to the needs of their specific community, context and place. In each LSEY community, planning and action has been led by a local partnership group and fall-out networks that include management and educators/practitioners from early childhood services, schools, child and family community services, and local and state government. These partnerships followed the process described in Figure 4.

Figure 4: A place-based community partnership approach

An external evaluation was built into the project from the outset and will add to Australian and international evidence around what contributes to a positive transition to school. The evaluation methodology has a cross-sectional design, and both quantitative and qualitative data have been collected at two (of three) points in time - 2008 and 2010 - with the third planned for 2012. Through self-administered questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, the evaluation provides evidence of improvements in family transition experiences, family engagement, responsive planning for children, and connections and partnerships between local services. The 2008 and 2010 LSEY evaluation reports are available online.9

A central theme of the LSEY project is the active involvement of parents in their children's early education and care, school environments and ongoing learning and development. The partnership approach, activities and external project evaluation findings to date are explored throughout this case study, framed around three project goals.

Goal 1: Children and families make a smooth transition between early years services and schools

The evaluation suggests that the LSEY project has demonstrated that effective relationships between early childhood education and care services, schools, and children and families, and a mutual understanding of everyone's role in children's learning and development, are pivotal in creating change to support a positive transition to school. "LSEY partnerships have fostered an improved understanding of the environments each organisation operates in as a result there is growing mutual respect between schools and ECEC services" (Eastman, Newton, Rajkovic, & Valentine, 2010, p. 39). The evaluation also showed that ECEC services and schools recognised the importance of showing "parents that there are positive relationships between schools and ECEC services to make the transition process more comfortable for families" (Eastman et al., 2010, p. 13). These cross-sectoral relationships provide an enabling environment for the development and implementation of consistent transition programs, resources and learning experiences across early education and care services, school programs and home learning environments.

Activities as a result of cross-sectoral relationships in the LSEY communities include:

- peer swaps - enabling early childhood and prep educators to spend time in each other's services and build a shared understanding of their respective roles in children's learning;

- community-wide transition programs - jointly planned and implemented by ECEC services and schools and incorporating informal and formal school orientation opportunities; and

- consistent transition information for families - collaboratively developed and distributed through transition calendars, information packs and school participation in early years events/expos, which enabled consistent information provision for families about the importance of transition programs.

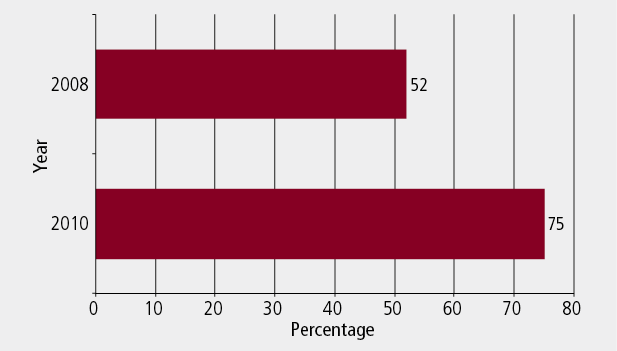

The LSEY evaluation reported that activities implemented by the LSEY communities, such as those outlined above, contributed to an 18% increase in children participating in transition-to-school programs, with 68% of children's transition experiences involving time at school over a number of days and weeks. This is consistent with the finding of an increase in the percentage of children visiting the school more than once before formally starting school (Eastman et al., 2010), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Proportion of children visiting school more than once before starting school, 2008 and 2010

Source: Eastman et al. (2010)

Goal 2: Early years services and schools actively engage families

Respectful and active partnerships between services and parents/carers underpin the LSEY approach and activities. Supporting parents to feel welcome and comfortable in their child's early learning and school environments is considered central to building their capacity and confidence to become partners in their child's long-term learning and development. Through reporting findings back to the LSEY communities, the evaluation has enabled the communities to create a local profile of family engagement and interaction with ECEC services and schools. This information has been used to inform a range of family engagement strategies, including but not limited to:

- creating welcoming environments - formal and informal opportunities for families to spend time in ECEC services and schools, including playgroups, social events, classroom participation, and information-sharing, interviews and information sessions regarding their child's educational program, many of which have been joint ECEC-school activities, which also support the transition to school;

- consultation with families - formal and informal feedback on ECEC service and school operations, programs and practices, and activity development. Family-friendly reviews have also taken place to explore how welcoming and comfortable ECEC and school environments are for families; and

- creating family friendly spaces - family spaces within ECEC services and schools, organised, decorated and facilitated by parents or facilitated by the school to gain greater engagement from families.

The evaluation results suggest that strategies implemented across the LSEY communities have contributed to the majority of parents reporting high levels of satisfaction with various aspects of ECEC service and school environments and interactions. Between 2008 and 2010, there was also an increase of parents participating in community/cultural events and in classroom activities with children (Eastman et al., 2010), as shown in Table 1.

| Activity | 2008 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Community/cultural events | 39% | 50% |

| Classroom activities | 19% | 33% |

Source: Eastman et al. (2010)

Goal 3: Schools are responsive to the individual needs of all children

The evaluation findings suggest that those LSEY project communities that demonstrate greater connections, effective communication and collaborative planning can enable tailored children's learning experiences. Project activities that work towards achieving this tailoring have included:

- sharing professional knowledge and planning together - joint professional development and forums to bring together the 0-8 early years profession in planning and professional learning, supporting the capacity for and value of collaborative planning approaches;

- creating mechanisms for sharing - information-sharing between ECEC services and schools to enable joint development of meaningful tools and processes, including common language tools and peer support for implementing Victorian government information-sharing tools within the LSEY partnership approach and a shared understanding of children's developmental strengths and needs; and

- improving quality of learning experiences - program planning between ECEC services and schools to collaboratively develop and deliver inquiry-based educational programs for ECEC and school settings. Local educators are also using other information and expertise from child and family services to help in planning for diverse and responsive learning experiences.

The evaluation reported an increase in schools exchanging information with ECEC services, from 43% of schools in 2008 to 63% in 2010 (Eastman et al., 2010). There was also a significant increase in the time that ECEC services, schools and child and family services spent together at the management and educator level. In 2008, no schools ran joint training/education sessions with ECEC services, but in 2010, 5 of the 11 schools in the evaluation (45%) did. Similarly, in 2008, no schools ran joint management planning exercises, but in 2010, 6 of the 11 schools (55%) did. Furthermore, in 2010, 75% of ECEC services had staff attend planning, training or information sessions organised by local child and family services, and 90% of ECEC services had staff attend planning, training or information sessions organised by local schools; an increase of 51% from 2008 (Eastman et al., 2010). The continually strengthening relationships within LSEY communities have contributed to significant increases in referrals and communication between ECEC services/schools and child and family services (Eastman et al., 2010), as shown in Table 2.

Children's early learning journey and transitions are supported by effective relationships between families, services and schools. The LSEY project's place-based community partnership approach has demonstrated that when communities work together to plan and implement strategies for children and families, local relationships strengthen and enable more effective and responsive support. As stakeholders in children's learning and development, communities are well placed to lead local service system change to support a positive transition to school that enables children to gain maximum benefit from all learning opportunities. At a broader community level, the LSEY approach has demonstrated that strong relationships and collaboration can result in effective community partnerships, and build capacity in educational practices and community leadership. It provides evidence to suggest that sustained partnerships and practice change can contribute to improved long-term outcomes for children and their families.

| Referrals | % increase from 2008 to 2010 |

|---|---|

| From ECEC services to child/family health and community services | 25% |

| From schools to child/family health and community services | 24% |

| From child/family health and community services to ECEC services | 33% |

| Communications | % increase from 2008 to 2010 |

| Between child/family health and community services and schools about particular families | 31% |

| Between child/family health and community services and families about ECEC services | 22% |

| Between child/family health and community services and families about schools | 15% |

Discussion

The AEDI and Outcomes and Indicators projects are tools for identifying children's developmental progress upon school entry, measuring the resources and approaches to coordinate supports for children and their families in the move to school, and supporting the evaluation of transition approaches. Both tools respond to an ecological framework of development.

The AEDI provides a powerful picture of children's developmental outcomes upon school entry. The information provides impetus for more responsive and preventative planning for children and further research in areas that can identify strategies and approaches to better support children in their early years and throughout their transition to school.

The Outcomes and Indicators research project provides more specific measures of how well children transition to school and the outcomes of the transition process from the perspectives of children, parents, early childhood educators and schools. Providing these data at a local level can support the capacity of communities to better plan the transition to school and enable outcome evaluations of local transition processes and initiatives implemented by communities and governments. However, further testing and validation of the survey instruments are required, as are processes for reporting the information to schools, early years services and community stakeholders.

The two case studies included in this paper describe strategies to facilitate positive school transitions for children and their families, and practical ideas that services across the early childhood to school continuum could implement to support transition. Evaluation of the case study strategies provides positive process findings, but not short- and long-term child outcome data because they are interventions within the service system to support practice in working with children, families and community. Notwithstanding, the case studies provide evidence-informed approaches and we suggest that, if implemented within a locally responsive framework, they are likely to lead to improved transition outcomes for children and families.

The Victorian Government's Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative goes statewide in addressing the aim of improving school transitions through development of tools and resources to share information about children's learning and development. Within the Victorian policy context, the LSEY project demonstrates how a place-based partnership can ensure transition processes and information exchanges are meaningful. The interaction between the policy- and community-led case studies demonstrates the importance of the place-based partnership framework to the effective implementation of government policy.

The two case studies tackle the structural and relational barriers to a positive school transition in Victoria, particularly local fragmentation in the service system, family engagement in school transition and collaboration among service providers. The LSEY project demonstrates that purposeful, place-based strategies that bring together school, early years and community service partners to plan and implement local practice change can improve process indicators of positive transitions to school.

In future, the AEDI and the Outcomes and Indicators projects have the potential to provide a comprehensive picture of children's development and experiences, and meaningful measures of the approaches and resources communities implement to support a positive transition to school for children and their families. In combination, these initiatives may help address the need for measures of how optimal transitions to school for children and their families may be supported at a local level. They may also provide tools to consider outcomes of projects such as LSEY and the Victorian Government's Transition initiative, and support an Australia-wide approach to measuring the effectiveness of the myriad approaches to the transition between early years and school.

Endnotes

1 SEIFA is a set of four indexes to allow ranking of regions/areas according to their levels of social and economic wellbeing. The data presented here uses the SEIFA Index of Relative Disadvantage. For more information about SEIFA, see <www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Seifa_entry_page>.

2 Community maps and profiles based on children's suburb or town of residence are available on the AEDI website <maps.aedi.org.au>.

3 This question was answered for 10,247 children (89.2% of those with identified additional needs).

4 Teachers were asked to base their information on enrolment records or information provided by parents. Children were excluded from the analysis if the teacher did not know the early childhood education or other type of informal care experience of the child (e.g., if they were cared for by a grandparent). This is in order to obtain a more accurate reflection of participation in a preschool or kindergarten program (including in a day care centre). If the teacher responded "don't know", the child may nevertheless have been in some form of education or care, therefore they are excluded from the analysis.

5 Children may have been in more than one type of early education program; for example, a preschool program and a day care with a preschool program.

6 Cronbach's alpha is a measure of internal consistency; that is, how closely related a set of items are as a group (Cronbach, 1951). A "high" value of alpha is often used as evidence that the items measure an underlying (or latent) construct.

7 In 2009, completion of the Transition Statement became DEECD policy and part of the criteria attached to state government funding for the provision of kindergarten for four-year-old children.

8 There is significant variation in starting school entry policies across Australian states and territories. The first year of full-time school (pre-Year 1) in Victoria is called the preparatory or "prep" year (Edwards, Taylor, & Fiorini, 2011).

9 See the website of the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne <www.rch.org.au/lsey/projects.cfm?doc_id=13221>.

References

- Astbury, B. (2009). Evaluation of Transition: A Positive Start to School pilots. Melbourne: University of Melbourne Centre for Program Evaluation.

- Bagnato, S. J. (2007). Authentic assessment for early childhood intervention: Best practices. New York: Guilford Press.

- Brinkman, S. A., Silburn, S. R., Lawrence, D., Goldfeld, S., Sayers, M., & Oberklaid, F. (2007). Construct and concurrent validity of the Australian Early Development Index. Early Education and Development, 18(3), 427-451.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Centre for Community Child Health. (2006). Linking Schools and Early Years Services final report. Melbourne: Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne.

- Centre for Community Child Health. (2008). Rethinking the transition to school: Linking Schools and Early Years Services (PDF 71 KB) (Policy Brief No. 11). Melbourne: Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. Retrieved from <www.rch.org.au/emplibrary/ccch/PB11_Transition_to_school.pdf>.

- Centre for Community Child Health & Telethon Institute for Child Health Research. (2009). A snapshot of early childhood development in Australia: AEDI National Report 2009. Canberra: Australian Government.

- Centre for Equity and Innovation in Early Childhood. (2008). Transition: A Positive Start to School: Literature review. Melbourne: University of Melbourne Centre for Equity and Innovation in Early Childhood.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334.

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. (2009). Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework: For all children from birth to eight years. Melbourne: DEECD.

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. (2011). Follow-up evaluation of the Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative. Melbourne: DEECD.

- Dockett, S., & Perry, B. (2001). Starting school: Effective transitions. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 3(2), 1-14.

- Dockett, S., & Perry, B. (2007). Transitions to school: Perceptions, expectations, experiences. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- Dockett, S., Perry, B., & Kearney, E. (2010). School readiness: What does it mean for Indigenous children, families, schools and communities? (Issues Paper No. 2). Melbourne: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- Eastman, C., Newton, B., Rajkovic, M., & Valentine, K. (2010). Linking Schools and Early Years project evaluation: Data collection round 2. Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales

- Educational Transitions and Change Research Group. (2011). Transition to school: Position statement. Albury-Wodonga, NSW: Research Institute for Professional Practice, Learning and Education, Charles Sturt University. Retrieved from <www.csu.edu.au/research/ripple/research-groups/etc/Position-Statement.pdf>.

- Edwards, B., Taylor, M., & Fiorini, M. (2011). Who gets the "gift of time" in Australia? Exploring delayed primary school entry. Australian Review of Public Affairs, 10(1), 41-60.

- Emig, C., Moore, A., & Scarupa, H. J. (2001). School readiness: Helping communities get children ready for school and schools ready for children (Child Trends Research Brief). Washington, DC: Child Trends.

- Goldfeld, S., O'Connor, M., Sayers, M., Moore, T., & Oberklaid, F. (2012). Prevalence and correlates of special health care needs in a population cohort of Australian children at school entry. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 33(4), 319-327. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e31824a7b8e

- Goldfeld, S., Sayers, M., Brinkman, S., Silburn, S., & Oberklaid, F. (2009). The process and policy challenges of adapting and implementing the Early Development Instrument in Australia. Early Education & Development, 20(6), 978-991.

- Holden, M. (2009). Community interests and indicator system success. Social Indicators Research, 92(3), 429-448.

- Janus, M., Brinkman, S. A., & Duku, E. K. (2011). Validity and psychometric properties of the Early Development Instrument in Canada, Australia, United States, and Jamaica. Social Indicators Research, 103(2), 283-297.

- Janus, M., & Offord, D. (2007). Development and psychometric properties of the Early Development Instrument (EDI): A measure of children's school readiness. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 39(1), 1-22.

- Kagan, S. L., & Rigby, D. E. (2003). Improving the readiness of children for school: Recommendations for state policy. Washington, DC: Centre for the Study of Social Policy.

- La Paro, K. M., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Predicting children's competence in the early school years: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 70(4), 443-484.

- Magnuson, K. A., Ruhm, C., & Waldfogel, J. (2007). Does prekindergarten improve school preparation and performance? Economics of Education Review, 26(1), 33-51.

- Melhuish, E. (2003). A literature review of the impact of early years provision on young children, with emphasis given to children from disadvantaged backgrounds. London, UK: National Audit Office.

- Nolan, A., Hamm, C., McCartin, J., Hunt., Scott, C., & Barty, K. (2009). Outcomes and Indicators of a Positive Start to School: Report prepared by Victoria University for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Melbourne: Victoria University.

- Pianta, R. C., & La Paro, K. M. (2003). Improving early school success. Educational Leadership, 60(7), 24-29.

- Rhode Island KIDS COUNT. (2005). Getting ready: Findings from the National School Readiness Indicators Initiative. A 17 state partnership. Providence, RI: Rhode Island KIDS COUNT.

- Sammons, P., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., Grabbe, Y., & Barreau, S. (2007). Effective Pre-School and Primary Education 3-11 Project (EPPE 3-11): Summary report. Influences on children's attainment and progress in Key Stage 2: Cognitive outcomes in Year 5 (Research Report No. RR828). Nottingham: DfES Publications.

- Sanson, A., Nicholson, J., Ungerer, J., Zubrick, S., Wilson, K., Ainley, J. et al. (2002). Introducing the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Canberra: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Sayers, M., Coutts, M., Goldfeld, S., Oberklaid, F., Brinkman, S. A., & Silburn, S. R. (2007). Building better communities for children: Community implementation and evaluation of the Australian Early Development Index. Early Education & Development, 18(3), 519-534.

- Sayers, M., Mithen, J., Knight, K., Camm, S., & Goldfeld, S. (2011). The AEDI in Schools Study: Final report: Report prepared for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations by the Centre for Community Child Health, The Royal Children's Hospital, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute. Melbourne: RCH & Murdoch Childrens Research Institute.

- Sayers, M., Moore, T., Brinkman, S., & Goldfeld, S. (2012). The impact of preschool on children's developmental outcomes and transition to school in Australia. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Seefeldt, C., & Wasik, B. A. (2006). Early education: Three-, four-, and five-year-olds go to school. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill-Prentice Hall.

- Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Woodhead, M. (2009). Effective early childhood programmes: Early childhood in Focus Four. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University with the Bernard van Leer Foundation.

- SuccessWorks. (2010). Evaluation of Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative. Final report. Melbourne: SuccessWorks.

- Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2004). The Effective Provision of Pre-School Education (EPPE) project: Final report. London, UK: Institute of Education, University of London.

- Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2010). Early childhood matters: Evidence from the Effective Pre-school and Primary Education Project. London, UK: Routledge.

- West, S., & Nolan, A. (2012). Outcomes and Indicators of a Positive Start to School: Development of Framework and Tools. Report prepared for the Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Melbourne. Melbourne: DEECD.

Sayers, M., West, S., Lorains, J., Laidlaw, B., Moore, T. G., & Robinson, R. (2012). Starting school: A pivotal life transition for children and their families. Family Matters, 90, 45-56.