Good practices with culturally diverse families in family dispute resolution

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

July 2013

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Dispute resolution practitioners should be aware of how culture is embedded in mediation processes and of the cultural values and communication patterns they and the parties bring to the process. This awareness will help them to engage in respectful dialogue about cultural contexts, respond ethically to the cultural power dynamics present in the mediation, and support the control that parties have over the mediation. This article presents findings from research on good practices in enhancing access for and engaging with clients from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds in the family dispute resolution (FDR) process. Surveys and interviews with practitioners were conducted nationally and locally in the Western Sydney region on good practice and organisational cultural competence and how these might be enhanced.

The development of the field of family dispute resolution (FDR) in Australia since 2008 has invited reflection about the practice of family mediation. Are FDR services accessible to all Australians, particularly those who may be vulnerable or disadvantaged? Is FDR practice sufficiently responsive to difference? How might FDR practitioners be supported to ensure their practice is culturally competent?

Two community-based organisations that manage Family Relationship Centres (FRCs)1 in western Sydney - with populations characterised by high levels of cultural, linguistic, ethnic and religious diversity, as well as socio-economic disadvantage - sought to answer these questions by initiating research in partnership with the University of Western Sydney.2 The research aimed to identify good practices in enhancing access for and engaging with clients from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds3 in the FDR process. It also aimed to identify appropriate ways to support and sustain culturally responsive practices in FDR. This paper summarises the findings of the two reports of this research (see Armstrong, 2010a, 2012) to provide guidance about enhancing the responsiveness and effectiveness of services for people from CALD communities, and to identify ways in which to support culturally responsive FDR practice.

Context

FDR and professional practice

Family dispute resolution is a form of family mediation that aims to help separated parents manage and resolve disagreements about their children's care. Since the 2006 family law reforms, FDR has become the gateway to the family law system for many such parents. Except where there are allegations or risks of violence or child abuse, or the matter is urgent, disputing parents must attempt FDR before they can file court applications (Family Law Act 1975, s 60I). The Federal Government funds community-based organisations to provide direct, telephone or online FDR through their own services or through the FRCs they manage. More than 100,000 people used these services in 2010, with about half using FRCs (Attorney-General's Department, 2011). Legal Aid Commissions, courts and private practitioners also offer FDR services. The rapid growth of FDR since 2006 has created a significant need for continuing professional and organisational development to enrich and monitor practice.

One area of FDR practice identified as needing support is in assisting FDR professionals to provide culturally competent service. In 2009, FRC professionals rated themselves as being not very confident in working well with families from CALD backgrounds (Kaspiew et al., 2009). A review of FDR practice in Legal Aid Commissions recommended that culturally and religiously appropriate models of FDR be developed and that culturally and religiously competent professional development be provided for FDR practitioners, managers, lawyers and intake personnel (KPMG, 2008). Other recent reports have recommended that the Australian Government support culturally responsive FDR and develop a cultural competency framework for the family law system, including in professional development (Australian Law Reform Commission & New South Wales Law Reform Commission, 2010; Family Law Council, 2012).

Access to FDR

The particular needs of vulnerable and disadvantaged children and families, including those from CALD and refugee backgrounds, are recognised by policies to promote accessibility, responsiveness and outcomes for clients using services, including FDR, within the Commonwealth Family Support Program (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs [FaHCSIA], 2011a, 2011b). Despite policies promoting access and inclusion, families from CALD backgrounds are generally under-represented in FDR services (Armstrong, 2010b). The Family Support Program data collection system shows that between 2006 and 2009 only 8% of FDR clients were born in a country where English is not the dominant language, even though they then comprised 14% of the Australian population (Armstrong, 2010b; Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2007). A change in the Family Support Program data collection method in 2010, which now identifies CALD clients on the basis of whether they speak a non-English language at home, suggests an even lower CALD participation rate in FRCs (3% in 2011-12) (FaHCSIA, 2012).

While there are pockets of good practice at variance with this trend (Ojelabi, Fisher, Cleak, Vernon, & Balvin, 2011), it appears that people from CALD backgrounds - particularly those with other markers of vulnerability and disadvantage, such as recently arrived migrants, women and refugees - use family law and FDR services less often than do others in the community (Family Law Council, 2012; Women's Legal Services NSW, 2007). This is despite a significant documented need for relationship and family law services for families from CALD and refugee backgrounds (Dimopoulos, 2010; Fraser, 2009; Reiner, 2010; Stoyles, 1995).

In general, cultural communities consulted about their family law needs have expressed interest in using mainstream non-adversarial methods of resolving disputes, including family mediation and dispute resolution (Family Law Council, 2012; Legal Services Commission of South Australia, 2004). Research and consultations with people from CALD communities indicate that they understand some of the benefits of mainstream family mediation and would be willing to use it if they were confident that service providers were culturally competent and if their communities were educated about the process (Family Law Council, 2012; Pankaj, 2000). There is little research about what works to engage CALD families in family law services, particularly family mediation. Successful strategies are generally premised on community development principles of working with community gatekeepers and multicultural or culturally specific services to understand the cultural needs and diversity of needs, and building partnerships that develop appropriate responses (Butt, 2006; Dimopolous, 2010; Family Court of Australia, 2008; Family Law Council, 2012; Sawrikar & Katz, 2008). Such strategies require sustained leadership, resources and policy commitment, in particular to develop a workforce that is culturally representative, culturally aware, culturally sensitive and culturally competent (Armstrong 2010b; Butt, 2006; Family Law Council, 2012; Sawrikar & Katz, 2008).

Culturally competent FDR

Cultural competence is the organisational and professional capacity to provide effective and appropriate service delivery to individuals from non-dominant cultural groups (Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Isaccs, 1989). Culturally competent workers "build on and subsume" cultural awareness (knowledge of cultural norms) (Sawrikar & Katz, 2008, p. 14) and cultural sensitivity (recognition of diversity within cultural groups) to develop an appreciation of their own cultural norms and of the dynamism, complexity and significance of culture in shaping individual and community identity and the processes of meaning-making (Education Centre Against Violence, 2006). They approach working with clients from minority cultural backgrounds from a perspective of "informed not-knowing", which places the client as the expert in their relationship with their culture (Laird, 1998, cited in Furlong & Wight, 2011, p. 39). They demonstrate "cultural humility" rather than competence, as they engage in reflective self-critique, recognise white privilege, check power imbalances and identify needs through client-focused and respectful service (McPhatter & Ganaway, 2003; Mederos & Woldeguiorguis, 2003; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998; Walter, Taylor, & Habibis, 2011).

Culture plays an important role in conflict and conflict management, including in mediation. Culture influences perceptions of selfhood and relational connections, attitudes to conflict and approaches to resolving it, and "how identities and meanings play out" in negotiating the issues (Le Baron & Pillay, 2006, p. 16; see also Avruch, 1998; Brigg, 2003). Dispute resolution practitioners should be aware of how culture is embedded in mediation processes and of the cultural values and communication patterns they and the parties bring to the process, and understand when and how people use culture and cultural tools in mediation. This awareness will help them to engage in respectful dialogue about cultural contexts, respond ethically to the cultural power dynamics present in the mediation, and support the control that parties have over the mediation (Astor, 2007; Brigg, 2009; Doerr, 2012). It will also help FDR practitioners fulfil their ethical and legal obligations to support children's right to enjoy their culture (Armstrong, 2011; Family Law Act, s 60C).

Design of the study

The first stage of the research described here aimed to understand how FRCs might enhance access to FDR for families from culturally diverse backgrounds, and to identify good FDR practices that are responsive to culture. The main data gathering method used was an open-ended interview, as this kind of inquiry is particularly powerful for understanding and evaluating the how and why of processes (Patton, 2001). The research participants were professionals providing services directly to CALD and minority faith communities, and professionals working in FDR services. More than 200 invitations were mailed to prospective participants. Twenty-two FDR practitioners and two FRC personnel from 16 FRCs and organisations providing FDR in urban and regional cities across the country, and 20 professionals from 11 organisations assisting families from culturally diverse backgrounds in western Sydney agreed to participate in an interview. Inductive thematic analysis was adopted to analyse the interview data (Brown & Clarke, 2006). Meaningful extracts of data were coded using a data management software program, and subsequently collated into common narrative themes. These themes were conceptually refined following critical review. The themes inform the substance of the stage one research findings.

The second stage of research sought to build on the stage one findings by identifying the perceptions of a wide range of FDR professionals about their own and their organisation's cultural competence, and to identify their views about what might enhance this. This inquiry was conducted using a mixed-methods approach that combined an online survey with a semi-structured interview. Invitations to participate in the research were emailed to 324 individual FDR practitioners and 178 institutional FDR providers. The SurveyMonkey online survey was completed by 219 respondents.4 The survey data were tabulated and analysed using descriptive statistics for demographic and professional characteristics. Frequencies (number and percentage) of the rating of all other questions were reported. Differences in survey response by work role, length of time in role and service type were explored using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc comparisons were made using Bonferroni, Tamhane or Tukey tests. The post hoc test was chosen on the basis of results of Levene's Test for Equality of Variances. FDR practitioners comprised 70% of survey respondents, with intake personnel, administrative officers and child consultants comprising the rest. Slightly more than half worked in FRCs, and 17% from Legal Aid Commissions. Non-government community-based FDR providers comprised 15%, while 10% were private FDR providers. In addition, 24 survey participants responded to an invitation to participate in a half-hour telephone interview to explore participants' experiences of "real learning" about culture. Inductive thematic analysis was also used to analyse the stage two interview data, as described above.

What can FDR providers do to enhance access for CALD families?

The stage one research findings indicate that the most effective way to enhance access to FDR is for FDR providers to establish relationships with the gatekeepers of CALD and minority faith communities. Such relationships assist FDR providers to identify the service needs of the specific CALD communities in their catchment area and to understand the barriers to using FDR that might exist. Initiatives to establish relationships also provide community leaders with the opportunity to assess the organisation's commitment to working with diverse communities, and to develop trust in the organisation's capacity to assist clients in a culturally respectful manner. Relationships also create a platform for developing mutual referral pathways, working in partnership, and fostering community capacity for appropriate service choice.

Fostering relationships

The starting point for initiating relationships is to speak with a wide range of organisations to:

find out what the issues are and don't assume anything about that community … You've got to find out … who the community is and focus … on getting to know the community. (Lawyer, minority faith-based women's service)

It is important to connect with the leadership and workers in community-based and ethno-specific organisations, which are often gatekeepers to CALD communities. But as one observed:

that's not enough … You're going to have to go where the people are going, to the mosque and churches, to resolve family disputes. (Manager, culturally specific service)

Many stressed the importance of developing:

links with our religious leaders … Religious leaders play such an important role at times of family disputes, even for people who have a very low level of religiosity. (Lawyer, minority faith-based women's service)

This view was not universal however, and one respondent cautioned that in her experience religious leaders have "a very strong bias towards men and not breaking up families" (Manager, children's service). Identifying and meeting with community and religious leaders may be complex and require assistance from agencies working with CALD families.

Some referred to misunderstandings that might discourage the use of FDR by both women and men. Women "have no idea what's their rights here, what's the law here" and men may perceive:

that the Family Relationship Centre is a place to give the woman more than her rights and they will be something unfair to [the men] … because divorce happens easier here. (Family support worker, culturally specific service)

In some cultural and faith communities it is unlikely that people contemplating divorce would attend an FRC "because that's duplicating already what is happening" in the mosque (Manager, minority faith-based service) or "through elders and family members rather than using something like an FRC" (Manager, FRC).

Others speculated that people were uncertain whether the FDR organisation will "really understand where I've come from" (Family support worker, multicultural service). Unless people were confident that organisations were sensitive to the cultural and religious dynamics of separation, they would question:

why would I go [when] … I'm pretty vulnerable? Why would I walk into a service that might judge me on how I live my life? (Lawyer, minority faith-based women's service)

The kind of engagement required to foster relationships and:

build trust … requires time ... It's evolving, and it spreads in a network way. It's not about what you know, it's about who you know. (FDR practitioner, FRC)

Working in partnership

A key theme in the stage one interviews was the importance of working in partnership with communities, and with the services that work closely with them. As one respondent observed:

If FRCs are serious about expanding their services to the whole community, the only way that they can do that is in collaboration with organisations that work specifically with those communities … We know how to work with the community. (Counsellor, ethno-specific service)

Another cautioned that:

commitment to being culturally responsive has to be financially viable, because those [community] agencies are usually very small agencies. (FDR practitioner, minority faith-based service)

Working in partnership required that mainstream organisations:

think how they can support these [community] services as well … How can they integrate the services that they provide? … Can they operate outreach programmes? (Manager, minority faith-based service)

One area of need identified by a number of respondents was "education for their communities" about the law and legal system, and about FRCs and family law in particular (Manager, FRC). However, other cultural communities:

didn't want information about family law systems … The real key thing for them was the stuff … that will support [their] parenting. (Manager, FRC)

As another participant observed:

it's really about engaging with the community that you're providing the services for … Listening and seeking advice: "Well you know, we're thinking of doing this, what should we do?" (Manager, minority faith-based service)

Working in partnership enhances mutual understanding and increases community capacity to navigate mainstream processes and, ultimately, make more informed service choices. It requires time, but also genuine commitment to the goal of facilitating access by CALD families, equality and the mutuality of partnerships, and the resources and capacity to sustain relationships.

Establishing structures that facilitate access

The need for structures to facilitate access was a recurring theme in the stage one interviews. The capacity to sustain relationships, and to develop trust in a mainstream organisation, may effectively be invested in "a community development person or community liaison person" (Manager, culturally specific service). Individuals are important, as:

people need to build connections with each other as human beings … People relate to that person, and they will come back. (Manager, culturally specific service).

Several respondents remarked on the value of employing bicultural and bilingual staff, but there were divergent views. They "bring an enormous amount of knowledge and experience" about communities (Cultural liaison officer, FRC). Some clients might:

prefer to find someone from the same culture, [because] that's easy to build rapport and trust (Family support worker, multicultural service)

but, equally, others may:

feel ashamed to talk about their issues in front of someone from the same culture, so they prefer someone else. (Family support worker, culturally specific service)

Employing bicultural staff can also lead to a perception that the organisation is culturally competent when this may not be the case. As one explained, it may be risky if:

bicultural workers buy into their cultural belief system, and haven't explored and dissected that for themselves. (Manager, children's service)

Establishing mechanisms for accessing a range of community views is important, and has been achieved by some FDR organisations through a cultural consultative committee of professionals and community leaders. Others cautioned that the time invested by community groups in formal consultative structures was considerable and that such a committee should:

be very clear about what it needed from … the members they've invited around the room … [and that you] follow through with what we've given, what we've offered. (Manager, culturally specific service)

Culturally responsive FDR

Stage one of the research also sought to identify culturally responsive FDR practices. The data indicate that culturally responsive FDR professionals appreciate the relevance of cultural contexts to mediating post-separation disputes and the potential importance of these contexts to the families in dispute. They have developed the capacity to sensitively explore culture with each individual and family, and the ability to respond appropriately to this in the FDR process. They recognise that cultural responsiveness in FDR will be limited by the law, FRC processes and resources, and the preferences, needs and capacities of the parties.

Appreciating the value of and limits to accommodating culture in FDR

Themes from the stage one interviews indicated that FDRP awareness of the relevance of culture was critical to many clients' capacity to effectively participate in FDR. As one noted:

we can only understand what our clients are going through and what the children are going through if we have an increased sensitivity to the cultural parameters within which they create meaning out of their family and their society. (Manager, FRC)

Another FDRP acknowledged the challenges of trying to understand a client's cultural world, saying:

it's very important … to be educated and to find out more, but some of these matters are so diverse and complex, it's almost impossible. (FDR practitioner, FRC).

There was agreement that:

it's very hard for people to separate [culture and religion] and to distinguish the two … I find it difficult myself sometimes. (FDR practitioner, FRC)

One practitioner referred to the:

complexities of managing the gender stuff, [because it] was extremely difficult to know what's appropriate and what's not … You don't know whether you're bringing in your own cultural assumptions about what men and women should and shouldn't do. (FDR practitioner, FRC)

For this reason, it was important for practitioners to reflect on the influence of their own cultural contexts. Some positioned themselves as translators of the dominant culture to assist clients to better navigate it, and saw their role as:

explaining the dominant culture … that is sitting there in the room. That's the bridge, and then we can work with everybody. (Manager, children's service)

An appreciation of the significance of culture also meant practitioners were aware of the limits of cultural responsiveness and avoided feeling paralysed by their perceived obligations to "acknowledge culture and be culturally aware all the time" (Manager, children's service). One FDR practitioner referred to her experience of using law to challenge what may be considered "cultural" by giving:

a very clear understanding of what's acceptable … within our Family Law Act … and in fact what he sees as OK is for us violence. My risk is that he loses faith or trust in me being impartial. (FDR practitioner, FRC)

The interview responses suggest that it is not the level of cultural knowledge that distinguishes the responsive mediator, but an appreciation of cultural complexity, an awareness of the influence of their own cultural frameworks, an attitude of humility, and a disposition for sensitive inquiry.

Exploring the relevance of culture with each family

The disposition for sensitive inquiry is evident in an approach which places the family as:

the experts of their culture and … the expert of their stories and their experience. (FDR practitioner, FRC).

This requires practitioners to:

approach each family with an open mind … Rather, be informed by what they tell you, how they are operating, what's important to them, because often it's about how they interpret their culture and religion. (Lawyer, minority faith-based service; emphasis in original)

It also means that practitioners must adopt a perspective of "informed not-knowing" (Laird, 1998, cited in Furlong & Wight, 2011). One participant highlighted the need to probe more deeply:

particularly when I have a sense of thinking that things don't make sense … So that's when I need to be a little bit more curious, and respectfully curious, with clients in terms of working out just where they are coming from. (FDR practitioner, FRC).

Responding appropriately to cultural contexts in the FDR process

The stage one interview responses demonstrate that culturally responsive practitioners and services develop a repertoire of responses that are respectful of cultural difference and are framed by the legal and practice contexts in which FDR occurs. They engage in dialogue with clients to understand their preferences, which may be simply asking what they need, "giving them options … giving them that choice" (Counsellor, multicultural service). This may involve assisting a client:

who is struggling with the idea of a woman having some kind of control around what's happening to him [to participate more effectively in FDR by seating him] opposite the male FDRP and I would be opposite the female so that I can be attentive to her first and foremost, but also be able to be respectful of him in the way that he understands within his culture. (FDR practitioner, FRC)

Culturally responsive practice may involve helping parents to understand what is in the child's best interests when they say: "Well, I want the child because, according to our tradition, the child should be with the father" or "the child should be with the mother" (FDR practitioner, minority faith-base FDR service). It may involve advocating for children to promote their right to see their grandparents and extended family, "and impress upon [parents] the children have a right to see them as well" (FDR practitioner, FRC).

Many respondents stressed the importance of considering the role of the extended family in post-separation care, or their possible reaction to the agreements that parents reach. Some were developing an "extended family model of FDR … [where] it's a benefit to the outcomes for the child" (Manager, FRC). Others were exploring how:

people from the communities [or support personnel] can support a family through the mediation process and … assist the family to use mediation and get the best from it. (FDR practitioner, FRC)

They also observed that such approaches were likely to require more resources because "you've got to go a little gentler and a little slower and work at it a little differently" (FDR practitioner, FRC). Making culture visible, exploring its relevance and responding to it appropriately can promote party self-determination in the dispute resolution process, and also support the interests of vulnerable third parties, like children, including their right to enjoy their culture.

Supporting culturally responsive FDR

The survey and interviews responses in the second stage of this research identified a significant commitment among FDR professionals to culturally responsive practice, a high level of self-reported cultural responsiveness by FDR professionals, and a strong desire to be supported in this with a range of resources and professional development strategies.

Professional cultural competence

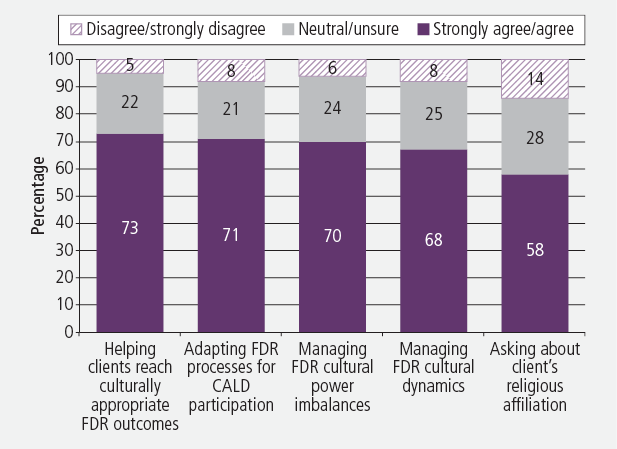

Almost all participants from the online survey agreed it was important to provide culturally responsive FDR, and three in four agreed they felt culturally responsive in their FDR work. A large majority (85+%) agreed or strongly agreed that they had confidence in maintaining impartiality when working with CALD clients; inquiring about clients' cultural backgrounds; identifying a client's need for an interpreter; communicating with clients from CALD backgrounds; helping clients consider their children's right to enjoy their culture; identifying cultural influences in the FDR process, including their own; assisting clients whose religious affiliation differed to their own; and identifying the presence of violence in families from CALD backgrounds. Figure 1 reveals that a lower proportion of FDR professionals agreed or strongly agreed that they had confidence in:

- helping clients reach FDR outcomes that are culturally appropriate (73%);

- adapting FDR processes to facilitate participation by CALD clients (71%);

- managing cultural power imbalances (70%);

- responding to the cultural dynamics of FDR processes (68%); and

- asking about a client's religious affiliation (58%), although only a third of participants agreed their services regularly did this.

Figure 1: Agreement by FDR professionals that they had confidence in providing culturally responsive FDR in specific areas

Statistically significant differences were identified between groups of professionals' feelings of cultural competence. Less experienced and Legal Aid FDR professionals were less confident responding to cultural contexts in FDR. Administrative officers working in FDR services were less likely than all other respondents to agree that they felt culturally responsive, that it was important to be culturally responsive and that they would like to further develop this capacity in their FDR work.

Organisational cultural competence

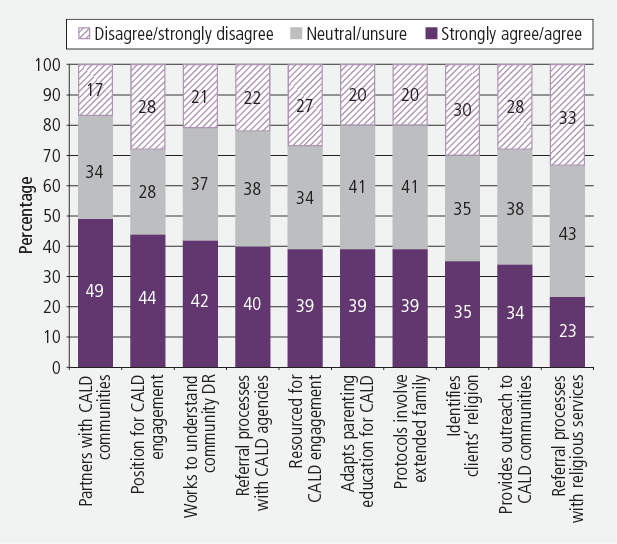

While most participants in the online survey said that they felt culturally responsive, fewer believed the organisation in which they worked was culturally responsive. Participants agreed or strongly agreed that their organisations were succeeding in: identifying clients' cultural background at intake or assessment (87%); encouraging professional development to foster cultural competence (86%); providing cultural awareness training (80%); adopting best practice with interpreters (77%); and considering cultural issues in debriefing and supervision practices (77%).

However, Figure 2 reveals that only half agreed or strongly agreed that their organisation actively engaged local CALD communities or worked with CALD service providers to support CALD families. And a lower proportion of participants agreed or strongly agreed that their organisations were culturally responsive in the following domains:

- working in partnership with CALD communities (49%);

- having a dedicated position to promote engagement with CALD communities (44%);

- working with CALD communities to understand community-based dispute resolution (42%);

- developing mutual referral processes with CALD services and communities (40%);

- being adequately resourced to engage with CALD communities (39%);

- adapting parenting education programs commonly held prior to FDR (39%);

- developing protocols to respond to the needs of CALD clients and involve the extended family in the FDR process (39%);

- identifying the religious background of clients (35%);

- providing outreach to CALD communities (34%); and

- developing mutual referral processes with religious leaders or services (23%).

Figure 2: Agreement by FDR professionals that their organisation provided culturally responsive services in specific areas

Statistically significant differences were identified in the responses of Legal Aid FDR professionals. They were less likely to agree than other FDR professionals that their organisation was adequately resourced to engage with communities from CALD backgrounds, or that Legal Aid Commissions had developed referral processes with CALD communities or with minority faith communities.

What would support FDR professionals to be culturally responsive?

Although most survey participants said that they felt culturally competent, most (88%) also wished to further develop this capacity. They agreed that professional development activities, as well as a range of human, information and financial resources, would support them to develop and sustain culturally responsive practice and service. Cultural awareness training and external professional development activities were rated as being the most useful ways in which to support cultural responsiveness (both 92%), and other helpful factors included:

- being provided with examples of good practice of working with CALD communities (91%);

- undertaking professional development activities specifically designed for their practice (89%);

- having access to information about local cultural organisations, cultural facilitators and cultural resources (88%);

- having adequate funding for community engagement (87%);

- appointing staff and FDR practitioners from culturally diverse backgrounds (83%); and

- having more emphasis on cultural issues in vocational FDR training (80%).

Survey participants indicated that their preferred professional development activities were forms of collaborative, engaged and experiential learning. Most support was expressed for having conversations with CALD community members and agencies about their issues (93%), and participating in collaborative reflective practice and discussion with FDR colleagues about culture and FDR (90%). Almost all survey participants agreed that developing the following abilities would support their practice and service provision:

- adapting FDR processes to facilitate the participation of CALD clients (93%);

- developing cultural self-awareness (95%);

- supporting children's rights to enjoy their culture (96%);

- assisting CALD families experiencing domestic violence (96%);

- managing cultural dynamics in FDR (97%);

- working with interpreters (98%);

- facilitating children's best interests in cross-cultural contexts (99%); and

- recognising different communication styles (99%).

More than 90% of participants agreed that better understanding of the following matters would support culturally responsive FDR:

- community-based dispute resolution (94%);

- how to engage CALD communities effectively (95%);

- cultural and religious norms about parenting, separation and family (98%);

- the role of culture in dispute resolution (98%); and

- cultural influences on child development (99%).

The preference for collaborative, reflective and conversational learning modes was reinforced in the stage two interviews. Participants were asked about their moments of "real learning" about culture and how this kind of learning might be facilitated in FDR professional contexts. Many spoke of the need to avoid a "compartmentalised, stereotyped approach" to understanding culture in FDR, and questioned the "superficial" and "cynical" approaches to culture evident in some cultural awareness training.5 They voiced a preference for something that was "more tailored to my particular practice" and which allowed them "to drill down a little bit more" to analyse the complexities of culture in FDR. Many of the moments of real learning about culture concerned failures of dialogue, of making unwarranted assumptions or not inquiring effectively. One queried her failure to ask:

that question in the right way, to find out that, no, there is no way she wanted to be in the same room as him … How could I have missed that?

To remedy such omissions, interviewees suggested engaging in authentic and mindful dialogue with parties. Such dialogue required that professionals reach out to find common ground, to "develop compassion", to interact "from an authentic base, a sense of humility". Practitioners should approach every session:

as an intercultural session … where different cultures meet, and probably just be tentative and curious about how people use culture, much more than what it is. (emphasis in original)

Interviewees suggested that it was essential for professionals to have conversations with themselves about culture, "to focus your attention on the questions that you constantly have to ask yourself". These conversations with self required practitioners to be aware of their own influences on the client and the process, and to be "really, really, really present in the situation".

Interview participants also highlighted that their preferred learning context was the conversations that they had with colleagues - whether informally, or more formally in debriefing, supervision and peer supervision meetings, and with the wider FDR or mediation community. As one explained, conversation with colleagues:

sharpens what you think, what you do, and focuses your attention again to the questions that you constantly have to ask yourself.

The themes of dialogue and of collaboration were also evident in interviewees' awareness that genuine and mutual engagement with cultural communities, despite its many challenges, was the most potent source of learning for communities and for FDR providers. One remarked that to deepen her understanding of culture in FDR, she "would appreciate actually hearing the stories from people within those communities". Several expressed the view that the most effective way to learn about cultural communities, and for people in communities to appreciate FDR, was to be involved in "community education and development, like the outreach component, to go out to those communities" (Project Manager, FRC). This needed to be done with care and consultation, to avoid raising unrealistic expectations, and to ensure there was the capacity to sustain the connection.

Discussion and implications

Supporting FDR services to engage with CALD communities

The research findings suggest that the most effective way to enhance access to FDR by families from CALD backgrounds is to foster relationships and develop partnerships with CALD community leaders and with agencies working directly with communities. Research participants indicated that "conversations with CALD community members and agencies about their issues" in a manner that encouraged mutual listening and dialogue was most likely to support culturally responsive practices. Many agreed that the appointment of cultural liaison personnel would facilitate CALD community engagement and ultimately enhance access, but that few organisations did this. There was also strong endorsement of the provision of resources showcasing good practices with CALD communities, and for guidance about effective engagement. FDR professionals were not confident that their organisations engaged well with CALD communities, developed community partnerships, or were adequately resourced to do either. Nor did they believe their organisations had developed mutual referral processes with cultural or minority faith communities.

Engaging CALD communities should not overtax service providers or communities, or create unrealisable expectations (Urbis Keys Young, 2004). Good practice for mainstream services engaging with CALD communities, particularly in the challenging area of family breakdown, emphasises principles of reciprocity, equality and trust (Family Court of Australia, 2008; Legal Services Commission of South Australia, 2006). To facilitate better outcomes, the purposes, complexities and challenges of community engagement and of appropriately supporting these families at and following separation needs to be better understood, adequately resourced and properly guided. This is particularly important in light of the collaborative stakeholder relationships that the Vulnerable and Disadvantaged Client Access Strategy now requires of most Family Support Program services, including FRCs (FaHCSIA, 2011a). It is also necessary to appreciate that "the process of successfully engaging communities is an outcome in its own right" (Family Court of Australia, 2008, p. 43), and that effective, sustainable engagement is resource-intensive and requires high levels of organisational cooperation, commitment and capacity.

Supporting people from CALD backgrounds to participate in FDR

A number of strategies were suggested to support the participation of CALD clients in FDR. Acknowledging the importance of culture and religion during family separation for many from CALD backgrounds, and providing the opportunity to engage in respectful dialogue about these matters may support party control in the FDR process. Such discussions may also provide guidance about what, if any, adjustments might be made to enhance participation, as FDR professionals said they did not feel confident in this area. The survey results indicate that few organisations adapted their parenting education programs to facilitate the participation of CALD parents. The role of such programs in encouraging parents to focus on their children's post-separation needs has been clearly established (McIntosh & Deacon-Wood, 2003). It would follow that such programs could be adapted to enhance CALD parental participation, and to promote better understanding of the interests and rights of children in this context.

Participants in the survey reported that few organisations routinely identified the religious background of clients, few felt confident asking about this, and the intersection between culture and religion seemed poorly understood. Religious leaders and organisations play an important role in supporting family relationships, assisting couples to resolve problems, and referring people to family relationship services (Kaspiew et al., 2009; Macfarlane, 2012). Given this, it would be useful to further explore how religion might be better understood in the context of family separation, and how appropriate channels of mutual communication and referral might be established. Other strategies identified by the research as being useful include developing protocols to respond to the needs of CALD clients, and to involve support people and the extended family in the FDR process, although the survey results suggest that few organisations do this. It would be valuable to identify and publicise good practice in these areas.

Supporting practitioners to provide culturally responsive FDR

Although professionals generally rated themselves as being culturally competent, they indicated the need for further support in sustaining this in their FDR practice. Responses by FDR professionals working in administrative capacities, who were newly appointed or working in Legal Aid Commissions, demonstrated particular need for support. Elements of good FDR practice with families from culturally diverse backgrounds included awareness of the role of and complexity of culture in post-separation family disputes (particularly professional self-awareness of the influence of their own cultural contexts), and the capacity to engage in sensitive dialogue about culture with clients and adjust their practice to facilitate participation by clients.

Participants expressed support for engaging in professional development, including cultural competence training, so long as this also provided opportunities to analyse the complexities of culture in FDR. They indicated that the most effective way to sustain responsiveness to culture in FDR was to participate in regular, structured, collective opportunities to critically reflect on the way in which culture manifests in FDR. Such activities could model "the kinds of questioning, collaborative and conversational techniques which can lead to a richer understanding of client and practitioner perspectives and the way culture shapes these" (Armstrong, 2011, p. 245; see also Bagshaw, 2008). This preference confirms the value of taking part in collaborative, reflective professional learning in family relationship services (Urbis Keys Young, 2004) and other professional fields, including mediation (Collin & Karsenti, 2011; Lang & Taylor, 2000; Reynolds, 2011).

FDR organisations are responsible for creating the opportunities to facilitate these kinds of professional conversations, possibly in existing debriefing and supervision practices. The process of "cultural auditing", developed to guide and structure reflective practice and facilitate dialogical thinking about culture in counselling, offers a very promising model that may be readily adapted to FDR (Collins, Arthur, & Wong-Wylie, 2010), as does the cultural competence case study approach developed by the NSW Education Centre Against Violence (2006).

Conclusion

Family dispute resolution is the default option for large numbers of separating couples in dispute about their parenting arrangements. It is important then that steps are taken to ensure that vulnerable populations, including families from CALD backgrounds, are supported to understand and participate effectively in FDR. Developing services and professional practices that are culturally competent can assist CALD families become aware of and exercise greater control in FDR processes. The responsibility for developing and sustaining culturally competent FDR rests jointly with the professionals, organisations and funding bodies that provide these services.

Endnotes

1 From 2006, 65 FRCs were established across Australia to provide a "single shop front single entry point into the broader family law system" (Australian Government, 2005, p. 11). FRCs are funded by the Federal Government, but run by a variety of non-government organisations selected by competitive tender. The core business of most FRCs is now FDR.

2 CatholicCare Sydney and Anglicare Sydney were the lead partners in the consortium, which successfully tendered for the FRCs in the Sydney suburbs of Bankstown and Parramatta respectively.

3 The acronym CALD is used as shorthand to refer to minority ethnic communities, including new, emerging and refugee communities, despite the significant differences within and between such groupings and the problematic nature of the term (Sawrikar & Katz, 2009).

4 It is difficult to accurately calculate the response rate as institutional providers may employ a few or many FDR professionals.

5 All quoted comments from the stage two interviews are by FDR practitioners, unless otherwise indicated.

References

- Armstrong, S. (2010a). Culturally responsive family dispute resolution in Family Relationship Centres: Access and practice. Sydney: CatholicCare and Anglicare.

- Armstrong, S. (2010b). Enhancing access to family dispute resolution for families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (AFRC Briefing No. 18). Melbourne: Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse.

- Armstrong, S. (2011). Encouraging conversations about culture: Supporting culturally responsive family dispute resolution. Journal of Family Studies, 17(3), 233-248.

- Armstrong, S. (2012). Encouraging conversations about culture: Supporting culturally responsive family dispute resolution. Sydney: Anglicare and CatholicCare.

- Astor, H. (2007). Mediator neutrality: Making sense of theory and practice. Social and Legal Studies, 16, 221-230.

- Attorney-General's Department. (2011). Annual report 2010-2011, Canberra: AGD.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). Migrants: 2006 Census of Population and Housing, Australia (Cat. No. 34150DS0018). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Government. (2005). A new family law system: Government response to Every Picture Tells a Story. Response to the report of the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs Inquiry into Child-Custody Arrangements in the Event of Family Separation. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Law Reform Commission and NSW Law Reform Commission. (2010). Family violence: A national legal response. Final report. Sydney: ALRC.

- Avruch, K. (1998). Culture and conflict resolution. Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace Press.

- Bagshaw, D., (2008). Mediation, culture and transformative peacemaking: Constraints and challenges. Keynote address presented at the 4th Asia Pacific Mediation Forum Conference, Mediation in the Asia Pacific: Constraints and Challenges, International Islamic University, Malaysia.

- Brigg, M. (2003). Mediation, power, and cultural difference. Conflict Resolution Journal, 20, 287-306.

- Brigg, M. (2009). The new politics of conflict resolution: Responding to difference. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

- Butt, J. (2006). Are we there yet? Identifying the characteristics of social care organisations that successfully promote diversity (Race Equality Discussion Paper 01). London: Social Care Institute for Excellence.

- Collin, S., & Karsenti, T. (2011). The collective dimension of reflective practice: The how and why. Reflective Practice, 12(4), 569-558.

- Collins, S., Arthur, N., & Wong-Wylie, G. (2010). Enhancing reflective practice in multicultural counseling through cultural auditing. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88, 340-347.

- Cross, T., Bazron, B., Dennis, K., & Isaccs, M. (1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care: A monograph for effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Centre.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2011a). Family Support Program access strategy requirements: Vulnerable & Disadvantaged Client Access Strategy. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2011b). Operational framework for Family Relationship Centres. Canberra: FaHCSIA. Retrieved from <www.fahcsia.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/frcs_operational_framework.pdf>.

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2012). FDR FRC client profile report 1/7/11-30/6/12. Canberra: FSP Operational Branch, FaHCSIA.

- Dimopoulos, M. (2010). Implementing legal empowerment strategies to prevent domestic violence in new and emerging communities (Issues Paper No. 20). Sydney: Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse.

- Doerr, A. (2012, 11-13 September). Exploring culture: The relevance of culture in mediation and the role of mediation in a multicultural society. Paper presented at 11th National Mediation Conference, Sydney.

- Education Centre Against Violence. (2006). Cultural competence in working with suicidality and interpersonal trauma. Sydney: ECAV.

- Family Court of Australia. (2008). Families and the law in Australia: The Family Court working together with new and emerging communities. Canberra: Family Court of Australia.

- Family Law Council. (2012). Improving the family law system for clients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Canberra: Family Law Council.

- Fraser, K. (2009). Out of Africa and into court: The legal problems of African refugees. Melbourne: Footscray Community Legal Centre.

- Furlong, M., & Wight, J. (2011). Promoting "critical awareness" and critiquing "cultural competence": Towards disrupting received professional knowledges. Australian Social Work, 64(1), 38-54.

- Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., Qu, L., & the Family Law Evaluation Team. (2009). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- KPMG. (2008). Attorney-General's Department: Family dispute resolution services in legal aid commissions: Evaluation report. Sydney: Legal Aid New South Wales.

- Lang, M., & Taylor, A. (2000). The making of a mediator: Developing artistry in practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- LeBaron, M., & Pillay, V. (2006). Conflict, culture and images of change. In M. LeBaron & V. Pillay (Eds.), Conflict across cultures. Boston, MD: Intercultural Press.

- Legal Services Commission of South Australia. (2004). Report on the African communities consultation for the Family Law and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Communities Project. Adelaide: Legal Services Commission of South Australia.

- Legal Services Commission of South Australia. (2006). Family Law and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities Project: Legal education kit. Adelaide: Legal Services Commission of South Australia.

- Macfarlane, J. (2012). Islamic divorce in North America: A shari'a path in a secular society. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- McIntosh, J., & Deacon-Wood, H. (2003). Group interventions for separated parents in entrenched conflict: An exploration of evidence based frameworks. Journal of Family Studies, 9(2), 187-199.

- McPhatter, A., & Ganaway, T. (2003). Beyond the rhetoric: Strategies for implementing culturally effective practice with children, families, and communities. Child Welfare, 82(2), 103-124.

- Mederos, F., & Woldeguiorguis, I. (2003). Beyond cultural competence: What child protection managers need to know and do. Child Welfare, 82(2), 125-142.

- Ojelabi, L. A., Fisher, T., Cleak, H., Vernon, A., & Balvin, N. (2011). A cultural assessment of family dispute resolution: Findings about access, retention and outcomes from the evaluation of a Family Relationship Centre. Journal of Family Studies, 17(3), 220-232.

- Pankaj, V. (2000). Family mediation services for minority ethnic families in Scotland. Glasgow: The Scottish Executive Central Research.

- Patton, M. (2001). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Reiner, A. W. (2010). Background paper for African Australians: A review of human rights and social inclusion issues. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Reynolds, M. (2011). Reflective practice: Origins and interpretations. Action learning. Research and Practice, 8(1), 5-13.

- Sawrikar, P., & Katz, I. (2008). Enhancing family and relationship service accessibility and delivery to culturally and linguistically diverse families in Australia. Melbourne: Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse.

- Sawrikar, P., & Katz, I. (2009, 8-10 July). How useful is the term "culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD)" in the Australian social policy discourse? Paper presented at the Australian Social Policy Conference, An Inclusive Society? Practicalities and Possibilities, Sydney.

- Stoyles, M. (1995). Partners in any language: Managing diversity. Meeting the access and equity needs of consumers from non-English speaking background in Commonwealth funded marriage and relationship counselling services. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Tervalon, M., & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9, 117-125.

- Urbis Keys Young. (2004). Review of the Family Relationships Services Program: Prepared for Department of Family and Community Services and Attorney-General's Department. Canberra: Department of Family and Community Services.

- Walter, M., Taylor, S., & Habibis, D. (2011). How white is social work in Australia?' Australian Social Work, 64(1), 6-19

- Women's Legal Services NSW. (2007). A long way to equal: An update of A Quarter Way to Equal. A report on barriers to access to legal services for migrant women. Sydney: Women's Legal Services NSW.

Armstrong, S. (2013). Good practices with culturally diverse families in family dispute resolution. Family Matters, 92, 48-60.