Attitudes towards intergenerational support

Download Research report

Overview

This fact sheet examines the views of Australians about the obligations of parents and their adult children to provide financial and accommodation support to one another, and compares the views of respondents according to demographic characteristics.

Key messages

- The majority of respondents agreed that both parents and adult children should help the other if financial support is needed. However, fewer respondents (47%) agreed that adult children should let their ageing parents live with them.

- Men were slightly more likely to agree with providing intergenerational support than women.

- Respondents under 35 years were the most likely to agree that they should support their parents financially and with accommodation. As respondents got older, the numbers of those agreeing decreased.

- Within the adult children group, non-parents were more likely than parents to agree that adult children should provide their parents with accommodation or financial support.

- Respondents born in a non-English-speaking country were the most likely to agree with the idea of intergenerational support.

Background

Australia’s population is not only ageing but is already "more aged" than many countries in the world (United Nations, 2013). In 2016 the first of the baby boomers turned 70, and increasing numbers are entering or already in their late 60s—thereby joining the growing numbers of Australians deemed "older people" in demographic analyses (e.g., Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2012b; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2014).1

The steady increase in population ageing, which has been apparent for over four decades, largely results from increasing life expectancy in the context of a total fertility rate that was particularly high in 1946–66 and below replacement level since 1976 (ABS, 2012b).2

At 30 June 2014, 15% of Australians were aged 65 years and over (ABS, 2016a). Depending on the set of assumptions adopted, the ABS (2013b) projects that the proportion of the total population in this older age category will increase to 22–25% by 2061 and 25–27% by 2101. The proportion of those aged 85 years and older is projected to increase from 2% in 2014 to 4–6% in 2061 and 6–8% in 2101.3

Population ageing is a cause for celebration. As the Productivity Commission (2013) explained: "The primary ‘culprit’ is a virtuous one—Australians are experiencing lower mortality rates and enjoying longer lives" (p. 5). Furthermore, increasing life expectancy will typically entail a greater number of additional years of good health than of profound or severe disability (AIHW, 2014).

However some authors (e.g., Morris, 2013; van Onselen, 2014) have argued that the current level of ageing in western countries, including Australia, means that we are facing a "tsunami" or "time bomb" of social and economic challenges.

The consequences of an ageing population

An ageing population draws heavily on government budgets, given the high costs of pensions, health care and aged care. In order to better meet current and future challenges, the Australian Government now prepares 5-yearly Intergenerational Reports, the first of which was published in 2002. These reports focus on the implications of current and future demographic trends for economic growth, assuming current policies continue over the subsequent 40 years.

Although labour force participation rates of men and women in their early and late 60s have been steadily increasing in recent years, Treasury projections outlined in the Australian Government’s 2015 Intergenerational Report suggest that the overall proportion of Australians aged 15 years and over who are actively engaged in the workforce will decline over the next 40 years as a result of continuing population ageing (Commonwealth of Australia, 2015).

Such trends have important implications for the living standards of younger generations and associated issues of "intergenerational fairness". In their report, The Wealth of Generations, Daley, Wood, Weidman, and Harrison (2014) provided evidence suggesting that older Australians tend to be not only considerably better off financially than younger generations, but most of the growth in wealth that occurred in the decade since the new millennium went to the older generation.4 In addition, they point out that government expenditure on pensions and services, especially for older households, has increased, with much of the increase being paid for by budget deficits, the costs of which would be incurred by future generations. In their view:

There are fundamental issues of intergenerational fairness if future taxpayers are forced to bear the burden of today’s spending that they neither have a say in, nor benefit from. (Daley et al., 2014, p. 29)

The then Prime Minister of Australia, The Hon. Tony Abbott MP, summed up the situation in more controversial terms, describing it as one of intergenerational theft:5

Reducing the deficit is the fair thing to do—because it ends the intergenerational theft against our children and grandchildren. (Abbott, 2015)

Intergenerational conflict?

Do these wealth and government spending trends foreshadow a growing falling out between the generations? Potter (2014) argued this, as summarised by the title of his article Australia’s Next Battleground: Generational Conflict. So too does Spies-Butcher (2014) in his article Generational War: A Monster of Our Own Making, and Schipp (2016), whose article Is it Generational Warfare, or Generation Not-Share? begins with the statement: "Locked out of housing, jobs and a free education? Blame your parents."

Current evidence for intergenerational conflict in Australia is by no means clear-cut, though there is considerable evidence that negative stereotypes about older people are entrenched, affecting the way older people tend to be treated, for example, by healthcare and employment sectors, with repercussions for their wellbeing (see Australian Human Rights Commission, 2013, 2015, 2016; Chi-Wai, Warburton, Winterton, & Bartlett, 2011; Minichiello, Browne, & Kendig, 2000).

Using data from an Australian survey of around 1,500 people aged 18 years and over, Kendig, O’Loughlin, Hussain, Heese, and Cannon (2015) found that most respondents believed there was some degree of conflict between older people and younger people, with more than half in all age groups describing the conflict as "not very strong". Nearly half of those aged under 30 years believed that the life-long opportunities for baby boomers were worse than those for younger people, while 55% in this age group believed that "older people" (undefined) were getting less than their fair share of government benefits and only 4% believed that they were getting more than their fair share.

Hodgkin (2014) focused on answers to a different set of questions in the same survey as that used by Kendig et al.6 She found widespread support for the idea of the state directing considerable resources towards the support of elderly people. Most respondents in her study (85%) agreed that the government should provide home care and/or institutional care for elderly people in need, and most (80%) agreed that the government should pay an income to those who had to give up working or reduce their working time to care for a dependent person.

Flows of intergenerational support

Regardless of whether intergenerational conflict at this macro level is brewing, the same may not necessarily apply at the micro level—that is, within families. In fact, the above-mentioned previous research regarding older people’s relative wealth and extended years of good health suggest that they would have an increased capacity to support their adult children in financial and practical ways.

Such support appears to be occurring, in line with changing needs of young adults. For example, increasing proportions of young adults are remaining in, or returning to, the parental home for a variety of reasons, especially for the pursuit of tertiary education (ABS, 2009; Baxter, 2016; Flatau, James, Watson, Wood, & Hendeershott, 2007). When the younger generation of parents separate, the older generation may also house the grandchildren on a part- or full-time basis (see Burn & Szoeke, 2016). Furthermore, grandparents are important providers of informal childcare, especially when the children are under 3 years old. Baxter (2013) reported that around four in 10 children under 3 years of age with employed mothers were cared for by a grandparent at some time during the week. Competing with this opportunity, however, is the trend for older people to remain in paid work.7

The tables can be turned as disability or frailty develops in the older generation, particularly if there is no partner to care for the older parent in need. According to an ABS 2012 survey, 90% of people aged 65 years and over live in a private dwelling, with 77% of those aged 85 years and over doing so (ABS, 2013a). One-third of people aged 65 years indicated that they required some assistance with personal activities (e.g., health care, mobility tasks, property maintenance and household chores).

The provision of informal care for elders is particularly gendered. After female partners, daughters are the most common source of informal care. Of all adult children aged 45–64 years who were primary carers in the 2012 survey, 73% were daughters. Of carers in this age group, 47% lived with the parent receiving care.8>

Although there is considerable evidence that many younger Australians are supporting their elderly parents, Hodgkin’s (2014) study suggests that there is a limit to how much support can be expected from close relatives towards elderly people. For example, two in three respondents in her study rejected the notion that "Care should be provided by close relatives of the dependent person, even if this means they have to sacrifice their career to some extent".9

How equal is the exchange occurring to and from elderly parents? Based on a study of intergenerational transfers of money and time (including babysitting) occurring in 10 European countries, Albertini, Kohli, and Vogel (2007) concluded that, consistent with earlier European studies, downward flow of support (from older parents to their adult children) tends to be greater than upward flow (from adult children to their parents). Although weaker, this trend was apparent where the parents were in the oldest age group (70 years and over). Many adult children would also be parents. As such, their responsibilities towards their own children would generally take precedence.10

Albertini et al. (2007) also maintained that the impact of welfare state provisions on intergenerational transfers is complex. For example, they argued that the capacity of upward financial support may have eroded through the provision of welfare state provisions, but public pension incomes and health care coverage may enable older people to provide financial support to adult children.

Norms and behaviour, of course, would also vary according to broader cultural values. For example, compared with other Australians, overseas-born Australians with a non-English-speaking background appear to be more likely to place greater reliance on familial support rather than the state, and a lower emphasis on the value of personal autonomy (see Sawrikar & Katz, 2008).11

Views about parents and their adult children

To examine the views of Australians about the obligations of parents and their adult children, we used data from the 2012 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA).12 Questionnaires were sent by mail in four waves during 2012–13 to random samples of people drawn from the Australian Electoral Roll. In total, 1,588 persons aged 18 years and over (687 men and 858 women) returned a completed questionnaire.13 This represented a response rate of 34%.

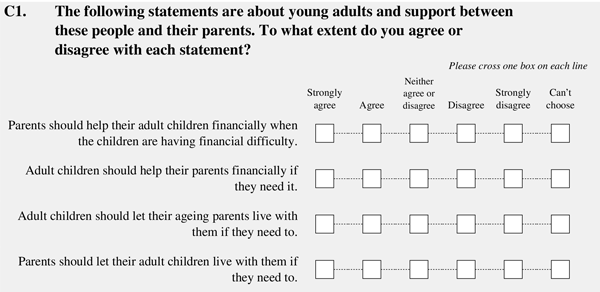

Figure 1 provides the relevant extract from the AuSSA questionnaire which sought views about intergenerational support obligations. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with four statements, each of which maintained that one party (parents or adult children) should provide support to the other party, if the latter needed such support. The first two issues focused on the provision of financial support, and the second concerned sharing accommodation—that is, that parents or adult children should allow the other party to live with them.

Figure 1: Sample question from AuSSA 2012

We have classified the second response option ("Agree") as reflecting moderate agreement, and the fourth ("Disagree") as reflecting moderate disagreement. We also refer to "agreement" and "disagreement" in general (or "acceptance" and "rejection" of a statement), ignoring the strength of the stance taken.

The following discussion focuses first on the views of all respondents, then on views according to the respondents’ gender, age, educational level, parental status (i.e., whether or not the respondents were parents), and country of birth.

Views of all respondents

Figure 2 depicts the patterns of results for the entire sample. Respondents most commonly indicated moderate agreement with each statement (taken separately). Only 1–2% of respondents expressed strong disagreement with each statement, whereas 5–6% indicated strong agreement. All four statements were more likely to generate a neutral or ambivalent stance than to be rejected.

Figure 2: Views about the four intergenerational support issues, 2012–13: Survey responses

Reading from the top of Figure 2 downwards, it can be seen that patterns of answers for the first three statements were similar, and respondents were considerably more likely to agree than disagree with the statements. This is not the case for the last issue: that adult children should let their vulnerable ageing parents live with them.

When the proportions of respondents expressing strong and moderate stances were combined:

- 59% agreed that parents should provide needed financial support to their adult children if they were in financial difficulty;

- 64% agreed that adult children should provide financial support to their parents if they needed it;

- 63% agreed that parents should allow adult children to live with them if they needed such support; and

- 11–13% of respondents disagreed with these three statements (taken separately) and 26–28% took an uncommitted or ambivalent stance.

On the other hand, just under half the respondents (47%) agreed that adult children should let their ageing parents live with them in cases of need, while 33% neither agreed nor disagreed, and 20% disagreed.

Overall, then, there was greater support for "downward" (i.e., from parents to adult children) than "upward" (i.e., from adult children to parents) support regarding meeting accommodation needs, but similar levels of agreement with "downward" and "upward" support in relation to meeting financial needs.

For simplicity, the remaining sets of analysis focus on rates of agreement only.

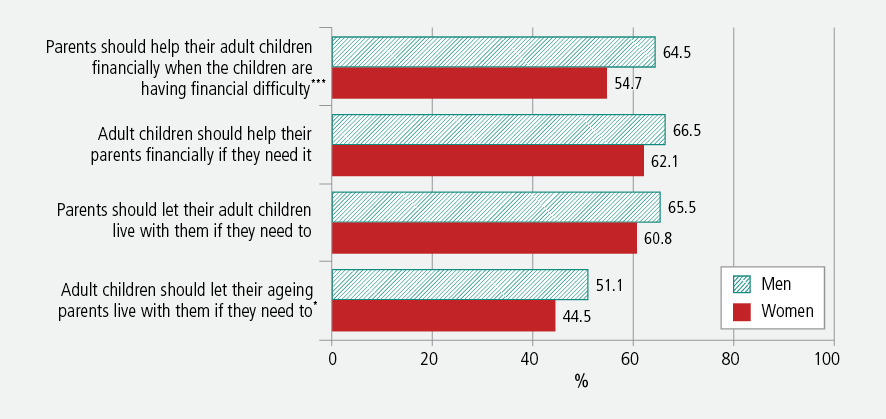

Views according to gender

Figure 3 shows that the overall patterns of trends for men and women were fairly similar, though men seemed more inclined than women to agree with each statement.

Figure 3: Percentage of respondents who agreed with each statement by gender, 2012–13

Chi-square test was applied for association between responses and gender for each statement (* p < .05; *** p < .001)

- Most men and women agreed that, where the potential recipient needed the help, each generation ought to provide the other with financial assistance, and parents should let their adult children live with them.

- The rates of agreements with the statements were lowest in relation to whether adult children should let their ageing parents live with them, if the parents needed this. This pattern applied to both men and women. Only half of the men and 45% of the women agreed with this statement.

Both men and women therefore appeared more likely to agree that parents should allow their adult children to live with them if needed rather than to agree that adult children held this obligation in relation to their elderly parents.

Regarding financial needs, however, a higher proportion of women were in favour of "upward" than "downward" support (62% vs 55%), while similar proportions of men (67% and 65%) were in favour of financial support flowing in the two directions.

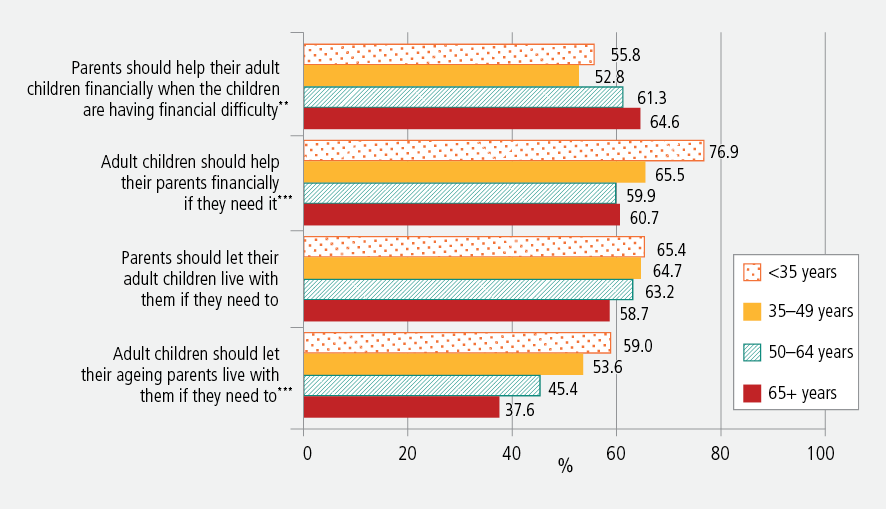

Views according to age

Figure 4 shows the extent to which patterns of answers varied according to respondents’ age (under 35 years, 35–49 years, 50–64 years and 65 years and over).

Figure 4: Percentage of respondent who agreed with each statement by age, 2012–13

Note: Chi-square test was applied for association between responses and age groups for each statement (* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001)

- Unlike the other three patterns of answers, higher proportions of respondents in the two oldest groups (aged 50 years or more) agreed that parents ought to help their adult children financially should the latter face financial difficulties (61–65% vs 53–56%), with those aged 35–40 years being the least likely to support this.

- Agreement rates concerning the other three issues tended to decrease with increasing age, with the greatest age-related differences emerging for the second and fourth issues, both of which focused on adult children’s responsibilities towards their ageing parents.

- The youngest respondents (those under 35 years old) were particularly likely to endorse the statement that adult children should support their ageing parents financially should the latter need this. Respondents aged 65 years and over were the least likely to agree with the statement. This viewpoint was endorsed by just over three-quarters (77%) of the youngest group and around three in five respondents (60–61%) in the two oldest groups.

- Whereas close to 60% of respondents in the youngest group agreed that adult children should allow their ageing parents to live with them, less than 40% of respondents in the oldest group endorsed this statement.

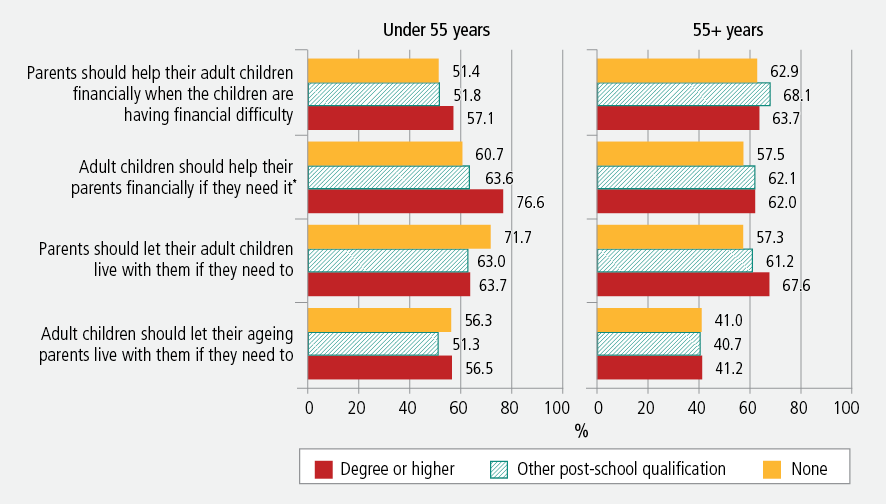

Views according to educational attainment

Because educational attainment varies strongly according to age,14 we examined links between views and education for respondents under 55 years old and those 55 years and over, using the following educational categories: a tertiary degree or higher qualification (here referred to as having a degree), having some other post-school qualification (such as a trade certificate or diploma), and having no post-school qualifications (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Percentage of respondents who agreed with each statement by education and age, 2012–13

Note: Chi-square test was applied for association between responses and education for each statement (* p < .05 for under 55 years)

Of respondents aged under 55 years:

- Those with a degree were more likely than others to agree that adult children should provide financial support to their parents if they needed it (77% vs 61–64%), and to agree that parents should help adult children financially (57% vs 51–52%), though differences for the latter issue were not statistically significant.

- Compared with the two groups with a post-school qualification, a higher proportion of those without any such qualification believed that parents should let their adult children live with them if they needed this (72% vs 63–64%), though the differences were not statistically significant.

- Similar proportions across the three education groups agreed that adult children should let their ageing parents live with them should they need to do so (51–57%).

Of the respondents aged 55 years and older:

- Views on these four matters did not vary significantly according to educational status for the older respondents.

- Although not significant, the largest difference in views concerned parents allowing their adult children to live with them: 68% of those with a degree and 57% of those with no post-school qualification believed that parents should provide this support if needed.

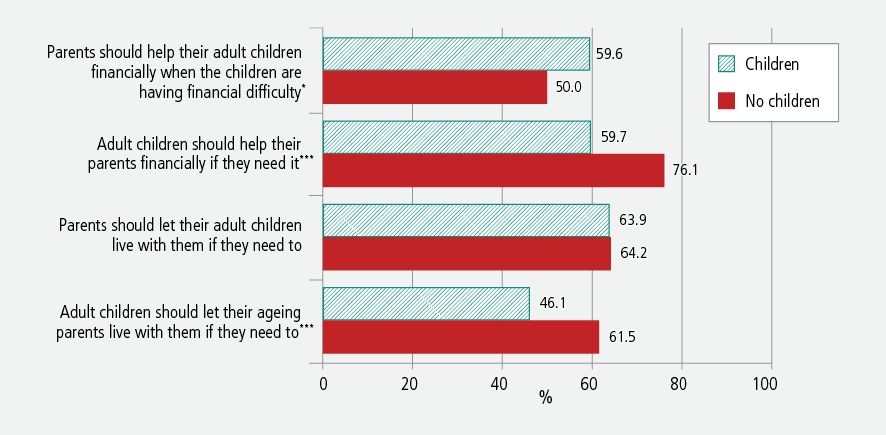

Views by whether ever had children

Issues concerning the responsibilities of parents towards adult children would be more personally relevant (i.e., less "academic" or "hypothetical") to respondents who are parents than to those who have never had children. On the other hand, with the unlikely exception of any respondent whose parents had died when they were children, the responsibilities of adult children to their parents would hold some personal relevance. Because 21% of respondents under 35 years old had had children, and the vast majority of those aged 65 years and over (89%) were parents, the following analysis (see Figure 6) focuses on the views of parents and non-parents aged 35–64 years.

Figure 6: Percentage of respondents who agreed with each statement by whether they had had a child, respondents aged 35-64 years, 2012–13

Note: Chi-square test was applied for association between responses and whether had children for each statement (* p < .05; *** p < .001)

- Similar proportions of parents and non-parents (around two in three) agreed that parents should let their adult children live with them if these children needed this.

- Parents were more inclined than non-parents to think that parents should provide financial support to their vulnerable adult children (60% vs 50%).

- Parents were less inclined than non-parents to accept the notion that adult children held responsibilities to their parents regarding both forms of support: financial (60% vs 76%) and accommodation (46% vs 62%).

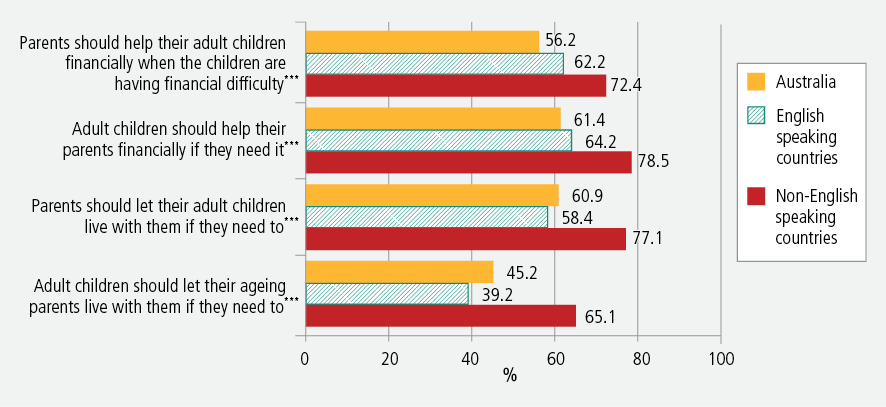

Views by country of birth

Intergenerational exchange practices appear to vary according to cultural background. For instance, Sawrikar and Katz (2008) concluded that overseas-born Australians with a non-English-speaking background appear to place greater reliance on familial support rather than the state and lower emphasis on the value of personal autonomy, compared with other Australians. For this reason, we compared the views of people who were born in Australia, in another country where English is the main language (here referred to as "another English-speaking country"), and in a country where the main language is not English (here called "non-English-speaking counties") (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Percentage of respondents who agreed with each statement by country of birth, 2012–13

Note: Chi-square test is applied for association between responses and country of birth for each statement (*** p < .001)

- Respondents who were born in a non-English-speaking country were the most likely of the three groups to agree with each statement.

- Of the four statements, respondents in all three groups were least likely to agree with statement that adult children should let their ageing parents live with them.

- Nevertheless, most respondents from non-English-speaking countries (65%) agreed with this statement.

- Only 39% of those born in another English-speaking country and 45% of Australian-born respondents believed that adult children held this responsibility.

- Each of the other three statements (that parents and adult children should provide financial support to the other if needed, and that parents should let their vulnerable adult children live with them) was supported by over 70% of those from a non-English speaking country, 58–64% of those born in another English-speaking country, and 56–61% of those born in Australia.

Controlling for inter-relationships between the characteristics examined

Although we took some account of age in the analysis of trends relating to educational attainment and parenting status, each of the above-mentioned variations in views across the subgroups may have been largely a function of other factors examined in this analysis (and/or factors that were not included in this analysis—an issue not addressed here).

Logistic regression was therefore applied to the data to identify whether views varied according to one of the factors examined, when the effects of the other factors were controlled.15 The factors were: gender, age (four subgroups), educational attainment level (three subgroups), whether a parent or not (two subgroups), and country of birth (three subgroups). See the Table of results in Appendix A.

- For each of the four issues, rates of agreement varied significantly according to gender and country of birth.

- Women were less likely to agree with each statement than men.

- Respondents born in non-English-speaking countries were more likely than those born in Australia to agree with each statement.

- No significant differences emerged in the agreement rates of respondents born in other English-speaking countries and those born in Australia.

Rates of agreement on three of the four issues varied significantly according to parental status. Compared with the parents, those who had never had children were:

- less likely to agree that parents should help their adult children financially if needed;

- more likely to agree that adult children should help their parents financially and let their ageing parents live with them if needed; and

- equally likely to agree with the statement that parents should let their adult children live with them where needed.

Views on only one issue varied significantly according to age and education.

- Respondents aged 65 years and over were the only group that was significantly less likely than those aged under 35 years to agree with the statement that adult children should let their ageing parents live with them.

- Compared with respondents with a degree, those with no post-school qualifications were less likely to agree that adult children should help their parents financially if they needed this support.

Summary

This paper focuses on beliefs about the financial and accommodation obligations of parents and adult children towards each other, where needs for support in these areas prevailed.

- Most respondents agreed with statements that, under such circumstances, parents ought to provide financial support to their adult children and vice versa, and parents ought to let their adult children live with them.

- On the other hand, just under half agreed that adult children should let their ageing parents live with them.16

- Those who did not agree with these various statements were more likely to provide a neutral / ambivalent stance than to disagree with the statements.

Agreement rates were compared across the following demographic characteristics (gender, age, education by age, parenting status, and country of birth), with the potential inter-relationships between these factors being controlled in the last set of analysis, through application of multivariate analysis. For the most part the two sets of analyses yielded very similar results.

Overall men and women shared similar views on obligations concerning the provision of financial and accommodation support between parents and adult children. Nevertheless, men appeared more inclined than women to endorse each statement.

Views about intergenerational support varied somewhat with age.

- The youngest groups were more in favour of adult children supporting elderly parents financially than the reverse.

- Respondents aged 50 years and older were more likely than those who were younger to agree that parents ought to help their adult children financially should the latter face financial difficulties.

- Although there was tendency with more acceptance of "downward" than "upward" accommodation support, this pattern was considerably more marked for respondents aged 50 years and older.

- Respondents aged 65 years and over were the least likely to agree that adult children should let their ageing parents live with them if they needed this.

Education appeared to have little bearing on views about intergenerational support. However, among respondents aged under 55 years, those with a degree were more likely than others to agree with the notion that adult children should help their parents financially if they needed it.

Views about intergenerational support varied with parental status.

- Parents were more inclined than non-parents to think that parents should provide financial support to their vulnerable adult children.

- But parents were less inclined to accept the notions that adult children ought to support their parents either financially or by letting them to live with them if they needed to do so.

Views on intergenerational support also varied according to the country of birth measure.

- Respondents with a non-English-speaking background were more likely than those who were born in Australia or in an other English-speaking country to endorse both "upward" and "downward" support regarding the financial and accommodation issues addressed. The different views were particularly marked in relation to accommodation support for ageing parents.

While some authors have argued that intergenerational conflict will intensify at the macro-level, with younger adults resenting their relatively low financial and material opportunities in life, this paper suggests that the notion intergenerational solidarity is strong within families.

The monitoring of views on such issues is important to ensure that policies are in place to promote intergenerational solidarity. Such views may well change in line with changing family trends (e.g., rates of parental separation and fertility trends), changing levels of state support provided to older and younger generations,17 likely increases in life expectancy (see ABS, 2013b), and advances in technologies that help elderly people remain in their own homes for longer.

Furthermore, inter-generational exchanges within families appear to be not only relevant for the wellbeing of individuals and their families, but also for social policy issues and intergenerational solidarity at the macro level (see Albertini et al., 2007). Policy-makers, researchers, and families themselves need to "watch this space" at both macro and micro levels.

References

- Abbott, T. (2015, 2 February). Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s speech from the National Press Club in Canberra on February 2. The Daily Telegraph. Retreived from: <www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/prime-minister-tony-abbotts-speech-from-the-national-press-club-in-canberra-on-february-2/news-story/e978c62e44518d9613f132269973cad8>

- Albertini, M., Kohli, M., & Vogel, C. (2007). Intergenerational transfers of time and money in European families: common patterns – different regimes? Journal of European Social Policy, 17(4), 319–344.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2009). Home and away: The living arrangements of young people. Australian Social Trends June 2009 (Cat. No. 4102.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from: <www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/LookupAttach/4102.0Publication30.06.096/$File/41020_Homeandaway.pdf>

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012a). 2011 Census of Population and Housing – Basic community profile – Tables B04 and B40b (Cat. No. 2001.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from: <www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/communityprofile/0?opendocument&navpos=220>

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012b). Reflecting on a nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012–2013: Who are Australia’s older people? (Cat. No. 2071.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from: <www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/2071.0main+features752012-2013>

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013a). Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, 2012 (Cat.No. 4430.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from: <www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4430.0>

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013b). Population projections, Australia. 2012 (Base) to 2101 (Cat. No. 3222.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015a). Australian demographic statistics, June 2015 (Cat. No. 3101.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from: <www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/801757AC98D5DE8FCA257F1D00142620/$File/31010_jun%202015.pdf>

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015b). Population by age and sex, Regions of Australia, 2014 (Cat. No. 3235.0). Retrieved from: <www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/3235.02014?OpenDocument>

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016a). Australian demographic statistics, September quarter 2015 (Cat. No. 3101.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016b). Labour force, Australia, detailed - electronic delivery (Cat. No. 6291.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2013). Fact or fiction? Stereotypes of older Australians. Sydney: AHRC. Retrieved from: <www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/age-discrimination/publications/fact-or-fiction-stereotypes-older-australians-research>

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2015). National prevalence survey of age discrimination in the workplace 2015. Sydney: AHRC. Retrieved from: <www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/AgePrevalenceReport2015.pdf>

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2016). Willing to work: National Inquiry into Employment Discrimination against Older Australians and Australians with Disability. Sydney: AHRC. Retrieved from: <www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/Willing_to_work_report_2016_AHRC.pdf>

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2014). Healthy life expectancy in Australia: patterns and trends 1998 to 2012 (Bulletin 126). Catalgoue no. AUS 187. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from: <www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129549632>

- Baxter, J. (2013). Child care participation and maternal employment trends in Australia (Research Report No. 26). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from: <www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/resreport26/index.html>

- Baxter, J. (2016). The modern Australian family (Facts Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Burn, K., & Szoeke, C. (2016). Boomerang families and failure-to-launch: Commentary on adult children living at home. Maturitas, 83, 9–12.

- Cass, B. (1995). Cultural diversity and challenges in the provision of health and welfare services: Towards social justice: Employment and community services in culturally-diverse Australia. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Social Services—Settlement and Multicultural Affairs.

- Chi-Wei, L., Warbrton, J., Winterton, R., & Bartlett H. (2011). Critical reflections on a social inclusion approach for an ageing Australia. Australian Social Work, 64(3), 266–282.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2015). 2015 Intergenerational Report: Australia in 2055. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from: <www.treasury.gov.au/PublicationsAndMedia/Publications/2015/2015-Intergenerational-Report>

- Daley, J., Wood, D., Weidman, B., & Harrison, C. (2014). The wealth of generations. Melbourne: Grattan Institute. Retrieved from: <grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/820-wealth-of-generations3.pdf>

- Flatau, P., James, I., Watson, R., Wood, G., & Hendeershott, P. H. (2007). Leaving the parental home in Australia over the generations: Evidence from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. Journal of Population Research, 24(1), 51–71.

- Hodgkin, S. (2014). Intergenerational Solidarity at the state and family level: an investigation of Australian Attitudes. Health Sociology Review, 23(1), 53–56.

- Kendig, H., O’Loughlin, K., Hussain, R., Heese, K., & Cannon, L. (2015). Attitudes to intergenerational equity: Baseline findings form the attitudes to ageing in Australia (AAA) study (Working Paper 2015/33). Canberra: ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research, Australian National University. Retrieved from: <www.cepar.edu.au/media/167073/33-attitudes-to-intergenerational-equity-baseline-findings-from-the-attitudes-to-ageing-in-australia-study.pdf>

- Minichiello, V., Browne, J., & Kendig, H. (2000). Perceptions and consequences of ageism: Views of older people. Ageing and Society, 20(May), 253–278.

- Morris, N. (2013, 14 March). Demographic time bomb: Government ‘woefully underprepared’ to deal with Britain’s ageing population. Independent. Retrieved from: <www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/demographic-time-bomb-government-woefully-underprepared-to-deal-with-britains-ageing-population-8533508.html>

- North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2015). Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 993–1021.

- O’Dwyer, L., Buckley, J., Feist, H., & Parker, K. (2012). Intergenerational transfers of time and money to and from the over 50s in Australia. Melbourne: National Seniors Productive Ageing Centre. Retrieved from: <www.adelaide.edu.au/apmrc/research/projects/Intergenerational_Transfers_Time_Money.pdf>

- Potter, B. (2014, 13 December). Australia’s next battleground; generational conflict. Australian Financial Review. Retrieved from: <www.afr.com/news/policy/tax/australias-next-battleground-generational-conflict-20141212-126c1h>

- Productivity Commission. (2013). An ageing Australia: Preparing for the future (Productivity Commission Research Paper). Retreived from: <www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/ageing-australia/ageing-australia.pdf>

- Sawrikar, P. & Katz, I. (2008). Enhancing family and relationship service accessibility and delivery to culturally and linguistically diverse families in Australia (AFRC Issues No. 3). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from: <aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/enhancing-family-and-relationship-service-accessibility-and>

- Schipp, D. (2016, 3 March). Is it generational warfare, or generation not-share? News.com.au. Retrieved from: <www.news.com.au/finance/real-estate/is-it-generational-warfare-or-generation-notshare/news-story/5dcaca8e9fa97a520433406e255643ee>

- Spies-Butcher (2014, 17 December). Generational war: A monster of our own making. The Conversation. Retrieved from: <theconversation.com/generational-war-a-monster-of-our-own-making-35469>

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2013). World population ageing 2013. New York: United Nations. Retrieved from: <www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf>

- van Onselen, L. (2014, 11 April). Ageing tsunami goes global. Unconventional Economist, MacroBusiness. Retrieved from <www.macrobusiness.com.au/2014/04/ageing-tsunami-goes-global/>

Appendix A: Coefficients of logistic regression results

| Parents should help their adult children financially when the children are having financial difficulty | Adult children should help their parents financially if they need it | Parents should let their adult children live with them if they need to | Adult children should let their ageing parents live with them if they need to | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| (Male) | ||||

| Female | -0.443 *** | -0.252 * | -0.301 ** | -0.338 ** |

| Age (years) | ||||

| (Under 35) | ||||

| 35-49 | -0.368 | -0.115 | -0.044 | 0.097 |

| 50-64 | -0.056 | -0.369 | -0.196 | -0.358 |

| 65+ | 0.058 | -0.262 | -0.378 | -0.700 ** |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| (Degree) | ||||

| Some qual | -0.111 | -0.252 | -0.087 | -0.037 |

| None | -0.175 | -0.411 ** | -0.009 | 0.129 |

| Parental status | ||||

| (Has had children) | ||||

| No children | -0.336 * | 0.835 *** | 0.069 | 0.549 *** |

| Country of birth | ||||

| (Aus) | ||||

| Eng-country | 0.084 | 0.174 | -0.135 | -0.254 |

| Non-Eng country | 0.661 *** | 0.896 *** | 0.806 *** | 0.966 *** |

| Constant | 0.809 *** | 0.881 *** | 0.814 *** | 0.103 |

| Number of respondents | 1378 | 1381 | 1377 | 1357 |

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Reference categories are shown in brackets.

Endnotes

1 Consistent with ABS classifications, the term "baby boomers" is here used to refer to people born between 1946 and the mid-1960s (ABS, 2015a, 2015b).

2 Facilitation of planned parenthood has played a major role, especially through the introduction of the contraceptive pill in 1961 and its cost-reducing inclusion on the Pharmaceuticals Benefits Scheme in 1972.

3 Projections about future trends are based on assumptions concerning future fertility and mortality levels and migration patterns. The ABS (2013b) projections outlined here used 31 June 2012 as its benchmark. Across these periods, these projections suggest that the proportion of the population aged under 15 years will decrease from 19% to 15–18% in 2061 and 14–17% in 2101, while the proportion aged 15–64 years will decrease from 67% to 59%–61% in 2061 and 57%–59% in 2101.

4 As a caveat, Daley and colleagues noted that they focused on average trends, thereby ignoring the fact that some older people were struggling financially and some younger people were experiencing a rapid growth in wealth.

5 Address to the National Press Club <http://bit.ly/29Ru7U4>

6 The studies by Kendig et al. (2015) and Hodgin (2014) were based on data collected in the 2009 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes.

7 To encourage this trend, the age at which people can apply for the Age Pension (currently 65 years) will gradually increase to 67 years by 2023 for those born after 1956 (Australian Government Department of Human Services (2016) Age Pension). The idea of raising the pension age to 70 years by 2035 (for those born after 1965) was proposed by the Australian Government in 2014. See <www.humanservices.gov.au/customer/services/centrelink/age-pension>. In the meantime, the employment rates of men and women (especially the latter) aged 60–64 years and 65 years and over have increased since the mid-1990s (ABS, 2016b).

8 The ABS defines carers as those who provide any informal assistance (help or supervision) to an older person or someone who has a disability or long-term condition. This assistance had to have been, or be likely to be, ongoing for at least 6 months. Primary carers are those who provide the most informal assistance to someone who has a disability relating to mobility, self-care and/or communication.

9 Given the other questions asked, the dependent person in question was clearly an elderly relative.

10 This explanation is supported by a survey of respondents aged 50 years and over, conducted in three states of Australia (NSW, Qld & SA). The authors of this 2012 study, O’Dwyer, Buckley, Feist, and Parker, found that of the 26 respondents with two living parents and adult children, most of their transfers of time and money were to their children.

11 Focusing on the macro level, North and Fiske (2015) provide evidence suggesting that respect for the elderly is now weaker in countries—especially Southeast Asian countries—that emphasise collectivism and filial piety than in countries—especially Anglophone countries—that emphasise individualism. They linked this trend in part to the more rapidly ageing populations in the former countries compared with the latter. It would be interesting to see if levels of intergenerational solidarity within families in these countries yield results that are consistent with those relating to macro-level respect for elderly people.

12 The survey was conducted by the Australian Consortium for Social and Political Research Inc. (ACSPRI).The survey focused on a range of issues. The Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) developed and paid for the inclusion of some modules on family-related issues. Note that the above-mentioned studies conducted by Kendig et al. (2015) and Hodgin (2014) were based on the 2009 AuSSA survey.

13 Gender was not known for 43 respondents. The sample contained an under-representation of men, young adults, and people with no post-school qualification.

14 For example, the proportion of persons aged 25 years and older who had a degree or higher level of qualification fell with increasing age according the 2011 Census (ABS 2012a).

15 The data analyses were based on binary scores, where: 1 = agreed or strongly agreed, and 0 = other response (i.e., neither agreed nor disagreed, disagreed, or strongly disagreed).

16 These trends refer to results pertaining to each question taken separately.

17 The Australian Government is in the process of implementing a range of reforms to the aged care system, partly to ensure that the aged care system is sustainable, affordable and provides consumers with choice and flexibility. Reforms that have so far been implemented include the Consolidated Home Support Program and the Home Care Packages directed towards helping older people who need assistance to: remain in their homes; have greater say in nature and mode of delivery of services they access; and contribute to the costs of services received if they can afford this. Part of the reforms is also directed towards carers. For more details, including exemptions that apply to Western Australia and Victoria, see Aged Care Reform <www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/ageing-and-aged-care/aged-care-reform>.

Ruth Weston is the Assistant Director (Research) and Lixia Qu is a Senior Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Photo credits: Front cover (clockwise from top left: © istockphoto/kali9; © istockphoto/MariaDubova; © istockphoto/FotoCuisinette; © istockphoto/laflor. Page 2 © istockphoto/MachineHeadz. Page 10 © istockphoto/Squaredpixels.

Suggested citation: Weston, R., & Qu, L. (2016). Attitudes towards intergenerational support (Australian Family Trends No. 11). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-76016-101-9