Patterns and precursors of adolescent antisocial behaviour: Outcomes and connections

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

November 2005

Diana Smart

Download Research report

Minister's foreword

Victoria is one of the best places to raise a family because we have some of the safest homes, streets and neighbourhoods in the nation.

Early intervention is important. Experts from around the world agree that keeping young people out of trouble from an early age is the best way to help them stay on track. This is why I applaud the work of the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria for their work on the series Patterns and Precursors of Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour.

The third and final report looks at the common risk factors between young people who engage in criminal and anti-social behaviour. This report builds on the work of two previous reports, and follows more than 2000 Victorian children and their families from infancy to adulthood.

By looking at the environmental and social factors that children and families are exposed to, this study identifies patterns and behaviours that could point towards the need for early intervention strategies.

It is aimed at developing a better understanding of antisocial and criminal behaviour in young people. By identifying problems early we can prevent children from heading down the wrong path.

I congratulate both the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria on delivering this innovative research project with sound, empirically-based evidence to guide future prevention and early intervention efforts.

Tim Holding MP

Minister for Police & Emergency Services

Director's foreword

Adolescent antisocial behaviour greatly concerns governments, researchers, and community members alike. Although this issue has been the focus of intensive research over recent decades, many questions regarding the development and consequences of this type of behaviour remain to be answered. Effective prevention and early intervention efforts to avert the onset of antisocial behaviour among children and adolescents rely to a large extent on an accurate understanding of its origins and course. Thus the research contained in this report is particularly welcome.

The report "Patterns and Precursors of Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour: Outcomes and Connections – Third Report" continues the valuable work of the first two reports in this series, and marks the culmination of the collaboration between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria. It makes use of the Australian Temperament Project dataset to investigate six distinct topics relating to adolescent antisocial behaviour. This large longitudinal, community study has followed children's development over the first 20 years of life, investigating their psychosocial adjustment and wellbeing, and the influence of family and wider environmental factors via 13 waves of data collected from a representative sample of 2,443 children and parents.

The six topics addressed in the Third Report are: the continuity of persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour into early adulthood; links between antisocial behaviour and victimisation during early adulthood; associations between adolescent substance use and antisocial behaviour; the development of persistent antisocial behaviour among low-risk children; connections between motivations to comply with the law, attitudes, and antisocial behaviour; and the correspondence between official records and self reports of offending and victimisation.

I highly commend this report, which contains important new knowledge about the development of antisocial behaviour among young Australians, and its impact upon their wellbeing and adjustment. I am confident that it will provide valuable insights for policy development and practical interventions, and add substantially to our knowledge of this type of behaviour. Ultimately, through the understandings gained by research such as this, we will be able to help children to make the best start in life and promote their later positive development within the context of their family and community life.

Professor Alan Hayes

Director

Australian Institute of Family Studies

Downloads

Executive summary

This is the third and final report from the collaborative partnership between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria. It further explores issues concerning adolescent antisocial behaviour and outcomes arising from it. The research draws upon data collected as part of a unique Australian study – the Australian Temperament Project.

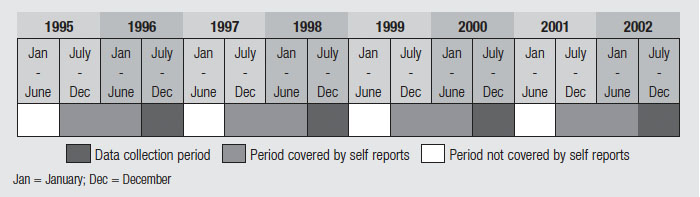

The Australian Temperament Project (ATP) is a large, longitudinal study which has followed the development and adjustment of a community sample of children from infancy to early adulthood. The study began in 1983 with the recruitment of a representative sample of 2443 infants and their families living in urban and rural areas of Victoria. Approximately 65 per cent of the sample was still participating in the project in 2004. Thirteen waves of data have been collected over the first 20 years of the children's lives, using mail surveys. Parent, teachers and the children have reported on the child's temperament style, behavioural and emotional adjustment, social skills, health, academic progress, relationships with parents and peers, and the family's structure and demographic profile.

The Third Report focuses on six distinct issues: (1) the transition to early adulthood, and the continuation, cessation and commencement of antisocial behaviour; (2) connections between antisocial behaviour and victimisation; (3) the role of substance use in the development of adolescent antisocial behaviour; (4) why do some low risk children become antisocial adolescents; (5) motivations to comply with the law, attitudes, and antisocial behaviour; and (6) concordance between official records and self-reports of offending and victimisation.

Many of the findings report the progress of the three groups identified in the First Report from this collaborative project, who displayed differing patterns of antisocial behaviour across adolescence. These were:

- a low/non antisocial group, N=844, 41 per cent male (these adolescents consistently exhibited no, or low levels of antisocial behaviour at 13-14, 15-16 and 17-18 years);

- an experimental antisocial group, N=88, 43 per cent male (these adolescents exhibited high levels of antisocial behaviour at only one time point during early-to-mid adolescence and then desisted); and

- a persistently antisocial group, N=131,65 per cent male (these adolescents reported high levels of antisocial behaviour at two or more time points, including the latest time point of 17-18 years).

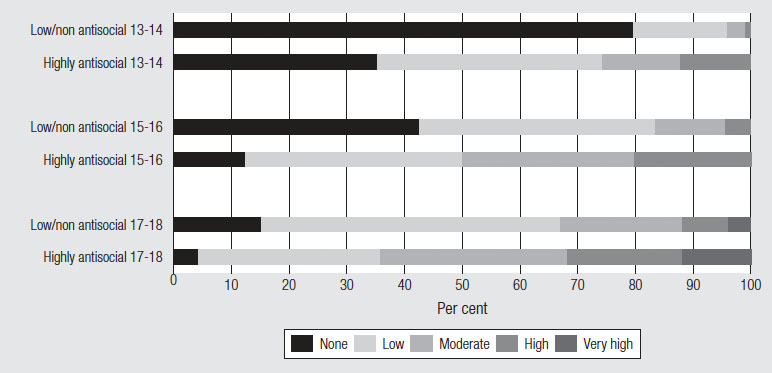

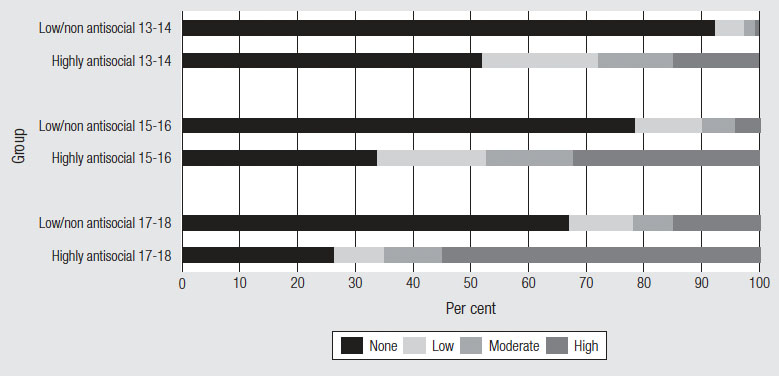

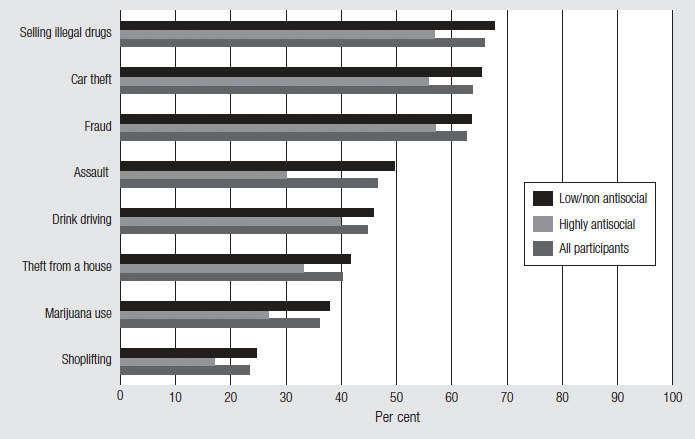

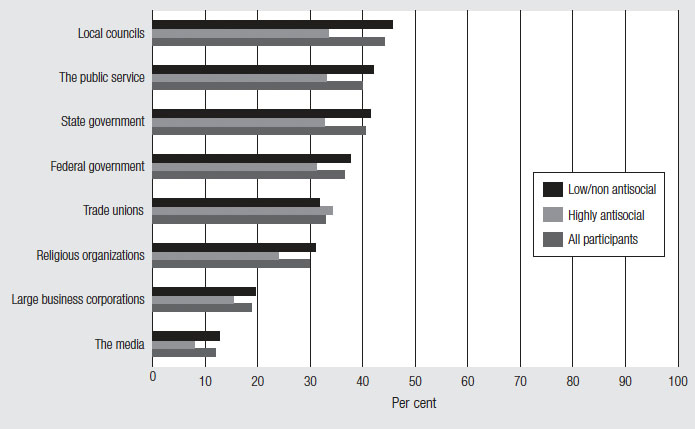

The findings concerning vicitimisation and motivations to comply with the law compare two additional groups who displayed differing patterns of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years of age: a highly antisocial group (N=177) who had engaged in three or more different types of antisocial acts in the past 12 months, and a low/non antisocial group (N=963) who had engaged in fewer than three different types of antisocial acts in the past 12 months.

Transitions to early adulthood: stability and change in antisocial behaviour

While rates of most types of antisocial behaviour are known to decrease from adolescence to early adulthood, less is known about individual trends. To what extent do young people who consistently engage in antisocial behaviour during adolescence continue their involvement in antisocial behaviour in adulthood? Do individuals who display particular types of adolescent antisocial behaviour differ in their later opportunities, experiences and wellbeing? Is there a late onset pathway to antisocial behaviour that begins in early adulthood?

Findings on these issues revealed that, first, the majority of individuals who had engaged in persistent antisocial behaviour at multiple time points during adolescence continued to display antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years (55 per cent). The considerable minority who did not maintain high levels of such behaviour (45 per cent) often reported some continuing lower frequency involvement. It did not seem that this decreasing involvement in antisocial behaviour was associated with any particular life experiences or circumstances, individual characteristics or interpersonal relationships.

Second, a small late onset antisocial group was found (N=68). This group had not engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour during early or mid adolescence, but began to display this type of behaviour for the first time during late adolescence or early adulthood. The late onset group was compared to three groups: (a) the low/non antisocial group who never displayed high levels of adolescent antisocial behaviour; (b) the persistent antisocial group; and (c) the experimental antisocial group who engaged in antisocial behaviour in early adolescence and then desisted.

Comparisons of the progress of these four groups revealed that the experimental group closely resembled the low/non group at 19-20 years, and both groups appeared to be faring well. The late onset group did not appear to experience a more difficult transition in terms of their participation in work and study, but more frequently experienced interpersonal and adjustment difficulties. The persistent group was less likely to have completed secondary schooling and to be undertaking further study by comparison with the other three groups. This group also more frequently displayed long-standing adjustment and interpersonal relationship difficulties, highlighting the long-term impact of persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour and the desirability of prevention and early intervention efforts to avert its development.

Connections between antisocial behaviour and victimisation

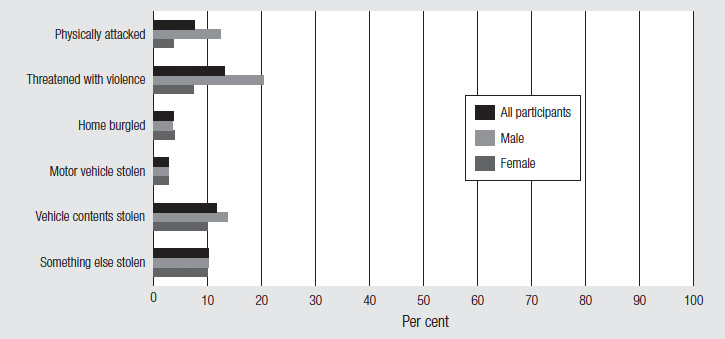

As well as being responsible for more offences than older individuals, young people experience the highest rates of victimisation, and there may be links between engagement in antisocial behaviour and the experience of victimisation. Factors implicated in the occurrence of victimisation are thought to include lifestyle characteristics and activities, and interpersonal characteristics.

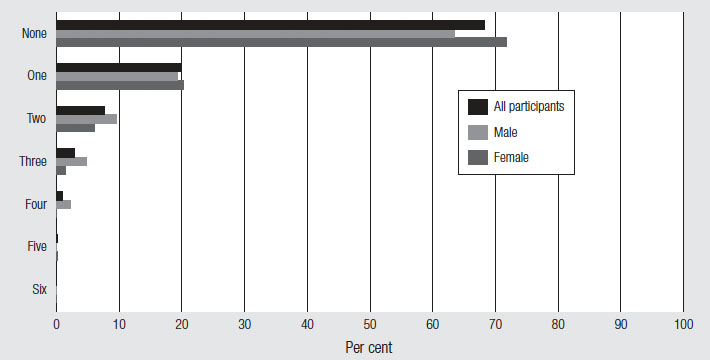

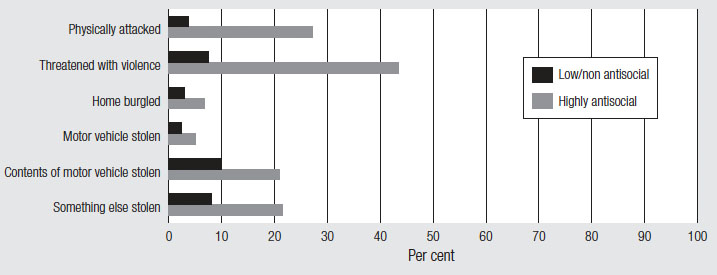

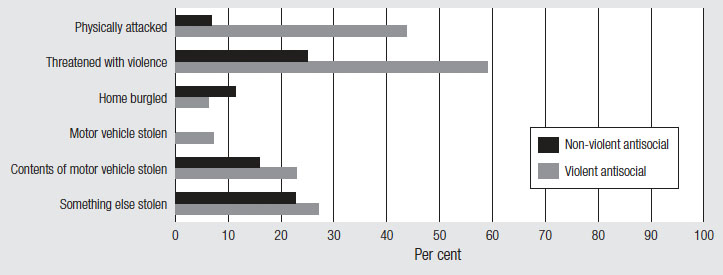

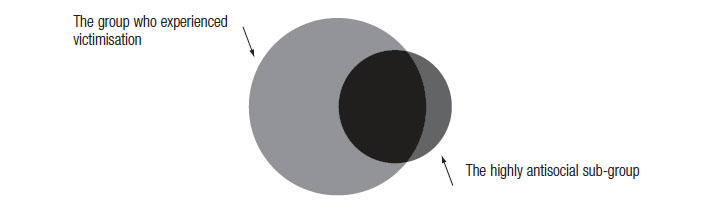

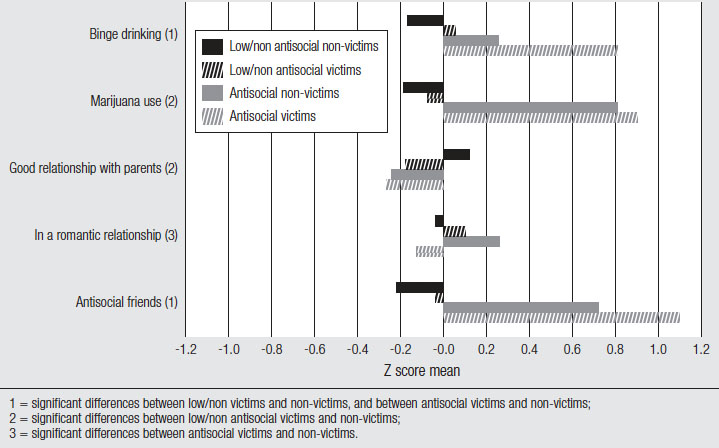

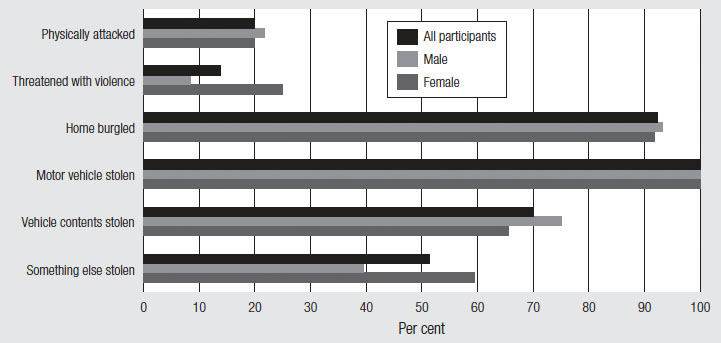

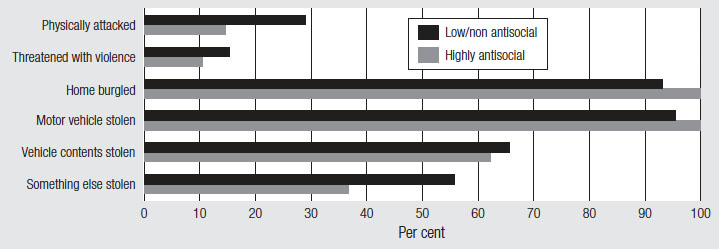

When these issues were investigated it was found that approximately one-third of the 19-20 year olds had experienced victimisation during the previous 12 months. The most frequent types of incidents reported were threats of violence, followed by theft from a motor vehicle, and other theft. The relationship between victimisation and antisocial behaviour was complex. On one hand, two-thirds of those who engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years had experienced victimisation. Furthermore, those who engaged in violent antisocial behaviour were also very likely to experience violent victimisation. On the other hand, looking at the group of young people who experienced victimisation, it was found that the majority had not engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years.

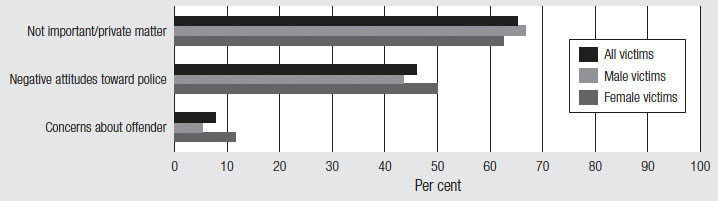

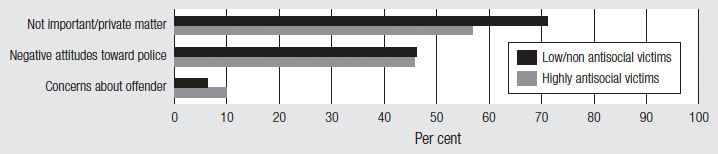

Lifestyle factors and specific social contexts appeared to increase the risk of victimisation. About half the victimisation incidents had been reported to police. The main reasons for not reporting such incidents were their perceived lack of importance, negative attitudes towards the police, or a belief that the incident was a private matter. The implications for crime prevention were highlighted and it was suggested that a clearer focus on victimisation could have dual benefits in reducing both antisocial behaviour and victimisation.

Substance use and antisocial behaviour

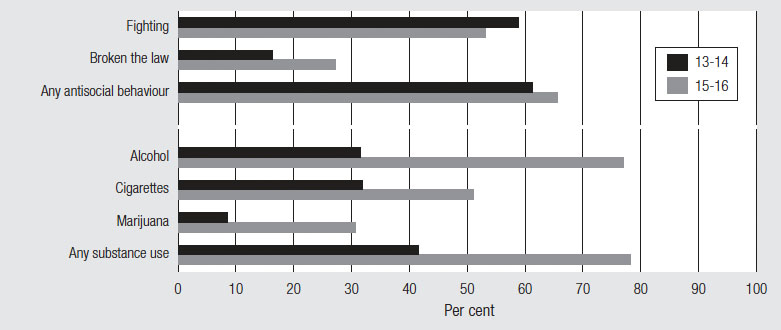

Adolescent substance use is associated with a wide range of difficulties in personal and social functioning, such as decreased educational attainment and mental health problems. It is also strongly associated with engagement in antisocial behaviour in both adolescence and later in adulthood. The overlap between antisocial behaviour and substance use was investigated, as were the role of substance use in the development of antisocial behaviour, and the influence of substance using and/or antisocial peers.

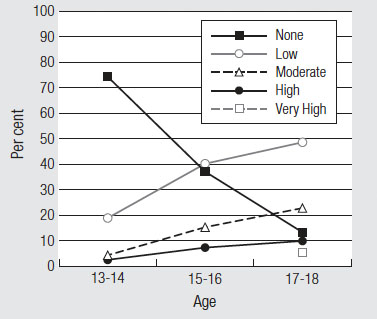

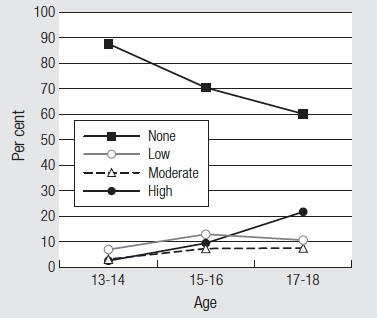

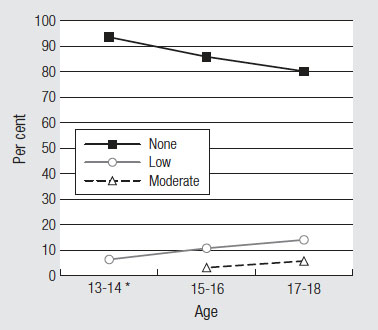

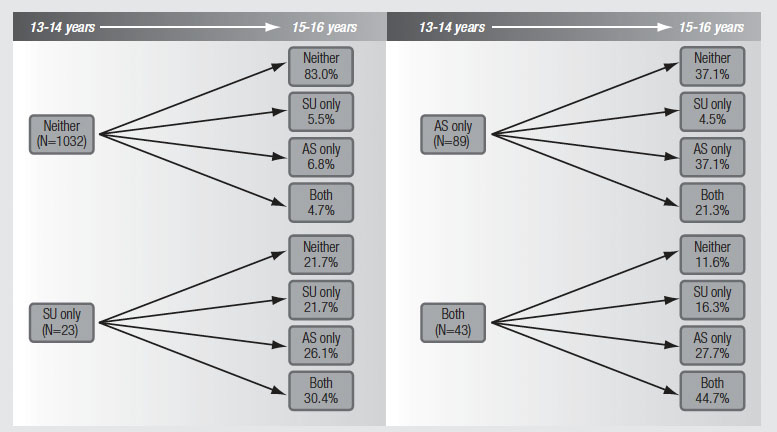

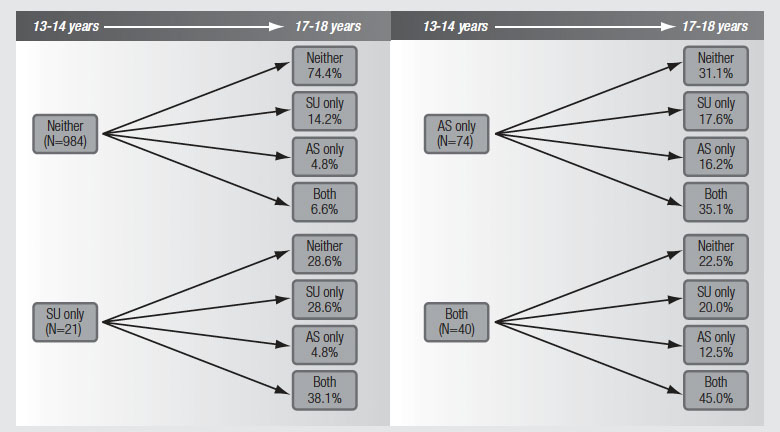

Strong links between adolescent substance use and antisocial behaviour were revealed. There was a considerable overlap between the occurrence of antisocial behaviour and substance use at the same point in time. In addition, individuals who engaged in persistent antisocial behaviour from early to late adolescence had the highest rates of all types of substance use, followed by those who engaged in experimental antisocial behaviour, while adolescents who did not engage in antisocial behaviour had the lowest rates of substance use. Investigation of across-time pathways between substance use and antisocial behaviour revealed strong bi-directional pathways between the two types of behaviours. Peers' levels of involvement in antisocial behaviour and/or substance use were closely linked to adolescents' own engagement in such behaviours.

The powerful association between antisocial behaviour and substance use found serves as a reminder that antisocial adolescents frequently experience a wide range of difficulties, underlining the need for broad- based intervention programs that assist these young people in a number of areas of their lives.

Why do some low risk children become antisocial adolescents?

The Second Report showed that while most persistently antisocial adolescents had a history of childhood problematic behaviour, a small sub-group (N=42) had relatively problem-free childhoods and first began to display difficulties during early adolescence. Their progression to persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour was unexpected, and could not have been predicted from their earlier development. Their across-time pathways, and the factors which may have contributed to a change in pathways, were investigated. As well, these individuals were followed forwards into early adulthood to investigate whether antisocial behaviour persisted or ceased, as well as their adjustment and wellbeing.

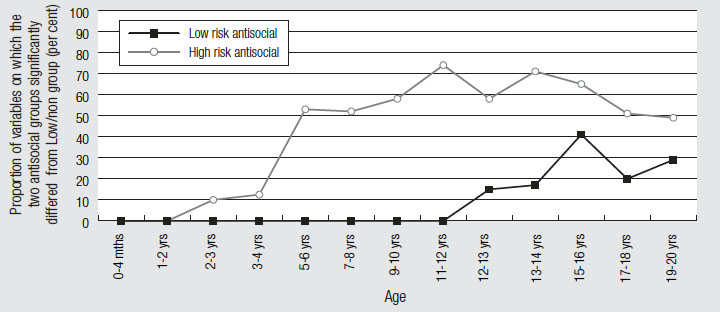

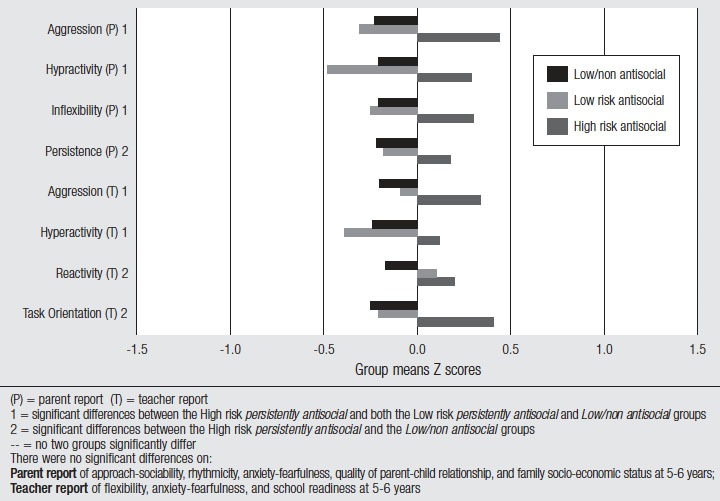

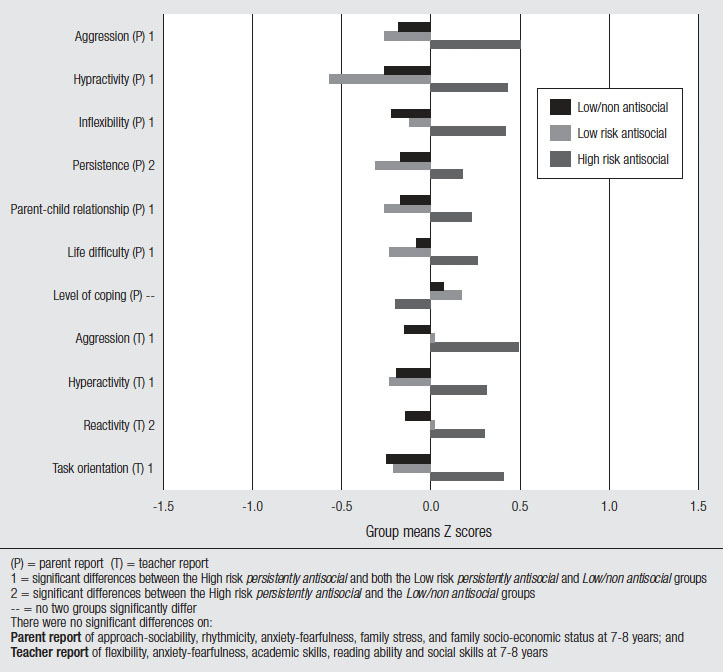

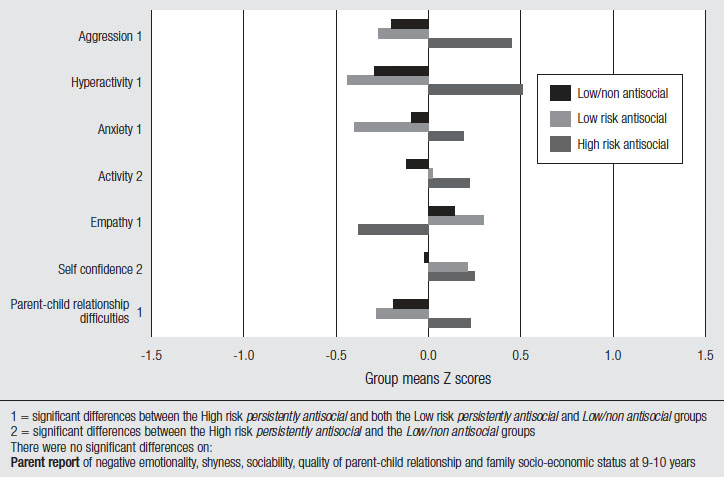

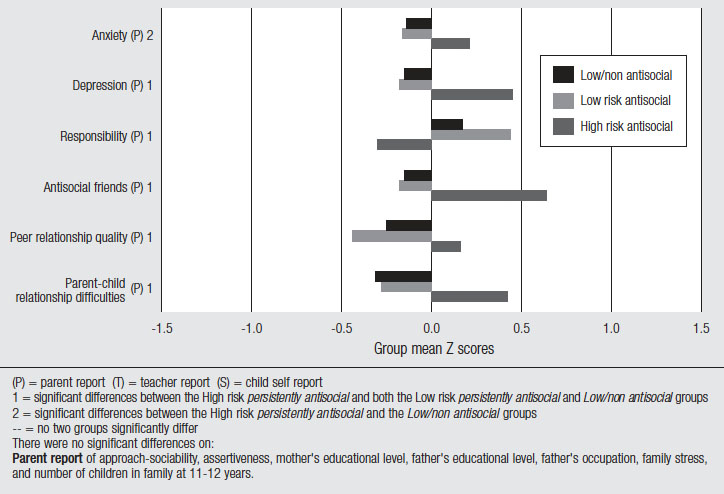

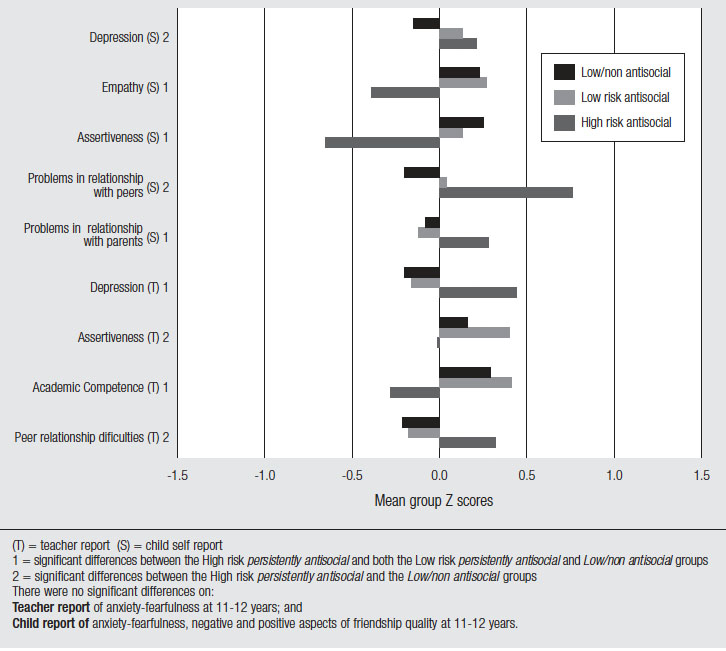

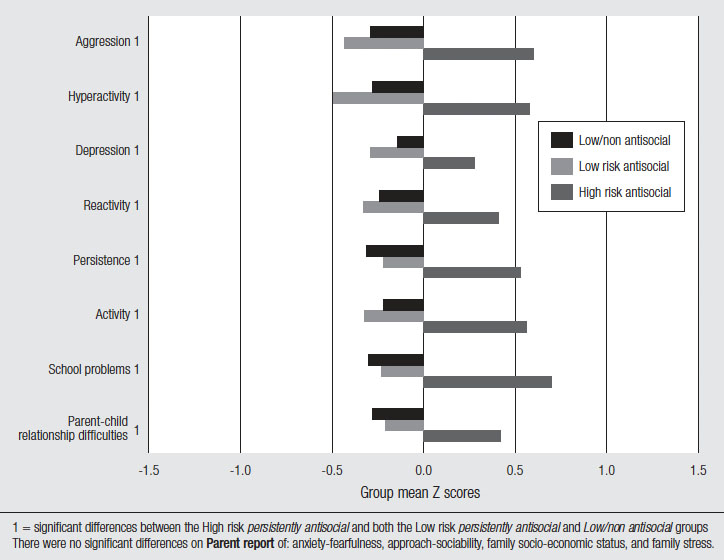

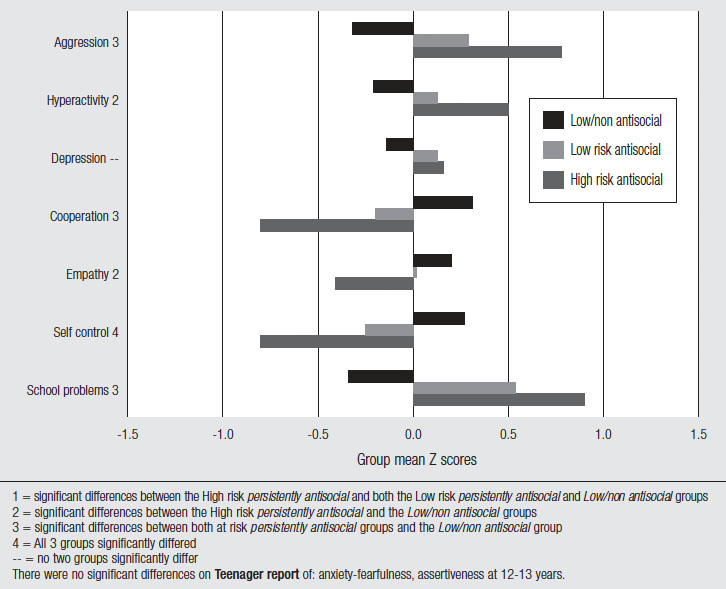

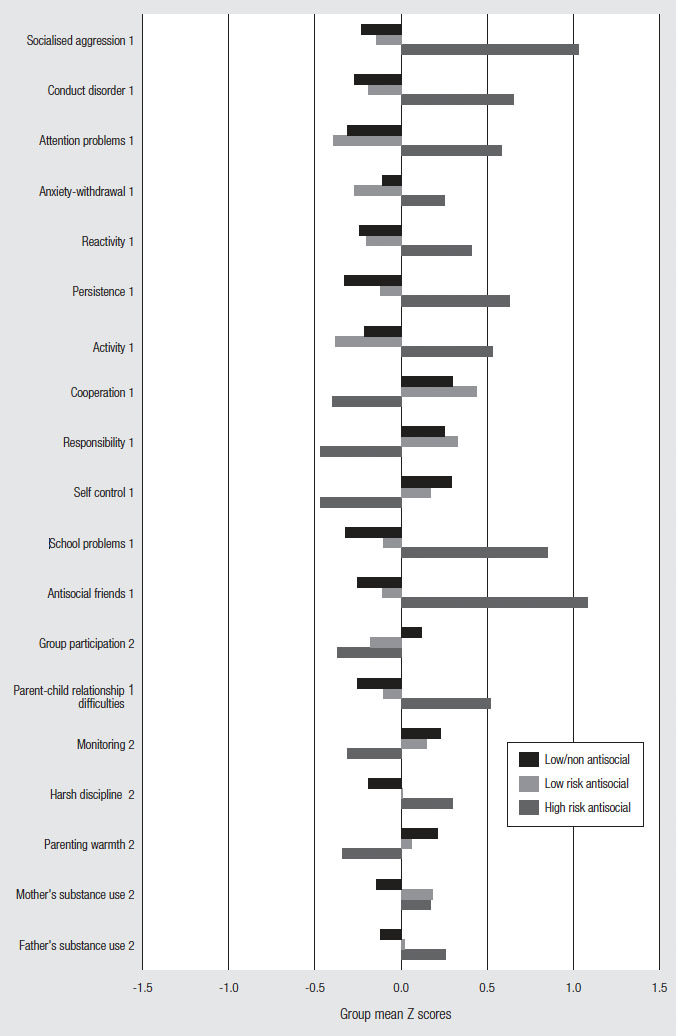

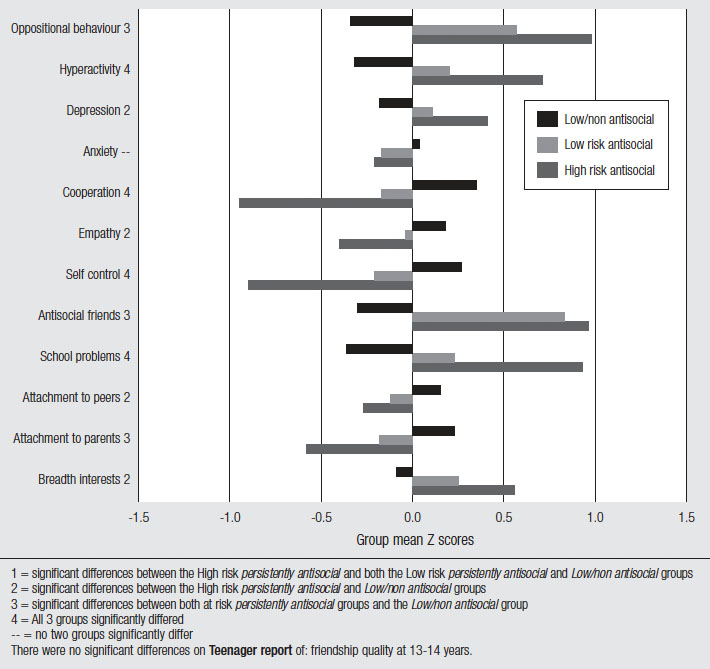

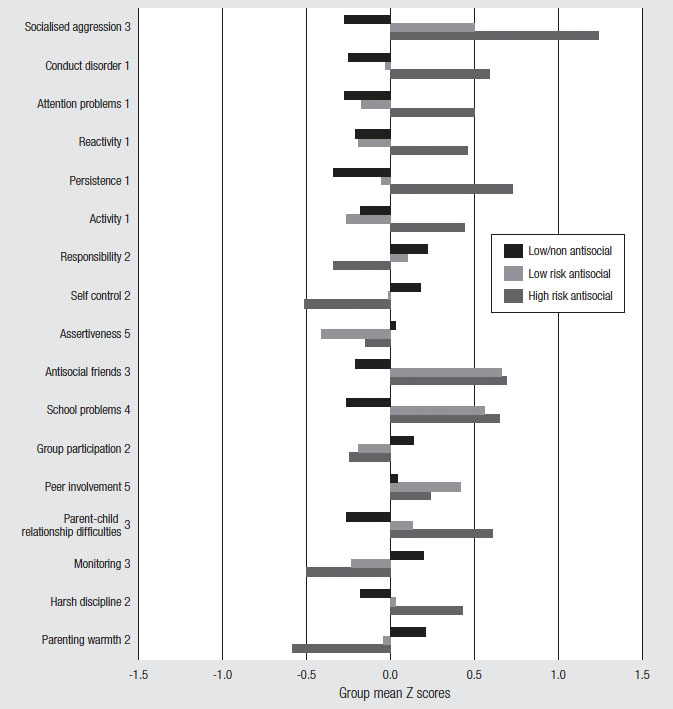

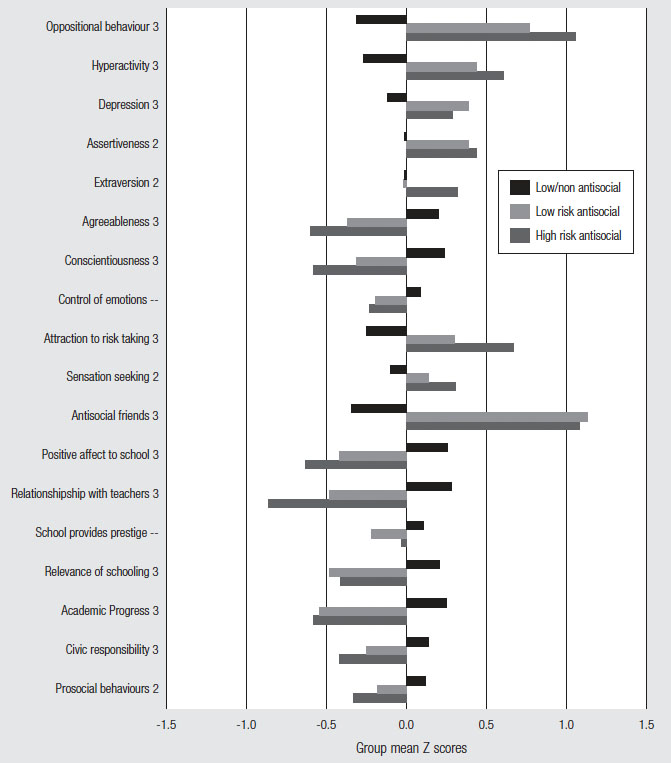

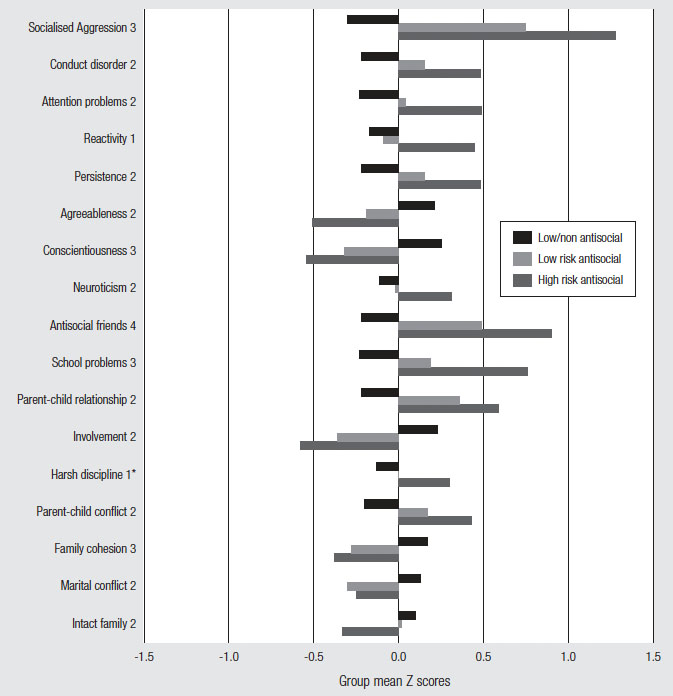

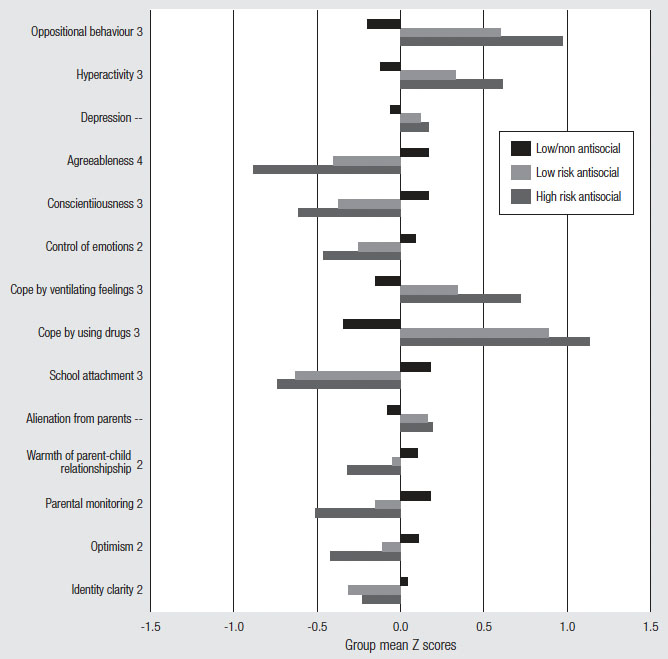

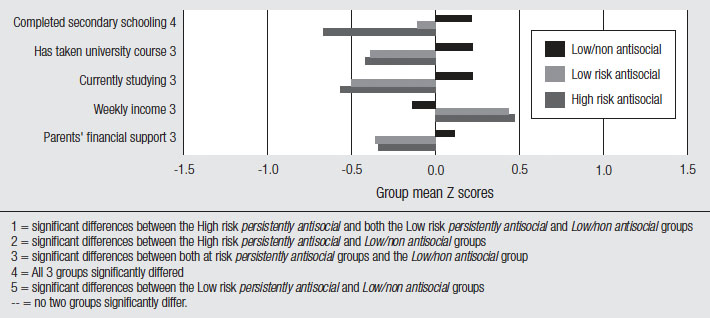

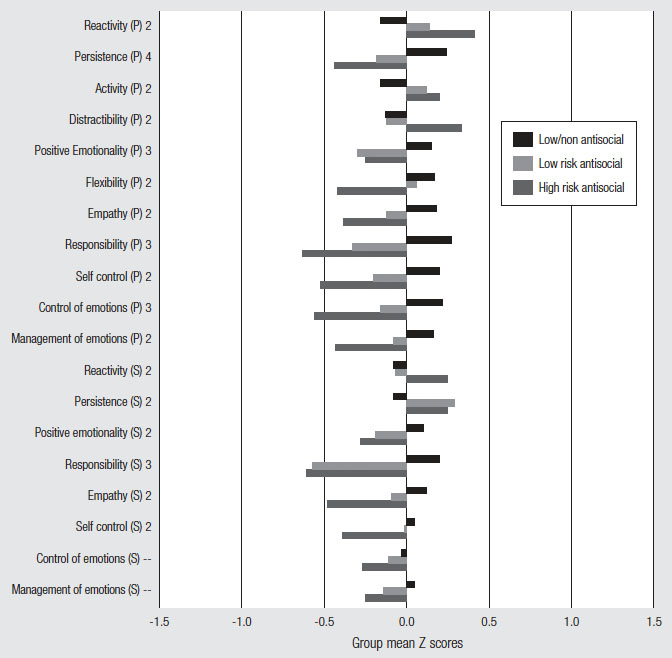

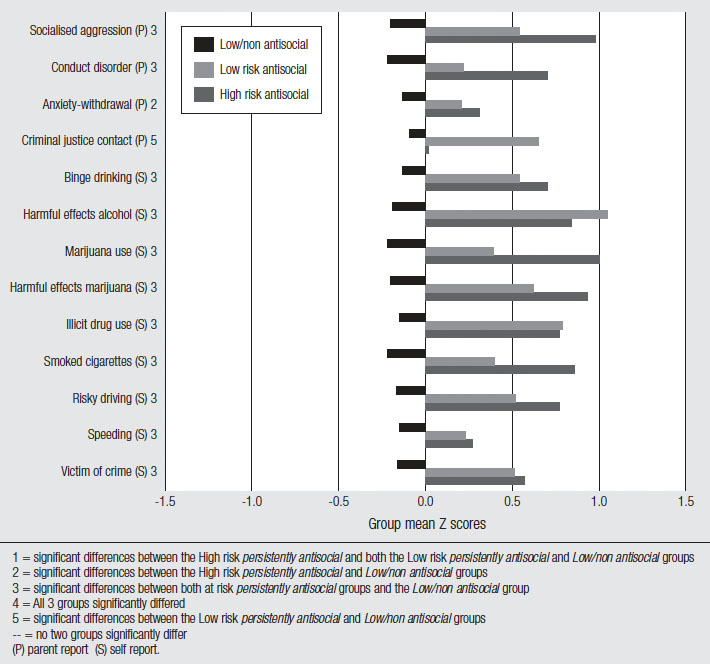

The first differences between the low risk persistently antisocial sub-group and the low/non antisocial group emerged during early adolescence, at 12-13 years (Year 7 for the great majority). Differences became more widespread during adolescence and peaked at 15-16 years of age, although numerous differences were still evident at 19-20 years. During the early secondary school years, the low risk antisocial sub-group was notably more involved with antisocial peers and less attached to school than the low/non antisocial group, They also began to display more difficult traits and behaviour as well as lower social skills. By mid adolescence there were more extensive differences between these two groups. As the low risk antisocial sub-group became more differentiated from the low/non antisocial group, it became increasingly similar to the high risk persistently antisocial group (N=89). However, generally the high risk antisocial sub-group displayed more severe and diverse difficulties than the low risk antisocial sub-group, and thus appeared to be faring worse at this age.

The majority of individuals from both antisocial sub-groups (low risk and high risk) continued to engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood (19-20 years). The differences between the low risk antisocial and low/non antisocial groups found in adolescence were again evident in early adulthood. Thus, the low risk antisocial sub-group more frequently engaged in problematic and risk-taking behaviours such as substance use, risky driving and speeding. Fewer had completed secondary school or undertaken further education. They were more often involved in antisocial peer friendships. The low risk antisocial sub-group continued to be very similar to the high risk antisocial group on these characteristics, but otherwise displayed a more limited, and generally less severe range of difficulties in early adulthood. Thus, there appeared to be few differences in the early adulthood outcomes of individuals traversing these differing pathways to persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour, regardless of the age of onset.

Motivations to comply with the law, attitudes, and antisocial behaviour

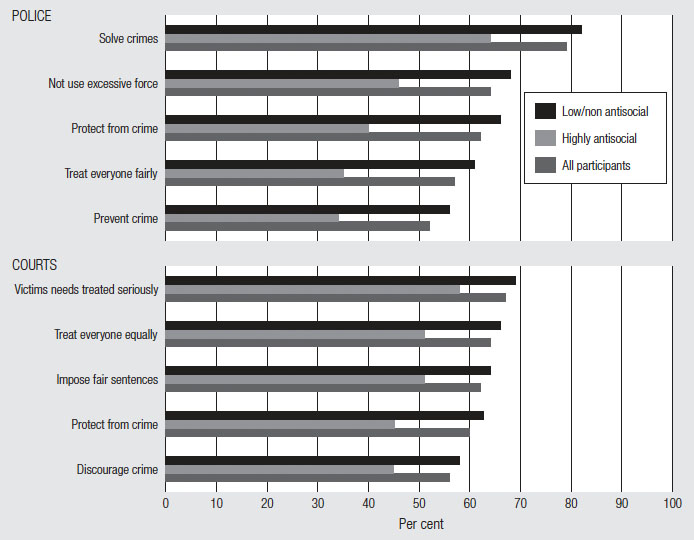

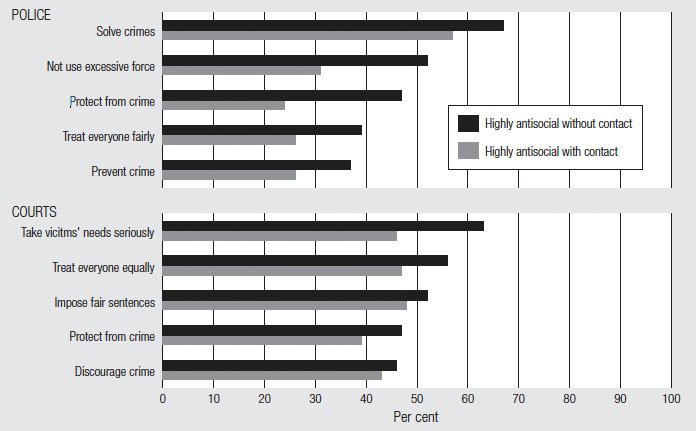

Connections between motivations to comply with the law, attitudes toward police and courts, and engagement in antisocial behaviour were explored. Two types of motivations were investigated: the perceived risk of apprehension if an offence is committed, and a sense of community attachment or civic mindedness. The attitudes towards police and courts of those who did, or did not, engage in antisocial behaviour were also examined.

Perceptions of the risk of apprehension were found to be inversely related to involvement in antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years of age. Only one of the three aspects of civic mindedness, trust in organisations, differentiated between highly antisocial and low/non antisocial young adults. Overall, perceptions of the risk of apprehension appeared to be a more important influence on engagement in antisocial behaviour than civic mindedness.

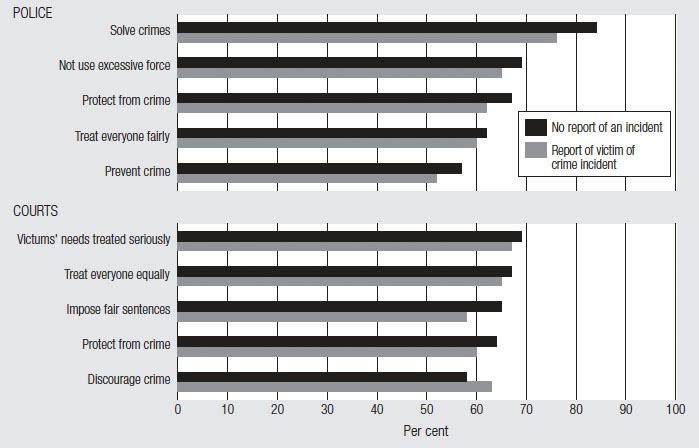

In general, most young adults held positive attitudes toward the police and courts. Across a range of aspects, an average 63 per cent of young people indicated that they had some or a great deal of confidence in the effectiveness of these agencies. Most low/non antisocial young people who had reported a victimisation incident to police expressed positive attitudes toward police and the courts, perhaps reflecting satisfaction with the way these agencies had attended to their needs. However those who were highly antisocial and/or had contact with police and courts for offending, were less positive in their attitudes towards the police and courts. A number of reasons for the lower confidence of these individuals were proposed, as were approaches for inhibiting the development of such attitudes.

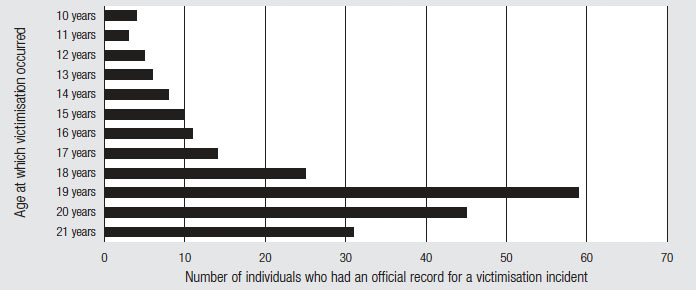

Official records and self-reports of offending and victimisation

The similarities and differences between self reports and the official records maintained by police were investigated. Official records and self reports were compared on criminal acts, contact with police and courts for offending, and contact with police regarding victimisation. The similarities and differences in the profiles of individuals identified by official records and self reports were also explored.

The analyses were restricted to the individuals who gave permission for access to official records (74 per cent). While there were no differences between those who consented and those who did not on family socio-economic background and community/local area characteristics, those who consented had less often engaged in antisocial behaviour and were less often males. However, a considerable number who did consent had engaged in antisocial behaviour and/ or self-reported contact with police or courts for offending.

The great majority of individuals who had an official record for offending also self reported engaging in the behaviour in question. Additionally, official records concerning victimisation incidents were matched quite closely by self reports, with almost four-fifths of individuals with a record for such an incident self reporting that they had contacted police regarding the incident. These findings suggest that self reports tend to be relatively accurate and reliable. However, when self reports were compared to official records, only a minority of those who self reported offending were found to have an official record. Among the reasons why self reported offending may not have been recorded are: the offence may not have taken place, the offence may not have been detected; there may have been insufficient evidence for further action, or the offence may have been dealt with unofficially. These findings are consistent with other research into this issue, and several explanations for the findings were offered. Agreement between self reports and official records was also relatively low for victimisation incidents.

The socio-demographic profiles of the group of offenders identified by official records was compared to the profile of the group of persistently antisocial adolescents identified by self reports and found to be similar. There were no significant differences on any aspect, including gender ratio, family socio-economic background; residence in a metropolitan, regional or rural location; and characteristics of the local area in which these young people lived (for example, unemployment rates, economic resources, crime rates). Thus, there was no evidence that the profile of offenders identified by official records was unrepresentative or atypical.

Implications

Reflecting on the findings from all three reports from this collaborative project, several important implications were highlighted. It is important to note that while occasional, limited engagement in antisocial behaviour was found to be relatively common, only a minority of young people (never more than 20 per cent) were involved in high levels, or persistent, antisocial behaviour at the separate time points. Nevertheless, the actual and psychological costs of antisocial behaviour to the individual, his/her family, community and society can be extensive.

The diversity of pathways to antisocial behaviour

A number of distinct pathways to antisocial behaviour commencing in early childhood, early adolescence and early adulthood were revealed. There appeared to be few differences in the later outcomes of individuals traversing these separate pathways, regardless of the age of onset. However, somewhat differing clusters of risk factors were identified for the differing pathways. The pathway commencing in early childhood was the most common. Fewer individuals followed the pathways that began in early adolescence and early adulthood. Considerable capacity for a change in pathways both in both childhood and adolescence was demonstrated. Several important transition points were identified that coincided with periods when major life changes were occurring. Key transition points at the entry to primary and secondary schooling may provide particularly promising opportunities for interventions, when children are especially amenable to change.

The co-occurrence of problem behaviours

Antisocial behaviour frequently co-occurred with other types of problem behaviours, such as substance use. One likely consequence of the overlap in problem behaviours is that strategies aimed at preventing the development of one type of problem behaviour may have a wide impact, preventing or ameliorating the development of other problem behaviours. However, there was considerable variability among young people who engaged in antisocial behaviour and not all highly antisocial young people displayed multiple problem behaviours. Differing intervention strategies may be needed to cater for multi-problem, and single-problem, youth.

Intervention implications

The findings are a reminder that to be "high risk" merely increases the likelihood but not the inevitability of a problematic outcome. Similarly, to be "low risk" decreases the likelihood of an adverse outcome, but is not a guarantee of a positive one. The environmental contexts in which children's development takes place, especially the family, peer and school contexts, were found to be powerful influences on the development of antisocial behaviour. For some children, these environments appeared to provide a buffering or protective influence which assisted them to move onto more positive developmental pathways. For others, less optimal environmental influences may have been instrumental in diverting them from a positive pathway. Overall, a mix of community- and school-based initiatives, together with more individualised approaches, may provide the most effective means of preventing or reducing the development of antisocial behaviour.

Summary

This Third Report marks the culmination of the very productive collaboration between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria. It is hoped that the findings contained in these three reports, which offer data from a unique study of Victorian children and families, will contribute to the evidence base to guide policy making and practical interventions aimed at preventing the development of antisocial behaviour in young Australians.

1. Introduction

This is the third and final report in the series Patterns and Precursors of Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour investigating the patterns and development of antisocial behaviour among a representative sample of Victoria adolescents. The Report is the product of the collaborative partnership between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria, which began in 2001 when Crime Prevention Victoria commissioned the Institute to collect and analyse Australian Temperament Project data concerning the development of antisocial behaviour in adolescence and early adulthood. The findings emerging from the project provide a valuable knowledge base which can inform and guide prevention and early intervention efforts.

The Australian Temperament Project (ATP) is a large, longitudinal study which has followed the development and adjustment of a community sample of Victorian children from infancy to young adulthood, with the aim of tracing the pathways to psychosocial adjustment and maladjustment across the children's lifespan (Prior, Sanson, Smart, and Oberklaid 2000). Upon recruitment, the sample consisted of 2443 infants (aged four to eight months) and their parents, who were representative of the Victorian population. Approximately two-thirds were still participating in the study in 2004. A total of 13 waves of data have been collected thus far, via annual or biennial mail surveys. Parents, teachers and the young people themselves have acted as informants at various stages during the project.

The First Report from this collaborative project, Patterns and precursors of adolescent antisocial behaviour (Vassallo, Smart, Sanson, Dussuyer, McKendry, Toumbourou, Prior and Oberklaid 2002), examined the nature and extent of antisocial behaviour among participating adolescents; identified different patterns of antisocial behaviour; and the precursors of this type of behaviour. In summary, antisocial behaviour was found to be quite common between the ages of 13 and 18 years. For example, at 13- 14 years, one in three adolescents had been involved in a physical fight in the past year, and at 17-18 years, over 40 per cent reported having skipped school at least once in the past year. Substance use (especially cigarette and alcohol use) was also relatively common, especially during mid to late adolescence.

A number of distinct patterns of antisocial behaviour were identified. These included a low/non antisocial pattern (little or no antisocial behaviour between the ages of 13 and 18 years, 73 per cent of adolescents), an experimental pattern (high levels of antisocial behaviour during early- to mid-adolescence only, 8 per cent of adolescents), and a persistent pattern (high levels of antisocial behaviour throughout adolescence, 11 per cent of adolescents). The low/non antisocial pattern was by far the most common, although close to 20 per of adolescents were found to have engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour at some stage.

The antecedents of persistent and experimental antisocial behaviour were investigated. Significant differences between the persistent antisocial group and the low/non antisocial group were evident from the early primary school years on, and increased in strength and diversity over time. A range of precursors of persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour was found. The most powerful precursors centred on intra-individual characteristics such as temperament, behaviour problems, social skills, levels of risk-taking behaviour and coping skills. Additionally, school adjustment and peer relationships, particularly antisocial peer friendships, emerged as important. Significant group differences in aspects of the family environment, such as the quality of the parent-child relationship and parental supervision of adolescents' activities, were also found. Risk factors for experimental adolescent antisocial behaviour were identifiable from the early secondary school years onwards, and were similar, but generally less powerful, than those identified for persistent antisocial behaviour.

The Second Report, Patterns and precursors of adolescent antisocial behaviour: Types, resiliency and environmental influences (Smart, Vassallo, Sanson, Richardson, Dussuyer, McKendry, Toumbourou, Prior and Oberklaid 2003), focused on four specific issues related to antisocial behaviour in adolescence and early adutlhood. These were: the precursors and pathways to violent and non-violent adolescent antisocial behaviour; resilience against the development of adolescent antisocial behaviour; connections between Local Government Area characteristics and adolescent antisocial behaviour; and patterns of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood (19-20 years).

Distinct developmental pathways and risks for violent and non-violent adolescent antisocial behaviour were found. Some risk factors were common to both types of antisocial behaviour, such as aggression, a less "persistent" temperament style (difficulties in persevering with tasks and activities), school adjustment difficulties, and lower social skills. Additionally, some risk factors applied particularly to violent antisocial adolescents, such as a more "reactive" temperament style (volatility, intensity, moodiness), higher sensation seeking, and greater difficulties in interpersonal relationships. The importance of distinguishing between subtypes of violent youth was also demonstrated, and the longstanding difficulties of the small sub-group who engaged in both violent and non-violent antisocial behaviour were highlighted.

The investigation of resilience revealed that a marked change in the developmental pathways of the "at risk" group who did not subsequently engage in adolescent antisocial behaviour took place over the early secondary school years. While equally as problematic during childhood as the "at risk" group who progressed to adolescent antisocial behaviour, the "resilient" subgroup was found to improve in many life domains. These included a decrease in aggressiveness, improvement in social skills, greater control of emotions, an "easier" temperament style than previously, improving relationships with parents, and greater school attachment and achievement. Additionally, the "resilient" sub-group had not developed friendships with other antisocial youth, and tended to receive better quality parenting (for example, closer supervision). Thus, a range of personal, environmental and situational factors appeared to be important in diverting "at risk" children from a problematic pathway.

Effects of local government area characteristics on involvement in adolescent antisocial behaviour were not found. Thus, rates of persistent, experimental and low/non antisocial behaviour were similar among adolescents living in disadvantaged areas (local government areas that were ranked among the most disadvantaged 20 per cent in the state on various characteristics) by comparison with those living in less disadvantaged areas. Rates of adolescent antisocial behaviour were similar across metropolitan, regional or rural locations. Additionally, living in a disadvantaged or high crime area did not appear to interact with characteristics of the peer and family environment (a non-intact family unit, low levels of parental supervision, or frequent association with antisocial peers) to increase the likelihood that an individual would engage in persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour. However, several methodological difficulties limited somewhat the study's ability to thoroughly investigate this issue

The investigation of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood found that such behaviour was relatively common, with 46 per cent reporting engagement in one or more type of antisocial acts during the past year. However, most young people were involved in a small number and range of antisocial acts. For most types of behaviour, very few engaged in the behaviour on more than one occasion. Overall, 15 per cent had engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour (defined as engagement in three of more different types of antisocial acts within the previous 12 months, a decrease from the rates of 20 per cent found at 15-16 and 17-18 years. The across-time trends revealed that rates of many types of antisocial behaviour continued to decline from a peak at mid adolescence, although substance use increased steadily until late adolescence and remained constant from that time.

Following on from these two reports, this Third Report investigates six further issues related to antisocial behaviour in adolescence and early adulthood. The first four sections explore pathways to and from antisocial behaviour, the fifth section examines connections between antisocial behaviour and young people's attitudes and values, and the sixth compares official records and self reports of antisocial behaviour. It is hoped that the findings will provide important information about the development of antisocial behaviour, as well as valuable new Victorian evidence to underpin early intervention and prevention efforts.

The issues investigated in the Third Report are:

- a. the continuity of antisocial behaviour into early adulthood;

- b. connections between antisocial behaviour and victimisation;

- c. the role of adolescent substance use in the development of adolescent antisocial behaviour;

- d. pathways to adolescent antisocial behaviour among low-risk children;

- e. relationships between motivations to comply with the law, attitudes, antisocial behaviour; and

- f. concordance between self reports and official records.

2. Transitions to early adulthood and the continuation, cessation and commencement of antisocial behaviour

The extensive body of research into adolescent antisocial behaviour reveals a complex picture. Not only have a wide range of risk factors been identified (Homel, Cashmore, Gilmore, Goodnow, Hayes, Lawrence, et al. 1999), but there appear to be differing developmental pathways into and out of such behaviour (Vassallo et al. 2002). The risk factors delineated include individual characteristics such as aggressiveness and a volatile temperament style; facets of the family environment such as lower supervision and punitive parenting; school environment factors such as lower attachment and academic difficulties; problematic peer relationships, particularly friendships with antisocial peers; and community and broader societal characteristics such as crime- and violence-prone neighbourhoods and cultural norms concerning violence and antisocial behaviour.

The differing developmental pathways identified include "life course persistent" and "adolescent limited" patterns of antisocial behaviour (Moffitt 1993), and the "overt", "covert" and "authority conflict" pathways described by Loeber and colleagues (Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber 1998). Similarly, the collaborative project between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria has identified persistent and experimental patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour, as well as the risk factors for and pathways to these types of behaviour (Vassallo et al. 2002).

There also appear to be a number of key transition points in the pathways to adolescent antisocial behaviour. The current series of studies has shown that the early primary school years (from five to eight years of age), and the transition from primary to secondary school (from 12 to 14 years), are particularly significant points of change in developmental pathways (Smart et al. 2003; Vassallo et al. 2002).

First, the pathway of the group who engaged in persistent antisocial behaviour in adolescence began to noticeably diverge from the group who were never involved in such behaviour in adolescence during the early primary school years, suggesting a critical junction at this age. Higher levels of aggression, hyperactivity, volatility and poorer capacities to stay on task were evident among the persistent adolescent antisocial group from the early primary school years onwards.

Second, a number of children whose individual characteristics and attributes suggested that they were "at risk" for the development of antisocial behaviour in adolescence, were found to improve markedly in many spheres of their lives in the early secondary school years and did not progress to persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour. Their pathways first noticeably diverged from the "at risk" sub-group who went on to engage in persistent antisocial behaviour during the early secondary school years, suggesting a second important turning point. It appears that these two time points are sensitive transition periods, or critical crossroads, during which individuals may be particularly amenable to change, when prevention and early intervention efforts may be especially effective.

While epidemiological studies show that a general drop-off in offending occurs in early adulthood, there has been less research into individual trends, such as the continuation of persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour into adulthood, and the long-term impact of differing types of adolescent antisocial behaviour on the opportunities, experiences and wellbeing of young adults. Furthermore, the early adult stage of development may provide a third important transition point during which pathways may again change.

These issues are taken up here. Three research questions are investigated. What is the continuation of antisocial behaviour into early adulthood? Does a change in developmental pathways occur during early adulthood? What are the adult outcomes of adolescents who displayed differing patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour?

An overview of research into the continuation of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to adulthood, and the impact of the transition to young adulthood on adjustment and wellbeing, is first presented.

Research into the continuation of antisocial behaviour into adulthood

Studies tracking trends over time show that the frequency of most types of antisocial behaviour declines from adolescence to early adulthood, particularly property and violent antisocial acts (Rutter, Giller and Hagell 1998). Rates of property offences tend to decline earlier than violent offences (Ross, Wlalker, Guarniere and Dussuyer 1994). However, the prevalence of substance use appears to increase across adolescence and peak in the twenties (Spooner, Hall and Lynskey 2001).

Within these broad trends, there are differing individual patterns of stability and change. Several longitudinal studies have investigated these individual patterns, focusing particularly on the continuation of persistent types of adolescent antisocial behaviour into adulthood (for example, Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington and Milne 2002). Some have focused on high-risk or socially disadvantaged samples (Farrington 1995), while others have involved representative community samples. Across both types of studies, considerable continuity of antisocial behaviour is evident among individuals who had engaged in persistent adolescent antisocial behaviour.

The influential Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development found substantial continuity of criminal behaviour from adolescence to adulthood among a sample of boys living in inner-city London (Farrington 1995). Almost three-quarters of young men who had received juvenile convictions were reconvicted between 17 and 24 years of age, and almost half were reconvicted between 25 and 32 years. The juvenile offenders who began offending early tended to become the most persistent offenders later on. Juvenile offenders also tended as adults to be involved in other problem behaviours, such as alcohol, cigarette and illicit drug use; gambling; and risky or drink driving.

By 32 years of age, a decrease in levels of antisocial behaviour had occurred across the sample, although those who were most problematic when younger continued to be the most problematic at this later age. As well as committing higher rates of offences, they were more likely to have mental health problems, employment difficulties, and be divorced or separated. Those with a history of persistent convictions were more problematic than "desisters" (those convicted only before 21 years or age) or "late-comers" (convicted after 21 years).

The study also examined the later life outcomes of a sub-group identified as being on an "adolescent-limited" pathway (this group exhibited problems for the first time in adolescence). While individuals in this group were not more prone to be convicted of an offence at 32 years, they continued to display a range of problem behaviours, including illicit drug use, heavy drinking, involvement in fights and criminal behaviour. However, their employment histories were similar to a non-antisocial sub-group, and their relationships with spouses were more positive than those of the group identified as "life-course persistent" (Nagin, Farrington and Moffitt 1995).

Similarly, the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Study of Health and Development has reported that adolescent boys identified as being on a life-course persistent pathway of antisocial behaviour had the highest rates of difficulties on a range of outcomes at 26 years of age (Moffitt et al. 2002). They had the highest rates of drug-related and violent crime, psychopathic personality traits, substance dependence, mental-health problems, and work and financial difficulties. Boys identified as progressing along an "adolescent-limited" pathway were also problematic at 26 years, although less severely than the "life course" persistent group. These young men tended to have elevated rates of property offences, as well as an impulsive personality style, mental-health problems, substance dependence, and financial difficulties.

Other factors found to be associated with the continuation of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to adulthood include lower intelligence, poorer scholastic achievement, more pathological personality characteristics, higher rates of substance abuse, and an earlier start on an antisocial pathway, according to the review by Elkins and colleagues (1997). As well, continuity of adolescent antisocial behaviour appears to be higher among males than females (Storvall and Wichstrom 2003). The Seattle Social Development Study has shown that the continuation of violence from adolescence to adulthood was most powerfully predicted by male gender and friends' antisocial behaviour, with scholastic achievement exerting a protective effect against the persistence of violence (Kosterman, Graham, Hawkins, Catalano and Herrenkoh 2001). Adolescent alcohol use was found to be highly predictive of the continuation of criminal behaviour into adulthood among a Swedish cohort (Andersson, Mahoney, Wennberg, Kuehlhorn and Magnusson 1999).

In summary, in spite of the general decrease in antisocial behaviour that occurs in early adulthood, there appears to be considerable continuity of antisocial behaviour for particular sub-groups, especially those on persistent or "life-course" pathways. Factors found to increase continuity include male gender, personality traits, school difficulties, substance use, lower intelligence, friendships with antisocial peers, and an earlier onset of adolescent antisocial behaviour. However, the continuation of such behaviour into adulthood is not a 'fait accompli', with a number of individuals observed to desist. As well as the factors listed above, it is possible that the experiences and opportunities encountered in the early adult developmental period play a pivotal role in whether a continuation of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to adulthood occurs.

The transition to early adulthood

What features of early adulthood may make it a critical transition point? This period tends to be a time of considerable change, marked by major life transitions such as increasing psychological and social independence, the completion of secondary schooling, the commencement of higher education and/or employment, and the development of intimate relationships (Arnett 2000). At the same time, however, this stage is often nowadays one of prolonged financial and material dependence, with many young people studying longer, taking up employment, establishing careers and marrying later than in previous generations (Arnett 2000; Coles 1996).

The early adult years may also provide new opportunities and pressures. On one hand, some young people may be able to leave behind a difficult or troubled adolescence and find a new start and fulfillment in adult life through the development of a satisfying career (Horney, Osgood and Marshall 1995; Sampson and Laub 1993). The forming of romantic relationships may also provide a beneficial influence and facilitate positive change. For example, the development of a stable intimate relationship appeared to inhibit engagement in antisocial activities among young men who had previously been prone to such behaviour (Quinton, Pickles, Maughan and Rutter 1993). Similarly, Lackey (2003) highlighted the importance of a commitment to an intimate partnership and to employment in assisting young men to desist from violent behaviour. These findings are important for crime prevention as they point to the possibility of a change in pathways at this time.

On the other hand, the transition may be a difficult or challenging experience. Employment and career opportunities may be scarce, or the educational choices taken may be ill-suited, leading to an unsettled period. For example, a negative start in the transition from school to work may be a forerunner of longer-term difficulties (Lamb and McKenzie 2001). Intimate relationship difficulties and breakdown during early adulthood may be a considerable source of unhappiness (Larson, Wilson, Bradford Brown, Furstenberg and Verma 2002). Thus, while the transition to young adulthood can be associated with increased personal happiness and wellbeing for many young people, the life paths traversed at this time can also negatively affect adjustment and life satisfaction (Schulenberg, O'Malley, Bachman and Johnston 2000).

An extension of the peak age of offending from mid-adolescence into late adolescence and young adulthood has recently been observed, particularly among young men (Rutter, Giller and Hagell 1998). It has been suggested that the trend for an extended period of dependence may play a role in prolonging young people's engagement in antisocial and criminal behaviour (Moffitt et al. 2002).

There is also some evidence for the emergence of a late onset antisocial group during early adulthood. Moffitt and colleagues (2002) identified a group who had been aggressive in childhood but who were not antisocial in adolescence, yet who, by 26 years of age, were chronic low-level offenders. They also tended to be more anxious, depressed and isolated, and had experienced more financial and employment difficulties. Similarly, a small group of adult violent offenders who did not have an earlier history of aggression were identified by two other longitudinal studies (Farrington 1994; Magnusson, Stattin and Duner 1983). The review conducted by Elkins et al. (1997) concluded that the late onset offending group displays a similar profile of problems in adulthood as the life-course persistent group, and therefore may warrant particular attention.

In summary, the early adult years appear to be another key transition period in which a change in pathways may occur. For some, a cessation of antisocial and criminal behaviour takes place, while for others there is an onset of such behaviour for the first time. It is possible that the changes in pathways are influenced by the ease with which this transition period is negotiated.

Methodology

The collaboration between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria provides an opportunity to explore a number of issues related to the continuity of antisocial behaviour from adolescence into early adulthood, and to explore the early adult outcomes of young people who display differing types of adolescent antisocial behaviour.

The following questions are investigated: What is the continuity of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to early adulthood? Can a late onset group be identified, and if so, what are the correlates of this type of behaviour? Are transition experiences related to the onset of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood? What are the life circumstances and wellbeing of young people with differing patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour?

Participants

A detailed description of the methods used to recruit the sample, and the measures used over the first 12 survey waves, has previously been provided (see First Report from this collaborative project,Vassallo et al. 2002; also Prior, Sanson, Smart and Oberklaid 2000).

In brief, the Australian Temperament Project (ATP) cohort of 2443 infants and families, selected to be representative of urban and rural areas of the state of Victoria, Australia, was recruited in 1983. Thirteen waves of data have been collected by mail surveys from infancy to 19-20 years. Parents, Maternal and Child Health nurses, teachers, and the children themselves have completed questionnaires assessing adjustment and development over major domains of functioning.

Approximately two-thirds of the cohort is still participating after 20 years. A higher proportion of the families who are no longer participating are from a lower socio-demographic background or include parents who were not born in Australia. Importantly however, the retained sample closely resembles the original sample on all facets of infant functioning, with no significant differences between the retained and no-longer-participating sub-samples on any infancy characteristics (for example, temperament style, behaviour problems). Hence, while the study continues to include young people with a broad range of attributes, it contains fewer families experiencing socio-economic disadvantage than at its commencement (although it still contains families living in diverse circumstances).

The data used come from 1140 young people (505 males, 635 females) who completed questionnaires during the thirteenth data collection wave at 19-20 years of age (in 2002). Parallel parent reports were also available for many of the facets of functioning assessed.

Measures

Adolescent antisocial behaviour measure

Data from the three survey waves from 13 to 18 years were used to identify differing across-time patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour. The methods used are described in full in Vassallo et al. (2002), and will only be briefly described here.

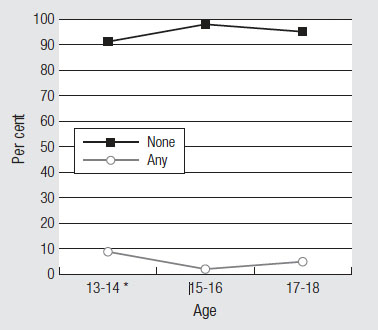

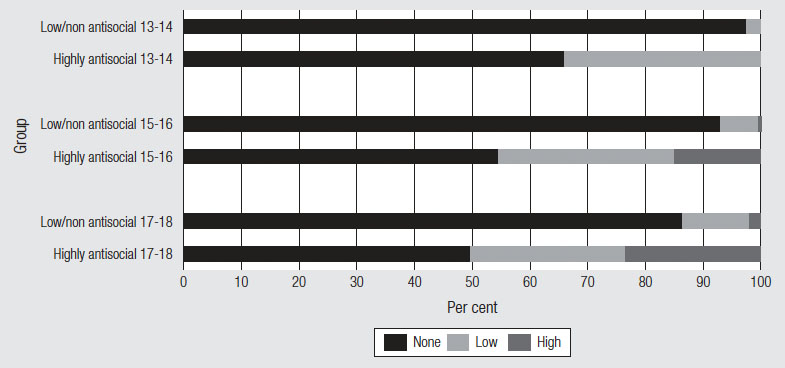

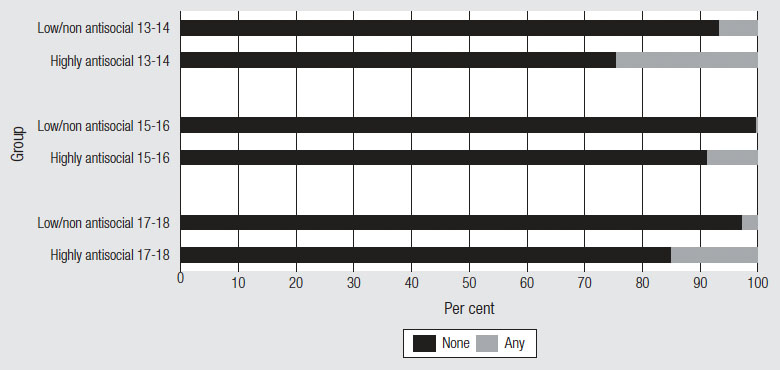

First, individuals were classified as displaying high or low levels of antisocial behaviour at each time point (at 13-14, 15-16 or 17-18 years). Thus, adolescents who reported engaging in three or more different types of antisocial acts during the previous 12 months were classified as highly antisocial at that particular time point. Those who reported fewer than three different antisocial acts during the previous 12 months were classified as low/non antisocial at that time point.

Second, the classifications at the three time points were used to identify differing, across-time patterns of antisocial behaviour. While a number of trajectories were found, three main groups were identified. These were:

- 844 low/non antisocial individuals, 41 per cent male (these adolescents exhibited no or low levels of antisocial behaviour at all three time points);

- 88 experimental individuals, 43 per cent male (these adolescents exhibited high antisocial behaviour at only one timepoint during early-to-mid adolescence and then desisted); and

- 131 persistent individuals, 65 per cent male (these adolescents reported high antisocial behaviour at two or more timepoints, including the latest timepoint of 17-18 years).

The low/non antisocial trajectory was the most common, with 73 per cent of adolescents on this pathway; 11 per cent of adolescents appeared to be on a persistently antisocial pathway; and a further 8 per cent on an experimental pathway.

Early adulthood antisocial behaviour measure

The same strategy was used to identify young people who engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years. Thus, those who had been involved in three or more different types of the antisocial acts1 listed in Table 1 during the past 12 months were categorised as highly antisocial, while those who were involved in fewer than three different types of such acts were categorised as low/non antisocial. A total of 177 individuals, 15.5 per cent of respondents (67 per cent of whom were male), were found to engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years.

| Items used to assess antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years (2002) |

|---|

|

| # New items added for this data collection wave * These items relate to the past month; all other items refer to the past year |

Other measures at 19-20 years

The 19-20 years of age data set collected in 2002 contains a broad array of measures, covering many aspects of the young adult respondents' lives. These were grouped into four broad domains2 – life circumstances, individual attributes, adjustment, and interpersonal and community relationships. A brief description of the measures is provided here. For further details of the measures used, refer to Appendix 1. Most measures came from self-report, with parent report also available for many of the aspects assessed.

Life circumstances

- Vocational and educational circumstances – currently in employment, currently undertaking a tertiary or further education course, current occupation (self report).

- Educational history – completed secondary schooling, Tertiary Entrance score obtained, undertaken multiple tertiary courses since leaving school (self report).

- Employment history – pattern of employment since leaving school (generally employed or periods of seeking employment) (self report).

- Living arrangements – with parents or away from home (self report).

- Financial circumstances – sources of income (paid employment, parental support, government assistance), average weekly income, financial strain (self report); parental assistance via payment of education fees, helping with bills or rent, providing a regular allowance, giving or loaning money, or other material support (parental report).

- Family environment – family socio-economic background, family experience of financial strain; parental unemployment (parental report)

Individual attributes

- Temperament style – approach-sociability, flexibility (for example, how adaptable she/he is), positive emotionality (for example, cheerfulness or happy mood), negative reactivity (for example, volatility or negativity), persistence (capacity to see things through to completion), distractibility (how easily distracted), activity (for example, energetic, on the go) (self and parental report).

- Social competence – empathy, responsibility, self control, assertiveness (self and parental report).

- Religious faith (self report).

- Emotional control – for example, ability to remain positive in difficult situations; management of emotions – for example, difficulty in controlling emotions (self and parental report).

Adjustment

- Depression – (Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Lovibond and Lovibond 1995) (self report).

- Stress – (Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Lovibond and Lovibond 1995) (self report).

- Anxiety – (Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Lovibond and Lovibond 1995) (self report); anxiety-withdrawal – for example, is anxious, fearful; is depressed, sad (short form of Revised Behaviour Problem Checklist, Quay and Peterson 1987) (parental report).

- Socialised aggression – for example, admires people who act outside the law (short form of Revised Behaviour Problem Checklist, Quay and Peterson 1987) (parental report).

- Conduct disorder – for example, deliberately cruel to others; bullies or threatens others (short form of Revised Behaviour Problem Checklist, Quay and Peterson 1987) (parental report).

- Alcohol and cigarette use – in past month, deleterious effects of alcohol use, binge drinking (self report).

- Risky driving – speeding, driving when tired, drink driving, driving when affected by drugs, failure to wear seatbelt: averaged to form a composite risky driving score; number of times apprehended for speeding; number of motor vehicle crashes experienced (self report).

- Experience of victimisation – been physically attacked or threatened; experienced home burglary; had motor vehicle stolen; had other items stolen (self report).

- Life satisfaction – degree of satisfaction with employment/education situation, personal appearance, interpersonal relationships, standard of living, accomplishments, direction life is taking – averaged to form a composite life satisfaction score (self report).

- Long-term physical or mental health problem (parental report of young adult problem).

Interpersonal relationships and community involvement

- Relationships with parents and friends – parents' emotional support (for example, they understand young adult), informational support (for example, give guidance and support), instrumental support (for example, give practical help); parents' negative appraisal (for example, critical of young adult); conflict with parents; friends' emotional, informational, instrumental support; friends' negative appraisal (parallel items to those used to measure parental support); (MacDonald 1998) (self and parental report).

- Size of friendship network (self report).

- Antisocial peer friendships – for example, friends drink heavily, use drugs, break the law (self and parental report).

- Involvement in a romantic relationship (self report).

- Romantic partner's antisocial behaviour – for example, partner drinks heavily, uses drugs, breaks the law (self report).

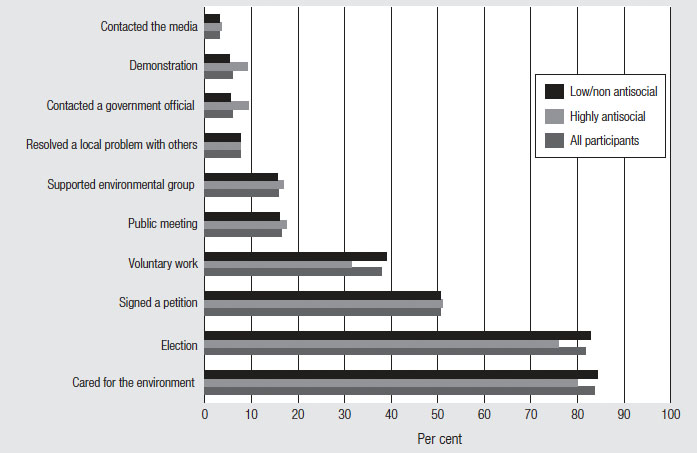

- Civic participation – undertaken voluntary work, undertaken environmentally-oriented activities, acted to solve a local or neighbourhood problem, contacted media or government regarding a problem, voted in election, attended a public meeting: averaged to form a composite score (self and parental report).

- Trust in organisations – confidence in the fair or reasonable conduct of the media, governments, public service, local councils, business organisations, trade unions, religious organisations: averaged to form a composite score (self report).

- Beliefs about the likelihood that a person would be apprehended for offending – for example, for shoplifting, theft, assault, fraud, drink-driving, marijuana use, or drug trafficking: averaged to form a composite score (self report).

- Perceptions of the fairness of police and courts – attitudes regarding the ability of police and courts to protect society from crime; treat people fairly; discourage, prevent or solve crimes; refrain from using excessive force; and take victims' needs seriously: averaged to form a composite score (self report).

Findings

In the following sections, findings are presented concerning, first, the continuation of antisocial behaviour into early adulthood, second, the onset for the first time of antisocial behaviour in late adolescence/young adulthood and the factors that might be related to the late onset of such behaviour, and, third, the early adult outcomes of groups with differing patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour.

Continuity of adolescent antisocial behaviour in early adulthood

Rates of antisocial acts among Australian Temperament Project participants over the period from early adolescence to young adulthood have previously been reported (Smart et al. 2003). In brief, the frequency of most property and violent antisocial acts continued to fall from a peak at mid adolescence. The selling of illicit drugs, shoplifting and substance use at 19-20 years are exceptions and continued at similar levels to those found at 17-18 years.

Regarding levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years among young people who had engaged in persistent, experimental or low/non antisocial behaviour from early to late adolescence, the persistent antisocial group was found to engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years (three or more different types of antisocial acts in the past 12 months) significantly more often than the experimental and low/non antisocial groups. 3 High levels of antisocial behaviour were displayed by 55 per cent of the persistent antisocial group, while 14 per cent of the experimental and 7 per cent of the low/non antisocial groups were also found to engage in high levels of such behaviour at 19-20 years.4

Were particular factors associated with the continuation or cessation of antisocial behaviour among the persistent adolescent antisocial group? To investigate this question, the persistent adolescent antisocial group was divided into two sub-groups: one who maintained high levels of antisocial behaviour (N=57), and one who did not engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years (N=47). These two sub-groups were compared on the four broad domains of functioning – life circumstances, individual attributes, adjustment, and interpersonal/community relationships.5. Somewhat surprisingly, these multivariate analyses did not reveal any significant differences between the two sub-groups overall.6

To explore this issue further, the degree of engagement in antisocial behaviour among the persistent adolescent antisocial sub-group who did not engage in high levels of such behaviour at 19-20 years was investigated. Interestingly, three-quarters had been involved in some antisocial behaviour in the past year, with 38 per cent having committed two different types of antisocial acts and 36 per cent reporting engagement in one antisocial act. Thus, only a minority, approximately one-quarter, may have entirely desisted at this stage.

Could a late-onset group be identified?

As noted earlier, 48 low/non antisocial group individuals (that is, who were never highly antisocial from 13 to 18 years) were found to have engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years. As well, as described in the First Report from this collaborative project (Vassallo et al. 2002), a small sub-group of adolescents was found who had not engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour in early or mid adolescence, but had displayed such behaviour in late adolescence which continued into young adulthood, (N=20). These two sub-groups were combined and classified as displaying a late-onset pattern of antisocial behaviour. (N=68, 69 per cent male).

In summary, while the majority of individuals who had displayed persistent antisocial behaviour across adolescence continued to engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years (55 per cent), a sizeable minority did not (45 per cent). (High levels of antisocial behaviour were defined as involvement in three or more different antisocial acts within the previous 12 months). Additionally, 14 per cent of those displaying experimental adolescent antisocial behaviour and 7 per cent of those with low/non antisocial behaviour from 13 to 18 years engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood.

Persistent group individuals who maintained high levels of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood were compared to their counterparts who had not engaged in high levels of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood, to investigate the factors that might have led to a change in behaviour. However, no significant multivariate differences were found. Looking more closely at the sub-group of persistent antisocial individuals who did not engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood, there were some signs of antisocial behaviour for the majority (although they did not meet the criteria developed of three or more different antisocial acts during the previous 12 months). Thus most reported engaging in one or two different types of antisocial acts and only one quarter appeared to have entirely desisted from antisocial behaviour at this age.

A sub-group of individuals was identified who, for the first time, reported high levels of antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years (N=48). Additionally, another 20 individuals had engaged in high levels of such behaviour at 17-18 and 19-20 years, but not in earlier adolescence. Thus, it seemed that the pathways of these two sub-groups appeared to change in early adulthood, and these individuals were categorised as displaying a late onset pattern of antisocial behaviour.

Outcomes of adolescents who displayed differing patterns of antisocial behaviour

The young adult outcomes of groups who displayed differing patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour are next reported. These analyses aimed to investigate the long-term impact of adolescent antisocial behaviour on later functioning and wellbeing. As well, these analyses explore the factors which might be associated with the commencement of antisocial behaviour in late adolescence or in early adulthood among the late-onset group. The persistent, experimental, low/non7 adolescent antisocial groups and the late-onset group were compared on their life circumstances, individual attributes, adjustment, and interpersonal/community relationships at 19-20 years.8 The groups comprised 104 persistent, 76 experimental, 68 late onset and 717 low/non antisocial individuals.

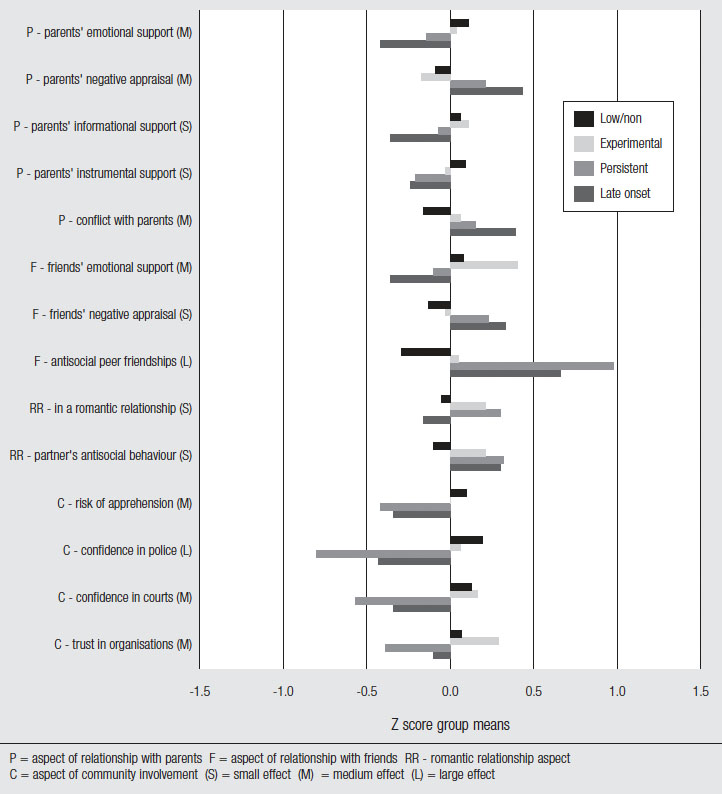

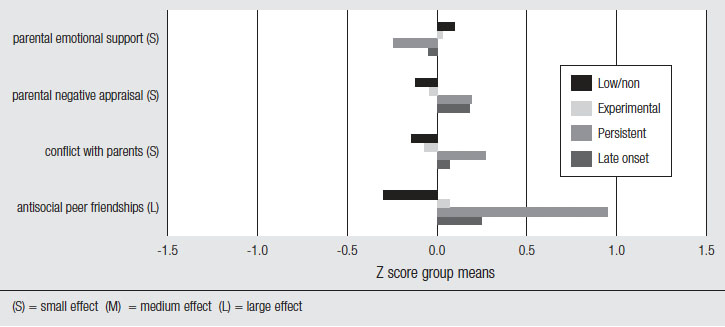

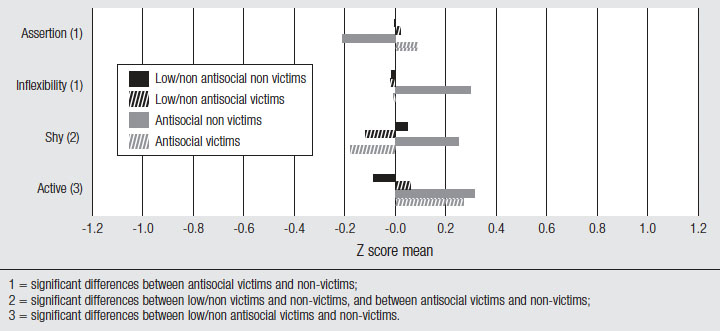

Aspects on which significant group differences were found are shown in Figures 1 to 7, while a summary of the findings is provided in Appendix 2. The Figures display the mean standardised scores9 (z scores) of the four groups on the variables for which significant group differences were found. Effect sizes were used to assess the strength of group differences across the various domains, and are included in the Figures10. For ease of interpretation, variables which were measures of the same domain of functioning are grouped together (for example, positive emotionality, persistence and activity – all of which are measures of temperament style - are grouped together in Figure 2).

Group differences on life circumstances

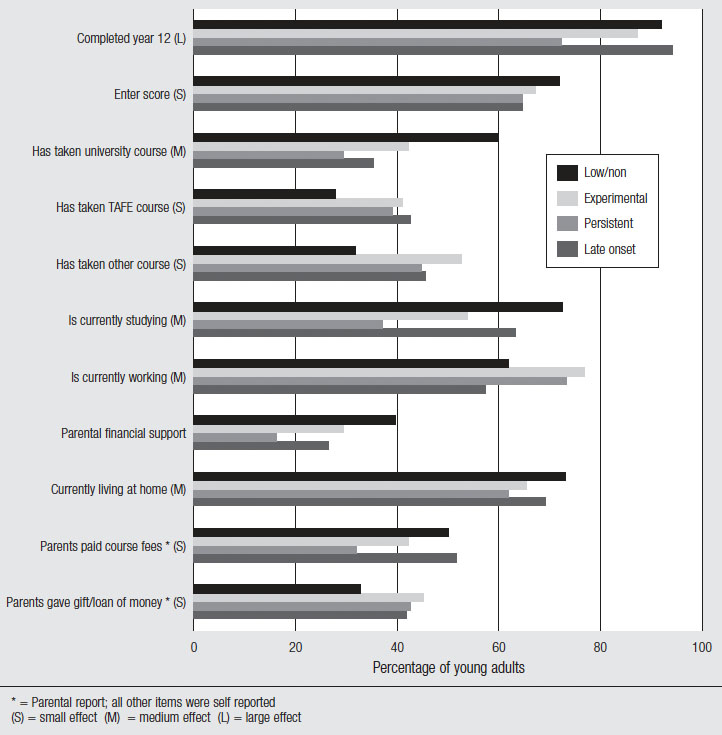

In general, the persistent antisocial group tended to be faring significantly less well than the other three groups (low/non, experimental and late-onset) on most facets of life circumstances measured, as shown in Figure 1. Most differences were between the persistent and low/non antisocial groups, but there were several aspects on which the persistent group was significantly different to all three other groups.

Aspects that particularly characterised persistent antisocial individuals were: fewer had completed secondary school, or were currently undertaking further study. Since leaving school, fewer had taken a university course of study, although they had undertaken other types of courses (for example, TAFE, other institutions or agencies). They tended to have higher incomes (perhaps because more were in full-time employment); but received less financial support from parents. Fewer were living at home. Turning now to the late-onset group, while they had high rates of secondary school completion and were currently undertaking further study, they were significantly less likely to have undertaken a university course of study, and, as Figure 1 shows, their tertiary entrance (Enter) scores were lower than the low/non and experimental groups. There was only one significant difference between the low/non and experimental groups, with the experimental group reporting higher rates of further study via private agencies, on the job training, Centrelink or similar agencies.

Figure 1. Comparison of the low/non, experimental, persistent and late onset groups on life circumstances

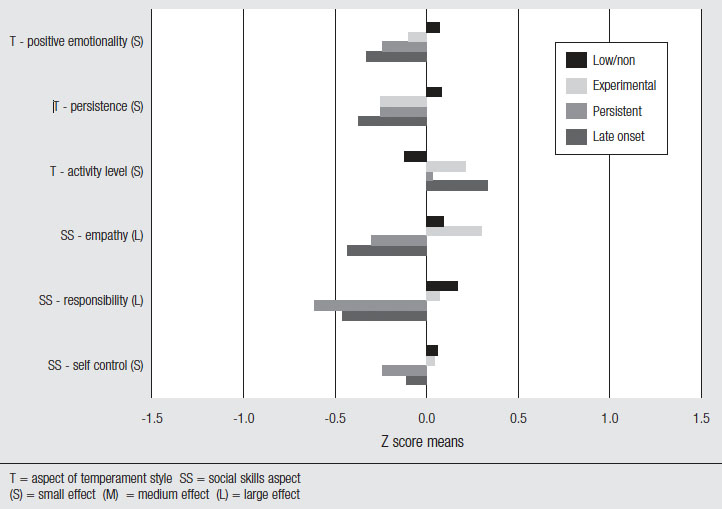

Group differences on individual attributes

Parents and young adults provided a very consistent picture of the four groups' individual attributes and capacities, as can be seen from Figures 2 and 3. Both concurred in rating persistent and late onset group individuals as having lower social skills, with powerful group differences particularly evident on empathic capacities and willingness to act responsibly (large effect sizes11). In addition, persistent group individuals had significantly poorer self control by their own and parental ratings, and had greater difficulty in managing and controlling their emotions according to parents.

Likewise, the persistent and late onset groups tended to display more "difficult" temperament characteristics, although these group differences were less powerful, with most in the small effect size range. Thus, both groups tended to be typically less cheerful and happy, the persistent group was less able to stay on task and see activities through to completion, as well as being more volatile and moody, while the late onset group was perceived to be more active and fidgety. The experimental group closely resembled the low/non antisocial group on most individual attributes, although it was significantly higher on the activity temperament dimension. Interestingly, experimental group individuals tended to possess higher levels of empathy than low/non antisocial group individuals, according to both parental and self reports.

Figure 2. Comparison of the low/non, experimental, persistent and late onset groups on self-reported individual attributes at 19-20 years

Figure 3. Comparison of the low/non, experimental, persistent and late onset groups on parent-reported individual attributes at 19-20 years

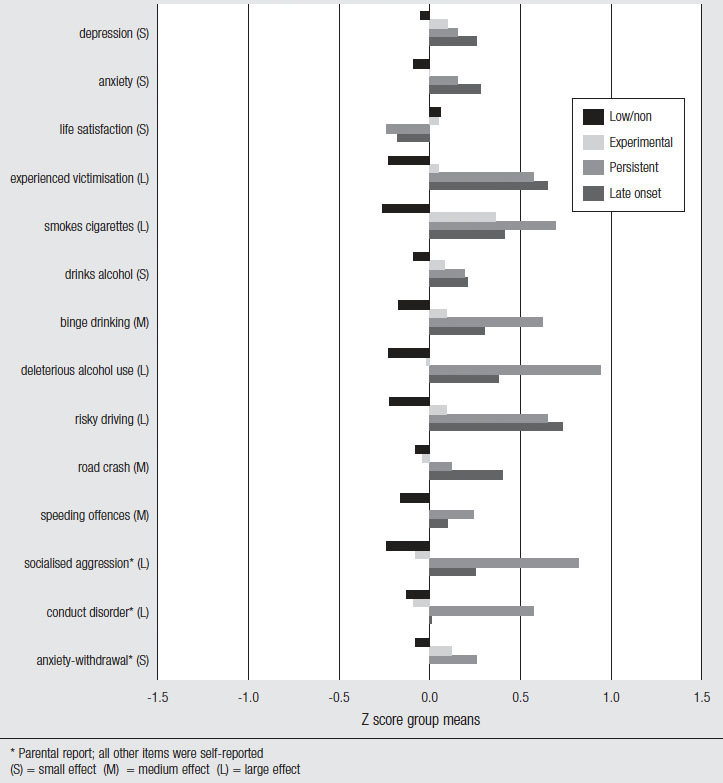

Group differences on adjustment

There were many significant differences between the persistent and late onset groups, on the one hand, and the low/non and experimental groups on the other, on the aspects of adjustment assessed (Figure 4). Aspects that particularly characterised both persistent and late onset group individuals were: binge drinking, harmful effects of alcohol use, having been a victim of crime, and a risky driving style. Group differences tended to quite powerful on most aspects, as evidenced by medium or large effect sizes.

The persistent group was notably more aggressive according to parental report, and reported they had more frequently been apprehended for speeding. The late-onset group had more frequently been involved in a road crash and were somewhat more anxious and depressed by their own self report. Both groups, as well as the experimental group, more frequently used cigarettes than the low/non antisocial group. On all other aspects there were no significant differences between the experimental and low/non groups.

Figure 4. Comparison of the low/non, experimental, persistent and late onset groups on self-reported and parent-reported adjustment at 19-20 years

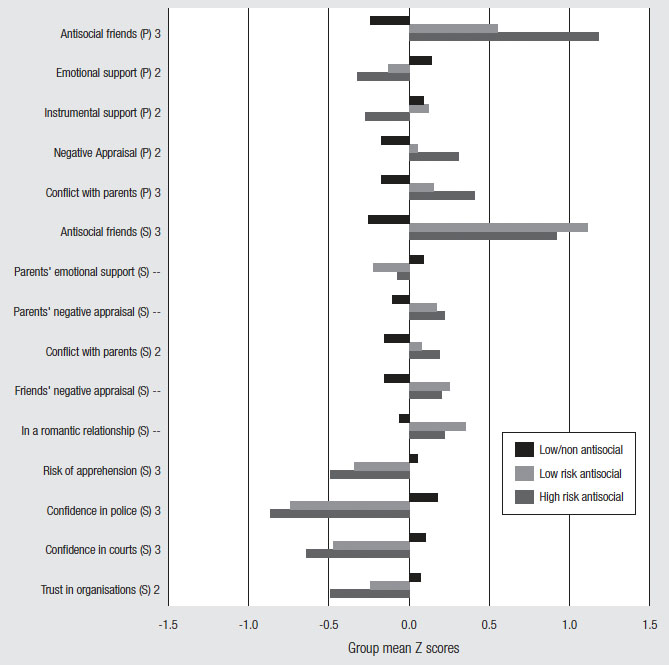

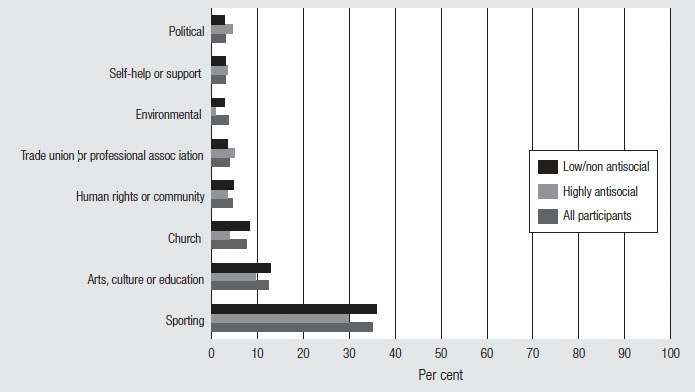

Group differences on interpersonal relationships and community involvement

The persistent and late onset groups were found to have poorer interpersonal relationships and less positive attitudes towards police, courts and other social organisations than the low/non and experimental groups, as shown in Figures 5 and 6. Notably, the late onset group had the most problematic relationships with parents and friends, feeling that they received less support and that parents and friends viewed them more negatively. Additionally, the persistent and late onset groups reported more conflict with parents than the low/non and experimental groups.

The persistent group had notably higher rates of friendships with other antisocial youth according to parents and their own reports (this was also apparent for the late onset group), and were more often involved in romantic relationships with partners who also tended to engage in antisocial behaviour. Both the persistent and late onset groups expressed much lower confidence in the competence of police and courts, with the persistent group also feeling less trust in other types of social organisations (for example, governments, media, trade unions). Both groups also estimated the likelihood of apprehension for a criminal offence would be considerably lower than did the low/non and experimental groups. The group differences on these aspects were all relatively powerful, being in the medium or large effect size range.

The only significant difference found between the experimental and low/non groups was on the experimental group's greater propensity to have antisocial friends (by both parental and self report), although it should be noted that rates of such friendships were still quite low. Interestingly, the experimental group displayed the highest trust in organisations and confidence in the courts by comparison with the other three groups.

Figure 5. Comparison of the low/non, experimental, persistent and late onset groups on self-reported interpersonal and community relationships / attitudes at 19-20 years

Figure 6. Comparison of the low/non, experimental, persistent and late onset groups on parent-reported interpersonal relationships at 19-20 years

In summary, the persistent, experimental, low/non adolescent antisocial groups, and the late onset group, were compared, with the aim of investigating the long-term impact of adolescent antisocial behaviour on later functioning and wellbeing, and the factors which could have contributed to a change in the pathway of the late onset group. Four broad domains of functioning were investigated: life circumstances, individual attributes, adjustment, and interpersonal relationships/community involvement.

Overall, the persistent and late onset groups appeared to be experiencing more difficulties than the experimental and low/non groups, while the experimental group closely resembled the low/non group.

The persistent group was found to be faring significantly less well than the other three groups on most facets of life circumstances. Fewer had completed secondary school and were currently undertaking further study; they tended to have higher incomes but received less financial support from parents and fewer were living at home. While the lateonset group had high rates of secondary school completion, they had obtained lower tertiary entrance (Enter) scores than the low/non and experimental groups and were significantly less likely to have undertaken university study.

In terms of individual attributes, both the persistent and late onset groups were found to be less socially skilled than the experimental and low/non groups, according to their own and their parents' reports. In particular, their empathic capacities and willingness to act responsibly were less well developed. They also tended to display more "difficult" temperament characteristics, such as being less cheerful and happy, more volatile, less capable of seeing tasks through to completion, and more active and fidgety.

There were powerful differences between the persistent and late onset groups on the one hand, and the experimental and low/non antisocial groups on the other, on most aspects of adjustment. These differences encompassed alcohol and cigarette use, binge drinking and harmful effects of alcohol use, a risky driving style and involvement in road crashes, as well as being a victim of crime. Parents also rated persistent group individuals as being considerably more aggressive.

On interpersonal relationships and community involvement too, the persistent and late onset groups were significantly more problematic than the experimental and low/non groups. Notably, the late onset group tended to have the poorest relationships with parents and friends, while the persistent group had much higher rates of friendships with other antisocial youth. Antisocial peer friendships were also more common among the late onset and experimental groups than the low/non group. Both the persistent and late onset groups held more negative attitudes towards the police and courts, and believed there would be less chance of apprehension if criminal offences were committed.

Discussion and implications

This first section of the Third Report investigated three issues regarding the course and consequences of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to early adulthood:

- What is the continuity of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to early adulthood?

- Can a late onset group be identified, and if so, what are the correlates of this type of behaviour? Are transition experiences related to the onset of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood?

- What are the adult outcomes of adolescents who exhibited differing patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour?

Conclusions and implications that may be drawn from the findings are now presented.

There was moderate continuity of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to early adulthood

Consistent with other studies, an overall decline in rates of antisocial behaviour from adolescence to early adulthood was found among this sample of young Victorians. This was particularly evident for most property and violent acts; however substance use, the selling of illegal drugs, and shoplifting remained stable from late adolescence to early adulthood. These findings confirm the normative trend reported elsewhere for antisocial behaviour to increase during early adolescence, peak at mid adolescence and then gradually decline (Baker 1998; Ross et al. 1994).

Three groups with differing across-time patterns of adolescent antisocial behaviour were followed forward in time to investigate their involvement in antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years. Moderate stability was found among those who had been persistently antisocial, with a majority (55 per cent) continuing to engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour in early adulthood. However, a sizeable minority of 45 per cent did not. Most of those who had engaged in antisocial behaviour only during early adolescence and desisted, or had never been involved in such behaviour in the adolescent years, did not engage in antisocial behaviour at 19-20 years.