Reconceptualising Australian housing careers

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

April 1999

Download Research report

Overview

Contemporary social theorists argue that advanced western societies are undergoing a remarkable and dramatic period of change – industrial society is said to be giving way to risk society. ‘Manufactured uncertainty’ and ‘individualisation’ are said to be the hallmark characteristics of this emergent risk society. In the face of these striking theoretical assertions, this paper explores empirically how the change to a risk society might be manifest in family life courses and, more particularly, housing careers. A cohort analysis of Australian Institute of Family Studies and Australian National University data seeks evidence of ‘differentiation’ and ‘disconnectedness’ in housing careers. Cohort differences in leaving the parental home, returns to the parental home, entering home purchase, and the sequencing of housing career and other life course events are examined as a means of assessing the extent to which Australian housing careers need to be reconceptualised in the transformation to a risk society.

The housing career, as well as the employment career, the marital career and the fertility career comprise the core elements of the contemporary family life course. A housing career refers to the path taken by a household in attempting to meet its housing choices and needs over a lifetime (Maher and Burke 1991:195).

In the past, the housing careers of Australian families have been characterised by high degrees of certainty and predictability, with strong links between particular phases of the life course and particular housing consumption outcomes. Through the economic certainty and stability of the 1950s and 1960s, the link between life course stage and housing moves became well established. A series of typical cultural practices in relation to housing consumption were mapped out. Young, single, adulthood was associated with entry to private renting, typically in inner-city locations. Partnering and child bearing were linked with entry to home ownership in outer suburban locations. Families then remained in the ‘family home’ until the death of a spouse or ill health in old age forced a move to serviced accommodation, either formal or informal.

With entry to home ownership the benchmark of Australian housing careers, Australian cultural identity has become closely intertwined with the Great Australian Dream. Home ownership has been one of the key means of providing certainty across the life course: the security and stability provided by home ownership connects it strongly with the phase of family formation, including partnering and birth of a first child; the long-term economic advantages of home ownership contribute to financial certainty through low housing costs in retirement; and intergenerational family continuity is provided for through inheritance of the family home.

Today, however, the certainty of the links between home ownership, Australian cultural identity, and the traditional family life course are being challenged. Increasing divorce and falling marriage rates, decreasing fertility rates, and the proliferation of other family and household forms such as one-parent families, and group and living alone households all contribute to a redefinition of contemporary life courses.

Home ownership is changing as well. Since 1981 the home ownership rate has fallen from 70 per cent to 66 per cent of dwellings, the lowest figure since 1954 (Winter and Stone 1998: 16). Home ownership affordability declined rapidly in the late 1980s to be replaced by a significant easing in the late 1990s. Government policies that assisted entry to home ownership in the 1970s and 1980s have now largely been removed. This is the immediate context of change that demands we rethink precisely how housing careers are unfolding in contemporary Australia – and that poses a challenge to the conceptual underpinnings of life course analyses.

The aim of this paper, therefore, is to reconceptualise the Australian housing career by drawing upon a theoretical framework of contemporary social change – risk society theory – to interpret the altered life course and housing circumstances of the late twentieth century. A questioning of the assumptions about life course and housing career trajectories is also relevant to policy development to the extent that social policy rests upon such assumptions about the ways in which Australians lead their lives.

To meet this aim the paper is structured into six sections.

Section one introduces the key concepts of risk society theory (manufactured uncertainty and individualisation) and illustrates their meaning with reference to changes in family life.

Section two considers the implications of manufactured uncertainty and increased individualisation for a key concept in family studies – the family life course.

Section three considers how the economic, political, cultural and demographic structures that supported traditional housing careers have changed in the era since World War II.

Section four sets out how the empirical investigation of risk society theory is to take place, and introduces two lower order concepts – differentiation and disconnectedness.

Sections five and six present analyses of primary and secondary data that consider, in turn, the weight of empirical evidence for differentiation and disconnectedness in Australian housing careers.

The paper concludes by considering the extent of the breakdown in traditional housing career pathways and whether these are being supplanted by processes of individualisation and uncertainty that are indicative of the emergence of a risk society.

Social change, describing its patterns, and explaining why it is occurring, lies at the heart of social research. Yesterday is raked over to provide clues about how and why today is different. Today is enumerated and extrapolated to provide clues about tomorrow.

Contemporary social change, theorists argue, is of such a dimension and quality that it amounts to a transformation, with the industrial era of modern society now giving way to the risk era. ‘Risk society’ refers to a time in which the risks or hazards produced in the growth of industrialism come to dominate contemporary ways of life (Beck 1996). It is millennium bugs rather than plagues of locusts. These ‘manufactured uncertainties’ that define a risk society are said to be the result of social interventions (Giddens 1996:152).

Risk society also has particular implications for family life. The decision of someone living in a western society to get married has changed dramatically. ‘Fifty years ago, someone who decided to marry knew what he or she was doing: marriage was a relatively fixed division of labour involving a specified status for each partner. Now no one quite knows any longer what marriage actually is, save that it is a ‘relationship’, entered into against the backdrop of profound changes affecting gender relations, the family, sexuality and the emotions.’ Giddens (1996:153)

This uncertainty about marriage can be thought of as a manufactured uncertainty because it is a part of the social restructuring of gender, sexual and family relations. Not only has the incidence and timing of marriage altered dramatically over the past 20 years, but the norms and values associated with it – its social meaning – has also been significantly reshaped.

A compounding factor of uncertainty in a risk society is that families, communities, class groups and the like, are increasingly less important in setting the social rules or norms by which we live. This exhaustion of collective sources of meaning leads to a situation whereby individuals, rather than general or traditional social rules, are increasingly responsible for setting the boundaries to the ways in which we lead our lives. Individualisation (Beck 1996: 29–30) is the concept used to refer to this process of individuals navigating their social lives alone.

Consider the example of married life. ‘Couples can [now] create for themselves the normative order of their relationship. Thus, if a couple agree to a certain set of boundaries, the important element is sticking to what is agreed rather than following general or traditional rules which are presumed to accompany ones status as husband or wife’ (Smart 1997: 307). Individuals are increasingly responsible for negotiating their own life patterns.

It is important to note that the opportunities for individualisation, or to plan a biography, are unlikely to be evenly distributed across the population. Social inequality and class remain important dimensions of a risk society affecting opportunities for individualisation (Smart 1997:308). Amongst the well paid and well educated the uncertainty of risk society may present as a host of previously unheralded opportunities. For the disadvantaged, however, such uncertainties are more likely to mean insecurity and a loss of opportunity.

The writing of individual biographies (Smart 1997: 307) is not undertaken in a social vacuum, for secondary agencies and institutions, such as the state, take the place of traditional ties and social forms such as social class and the nuclear family. Key policy changes can have a dramatic impact upon the timing, sequencing and nature of individual life trajectories. For example, if the state were to lower the retirement age, the length of ‘social old age’ would increase for an entire generation (with all the associated opportunities and problems). Simultaneously a redistribution of labour participation to the following younger generations is accomplished. The increased importance of institutions such as government in shaping life situations means that this process is inherently political (Beck 1992: 131–32).

Ironically, at a time when dominant political ideology advocates less rather than more government intervention, the evolving structure of the social fabric positions policy institutions as forces central to the shaping of individual lives.

In understanding this role for social policy and by questioning the assumptions about life course norms that imbue social policy, lies the direct policy relevance of this paper.

One outcome associated with the rise of manufactured uncertainty and individualisation in a risk society is a quantitative change in the diversity of family and household forms. Processes of individualisation lead to the breakdown of more traditional forms of social group which includes the nuclear family. Manufactured uncertainties about marriage (increasing divorce and falling marriage rates), childbirth (decreasing fertility rates), sexuality and gender roles lead to a proliferation of other family and household forms, including increasing proportions of one-parent families, group households and living alone households.

It is not simply that at any one point in time there is an increased diversity of household forms, but that over time any one individual is likely to find their biography littered with an array of living arrangements (Beck (1992:119).

This multiplicity of household forms (the quantitative change), is accompanied by an increased social acceptance of the complex mosaic of family life in late modernity. There is thus also a qualitative change in the social meaning of the diversity of household forms.

The trend towards individualisation has also been identified in relation to family values. Reconciling the goal of personal autonomy with the essentially social nature of human life has been a central tension in western philosophy since the Enlightenment (McDonald 1995:27). The ‘pull’ of this tension over the centuries has undoubtedly been towards increasing personal autonomy or liberalisation. ‘In broad terms, today’s family values reflect the continued extension of individual rights to adults, including the right to determine the ways in which they live their lives . . . the emphasis has been on the rights of the individual family member rather than on the rights of the family as a group unit’ (McDonald 1995:46).

The conceptual framework offered by the life course approach has been widely accepted in family and housing research in recent times and has determined the way we conceptualise, conduct and interpret our findings into policy. The assumptions underpinning the life course approach are, however, brought into question by the rise of individualisation in a risk society.

In general terms, life course analyses seek to study and explain social processes with reference to the unfolding of life’s key stages.1 The life course approach ‘examines divergence of experiences along life careers and their sequencing, combinations and timing. Individuals are understood in terms of the ongoing effects of earlier life experiences as well as their current circumstances. The approach requires a broadening of the strictures of traditional life cycle analyses to include topics such as divorce, remarriage and migration’ (Kendig 1990:137). According to Bush and Simmons (1990: 155–156), life course analyses place an emphasis upon socially defined, age-linked roles or age-graded norms, which are clear and widely accepted in a given society. It is not that there is one particular sequential set of roles, for a number of routes through the life course are possible. However, the concept maintains that the character of earlier life experiences may narrow future alternatives and the age-related norms provide a social timetable for major role transitions (Bush and Simmons 1990:156). ‘An individual may postpone higher education to “find” him- or herself, thus deviating from both the age-grade norms and work ethic norms’ (Bush and Simmons 1990:156).

Two key principles therefore underpin life course analyses: first, age-related norms – that the life course consists of a series of socially defined, age-linked norms, or age-graded norms, which are clear and widely accepted in a given society; second, linear connectedness – that earlier life experiences have ongoing and important implications for current and later life experiences.

While allowing for a diversity of pathways and transitions through life, the concept of a life course, is predicated on a ‘sequence of culturally defined age-graded roles and social transitions that are enacted over time’ (Caspi et al. 1990:15). The biography of the life course is one of established social rules and norms, although it allows for deviations from these. Yet, importantly, alternative pathways are treated as deviations from the norm. In contrast, the concepts of risk society question a logic that rests on linear movement or even deviant movements in family life courses. Instead, manufactured uncertainty addresses frequent, socially produced, radical disjunctures (rather than transitions) as the ‘norm’ of social life, with a wide-range of life course options in existence. None of this array of life course options is seen as deviant because a qualitative shift in the social norms grants such diversity a ready acceptance.

It is here that the notion of a life course and processes of increasing individualisation and uncertainty are in contradiction. The life course is defined by socially accepted norms, with earlier life experiences impacting upon those in the future. Yet individualisation in a risk society points to the breaking down of socially accepted norms, and manufactured uncertainty suggests that with radical disjunctures in people’s lives, earlier life experiences will no longer necessarily narrow those of the future. Hence, we may speak of a disconnecting of biographical pasts and futures. In a risk society what has gone before becomes disconnected from what will happen in a person’s future due to increased uncertainties and the individualised responses to these uncertainties. Previous certainties of social life dissolve as, for example, an apprenticeship no longer guarantees a lifetime of secure, skilled employment; a university education no longer ensures a lifetime of well paid professional employment; partnering does not inevitably lead to marriage; and marriage does not inevitably lead to the birth of children.

The extent to which the rise of manufactured uncertainty and processes of individualisation are altering contemporary Australian life courses is the focus of this paper. By focusing on one particular aspect of the life course – family housing careers – the paper examines empirical evidence for the transformation to a risk society.

1 The focus of this paper is upon social outcomes of life course processes rather than the developmental outcomes examined in life stage, life span and some life course work (see Bush and Simmons 1990).

The weight of evidence suggests that the late twentieth century represents a significant juncture in social life. The scale and pace of social change over the past 20 years are sufficiently well documented that we need not rehearse these arguments in general,2 but rather can consider the implications of this widespread social change for housing careers in particular.

The economic, political, cultural and demographic conditions of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s ‘bedded down’ as the typical Australian housing career. The economics that shaped the traditional housing career included factors such as the prevailing mortgage interest rate, house prices, the rate of inflation, wage rates, and unemployment. From 1943 to 1961 the home ownership rate rose from 43 per cent of households to 70 per cent (Bourassa et al. 1995:83). This growth was in part aided by a considerable expansion of the labour market which saw, between 1950 and 1974: aggregate employment grow by 73 per cent – faster than the population overall; the workforce participation rate go over the 60 per cent mark; and unemployment stay low. Male average weekly earnings increased well ahead of inflation (Berry 1998:4). Other key economic factors included low and stable unemployment, with stable underlying inflation which contributed to low and stable mortgage rates at under 6 per cent with real rates between 2 and 3 per cent (Yates 1994:29). Consequently, house building activity was prolific with residential investment growing at an average of 6 per cent per annum through the 1950s and almost 7 per cent in the 1960s (Berry 1998:6).

In the political sphere, the 1950s and 1960s represented a time of expansion in the welfare state that included support for home purchase through protected home loan interest rates. Wide access to public housing through generous terms of purchase also provided a stepping stone to home ownership. Such political supports were engendered by fears of the rise of communism that cast home ownership as a bulwark against bolshevism (Winter 1994:4–5). A cultural scene dominated by the post-war search for security and stability also ensured considerable demand for the uptake of home ownership, a demand that was strengthened by a demography that included rapid population growth and high international migration levels (Australian Urban and Regional Development Review 1995; Chapter 2 in Berry 1998:4).

By the 1970s, however, instability had begun to characterise Australian society, so that in the 1980s and 1990s the key economic parameters were continuing high unemployment, increasing income inequalities, rising nominal and real interest rates, and relatively stagnant real wages (Bourassa et al. 1995; Yates 1994). In housing terms this translated as rising real house prices and a rapid decline in affordability in the late 1980s.

As the economic fundamentalist state came to replace the welfare state, housing policy registered a weakening of supports that in the past had helped bridge the links between particular life cycle stages and housing outcomes. Restrictions on the sale of public housing and the cancelling of the provision of low interest loans for those who may have wanted to buy in the late 1970s, followed by the disappearance of the First Home Owners Scheme in 1990, removed policy supports that assisted young, low income families to access home ownership. Furthermore, the introduction of compulsory superannuation and higher education fees positioned a number of competing priorities for the limited earning and saving capacity of younger households. A demographic shift had also taken place so that the dominant trends were: the ageing of the population with smaller percentages of younger households; the postponement of marriage and increasing divorce rates leading to a greater proportion of single-person and sole-parent households; and a rise in international migration in the late 1980s (Bourassa et al. 1995).

Berry summarises the impact of all these changes. ‘From the early 1970s onwards and particularly over the past 15 years, housing provision – both as a process and as a set of outcomes – has become more uncertain, volatile and problematic, for residents, investors, builders, financiers and, not least, governments. The neat, functional fit in the earlier post-war period between housing aspirations, employment opportunities, population growth, household formation, land availability, savings flows and government policies appears to be loosening. For example . . . in a world of low inflation, low job security, high unemployment, high capital mobility and increasing economic inequality, the rate of home ownership among younger Australians appears to be falling in the 1990s . . . In short, the 1980s may be seen as a watershed in Australian society and the Australian housing system, the point from which new processes and outcomes emerged, reflecting greater diversity, complexity, uncertainty and . . . inegalitarianism’ (Berry 1998: 2–3).

The contemporary period is clearly one of remarkable structural change – economically, politically, culturally and demographically. These trends have the potential to reshape Australian housing careers dramatically. The following sections map out the methodological and analytical strategies designed to consider the biographical responses in housing careers to these altered structural circumstances, focusing upon evidence of differentiation and disconnectedness.

2 See for example, Bagguley et al (1990), Beilharz et al. (1992), Castles et al. (1996), Catley (1996), Davidson (1997), Fagan and Webber (1994), Kalatzis and Cope (1997), and Kelly (1994).

This section centres on how we can empirically measure the abstract concepts of risk society, discussed above. The data to be drawn upon, the analytical techniques used and the mid-range concepts introduced to articulate between the empirical data and the key concepts of risk society are each detailed. The ontological approach, which refers to our assumptions about the ways in which society is constructed, avoids a position which assumes that individuals are mere pawns in a game of society-wide or structural change, by focussing upon both agents and structures, so that ‘family members become active agents rather than resembling the furniture in a household which is moved by external forces (Smart 1997:307). This approach follows Beck and Giddens who link the family to wider developments by incorporating ideas of change emanating from within the private sphere as well as from without (Smart 1997:309).3

Data sources

The series of links between home ownership, Australian cultural identity, and life course certainty makes home ownership and housing careers an important empirical reference point for the study of transformation to a risk society. This empirical examination is undertaken with primary and secondary data, searching for cohort-related (that is, over time) changes in the nature of Australian housing careers.

In the primary data analysis, the housing careers are constructed from retrospective data from the Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS), a national random survey of 25–70 yearolds conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies in late 1996. A total of 2685 respondents were surveyed, 2633 of whom are included in the cohort analysis presented in this paper. Although the data are retrospective, given the significance of housing career events in family life it is reasonable to anticipate a high degree of recall accuracy for such data (Foddy 1993: 90–100).

The analysis also draws upon secondary data from two other studies – the Australian Family Project, and the Australian Family Formation Project.

The Australian Family Project (AFP), based on two retrospective longitudinal surveys, was conducted by the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University in 1986. The surveys contain information on the life histories of 4729 respondents, all of whom are included in the cohort analysis presented in this paper. As reported in Anderton and Lloyd (undated), AFP data includes four cohorts.

The Australian Family Formation Project (AFFP), conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies in 1981 and in 1990/91, comprises a longitudinal study of a national sample of respondents born between 1947 and 1963. The first wave of the study was conducted by face-to-face interview in 1981, then respondents were surveyed again, by mail, in 1990/91. The first wave of the study includes 2544 respondents, and wave two includes 1488 respondents, 1459 of whom are included in the cohort analysis presented in this paper. The AFFP includes two cohorts.

| Australian Life Course Survey 1996 | Australian Family Project 1986 | Australian Family Formation Project 1981, 1990/91 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Year Cohorts | Age 1996 | Cohorts | Age 1986 | Cohorts | Age 1990 |

| Cohort 1 1927 – 1931 | 64 - 69 | ||||

| Cohort 2 1932 – 1936 | 59 - 64 | Before 1936 | 51 + | ||

| Cohort 3 1937 – 1941 | 54 - 59 | 1936 – 1945 | 41 - 50 | ||

| Cohort 4 1942 – 1946 | 49 - 54 | ||||

| Cohort 5 1947 – 1951 | 44 - 49 | 1946 – 1955 | 31 - 40 | 1947 – 1954 | 36 - 43 |

| Cohort 6 1952 – 1956 | 39 - 44 | ||||

| Cohort 7 1957 – 1961 | 34 - 39 | 1956 – 1969 | 17 - 30 | 1955 – 1963 | 27 - 35 |

| Cohort 8 1962 – 1966 | 29 - 34 | ||||

| Cohort 9 1967 – 1971 | 24 - 29 | ||||

| Total N | 2633 | 4729 | 1459 | ||

Note: Australian Life Course Survey 1996 cohorts are based on month and year of birth hence the ages of cohorts overlap. Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1998.

Cohort analysis

In order to compare differentiation and disconnectedness in housing career patterns and pathways over time, the primary data (ALCS) are divided into nine birth year cohorts. Secondary data (AFP and AFFP) are also presented in birth year cohorts matched to the primary data. Table 1 shows how cohorts from the respective data sources correspond with one another.

Mackay’s work on generational differences in Australia (1997) places ALCS cohorts 1 and 2 in the ‘lucky generation’, cohorts 4, 5, 6 and 7 in the ‘stress generation’, and cohorts 8 and 9 in the ‘Age of Redefinition’.

Although ALCS cohorts 1 and 2 endured the deprivation of the Great Depression, Mackay refers to them as the ‘lucky generation’ because they ‘enjoyed that unique combination: a set of sound values shaped by the hardships of their parents’ generation, and a subsequent period of economic comfort and prosperity undreamed of by those parents’ (Mackay 1997:10).

Cohorts 4, 5, 6 and 7 are in Mackay’s ‘stress generation’, so called because: ‘On the one hand, they were the children of the boom years of the 1950s and 1960s . . . On the other hand, they were the children of the Cold War . . . This created a most peculiar tension . . . between belief in a rosy, easy future . . . and no future at all (Mackay 1997:10). This tension leads Baby Boomers to think of themselves as stressed: ‘”Why does it all have to be so hard?” is a question they are often asking themselves as they settle into the difficulties of a second or third marriage, and the strain of raising someone else’s children’ (Mackay 1997:11).

Cohorts 8 and 9 were born in Mackay’s Age of Redefinition. Mackay believes they remain close to the ideals and values of the Baby Boomers in some ways, and in other ways, close to the 1970s Options Generation that follows them. The Options Generation was born into one of the most dramatic periods of social, cultural, economic and technological development in Australia’s history – the age of uncertainty: ‘their experience of impermanence and unpredictability has taught them one big, central lesson: keep your options open’ (Mackay 1997:140).

Differentiation and disconnectedness

In order to connect and interpret the empirical reality of change in housing careers to the conceptualisation of risk society, the paper employs two lower order concepts: differentiation and disconnectedness.

The concept of differentiation refers to the weakening of the age-related norms that are central to life course analyses. Differentiation occurs in a risk society as individuals respond to structural uncertainties with an individual orientation rather than one derived from a collective norm (for example, family or class) about what one should be doing by a particular age.

The measurement of differentiation is less concerned with the average or median age at which a cohort achieve a particular event, but rather with the span of ages over which people are, for example, first entering home ownership. Change in the median age of attaining a housing career event would simply measure whether an age-related norm has got younger or older.

However, differentiation can be measured by examining the number of years between the 25th percentile of a particular cohort attaining a particular housing career event and the 75th percentile. If the age span at which this activity is undertaken is lengthening across cohorts, then there is weakening of the age-related norm – the event is less likely to have taken place within a limited age frame. If, on the other hand, the age span is narrowing for a given activity, this suggests there is a strengthening of the age-related norm. The 25th to 75th percentiles are selected to measure the activity associated with a particular event as this includes the middle majority – neither the first group in nor the last.

The concept of disconnectedness refers to a fracturing of linearity in the development of housing careers. Life course analyses assert that earlier life course events shape opportunities and outcomes later in the life course – the past and the future are connected.

However, the rise of manufactured uncertainty and individualisation in a risk society points to radical disjunctures in housing career pathways. Evidence of disconnectedness in the data would comprise a breaking of the links between a particular housing outcome and a particular life course phase, or a re-ordering of the pattern of life course and housing career events. The re-ordering of events is most important at the level of social meaning because the fractured sequence represents a disconnection of the social meaning from the life course events that previously provided a pathway through life.

3 Section five considers structural change and sections six and seven the biographical responses.

Differentiation as a social process refers to the dissipation of age-related norms – that is, an increasing span of years over which a cohort attains a particular housing career event, thus weakening its character as an age-related norm. Drawing upon primary and secondary data, this section examines evidence of differentiation in relation to leaving the parental home and entry to home purchase.

Leaving the parental home

Anderton and Lloyd (undated) analyse cohort differences in age of leaving the parental home using data from the Australian Family Project (AFP 1986). Table 2 presents data for women and men in cohorts 1 and 4, comparing the age at which 25 per cent and 75 per cent of the cohort had left the parental home. If the age span between the 25th and 75th percentiles is greater for cohort 4 than cohort 1, this can be interpreted as a weakening of the age-related norm of leaving the parental home. If the age span between the 25th and 75th percentiles of cohort 4 is less than that of cohort 1, this can be interpreted as a strengthening of the age-related norm of leaving the parental home.

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Cohorts in 1986 | Age of Cohorts in 1986 | |||||||

| 51+ | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-17 | 51+ | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-17 | |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

| 25 percentile | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| 50 percentile | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 20 |

| 75 percentile | 27 | 25 | 24 | 27 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 23 |

Source: Australian Family Project (AFP), Australian National University, 1986. Reproduced from Anderton and Lloyd (undated) p.39, Table 2.

| Men | Women | |||

| Age of Cohorts in 1990 | Age of Cohorts in 1990 | |||

| 43-36 | 35-27 | 43-36 | 35-27 | |

| C1 | C2 | C1 | C2 | |

| 25 percentile | 17 | 18 | 17 | 18 |

| 50 percentile | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 |

| 75 percentile | 22 | 23 | 21 | 21 |

Note: In 1990 Cohort 1 was aged 36–43, Cohort 2 was 27–35 years. Source: Calculations made using Australian Family Formation Project (AFFP), Wave 1 and Wave 2, Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1981–91, unpublished data.

Among women, the middle 50 per cent of cohort 1 left the parental home between the ages of 20 and 24. By cohort 4 this middle 50 per cent of women left the parental home between the ages of 19 and 23. With the age span between 25 per cent and 75 per cent of women leaving the parental home being four years for cohort 1 and four years for cohort 4, there would appear to be no change in the age-related norm of leaving the parental home between the 1950s and the late 1970s-early 1980s. Similarly for men, the age span was seven years in cohort 1 and seven years for cohort 4, indicating no change in the agerelated norm of leaving the parental home.

This trend can be brought more up to date by drawing upon the second wave of the Australian Family Formation Project (AFFP 1990/91) (Table 3). Among women aged 43–36 (in 1990) the span between the 25th and 75th percentiles leaving the parental home was four years – that is, the middle 50 per cent of this cohort left the parental home between the ages of 17 and 21. In the younger cohort of women, aged 35–27 (in 1990), the age span between the 25th and 75th percentiles leaving the parental home had narrowed to three years – between the ages of 18 and 21 years. For men, the age spans are five years for the older cohort and five years for the younger cohort. Thus, both data sets – AFP (1986) and AFFP (1990/91) – indicate little, if any, change in the age-related norm of leaving the parental home, and thus little evidence of differentiation occurring.

In terms of the uneven distribution of manufactured uncertainty and individualisation, there are clear gender differences in the strength of the age-related norm of leaving the parental home. Both Tables 2 and 3 show a narrower span of ages over which women leave the parental home than men. This suggests that the age-related norm of leaving the parental home is stronger for women and that the opportunity for individualisation is less. Yet, the consistency of this pattern across the cohorts suggests that the theorised increase of individualisation has had little to do with these gender differences, or that the social processes that used to create such gender differences have now been supplanted by individualisation, but with the same overall outcome.

Entry to home purchase

Entry to home purchase has been the defining moment of post-World War II housing careers in Australia, and thus an important reference point for analysis of change. Anderton and Lloyd’s (undated) analysis of the Australian Family Project (AFP 1986) provides information about the extent of age-related norm dissipation that has occurred over time.

Table 4 presents the data for entry to home purchase by women and men for cohorts 1 to 4 (cohort 3 is used for analysis because 75 per cent of cohort 4 were yet to enter home purchase). For women, the age span between the 25th and the 75th percentile for entry to home purchase in cohort 1 was 12 years (ages 24–36), and in cohort 3 ten years (ages 23–33). For men, the age span in cohort 1 was 14 years (ages 29–43) and in cohort 3 just seven years (ages 26–33). Thus, for both men and women the middle majority have been able to enter home purchase within a shorter and shorter time frame. This finding represents a strengthening of the age-related norm of entering home purchase over time, with again little evidence of differentiation.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Age of Cohorts in 1986 | Age of Cohorts in 1986 | |||||||

| 51+ | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-17 | 51+ | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-17 | |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

| 25 percentile | 29 | 28 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 23 |

| 50 percentile | 34 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 29 | |

| 75 percentile | 43 | 36 | 33 | 36 | 34 | 33 | ||

Notes: The figure for the 75th percentile for women (51+) has been corrected from original figure. Estimates for the 50th and 75th percentiles cannot be obtained for the youngest cohort (30–17) as approximately 30 per cent of that cohort had entered home ownership at the time of the survey.

Source: Australian Family Project (AFP), Australian National University, 1986. Reproduced from Anderton and Lloyd (undated) p.72, Table 16.

Analysis of the Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS 1996) confirms this finding. Table 5 presents the data for cohorts 1 through to 9 for age of entry to home purchase at the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles, for both women and men. For women, the age span between the 25th and 75th percentiles for entry to home purchase has fallen from 14 years for cohort 1 (ages 23–37) to 11 years for cohort 8 (ages 23–34). The middle majority of women in cohort 8 were thus able to enter home ownership in three fewer years than cohort 1. Examination of the age span between the 25th and 50th percentiles enables the analysis to be brought as up to date as possible – that is, through to cohort 9 of whom 75 per cent had yet to enter home purchase at the time of the survey. The strengthening of the age-related norm of entry to home purchase for women is again confirmed, with the age span narrowing from six years in cohort 1 (ages 23–39) to three years in cohort 9 (ages 24–27).

Analysis of entry to home purchase by men demonstrates the same overall trend of a strengthening age-related norm. The age span between the 25th and 75th percentiles has fallen from 13 years in cohort 1 (ages 27–40) to 11 years in cohort 7 (ages 24–35) (only 66.7 per cent of men in cohort 8 had entered home ownership). Comparing the 25th to the 50th percentiles of cohorts 1 and 7, the age span has remained constant at three years.

In interpreting these results it is important to remember that the entry to home ownership activity of all cohorts but particularly the youngest, cohort 9, has been truncated at the point in time in which the survey was conducted. We simply do not know how many people in the most recent cohort are going to enter home ownership in the future or at what age they are going to do this. If cohort 9 reaches similar levels of home ownership to their forbearers, but at later ages, the median age of entry and the 75th percentile age would increase, resulting in a weakening of the age-related norm of entry to home ownership.

Whilst the early cohorts entered home ownership at a time when the tenure was expanding rapidly, the later cohorts entered at a time when the tenure was stable or decreasing. The rapid expansion of home ownership in the earlier period may, therefore, have included a number of older entrants to home ownership in these early cohorts, weakening the age-related norm. This is in contrast to the later period of stability or decline in the proportion of home owners, when entry appears to be happening as soon as possible.

Any evidence of unevenness in the distribution of manufactured uncertainty and individualisation according to gender is not distinctive in the age-related norm of entering home purchase. Although it is clear from Tables 4 and 5 that women’s agerelated norm for this event is younger than men’s, the span of years over which this takes place is similar. This is perhaps because entry to home purchase has typically been linked with the formation of a partnership. For the early cohorts, entry to home purchase was typically preceded by marriage, and for later cohorts the cost of entry to home purchase has demanded the availability of two incomes to service the mortgage costs.

| Men | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Cohorts in 1996 | |||||||||

| 69-64 | 64-59 | 59-54 | 54-49 | 49-44 | 44-39 | 39-34 | 34-29 | 29-24 | |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | |

| 25 percentile | 27 | 26 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| 50 percentile | 30 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 27 |

| 75 percentile | 40 | 41 | 36 | 35 | 39 | 36 | 35 | ||

| Women | |||||||||

| Age of Cohorts in 1996 | |||||||||

| 69-64 | 64-59 | 59-54 | 54-49 | 49-44 | 44-39 | 39-34 | 34-29 | 29-24 | |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | |

| 25 percentile | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 50 percentile | 29 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| 75 percentile | 37 | 38 | 40 | 33 | 36 | 33 | 35 | 34 | |

Note: Australian Life Course Survey 1996 cohorts are based on month and year of birth hence the ages of cohorts overlap. Source: Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS), Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1996.

Summary

To summarise the findings in relation to differentiation: for both women and men there appears to be no change in the age-related norm of leaving the parental home, and there appears to be a strengthening of the age-related norm in entry to home purchase. These findings suggest that there is little evidence of increased differentiation in Australian housing careers.

Disconnectedness refers to a fracturing of the linearity of life course and housing career events. This may be manifest as either a weakening of the relationship between earlier housing career events and future housing opportunities and outcomes and/or a weakening of the relationship between particular housing consumption outcomes and particular life course phases. Drawing upon primary and secondary data, this section examines evidence of disconnectedness in relation to: first, the finality of first leaving the parental home – that leaving the parental home for the first time has become disconnected from a linearly developing life course; and second, the sequencing of key life course events – that entry to home purchase has become disconnected from marriage and child bearing.

The finality of leaving the parental home

Leaving the parental home has typically been a very important first step toward adult independence, toward marriage and family formation, and thus toward home ownership. If disconnectedness is emerging in relation to leaving the parental home, then one measure of this would be that initial departures from the parental home result in a return to the parental home, rather than a second step toward continuing adult independence as the linear development of a life course would suggest. If first leaving the parental home is, over time, resulting in increasing proportions of returns to the parental home then first leaving the parental home is becoming increasingly disconnected from the life course events and linear developments that it has typically been associated with.

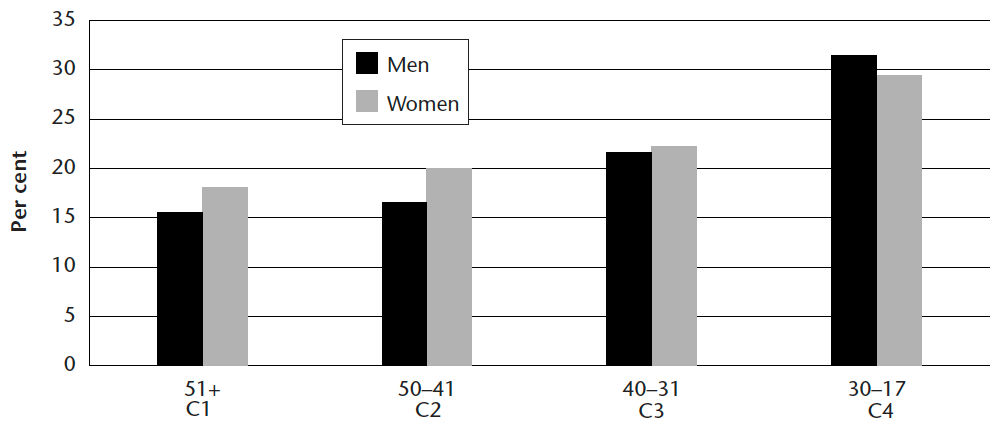

Figure 1 is reproduced from analysis by Anderton and Lloyd (undated) of the Australian Family Project (AFP). The figure illustrates that over time increasing proportions of each cohort have been returning, after initial departure, to the parental home. ‘The proportions of women have increased from almost 18 per cent of cohort 1 to about 30 per cent of cohort 4. Among men the same trend is evident. In cohort 1 only 16 per cent of men returned home, while in cohort 4 almost 32 per cent of men returned. The proportions returning home have almost doubled for both females and males’ (Anderton and Lloyd, undated: 49, Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Proportions of cohorts returned home after initial departure, by gender: Australian Family Project (1986)

Source: Australian Family Project (AFP), Australian National University, 1986.

Figure reproduced from Anderton and Lloyd (undated) p.49, Figure 3 using value estimates.

Young’s (1987:37) analysis of the first wave of the Australian Family Formation Project (AFFP 1981) confirms these trends. Comparing returns to the parental home for those aged 20–24, 25–29 and 30–34 (in 1981), 59 per cent, 49 per cent and 38 per cent respectively had returned to the parental home (Table 6). The younger cohorts were more likely to return to the parental home than their older counterparts. These findings suggest that initial departures from the parental home are increasingly less likely to be connected to a continuing adult independence. There is increasing uncertainty about when the transition to adult independence has commenced. To put it another way, the transition to adult independence has become disconnected from a particular housing outcome of independent living. The new social meaning of adult independence may well be establishable within the parental home.

Further evidence that leaving the parental home is becoming disconnected from a linear life course sequence is that the frequency of returns to the parental home is also increasing (Table 7). Anderton and Lloyd (undated: 49–50, Table 9), demonstrate that among those returning home, 83 per cent of women in cohort 1 returned home only once. By cohort 4 less than 69 per cent returned home only once. Furthermore, returns thrice or more among women had increased from 6 per cent in cohort 1 to 16 per cent in cohort 4. The picture is not as dramatic for men, but the trend is in the same direction: single returns had fallen from 76 per cent in cohort 1 to 73 per cent in cohort 4; and three or more returns had risen from 10 per cent in cohort 1 to 13 per cent in cohort 4.

A third way of understanding the way in which initial departure from the parental home is becoming disconnected from life course linearity is to examine change in what is deemed an appropriate reason for leaving home – that is, change in the social meaning of the norm. Anderton and Lloyd (undated: 41, Table 4) identify that for both women and men in cohort 1, the key reason for leaving the parental home was to get married – 61 per cent of women in cohort 1 left for this reason and 44 per cent of men. As such, marriage was the social norm on leaving the parental home. However, by cohort 4, although marriage is still the main reason for leaving the parental home, fewer and fewer are leaving for this reason as time passes, leading to an increasing disconnection between leaving the parental home and marriage. Only 42 per cent of women in cohort 4 left the parental home for this reason and 31 per cent of men. Here we point to the impact of an increased diversity of life course options for young adults, one outcome of which is falling marriage rates.

| Sons | Daughters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | % | n | % | n |

| 20 - 24 | 59 | 260 | 53 | 294 |

| 25 - 29 | 49 | 318 | 37 | 341 |

| 30 - 34 | 39 | 349 | 30 | 337 |

Source: Australian Family Formation Project (AFFP), Wave 1, Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1981. Reproduced from Young (1987), p.37, Table 4.8.

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Cohorts in 1986 | Age of Cohorts in 1986 | |||||||

| Times returned | 51+ | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-17 | 51+ | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-17 |

| Once | 76 | 75 | 77 | 73 | 82 | 78 | 74 | 69 |

| Twice | 15 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Three or more | 10 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 16 |

| Total per cent | 101 | 99 | 100 | 101 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| N | 61 | 73 | 128 | 159 | 70 | 112 | 190 | 201 |

Note: Totals do not add to 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: Australian Family Project (AFP), Australian National University, 1986. Reproduced from Anderton and Lloyd (undated), p.50, Table 9.

Young’s (1987) analysis of AFFP (1981) paints an even more dramatic picture of the same trend. Amongst 30–34 year-old women (in 1981) that had left the parental home, 49 per cent had done so to get married. Among the younger cohort of women who had left home (aged 20–24 in 1981), only 29 per cent had done so to get married. Among men who had left the parental home, the trend in the data is the same, with 35 per cent of the 30–34 year-olds leaving the parental home to get married but just 11 per cent of the 20–24 year-olds.

The uneven distribution of manufactured uncertainty and individualisation is perhaps also apparent in returns to the parental home. As Figure 1 and Table 6 suggest that men are more likely to return to the parental home than women, this can be interpreted as men experiencing a greater degree of disconnectedness than women. However, it should be noted that this gender disparity is apparent across the cohorts, which poses a problem for any analysis that promotes the current era to be one that is particularly different from yesteryear. If it is the case that the social processes have changed but the manifestations remain the same (at least with regard to gender difference in returns to the parental home), then it is possible that the higher levels of disconnectedness apparent for men, could stem from experiencing a greater degree of uncertainty – although clearly one would wish to explore data on a diversity of life course events before settling upon such an explanation.

With regard to leaving the parental home, increased disconnectedness is apparent as an increased likelihood of returns to the parental home, an increased frequency of returns to the parental home, and a decrease in departures from the parental home to get married. These first two trends indicate that the first stage of Australian housing careers is becoming disconnected from a second stage of continuing adult independence. Rather than initial departures from the parental home commencing a linearly advancing life course, this first step is more likely to be circular and retrograde – that is, back to the parental home. The falling proportions leaving the parental home to get married underlines a change in the social meaning of this housing career norm, disconnecting it from this other key life event.

Home purchase, marriage and child bearing

A second means of investigating the emergence of disconnectedness in Australian housing careers is to examine the strength of links over time between particular housing career events and other life course events. The hallmark of the Australian housing career has been the link between marriage, birth of a first child and entry to home purchase (Kendig 1981, 1984, 1990). These key life course events have typically been connected by a sequencing that sees marriage followed by the birth of a first child and then entry to home ownership to provide a stable home base for the raising of that family. Disconnectedness of this sequencing would comprise a re-ordering of the sequence whereby home ownership would no longer follow marriage and birth of a first child.

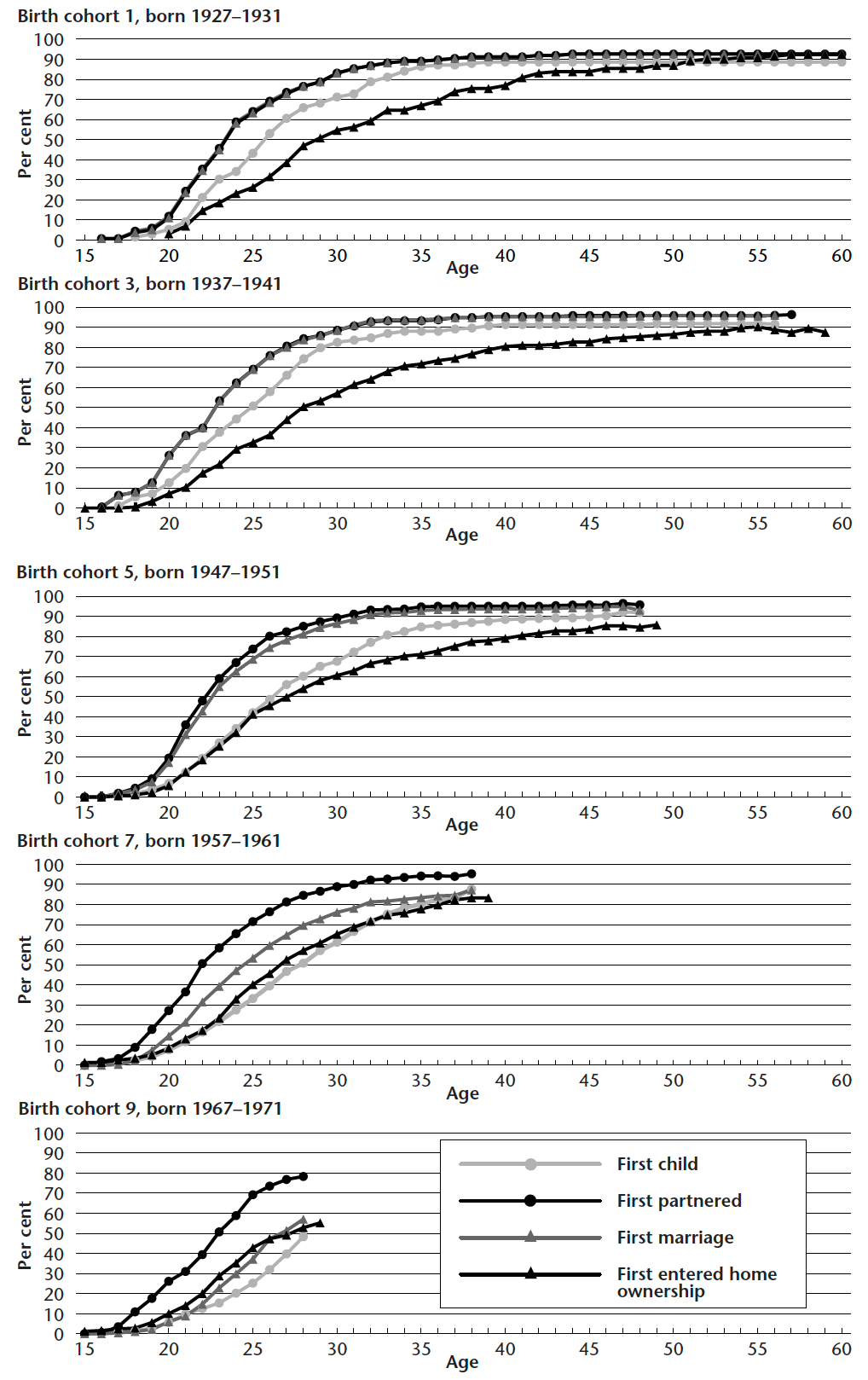

Figure 2 shows the proportions of Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS) cohorts 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 that have attained first entry to home ownership, first marriage, first partnering, and birth of first child, by each year of age.

Figure 2. Alternate birth cohorts, showing proportions of cohorts experienced life events by each year of age: Australian Life Course Survey (1996)

Note: Data points on the graph lines are only drawn where they are supported by more than 100 cases.

Source: Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS), Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1996.

It is clear that in cohorts 1 and 3 the sequencing of life course events was first partnering and first marriage coinciding, followed by birth of first child and then first entry to home ownership. In cohort 5 the same basic patterning exists, except that first partnering begins to precede first marriage very slightly, and birth of first child and first entry to home ownership begin to coincide through to age 26. By cohort 7 the delaying of first marriage has become clear with first partnering preceding it from ages 18–38. Relatedly, home ownership begins to precede birth of first child in this cohort from age 23–31. By cohort 9, first entry to home ownership has come to precede first marriage and birth of first child between the ages 19–25.

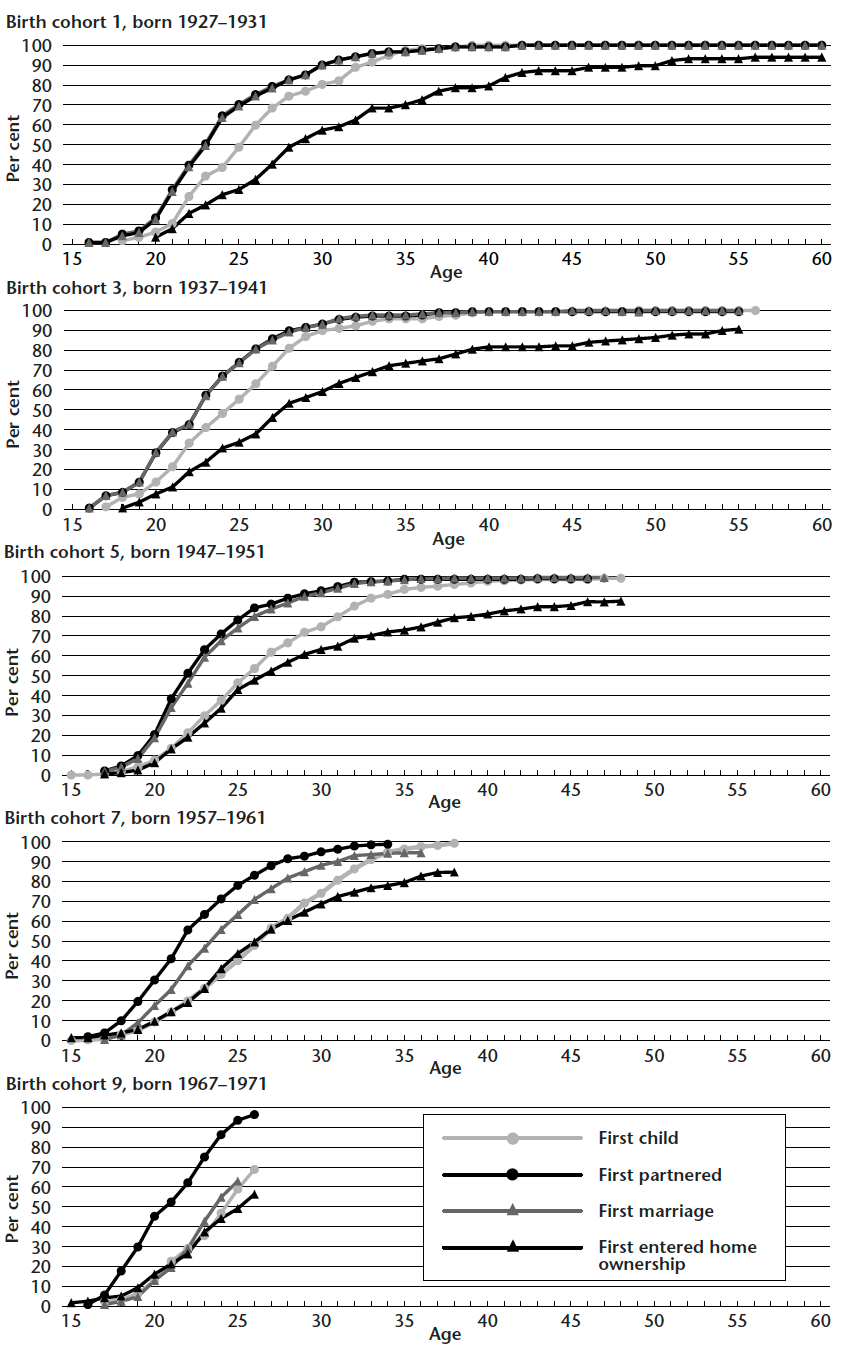

Greater insight as to the nature of the changes can be gained by reproducing the life course event curves only for those who have ever had children. Figure 3 shows that the re-ordering of events is not as dramatic for this group of families though the change is still considerable. Rather than home ownership coming to precede marriage and birth of first child for families with children, the sequencing has changed from a step-wise marriage, birth of first child, enter home ownership – to each of these events coinciding perhaps three or four years after first partnering.

That the re-ordering of events is not as dramatic for families with children suggests that the key driver of change in the aggregate picture for all households, is the increased diversity of household types. Families with children simply make up a smaller proportion of all households in cohort 9 than they did in cohort 1, and it is this increased diversity of household types that are pursuing different life course and housing career trajectories when compared with the traditional nuclear family. There is, however, evidence of change in relation to this latter group as delays in marriage and birth of first child mean that these two events now coincide with entry to home ownership.

Summary

To summarise the findings in relation to disconnectedness, it is clear that for initial departures from the parental home and home purchasing, these housing career events are becoming increasingly disconnected from a linearly developing housing career and life course. The data on initial departures from the parental home demonstrate that it is no longer a first step along a linearly developing life course. Instead, first leaving the parental home is increasingly more likely to result in the circularity of returns to the parental home, increased frequency of returns, and disconnection from marriage. Home ownership has become disconnected from the key life course events of first marriage and birth of first child, primarily because of an increased diversity of household types who whilst still entering home ownership are doing so for different reasons. These findings suggest there is some evidence of increased disconnectedness in relation to Australian housing careers.

This paper set out to reconceptualise Australian housing careers through risk society theory, to provide a means for understanding the altered life course and housing career circumstances of the late twentieth century. Evidence of manufactured uncertainty and increased individualisation were sought by examining whether contemporary housing careers are characterised by increased differentiation and disconnectedness.

The paper details change in the structural conditions of housing careers, and individuals responses to these changed conditions. Data analysis reveals no evidence of increased differentiation in housing careers. For example, a recent cohort’s entrants to home ownership are likely to have attained this within a narrower span of years than their predecessors. Interpretation of the reasons for this trend must offset the strengthening of this age-related norm against the reduced proportion of households entering home ownership. Although age related norms for both leaving the parental home and entry to home ownership remain strong, the youngest cohorts are both leaving home and entering home ownership for different reasons than the oldest cohorts. Fewer young people are leaving home to marry, and entry to home ownership is occurring before the marriage and child bearing phases of the life course.

With regard to disconnectedness, the data analysis found considerable evidence that housing careers were becoming increasingly disconnected, with linear progress dissipating and events earlier in the life course becoming dissociated from later outcomes and opportunities. For example, initial departures from the parental home are less likely to be the first step on the road to a linearly advancing independence, and home ownership is less likely to be preceded by marriage and childbirth. The findings suggest that while the re-ordering of events is less dramatic for families with children than for all families, change at the aggregate level is evident and is due to an increased diversity of household types.

With regard to the uneven impact of manufactured uncertainty and individualisation, a limited consideration of gender differences was possible with the available data. Although there are clear gender differences in particular housing career events, associating these differences with the emergence of a risk society is difficult due to the apparent constancy of this unevenness over time.

Figure 3. Alternate birth cohorts, showing proportions of cohorts experienced life events by each year of age, for only those ever had children: Australian Life Course Survey (1996)

Note: Data points on the graph lines are only drawn where they are supported by more than 100 cases.

Source: Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS), Australian Institute of Family Studies, 1996.

The evidence examined for the emergence of risk society in this paper, then, is contradictory but of course partial, focused primarily upon housing careers, rather than marital, fertility or employment careers, with the most recent and perhaps most interesting cohorts truncated by the date of the survey. Further empirical exploration of the emergence of risk society will also need to take account of class, ethnic and gender differences across the population. While the housing careers data presented here differentiate between the experience of women and men, these differences were not a central focus of this paper. However, it is clear that manufactured uncertainty and individualisation will be experienced unevenly across the population and such differences will need to be accounted for in any future analysis. Furthermore, the Australian Life Course Survey (ALCS 1996) was, as its name suggests, designed within a life course paradigm, rather than a risk society paradigm. A data instrument specifically designed to answer the questions posed by a risk society may provide a more accurate basis for the empirical grounding of the concepts of manufactured uncertainty and individualisation.

The empirical investigation of such theoretical questions about the nature of social life continues to be important, not least because assumptions (right and wrong) about contemporary family life permeate our social policy frameworks. Whether it be youth allowances, population projections or superannuation policy, all rest upon assumptions about age-related norms and linear transitions and connections. The possibility of transformation to a risk society fundamentally challenges these assumptions and obliges us to explore the implications of such social theory for the everyday realities of social policy.

- Anderton, N. & Lloyd. C. (Undated), ‘Residential histories and housing careers of Australians: an event history analysis’, Unpublished draft for the Australian Housing Research Fund.

- Australian Urban and Regional Development Review (1995), Urban Australia: Trends and Prospects, Department of Housing and Regional Development, Canberra.

- Bagguley, P., Mark-Lawson, J., Shapiro, D., Urry, J., Walby, S. & Warde, A. (1990), Restructuring: Place, Class and Gender, Sage, London.

- Beck, U. (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity, Sage, London

- Beck, U. (1996), ‘Risk society and the provident state’, in S. Lash, B. Szerszynski & B. Wynne (eds) Risk, Environment and Modernity, Sage, London.

- Bielharz, P., Considine, M. & Watts, R. (1992), Arguing about the Welfare State: The Australian Experience , Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

- Berry, M. (1998), ‘Unravelling the Australian housing solution: the post-war years’, Mimeo, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Melbourne.

- Bourassa, S., Greig, A. & Troy, P. (1995), ‘The limits of housing policy: home ownership in Australia’, Housing Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 83–104.

- Bush, D. and Simmons, R. (1990) Socialisation process over the life course, Chapter 5 in M. Rosenberg and R. Turner (eds.) Basic Books, New York.

- Caspi, A., Elder, G.H. Jr. & Herbener, E. (1990), ‘Childhood personality and the prediction of life course patterns’, in L. Robins & M. Rutter (eds) Straight and Devious Pathways from Childhood to Adulthood , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Castles G. F. (ed.) (1996) Families of Nations: Patterns of Public Policy in Western Democracies , Dartmouth Publishing Company, Aldershot.

- Catley, B. (1996), Globalising Australian Capitalism, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

- Davidson, A. (1997), From Subject to Citizen: Australian Citizenship in the Twentieth Century , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Fagan, R. H. & Webber, M. (1994), Global Restructuring: The Australian Experience, Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

- Foddy, W. (1993), Constructing Questions for Interviews and Questionnaires: Theory and Practice in Social Research , Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

- Giddens, A. (1996), ‘Affluence, poverty and the idea of a post-scarcity society’, in C. Hewitt de Alcantara (ed.) Social Futures, Global Visions, Blackwell, Oxford.

- Glick, P. (1977), ‘Updating the family life cycle’, Journal of Marriage and the Family, vol. 39, February, pp. 5–13.

- Kalantzis, M. & Cope B. (1997), ‘An opportunity to change the culture,’ in The Retreat from Tolerance: A Snapshot of Australian Society , ABC Books, Sydney.

- Kelly, P. (1994), The End of Certainty, Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

- Kendig, H. (1981), Buying and Renting: Household Moves in Adelaide, Australian Institute of Urban Studies, Canberra.

- Kendig, H. (1984), ‘Housing careers, life cycle and residential mobility: implications for the housing market’, Urban Studies, vol. 21, pp. 271–283.

- Kendig, H. (1990), ‘A life course perspective on housing attainment’, in D. Myers (ed.) Housing Demography: Linking Demographic Structure and Housing Markets , University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

- Kendig, H. & Neutze, M. (1991), ‘Achievement of home ownership among post-war Australian cohorts’, Housing Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 3–14.

- Maher, C. & Burke, T. (1991), Informed Decision Making: The Use of Secondary Data in Policy Studies , Longman Cheshire, Melbourne.

- Mackay, H. (1997), ‘Three generations: three Australias’, Relatewell, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 10–11.

- McDonald, P. (1995), ‘Australian families: values and behaviour’, Chapter 2 in R. Hartley (ed.) Families and Cultural Diversity in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

- National Housing Strategy (1991), The Affordability of Australian Housing, Issues Paper 2, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

- Rowland, D. (1991), ‘Family diversity and the life cycle’, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1–14.

- Smart, C. (1997), ‘Wishful thinking and harmful tinkering? Sociological reflections on family policy’, Journal of Social Policy, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 301–321.

- Smith, S. (1989), Gender Differences in the Attainment and Experience of Owner Occupation in Australia , Working Paper No. 19, Urban Research Unit, Australian National University, Canberra.

- Stapleton, C. (1980), ‘Reformulation of the family life cycle concept: implications for residential mobility’, Environment and Planning A, vol. 1, no. 12, pp. 1103–1118.

- Winter, I. (1994), The Radical Home Owner: Housing Tenure and Social Change , Gordon & Breach, Melbourne.

- Yates, J. (1994), ‘Home ownership and Australia’s housing finance system’, Urban Policy and Research, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 27–39.

- Young, C. (1987), Young People Leaving Home in Australia, Australian Family Formation Project Monograph No. 9, Department of Demography, Australian National University, and Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

List of tables

- Table 1 Birth year cohorts from the Australian Life Course Survey (1996), and corresponding cohorts from the Australian Family Project (1986) and Australian Family Formation Project (1981, 1990/91)

- Table 2 Ages in years at which proportions of cohorts left home, by gender: Australian Family Project (1986)

- Table 3 Ages in years at which proportions of cohorts left home, by gender: Australian Family Formation Project (1990/91)

- Table 4 Ages in years at which proportions of cohorts first entered home ownership, by gender: Australian Family Project (1986)

- Table 5 Ages in years at which proportions of cohorts first entered home ownership, by gender: Australian Life Course Survey (1996)

- Table 6 Proportions of cohorts returned home within 10 years of initial departure, by age and gender: Australian Family Formation Project (1981)

- Table 7 Proportion of cohorts returned home after initial departure, showing number of returns by gender: Australian Family Project (1986)

List of Figures

- Figure 1 Proportions of cohorts returned home after initial departure, by gender: Australian Family Project (1986)

- Figure 2 Alternate birth cohorts, showing proportions of cohorts experienced life events by each year of age: Australian Life Course Survey (1996)

- Figure 3 Alternate birth cohorts, showing proportions of cohorts experienced life events by each year of age, for only those ever had children: Australian Life Course Survey (1996)

For their constructive comments on earlier versions of this paper, thanks are due to Trevor Batrouney and John Shelton of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and participants at seminars at the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Department of Infrastructure, Government of Victoria. Thanks are also due to Judith Yates and the ARC Australia’s Housing Choices project team, and to participants in the ‘Changing Households, Changing Housing’ session of the 1998 Australian Population Association Conference, University of Queensland.

Winter, I., & Stone, W. (1999). Reconceptualising Australian housing careers (Working Paper No. 17). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

0 642 39461 X