Fathers and work: A statistical overview

Download Research snapshot

Overview

This article shows the statistical trends in fathers’ employment, for couple and single fathers over recent decades. Trends indicate that while mothers’ employment changes considerably after having a child, fathers’ employment shows little change.

Key messages

-

While fathers today may be more involved in child care, for most families the number of hours fathers spend in employment remains the same before and after having children.

-

Single fathers have more diverse work patterns with higher proportions in part-time work or not employed.

-

Fathers are more likely to choose flexible work or working from home arrangements rather than reduce work hours to fit work around child care.

Family employment patterns

While family employment patterns have shifted over recent decades away from that of a breadwinning father and stay-at-home mother, the shift has seen an increase in maternal employment (generally part-time) but little change in fathers’ employment patterns. This growth in the ‘modified male breadwinner model’ has seen more mothers engaging part-time in paid work while continuing as the primary caregiver (Pocock, 2005). Mothers and fathers still tend to have gendered roles when it comes to work activities in the years after becoming parents.

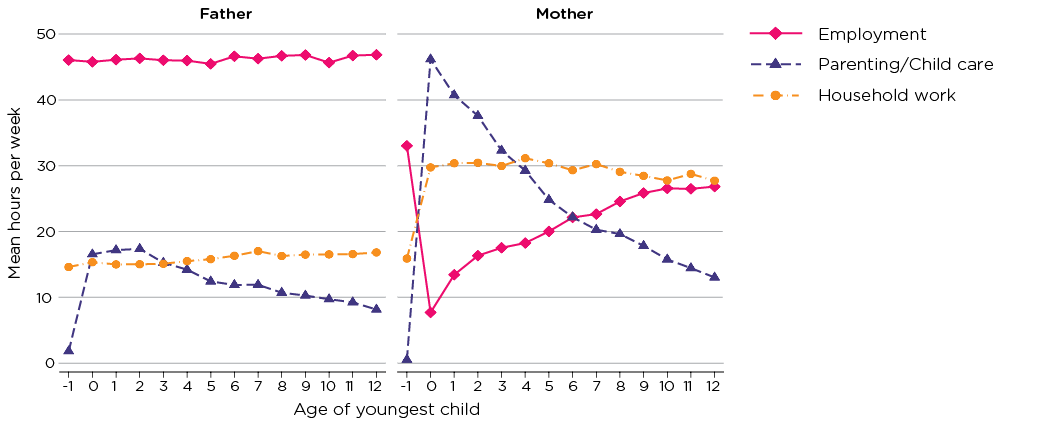

We see this most clearly when comparing time use data for mothers and fathers, and also contrasting these data with their time use in the year before they had their first child (see Figure 1). The number of hours fathers spend in employment remains at the same level before and after having children. Fathers do spend time on parenting and child care when they have young children, fitting this time around their hours of employment. From other time use research, we know that, for many fathers, weekends provide more opportunity for this shared time than weekdays. Mothers’ time use patterns are dramatically different, as their time in employment is lowest when they have an under one-year-old child, gradually increasing thereafter.

Figure 1: Mother and father’s time use up to and after the birth of first child

Note: Age of youngest child = -1 is the year before the first birth.

Source: HILDA, pooled Waves 2 to 161

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2019 (aifs.gov.au/copyright)

Gendered patterns such as these have been observed in other research (see Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer & Robinson, 2000; Craig, Mullan & Blaxland, 2010; Sayer, 2005).

1 These estimates were derived from unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper are those of the author and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

Fathers’ employment participation

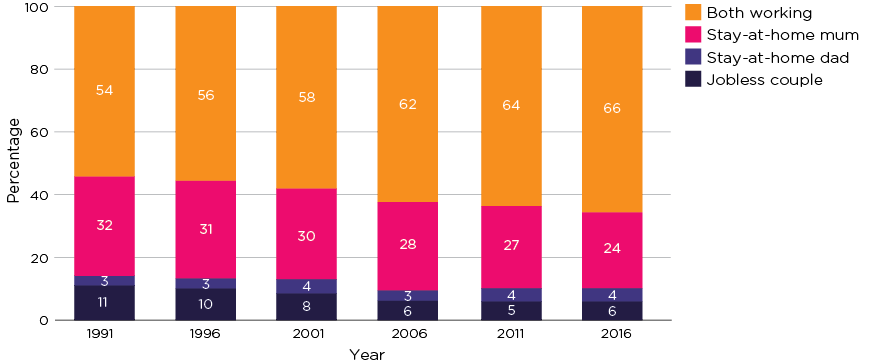

These gendered employment patterns are apparent also in statistics on employment participation, which show that over time, an increasing number of couple families feature two working parents, with fewer comprising a working father and stay-at-home mother (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Couple parent employment patterns 1991–2016

Note: ‘Stay-at-home’ parents are those who are not in work who have a partner/spouse who is in work. ‘Jobless’ families are those in which both parents are not working, including those away from work. ‘Both working’ indicates both parents spent at least one hour in paid work in the reference period. Excludes families in which either parent’s labour force status was not stated. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: Australian Population Census customised reports, 1991–2016

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2019 (aifs.gov.au/copyright)

While there have been changes in family-level employment patterns, fathers’ employment rates are just as high now as they were some decades ago. In fact, higher percentages of fathers were employed in each of 2006, 2011 and 2016 compared to earlier years, reflecting to some extent past economic conditions.

Figure 3 shows the trends in fathers’ employment, for couple and single fathers. For couple fathers, the vast majority are in full-time work. In Australia, fathers may request to work part-time hours, as a flexible work option, to assist in the care of children. However, they rarely do, and instead work in the full-time labour market, in which expectations about long work hours tend to prevail (Smyth et al., 2012). Single fathers have more diverse work patterns with higher proportions in part-time work or not employed. Their higher rates of part-time work and non-employment are unlikely to reflect active choices to spend fewer hours in employment.

Figure 3: Trends in fathers’ employment, couple and single fathers, 1991–2016

Note: Away from work includes those classified as employed but with work hours of zero or not stated.

Source: Australian Population Census customised reports, 1991–2016

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2019 (aifs.gov.au/copyright)

Fathers’ work arrangements

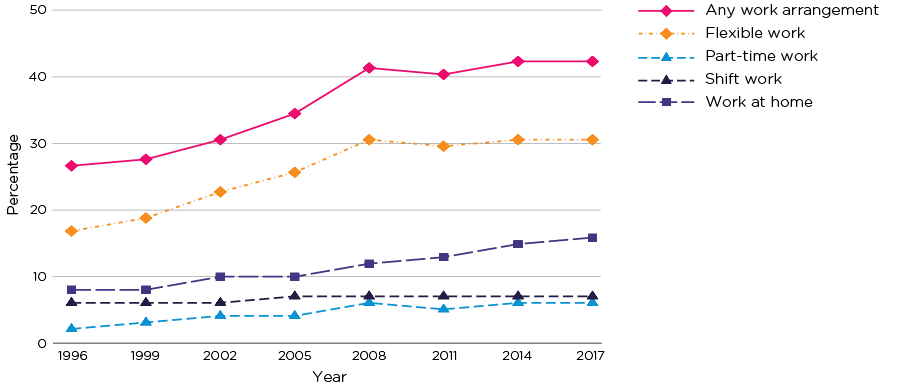

The relatively low uptake of part-time work by fathers, as a means of helping to care for children, is evident in Figure 4, below, which shows the proportion of fathers reported to use any work arrangement to care for children, for 1996 through to 2017. While there was steady growth in the proportion using some work arrangement to care for children from 1996 through to 2008, this has levelled off since this time. The most common arrangement for fathers is flexible work, and this has not changed since 2008. The next most common arrangement for fathers is working at home, and this is the one arrangement that has continued to increase. As seen here, very few fathers are reported to work part-time in order to care for children.

Figure 4: Fathers’ work arrangements used to care for children, 1996–2017

Note: Estimates are for employed parents with children aged under 12 years.

Source: ABS Childhood Education and Care, various years

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2019 (aifs.gov.au/copyright)

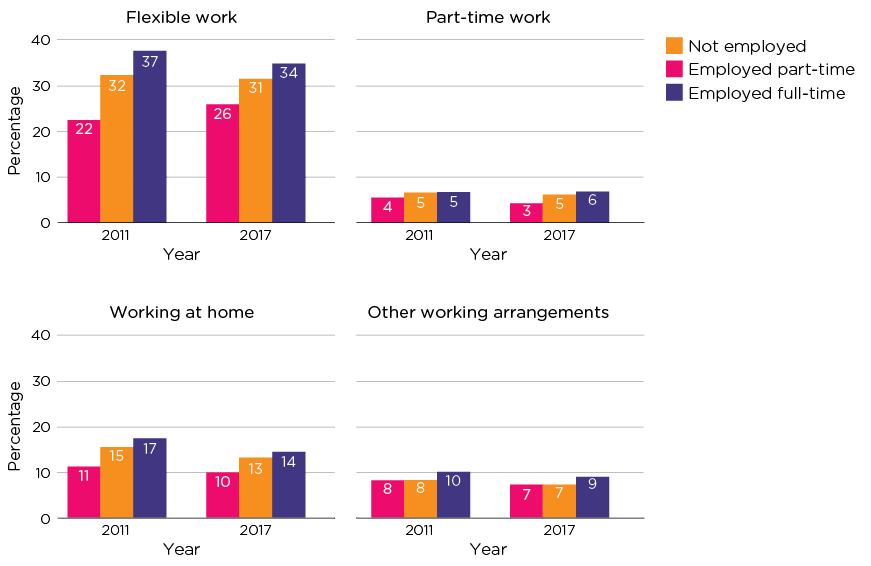

Taking this back to a family perspective, we do find that when mothers work full-time, fathers more often use their own work arrangements to help care for the children. This is particularly evident in relation to flexible work, which is much more likely in families where mothers work full-time compared to those where mothers are not employed (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Fathers’ working arrangements by mother's employment category, 2011 and 2017

Note: Estimates are for employed parents with children aged under 12 years.

Source: ABS Childhood Education and Care, 2011 and 2017, derived from Tablebuilder

Credit: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2019 (aifs.gov.au/copyright)

References

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79(1), 191–228.

Craig, L., Mullan, K., & Blaxland, M. (2010). Parenthood, policy and work–family time in Australia 1992–2006. Work, Employment & Society, 24(1), 27–45.

Pocock, B. (2005). Work/care regimes: Institutions, culture and behaviour and the Australian case. Gender, Work & Organization, 12(1), 32–49.

Sayer, L. C. (2005). Gender, time and inequality: Trends in women’s and men’s paid work, unpaid work and free time. Social Forces, 84(1), 285–303.

Smyth, B. M., Baxter, J. A., Fletcher, R. J., & Moloney, L. J. (2012). Fathers in Australia: A contemporary snapshot. In D. W. Shwalb, B. J. Shwalb & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Fathers in cultural context (pp. 361–382). New York: Routledge.

Dr Jennifer Baxter is a Senior Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies. This article is based on a presentation ‘Trends in fathers’ working arrangements’ given at the AIFS 2018 Conference.

Featured image: © GettyImages/kohei_hara