In Home Care evaluation

Findings from the Child Care Package evaluation

October 2022

Download Research snapshot

Overview

This snapshot presents findings from the 2018–2021 evaluation of the Australian Government's Child Care Package.

The revised In Home Care (IHC) program was introduced on 2 July 2018 as part of the Child Care Package, replacing the previous IHC program and the Nanny Pilot Programme. The revised IHC program aims to support families' workforce participation by providing access to early childhood education and care (ECEC) where other approved child care services are not available or suitable.

This snapshot summarises some of the key findings from the IHC evaluation. The evaluation drew on a range of data including interviews with IHC Support Agencies, IHC Services and other stakeholders, survey data from families, educators and services, and administrative data about the use of IHC.

IHC eligibility

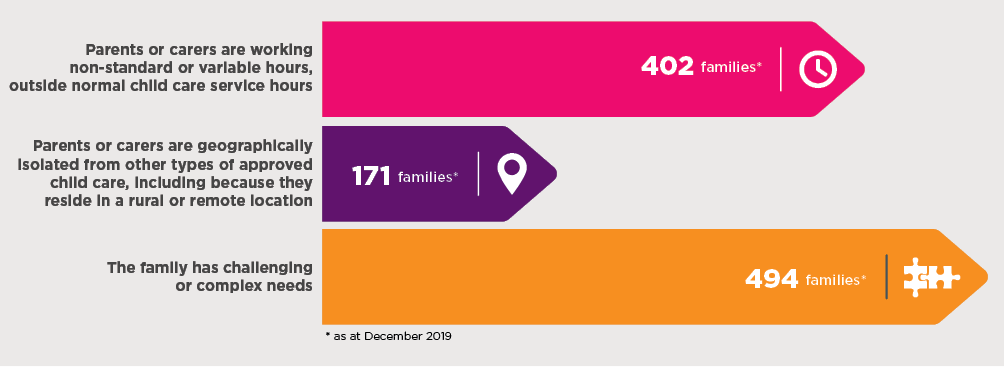

To be eligible for IHC, families must be eligible for the Child Care Subsidy (CCS), and demonstrate that mainstream child care services are not currently suitable or available. They must also meet at least one of the following criteria:

Family satisfaction with IHC and access to IHC

In the Family Survey, conducted for the evaluation in early 2019 and again in late 2019-early 2020, families reported on their satisfaction with IHC and how well IHC was meeting their needs.

- In both waves, most said that IHC meets their needs 'very well/completely' (36% in wave 1 and 38% in wave 2) or 'well' (29% in wave 1 and 32% in wave 2).

- In both waves of the survey, the majority of families were satisfied or very satisfied with how easy it was to get an IHC place (60% in wave 1 and 58% in wave 2), while 29-30% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied, and the rest gave a more neutral response. This reflects some challenges in accessing IHC, with a key challenge being educator availability (discussed further below).

- Satisfaction was high in relation to IHC educator qualities. For example, families rated their satisfaction with educator qualifications or experience, the activities the educator does with the children, and the other activities the educator does with the family. On each item, most (between 80% and 90%) said they were very satisfied or satisfied. Between 2% and 8% rated any of these as dissatisfied or very dissatisfied.

- Families were least satisfied with the out-of-pocket cost of IHC. More than one in 3 (36%) were either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the costs in wave 2. But some families reported satisfaction with the cost, considering it necessary and worth the money.

Some families who meet the eligibility criteria for IHC have been unable to access IHC. According to data compiled by the IHC Support Agencies, in December 2019 there were 518 families (1,088 children) on the waiting list. Reasons for being on the waiting list are coded by the IHC Support Agencies. Two in 3 families (64%) were on the waiting list due to a suitable educator not being available, while 29% were awaiting referral of services or family decisions, and 8% were for other reasons.

IHC is focused on early childhood education and care

The revised IHC program includes a renewed focus on the requirement that IHC is for ECEC, and not for other activities. Most of those interviewed and surveyed for the evaluation thought this was a positive development. However, according to services and educators, the boundaries between 'early childhood education and care' and other activities (in particular, disability care) are not always clear.

The focus on ECEC led to concerns among some services and stakeholders about gaps in service provision for children, particularly those children (or families) with additional or complex needs, whose care needs may not be met by IHC or the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) (see IHC Support Agencies). The concerns were less apparent in interviews held early 2020 compared to those held a year earlier. Some families wish educators could do tasks beyond those covered by the IHC National Guidelines, but keeping the focus on ECEC tasks is largely handled through processes including educators' completion of program diaries (and service review of these), service in-home checks on activities, educator training, induction programs and ongoing professional development.

IHC and mainstream care

One of the elements of the revised IHC program is a renewed focus on IHC provision being temporary. According to the Family Survey, there is a strong sense that families do not see IHC as temporary, and many report having barriers to using mainstream care (see infographic below). For example, in wave 2:

- 79% of families agreed or strongly agreed with 'we need IHC as a long-term arrangement'.

- 16% agreed or strongly agreed with 'my children are likely to move from IHC to other arrangements in the next 6 months'.

- 22% agreed or strongly agreed they were actively looking for mainstream care options.

Of children using IHC in a week, about 20% also use mainstream care at some time during the week. This indicates that IHC is filling gaps in ECEC when mainstream care is not available. Further, there are transitions off IHC into only mainstream ECEC for some children over time, particularly for those that have been able to use mainstream ECEC at the same time as using IHC.

The potential for children to transition to mainstream ECEC is discussed between IHC Support Agencies and families, documented in the Family Management Plan and revisited during its quarterly review. Many of the surveyed families indicated not understanding the Family Management Plan review process that checks in on potential mainstream options, particularly when family circumstances or availability of mainstream options are unlikely to change.

IHC service and educator issues

In late 2019, there were 53 services providing IHC. At this time, there were about 1,869 registered IHC educators but analysis of administrative data indicates that the number of IHC educators providing ECEC to families was about half this number.

Educator qualifications and educator availability

Educator recruitment challenges were apparent through the evaluation. For example, of the 22 services responding to wave 2 of the Services Survey, almost 3 out of 4 services agreed or strongly agreed that they find it difficult to recruit new educators. Families also expressed difficulties with educator availability.

Under the revised IHC program, educators are required to be qualified (or studying toward), at a minimum, a Certificate III in Early Childhood Education and Care. This requirement is to support the renewed focus on providing only early childhood education and care. But the key constraint on the IHC program is the lack of availability of appropriately qualified educators. While the new qualification requirement was generally seen as a positive step by the sector for improving quality of care, more than 2 in 3 IHC services (16 out of 23) surveyed (in wave 2, November 2019-February 2020) said the requirement had had a negative impact. This largely related to the shortage of educators and its impact on the delivery of IHC.

The nature of IHC work also makes educator recruitment challenging as it requires educators to work in remote areas, work at non-standard or variable hours, or work with complex or challenging family circumstances. Some families are seeking access to short shifts of IHC, sometimes split shifts (e.g. before and after school hours). These shifts are not always appealing to educators looking for full-time work.

A significant issue for the supply of IHC is the means of recruiting educators. In particular, families faced challenges when they were asked by a service to find an educator themselves, so that educator could be signed up to deliver their IHC through the service. This occurred sometimes when services engage educators as contractors (rather than employees). Some families reported not feeling equipped to do this recruitment.

Educator income

There was concern among services that the hourly rate cap limits what educators can be paid. This concern was alleviated considerably by the increase to the rate cap in January 2019. Concerns remained, however, about how appropriate the level of the cap is for IHC where penalty rates would apply; that is when working outside standard hours.

The IHC hourly rate cap is also applied at the family, rather than child, level. This was subject to some criticism by educators and services, as it was felt that it was unfair that the same hourly rate cap applied regardless of how many children educators were caring for (up to the maximum allowed). But analysis indicated that hourly fees were no higher in large families than smaller families, suggesting that having a family rate cap is no more likely to affect large families than smaller ones.

Service financial viability

When surveyed late 2019-early 2020, about half of the responding IHC services indicated they were concerned about their service's financial viability. This was apparent through other evaluation data collections, indicating the IHC sector is a particularly vulnerable one.

IHC Support Agencies

Roles of IHC Support Agencies

IHC Support Agencies were introduced for each state and territory. Their key role is to advocate for families, taking on a brokerage role to match families to IHC services after determining their eligibility for IHC. Generally, views indicate that there were advantages to this brokerage model. In interviews in the IHC Program Study, IHC Support Agencies, key stakeholders and several IHC service directors indicated support for the role of IHC Support Agencies in being able to take a broader view of IHC service use at a state or territory level.

The introduction of IHC Support Agencies has been somewhat challenging for IHC services, given these changes have meant they have less control over recruiting families to their service. This was particularly so during the early transition to the revised program.

Some uncertainty about the roles and responsibilities of IHC Support Agencies remains, with families and educators often misunderstanding the differences between IHC Support Agencies and IHC services. This can mean some confusion among educators and families about where to go for support.

Matching services and educators to family care needs

The matching of families to services is done by IHC Support Agencies first communicating with families about their IHC eligibility and completing a Family Management Plan. There is then a process of determining whether the family can be matched to an IHC service, through knowledge of service characteristics and waiting lists. Improvements to this matching process were reported but there were mixed views at the service level about the usefulness and completeness of the Family Management Plans. Further, a small number of services reported concerns about how these processes contributed to delays in the provision of IHC.

Linking children to other support services

The IHC Support Agency role includes connecting families to other services as appropriate. IHC Support Agencies reported in interviews in early 2020 that they were working with colleagues and other local services to find appropriate supports for families who were not eligible for IHC or who would benefit from additional early intervention services. This included connecting families to mainstream ECEC through support from the Inclusion Support Program, as well as to other child and family services where appropriate.

There has been a lack of clarity about how the NDIS and IHC complement each other, and families as well as IHC services and IHC Support Agencies have found the intersection between NDIS and IHC to be unclear and difficult to navigate. This has no doubt been affected by the rollout of the NDIS happening at the same time as the introduction of the revised IHC program.

SUPPLEMENT: Families' use and cost of IHC

Numbers of children and families using IHC

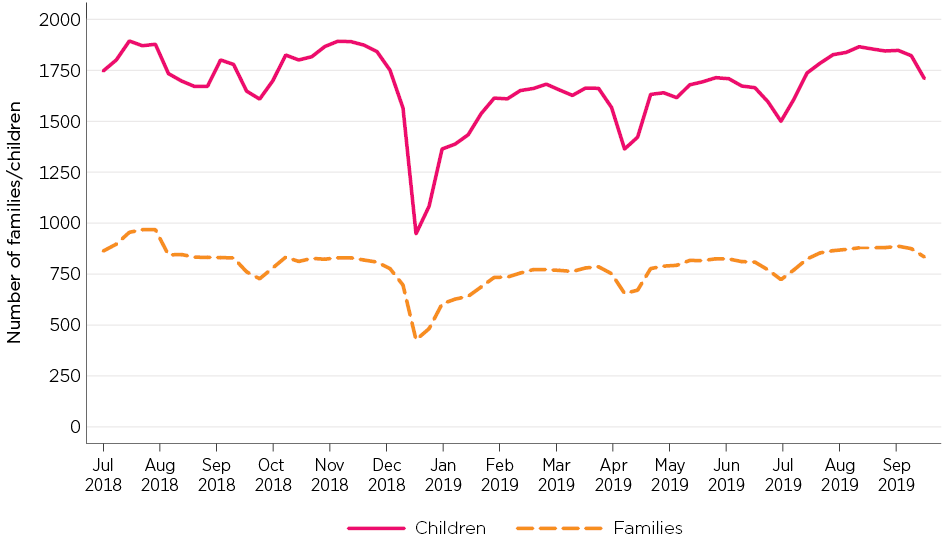

Each week around 800 families and 1,800 children access IHC. This number fluctuates over the year, as does the number of families in other types of approved ECEC (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of families and children using IHC each week, July 2018 to September 2019

Note: This is based on the number who reported any hours of IHC used each week.

Source: Derived from child care administrative data, July 2018 to September 2019

The program is capped at 3,200 'places'. 1 Each full-time place represents 35 hours of subsidised care per child per week or part thereof.

Average hours and time of day

The number of hours of subsidised IHC a family can access is determined by the IHC Support Agencies and cannot exceed the amount of subsidised care a family can access according to their CCS family activity test result. Families using IHC reported in the Families Surveys that they used an average of 29 hours a week of IHC. These surveys were conducted in February-March 2019 (wave 1) and December 2019-February 2020 (wave 2). The average hours families reported using varied by suitability criteria. In 2020:

- geographically isolated families used 43 hours a week on average

- families with complex or challenging needs used 28 hours a week on average

- families with non-standard hours used 20 hours per week.

Families were using fewer hours, on average, than they had been using prior to the introduction of the revised program. According to the Families Survey responses, the cost of care was a factor for families reducing their hours of IHC. However, 8 out of 10 families surveyed in 2020 were satisfied or very satisfied with the number of hours they could access.

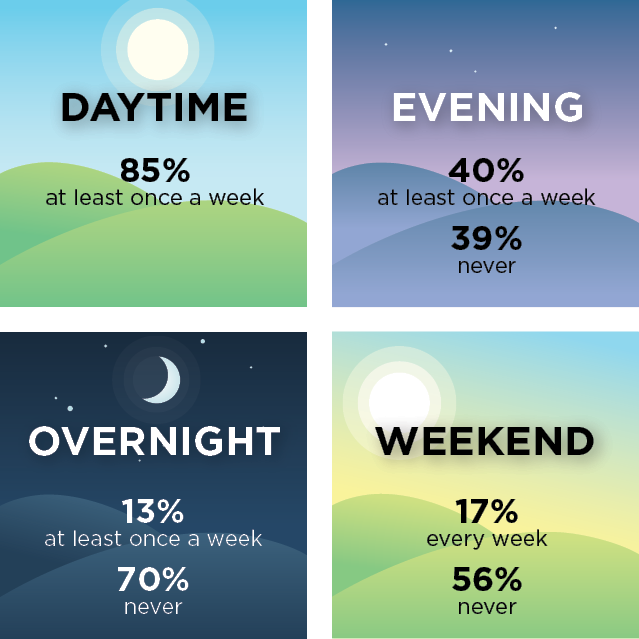

Survey data confirmed that most IHC is regularly provided during the daytime.

In the Family Survey (wave 2), families were asked how often they used IHC at different times of day:

IHC cost

The cost to families is dependent on how much IHC families use, the fees charged by services (relative to the family hourly rate cap), and families' eligibility for CCS and the Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS). For IHC:

- The Child Care Subsidy is on a per family (not per child) basis and was capped, as of 1 January 2019, at $32.00 per hour. If eligible for ACCS, the potential subsidy is $38.40 per hour.

- In the first 6 months of the program, the hourly rate cap for IHC was $25.48 per hour for CCS and $30.58 for ACCS.

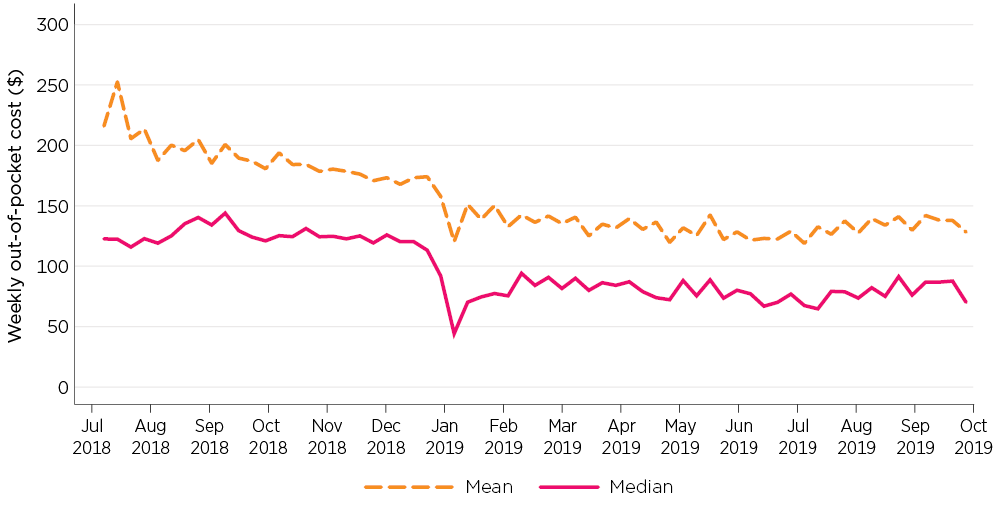

There is variation in experiences of affordability and cost across families. A high proportion of IHC families are on ACCS (28% of the families using IHC in September 2019) and, for them, their IHC costs are very low or nothing. The range of costs is shown in Figure 2. In short:

- One in 4 families using IHC in September 2019 had no out-of-pocket costs.

- One in 2 families were paying between zero and $200 per week.

- One in 4 families were paying above $200.

The changes brought in with the Child Care Package were expected to affect the costs of IHC for families, particularly those not eligible for ACCS. According to administrative data, at September 2019 (the most recent data available at time of reporting), the average weekly cost to all families using IHC was about $165, compared to $118 in September 2017 with the previous program.

According to the survey data, some families had reduced their use of IHC because costs were not affordable. Other survey data indicated that in the transition to the program, some did not continue with the revised program because it was not affordable.

Figure 2: Mean and median family IHC out of pocket costs, June 2018 to September 2019

Note: Out-of-pocket costs are calculated by subtracting the subsidy received from fees charged. The hourly rate cap was increased in January 2019, consistent with the drop in out-of-pocket costs.

Source: Derived from child care administrative data, July 2018 to September 2019

The fee charged by the IHC service, relative to the hourly rate cap, contributes significantly to affordability, as it determines the amount of family co-contribution. The increase in the rate cap in January 2019 meant a decrease in families' average IHC costs, with the updated rate cap better aligned to the average fee charged, leaving a lower gap fee.

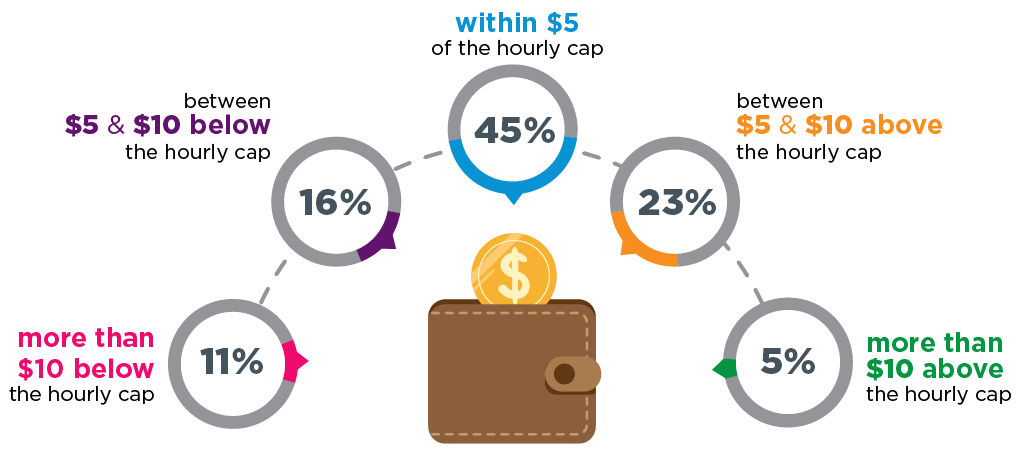

Comparing the hourly fees families were charged to the hourly rate cap for the September quarter 2019:

Child Care Package evaluation

In July 2018 the Australian Government introduced the Child Care Package. The Australian Institute of Family Studies in association with the Social Research Centre, the UNSW Social Policy Research Centre and the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods were commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment to undertake an independent evaluation of the new Child Care Package. Findings presented here are based on data collected and analysed for the Child Care Package evaluation. The evaluation commenced in December 2017 prior to the introduction of the Package and reported on data collected up to December 2019. The evaluation was impacted by external events, particularly COVID-19, which resulted in the suspension of the child care funding system for a period during 2020. As a result, the evaluation only draws on data to the end of 2019 and does not include data from 2020.

1 The number of places increased from 3,000 places to 3,200 in January 2019.

Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2022). The 2018–2021 Child Care Package: In Home Care evaluation. (Findings from the Child Care Package evaluation). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.