Factors influencing therapy use following a disclosure of child sexual abuse

June 2021

James Herbert

Download Policy and practice paper

Overview

Identifying consistent factors that influence engagement or completion of therapy across studies allows services and policy makers in criminal justice, child protection, community support and mental health systems to make informed decisions about approaches to therapy referral and how to support families through challenges they have that could affect their capacity to engage with services. This paper presents findings from a review of the literature aimed at identifying factors that may influence either engagement with therapy or the completion of therapy following a disclosure of child sexual abuse to authorities. The lack of Australian studies highlights the need for local research on factors influencing therapy use to help inform the design of referral systems and interventions to improve the use of available therapy services.

This paper reports on the results of a rapid evidence review of research into the factors that influence the utilisation of therapy for child sexual abuse. This review is also described in the companion paper Rates of Therapy Use Following a Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse.

Appendix A describes the search strategy used in the review and Appendix B outlines the characteristics of the included studies.

Key messages

-

Few factors consistently influenced engagement and completion - particularly for clinical studies reporting completion rates.

-

Higher rates of engagement and completion appear to be associated with more severe abuse experiences - increased symptomatology (a set of symptoms) at intake seemed to increase completion rates among community samples.

-

Family-level factors (e.g. parental attitudes about therapy) seemed to most consistently affect engagement rates.

-

Parental involvement in therapy was one of the most consistent determinants of therapy completion, highlighting the importance of therapy models including a clear role for caregivers.

-

Services and systems should monitor their own data on risk factors for disengagement and withdrawal to inform strategies to manage attrition.

Introduction

Despite efforts to make services available to address the effects of abuse, affected children and families often have significant barriers that limit their capacity to engage with therapy. These barriers can include service-level barriers, such as difficulty finding the right service provider and qualifying for therapy under a particular funding scheme. Families with a disclosure of child sexual abuse may also have multiple complex issues such as homelessness, poverty, family and domestic violence, and alcohol and substance abuse issues that can present additional barriers to accessing services. These barriers reduce the proportion of affected children that may engage with and benefit from therapy services.

Commonly, informal systems of referral assume that children have a protective parent who is in a position to be able to advocate for and seek services for them. The lack of a planned system of referral at the point of disclosure means there is limited knowledge of the extent of the barriers that may exist for children and families to engage with therapy.

This review examines the factors that influence rates of engagement and completion of therapy following a disclosure of child sexual abuse to police or child protection authorities. In this paper, therapy refers to any program of therapy intended to reduce the effects of trauma following abuse. The type of therapy in each of the included studies is described in Appendix B. By identifying the factors that consistently, and across many studies, influence engagement or completion, this research aims to inform approaches to support and to increase engagement and completion of therapy.

Methodology

This paper reports on the results of the rapid evidence review described in the companion paper Rates of Therapy Use Following a Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse. Appendix A provides an overview of the search strategy and extraction process that included studies examining the effects of abuse, child, perpetrator, family and response characteristics on engagement and completion of therapy. All studies included in the review of rates were examined by a single reviewer to identify whether studies looked at the effect1 of any factors on rates of engagement or completion. This information was then included in the extraction template, separating out factors that significantly2 affected engagement/completion (and the direction of the difference), and factors that were not associated with a significant difference.

Included studies were split across those reporting rates of engagement following contact with police or child protection authorities (investigation samples; see below for definitions), or those where children or families had contacted sexual abuse therapy services (therapy initiators). Completion studies were split between clinical samples (which had inclusion/exclusion criteria for eligibility) and community samples (where services were provided to any children without having to meet inclusion/exclusion criteria).

Sample types included in the review

Engagement samples - studies that used engagement with therapy, meaning attendance at the first session of therapy, as a dependent variable:

- Investigation samples - studies where factors influencing rates of engagement were examined for children following an investigation by authorities.

- Therapy initiator samples - studies where factors influencing rates of engagement were examined for children who presented to specialist sexual abuse therapy service providers.

Completion samples - studies that used completion of therapy, which was measured in terms of the completion of therapy elements, a minimum number of sessions, or discharge from therapy, as a dependent variable.

- Clinical samples - studies where samples were required to demonstrate clinically significant3 symptoms and tended to have exclusion criteria (i.e. ongoing domestic violence, parental mental health issues).

- Community samples - studies where samples were composed of all children that presented for a service from a specialist child sexual abuse therapy provider.

1 In this context the effect of factors on rates of engagement or completion refers to whether a factor was found to influence engagement or completion rates through some form of statistical testing.

2 Significance in this context refers to statistical significance, meaning that the analysis has found an effect that passes a threshold that suggests the result is not attributable to chance.

3 'Clinically significant symptoms' is distinct from the concept of statistical significance and refers to a score on a standardised instrument (e.g. Child Behaviour Checklist) that suggests the presence of some diagnosable issue or disorder.

What are the findings of this review?

Generally, included studies were testing one of two quite different hypothesised arguments for why therapy engagement and completion rates varied. The first was that families with more complexity, with children that had longer histories of abuse, and parents with fewer economic and social resources would be more likely to drop out or not engage with therapy. The second was that families that were more supportive of their children, with more social resources, and where the abuse was a single incident and not part of a trajectory of persistent abuse may not engage or complete services out of concerns about stigmatising children or a sense that 'getting back to normal' may be the most appropriate way to support their children. The framing of the research questions in these studies differed considerably depending on the context of the research, and the types of samples these hypotheses were tested in.

1. Engagement with therapy factors

Key findings

- More severe instances of abuse seem to be associated with increased engagement among post-investigation samples.

- Some family characteristics were found to affect engagement, particularly among investigation samples: parental attitudes about the child; parental attitudes about therapy and perceived need for therapy; number of children in the household; and parental supportiveness at a forensic interview.

- Few significant differences were found among therapy initiator samples.

This section reviews five groupings of characteristics, which were examined in the studies for their effect on engagement: abuse, child, perpetrator, family and response characteristics (see Appendix A for inclusions); and includes two types of samples: post-investigation (studies that examined rates of commencing therapy following a police/child protection investigative response), and therapy initiator (studies examining rates of commencing therapy following a child/family making contact with service providers to obtain therapy for children/young people affected by sexual abuse).

Nine of the 49 selected studies examined factors that may influence the rate of engagement with therapy. The rate of engagement with therapy can be defined as commencing therapy (attending at least one session) in all but one study, where it was defined as attending three sessions (Deblinger, Stauffer, & Steer, 2001).

Abuse characteristics

Overall, abuse characteristics seemed to have a mild effect on engagement. Across five individual studies, four out of 11 comparisons of abuse characteristics on engagement with therapy were found to be significant; however, the direction of the findings (i.e. whether the factor was associated with an increase or decrease in engagement) was mixed, making it difficult to draw conclusions across study contexts. The findings seem to suggest that more complex abuse (e.g. more severe, more frequent, co-occurring neglect) was associated with increased engagement with therapy. Table 1 provides an overview of the abuse comparisons.

Among post-investigation samples, Anderson (2016) found that more severe abuse (i.e. penetrative contact offences vs non-penetrative contact offences) was associated with higher rates of engagement, although three other studies found no significant differences. Tingus, Heger, Foy, and Leskin (1996) found that children with abuse that involved multiple incidents (compared to single incidents) were more likely to engage, although two other studies found no difference. Cases in which neglect co-occurred with sexual abuse were found to be much more likely to engage, which was attributed to the effect of child protection safety plans that required parents to engage with therapy to retain care of their children (Lippert, Favre, Alexander, & Cross, 2008).

For therapy initiator samples, only one study tested whether different abuse characteristics influenced engagement (Oates, O'Toole, Lynch, Stern, & Cooney, 1994). Contrary to Tingus and colleagues (1996), they found that children with abuse that involved a single incident were more likely to engage than children with multiple incidents of abuse.

| Abuse characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of effects | Studies | |

| Investigation | ||||

| Severity of abuse | 1 | 3 | More severe abuse - more likely to engage | Anderson (2016), Lippert et al. (2008), McPherson et al. (2012), Tingus et al. (1996) |

| Number of incidents | 1 | 2 | Repeated incident - more likely to engage | Lippert et al. (2008), McPherson et al. (2012), Tingus et al. (1996) |

| Co-occurring neglect | 1 | Co-occurring neglect - more likely to engage | Lippert et al. (2008) | |

| Duration of abuse | 1 | Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Therapy Initiators | ||||

| Severity of abuse | 1 | Oates et al. (1994) | ||

| Number of incidents | 1 | Single incident - more likely to engage | Oates et al. (1994) | |

Child characteristics

Child characteristics for the most part did not affect engagement. Across six individual studies, the only significant effects found were differences in the rate at which white children in the United States engaged with therapy relative to minority groups (see Table 2). Three studies found white children were significantly more likely to engage with therapy than black and Latino/Latina/Hispanic children in the United States.

| Child characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of effects | Studies | |

| Investigation | ||||

| Ethnicity | 3 | 1 | White children - more likely to engage White children - more likely to engage White children - more likely to engage | Haskett et al. (1991), Lippert et al. (2008), McPherson et al. (2012), Tingus et al. (1996) |

| Gender | 2 | Haskett et al. (1991), McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Child mental health or disability | 2 | Anderson (2016), Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Age | 1 | Haskett et al. (1991) | ||

| Therapy initiators | ||||

| Ethnicity | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2001) | ||

| Age | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2001) | ||

| Gender | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2001) | ||

Perpetrator characteristics

Perpetrator characteristics also for the most part did not affect engagement (see Table 3). Oates and colleagues (1994) found a significant difference among therapy initiator samples in terms of the relationship with the perpetrator. Abuse by family members and extra-familial adults in regular contact were both found to be associated with an increased likelihood of engaging with therapy compared to perpetrators who did not have regular contact with the child. In contrast, four studies with post-investigation samples found no effect for the relationship to the perpetrator.

| Perpetrator characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of effects | Studies | |

| Investigation | ||||

| Relationship to perpetrator | 4 | Anderson (2016), Haskett et al. (1991), Lippert et al. (2008), Tingus et al. (1996) | ||

| Age of perpetrator | 2 | Allen et al. (2014), Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Gender of perpetrator | 1 | Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Ethnicity of perpetrator | 1 | Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Therapy initiators | ||||

| Relationship to perpetrator | 1 | Family member (vs person not in regular contact with child) - more likely to engage Extra familial in regular contact with child (vs person not in regular contact with child) - more likely to engage | Oates et al. (1994) | |

Family characteristics

From seven studies, five comparisons of family characteristics were found to be significant across 33 comparisons (see Table 4). Lippert and colleagues (2008) tested a variety of parental attitudes about their child and about therapy in interviews. While most had a non-significant effect, they found that parents who said they 'liked going places with their child' were less likely to engage in therapy. The researchers suggested that this seemed to reflect a tendency towards parent-centredness versus child-centredness among cases that engaged with therapy.

Lippert and colleagues (2008) also found that families that declined therapy were more uncomfortable about disclosing personal information to a therapist, and engagers were more likely to think therapy was for 'emotional help and change'. In a complementary finding, Hasket, Nowlan, Hutcheson, and Whitworth (1991) found that where a maternal caregiver thought the entire family needed therapy, they were more likely to engage.

Anderson (2016) found that parents who were designated as not supportive of their children following a forensic interview (as rated by observers) were nearly 10 times more likely to begin therapy. This may be due to the implied threat of child protection action for caregivers whom authorities could determine are not protective. Self-Brown, Tiwari, Lai, Roby, and Kinnish (2016) found an increased likelihood of engaging with therapy where more children lived in a household.

| Family characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of effects | Studies | |

| Investigation | ||||

| Parental history of abuse | 3 | Haskett et al. (1991), Lippert et al. (2008), McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Maternal belief that abuse occurred | 2 | Haskett et al. (1991), Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Parental education | 2 | Haskett et al. (1991), Self-Brown et al. (2016) | ||

| Parental history of substance abuse | 2 | Haskett et al. (1991), McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Parental attitudes about child | 1 | 1 | 'Like going places with their child' - less likely to engage | Lippert et al. (2008) |

| Parental attitudes about therapy | 1 | 1 | Therapy is for 'emotional help and change' - more likely to engage 'Discomfort disclosing personal information to a therapist' - less likely to engage | Lippert et al. (2008) |

| Abuse/neglect history | 2 | Lippert et al. (2008), McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Parental support | 1 | Designated as unsupportive parents - more likely to engage | Anderson (2016) | |

| Perceived need for family counselling | 1 | Maternal caregiver thought whole family needed counselling - more likely to engage | Haskett et al. (1991) | |

| Marital status | 1 | Haskett et al. (1991) | ||

| Socio-economic status | 1 | Haskett et al. (1991) | ||

| Availability of transport | 1 | Haskett et al. (1991) | ||

| Perceived need for child therapy | 1 | Haskett et al. (1991) | ||

| Parental criminal history | 1 | Haskett et al. (1991) | ||

| Telephone in household | 1 | Haskett et al. (1991) | ||

| Family social capital | 1 | Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Family functioning | 1 | Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Parental history of domestic violence | 1 | McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Number of children in household | 1 | More children in household - more likely to engage | Self-Brown et al. (2016) | |

| Parental age | 1 | Self-Brown et al. (2016) | ||

| Caregiver symptomatology | 1 | Self-Brown et al. (2016) | ||

| Therapy initiators | ||||

| Marital status | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2001) | ||

| Socio-economic status | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2001) | ||

| Parental history of abuse | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2001) | ||

| Number of caregivers | 1 | Oates et al. (1994) | ||

Response characteristics

Only four studies examined factors related to the response to the abuse; however, half of the comparisons were found to be significant in terms of engagement with therapy (see Table 5). Referrals to private practice therapy (Haskett et al., 1991), or additional counselling during or after the initial treatment (McPherson, Scribano, & Stevens, 2012) were found to significantly increase engagement. Tingus and colleagues (1996) found that where children had been removed from the home following their abuse, they were more likely to engage, although McPherson and colleagues (2012) did not find a significant difference on this factor. Tingus and colleagues (1996) also found that where both police and child protection agencies were involved in a case (other conditions were: child protection only and no agency involved), children were more likely to engage with therapy.

| Response characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of effects | Studies | |

| Investigation | ||||

| Referral to private therapy | 1 | Referral to private therapy - more likely to engage | Haskett et al. (1991) | |

| Days from report to therapy | 1 | Lippert et al. (2008) | ||

| Referral to other counselling | 1 | Additional counselling referrals during or after initial treatment - more likely to engage | McPherson et al. (2012) | |

| Child protection determination | 1 | McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Child protection filed for custody | 1 | McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Care arrangements | 1 | 1 | Placement outside the home - more likely to engage | McPherson et al. (2012), Tingus et al. (1995) |

| Investigating agency | 1 | Both police and child protection involvement - more likely to engage | Tingus et al. (1995) | |

2. Completion of therapy factors

Key findings

- Among clinical samples, relatively few factors influenced completion, possibly due to the stricter eligibility criteria.

- Among community samples:

- More severe and more frequent abuse was associated with higher rates of completion.

- Increased symptomatology was generally associated with higher rates of completion, although there were some mixed findings on this.

- Children were less likely to complete therapy when the perpetrator was a non-relative. Higher completion for cases where the perpetrator was a parent or parental figure may be due to the attention of statutory agencies to safety in the home.

- Across both samples, parental involvement in therapy was consistently found to have affected completion; however, family coping, abuse/neglect history in the family and the caregivers' history of abuse did not consistently affect completion.

Twenty-seven studies tested factors that may influence the rate of completion of therapy following a disclosure of sexual abuse. This section reviews five characteristics: abuse, child, perpetrator, family and response (see Appendix A for inclusions); and includes two types of samples: clinical (studies that were limited to children that met criteria of clinical symptomatology), and community (studies including all children that presented for a service). The clinical samples represent studies with more tightly controlled conditions (i.e. procedures to monitor fidelity to the treatment model), usually as the study was undertaken to demonstrate the efficacy of the different therapies in optimal conditions.

The definitions of completion differed across the studies included (see Appendix A). Generally, clinical studies included criteria based on the delivery or completion of a program and the community studies involved a discharge from the service agreed to by the clinician and the client.

Abuse characteristics

Across the 33 comparisons conducted across 16 studies, none of the abuse characteristics were found to affect completion in clinical samples; however, many factors were found to be significant in the community studies (see Table 6). Three studies found that where the abuse included fewer incidents or a single incident, children were less likely to complete therapy (Chasson, 2007; Chasson, Mychailyszyn, Vincent, & Harris, 2013; Deblinger, Lippmann, & Steer, 1996). Findings were consistent for the effect of abuse severity on completion, with four studies finding that more severe abuse was associated with increased completion (Chasson, 2007; Chasson et al., 2013; Horowitz, Putnam, Noll, & Trickett, 1997; Mogge, 1999), although six other studies found no difference. Two studies found that longer abuse duration was associated with completion, although two other studies found no difference on this factor.

The direction of findings was mixed for the age of onset of abuse, with Horowitz and colleagues (1997) finding that earlier onset (i.e. age of the child when the abuse began) was associated with completion and Tavkar (2010) finding earlier onset was associated with dropping out of therapy.

| Abuse characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of significant effects | Studies | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Abuse frequency | 4 | Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Cohen et al. (2004), King et al. (2000) | ||

| Abuse severity | 4 | Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Cohen et al. (2004), King et al. (2000) | ||

| Age of onset of abuse | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Community | ||||

| Abuse severity | 4 | 6 | No life threat or injury - less likely to complete Higher severity - more likely to complete Less severe - less likely to complete No life threat or physical injury - less likely to complete | Chasson et al. (2013), Horowitz et al. (1997), McPherson et al. (2012), Mogge (1999), New & Berliner (2000), Reyes (1996), Tavkar (2010), Chasson (2007), Deblinger et al. (1996), Barnett (2007) |

| Abuse frequency | 3 | 2 | Single incident - less likely to complete Fewer incidents - less likely to complete Single trauma - less likely to complete Less traumas - more likely to complete | Chasson et al. (2013), McPherson et al. (2012), Chasson (2007), Deblinger et al. (1996), Barnett (2007), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a |

| Abuse duration | 2 | 2 | Shorter duration - less likely to complete Longer duration - more likely to complete | Friedrich et al. (1992), Mogge (1999), New & Berliner (2000), Tavkar (2010) |

| Age of onset of abuse | 2 | Earlier onset - more likely to complete Earlier onset - less likely to complete | Horowitz et al. (1997), Tavkar (2010) | |

| Type of victimisation | 1 | Chasson et al. (2013) | ||

| Time from abuse to disclosure | 1 | Tavkar (2010) | ||

| Disclosure | 1 | Tavkar (2010) | ||

| Co-occurring abuse or neglect | 1 | Barnett (2007) | ||

Note: The reference Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) included two sets of analyses, which have been included separately on the comparison tables. Instances marked with an 'a' refer to the analysis based on clinician rated dropout.

Child characteristics

For child characteristics, 69 comparisons were made across 19 studies (see Table 7). For the clinical samples, across the 22 comparisons only one study found a significant difference. Celano, NeMoyer, Stagg, & Scott (2018) found that older children were less likely to complete therapy, although five other studies found no difference. All other comparisons in the clinical samples found no difference in terms of child gender, ethnicity and initial symptomatology.

For the community samples, across the 47 comparisons, a number of studies found significant differences. The effects of initial symptomatology on completion seemed to be mixed, partly due to the different definitions of completion. This may be because of the converse effects of: (a) children with more intense behavioural issues and trauma (based on psychometric instruments) being less likely to complete due to difficulty in getting them to sessions; (b) children with less severe trauma symptoms being less likely to complete due to parental concerns about stigmatising children. Five out of 16 studies found significant differences for rate of completion in terms of initial symptomatology.

Horowitz and colleagues (1997) and New and Berliner (2000) found that more severe symptoms were generally associated with higher rates of completion, whereas Barnett (2007) and Wamser-Nanney and Steinzor (2017) found the opposite. Tebbett (2013) found that moderate scores on the internalising problems subscale and high and low scores on the externalising problems subscale of the Parental Rating Scale Behavioral Assessment System for Children was associated with higher rates of completion. Barnett (2007) found that higher scores on the Social Behaviour Index (indicating a child's social competency) was associated with higher rates of completion. Barnett (2007) also found that on the Expectations Test (used to measure hypervigilance and expectations of future harm) that children who expected sexual abuse in their future were less likely to complete therapy, whereas children that did not know what to expect or had positive expectations were more likely to complete. Nine studies found no difference for rate of completion in terms of children's initial symptomatology.

In the community sample, Chasson, Vincent, and Harris (2008) measured symptomatology before termination (measures were completed bi-weekly during treatment) and found avoidance behaviour (measured on the Impact of Event Scale) was associated with dropout. Barnett (2007) also included some mid-treatment measures and found that a client's perceived improvement in symptoms was associated with completion.

Most of the community studies found no difference in terms of child age, gender or ethnicity, although Wamser-Nanney and Steinzor (2017) found that (in a United States context) minorities were less likely to complete, and New and Berliner (2000) found that younger children were more likely to complete.

| Child characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of significant effects | Studies | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Child age | 1 | 5 | Older children - less likely to complete | Celano et al. (2018), Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Cohen et al. (2004), Deblinger et al. (1996), King et al. (2000) |

| Child gender | 6 | Celano et al. (2018), Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Cohen et al. (2004), Deblinger et al. (1996), King et al. (2000) | ||

| Child ethnicity | 6 | Celano et al. (2018), Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Cohen et al. (2004), Deblinger et al. (1996), King et al. (2000) | ||

| Initial symptomatology | 4 | Celano et al. (2018), Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Deblinger et al. (1996) | ||

| Community | ||||

| Initial symptomotology | 5 | 9 | Higher scores on Child Depression Index & Child Behavior Checklist Aggressive/Delinquent Subscale - more likely to complete Presence of PTSD - more likely to complete Rule-breaking behaviour & aggressive behaviour on Child Behavior Checklist - less likely to complete Higher score on Child Behavior Checklist - less likely to complete Higher score on internalising Child Behavior Checklist - less likely to complete Higher score on externalising Child Behavior Checklist - less likely to complete Moderate scores on internalising problems, Parental Rating Scale Behavioral Assessment System for Children - more likely to complete High and low scores on externalising problems, Parental Rating Scale Behavioral Assessment System for Children - more likely to complete Higher scores on Social Behaviour Inventory - more likely to complete Sexual abuse indicated on Expectations Test - less likely to complete Don't know or positive indicated on Expectations Test - more likely to complete | Barnett (2007), Chasson et al. (2008), Chasson et al. (2013), Horowitz et al. (1997), Macias (2004), Mogge (1999), New & Berliner (2000), Reyes (1996), Tavkar (2010), Tebbett (2013), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b |

| Child ethnicity | 1 | 9 | Minority status - less likely to complete | Barnett (2007), Horowitz et al. (1997), Marx (2004), McPherson et al. (2012), Mogge (1999), New & Berliner (2000), Reyes (1996), Tavkar (2010), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b, |

| Child gender | 9 | Barnett (2007), Marx (2004), McPherson et al. (2012), Mogge (1999), New & Berliner (2000), Reyes (1996), Tavkar (2010), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b, | ||

| Child age | 1 | 7 | Younger children - more likely to complete | Barnett (2007), Chasson et al. (2013), Horowitz et al. (1997), Mogge (1999), New & Berliner (2000), Tavkar (2010), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b |

| Mid-treatment symptomotology | 2 | 1 | Higher avoidance behaviours on the Impact of Event Scale - less likely to complete Improvements in symptomology - more likely to complete | Barnett (2007), Chasson et al. (2008) |

| Child attributions of abuse | 1 | Reyes (1996) | ||

| Therapist's prognosis | 1 | New & Berliner (2000) | ||

| Combined gender & ethnicity | 1 | Marx (2004) | ||

Notes: The reference Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) included two sets of analyses, which have been included separately on the comparison tables. Instances marked with an 'a' refer to the analysis based on clinician rated dropout. Instances of Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) marked with a 'b' refer to the analysis based on completion of a minimum number of sessions (i.e. 12).

Perpetrator characteristics

The studies reviewed included 13 comparisons of perpetrator characteristics across 11 studies (see Table 8). Across the clinical studies, none of the comparisons were significant. Among community studies, around half found that the relationship to the perpetrator affected the rate of completion. The findings were generally consistent in showing that abuse by non-relatives was associated with lower rates of completion than abuse by a parent or parental figure (Chasson et al., 2013; Mogge, 1999; New & Berliner, 2000). Three other studies found no difference in rates of completion based on the relationship to perpetrator (Chasson, 2007; Reyes, 1996; Tavkar, 2010). Mogge (1999) found that where perpetrators remained in the home, children were less likely to complete therapy.

| Perpetrator characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of significant effects | Studies | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Relationship to perpetrator | 4 | Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Cohen et al. (2004), Deblinger et al. (1996), King et al. (2000) | ||

| How perpetrator engaged child | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Community | ||||

| Relationship to perpetrator | 3 | 3 | Older child - less likely to complete Stranger or non-relative - less likely to complete Parent or parental figure - more likely to complete | Chasson (2007), Chasson et al. (2013), Mogge (1999), New & Berliner (2000), Reyes (1996), Tavkar (2010) |

| Perpetrator remains in home | 1 | Perpetrator remains in home - less likely to complete | Mogge (1999) | |

| Number of perpetrators | 1 | Barnett (2007) | ||

Family characteristics

Across 65 comparisons in 19 studies, 13 comparisons of family characteristics were found to influence completion rates (see Table 9). The most consistent result was the effect of parental attendance/engagement with therapy; all studies that included this as a variable found that increased parental involvement was associated with increased completion (Celano et al., 2018; Macias, 2004; McPherson et al., 2012).

Two studies (one clinical study and one community study) found that higher socio-economic status increased completion rates (Cohen & Mannarino, 1996; Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor, 2017); however, another seven studies found no difference. One out of four comparisons found that higher parental education positively influenced completion rates (Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor, 2017 - clinician-rated completion).

Nine studies measured family coping at intake in a variety of ways; however, only one study found that this affected rates of completion (Tavkar, 2010). Tavkar (2010) found higher parental distress, resentment associated with role as a parent, and the ability to identify behavioural and problem-solving strategies were all associated with lower rates of completion. However, two community studies looking at a parent's PTSD symptoms and psychopathology symptoms found no effect on completion rates (Self-Brown et al., 2016; Tebbett, 2013).

Single studies found that the absence of child protection history (Wamsner-Nanney & Steinzor, 2017) and lower rates of parental reported domestic violence (DeLorenzi, Daire, & Bloom, 2016) were associated with higher rates of completion. Out of four community studies that tested the effect of parental history of sexual abuse on completion rates, only Macias (2004) identified an effect and only among mothers who had an abuse history and perpetrated the abuse on their child.

Across the community studies, parental age (Tavkar, 2010), therapist ratings of caregiver support (Barnett, 2007), and participation in the therapy process (a therapist-rated checklist of the therapy process across both parents and children; Barnett, 2007) all had single comparisons that supported the influence of these factors on completion.

| Family characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of significant effects | Studies | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Socio-economic status | 1 | 3 | Lower status - less likely to complete | Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000), Cohen et al. (2004), King et al. (2000) |

| Carer characteristics | 3 | Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen et al. (2004), King et al. (2000) | ||

| Family coping | 2 | Cohen & Mannarino (1996), Cohen & Mannarino (2000) | ||

| Primary caregiver therapy attendance | 1 | Increased attendance - more likely to complete | Celano et al. (2018) | |

| Care arrangements | 1 | Cohen & Mannarino (1996) | ||

| Parental age | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Parental marital status | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Parental employment status | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Parental psychotropic medication use | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Parental substance abuse | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Parental history of sexual abuse | 1 | Cohen et al. (2004) | ||

| Parental practices | 1 | Delinger et al. (1996) | ||

| Community | ||||

| Family coping | 1 | 6 | Higher score on Symptom Checklist 90 Revised - less likely to complete Higher score on Parenting Stress Index - less likely to complete Lower score on the Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scales - less likely to complete | Horowitz et al. (1997), Macias (2004), Marx (2004), Tavkar (2010), Tebbett (2013) |

| Socio-economic status | 1 | 4 | Higher status - more likely to complete | Horowitz et al. (1997), McPherson et al. (2012), Tavkar (2010), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b |

| Parental education | 1 | 3 | Higher maternal education - more likely to complete Higher paternal education - more likely to complete | Self-Brown et al. (2016), Tavkar (2010), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b |

| Number of children in the same residence | 3 | McPherson et al. (2012), Self-Brown et al. (2016), Tavkar (2010) | ||

| Parental marital status | 3 | Tavkar (2010), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b | ||

| Parental history of sexual abuse | 1 | 3 | Mothers who were abused and who perpetrated the abuse - less likely to complete | McPherson et al. (2012), Mogge (1999), Tavkar (2010), Macias (2004) |

| Family child protection history | 1 | 2 | No history - more likely to complete | McPherson et al. (2012), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b |

| Primary caregiver therapy attendance | 2 | Maternal participation in therapy - more likely to complete Parental participation - more likely to complete | Macias (2004), McPherson et al. (2012) | |

| Parental history of domestic violence | 1 | 1 | Higher exposure to parental domestic violence - less likely to complete History of domestic violence - less likely to complete | DeLorenzi et al. (2016), McPherson et al. (2012), Barnett (2007) |

| Parental age | 1 | 1 | Older parents - more likely to complete | Self-Brown et al. (2016), Tavkar (2010) |

| Parental symptomotology | 2 | Self-Brown et al. (2016), Tebbett (2013) | ||

| Carer characteristics | 2 | Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b | ||

| Caregiver support | 1 | Higher therapist ratings of caregiver support - more likely to complete | Barnett (2007) | |

| Participation in therapy process | 1 | More completion of therapy process variables - more likely to complete | Barnett (2007) | |

| Parental substance abuse | 1 | McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Insurance status | 1 | New & Berliner (2000) | ||

| Parent gender | 1 | Tavkar (2010) | ||

| Parent ethnicity | 1 | Tavkar (2010) | ||

| Parental employment status | 1 | Tavkar (2010) | ||

| Parental expectations | 1 | Tavkar (2010) | ||

Notes: The reference Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) included two sets of analyses, which have been included separately on the comparison tables. Instances marked with an 'a' refer to the analysis based on clinician rated dropout. Instances of Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) marked with a 'b' refer to the analysis based on completion of a minimum number of sessions (i.e. 12).

Response characteristics

Only four of 17 comparisons of response characteristics found a significant effect (see Table 10). Cohen, Mannarino, and Knudsen (2005) found higher rates of dropout for non-structured supportive therapy compared with trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy. Celano and colleagues (2018) found that more assessment/diagnostic sessions at the start of therapy could result in higher dropout. Newman and Berliner (2000) found that delays to commencing therapy resulted in reduced dropout. McPherson, Scribano, and Steinzor (2012) found that referrals to other counselling services during or after the initial therapy was associated with higher rates of completion.

| Response characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | Direction of significant effects | Studies | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Treatment type | 1 | 1 | Non-structured supportive therapy - less likely to complete | Cohen et al. (2005), King et al. (2000) |

| Number of diagnostic evaluation sessions | 1 | Fewer diagnostic sessions - more likely to complete | Celano et al. (2018) | |

| Treatment duration | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2011) | ||

| Trauma narrative | 1 | Deblinger et al. (2011) | ||

| Community | ||||

| Time to therapy | 1 | 2 | Longer delay between time of crime to beginning therapy - more likely to complete | New & Berliner (2000), Tavkar (2010) |

| Child protection disposition | 2 | McPherson et al. (2012) | ||

| Child in foster care at time of evaluation | 2 | McPherson et al. (2012), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b | ||

| Therapist characteristics | 2 | New & Berliner (2000), Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b | ||

| Therapist and client ethnicity match | 1 | Koch (2004) | ||

| Referrals to other services | 1 | Referrals to other counselling services - more likely to complete | McPherson et al. (2012) | |

| Miles from clinic | 1 | Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)a, Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017)b | ||

Notes: The reference Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) included two sets of analyses, which have been included separately on the comparison tables. Instances marked with an 'a' refer to the analysis based on clinician rated dropout. Instances of Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) marked with a 'b' refer to the analysis based on completion of a minimum number of sessions (i.e. 12).

Limitations to these findings

This review is limited in being able to draw conclusions on the effect of many factors due to the limited number of studies examining their effects on the engagement and completion of therapy. The number of different types of samples (e.g. investigation vs therapy initiators) in the included studies further limited the number of comparisons available. The review has focused on discussing findings where there appeared to be similar findings across multiple comparisons/studies.

The literature search was undertaken across the most common databases for social sciences and criminal justice research and included a pearling strategy to identify additional relevant studies (see Appendix A for more detail on the pearling strategy). However, a full registered systematic review could identify additional eligible studies. In addition, the search string included the term 'counselling', which may have limited the results by not including other variants on the word (e.g. counsellor, counseling).

Common to many evidence reviews, the studies identified in the search were overwhelmingly conducted in the United States (n = 45; 92%), with the other four studies conducted in Australia. While some caution should be taken in generalising the findings to other contexts, it is worth noting the diversity of approaches and resources across US states for responding to child sexual abuse (e.g. Herbert, Walsh, & Bromfield, 2018).

An important limitation of this review is that engagement and completion of therapy do not necessarily indicate improved outcomes for children and their families. While completion of an indicated service is important to the likelihood of obtaining benefits from the therapy, many other factors will influence the likelihood of reduced symptomology such as the effectiveness of the treatment model and the fidelity of the therapy to effective treatment models.

What are the implications for policy and practice?

Key findings

- Many of the comparisons across studies of engagement and completion were mixed, with most non-significant and many in opposite directions. This suggests services and systems should monitor their own data on risk factors for disengagement and withdrawal to inform strategies to manage attrition.

- Most consistently, parental involvement in therapy was found to be associated with increased completion of therapy, suggesting that targeting efforts to increase parental motivation may be a productive way to improve completion.

- More severe and frequent abuse was associated with increased completion of therapy. This plus the inconsistency of completion findings about symptoms at intake suggest there may be a cohort with less severe/frequent abuse that are experiencing trauma symptoms that are at risk of withdrawing from therapy.

The findings of this review were mixed with few clear and consistent findings across studies, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the key factors that impact therapy engagement and completion across contexts. The mix of findings points to the complex nature of these outcomes, how different contexts change the influence of these factors, and the interactive effects between different types of variables. Most consistently, two factors stood out:

- Increased parental involvement in therapy was found to be associated with increased therapy completion (Barnett, 2007; Celano et al., 2018; Macias, 2004; McPherson, Scribano, & Stevens, 2012). Therapy models delivered to this population of children should incorporate a clear role for parents/caregivers. The presence of a parent/caregiver willing to be involved should be part of the therapy triage process, and resources should be put into attempting to build parent/caregiver's motivation to be involved (Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010).

- More severe and frequent abuse was associated with increased therapy completion (Chasson, 2007; Chasson et al., 2013; Deblinger, Lippmann, & Steer, 1996; Horowitz et al., 1997; Mogge, 1999). This combined with less consistent findings in terms of symptomology suggests children with trauma symptoms associated with less severe/frequent abuse may be at increased risk of not completing therapy. Monitoring symptoms and discussing progress on formal instruments may be a way to address the risk of these children not completing therapy.

Systematic monitoring of the needs and characteristics of children and families disclosing abuse to authorities is critical to addressing the barriers to access and maximising opportunities for earlier intervention in the management of trauma from sexual abuse. The complexity of findings across the included studies means that it is difficult to recommend factors that should be screened, monitored and controlled in the administration of therapy following a disclosure of child sexual abuse. However, this review highlights factors that service providers can consider monitoring to help develop strategies to inform approaches to referral and support at the point of disclosure depending on their service populations (see Appendix A). These strategies may focus on the service level, such as identifying ways to improve the client experience of referral or instituting a holding service while clients are on a waitlist.

Alternatively, strategies may focus on barriers within the family and on the motivation/hesitancy to engage with therapy among caregivers, as well as involve broader support and advocacy or even additional interventions to help stabilise families (e.g. Safecare®). Emerging evidence suggests that strategies addressing parental hesitancy about mental health services paired with strategies to streamline the referral, assessment, and waitlist for services can improve engagement and completion (Budde & Waters, 2014). Building motivation to engage with therapy through structured psycho-educational approaches seems particularly important for children who may not have trauma symptoms straight away.

References

- Allen, B., & Hoskowitz, N. A. (2017). Structured trauma-focused CBT and unstructured play/experiential techniques in the treatment of sexually abused children: A field study with practicing clinicians. Child Maltreatment, 22(2), 112-120.

- Allen, B., Tellez, A., Wevodau, A., Woods, C. L., & Percosky, A. (2014). The impact of sexual abuse committed by a child on mental health in adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(12), 2257-2272.

- Ancha, A. J. (2003). Program evaluation of a time-limited, abuse-focused treatment for child and adolescent sexual abuse victims and their families (Psy.D.). Argosy University MI, Ann Arbor, United States.

- Anderson, G. D. (2016). Service outcomes following disclosure of child sexual abuse during forensic interviews: An exploratory study. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10(5), 477-494.

- Barnett, C. W. (2007). Predicting treatment completion with maltreated children. PhD thesis. The University of Utah, Salt Lake City UT, United States.

- Budde, S. & Waters, J. (2014). PATHH: Improving access and quality of mental health services to sexually abused children in Chicago. Chicago, IL: Chicago Children's Advocacy Center. Retrieved from www.chicagocac.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/ChicagoCAC-PATHH-White-Paper-102414.pdf

- Celano, M., NeMoyer, A., Stagg, A., & Scott, N. (2018). Predictors of treatment completion for families referred to trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy after child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(3), 454-459.

- Chasson, G. S. (2007). Survival analysis of treatment attrition with child victims of trauma: The role of trauma severity. PhD thesis. University of Houston, Houston TX, United States.

- Chasson, G. S., Mychailyszyn, M. P., Vincent, J. P., & Harris, G. E. (2013). Evaluation of trauma characteristics as predictors of attrition from cognitive-behavioral therapy for child victims of violence. Psychological Reports, 113(3), 734-753.

- Chasson, G. S., Vincent, J. P., & Harris, G. E. (2008). The use of symptom severity measured just before termination to predict child treatment dropout. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(97), 891-904.

- Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., & Steer, R. (2004). A multi-site, randomized controlled trial for children with abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 393-402.

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1996). Factors that mediate treatment outcome of sexually abused preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(1), 1402-1410.

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1997). A treatment study for sexually abused preschool children: Outcome during a one-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(9), 1228-1235

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (2000). Predictors of treatment outcome in sexually abused children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(7), 983-994.

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Knudsen, K. (2005). Treating sexually abused children: 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(2), 135-145.

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Perel, J. M., & Staron, V. (2007). A pilot randomized controlled trial of combined trauma-focused CBT and sertraline for childhood PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(7), 811-819.

- Cross, T. P., Jones, L. M., Walsh, W. A., Simone, M., & Kolko, D., Sczepanski, J. et al. (2008). Evaluating children's advocacy centres' response to child sexual abuse. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, 106, 1-11.

- Deblinger, E., Lippmann, J., & Steer, R. (1996). Sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms: Initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreatment, 1(4), 310-321.

- Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Runyon, M. K., & Steer, R. A. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 67-75.

- Deblinger, E., Stauffer, L. B., & Steer, R. A. (2001). Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for young children who have been sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreatment, 6(4), 332-343.

- DeLorenzi, L., Daire, A. P., & Bloom, Z. D. (2016). Predicting treatment attrition for child sexual abuse victims: The role of child trauma and co-occurring caregiver intimate partner violence. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 7(1), 40-52.

- Fong, H. F., Alegria, M., Bair-Merritt, M. H., & Beardslee, W. (2018). Factors associated with mental health services referrals for children investigated by child welfare. Child Abuse and Neglect, 79, 401-412.

- Friedrich, W. N., Luecke, W. J., Beilke, R. L., & Place, V. (1992). Psychotherapy outcome of sexually abused boys: An agency study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 7(3), 396-409.

- Garland, A. F., Landsverk, J. L., Hough, R. L., & Ellis-MacLeod, E. (1996). Type of maltreatment as a predictor of mental health service use for children in foster care. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20(8), 675-688.

- Hartman, S. (2011). From efficacy to effectiveness: A look at trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy in a community setting (Psy.D.). Pace University, Ann Arbor, MI

- Haskett, M. E., Nowlan, N. P., Hutcheson, J. S., & Whitworth, J. M. (1991). Factors associated with successful entry into therapy in child sexual abuse cases. Child Abuse & Neglect, 15(4), 467-476.

- Herbert, J. L., Walsh, W., & Bromfield, L. M. (2018). A national survey of characteristics of child advocacy centers in the United States: Do the flagship models match those in broader practice? Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 583-595.

- Horowitz, L. A., Putnam, F. W., Noll, J. G., & Trickett, P. K. (1997). Factors affecting utilization of treatment services by sexually abused girls. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(1), 35-48.

- Humphreys, C. (1995). Whatever happened on the way to counselling? Hurdles in the interagency environment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 19(7), 801-809.

- King, N. J., Tonge, B. J., Mullen, P., Myerson, N., Heyne, D., Rollings, S. et al. (2000). Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(11), 1347-1355.

- Koch, E. R. (2004). Factors associated with treatment outcomes among Hispanic survivors of childhood sexual abuse. PhD thesis. Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena CA, United States.

- Lane, W. G., Dubowitz, H., & Harrington, D. (2003). Child sexual abuse evaluations: Adherence to recommendations, Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 11(4), 17-34.

- Lippert, T., Favre, T., Alexander, C., & Cross, T. P. (2008). Families who begin versus decline therapy for children who are sexually abused. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 859-868.

- Lundahl, B. W., Kunz, C., Brownell, C., Tollefson, D., & Burke, B. L. (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20, 137-160.

- Macias, S. B. (2004). The intergenerational transmission of abuse: The relationship between maternal abuse history, parenting stress, child symptomatology, and treatment attrition. PhD thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara, United States.

- Marx, T. (2004). Attrition from childhood sexual abuse treatment as a function of gender, ethnicity, and parental stress PhD thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara CA, United States.

- McPherson, P., Scribano, P., & Stevens, J. (2012). Barriers to successful treatment completion in child sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(1), 23-29.

- Mogge, K. L. (1999). Predictors of dropout in child sexual abuse treatment. PhD thesis. University of Memphis, Memphis TN, United States.

- Murphy, R. A., Sink, H. E., Ake, G. S., Carmondy, K. A., Amaya-Jackson, L. M., & Briggs, E. C. (2014). Predictors of treatment completion in a sample of youth who have experienced physical or sexual trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(1), 3-19.

- New, M., & Berliner, L. (2000). Mental health service utilization by victims of crime. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(4), 693-707.

- Oates, R. K., O'Toole, B. I., Lynch, D. L., Stern, A., & Cooney, G. (1994). Stability and change in outcomes for sexually abused children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(7), 945-953.

- Reyes, C. J. (1996). Resiliency of young children: Self-concept, parental support, and traumatic symptoms after sexual abuse. PhD thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara CA, United States.

- Self-Brown, S., Tiwari, A., Lai, B., Roby, S., & Kinnish, K. (2016). Impact of caregiver factors on youth service utilization of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy in a community setting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1871-1879.

- Signal, T., Taylor, N., Prentice, K., McDade, M., & Burke, K. J. (2017). Going to the dogs: A quasi-experimental assessment of animal assisted therapy for children who have experienced abuse. Applied Developmental Science, 21(2), 81-93.

- Smith, D. W., Witte, T. H., & Fricker-Elhai, A. E. (2006). Service outcomes in physical and sexual abuse cases: A comparison of child advocacy center-based and standard services. Child Maltreatment, 11(4), 354-360.

- Tavkar, P. (2010). Psychological and support characteristics of parents of child sexual abuse victims: Relationship with child functioning and treatment. PhD thesis. The University of Nebraska, Lincoln NE, United States.

- Tebbett, A. A. (2013). Predictors of attrition in trauma-specific cognitive-behavioral therapy. PhD thesis. St. John's University, New York NY, United States.

- Tingus, K. D., Heger, A. H., Foy, D. W., & Leskin, G. A. (1996). Factors associated with entry into therapy in children evaluated for sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(1), 63-68.

- Wamser-Nanney, R., & Steinzor, C. E. (2017). Factors related to attrition from trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect, 66, 73-83.

- Zaidi, L. Y., & Gutierrez-Kovner, V. M. (1995). Group treatment of sexually abused latency-age girls. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10(2), 215-227.

Appendix A: Therapy use

Search strategy

A search string was generated using the NVIVO auto-code feature with full text extracted from 15 target studies; this was used to identify key terms likely to identify other relevant studies (see Box A.1). The search string4 was run across Psychinfo, Embase, Medline, Proquest Social Science Premium Collection, and Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global. The results were screened in Covidence by title and abstract, and then by full record.

Box A.1 Search string

((treat* or mental health or mental-health or therap* or service* or counselling) and (child* or youth or young pe* or girls or boys) and (sexual abus* or molest* or sexual assault or exploit or sexual harm or sexual maltreat*) and (utilis* or utiliz* or complet* or engag* or attend* or obstacle* or attrition or access* or hinder* or motivation* or enrol* or drop* or exit* or cessat* or quit* or leave* or end*) and (factors or barriers or enabl* or characteris* or cause* or component* or influenc* or aspect* or impediment* or obstacle* or facilitate* or predict* or pattern* or determin*)).ab.

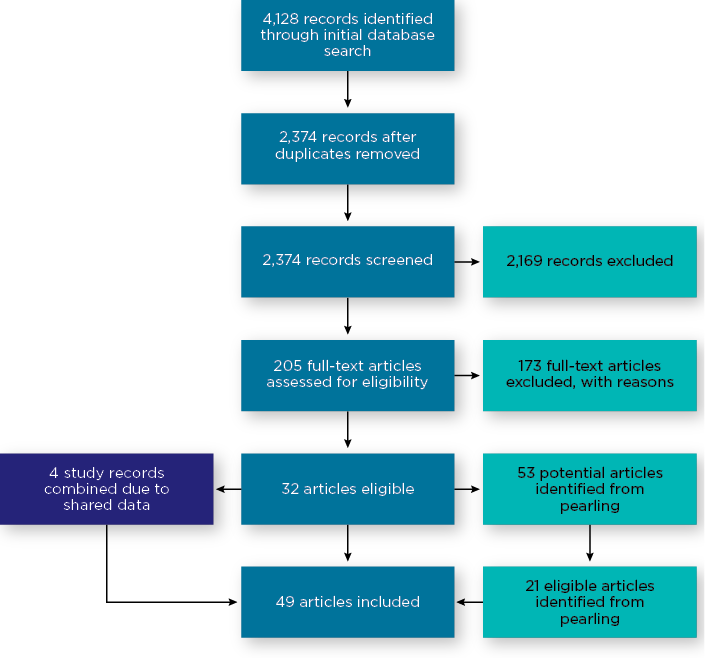

The search identified 2,374 individual studies for title and abstract screening, which was reduced to 205 studies by a single reviewer for full-text screening (see Figure A.1). These were studies that very clearly did not meet eligibility based on title and abstract. These 205 studies were assessed for eligibility, which identified 32 eligible studies. A total of 173 studies were excluded for the following reasons:

- The study was about the impacts of abuse rather than referral/engagement/completion of therapy (n = 42).

- The study involved an adult population (n = 32).

- The study design did not allow for data about referral/engagement/completion (n = 18).

- Sexual abuse was not analysed separately from other forms of maltreatment (n = 15).

- Study was about the characteristics or impacts of abuse rather than about the treatment of abuse (n = 12).

- The paper did not involve empirical research and was a conceptual or theoretical paper (n = 8).

- Full text could not be obtained, even when requested from the University of South Australia library services (n = 7).

- Other/miscellaneous (n = 11).

Pearling5 was undertaken across the 32 eligible studies. This involved reading through each of the articles and identifying any references to studies that may contain relevant information for the review. This process identified an additional 21 eligible studies. Some of the eligible studies (n = 4) were found to be an analysis of the same dataset. In these cases, information about the studies was combined into a single record in the extraction template. A total of 49 studies were found to be eligible and were extracted.

Figure A.1: PRIMSA flow diagram of systematic literature search

The extraction template included:

- study information: study ID number, authors, year, if the study shared data with any other included studies, title, country of study, publication type, study design

- sample information: sample type narrative description, whether caregiver consent to participate in the study was required, whether clinical symptoms were required to be included, whether the sample initiated therapy, if the sample was from a children's advocacy centre, if cases were required to be substantiated to be included, if a mixed abuse sample then what proportion included sexual abuse, if mixed age groups then what proportion was under 18, gender, ethnicity

- therapy characteristics: therapy narrative description, if caregivers were part of the therapy, definition of referral, definition of engagement, definition of completion

- data: total sample, referral data, engagement data, completion data

- independent variable narrative: significant differences, non-significant differences.

Five studies had relevant data on rates of referral, 19 studies had relevant data on rates of engagement, and 37 studies had relevant data on rates of completion of services. The reported rates for groups of studies are based on pooled proportions using a random effects proportional meta-analysis conducted in MedCalc (see below for meta-analysis methodology).

This research was undertaken to identify typical rates of referral, engagement and completion across different types of therapy services for children disclosing sexual abuse. The intent of this was to illustrate the typical proportions of children that are not benefiting from or not receiving the full benefit of therapeutic services to address harm from sexual abuse. We note that many survivors access therapy later in life; however, intervening early is critical to reducing the effects of trauma and the impacts of abuse across life domains.

Meta-analysis

Multiple proportional meta-analyses were conducted on the included studies to produce the pooled rates reported. Each of the rates was grouped based on characteristics that seemed likely to affect the referral/engagement/completion rates.

For referral rates, studies were grouped on whether they required cases to have been substantiated by authorities (i.e. police, child protection or some other authority), or whether abuse was suspected and still subject to investigation.

For engagement rates, studies were grouped into post-investigation - self and professional referral, post-investigation - specified professional referral, and therapy initiators. Two other groupings of studies were found that have been reported on (observational studies and children in care) but were not included as meta-analyses due to small numbers and these studies not being as relevant to the central questions of service access following disclosure. Post-investigation - self and professional referral refers to studies that examined engagement with therapy following an investigation regardless of whether a referral was made for a child. Post-investigation - specified professional referral refers to studies examining engagement related to a specific referral made by police, child protection or some other professional following an investigation. Therapy initiators refers to studies examining the rate of engagement for clients that have contacted specialist sexual abuse services; for these studies it generally is not known who made the referral.

For completion rates studies were grouped into either clinical samples, which required clinically significant symptomology to be included, or community samples, where services responded to clients regardless of if they met the threshold for clinically significant symptomatology. Clinical samples also tended to deliver a structured program of therapy as part of efforts to test the effectiveness of treatment, which also included screening out clients that may have ongoing issues in the home such as parental mental health, family and domestic violence, or parental substance abuse.

The proportional meta-analysis feature in MedCalc was used, reporting on the results of the random effects model, reflecting that the studies were heterogeneous in that rates were likely to be affected by the characteristics of the studies and samples. Publication bias testing was performed in Statsdirect 3.

The results of each of the meta-analyses are reported in Table A.1. The funnel plots for each of the tests are available from the author on request.

| Pooled sample | Test for heterogeneity | Random effects [95% confidence interval] | Publication bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral rates | ||||

| Suspected abuse | 1,678 | Q = 8.74, df = 2, p = 0.013* | 47% [39-56] | Egger's test, p = <0.05 I2 = 77.1% |

| Substantiated abuse | 172 | Q = 0.75, df = 1, p = 0.385 | 79% [72-85] | Egger's test, p = <0.05 I2 = 0% |

| Engagement rates | ||||

| Post investigation - self and professional referral | 423 | Q = 4.08, df = 1, p = 0.043* | 30% [22-40] | Egger's test, p = <0.05 I2 = 75.5% |

| Post investigation - specified professional referral | 1,417 | Q = 35.77, df = 6, p = <0.0001* | 61% [54-68] | Egger's test, p = 0.952 I2 = 83.2% |

| Therapy initiators | 795 | Q = 119.79, df = 7, p = <0.0001* | 81% [68-91] | Egger's test, p = 0.154 I2 = 94.2% |

| Completion rates | ||||

| Clinical samples | 1,499 | Q = 73.025, df = 11, p = <0.0001* | 73% [67-79] | Egger's test, p = 0.662 I2 = 80.6% |

| Community samples | 3,992 | Q = 301.83, df = 26, p = <0.0001* | 59% [54-65] | Egger's test, p = 0.662 I2 = 91.3% |

Note: * p = <.05

4 The search string is a standard format of search terms - using a search string is important so that potentially someone can run the same search and arrive at the same result.

5 Pearling involves searching the reference list of included studies to identify any additional relevant studies that may not have been identified in the initial search.

Appendix B: Therapy use

| Author(s) | Country | Sample6 | Therapy type/s | Study design | Data included in reviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen & Hoskowitz (2017) | United States | 420 | TF-CBTa vs play/experiential therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion |

| Allen et al. (2014) | United States | 117 | Unspecified ('mental health services, therapy or treatment') | Retrospective study of college students that had experienced sexual abuse | Rate of engagement Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) |

| Ancha (2003) | United States | 57 | Abuse-focused cognitive behavioural therapy | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion |

| Anderson (2014; 2016)7 | United States | 139 | Unspecified ('counselling') | Study of service use following a forensic interview | Rate of engagement Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| Arata (1998) | United States | 204 | Unspecified ('counselling' and 'therapy') | Study of current wellbeing of CSA survivors | Rate of engagement |

| Barnett (2007) | United States | 945 | Unspecified ('mental health treatment') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Celano et al. (2018) | United States | 77 | TF-CBT | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Chasson (2007) | United States | 90 | Combination of cognitive behavioral and supportive therapy | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) |

| Chasson et al. (2008; 2013) | United States | 134 | Exposure-based CBTb | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) |

| Chasson, Vincent, & Harris (2008) | United States | 99 | Combination of cognitive behavioral and supportive therapy | Study of whether symptom severity can predict attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen & Mannarino (1996)8 | United States | 86 | CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Study of factors influencing treatment outcomes | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen & Mannarino (1997) | United States | 86 | CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion |

| Cohen & Mannarino (2000) | United States | 82 | CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen et al. (2004) | United States | 229 | TF-CBT vs child-centred therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Cohen et al. (2007) | United States | 24 | TF-CBT with sertraline vs TF-CBT with placebo | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion |

| Cohen, Mannarino, & Knudsen (2005) | United States | 82 | TF-CBT vs non-directive supportive therapy | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Cross et al. (2008) | United States | 1452 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of referral Rate of engagement |

| Deblinger et al. (2011) | United States | 210 | TF-CBT without trauma narrative vs TF-CBT with trauma narrative | Outcomes comparison | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Deblinger, Lippmann, & Steer (1996) | United States | 100 | CBT vs standard community care | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Deblinger, Stauffer, & Steer (2001) | United States | 67 | CBT vs supportive counselling | Outcomes comparison | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Child characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| DeLorenzi, Daire, & Bloom (2016) | United States | 107 | Unspecified ('counselling') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Fong et al. (2018) | United States | 160 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Sub-set of national (US) dataset on referral to therapy | Rate of referral |

| Friedrich et al. (1992) | United States | 42 | Open-ended therapy with directive and non-directive components | Outcomes study | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) |

| Garland et al. (1996) | United States | 75 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement |

| Hartman (2011) | United States | 24 | TF-CBT | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion |

| Haskett et al. (1991) | United States | 129 | Unspecified ('crisis counselling') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) |

| Horowitz et al. (1997) | United States | 81 | Unspecified ('treatment services') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Humphreys (1995) | Australia | 155 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of referral Rate of engagement Rate of completion |

| King et al. (2000) | Australia | 46 | CBT vs waitlist | Outcomes comparison | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Koch (2004) | United States | 91 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of factors associated with treatment outcomes | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Lane, Dubowitz, & Harrington (2002) | United States | 66 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of referral Rate of engagement |

| Lippert et al. (2008) | United States | 101 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) |

| Macias (2004) | United States | 85 | Unstructured treatment | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Marx (2004) | United States | 134 | Unstructured treatment | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| McPherson, Scribano, & Stevens (2012) | United States | 490 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Mogge (1999) | United States | 174 | Unspecified ('therapy') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Murphy et al. (2014) | United States | 404 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion |

| New & Berliner (2000) | United States | 608 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Oates et al. (1994) | Australia | 66 | Therapists reported on the type of therapy approaches used | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of engagement Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| Reyes (1996) | United States | 43 | Non-directed play therapy | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) |

| Self-Brown et al. (2016) | United States | 41 | TF-CBT | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Rate of completion Family characteristics (Engagement) |

| Signal et al. (2017) | Australia | 23 | Animal-assisted therapy | Pre-post outcomes | Rate of completion |

| Smith, Witte, & Fricker-Elhai (2006) | United States | 17 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement |

| Tavkar (2010) | United States | 104 | CBT | Study of factors associated with treatment outcomes | Rate of referral Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Perpetrator characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |

| Tebbett (2013) | United States | 104 | TF-CBT | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) |

| Tingus et al. (1995) | United States | 511 | Unspecified ('mental health service') | Study of service uptake | Rate of engagement Abuse characteristics (Engagement) Child characteristics (Engagement) Perpetrator characteristics (Engagement) Response characteristics (Engagement) |

| Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor (2017) | United States | 122 | TF-CBT | Study of attrition from therapy | Rate of completion Abuse characteristics (Completion) Child characteristics (Completion) Family characteristics (Completion) Response characteristics (Completion) |