Parenting programs that support children's mental health through family separation

A common elements analysis

November 2021

Rhys Price-Robertson, Nicole Paterson

Download Policy and practice paper

Summary

One of the most effective ways to safeguard children's mental health through separation is to support their parents in the process. Yet many separating parents receive support from health and welfare practitioners who have limited training in working with separating families. Evidence-based programs for separating families can provide practitioners in diverse sectors with information about 'what works'. This paper identifies the common elements of evidence-based parenting programs that support children's (aged 0-12 years) mental health through parental separation to inform the decisions practitioners make in their practice.

Key messages

-

Prolonged parental conflict can have enduring, negative effects on children's social and emotional wellbeing.

-

Supporting parents to understand the impact of parental separation on children, to engage in effective parenting practices throughout separation, and to develop functional co-parenting relationships can mitigate the negative effects of separation and contribute to better outcomes for children and the family.

-

Evaluations of parenting programs repeatedly show positive impacts on parental and child wellbeing. However, large, manualised programs are impractical for delivery by practitioners working outside of group settings.

-

The 'common elements' approach adopted in this review identifies 15 techniques, strategies and routines that are shared by numerous programs for separating parents.

- Four of the common elements related to the content presented to parents in programs, specifically the topics of emotional management in separation, parenting in separation, co-parenting in separation, and the impact of separation on children.

- The remaining 11 common elements involved specific techniques used in programs, including skills practice, personalising content, assigning and reviewing homework, and normalising difficulties.

-

A common elements approach does not indicate whether particular elements of programs are necessary or sufficient for clinical change.

Introduction

Children can experience multiple and complex reactions to family separation or divorce. For some children, especially those exposed to family violence or child abuse and neglect, separation can be a positive change (Amato, Kane, & James, 2011). For others, the initial period of separation is disruptive but their social and emotional wellbeing gradually returns to states comparable to those of their peers from intact families (Amato, 2010). However, for some children, family separation has enduring negative consequences, particularly in cases of prolonged interparental conflict. There is strong evidence to show that in comparison to children from intact families, children of separated parents are at greater risk of a range of poor outcomes, including academic difficulties, behaviour problems, substance misuse, and severe and persistent mental health difficulties (Amato, 2010; D'Onofrio & Emery, 2019).

In Australia, approximately one in four Australian children experience parental separation before the age of 18 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2010). Research has consistently demonstrated that most of the negative consequences of parental separation for children are not due to the separation per se but rather due to factors that can accompany separation, especially parental acrimony and conflict (Amato, 2010). Therefore, a common and effective way to safeguard children's wellbeing through separation is to support parents in the process (Schramm & Becher, 2020).

The Australian Government provides a range of targeted services for families who are in dispute, separating or separated, including family dispute resolution, family counselling, divorce education programs, co-parenting programs, children's programs and children's contact services (Attorney-General's Department, n.d.). Most of these services are provided through Australia's 65 Family Relationship Centres (FRCs), which are delivered by community-based organisations (e.g. Relationships Australia, Centacare) (Relationships Australia, 2020). Research has demonstrated FRCs' broad effectiveness in reducing the number of referrals to the family courts (Kaspiew et al., 2009). However, many separating families do not access FRCs and there is scope for a broader range of health and welfare practitioners to increase their knowledge and skills in 'what works' in this area of practice.

One challenge to this approach is that practitioners working outside of the family relationships sector have limited formal training in, or organisational support for, working with separating families (Levkovich & Eyal, 2020; Mahony, Walsh, Lunn, & Petriwskyj, 2015). These practitioners potentially play an important role in supporting children's wellbeing through family separation; therefore, training and support are likely to enhance their capacities to work effectively in this complex area.

Since many of the programs offered by FRCs are tailored to the individual needs of families and have not been evaluated, it is useful to consider the peer-reviewed literature on evidence-based programs to identify 'what works'. A program is considered 'evidence-based' when it has been rigorously evaluated, typically by randomised controlled trial (RCT) or quasi-experimental design, and has been found to have a positive effect on one or more relevant outcomes (Axford & Morpeth, 2013). Evidence-based programs are normally manualised, which means that each family receives a broadly consistent intervention. This makes it easier to identify the practices and strategies that they are comprised of.

The common elements analysis conducted as part of this rapid review examines the components of evaluated programs that have been found to work across various settings. It is impractical for practitioners to use large, manualised programs in individual practice settings. A common elements approach gets around this by customising aspects of large programs to individual practice to ensure evidence-informed strategies are used. The rapid review was conducted to inform the design and delivery of resources for professionals and organisations who work with children (aged 0-12 years old) and/or parents/families to have the skills to identify, assess and support children at risk of mental health conditions.

Evidence-based programs for family separation

Evidence-based programs for separating families can be divided into three broad categories that focus on the family members involved: child-focused programs, child and parent focused programs, and parent-focused programs. In most cases these programs are intended to improve outcomes for the children of separating parents.

Research has generally shown positive and fairly long-lasting results for child-focused programs. These often take the form of preventative group programs implemented in schools (for reviews, see Pedro-Carroll, 2005; Poli, Molgora, Marzotto, Facchin, & Cyr, 2017; Rose, 2009) but they are also increasingly being conducted online (e.g. the Children of Divorce-Coping with Divorce program; Boring, Sandler, Tein, Horan, & Vélez, 2015). Evidence-based child and parent focused programs are less common, and often have more of a therapeutic focus. The small body of existing research on these programs suggests they show effectiveness in supporting parent-child relationships and child wellbeing during and after separation (e.g. Child-Parent Relationship Therapy; Dillman Taylor, Purswell, Lindo, Jayne, & Fernando, 2011).

Parent-focused programs, which are the most common form of program for separating families, come in two main forms. The first is divorce education programs. Almost all of the research evidence in this area comes from the United States, where 46 states have policies or legislation requiring separating and divorcing parents of children under 18 years of age to attend a divorce education program that promotes positive parenting, co-parenting and child adjustment (Bowers, Ogolsky, Hughes Jr, & Kanter, 2014). Most of these programs are court-affiliated, universal, didactic and brief, normally lasting between four and 10 hours over one or two sessions (Schramm & Becher, 2020). Evaluations of US-based divorce education programs have demonstrated generally positive outcomes for families, with online and in-person programs showing comparable results (Schramm & McCaulley, 2012).

The second form of parent-focused program is parenting programs designed for separating parents. While these parenting programs may share some similar content with divorce education programs, they are usually longer in duration (commonly spanning multiple sessions over weeks or months), are generally not affiliated with the court system (although in some jurisdictions legal professionals may refer families to them), and have stronger emphases on group work, skills training and therapeutic processes. Again, such programs have generally led to positive outcomes for families (see Appendix B for an overview of the evidence base).

The literature on evidence-based programs for separating families provides Australian health and welfare practitioners with important information about 'what works' to support children's mental health through family separation. However, implementing manualised programs can be challenging for many reasons, including the time required for training, the high costs of program materials, the resource requirements of delivering programs, and a lack of fit between program characteristics and local circumstances (Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005; Mitchell, 2017). Implementing an intensive evidence-based program is simply beyond the scope of many practitioners' professional roles.

The common elements approach

The common elements approach aims to address the challenges of implementing evidence-based programs by isolating the program elements - specific techniques, practices, strategies, and routines - that are shared by numerous interventions in a particular area of practice (Chorpita et al., 2005; Garland, Hawley, Brookman-Frazee, & Hurlburt, 2008). The approach has been likened to 'opening the black box' of evidence-based programs, allowing one to 'see inside' multiple programs to gain a sense of their most important features (Evenboer, Huyghen, Tuinstra, Reijneveld, & Knorth, 2016). It is an approach that has the potential to provide practitioners with a set of evidence-informed strategies to use in their daily practice as an alternative to implementing a complete manualised program.

To date, a common elements approach has not been applied to programs for separating families. However, Schramm, Kanter, Brotherson, and Kranzler (2018) used a somewhat similar approach in a systematic review designed to categorise the common content of divorce education programs, with the aim of providing program developers with a framework for selecting content. Their framework identifies three tiers of potential content in divorce education programs (See Table 1).

Schramm and colleagues (2018) offer an important synthesis of divorce education programs, yet it is unclear whether parenting programs for separating parents would cover the same content areas. Such parenting programs arguably have more relevance to the Australian context, given that divorce education programs are much less common in Australia than in the US, as they are not mandated for Australian divorcing couples (unless the couple is planning on going through mediation or if there are concerns about family violence or child abuse and neglect) (Parkinson, 2013). Schramm and colleagues' review also focused solely on the content of divorce education programs and did not cover other parameters such as the delivery format of the program or the therapeutic and educational techniques used by facilitators.

An important feature of the common elements approach is that it aims to identify commonalities across numerous program dimensions. For example, in an analysis of treatment programs for children's behaviour problems, Garland and colleagues (2008) identified common elements across four dimensions. Such a multidimensional approach is likely to offer practitioners a more complete understanding of the common elements in particular areas of practice, enabling them to identify whether and how such elements can be applied in their own practice circumstances. Table 1 outlines the three-tiered framework of content in divorce education programs developed by Schramm and colleagues (2018) and the four dimensions of common elements identified by Garland and colleagues (2008) in their analysis of treatment programs for children's behaviour problems.

| Schramm, Kanter, Brotherson, & Kranzler (2018) | Garland et al. (2008) |

|---|---|

1. Core content: child-centred information, designed to educate parents about promoting children's wellbeing during and after separation (e.g. the impact of divorce on children, reducing interparental conflict, and co-parenting strategies) 2. Strategic content: adult-centred information, designed to promote parents' wellbeing (e.g. self-care strategies, managing divorce issues, and moving forward in life) 3. Supplemental content: speciality content areas (e.g. domestic violence and divorce, children with special needs, long-distance parenting), which may be covered as necessary | 1. Therapeutic content (e.g. information on parent-child relationship building) 2. Treatment techniques (e.g. role playing) 3. Aspects of the working alliance (e.g. consensual goal setting) 4. Other parameters (e.g. treatment duration) |

This rapid review was conducted to answer the following research question: What are the common elements of evidence-based parenting programs that support children's mental health through parental separation? It was conducted to inform the design and delivery of resources for the National Centre for Child Mental Health (Emerging Minds). Emerging Minds assists professionals and organisations who work with children (aged 0-12 years old) and/or parents/families to have the skills to identify, assess and support children at risk of mental health conditions.

We chose to concentrate on parent-focused programs because research suggests that supporting parents is one of the most effective ways to safeguard children's wellbeing through separation (Jeong, Franchett, Ramos de Oliveira, Rehmani, & Yousafzai, 2021; Kaspiew et al., 2015; McIntosh & Tan, 2017), and because many practitioners who work with adults have limited training in, or organisational support for, keeping children's mental health in mind. More specifically, we focused on parenting programs (rather than divorce education programs) because the common elements of such programs are likely to have greater salience in the Australian context, where most separating parents are not mandated to attend divorce education programs.

Methodology

This evidence review involved three stages: (1) a rapid literature search to identify evidence-based parenting programs for separating parents; (2) an analysis of program materials to identify common elements; and (3) consultation with experts to gather feedback on the identified common elements.

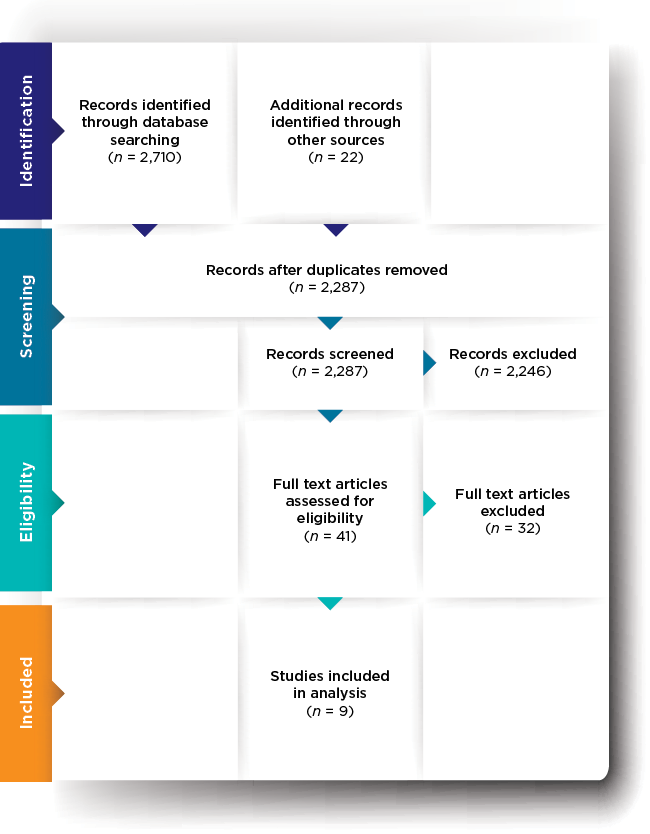

The rapid review was undertaken using the methodology of King and colleagues (2017). Peer-reviewed, English language articles published between 2000 and 2020 were identified through Scopus, MEDLINE and PsycArticles. The date limit was chosen to ensure that the identified program reflected contemporary practice, and the databases were chosen for their relevancy to the topic. Additional peer-reviewed literature was sourced by searching the reference lists of identified articles, relevant reviews and meta-analyses, searching relevant websites and databases of evidence-based programs (e.g. California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare), and hand searching the Journal of Divorce & Remarriage for the years 2000-20. See Appendix A for details of the search strategy and inclusion criteria.

Articles were included if they: (a) were an evaluation demonstrating positive effects of a parenting program for separating or separated parents; (b) in which child (0-12 years old) mental health or wellbeing was a key concern or target outcome; (c) and that were published in a peer-reviewed publication. Programs that focused on the outcomes of both children and teenagers (e.g. a program for parents of 8-15 year olds) were included.

Potential articles were excluded for any of the following reasons: (a) they evaluated a child-focused program; (b) they evaluated a child and parent focused program; (c) they evaluated an adult-focused program in which child mental health or wellbeing was not a key concern or target outcome; (d) they evaluated a divorce education program (as described in the introduction); (e) they were published in a non-peer-reviewed publication; and (f) the quality of evaluative evidence was assessed as 'poor'.

The database search identified a total of 2,710 articles. The hand search of reference lists, reviews and meta-analyses, websites and the Journal of Divorce & Remarriage identified another 22 potentially eligible articles. A total of 2,732 articles was reduced to 2,287 after duplications were removed. Following an analysis of article titles and abstracts, the number of potentially eligible articles was reduced to 41. Application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in the final inclusion of nine articles (which were associated with six programs). For a PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search, see Appendix B.

Data management

The quality of evidence in each identified article was assessed using a framework, adapted from Evans (2003) that provides a hierarchical guide to evaluating the quality of different forms of evidence. To ensure that included programs could be described as 'evidence-based', articles were included if their methodology was assessed as 'excellent', 'good' or 'fair', and excluded if assessed as 'poor' (see Table A1 in Appendix A).

The majority of article exclusions were because programs were child-focused, child and parent focused, adult-focused (where child mental health or wellbeing was not a key concern or target outcome), or divorce education programs. Some well-known programs were excluded from this review for these reasons, including Children of Divorce-Coping with Divorce (Boring et al., 2015), Children of Divorce Intervention Program (e.g. Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, 1985), Child-Parent Relationship Therapy (Dillman Taylor et al., 2011), and Kids in Divorce Situations (Pelleboer-Gunnink, van der Valk, Branje, van Doorn, & Dekovic, 2015).

Common elements analysis

This component of the research used the common elements methodologies of Chorpita and colleagues (2005) and Garland and colleagues (2008). These involve: (1) reviewing all program materials (e.g. program manuals, websites); (2) coding the program elements of each program; (3) determining which program elements were common to at least 50% (three out of six) of the programs.

The materials for each program were independently analysed and thematically coded by both authors. The authors compared their coding for each program, revising and adapting the coding until consensus was reached for each program.

Expert consultation

Seven invited content experts completed an online survey to confirm the validity of the identified common elements (Chorpita et al., 2005; Garland et al., 2008; King et al., 2017). This level of consultation was similar to other published studies. Content experts included program developers, evaluators and key authors of included programs.

For each common element, the content experts were asked whether or not they thought the element should be included in the final list and were prompted to comment on the working definition. The content experts had free-text space to make general comments about the list of common elements, or to make suggestions about additional elements that may have been missed. A common element was only considered for inclusion in the final list if it was endorsed by at least 50% of the content experts.

What does the evidence tell us?

Six evidence-based parenting programs for separating parents were identified in this review (see Appendix C for further details on each program):

- Dads for Life (DFL; Braver, Griffin, & Cookston, 2005)

- Egokitzen (EK; Martínez-Pampliega et al., 2015)

- Family Transitions Triple P (FTTP; Stallman & Sanders, 2014)

- New Beginnings Program (NBP; Sandler et al., 2020; Wolchik et al., 2000; Wolchik et al., 2002; Wolchik et al., 2013)

- New Beginnings Program - Dads (NBP-D; Sandler et al., 2018)

- Parenting Through Change (PTC; DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005).

All six programs were in-person, group-based programs. Two of the programs were delivered to mothers only (PTC, NBP), while two programs focused on fathers (DFL, NBP-D), with DFL focusing specifically on fathers who did not have primary parental responsibility of their children. The other two programs were for both mothers and fathers (EK, FTTP), with the latter focusing on parents who had divorced in the previous two years. The programs ran for between eight and 11 sessions, with some programs also involving concurrent individual elements such as telephone check-ins. Most programs involved weekly sessions, with the average session duration being 1-2 hours. Program facilitators had various professional backgrounds (e.g. psychologists, counsellors, clinicians). Some programs required facilitators to have a minimum-level skillset (e.g. a Masters qualification), and most required facilitators to attend pre-program training in delivering the program. Ongoing supervision for program facilitators was also provided and required in a number of programs.

Four of the included programs were developed and evaluated in the United States (DFL, NBP, NBP-D, PTC), while one was developed and evaluated in Spain (EK) and another in Australia (FTTP). Four programs were evaluated using randomised controlled trials (DFL, NBP, NBP-D, FTTP), with the remaining programs using mixed methods (PTC) and quasi-experimental (EK) methodologies. NBP was the only program with evaluative evidence rated as 'excellent', as it had been subject to multiple RCTs.

Table 2 provides the names and definitions of the common elements found across the six programs, as well as which programs featured each common element. The common elements are sorted according to:

- program content: the specific topics that were covered in the programs

- program techniques: the particular techniques and strategies that were used to engage parents and convey the program content.

Fifteen common elements were identified across the six programs. Four of the common elements related to program content (i.e. emotional management in separation, parenting in separation, co-parenting in separation, and the impact of separation on children), while 11 involved program techniques (i.e. psychoeducation, group participation, skills practice, personalising content, problem solving, assigning and reviewing homework, normalising difficulties, encouraging, video content, attending to group process, and providing materials).

Many of the common elements received endorsement from all of the content experts, and all were endorsed by at least 50% (or four out of seven) of the experts. The content experts' comments led to improvements in the reporting of results, including revised titles and definitions for numerous common elements.

| Program content | ||

|---|---|---|

| Element | Definition | Programs with element |

| Emotional management in separation | Information on managing or modulating emotions throughout separation, including anger management, resilience, coping skills, relaxation, and cognitive-behavioural techniques | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Parenting in separation | Information on providing effective parenting throughout separation, including communicating with children about separation, responding to children's adjustment concerns, and appropriate visitation behaviours | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Co-parenting in separation | Information on improving the quality of the co-parental relationship throughout separation, including communication skills between co-parents, reducing interparental conflict, and developing co-parenting plans | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D |

| The impact of separation on children | Information on the impact of separation on children's wellbeing, including the negative impacts of interparental conflict, the warning signs of adjustment concerns, and strategies for encouraging positive child adjustment throughout separation | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D |

| Program techniques | ||

|---|---|---|

| Element | Definition | Programs with technique |

| Psychoeducation | Teaching through didactic instruction, or through providing written materials or media-based aides, on topics such as emotional management, parenting, co-parenting and the impact of separation on children | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Group participation | Parents' active participation in group sessions, including their contribution to positive group dynamics, provision of positive feedback to other participants and sharing of relevant personal experiences | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Skills practice | Practising parenting and relationship skills using techniques such as behavioural rehearsal and role play. Skills may include appropriate discipline, talking to children about divorce and conflict resolution. | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Personalising content | Tailoring the content of group programs to individual participants for greater relevance and increased chance of uptake. This may be achieved through personalised feedback, phone calls to participants, individual sessions concurrent with group process and personalised goal setting. | DFL, EK, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Problem solving | Coaching and educating parents to generate alternative solutions, evaluate different options and consider consequences | DFL, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Assigning and reviewing homework | Assigning and/or reviewing activities to complete between sessions, most commonly skills practice with family members | DFL, EK, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Encouraging | Encouraging parents to stay motivated and engaged in the program by recognising and positively reinforcing their efforts and progress and encouraging them to remain hopeful | DFL, FTTP, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Normalising difficulties | Using direct interventions or group processes to reassure parents that their difficulties with separation, parenting and other life circumstances are shared by others going through separation | DFL, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Video content | Delivering educational material using video and related media. Examples of video use may include vignettes, peer testimonials and skill modelling. Video may also be used as a technique for feedback on skills practice, such as when parents record themselves practising a play technique with their child. | DFL, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Attending to group process | Attending to group processes and dynamics using strategies such as role modelling group behaviour, establishing group norms, encouraging involvement and building trust | EK, NBP, NBP-D, PTC |

| Providing materials | Providing written material that serves an educative purpose, including relevant literature and media aides, worksheets and behaviour change plans | FTTP, NBP, NBP-D |

Evidence-informed implications for practice

Most Australian families undergoing separation do not receive support from family dispute resolution services (Kaspiew et al., 2015). Some manage separation and co-parenting without any assistance from health and welfare professionals. Others receive support from practitioners who work outside of family relationship services, such as teachers, social workers, psychologists and general practitioners (Mahony et al., 2015). The extent to which the interventions made by these practitioners are evidence-informed is unknown as individual practice is rarely evaluated.

The common elements approach used in this review provides an opportunity to make individual practice more informed by evidence. By breaking up large, evaluated programs into smaller components, the common elements identified in this review could be used by individual practitioners working with separating families to make their practice more rigorous. Psychologists and counsellors, for instance, could be provided with examples of parenting skills practices and homework tasks to use with clients undergoing separation. Similarly, practitioners could be provided with information on each of the four major content areas covered in parenting programs for separating parents, which could be used to inform the advice or interventions they offer to parents, or which could be directly shared with parents in the form of information sheets or online resources.

Managers and other leaders in organisations could develop processes that encourage the uptake of common elements among their staff, such as 'packaging' information on common elements into toolkits for practitioners. Ultimately, common elements can be embedded into system-wide practice frameworks with 'strong implementation support, involving managers and practitioners assessing, planning, embedding and maintaining processes and practices that support their uptake' (Centre for Evidence and Implementation, n.d.). Such system-wide integration of common elements could be expected to improve efforts to safeguard children's mental health across the health and welfare service system.

The evidence gathered in this review could be further conveyed through practice resources that provide detailed guidance for specific practitioners about 'when, where, who with, and how to use them' (Mitchell, 2017, p. 21). For an example of a resource discussing how to apply the common elements identified in this rapid review in practice, see Paterson, Price-Robertson, and Hervatin (2021).

Supporting parents through separation is key to ensuring more favourable outcomes for their children and the family. With so many parents receiving support outside of parenting programs and from practitioners who work outside of family dispute resolution altogether, it is important that practice in a range of health and welfare roles is guided by evidence on 'what works'. The common elements approach is a useful approach to using evidence from evaluated programs for separating parents in other practice settings.

While the programs reviewed in this paper were often designed for and accessed by parents currently going through parental separation, some of them could be accessed at any stage post-separation (even years later). Parenting demands and parental relationships continue to evolve post-separation and the common elements of parenting programs to support parents and, through them, the mental health of their children continue to be relevant.

Limitations when using these findings

The common elements approach provides a frequency count of the practice elements that show up across multiple programs. While such frequency counts offer important information about the practices that are commonly used in particular contexts, they cannot indicate whether particular elements are necessary or sufficient for clinical change. In order to establish the causal effects of various practice elements, experimental methodology would be required (Chorpita et al., 2005).

There are multiple possible levels for analysing the activities that take place in parenting programs, and different researchers may have identified different common elements even when analysing the same set of programs. Following Garland and colleagues (2008), we selected the therapeutic strategy level of analysis, which represents a middle ground between macro-level analyses, where programs are characterised by broad theoretical orientation, and micro-level analyses, which focuses on discrete verbal and nonverbal behaviours.

Our decision to focus on programs that had been evaluated and published in peer-reviewed literature ensured the literature search was appropriately scoped; however, some popular (but less rigorously evaluated) programs may have been excluded. If the search included non-peer-reviewed literature, it is possible that different or additional common elements would have been identified.

Other limitations relate to the relevance and scope of the evaluated programs. It could be argued that the programs identified in the current research are largely Anglocentric, conveying Westernised understandings of parenting and family life. It is therefore unclear to what extent they would be acceptable to, and appropriate for, culturally, racially and linguistically diverse parents. The programs also convey limited information about other forms of diversity in family structure and circumstance, including non-heterosexual family structures. As more evidence-based programs for separating parents are developed - including those focusing on the needs of culturally, racially and linguistically diverse families - it is likely the common elements associated with such programs will increase and/or change. It is also worth noting that common elements already allow for flexible adaption of evidence-based practice to varied and shifting practice circumstances. For example, the list of common elements above could be used alongside various other culturally sensitive practices by practitioners working with separating families in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

It could also be argued that content on topics such as domestic violence and child protection should have a place in most parenting programs for separating parents. All of the programs identified in this review explicitly focus on reducing parental conflict, which helps insulate children from the potential negative consequences of parental separation. However, the programs did not consistently offer detailed information on topics such as domestic violence, coercive control and child abuse and neglect, which are all common throughout Australian society (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2021). In their synthesis of divorce education programs, Schramm and colleagues (2018) suggested that information on topics such as domestic violence should be considered 'supplemental content', to be provided as necessary. Australian parenting programs for separating parents may benefit from including such 'supplemental content' as part of their program, and by providing separate targeted specialist interventions (or referrals to such interventions) as necessary.

Conclusion

This rapid review identified 15 common elements of evidence-based parenting programs that support children's mental health through parental separation. It provides an understanding of the contents and processes used in evidence-based parenting programs for separating parents as an initial step in assisting practitioners in diverse health and welfare sectors to develop their skills in working with parents experiencing separation. It allows practitioners working with separating families to use and customise elements that have been found to work across several evaluated programs to ensure their practice is informed by evidence. Additional resources for practitioners need to be developed to facilitate the use of the evidence from this review in practice.

References

- Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650-666. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

- Amato, P. R., Kane, J. B., & James, S. (2011). Reconsidering the 'good divorce'. Family Relations, 60(5), 511-524. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00666.x

- Attorney-General's Department. (n.d.). Family relationship services. Canberra: Attorney-General's Department. Retrieved from www.ag.gov.au/families-and-marriage/families/family-relationship-services

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Parental divorce or death during childhood (Cat. no. 4102.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2021). Family, domestic and sexual violence. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence

- Axford, N., & Morpeth, L. (2013). Evidence-based programs in children's services: A critical appraisal. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 268-277.

- Boring, J. L., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J. Y., Horan, J. J., & Velez, C. E. (2015). Children of divorce-coping with divorce: A randomized control trial of an online prevention program for youth experiencing parental divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 999-1005. doi:10.1037/a0039567

- Bowers, J. R., Ogolsky, B. G., Hughes Jr, R., & Kanter, J. B. (2014). Coparenting through divorce or separation: A review of an online program. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 55(6), 464-484. doi:10.1080/10502556.2014.931760

- Braver, S. L., Griffin, W. A., & Cookston, J. T. (2005). Prevention programs for divorced nonresident fathers. Family Court Review, 43(1), 81-96. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2005.00009.x

- Centre for Evidence and Implementation. (n.d.) Using a 'common elements approach' in Victorian human services. Melbourne: Centre for Evidence and Implementation. Retrieved from www.ceiglobal.org/our-work-original/building-capacity-through-implementation-science/using-common-elements-approach-victorian-human-services

- Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence-based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 5-20. doi:10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6

- D'Onofrio, B., & Emery, R. (2019). Parental divorce or separation and children's mental health. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 100-101. doi:10.1002/wps.20590

- DeGarmo, D. S., & Forgatch, M. S. (2005). Early development of delinquency within divorced families: Evaluating a randomized preventive intervention trial. Developmental Science, 8(3), 229-239. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00412.x

- Dillman Taylor, D., Purswell, K., Lindo, N., Jayne, K., & Fernando, D. (2011). The impact of child parent relationship therapy on child behavior and parent-child relationships: An examination of parental divorce. International Journal of Play Therapy, 20(3), 124-137.

- Evans, D. (2003). Hierarchy of evidence: A framework for ranking evidence evaluating healthcare interventions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12, 77-84. doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00662.x

- Evenboer, K. E., Huyghen, A. M. N., Tuinstra, J., Reijneveld, S. A., & Knorth, E. J. (2016). Opening the black box: Toward classifying care and treatment for children and adolescents with behavioral and emotional problems within and across care organizations. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(3), 308-315. doi:10.1177/1049731514552049

- Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children's disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 505-514. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2

- Jeong, J., Franchett, E. E., Ramos de Oliveira, C. V., Rehmani, K., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2021) Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 18(5): e1003602. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602

- Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., Qu, L., & the Family Law Evaluation Team. (2009). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reform. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Kaspiew, R., Carson, R., Dunstan, J., De Maio, J., Moore, S., Moloney, L. et al. (2015). Experiences of Separated Parents Study (Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- King, V., Garritty, C., Stevens, A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Hartling, L., Harrod, C. et al. (2017). Performing rapid reviews. In A. Tricco, E. Langlois, & S. Straus (Eds.), Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: A practical guide (pp. 21-38). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Levkovich, I., & Eyal, G. (2020). 'I'm caught in the middle': Preschool teachers' perspectives on their work with divorced parents. International Journal of Early Years Education, 1-15. doi:10.1080/09669760.2020.1779041

- McIntosh, J. E. & Tan, E. S. (2017). Young children in divorce and separation: Pilot study of a mediation based parent education program. Family Court Review, 55(3). doi: 10.1111/fcre.12291

- Mahony, L., Walsh, K., Lunn, J., & Petriwskyj, A. (2015). Teachers facilitating support for young children experiencing parental separation and divorce. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 24(10), 2841-2852.

- Martínez-Pampliega, A., Aguado, V., Corral, S., Cormenzana, S., Merino, L., & Iriarte, L. (2015). Protecting children after a divorce: Efficacy of Egokitzen. An intervention program for parents on children's adjustment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3782-3792. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0186-7

- Mitchell, P. (2017). Common practice elements for child and family services: A discussion paper. Richmond, Vic.: Berry Street Victoria, Inc.

- Parkinson, P. (2013). The idea of Family Relationship Centres in Australia. Family Court Review, 51(2), 195-213.

- Paterson, N., Price-Robertson, R., & Hervatin, M. (2021). Working with separating parents to support children's wellbeing: What can we learn from evidence-based programs? Adelaide: Emerging Minds. Retrieved from emergingminds.com.au/resources/working-with-separating-parents-to-support-childrens-wellbeing-what-can-we-learn-from-evidence-based-programs

- Pedro-Carroll, J. L. (2005). Fostering children's resilience in the aftermath of divorce: The role of evidence-based programs for children. Family Court Review, 43, 52-64. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2005.00007.x

- Pedro-Carroll, J. L., & Cowen, E. L. (1985). The Children of Divorce Intervention Program: An investigation of the efficacy of a school-based prevention program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(5), 603-611. doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.5.603

- Pelleboer-Gunnink, H. A., van der Valk, I. E., Branje, S. J. T., van Doorn, M. D., & Dekovic, M. (2015). Effectiveness and moderators of the preventive intervention kids in divorce situations: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(5), 799-805.

- Poli, C. F., Molgora, S., Marzotto, C., Facchin, F., & Cyr, F. (2017). Group interventions for children having separated parents: A systematic narrative review. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 58(8), 559-583. doi:10.1080/10502556.2017.1345243

- Relationships Australia. (2020). Family Relationship Centres. Retrieved from relationships.org.au/services/family-relationship-centres

- Rose, S. R. (2009). A review of effectiveness of group work with children of divorce. Social Work with Groups, 32(3), 222-229. doi:10.1080/01609510902774315

- Sandler, I., Gunn, H., Mazza, G., Tein, J. Y., Wolchik, S., Berkel, C. et al. (2018). Effects of a program to promote high quality parenting by divorced and separated fathers. Prevention Science, 19(4), 538-548. doi:10.1007/s11121-017-0841-x

- Sandler, I., Wolchik, S., Mazza, G., Gunn, H., Tein, J. Y., Berkel, C. et al. (2020). Randomized effectiveness trial of the new beginnings program for divorced families with children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 49(1), 60-78. doi:10.1080/15374416.2018.1540008

- Schramm, D. G., & Becher, E. H. (2020). Common practices for divorce education. Family Relations, 69, 543-558.

- Schramm, D. G., Kanter, J. B., Brotherson, S. E., & Kranzler, B. (2018). An empirically based framework for content selection and management in divorce education programs. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 59(3), 195-221. doi:10.1080/10502556.2017.1402656

- Schramm, D. G., & McCaulley, G. (2012). Divorce education for parents: A comparison of online and in-person delivery methods. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 53(8), 602-617. doi:10.1080/10502556.2012.721301

- Stallman, H. M., & Sanders, M. R. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of Family Transitions Triple P: A group-administered parenting program to minimize the adverse effects of parental divorce on children. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 55(1), 33-48. doi:10.1080/10502556.2013.862091

- Wolchik, S. A., Sandler, I. N., Millsap, R. E., Plummer, B. A., Greene, S. M., Anderson, E. R. et al. (2002). Six-year follow-up of preventive interventions for children of divorce: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(15), 1874-1881. doi:10.1001/jama.288.15.1874

- Wolchik, S. A., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J.-Y., Mahrer, N. E., Millsap, R. E., Winslow, E. et al. (2013). Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families: Effects on mental health and substance use outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 81(4), 660-673.

- Wolchik, S. A., West, S. G., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J.-Y., Coatsworth, D., Lengua, L. et al. (2000). An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 843-856.

Appendix A: Search strategy and inclusion criteria

Databases were searched using 'keywords', 'abstract', and 'title' domains (when domain-limiting was available on the database). The following search strategy was used: ((child* OR parent* OR family) AND ('mental health' OR 'mental illness') AND (divorce* OR separat* OR seperat*) AND (program OR intervention)). In order to identify relevant reviews and meta-analyses of evidence-based programs, a second search was conducted using the above search strategy with 'AND (review OR 'meta-analysis')' added.

The quality of evidence in each article was assessed using the hierarchical guide to evaluating the quality of different forms of evidence adapted from Evans (2003) (see Table A1).

| Quality of evidence identified in studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor |

Systematic reviews Meta-analyses Multi-centre studies Multiple RCTs | RCT Observational studies | Uncontrolled trials with dramatic results Pre-post studies Non-randomised controlled trials | Descriptive studies Case studies Expert opinion Studies with poor methodological quality |

| Parameters | Inclusion |

|---|---|

| Location | Australia or countries with comparable social care systems |

| Language | English |

| Publication date | January 2000 - June 2020 |

| Publication focus | Common elements of parenting programs to support child mental health through separation |

| Intervention type | Evidence-based programs |

| Publication type | Peer-reviewed |

| Study type | Evaluation research and evidence reviews |

| Examples of keyword searches | Child/ren's; parent/s; family/ies; mental health; mental illness; divorce; separation; program; intervention |

Appendix B: PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search

Appendix C: Characteristics of included programs

The table can also be viewed on page 16 of the PDF.

| Name | Focus | Location | Target group | Providers | Delivery mode | Evaluation | Evidence rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dads for Life | Child mental health and adjustment | United States | Recently divorced, non-custodial fathers with child/ren aged 4-12 years | 2 x Masters-level counsellors (1 male, 1 female) | 8 x 1.75-hour weekly group sessions and 2 x 0.75-hour individual sessions | RCT (Braver et al., 2005) | Good |

| Egokitzen | Post-divorce intervention for parents | Spain | Parents with children and/or adolescents | Psychologists specialised in clinical psychology and family intervention | 11 x 1.5-hour sessions | Quasi-experimental (waitlist comparison group) (Martinez-Pampliega et al., 2015) | Fair |

| Family Transitions Triple P | Impact of divorce on a child's adjustment and development | Australia | Parents who had divorced in the previous 2 years with children aged 2-14 years | Counsellors | 12 x 2-hour group sessions and 3 x individual telephone consultations | RCT (Stallman & Sanders, 2014) | Good |

| New Beginnings Program | Parent-child relationship, child exposure to interparental conflict, and quality of parenting | United States | Mothers of children aged 3-18 years | 2 x Masters-level clinicians | 10 x 2-hour group sessions and 2 x individual sessions | RCT RCT RCT RCT | Excellent |

| New Beginnings Program - Dads | Quality of father parenting post-divorce | United States | Fathers of children aged 3-18 years | Not specified | 10 x 2-hour group sessions and 2 x individual sessions | RCT (Sandler et al., 2018) | Good |

This resource has been co-produced by CFCA and Emerging Minds as part of the National Workforce Centre for Child Mental Health. The Centre is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health under the National Support for Child and Youth Mental Health Program.

At the time of writing, Rhys Price-Robertson was a Workforce Development Manager and Nicole Paterson was a Research Officer at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

For advice and feedback, many thanks to Rachel Carson, Marion Forgatch, Kelly Gribben, Nicole Mahrer, Ana Martinez-Pampliega, Michele Porter, David Schramm, and Sharlene Wolchik.

Featured image: © GettyImages/[email protected]

978-1-76016-237-5