What works to improve young children’s social, emotional and behavioural wellbeing?

October 2021

Download Policy and practice paper

Summary

The development of social, emotional and behavioural skills during early childhood is crucial to children's overall development and later life. However, some children experience difficulties that may compromise their development and future opportunities. This rapid evidence review identifies national and international prevention and early intervention programs that are effective at improving the social, emotional and behavioural health of at-risk children under the age of five.

Key messages

-

Parenting programs appear to hold promise in supporting children at risk of experiencing social, emotional or behavioural difficulties. These programs may support families experiencing various risk factors and may be able to be delivered in different formats to suit practitioner and family needs.

-

Programs that support mothers experiencing poor mental health may provide benefits for some child social, emotional or behavioural outcomes.

-

Programs delivered by trained professionals show the greatest chance of effecting change.

-

Identifying the risk factors children experience may help practitioners choose the type of program most suited to the child's situation.

-

Programs appear to be effective through a range of delivery formats including individual or group, in-home or community-based.

Introduction

Early childhood, birth through to around five years of age, is characterised by rapid and significant development, including in children's social, emotional and behavioural skills (Moore, Arefadib, Deery, & West, 2017; Tully, 2020). Ensuring children's social, emotional and behavioural (SEB) wellbeing is nurtured during the early childhood period is crucial to later outcomes. For instance, more favourable SEB wellbeing during early childhood is associated with higher levels of academic achievement and better mental health (Meagher, Arnold, Doctoroff, Dobbs, & Fisher, 2009; Sanson et al., 2009; Toumbourou, 2012; Toumbourou, Williams, Letcher, Sanson, & Smart, 2011). Young children who have higher levels of SEB wellbeing are also less likely to experience depression, hostile behaviour or aggressive interpersonal behaviour later in life (Jones, Brown, & Lawrence, 2011; Meagher et al., 2009; Toumbourou et al., 2011).

During the early childhood period, some children may experience SEB difficulties that place them at risk of developing problems later, such as those identified above (Bagner, Rodríguez, Blake, Linares, & Carter, 2012; Bor, McGee, & Fagan, 2004; Hemmi, Wolke, & Schneider, 2011; Lonigan & Phillips, 2001; Toumbourou et al., 2011; Tully, 2020). Children who exhibit SEB difficulties respond to contexts and stimuli differently from typically developing children from similar cultural or ethnic backgrounds (Poulou, 2015; Tully, 2020). Specifically, children with SEB difficulties may be inhibited in their social relationships, self-care or educational opportunities (Poulou, 2015). In Australia, the prevalence of SEB difficulties in toddlers and preschoolers (aged 1.5 to six years) is estimated to be between 13% and 23% (Oh, Mathers, Hiscock, Wake, & Bayer, 2015). National levels of SEB difficulties are consistent with international estimates of around 20% in children aged one to seven years (Vasileva, Graf, Reinelt, Petermann, & Petermann, 2020).

Early childhood is therefore recognised as a key developmental period, and prevention and early intervention may be necessary to target risk factors and stem the potential development of later problems, including diagnosable mental health conditions (McLuckie et al., 2019; Oh et al., 2015). Risk factors for SEB difficulties usually do not occur in isolation, and many children are exposed to multiple risk factors at a time, intensifying their level of risk. Risk factors for SEB difficulties during early childhood are found in a range of domains (McLuckie et al., 2019) including:

- child (e.g. prematurity; temperament)

- family (e.g. parental mental health; parental substance use; caregiver-child attachment; domestic and family violence; child maltreatment)

- structural (e.g. socio-economic status; ethnicity).

Evidence-based programs targeting SEB difficulties

Given that early childhood is a time of critical development, as well as potential exposure to risk factors, it is vital that professionals and service providers who work with children use effective programs to support them. Those programs should target known risk factors and best support favourable outcomes, minimise unintended consequences and reduce financial costs (Marsenich, n.d.; University of Canberra Library, 2020; US Department of Health and Human Services & Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). However, navigating the number of options that exist may be challenging for practitioners and service providers (McLuckie et al., 2019). Additionally, information about many of these programs is only available in the scientific literature, which may be inaccessible to many practitioners. Therefore, identifying programs targeting early childhood may help guide practitioners in their decision making and service provision (Boustani et al., 2020; McLuckie et al., 2019).

A 2019 evidence review examined prevention and early intervention programs for children aged birth through to five years at risk of mental health difficulties (McLuckie et al., 2019). The review included children at risk of, or diagnosed with, SEB difficulties or mental health disorders and examined outcome measures. However, it did not investigate program outcomes and only included studies published in 2012 or earlier. Consequently, there is no current synthesis of evidence-based, effective programs targeting SEB difficulties during early childhood.

The aim of this rapid review was to identify and describe effective prevention and early intervention programs that seek to improve SEB wellbeing during early childhood for children experiencing, or at risk of, SEB difficulties. The findings of this review will help practitioners identify the types of programs that might be useful to support children at risk of SEB difficulties. In particular, the findings provide practitioners with insight into which programs are most suitable for children experiencing different types of risk factors.

Methodology

The topic for this review was identified and scoped in consultation with Emerging Minds: the National Workforce Centre for Child Mental Health as the foundation for developing practitioner resources. This rapid evidence review was guided by methodology outlined by King and colleagues (2017). Rapid reviews are a useful approach to identifying and synthesising relevant evidence on a particular issue in a timely fashion. The process included two main stages:

- a literature search to identify effective evidence-based programs targeting early childhood SEB difficulties

- a review of reported program features to identify types of programs and characteristics showing the greatest likelihood of effectiveness.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Appendix A. Included studies were drawn from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Given the aim was to identify and describe effective prevention and early intervention programs, only reviews showing effectiveness on one or more of the targeted outcomes were included. Further, reviews where all or most studies were conducted in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries were included to maximise the generalisability of the findings to the Australian context.

Features of programs that are assessed in this review include:

- which types of programs are effective for which outcomes

- where available in the included literature, which characteristics (e.g. delivery mode, setting, types of providers) show efficacy.

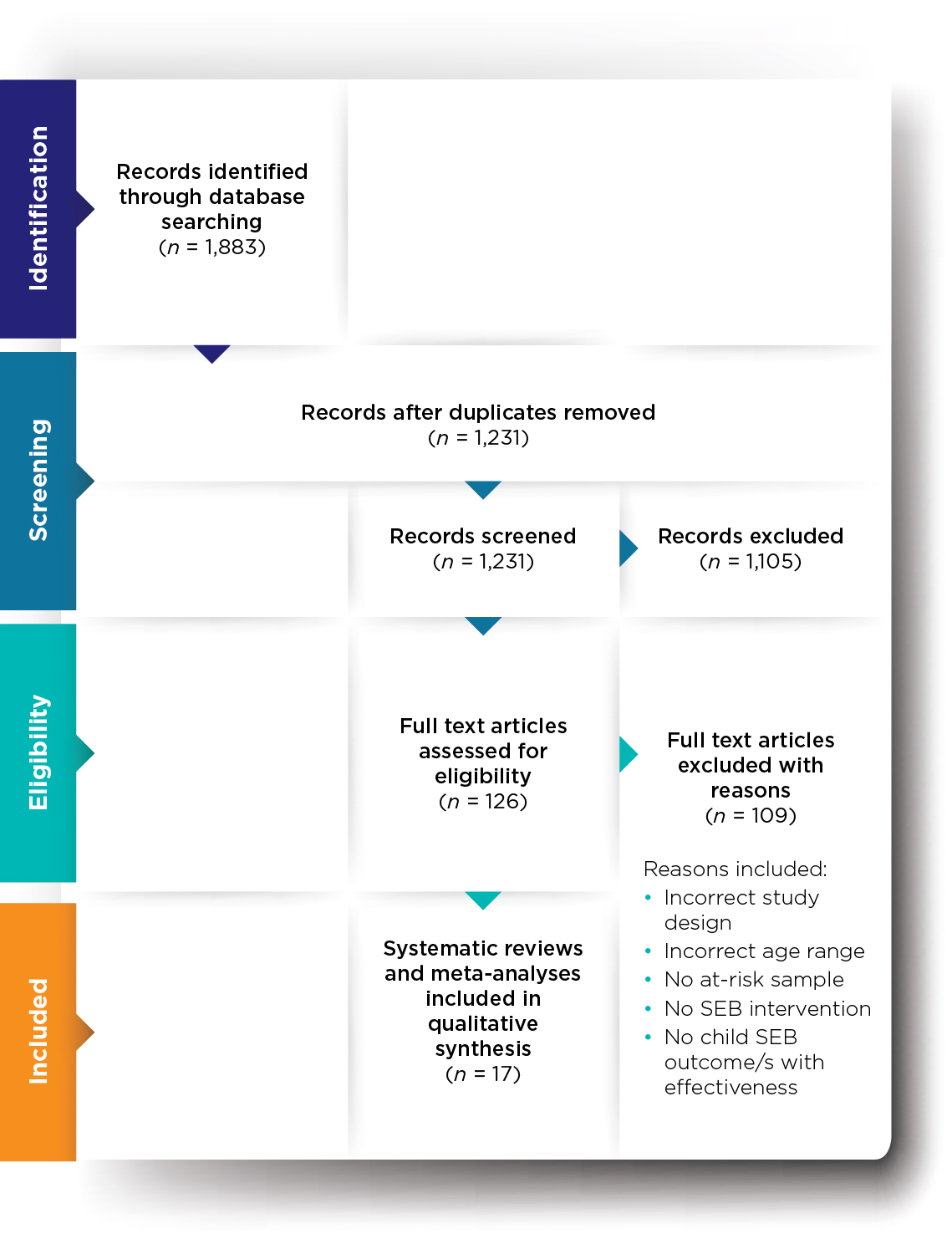

Forty-four databases were searched for peer-reviewed literature. Databases were accessed through the Australian Institute of Family Studies library and included Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ERIC, Gale, Informit, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect and SocINDEX. The search targeted English language systematic reviews and meta-analyses that met the inclusion criteria and were published between May 2010 and April 2020. Searching identified 1,883 articles, which were reduced to 1,231 after duplicates were removed. Initial screening resulted in 126 full-text articles being assessed for eligibility, with 17 meeting criteria for inclusion (Appendix A). Full details are recorded in the PRISMA flow diagram (see Appendix B).

Reviews were only included if they showed effectiveness against one or more variables of interest (see Appendix A). However, some reviews reported weak, inconsistent or marginal findings of effectiveness. Those reviews are included in Appendix C. However, this paper focuses on the reviews that reported the most robust findings as these are likely to be more meaningful for practitioners.

Included reviews reported on prevention or early intervention for children at risk of or experiencing SEB difficulties. Reviews are summarised across the following target groups:

- children with early or existing SEB difficulties (n = 1)

- pre-term children/low birth weight children (n = 7)

- children of parents with mental health conditions, mainly depression (n = 3)

- children and families in other vulnerable circumstances (n = 6).

What does the evidence tell us?

Children with SEB difficulties

Only one review focused on children with previously identified SEB difficulties. This review found that group-based parenting programs were effective in reducing emotional, behavioural and externalising problems, and improving parent-child interaction (Barlow, Bergman, Kornør, Wei, & Bennett, 2016). However, programs did not appear to be effective at improving internalising problems or social skills. Programs were delivered by trained professionals in group-based settings. Program duration ranged from one week to seven months with sessions lasting between one and 2.5 hours.

Pre-term/low birth weight children

Of the seven reviews that targeted low birth weight/pre-term children:

- two focused on studies that used Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC: method of care for pre-term infants where the infant is carried, usually by the mother, with skin-to-skin contact) (Akbari et al., 2018; Athanasopoulou & Fox, 2014)

- one included studies using music therapy (using music and a therapeutic relationship to promote infant development and secure infant-caregiver attachment) (Bieleninik, Ghetti, & Gold, 2016)

- two focused on maternal voice interventions (talking, singing, reading; may be live or pre-recorded) (Filippa et al., 2017; Provenzi, Broso, & Montirosso, 2018)

- two included parenting programs (focusing on teaching skills and/or parent-child relationship/attachment) (Herd, Whittingham, Sanders, Colditz, & Boyd, 2014; Zhang, Kurtz, Lee, & Liu, 2014).

Across reviews, the most robust and promising findings appear to rest with KMC (Akbari et al., 2018) in effecting improvement in child self-regulation and parent-child interaction (Athanasopoulou & Fox, 2014), and parenting programs in effecting improvement in infant developmental outcomes, child behaviour, mother-child interaction, maternal sensitivity and maternal responsiveness (Herd et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). KMC failed to impact child social-emotional functioning and temperament. Information about provider, setting and dose were not reported for KMC.

Parenting programs were delivered by trained professionals in home- and group-based settings; programs durations ranged from one week to three years but session lengths were not reported.

Children of parents with a mental illness

Three reviews targeted children of parents with a mental illness. All included studies within those reviews that targeted mothers with a mental illness. Two reviews investigated parental mental health programs (Goodman, Cullum, Dimidjian, River, & Kim, 2018; Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic, & Linder, 2017) and one focused on parent-infant dyadic programs (Thanhäuser, Lemmer, de Girolamo, & Christiansen, 2017). All reviews included studies that delivered interventions using cognitive behavioural therapy and counselling, among other approaches (Goodman et al., 2018; Letourneau et al., 2017; Thanhäuser et al., 2017). Two reviews found consistent evidence that parental mental health programs were effective in improving:

- overall child functioning (as well as specific domains of neuro-behavioural functioning and dysregulation)

- overall mother-infant interaction

- maternal/infant behaviour during mother-infant interactions (Goodman et al., 2018; Thanhäuser et al., 2017).

One review also reported favourable outcomes on children's socio-emotional competence (Goodman et al., 2018).

Only one review reported delivery details (Thanhäuser et al., 2017). Those programs were delivered by trained professionals to mothers, families and in groups; session durations ranged from 15 minutes to five hours. One review of parental mental health programs included seven interventions that used components of parenting programs (Letourneau et al., 2017). That review did not provide overall findings. However, the review noted that some studies (50%) showed some promise for maternal-child interaction approaches supporting favourable maternal-child relationship outcomes, despite multiple limitations. Overall, reviews showed no improvements in emotional or behavioural problems (Goodman et al., 2018), or various behavioural and developmental indicators (Letourneau et al., 2017).

Children and families in other vulnerable circumstances

This group of reviews included children and families experiencing low socio-economic status, financial stress, child maltreatment, past/current involvement with the welfare system, low education, or parental disadvantage associated with their immigration status. These reviews included studies on parent-infant dyadic programs (Barlow, Bennett, Midgley, Larkin, & Wei, 2015), parenting programs (n = 4) (Grube & Liming, 2018; Letourneau et al., 2015; O'Hara et al., 2019; Rayce, Rasmussen, Klest, Patras, & Pontoppidan, 2017), and preschool social-emotional learning (SEL) programs (Murano, Sawyer, & Lipnevich, 2020).

Overall, findings varied across reviews, including across those examining parenting programs. Regarding parenting programs for children and families in vulnerable circumstances, favourable outcomes were found for:

- parent-child attachment (Grube & Liming, 2018; Letourneau et al., 2015; O'Hara et al., 2019)

- mother-infant interaction (Letourneau et al., 2015)

- parental sensitivity (O'Hara et al., 2019; Rayce et al., 2017)

- indicators of child stress (i.e. salivary cortisol) (Grube & Liming, 2018)

- internalising and externalising behaviours (Grube & Liming, 2018)

- child behaviour (Rayce et al., 2017)

- parent-child relationship (Rayce et al., 2017).

Despite favourable findings for the outcomes listed above, conflicting findings were reported for two outcomes. Other reviews reported no improvements for child behaviour (Letourneau et al., 2015; O'Hara et al., 2019) and parent-child attachment (Rayce et al., 2017). No improvements were also reported for child development (Grube & Liming, 2018; Rayce et al., 2017), emotional regulation (Grube & Liming, 2018), child mental health and socio-emotional development (O'Hara et al., 2019), cognitive behaviour, internalising behaviours and externalising behaviours (Rayce et al., 2017). Parenting programs were delivered by trained professionals and coaches, across a range of delivery modes (in person, web-based, individual, and group), in the home and in other environments, from 10 weeks in duration through to 24 months with sessions ranging from 45 minutes to three hours.

Preschool SEL programs were effective at improving social skills, emotional skills and behavioural problems (Murano et al., 2020). Those programs were delivered in person in a variety of settings (home, school, community) by trained providers. Details of frequency and duration were not reported.

Parenting programs

Parenting programs, reported in seven of the 17 included reviews, showed the most promising results across target groups and outcomes. Additionally, programs delivered by trained professionals appeared to be consistently effective. Parenting programs can be delivered in a variety of settings using different strategies and approaches; hence, these are likely to appeal to practitioners and provide a practical option for service delivery. As such, this discussion will focus on parenting programs.

Parenting programs showed effectiveness in improving a range of child and parent outcomes, including:

- parent-child interaction/relationship (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016; Rayce et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2014)

- emotional problems (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016)

- behavioural problems/overall behaviour (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016; Rayce et al., 2017)

- externalising problems (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016; Grube & Liming, 2018; Herd et al., 2014)

- parent-child interaction/attachment (Grube & Liming, 2018; Rayce et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2014)

- maternal sensitivity/responsiveness (O'Hara et al., 2019; Rayce et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2014)

- infant development (Zhang et al., 2014)

- internalising problems (Grube & Liming, 2018; Herd et al., 2014)

- indicators of child stress (Grube & Liming, 2018).

Conversely, four of the reviews found no effect for a number of child and parent outcomes, including social skills/socio-emotional development (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016; O'Hara et al., 2019), internalising problems (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016; Rayce et al., 2017), externalising problems (Rayce et al., 2017), cognitive behaviour (Rayce et al., 2017), attachment (O'Hara et al., 2019; Rayce et al., 2017), child development/developmental functioning (Grube & Liming, 2018; Rayce et al., 2017), child mental health (O'Hara et al., 2019), child behaviour (O'Hara et al., 2019) and emotional regulation (Grube & Liming, 2018).

There is substantial evidence of the effectiveness of parenting programs in providing favourable outcomes for multiple aspects of children's development (Johnson & Katz, 1973; Rose, 1974). Typically, parenting programs are focused programs that aim to help parents improve their relationship with their child and enhance emotional and behavioural outcomes (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016). These programs are generally guided by a specific theoretical approach, which likely supports their effectiveness. They include multiple techniques, strategies and activities. For instance, included reviews reported on programs that used videotaped vignettes or modelling, problem solving, discussion groups, psychological support, information provision, observing infant cues, and teaching games and activities (Barlow, Bergman et al., 2016; Herd et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Thus, parenting strategies are likely to be a valuable addition to practitioners' toolkits.

Similarly, parenting programs were delivered in a range of settings (group, individual, home, community). Such programs may therefore be a viable option for a range of practitioners across settings and interaction models (e.g. one-to-one, groups). As such, it is likely that practitioners would be able to find at least one appropriate strategy or activity to use, allowing broad applicability across settings.

However, the use or delivery of parenting programs typically relies on a manualised or standardised program or curriculum. There may be less opportunity for practitioners to provide this level of support. Further investigation of parenting programs is needed to identify which characteristics or components may be most relevant for practitioners. This would require obtaining program manuals, analyses or other information about program components (if available) to help attribute effectiveness to individual components.

Evidence-informed implications for practice

Parenting programs may be beneficial for a range of outcomes such as improvements in child behaviour, mother-child interaction and maternal responsiveness. Parenting programs are also effective for families experiencing various risk factors such as low socio-economic status or financial stress, and for children with existing SEB difficulties. These types of programs typically include multiple elements, such as vignettes, group discussion, information sessions and other activities. Therefore, it may be possible for practitioners to draw on one or more of these elements to provide tailored support to families to meet their particular circumstances.

Programs delivered by trained professionals show the greatest chance of effecting change. Therefore, organisations may wish to consider providing additional training to practitioners. Alternatively, organisations may prefer to employ specialist practitioners with professional qualifications and training in parenting programs or other programs relevant to their client base. Regardless of organisational options or choices, ensuring that practitioners are sufficiently trained in delivering interventions is necessary to elicit the most favourable outcomes for children and families. Training may include program-specific training where this is appropriate.

Identifying the risk factors children experience may help practitioners choose a type of program most suited to the child's situation. For instance, children with a mother with mental illness may benefit from the mother participating in a parental mental health program, while children of low birth weight may benefit from KMC.

Programs appear to be effective through a range of delivery formats including individual or group, in-home or community. Therefore, practitioners may be able to provide options to families so that families can receive support in a way that is most appropriate to their circumstances and preferences. However, practitioners should ensure that the fidelity of key elements of the program content, strategies and activities is maintained as much as possible to effect favourable outcomes.

These findings suggest that practitioners need to be able to identify the key risk factors for the families they work with where children may be at risk of SEB difficulties. Practitioners may then be able to choose a program, and delivery format, that is most appropriate for the child's and families' needs to ensure the greatest chance of benefit.

Table 1 provides a summary of the key risk factors, possible programs and outcomes included in this review. This table could be useful for practitioners to help guide decisions when choosing programs to match with particular clients/groups or when seeking improvements in particular outcomes.

| Key risk factors/target groups | Possible appropriate programs | Possible outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Children with SEB difficulties | Group-based parenting programs | Reductions in emotional, behavioural and externalising problems |

| Pre-term/low birth weight children | Kangaroo mother care | Improvements in child self-regulation and parent-child interaction |

| Parenting programs - home and group-based settings | Improvements in infant developmental outcomes, child behaviour, mother-child interaction, maternal sensitivity, maternal responsiveness | |

| Children of mothers with mental illness | Parental mental health programs including cognitive behavioural therapy and counselling - individual and group delivery | Improvements in child functioning, mother-infant interaction, mother-infant behaviour during interactions |

| Children and families in other vulnerable circumstances | Parenting programs - delivered in person, via web, individual and groups | Improvements in mother-infant interaction, parental sensitivity, parent-child relationship Reductions in child stress, internalising and externalising behaviours |

| Preschool social-emotional learning programs - delivered in home, school, community | Improvements in social skills, emotional skills Reductions in behavioural problems |

Limitations of using these findings

In considering the findings from this review, the following limitations should be noted:

- No studies targeted fathers. A few studies in the reviews may have included fathers in their samples; however, this information was not clearly or consistently reported. Therefore, findings may not be generalisable to some families.

- Most studies only reported on changes over a short period of time, such as a few months. Therefore, it is not clear how long the benefits from these types of programs last. Monitoring client progress over time, where possible, may be appropriate to determine if additional support is required.

- The included reviews did not consistently report what dose families received of a particular program. That is, it is not clear how many sessions, or length of each session, are required for children and families to receive a benefit. It is possible that some families, experiencing particular or multiple risk factors, may require additional and extended support.

- Finally, this rapid review did not identify core components of programs that may be most supportive of change. This means that it is not possible to identify which characteristics are common across programs or which characteristics of any program are most beneficial.

Conclusion

This review aimed to identify and describe effective prevention and early intervention programs targeting SEB wellbeing during early childhood for children experiencing, or at risk of, SEB difficulties. The findings suggest that different types of programs may be suitable for children and families experiencing different types of risk factors.

The review has identified gaps and limitations in the existing evidence. Greater evidence about programs that are effective when working with fathers, how long programs and individual sessions should run for, and identifying the core elements of programs will be beneficial to practitioners and families.

However, a consistent finding is that parenting programs and programs delivered by trained practitioners are effective in improving a range of social, emotional and behavioural outcomes for children. Additionally, these types of programs appear to be effective with families that experience a range of risk factors. As such, it may be useful for practitioners to become familiar with some available parenting programs and, where possible and appropriate, receive training in delivering these programs or the types of activities they include.

References

- Akbari, E., Binnoon-Erez, N., Rodrigues, M., Ricci, A., Schneider, J., Madigan, S., & Jenkins, J. (2018). Kangaroo mother care and infant biopsychosocial outcomes in the first year: A meta-analysis. Early Human Development, 122, 22-31.

- Athanasopoulou, E., & Fox, J. R. E. (2014). Effects of Kangaroo Mother Care on maternal mood and interaction patterns between parents and their preterm, low birth weight infants: A systematic review. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(3), 245-262.

- Bagner, D. M., Rodríguez, G. M., Blake, C. A., Linares, D., & Carter, A. S. (2012). Assessment of behavioral and emotional problems in infancy: A systematic review. Clinical Child Family Psychology Review, 15, 113-128.

- Barlow, J., Bennett, C., Midgley, N., Larkin, S. K., & Wei, Y. (2015). Parent-infant psychotherapy for improving parental and infant mental health: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 1-223.

- Barlow, J., Bennett, C., Midgley, N., Larkin, S. K., & Wei, Y. (2016). Parent-infant psychotherapy: A systematic review of the evidence for improving parental and infant mental health. Journal of Reproductive & Infant Psychology, 34(5), 464-482.

- Barlow, J., Bergman, H., Kornør, H., Wei, Y., & Bennett, C. (2016). Group-based parent training programmes for improving emotional and behavioural adjustment in young children. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8, CD003680.

- Bieleninik, Ł., Ghetti, C., & Gold, C. (2016). Music therapy for preterm infants and their parents: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 138(3), 1-17.

- Bor, W., McGee, T. R., & Fagan, A. A. (2004). Early risk factors for adolescent antisocial behaviour: An Australian longitudinal study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38(5), 365-372.

- Boustani, M. M., Frazier, S. L., Chu, W., Lesperance, N., Becker, K. D., Helseth, S. A. et al. (2020). Common elements of childhood mental health programming. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Services Research, 47, 475-486.

- Filippa, M., Panza, C., Ferrari, F., Frassoldati, R., Kuhn, P., Balduzzi, S., & D'Amico, R. (2017). Systematic review of maternal voice interventions demonstrates increased stability in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992), 106(8), 1220-1229.

- Goodman, S. H., Cullum, K. A., Dimidjian, S., River, L. M., & Kim, C. Y. (2018). Opening windows of opportunities: Evidence for interventions to prevent or treat depression in pregnant women being associated with changes in offspring's developmental trajectories of psychopathology risk. Development and Psychopathology, 30(3), 1179-1196.

- Grube, W. A., & Liming, K. W. (2018). Attachment and biobehavioral catch-up: A systematic review. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(6), 656-673.

- Hemmi, M. H., Wolke, D., & Schneider, S. (2011). Associations between problems with crying, sleeping and/or feeding in infancy and long-term behavioural outcomes in childhood: A meta-analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 96, 622-629.

- Herd, M., Whittingham, K., Sanders, M., Colditz, P., & Boyd, R. N. (2014). Efficacy of preventative parenting interventions for parents of preterm infants on later child behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(6), 630-641.

- Johnson, C. A., & Katz, R. C. (1973). Using parents as change agents for their children: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 14(3), 181-200. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1973.tb01186.x

- Jones, S. M., Brown, J. L., & Lawrence, A. J. (2011). Two-year impacts of a universal school-based social-emotional and literacy intervention: An experiment in translational developmental research. Child Development, 82(2), 533. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01560.x

- King, V. J., Garritty, C., Stevens, A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Hartling, L., Harrod, C. S. et al. (2017). Performing rapid reviews. In A. C. Tricco, E. V. Langlois, & S. E. Straus (Eds.), Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: A practical guide (pp. 21-38). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Letourneau, N., Dennis, C.-L., Cosic, N., & Linder, J. (2017). The effect of perinatal depression treatment for mothers on parenting and child development: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 34(10), 928-966.

- Letourneau, N., Tryphonopoulos, P., Giesbrecht, G., Dennis, C.-L., Bhogal, S., & Watson, B. (2015). Narrative and meta-analytic review of interventions aiming to improve maternal-child attachment security. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(4), 366-387.

- Lonigan, C. J., & Phillips, B. M. (2001). Temperamental influences on the development of anxiety disorders. In M. W. Vasey & M. R. Dadds (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of anxiety (pp. 60-91). New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Marsenich, L. (n.d.). Using evidence-based programs to meet the mental health needs of California children and youth. Retrieved from www.cibhs.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/ebp_children_youth_070811.pdf

- McLuckie, A., Landers, A. L., Curran, J. A., Cann, R., Carrese, D. H., Nolan, A. et al. (2019). A scoping review of mental health prevention and intervention initiatives for infants and preschoolers at risk for socio-emotional difficulties. Systematic Reviews, 8(1), 1-19.

- Meagher, S., Arnold, D., Doctoroff, G., Dobbs, J., & Fisher, P. (2009). Social-emotional problems in early childhood and the development of depressive symptoms in school-age children. Early Education and Development, 20(1), 1-24.

- Moore, T. G., Arefadib, N., Deery, A., & West, S. (2017). The first thousand days: An evidence paper. Parkville, Victoria: Royal Children's Hospital. Retrieved from www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccchdev/CCCH-The-First-Thousand-Days-An-Evidence-Paper-September-2017.pdf

- Murano, D., Sawyer, J. E., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2020). A meta-analytic review of preschool social and emotional learning interventions. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 227.

- O'Hara, L., Smith, E. R., Barlow, J., Livingstone, N., Herath, N. I., Wei, Y. et al. (2019). Video feedback for parental sensitivity and attachment security in children under five years. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD012348.

- Oh, E., Mathers, M., Hiscock, H., Wake, M., & Bayer, J. (2015). Help seeking for child mental health. Australian Journal of Psychology, 67, 187-195. doi:10.1111/ajpy.12072

- Poulou, M. S. (2015). Emotional and behavioural difficulties in preschool. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 225-236.

- Provenzi, L., Broso, S., & Montirosso, R. (2018). Do mothers sound good? A systematic review of the effects of maternal voice exposure on preterm infants' development. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 88, 42-50.

- Rayce, S. B., Rasmussen, I. S., Klest, S. K., Patras, J., & Pontoppidan, M. (2017). Effects of parenting interventions for at-risk parents with infants: A systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open, 7(12), e015707.

- Rose, S. D. (1974). Using parents as change agents for their children: A review. Social Work, 19(2), 156-162.

- Sanson, A., Letcher, P., Smart, D., Prior, M., Toumbourou, J. W., & Oberklaid, F. (2009). Associations between early childhood temperament clusters and later psychosocial adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 55(1), 26.

- Thanhäuser, M., Lemmer, G., de Girolamo, G., & Christiansen, H. (2017). Do preventive interventions for children of mentally ill parents work? Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(4), 283-299.

- Toumbourou, J. W. (2012). Would a universal check of 3-year-olds prevent or create childhood mental health problems? The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(8), 703. doi:10.1177/0004867412454587

- Toumbourou, J. W., Williams, I., Letcher, P., Sanson, A., & Smart, D. (2011). Developmental trajectories of internalising behaviour in the prediction of adolescent depressive symptoms. Australian Journal of Psychology, 63(4), 214-223.

- Tully, L. (2020). Identifying social, emotional and behavioural difficulties in the early childhood years. Adelaide, SA: Emerging Minds. Retrieved from emergingminds.com.au/resources/identifying-social-emotional-behavioural-difficulties-in-early-childhood

- University of Canberra Library. (2020). Evidence-Based Practice in Health. Canberra, ACT: University of Canberra. Retrieved from canberra.libguides.com/evidence

- US Department of Health and Human Services, & Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2010). Evidence-based clinical and public health: Generating and applying the evidence. Washington D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services, & Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved from www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/EvidenceBasedClinicalPH2010.pdf

- Vasileva, M., Graf, R., Reinelt, T., Petermann, U. J., & Petermann, F. (2020). Research review: A meta-analysis of the international prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in children between 1 and 7 years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1-10. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13261

- Zhang, X., Kurtz, M., Lee, S.-Y., & Liu, H. (2014). Early intervention for preterm infants and their mothers: A systematic review. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Location | International with a primary focus on studies from OECD countries | - |

| Language | English | - |

| Publication date | May 2010 - April 2020 | - |

| Population | Children aged under five years at the time of intervention. Where there is a range of child ages, then the mean age is younger than five years. At risk of SEB difficulties. At risk is defined as being exposed to one or more known risk factors for SEB difficulties or exhibiting SEB difficulties. Parents or primary caregivers of aforementioned children (where child measures are taken) | Children with neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g. intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder) or language/communication disorders Children with diagnosed mental health disorders Studies with unclear participant age ranges |

| Type | Systematic reviews or meta-analyses Early intervention and/or prevention programs aimed at improving child SEB wellbeing Early intervention and/or prevention programs targeting parental or parent-child relationship factors | Interventions targeting parental issues only, with no child SEB outcomes Pharmacotherapy interventions (either child or parent) Generic parenting programs not targeting change in parent-child relationship and/or child's current or future SEB wellbeing Early Childhood Education and Care curriculum-based programs |

| Outcomes of interest | Child outcomes related to SEB wellbeing. Parent-child relationship outcomes measuring the quality of, or changes in, the parent-child relationship that are related to child SEB wellbeing | Outcomes related to parents only, with no child SEB outcomes |

Appendix B: PRISMA flow diagram

Appendix C: Characteristics and findings of included reviews

The table can also be viewed on pages 13–19 of the PDF.

| Author (year) | Intervention/ program type | Target group | Provider | Setting and delivery method | Program aim | Targeted outcomes with effectiveness | Other outcomes measured (no evidence of effectiveness) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early or existing SEB difficulties | |||||||

| Barlow, Bergman et al. (2016) | Parenting programs | Children with early/existing emotional or behavioural problems; Universal Children aged up to 3 yrs 11 mths | Range of professionals, including trained providers, psychologists, nurses and social workers | Setting: Mainly community settings (e.g. community-based agencies, medical centres). Some NR. Mode: Group-based Duration: 1 wk to 7 mths Session length: 1 to 2.5 hrs (or NR) | To investigate whether group-based parenting programs are effective in improving emotional and behavioural adjustment of young children |

|

|

| Pre-term/low birth weight infants | |||||||

| Akbari et al. (2018) | Kangaroo Mother Care | Pre-term/low birth weight infants Child age NR but age at outcomes 0 to 52 weeks | NR | NR | To investigate the relationship between KMC and biopsychosocial outcomes for infants/toddlers |

|

|

| Athanasopoulou and Fox (2014) | Kangaroo Mother Care | Pre-term/low birth weight infants GA ≤37 wks | NR | Setting: NR Duration: 3 days to 3 mths (or NR) Session length: 20 mins to 24 hrs (or NR) | To investigate whether KMC can reduce negative psychological effects associated with pre-term birth through improving maternal mood and/or fostering more positive infant-parent interactions |

|

|

| Bieleninik et al. (2016) | Music therapy | Pre-term infants GA + chronological age of 27 to 47 wks | Trained music therapist (provided either intervention or consultation) | Setting: Hospital, community or home Duration: 2 to 14 days (or until discharge) No. sessions: 1 to 9 (or until discharge) Session length: 8 to 60 mins | To investigate the effect of music therapy on a range of outcomes for pre-term infants and their parents during NICU hospitalisation and post-discharge |

|

|

| Filippa et al. (2017) | Maternal voice interventions | Pre-term infants Average GA at birth of <32 wks or GA at birth of <32 wks | NR | Setting: Neonatal intensive care unit Duration: 1 day to discharge at several weeks Session length: A few seconds to 45 mins | To review literature on the effectiveness of maternal voice interventions for supporting pre-term infant outcomes during NICU hospitalisation |

|

|

| Herd et al. (2014) | Parenting programs | Pre-term infants Child age NR, but intervention from birth | Trained providers, including nurses, physiotherapists and psychologists | Setting: Varied (e.g. home, day-care centre, child development centre) Mode: Varied. Included home-based and group-based Duration: 3 mths to 3 yrs | To investigate the effectiveness of parenting programs for parents of pre-term infants for improving child behaviour |

| |

| Provenzi et al. (2018) | Maternal voice interventions | Pre-term infants GA + chronological age of 23 to 36 wks | NR | Setting: Neonatal intensive care unit Mode: Maternal voice (live or recorded) Duration: 24 hrs to 6 wks (or NR) Session length: Recorded voice - <1 min to 16 hrs; Live - 1 to 16 hrs | To investigate the effectiveness of maternal voice interventions in the NICU on the development of very pre-term infants |

|

|

| Zhang et al. (2014) | Parenting programs | Pre-term infants Average GA of 27 to 33 wks | Range of professionals, including psychologists, nurses and researchers | Setting: Neonatal intensive care unit; Home (post-discharge) Duration: 1 wk post-discharge to corrected age of 60 wks No. sessions: Home-based - 1 to 6 visits; NICU-based - 1 visit to weekly visits | To investigate the effectiveness of early interventions for pre-term infants in relation to infant, maternal, and maternal-infant outcomes |

| |

| Children of parents with a mental illness | |||||||

| Goodman et al. (2018) | Parental mental health interventions | Children of parents with a mental illness (mothers with depression) Mean age 6.65 mths (SD = 17.68) | NR | NR | To review the effectiveness of interventions to prevent or reduce depression in pregnant women on outcomes for their infants (neurobiological and behavioural) |

|

|

| Letourneau et al. (2017) | Parental mental health interventions | Children of parents with a mental illness (mothers with antenatal/postpartum depression) Child age NR | Largely NR, but included trained therapists, a psychologist and a nurse | Setting: Home, clinic or NR Duration: Typically 8 to 12 wks Session length: Typically 60 to 90 mins | To investigate the effectiveness of various maternal perinatal depression interventions on parenting and child outcomes |

| |

| Thanhäuser et al. (2017) | Parent-infant dyadic interventions | Children of parents with a mental illness (mothers with past/current mental health disorder) Child age range = 0 to 4 yrs, mean 0.7 mths | Trained professionals, such as nurses and psychologists | Setting: Home, clinic or NR Mode: Varied. Included family-based, group-based, mother only or NR Session length: 15 to 300 mins | To investigate the efficacy of preventative interventions for infants and children of parents with a mental illness (separate analyses for mother-infant and child/adolescent interventions) |

| |

| Children or families in other vulnerable circumstances | |||||||

| Barlow et al. (2015); Barlow, Bennett, Midgley, Larkin, and Wei (2016) | Parent-infant dyadic interventions (parent-infant psychotherapy) | Children exposed to vulnerability (e.g. maltreatment, parental mental health problems, attachment problems) Child age 8 wks to 30 mths | Parent-infant psychotherapist/specialist | Setting: Varied (e.g. home, research clinic, child mental health centre, mother-baby prison units or NR) Mode: In-person. All studies delivered to individual dyads except for one group-based study Duration / No. sessions: Ranged from 8 sessions to between 46 and 49 wks | To investigate the effectiveness of parent-infant psychotherapy (PIP) in improving infant/parental mental health and the infant-parent relationship |

|

|

| Grube and Liming (2018) | Parenting programs | Current/past child welfare involvement Child age 3.6 to 69.6 mths | Trained parent coaches, including social workers, psychologists, psychiatric nurses and child psychiatrists | Setting: Home Mode: Face-to-face Duration: 10-week program | To review literature and evidence on Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) to determine its effectiveness |

|

|

| Letourneau et al. (2015) | Parenting programs | Children of mothers with vulnerability (e.g. financial stress, maltreating) Child age ≤36 mths | NR with exception of trained health care provider in one study | Setting: Home or NR Mode: Varied. Included home visits, video feedback, psychoeducation and written materials Duration: 9 wks to 2 yrs (or NR) Session length: 1 to 2 hrs (or NR) | To investigate the effectiveness of interventions that focus on maternal sensitivity or maternal reflective functioning on mother-infant attachment security and other infant/maternal outcomes. |

|

|

| Murano et al. (2020) | Preschool social-emotional learning programs | Mainly children exposed to vulnerability (e.g. low SES, minority group) or children with SEB difficulties; Universal Child mean age 4.31 yrs | Trained providers, including researchers, teachers and parents | Setting: Varied (e.g. home, school, community centre) Mode: In-person | To investigate the effectiveness of social and emotional learning interventions (SELs) on SEB outcomes for preschool children in targeted (i.e. selective and indicated) and universal settings |

| |

| O'Hara et al. (2019) | Parenting programs | Children exposed to vulnerability, specifically problems impacting (or at risk of impacting) attachment and parental sensitivity Child age <5 yrs | Largely NR, but included therapists, nurses and video feedback professionals/coaches | Setting: Varied (e.g. home, family centre, hospital outpatient/inpatient) Mode: In-person video feedback. Some added structured teaching tasks or handouts/booklets. Duration: 1 visit to 12 mths (or NR) No. sessions: 1 to >10 sessions | To investigate the effects of video feedback on attachment security, parental sensitivity and parental reflective functioning in young children at risk of poor attachment |

|

|

| Rayce et al. (2017) | Parenting programs | Children of families exposed to vulnerability (e.g. poverty) Child age 0 to 12 mths | NR | Setting: Home or outside home Mode: In-person (individual, group, both); Web coaching Duration: ≤6 to ≥24 mths Session length: 45 to 180 mins (or NR) No. sessions: 8 to 41 (or NR) | To review the effects of parenting interventions for infants of at-risk families |

|

|

Notes: NR = not reported; GA = gestational age.

This resource has been co-produced by CFCA and Emerging Minds as part of the National Workforce Centre for Child Mental Health. The Centre is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health under the National Support for Child and Youth Mental Health Program.

At the time of writing, Michele Hervatin was a Senior Research Officer at the Australian Institute of Family Studies. Dr Trina Hinkley is a Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Cathryn Hunter, formerly a Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies, contributed to the initial literature search, selection and data extraction.

Featured image: © GettyImages/danchooalex

978-1-76016-233-7