Bystander approaches

Responding to and preventing men's sexual violence against women

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

May 2014

Download Practice guide

Overview

Bystander action is often promoted as an effective way of engaging non-violent men in challenging violence against women in their peer groups and communities. While there is much international research literature examining the barriers and facilitators to bystander action, and several program models well evaluated in the United States, bystander approaches for responding to and preventing sexual violence against women are far less developed in Australia. Australian research, policy and programs are increasingly focused on harnessing bystander action as part of a holistic plan to address and prevent violence against women, including sexual violence. Yet there are some unresolved challenges and issues in their implementation.

Key messages

-

Bystander approaches seek to build shared individual and community responsibility for responding to and preventing sexual violence by encouraging people not directly involved in violence as a victim or perpetrator to take action. As such, they potentially have a key role to play in challenging cultures of violence and gender inequality.

-

Many Australian violence education and prevention programs already include some bystander elements, such as how to care for a friend who has experienced violence, or what to do when witnessing or becoming aware of an incident of violence against women.

-

Individuals are most likely to take positive action to respond to or prevent violence when they feel supported to do so by their peers, communities, and organisations (such as schools and workplaces), when they feel confident in their ability to take action, and when they perceive that their action will make a positive difference.

-

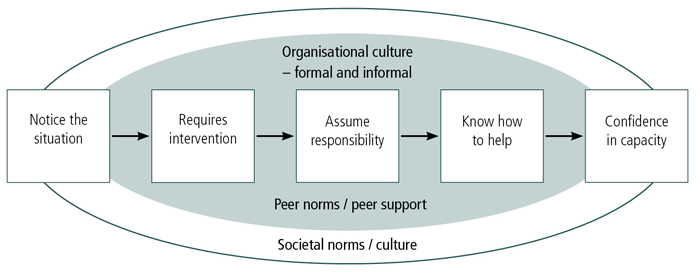

Individual bystander action requires noticing the situation; interpreting the event as requiring intervention; assuming responsibility; deciding how to help; and confidence in the capacity to help (Darley & Latane, 1968).

Introduction

The potential to engage bystanders in actively responding to and preventing sexual violence is currently gaining momentum in public policy and program development in Australia. The conditions that enable an individual witnessing a crime to take action to intervene in order to prevent harm to another person have long been of interest within the fields of crime and violence prevention generally. Yet the idea to "bring in the bystander" has really come into its own through research and programs directed at responding to and preventing violence against women. Much international research, as well as education and program resources, have been directed at encouraging individuals to take action to support a victim or challenge a perpetrator of violence, to intervene in situations where violence is likely to occur, and to disrupt peer cultures condoning of violence against women - particularly sexual violence. However bystander approaches are by no means a panacea, and there are some unresolved challenges and issues to be addressed if the full potential of bystander action is to be realised.

Bystander interventions and preventing sexual violence

Definitions and rationale

Simply put, and for the purposes of this paper, a bystander is anybody who becomes aware a behaviour, or situation where sexual violence has the potential to occur, is occurring or has occurred (see Potter, 2012, p.283). Within crime prevention, and much psychological research, the terms "active" and/or "pro-social" bystander are commonly used to refer to the individual who intervenes or takes action in response to the observed situation. By contrast, "passive" bystander refers to individuals who observe a situation and fail to intervene or take action in some way.

There are a variety of actions that a pro-social bystander can take to either respond to or prevent sexual violence against women. While some forms of bystander action are intended to stop violent behaviours at the moment they are occurring (intervention); others are intended to prevent violence recurring or reduce the impacts of violence that has occurred (tertiary prevention) or to address a situation where there is a heightened risk of violence occurring (secondary prevention); and finally, some are intended to challenge the social norms and attitudes that perpetuate sexual violence in the community (primary prevention). For example, bystander action may involve:

- Intervention - Intervening to stop an incident of sexual violence that is occurring, by calling the police, reporting the incident to security or an authority figure (such as a teacher in a school, or a manager at a workplace).

- Tertiary prevention - Supporting a victim or confronting a perpetrator, so as to respond to the physical, psychological and social harms of sexual violence, by validating their disclosure of an incident (or following up with them after having witnessed an incident) and assisting them to make contact with appropriate support services.

- Secondary prevention - Recognise and address a situation where there is a heightened risk of violence occurring, such as keeping an eye out for the safety of friends, peers, colleagues or family members and being aware of, and taking action in response to, what is happening in one's surroundings (such as offering to take a drunk friend home).

- Primary prevention - Strengthening the conditions that work against violence occurring, by promoting gender equity and challenging sexist, discriminatory, violence-supportive attitudes and behaviours in peer groups, organisations (such as schools, universities, and workplaces) and in communities. Examples might include: challenging a friend on their use of sexist slang, expressing discontent with a colleague for telling a sexist joke, or getting involved in a review of hiring and promotion practices at work or at a local community group.1

The primary rationale behind engaging bystanders to take action to respond to and/or prevent sexual violence is premised on a shared community responsibility to do so. This is a reaction against much rape prevention programming (primarily in the US) which teaches women "rape avoidance" strategies, and by implication, reinforces women's responsibility for managing men's sexuality and circumventing sexual violence (see Schewe & O'Donohue, 1993; Ullman, 1997; 2007 for a review). Bystander programs, by contrast, work against negative, victim-blaming norms and rape myths, which have proven very resistant to change, by identifying the actions that we can all take everyday to prevent sexual violence, support victims, and challenge cultural norms condoning rape.

Moreover, among young people of school and university age in particular - those who are most at risk of experiencing and perpetrating sexual violence (see for example, Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2013; Mouzos & Makai, 2004; Heenan & Murray, 2006) - there is much to be gained by strategies that support and empower all individuals to take action rather than to allow sexual violence and violence-supportive cultures to go unchallenged in their peer groups and communities. When considered alongside survey data that repeatedly shows that victims of sexual violence are unlikely to report the incident to police (ABS, 1996; 2006; 2013), and are most likely to first confide in a friend or family member (see Mouzos & Makai, 2004) - then it also makes sense to educate and skill individuals to respond appropriately to disclosures of sexual violence.

Finally, using bystander approaches to engage a broader audience in a conversation about sexual violence and its prevention, may promote greater "readiness for change" or receptivity to prevention messages that can be harnessed by further education and programs (see Banyard & Moynihan, 2011). In other words, rather than addressing program participants as only potential perpetrators or potential victims, one of the principles of a bystander approach to preventing sexual violence is to "transcend the limitations of the perpetrator-victim binary" (Katz, Heistercamp, & Fleming, 2011, p. 685) by providing a more positive role and identity for participants that may in turn decrease resistance, defensiveness, or backlash (Amar, Sutherland, & Kesler, 2012). When used in this way it is particularly important to frame bystander approaches as one component, or strategy, in a coordinated set of efforts directed at preventing men's sexual violence against women (see Katz et al., 2011).

There is much debate and critique about the usefulness of the term "bystander" in relation to sexual violence and its prevention. For example, some scholars take issue with the implied innocence or externality of the "bystander" (see Levy & Ben-David, 2008; Berkowitz, 2009); when much feminist theorising of violence against women and its causes implicates us all in the reproduction of gender norms, attitudes, and inequality that are ultimately responsible for violence (see Katz et al., 2011; McCarry, 2007; Pease 1995; 2008). As such, there are no "bystanders" to a culture that condones or facilitates sexual violence against women.

It is acknowledged in this paper that there are risks with framing sexual violence prevention in ways that potentially minimise men's individual responsibility for that violence, and ignores men's collective participation in the reproduction of gender inequality (see Pease 2008 for an overview). The term bystander nonetheless has some usefulness as a concept that is relatively understood within communities, promotes a shared community-level responsibility for violence prevention, and is increasingly gaining traction in policy and prevention circles. For example, as Jackson Katz, founder of Mentors in Violence Prevention, explained:

A bystander means essentially anyone who plays some role in an act of harassment, abuse, or violence but is neither the perpetrator nor the victim … it does not imply what action they have taken or failed to take. That requires an adjective to modify the noun, which is why in [Mentors in Violence Prevention] we speak of "empowered" or "proactive" bystanders versus "passive" ones. (Katz et al., 2011, p. 686-687)

Origins of bystander approaches

Much of the earliest academic research theorising bystander action/inaction in response to acts of violence occurred after the Second World War and in the wake of the Holocaust. Worldwide, researchers were anxious to explain the altruistic actions of so-called "rescuers" as well as the widespread failure of individuals to intervene to prevent the perpetration of gross inhumanities including genocidal violence and persecution. Some of the most striking research findings in relation to bystanders from this period are those identifying the prevalence of individuals' conformity to peer-group norms and pressures (e.g., Asch, 1956; Schachter, 1951) and obedience to perceived authority or leadership (Bandura, 1973; French & Raven, 1959; Milgram, 1974). Similarly, the positive influence of group norms is thought to play a role in the proactive behaviour of "rescuers". Those who do take steps to intervene are often conforming with the proactive norms of a particular group or community to which they belong (see Suedfeld, 2000).

By the 1960s and throughout the 1970s crime and violence research in the United States in particular turned to issues closer to home and was influenced by a number of high-profile cases of bystander "failure" to intervene. Perhaps the most famous of these was the case of Kitty Genovese. Catherine (Kitty) Genovese was raped and murdered 13 March 1964, outside of her Queens (New York, US) apartment, where it is alleged up to 38 neighbours witnessed or overheard the attack, but failed to call the police or intervene to prevent the murder (Rosenthal, 1964).

Such incidents have led to much research into the motivations and decision-making of passive and active bystanders. Foremost among these studies is Darley and Latané's (1968) much cited work which theorised that in group settings, the responsibility for intervening was diffused among the bystanders present, such that individuals were less likely to feel responsible for taking action, and were more likely to think that somebody else may intervene or had already called for help. Ongoing research into this apparent trend in "non-responsive" bystanders, has led to a focus on the factors or situations where individuals are more likely to intervene or, in other words, to act as a "pro-social" bystander. Indeed, much research has described the process through which an individual decides whether to act as a pro-social bystander (see Clarke, 2003; Darley & Latane, 1968; Dovidio, Pilavin, Schroeder, & Penner, 2006, for a review). For example, after first noticing what is happening, a bystander must secondly decide whether the incident is a problem where intervention is needed; thirdly, whether they should take individual responsibility; fourthly, what specific actions to take; and finally, be confident that they have the skills or capacity to take action safely.

At each of these five stages there are numerous barriers and facilitators to an individual deciding to take positive action as a bystander. Put simply, individuals may hold attitudes that minimise forms of sexual violence and thus not notice situations where sexual violence may occur, and/or fail to interpret the event as requiring intervention. Individuals may similarly hold attitudes that place blame on victims of sexual violence, and/or emphasise individual rather than "outsider" responsibility for preventing rape, and thus not assume responsibility to take action. Finally, individuals' may want to take action, but feel uncertain of how to help or that doing something will result in a positive outcome (see Banyard & Moynihan, 2011; Casey & Ohler, 2012).

Each of these attitudinal elements (knowledge of continuum of sexual violence, rape myths and victim-blaming, community and societal responsibility to prevent sexual violence, skills and confidence in taking action) are readily amenable to an educative, and skills-based program. Yet as a model for guiding program development in sexual violence prevention, Darley and Latanes' original theory misses two important components: the role of peer norms (especially male peer norms/support for sexual violence, see Banyard, 2011; Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Schwartz, DeKeseredy, Tait, & Alvi, 2001), as well as organisational cultures and settings (see VicHealth, 2012). Recognising these limitations, recent developments in bystander research have emphasised an ecological model to guide future program development (see Banyard, 2011; McMahon & Banyard, 2012; VicHealth, 2012), and it is to this model for bystander approaches to sexual violence prevention that I now turn.

Bystander approaches to sexual violence prevention: An ecological model

In addition to individual-level barriers and facilitators to bystander action, recent research has sought to highlight the importance of peer norms, organisational cultures and settings, as well as societal-level norms and culture. Such an approach draws on an ecological model - influential in policy and programs preventing violence against women generally (see Heise, 1998; VicHealth, 2007) - which recognises the effectiveness of directing health promotion (or in this case violence prevention) across individual, community/organisational, and societal levels of intervention.

Drawing on an ecological model to frame bystander approaches, as depicted in Figure 1, better captures the influences beyond an individuals' decision-making process as to whether or not they take action.

Figure 1: Ecological model for bystander action to prevent sexual violence

Peer culture supports action

In their highly influential theory of male peer support for violence against women, Schwartz and DeKeseredy (1997) highlighted the key role that collective peer norms play in enabling violence to varying degrees in particular settings and/or communities (such as the college campus). Norms such as aggressive expressions of masculinity, objectifying or promoting a lack of empathy towards women, or minimising the harm and/or seriousness of sexual violence contribute to a heightened culture condoning of individual men's use of sexual violence against women. In addition, such norms reduce the likelihood that individuals will intervene in sexually violent situations or challenge the violent behaviours of male peers. Indeed, in their surveys of campus sexual assault, Schwartz and DeKeseredy (1997) have repeatedly found that rates of sexual violence are higher on those campuses where there is male peer norm support for the use of coercion in sexual relationships. Recent research, such as by Carlson (2008), has further demonstrated that a key barrier to men taking action as bystanders to prevent sexual violence and harassment is a concern that their action will have social costs, particularly in relation to masculinity and their status in the peer group.

Organisational culture formally and informally supports action

The VicHealth (2012) report More than Ready highlighted the significant role of organisational policy and culture as a facilitator or barrier to an individual taking action as a bystander to violence against women. In a representative survey conducted with the Victorian community, research commissioned by VicHealth found that individuals were most likely to take action to challenge sexism, discrimination and/or violence against women when they felt that their organisation (such as a workplace or sports club) was supportive of doing so. Additionally, there was strong community support for the role of organisations to be leaders in the prevention of sexism, discrimination, and violence against women.

Societal norms support action

Many analyses of factors associated with sexual and intimate partner violence identify the broader societal issues - such as gender inequality and norms supporting male violence and entitlement - that contribute to men's violence against women (VicHealth, 2007; World Health Organization [WHO], 2002; WHO & Butchart, 2004). For example, similar to male peer support theory, Fabiano and colleagues (2003) found that individual college men's intention to take action to challenge norms condoning sexual violence was predicted by their views of the extent to which others held social norms supporting intervention. In addition, in research and evaluation of bystander approaches, Banyard, Plante, and Moynihan (2004) noted the importance of bystander models that are embedded "within ecological and feminist models of the causes of sexual violence calling for broader community approaches that target both men and women and move beyond individual levels of analysis" (p. 69).

Importantly then, bystander approaches to preventing sexual violence require program development that builds individuals' knowledge (what is sexual violence, harassment and sexism? How are they connected?); commitment (sexual violence, harassment and sexism are problems I will help to prevent); capacity (I know what I would do and what I would say when witnessing a situation); and confidence (I feel certain that my action would have a positive outcome and that I would have the support of my peers/family/colleagues). However, they must also be supported by a broader strategy which both promotes widespread social norms supporting bystander intervention, whilst also continuing to address the institutional bases of gender inequality.

1 While the distinction is conceptually important, as noted by VicHealth (2007) and others (see Sutton, Cherney, & White, 2013), it is not always possible to draw clear boundaries around these different categories of intervention and prevention. Furthermore, in practice, many bystander programs are directed at encouraging individuals to take action across each of these different levels of intervention and/or prevention. It would be counter-productive and arguably unethical in some settings, such as the workplace for example, to encourage individuals to challenge sexism and discrimination, if there are not also measures in place to respond appropriately to others' disclosures of these experiences that might be raised by such bystander action.

What do successful bystander programs look like?

With the rationale and ecological framework for bystander approaches to sexual violence prevention in mind, I now turn to consider examples of "successful" programs across three key areas: public education campaigns, programs with (college-age) young people, and incorporating a bystander component into sexual violence education programs in high schools.2 The programs described have been selected as either well-known examples, or in some cases (such as "Bringing in the Bystander") well-developed and evaluated program examples. I then go onto summarise what we know about successful practice in sexual violence prevention generally, and how this relates to bystander approaches.

Examples of public education campaigns

The public campaigns of the White Ribbon Foundation are perhaps the most well known of bystander campaigns against men's violence against women in Australia. White Ribbon Day began in Canada in 1991, on the second anniversary of one man's massacre of 14 women in Montreal. A group of men started the campaign to encourage others to speak out against violence against women. White Ribbon Day awareness-raising campaigns and activities have since been promoted in many countries internationally. In 1999 the United Nations' General Assembly declared 25 November the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and the white ribbon was adopted as the international symbol for the day. In Australia, the federal Office for Women began to run awareness-raising activities in 2000, and in 2003 the day became a national campaign, as a partnership with UNIFEM and men's organisations.

The current Australian White Ribbon Day campaign draws on a number of high-profile male ambassadors from across media, sport, business, government and other sectors, and promotes the taking of an oath: men swearing "never to commit, excuse or remain silent about violence against women". The campaign also incorporates television, radio and print media advertising, as well as sponsoring various activities and events to promote the message of "men - not violent, not silent". The campaign materials are specifically targeted at engaging non-violent men through a positive message of men's role as active bystanders against violence.

A rare example of a specific media campaign directed at engaging individuals as bystanders was the 2005 White Ribbon Day television advertisement, Lend a Hand, developed pro bono by Saatchi and Saatchi Sydney with the support and sponsorship of UNIFEM.3 The advertisement featured a couple eating a meal in their apartment as they listen to a man next door verbally abusing a woman. It becomes apparent that the abuse has become physical when a painting almost falls off their apartment wall. The man picks up a baseball bat, walks into the corridor and knocks on his neighbour's door. The door opens. "You might be needing this", he says, handing the baseball bat over to the abusive man. The advertisement closes with the provocative text: "Do nothing and you may as well lend a hand". While the advertisement's use of exaggeration was potentially controversial, it nonetheless problematised the role of inactive bystanders in contributing to a society where violence against women by some men goes largely unchallenged by others.

However the impact of a provocative media resource such as Lend a Hand is likely to be limited to one of raising awareness of the issue of individual inaction against men's violence - without actually following up with any educative content on what action a bystander could take. So for example, a series of follow-up clips, each depicting an alternative ending to the scenario (with the couple taking different courses of action), and demonstrating the positive difference made by their action as pro-social bystanders would greatly enhance the educative potential of such a campaign.

Men Can Stop Rape (US)

Men Can Stop Rape is an international organisation that seeks to mobilise men to create cultures free from violence, especially men's violence against women. Since its inception in 1997, Men Can Stop Rape has called on men to redefine masculinity and male strength as part of preventing men's violence against women. Men Can Stop Rape is involved with train-the-trainer programs, running workshops with young men (16-session "Men of Strength" clubs), and social marketing campaigns, all directed to promoting men's involvement as pro-social bystanders to prevent sexual and intimate partner violence. Organised around the theme line "Where Do You Stand?" (see Box 2 below), the current campaign consisting of posters, radio and theatre advertisements seeks to:

- educate young men about their role as allies with women in preventing sexual and intimate partner violence;

- promote positive, non-violent roles for men; and

- empower youth to take action to end sexual and dating violence, promote healthy relationships based on equality and respect and create safer communities (see <www.mencanstoprape.org>).

While a detailed evaluation of the impact of campaign materials is not yet publicly available, Men Can Stop Rape has certainly been influential in the US, with over 100 examples of "Men of Strength" (MOST) clubs emerging across high schools and communities, and campaign materials and peer training resources being packaged specifically for use with young people in community, high school and college settings.

Box 2: Men Can Stop Rape - Where Do You Stand? campaign

- When Karl kept harassing girls on the street, I said: "Stop being a Jerk". I'm the kind of guy who takes a stand. Where do you stand?

- When Jason wouldn't leave Mary alone, I said: "Let it go". I'm the kind of guy who takes a stand. Where do you stand?

- When Kate seemed too drunk to leave with Chris, I checked in with her. I'm the kind of guy who takes a stand. Where do you stand?

Source: Men Can Stop Rape (n.d.)

Examples of bystander education programs with young people

In their review of bystander approaches to preventing violence against women, Banyard and colleagues (2004) noted that "the research literature focuses much more on explaining and describing bystander behaviour than on developing effective interventions to promote it" (p. 69). It is indeed the case that there is a dearth of well-documented and rigorously evaluated bystander programs. However, there are some standout programs that serve as useful models for the development of bystander approaches here in Australia.

Bringing in the Bystander (US)

- Developed by Banyard and colleagues at the University of New Hampshire, Bringing in the Bystander draws on a community of responsibility model to teach bystanders how to intervene safely and effectively in cases where sexual violence may be occurring or where there may be risk. The key message of the program is that "everyone in the community has a role to play in ending sexual violence". The program includes both women and men as potential bystanders or witnesses to risky behaviours related to sexual violence around them.

- The program is based on a multi-session curriculum conducted in groups with a team of one male and one female peer facilitator. Using an active learning environment, participants learn about the role of pro-social bystanders in communities and information about sexual violence, as well as learning and practising appropriate and safe bystander skills.

- Bringing in the Bystander has been evaluated on the campus of the University of New Hampshire, and while evaluation is ongoing, the results demonstrate the effectiveness of this program in terms of increasing student participants' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours about effective bystander responses to sexual violence (see Banyard, Plante, & Moynihan, 2005).

Know Your Power: Step In, Speak Up (US)

Developed by Banyard and colleagues' Know Your Power: Step In, Speak Up is a social marketing campaign designed to compliment and extend the in-person education program Bringing in the Bystander. Know Your Power is delivered to a vastly greater audience through various advertising and awareness-raising resources.

An evaluation of the campaign showed that participants who reported seeing the campaign materials exhibited greater awareness of the violence against women and greater willingness to participate in actions aimed at reducing violence compared to those students who reported not seeing the posters. Campaign messages were displayed on campus via posters, bookmarks, bus advertisements, computer screen pop-up images, and campaign products (such as water bottles). The campaign invites university students to think about violence against women on campus and to consider actions to prevent it, representing an important step in reducing sexual violence on campuses where prevailing norms and culture too often facilitate rather than discourage sexual violence. The bystander-oriented social marketing campaign explicitly modelled pro-social bystander behaviour through a series of scenarios that illustrated typical university contexts (See example in Box 3). One poster shows a young man forcing a young woman up against the desk in her dorm room as she exclaims that he is hurting her. Outside the room, two fellow student residents discuss how to intervene. Another poster features students listening to and caring for friends who have experienced sexual violence. All the scenarios feature the campaign tagline "Know your power. Step in, Speak up. You can make a difference", and provide specific advice about what to do in a situation similar to the one shown. For example, the first poster above offers the following advice: "Intimate partner abuse is everyone's problem. Intervene when you see it or hear it" and shows the students agreeing to report the incident to an authority (Potter, 2012).

Box 3: Bringing in the Bystander - Know Your Power campaign

Scenario: Three college-age men are standing around a bucket of alcoholic punch:

- Man 1: I'm gonna get Kali so wasted that she can't say no.

- Man 2: That's messed up. If you're going to do that you need to leave now.

- Man 3: If you want to get with a girl, that's not the way to do it.

Tagline: Alcohol is the #1 date rape drug. Don't let anyone use alcohol to commit sexual assault. Know Your Power, Step In, Speak Up. You Can Make a Difference.

Source: Prevention Innovations, University of New Hampshire (2011)

Mentors in Violence Prevention (US)

Under the leadership of anti-violence educator Jackson Katz and located at Northeastern University's Centre for the Study of Sport in Society, the Mentors in Violence Prevention program is a peer education/leadership training program that motivates student-athletes and student leaders to play a central role in preventing violence against women. Founded in 1993, the Mentors in Violence Prevention program views student-athletes and student leaders not as potential perpetrators or victims, but as empowered bystanders who can interrupt and challenge sexist and abusive attitudes and behaviours among peers (Katz et al., 2011). The program includes a multi-session (six or seven 2-hour sessions) curriculum in which participants:

- explore different forms of abuse;

- explore the socialisation of gender roles in media and society;

- learn to recognise tacit acceptance of violence against women; and

- practise skills in how to confront sexist behaviour and attitudes.

The program also includes an additional train-the-trainer component for those participants who are interested in becoming further involved as peer educators. Ongoing program evaluation demonstrates promising results in relation to changes in participants' knowledge and behaviours (Ward, 2001).

Incorporating a bystander component in sexual violence education

Sexual Assault Prevention Program for Secondary Schools (Australia)

Initially developed by CASA House (the Centre Against Sexual Assault) in Melbourne in 1999, the program involves a whole-of-school approach to preventing sexual assault and promoting respectful behaviours (Imbesi, 2008; Imbesi & Lees, 2011). While not exclusively a bystander program, the student curriculum discusses issues such as defining and understanding consent, identifying respectful and non-respectful behaviours and engaging students as active bystanders - including how to help a friend and access support. Delivery of the curriculum also incorporates many elements of best practice, including:

- involving whole year levels (rather than selected groups);

- a comprehensive program across six sessions;

- an interactive workshop atmosphere with a mix of specially trained staff and community agency guest speakers (rather than didactic learning);

- separate gender groups at first, with mixed gender discussion in later sessions;

- mixed gender co-facilitators; and

- a peer leader/educator component.

Reflecting on the success of the program as it has developed, CASA House staff also suggested that having commitment from the school principal and senior staff, in addition to the whole-of-school community approach adopted, significantly adds to the student program's effectiveness. Furthermore, with staff development and support from CASA House, some schools have been able to further embed the student program into the school curriculum, sustaining the overall program for the long term (Imbesi 2008; Imbesi & Lees, 2011).

Sex & Ethics (Australia)

Another leading exemplar of effective Australian practice in community-based primary prevention through education is the New South Wales-based Sex & Ethics program. Developed by Australian scholar Moira Carmody in partnership with the New South Wales Rape Crisis Centre, the program engages young people in building knowledge and skills about ethical decision-making in their sexual encounters. While not its core focus, Sex & Ethics also includes a bystander component; "Being an Ethical Friend and Citizen" (Carmody, 2009).

Much like the CASA House student curriculum, the Sex & Ethics program incorporates elements of recognised best practice including:

- a comprehensive 6-week program piloted and evaluated with young people aged 16 to 25;

- interactive workshop discussions including a focus on skill development rather than information only; and

- a program structure that emphasises young people's critical reflection on their own sexual practices.

One of the most innovative and promising aspects of the program structure is that rather than merely instructing young people on "what not to do" or the "risks" of sex, the Sex & Ethics program invites young people to further develop their own capabilities to negotiate consensual, ethical, sexual encounters (Carmody, 2009).

Best practice principles for bystander programs to respond to and prevent sexual violence

The international and national research evidence regarding the prevention of violence against women (including bystander approaches) further suggest a number of features for effective practice which are transferable across different settings and prevention approaches including bystander approaches (see Carmody et al., 2009; Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Dyson & Flood 2008; McDonald & Flood, 2012, for comprehensive reviews). For example, in their review of sexual violence prevention, Casey and Lindhorst (2009) also identified:

- comprehensiveness: utilising multiple strategies designed to initiate change at multiple levels of analysis (e.g., individual, peer and community), and for multiple outcomes (e.g., attitudes and behaviour);

- community engagement: partnering with community members in the process of identifying targets for change and designing accompanying changes strategies;

- contextualised programming: designing intervention strategies that are consistent with the broader social, economic and political context of communities;

- theory-based: grounding intervention design in sound theoretical rationales;

- health and strengths promotion: simultaneously working to enhance community resources and strengths while addressing risk factors; and

- addressing structural factors: targeting structural and underlying causes of social problems for change rather than individual behaviour or "symptoms" of larger problems.

These principles to guide program development are further reiterated by McDonald and Flood (2012, see Box 4), who also highlighted the importance of planning for evaluation of bystander programs, a point taken up further in the discussion below. Many of the example programs described above are reflective of these best practice principles, albeit to varying degrees. For example "Bringing in the Bystander", which is perhaps the most rigorously evaluated of these program examples and has been in operation for a decade, draws on a feminist ecological theoretical model and is based on comprehensive empirical research which continues to inform program development targeting both attitudinal and behavioural change (see Banyard, 2011; Banyard, Eckstein, & Moynihan, 2010; Banyard et al., 2004; 2005). The program has been adapted for use at various university campuses in the US in which the program developers work with the college community to refine the program materials for the local context. Though, as Banyard (2011) noted, there is still further work to be done in bystander approaches to take them beyond the level of individual and community change and to incorporate broader structural levels of analysis and action.

Box 4: Principles for developing and implementing bystander approaches

- Design comprehensive programs, using multiple strategies, settings and levels.

- Develop an appropriate theoretical framework.

- Incorporate educational, communication and other change strategies.

- Locate bystander approaches in the relevant context.

- Include impact evaluation in the bystander approach.

Source: McDonald and Flood (2012).

2 It is worth noting that much of the development of bystander programs for college-age young people has taken place in the US, where federal government funding to universities requires that institutions offer sexual violence prevention programming. This is in response to a public acknowledgement of the scale of sexual violence among young people, and particularly on college campuses. While the Australian context is somewhat different, and care must be taken when adapting programs from one location to another, there is arguably value in considering some of the long term and evaluated program examples available.

3 An archived version of the Lend a Hand advertisement is available on YouTube <www.youtube.com/watch?v=AvBKlBhfgPc>

Challenges in implementing bystander approaches to responding to and preventing sexual violence

Bystander approaches to responding to and preventing sexual violence are becoming increasingly popular in the Australian policy context, but they are not without particular and unresolved challenges. As briefly discussed in this section, foremost among these is the nature and form of men's engagement in bystander prevention programs, as well as embedding bystander programs into organisations in sustainable ways. Finally, evaluating bystander approaches to sexual violence prevention remains significantly underdeveloped both in Australia and internationally.

Engaging men

As noted earlier, there are some critiques of the term bystander in the context of sexual violence prevention; since it implies individuals' externality and neutrality to sexual violence where arguably none exists. In short, we are all implicated in the structures of inequality, cultural norms and attitudes that are ultimately responsible for violence; and men, as the dominant group in societies where there is persistent gender inequality, are both collectively and individually implicated in the power structures, culture, and attitudes that underpin sexual violence against women. Critiques of implied neutrality hold particular relevance for one of the often expressed benefits of bystander approaches: namely that they provide a positive role for non-violent men in challenging sexual violence among their peers and communities, rather than only offering men an identity as "potential perpetrator".

Yet, how to effectively engage men in responding to and preventing sexual violence against women is itself contested (see Berkowitz, 2002; Pease, 2008). As Pease poignantly noted, if men's involvement in sexual violence prevention is limited to one of being a protector of female friends and family members, then such involvement potentially leaves problematic masculine identities and broader structures of gendered power relations and inequalities unchallenged (see also Connell, 2009). Arguably, men's genuine engagement in prevention of violence against women requires men to acknowledge and seek to change their own implication in perpetuating gender inequality (including violence), rather than allowing men to remain in the more comfortable turf as non-violent "allies" (Pease, 2008). Indeed, founder of the Mentors in Violence Prevention program, Jackson Katz, likewise warned of the "degendered discussions about bystander intervention" in which gender neutrality underpins program development and pedagogy, arguing instead for the importance of maintaining social justice approaches that emphasise the systemic gender inequalities that "are the context for, if not the root cause of, most interpersonal violence" (Katz, 2011, p. 689).

Engaging men as allies in sexual violence prevention is not unlike "ally" development in other social justice arenas (Casey & Smith, 2010). Allies are often understood as belonging to dominant social groups (such as men, whites, heterosexuals) who are "working to end the system of oppression that gives them greater privilege and power based on their social group membership" (Broido, 2000, p. 3). Moreover, taking a "stages of change" approach (see Box 5), such social justice allies may occupy different positions in terms of their readiness to change at different points in time (Berkowitz, 2002). Nonetheless, in other areas of social justice it is acknowledged that ally behaviour requires not only an awareness of social inequity (such as racism for example), but also "awareness of how one's own privilege may be complicit in the marginalisation of others" (Casey & Smith, 2010, p. 955). The extent to which much bystander programing seeks to facilitate such critical awareness of gendered power relations, and the effectiveness of doing so for individuals at different stages or readiness to change, remains unclear and is an area worthy of future research and evaluation efforts. Indeed, it may be that bystander programs themselves require gendered framing and differential content and approaches for male versus female target audiences, rather than a one-for-all approach.

Box 5: Stages of change

- Pre-contemplation: individuals are not aware of the problem, don't define an issue as a problem, and/or have to plans to act on the problem.

- Contemplative: individuals are aware of the problem, the costs/benefits of changing their behaviour and have some intention to take action.

- Preparation: individuals intend to take immediate action, or have plans to take action.

- Action: individuals have taken significant action to change their behaviour.

- Maintenance: individuals work to prevent relapse and are confident that they can continue to change their behaviour.

Source: Levesque, Prochaska, and Prochaska (1999)

Whole-of-organisational change

A further challenge in implementing bystander approaches lies in embedding change within organisations where programs are delivered, such that they are not confined to the individual level. In other words, where bystander approaches to sexual violence prevention are to be delivered in schools, workplaces and other organisational settings, successful implementation is facilitated by a whole-of-organisation approach (see Box 6). This means:

- ensuring commitment to sexual violence prevention at every level of the organisation (from the Principal/CEO, through upper, middle and lower management);

- multiple interventions (accompanying specific bystander programs with information, resources, and support/referral regarding sexual violence more generally); and

- ensuring that both formal policies and procedures (such as sexual harassment, sexual violence, discrimination and equity) as well as informal organisational culture (intolerant of sexism and tacit discrimination) take sexual violence seriously and support individuals taking action to prevent its occurrence in the organisation.

Furthermore, as identified by Murray and Powell (2007; 2008), there can be significant challenges in implementing and sustaining violence against women programs within organisations (such as workplaces) more generally. These include for example: ensuring safety and minimising risks to those directly affected by violence (who may be encouraged to disclose and seek support due to the prevention work taking place); promoting sustainability of programs (such that they continue beyond the good-will of a champion or ambassador within the organisation); and evaluation (discussed further below).

Box 6: Organisational approaches

Programs to promote bystander action in organisations must:

- increase knowledge of sexism, discrimination and violence against women - and awareness of the impacts of these behaviours and the costs of not taking action;

- increase skills to take bystander action safely and effectively;

- reduce the perceived social costs or increase the perceived benefits of taking bystander action; and

- promote organisational cultures that are conducive to pro-social bystander action through clear policies, procedures and leadership.

Source: VicHealth (2012)

Evaluating bystander programs

Evaluation of bystander approaches to responding to and preventing sexual violence is important to better ensure program effectiveness and sustainability. Nonetheless, evaluation is not always sufficiently built into the day-to-day management of many programs and community organisations. Many reasons contribute to the difficulty of incorporating evaluation, including the concern that evaluation may take time and resources away from strategy implementation (Cox, Craft, Keener, Wandersman, & Woodard, 2009) and tertiary responses. Designing and conducting empirical evaluative research, whether randomised control trials (RCT, see Tharp et al., 2011) or mixed method, longitudinal and qualitative approaches (see Campbell, 2011; Sullivan, 2011), require specific skill sets that may or may not be widely available in the community sector. There are also important ethical considerations when undertaking evaluative research involving randomised control trials that may exclude potential victim/survivors from access to support or programs as part of the evaluation design (see Powell & Imbesi, 2008). Additionally, there has been a history of limited funding and support made available to the community sector for evaluative work. Nonetheless, as many researchers and those working in prevention have noted, there is a clear need both for evaluation of programs focused on sexual violence and additional resourcing for that evaluation to occur.

Box 7: Organisational audit - "Take the Pulse"

- Identify and monitor gender equity indicators in your organisation (e.g., women's representation across management levels, women's involvement in high-profile organisational projects, pay equity).

- What policies, procedures, and formal reporting mechanisms are there to address sexual violence and harassment in the organisation?

- What informal culture and/or support among different levels of management is there for reporting incidents, and taking action as bystanders?

- What informal employee attitudes, norms, cultures and/or support is there for reporting incidents, and taking action as bystanders?

Adapted from InterAction (2010).

Planning for evaluation of bystander approaches to sexual violence prevention should occur early; alongside the planning and development of the program itself. Following the ecological model, evaluation should also take into consideration the context of program delivery. Conducting an organisational audit, or "taking the pulse" is one way to identify the structural and cultural factors in a program setting (whether it be a workplace, school, community group and so on) that may either facilitate or work against bystander programs and information campaigns (see Box 7; InterAction, 2010).

In addition to monitoring the organisational culture or environment in which bystander approaches are embedded, it is of course the main purpose of program evaluation to: support program development (formative evaluation); monitor program delivery (process evaluation); and finally, measure effectiveness (impact or summative evaluation) (see Wall (2013) for a discussion of evaluation of sexual violence prevention). Impact evaluations conducted with participants in bystander programs should seek to measure the following:4

- increased knowledge of the nature, extent, and seriousness of sexual violence to "notice the situation": could be measured by the Illinois Rape Myth Scale (see Payne et al., 1999) and/or items from the National Community Attitudes to Violence Against Women Survey (see VicHealth, 2009). This might also be accompanied by measures of increased knowledge of the nature, extent, and seriousness of related sexually aggressive behaviours, such as sexual harassment, sexually inappropriate jokes, and sexist discrimination against women;

- decreased denial or lack of awareness of sexual violence as a problem requiring intervention: can be measured using a 5-item scale developed by Banyard and Moynihan (2011); and

- increased intention and sense of responsibility to help: as measured by Bystander Intention to Help Scale (Banyard, 2008; Banyard & Moynihan, 2011).

It is an unfortunate problem that some evaluations of bystander programs end at this point (see Amar et al., 2012; Cissner, 2009); and as such have only measured changes in individuals' attitudes towards sexual violence, and their intention/sense of responsibility to take action in future. Key additional measures that should be routinely included in an evaluation of bystander approaches to sexual prevention are:

- increased confidence in skills and capacity: individual knows how to help/take action, and has confidence in their capacity to do help/take action effectively;

- increased confidence in peer support for bystander action: individual perceives that others in their peer group, community, organisation, workplace etc., take sexual violence seriously and support bystander action to prevent it; and

- long-term follow-up of reported action taken: in other words, did the individual notice a situation and take action 6, 12 or 24 months after completing the program? What was the action taken and what was the outcome?

As with other sexual violence prevention programs, a key gap in evaluation studies remains measures of reported action (and not just attitudinal change or behavioural intentions to act), and to follow-up with program participants in order to measure long-term change. These are the measures that are perhaps both the most difficult to implement, and the most crucial to ensure that first, programs have their intended effects (e.g., to guide future investment), and secondly, that programs do not have any unforeseen negative effects on participants (e.g., backlash).

Conclusion and further resources

While originally conceived to explain individual reluctance to help others' in an emergency, bystander approaches to preventing sexual violence are currently gaining momentum in public policy and program development in Australia. The importance of bystander approaches however, lies most in their potential to extend prevention beyond the individual and to community and cultural levels of change. As Katz (2011) noted, it is crucial that social justice framing/analyses of systems of inequality do not get "lost in translation" in bystander work - or this potential will be lost and the effectiveness of bystander approaches limited. While there are some unresolved challenges and issues in their implementation, bystander approaches represent a promising complementary approach to progressing sexual violence prevention.

Further resources for developing bystander approaches

Online campaigns and sample materials

- Know Your Power (University of New Hampshire) <www.know-your-power.org/>

- Hollaback - Campaign to end street harassment <www.ihollaback.org/>

Websites, resources and research reports

- Rape prevention through bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention (PDF 2.0 MB) (Banyard et al., 2005) <www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/208701.pdf>

- Bystander Intervention Wiki- PreventConnect <wiki.preventconnect.org/Bystander+Intervention>

- The Bystander Approach - Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs (WCSAP) <www.wcsap.org/bystander-approach-tip>

- Engaging bystanders in sexual violence prevention (PDF 933 KB) - National Sexual Violence Resource Center <www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Booklets_Engaging-Bystanders-in-Sexual-Violence-Prevention.pdf>

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1996). Women's Safety Survey, Australia (Cat. No. 4128.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2005 (Cat. No. 4906.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2012 (Cat. No. 4906.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70(9), 1-70.

- Amar, A. F., Sutherland, M., & Kesler, E. (2012). Evaluation of a bystander education program. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(12), 851-857.

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Banyard, V. L. (2011). Who will help prevent sexual violence? Creating an ecological model of bystander intervention. Psychology of Violence, 1(3), 216-229.

- Banyard, V. L., & Moynihan, M. M. (2011). Variation in bystander behavior related to sexual and intimate partner violence prevention. Psychology of Violence, 1(4), 287-301.

- Banyard, V. L., Eckstein, R. P., & Moynihan, M. M. (2010). Sexual violence prevention: The role of stages of change. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(1), 111-135.

- Banyard, V. L., Plante, E. G., & Moynihan, M. M. (2005). Rape prevention through bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention (PDF 2.0 MB) (Report to the US Department of Justice). Retrieved from <www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/208701.pdf>.

- Banyard, V. L., Plante, E. G., & Moynihan, M. M. (2004). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(1), 61-79.

- Berkowitz, A.D. (2002). Fostering men's responsibility for preventing sexual assault. In P. Schewe (Ed.), Preventing violence in relationships: Interventions across the life span (pp. 163-196). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Berkowitz, A.D. (2009). Response ability: Transforming values into action. Chicago, IL: Beck.

- Broido, E. M. (2000). The development of social justice allies during college: A phenomenological investigation. Journal of College Student Development, 41(1), 3-18.

- Burn, S. M. (2009). A situational model of sexual assault prevention through bystander intervention. Sex Roles, 60(11-12), 779-792.

- Carlson, M. (2008). I'd rather go along and be considered a man: Masculinity and bystander intervention. The Journal of Men's Studies, 16(1), 3-17.

- Carmody, M. (2009). Sex & ethics: Young people and ethical sex. Sydney: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carmody, M., Evans, S., Krogh, C., Flood, M., Heenan, M., & Ovenden, G. (2009). Framing best practice: National Standards for the primary prevention of sexual assault through education, National Sexual Assault Prevention Education Project for NASASV. Sydney: University of Western Sydney, Australia.

- Campbell, R. (2011). Guest editor's introduction. Part II: Methodological advances in analytic techniques for longitudinal designs and evaluations of community interventions. Violence Against Women, 17(3), 291-294.

- Casey, E., & Smith, T. (2010). "How can I not?": Men's pathways to involvement in anti-violence against women work. Violence Against Women,16(8), 953-973.

- Casey, E. A., & Lindhorst, T. P. (2009). Toward a multi-level, ecological approach to the primary prevention of sexual assault: Prevention in peer and community contexts. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 10(2),91-114.

- Casey, E. A., & Ohler, K. (2012). Being a positive bystander: Male antiviolence allies' experiences of "stepping up". Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(1), 62-83.

- Cissner, A. B. (2009). Evaluating the Mentors in Violence Prevention Program: Preventing gender violence on a college campus. New York: Center for Court Innovation.

- Clarke, D. (2003). Pro-social and anti-social behaviour. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Connell, R. (2009). Gender (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Cox, P. J., Craft, C. A., Keener, D., Wandersman, A., & Woodard, T. L. (2009). Evaluation for improvement: A seven-step empowerment evaluation approach for violence prevention organizations. Washington DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

- Darley, J. M. & Latane, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8,377-383.

- Dovidio, J. F., Pilavin, J. A., Schroeder, D. A., & Penner, L. A. (2006). The social psychology of prosocial behavior. E-book: Lawrence, Erlbaum.

- Dyson, S., & Flood M. (2008). Building cultures of respect and non-violence. Melbourne, Victoria: Australian Football League and VicHealth.

- Fabiano, P. M., Perkins, H. W., Berkowitz, A., Linkenbach, J., & Stark, C. (2003). Engaging men as social justice allies in ending violence against women: Evidence for a social norms approach. Journal of American College Health, 52(3), 105-112.

- French, J. R., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. Studies in Social Power, 150, 167.

- Heenan, M., & Murrary, S. (2006). Study of reported rapes in Victoria 2000-2003: Summary research report. Melbourne: Office of Women's Policy, Department for Victorian Communities.

- Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence against women an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4(3), 262-290.

- Imbesi, R. (2008). CASA House Sexual Assault Prevention Program for Secondary Schools (SAPPSS): Report. Melbourne: CASA House.

- Imbesi, R., & Lees, N. (2011). Boundaries, better friends and bystanders: Peer education and the prevention of sexual assault. A Report on the CASA House Peer Educator Pilot Project. Melbounre: CASA House:.

- InterAction. (2010). The gender audit handbook: A tool for organizational self assessment and transformation. Washington DC: InterAction.org.

- Katz, J., Heisterkamp, H. A., & Fleming, W. M. (2011). The social justice roots of the Mentors in Violence Prevention model and its application in a high school setting. Violence Against Women, 17,684-702.

- Levesque, D. A., Prochaska, J. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (1999). Stages of change and integrated service delivery. Consulting Psychology Journal, 51, 226-241.

- Levy, I., & Ben-David, S. (2008). Blaming victims and bystanders in the context of rape. In N. Ronel, K. Jaishankar, & M. Bensimon (eds.), Trends and issues in victimology (pp.175-191). Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- McCarry, M. (2007). Masculinity studies and male violence: Critique or collusion? Women's Studies International Forum, 30(5),404-415.

- McDonald, P., & Flood, M. G. (2012). Encourage. Support. Act! Bystander approaches to sexual harassment in the workplace. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- McMahon, S., & Banyard, V. L. (2012). When can I help? A conceptual framework for the prevention of sexual violence through bystander intervention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 13(1), 3-14.

- Men Can Stop Rape. (no date). The Where Do You Stand? Campaign. Retreived from <www.mencanstoprape.org/Strength-Media-Portfolio/preview-of-new-bystander-intervention-campaign.html>

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York: Harper & Row.

- Mouzos, J., & Makkai, T. (2004). Women's experiences of male violence: Findings from the Australian component of the International Violence Against Women Survey (IVAWS). Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Murray, S., & Powell, A. (2007). Family violence prevention using workplaces as sites of intervention. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management, 15(2), 62-74.

- Murray, S., & Powell, A. (2008). Working it out: Domestic violence issues and the workplace. Sydney: Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse, UNSW.

- Pease, B. (1995). Men against sexual assault. In W. Weeks, & J. Wilson (Eds), Issues facing Australian families (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Longman.

- Pease, B. (2008). Engaging men in men's violence prevention: Exploring the tensions, dilemmas and possibilities (Issues Paper No.17). Sydney: Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse.

- Potter, S. J. (2012). Using a multimedia social marketing campaign to increase active bystanders on the college campus. Journal of American College Health, 60(4),282-295.

- Potter, S. J., Moynihan, M. M., Stapleton, J. G., & Banyard, V. L. (2009). Empowering bystanders to prevent campus violence against women: A preliminary evaluation of a poster campaign. Violence Against Women, 15(1), 106-21.

- Powell, A., & Imbesi, R. (2008, February). Preventing sexual violence? Issues in program evaluation. Paper presented at the Australian Institute of Criminology Conference "Young people, crime and community safety: Engagement and early intervention", Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved from <www.aic.gov.au/events/aic%20upcoming%20events/2008/youngpeople.html>.

- Prevention Innovations, University of New Hampshire. (2011). Know Your Power®. Step in, speak up. As a bystander you can make a difference. Retrieved from <www.know-your-power.org/>.

- Rosenthal, A. M. (1964). Thirty-eight witnesses: The Kitty Genovese case. University of California Press.

- Schachter, S. (1951). Deviation, rejection, and communication. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46,190-207

- Schewe, P. A., & O'Donohue, W. (1993). Sexual abuse prevention with high-risk males: The roles of victim empathy and rape myths. Violence and Victims, 8(4), 339-351.

- Schwartz, M. D., DeKeseredy, W. S., Tait, D., & Alvi, S. (2001). Male peer support and a feminist routing activities theory: Understanding sexual assault on the college campus. Justice Quarterly, 18(3), 623-649.

- Schwartz, M. D., & DeKeseredy, W. (1997). Sexual assault on the college campus: The role of male peer support. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- Suedfeld, P. (2000). Reverberations of the Holocaust fifty years later: Psychology's contributions to understanding persecution and genocide. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 41(1), 1.

- Sullivan, C. M. (2011). Evaluating domestic violence support service programs: Waste of time, necessary evil, or opportunity for growth? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(4), 354-360.

- Sutton, A., Cherney, A., & White, R. (2013). Crime prevention: Principles, perspectives and practices (2nd ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Tharp, A. T., DeGue, S., Lang, K., Valle, L. A., Massetti, G., Holt, M., & Matjasko, J. (2011). Commentary on Foubert, Godin, & Tatum (2010) The Evolution of Sexual Violence Prevention and the Urgency for Effectiveness. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(16), 3383-3392.

- Ullman, S. E. (1997). Review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 24(2), 177-204.

- Ullman, S. E. (2007). A 10-year update of "Review and Critique of Empirical Studies of Rape Avoidance". Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(3), 411-429.

- VicHealth. (2012). More Than Ready: Bystander action to prevent violence against women. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation.

- VicHealth. (2009). National Community Attitudes towards Violence Against Women Survey 2009. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation.

- VicHealth. (2007). Preventing violence before it occurs: A framework and background paper to guide the primary prevention of violence against women in Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation.

- Wall, L. (2013). Issues in evaluation of complex social change programs for sexual assault prevention (ACSSA Issues No.14). Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault.

- Ward, K. J. (2001). Mentors in Violence Prevention program evaluation 1999-2000 (Unpublished report). Boston, MA: Northeastern University.

- World Health Organization. (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO.

- World Health Organization, & Butchart A. (2004). Preventing violence: A guide to implementing the recommendations of the World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: WHO.

Dr Anastasia Powell is lecturer in Justice & Legal Studies at RMIT University. Her research specialises in policy and prevention of violence against women. Most recently, Anastasia has worked with VicHealth and the Social Research Centre on the research report, More than Ready: Bystander Action to Prevent Violence Against Women.

Powell, A. (2014). Bystander approaches: Responding to and preventing men's sexual violence against women (ACSSA Issues No. 17). Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-922038-50-0