What is community development?

This resource sheet provides an introduction to community development for service providers and practitioners. This resource is for people working in the community services sector, so focuses on community development as a process facilitated by a community development worker. However, it should be noted that community development can be led by communities without the input of agencies.

Community development is a process where community members take collective action on issues that are important to them. This might be done with or without the support of a community development professional or agency. Community development is intended to empower community members and create stronger and more connected communities.

Community development is a holistic approach grounded in principles of empowerment, human rights, inclusion, social justice, self-determination and collective action (Kenny & Connors, 2017). Community development considers community members to be experts in their lives and communities, and values community knowledge and wisdom. Community development programs are led by community members at every stage – from deciding on issues to selecting and implementing actions, and evaluation. Community development has an explicit focus on the redistribution of power to address the causes of inequality and disadvantage.

Outcomes of community development

There are potential outcomes at both individual and community levels. Children and families directly involved in community development initiatives may benefit from an increase in skills, knowledge, empowerment and self-efficacy and experience enhanced social inclusion and community connectedness (Kenny & Connors, 2017). As community members are empowered and develop as leaders, they can begin to challenge and improve conditions that are resulting in their disempowerment or negatively impacting their wellbeing (Ife, 2016). At a community level, community development initiatives are likely to achieve long-term outcomes such as stronger and more cohesive communities, evidenced by changes in social capital, civic engagement, social cohesion, community safety and improved health (Haldane et al., 2019; Ife, 2016; Kenny & Connors, 2017).

What is not community development?

Community development is not one-off events, consultation to inform goals or strategies, community advisory groups or committees, or leadership training. All these things could be part of a community development strategy but, by themselves, they are not community development.

Community-based work and community development work

Community development can be undertaken independently by community members or groups, or with the support of a community development professional or agency. Community-based work that consults or involves community members is often confused with community development work. Table 1 outlines the difference between community-based work, which involves the community, and community development work, which is led by the community.

Table 1: Comparing community-based with community development work

| Community-based work | Community development work |

|---|---|

An issue or problem is defined by agencies and professionals who develop strategies to solve the problem and then involve community members in these strategies. Ongoing responsibility for the program may be handed over to community members and community groups. Characteristics:

Outcomes are pre-specified, often changes in specific behaviours or knowledge levels. | Community groups identify important concerns and issues, and plan and implement strategies to mitigate their concerns and solve their issues. Characteristics:

|

Source: Adapted from Labonte (1999)

When to use community development

Community development is not always a suitable approach to use. Community development may be particularly appropriate:

- to address social and community issues – community development is a good approach when you are trying to create change at a community or neighbourhood level. For example, if your goal is to improve community safety, increase community cohesion, reduce social isolation or create communities that are better for children.

- for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities – community development is a good approach to use with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander communities because it can enable self-determination and strengthen local First Nations organisations and grassroots community groups (Higgins [AIHW & AIFS], 2010)

- for disadvantaged communities – community development initiatives work well in disadvantaged communities where they can alleviate some of the impacts of disadvantage on children and families by building social capital and social inclusion (Ife, 2016; McDonald, 2011; Price-Robertson, 2011 [AIFS]; Ortiz et al., 2020) and can empower community members to challenge inequitable conditions that are negatively impacting their wellbeing (Ife, 2016).

Community development may not be the best approach if:

- You already know what you want to do – If the outcomes you want to achieve and the activities that you will use are already decided then there is no space for the community to determine outcomes and activities. Similarly, if you don’t have the authority or resources to implement the community’s decisions, community development is not a suitable strategy.

- You have limited time or short-term funding – Community development is a long-term process. Engagement and planning can take a year or more, and it can take several years to implement projects and ensure sustainable results.

- Your focus is improving specific individual skills – If you are seeking to build individual skills in a specific area (e.g. parenting skills or literacy), a program that targets these directly may be more appropriate.

Who can do community development?

It is important to recognise that community development is a practice with a well-developed theoretical framework. Community development practitioners should be familiar, through training or experience, with the theory, practice and principles of community development work. In saying this, it is important that community development practitioners have effective and respectful relationships with the communities they are working with, and sometimes the ability to build these relationships with the community is a more important quality for a worker than having a community development qualification. In these instances, it is important that the worker is supported by someone who has a good understanding of community development theory and practice.

What is the role of a community development practitioner?

The key role of a community development practitioner is to resource and empower the community (Kenny & Connors, 2017). This is done through a broad range of actions and activities, which change depending on the context. Community development practitioners support community members through the provision of information needed to identify issues and plan actions. This could include sharing information on local data, good practice around particular identified issues, and relevant programs and resources that are available. Community development practitioners also connect with and build local networks and leaders, undertake community engagement and plan, deliver and evaluate projects and programs. Community development practice has a focus on facilitation, education, capability building and resourcing skills.

Difference between community development and other approaches

Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD): ABCD is a version of community development that begins the development process by identifying and building on a community’s ‘assets’ rather than needs. Assets include physical spaces, skills, local knowledge, local groups and associations and networks as well as financial resources (Kretzmann & McKnight, 2005).

Strengths-based approach: A strengths-based approach seeks to build on an individual’s strengths rather than deficits. This can be a good practice for a community development practitioner to use but by itself is not community development.

Collective impact: Both community development and collective impact are place-based initiatives (i.e. they are developed in – and are unique to – the area in which they are delivered). Collective impact aims to create community-wide change on a particular social issue, and practitioners seek to do this by working towards five ‘conditions’ that provide a framework for collaboration between stakeholders (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

A key difference between collective impact and community development is the role that community members play in leadership and decision making. While initial descriptions of collective impact did not centre community as decision makers, collective impact is an evolving practice and more recent conceptualisations include a greater role for community engagement and leadership (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016). However, while some collective impact projects may be community-led, this is not universal. Community development is always driven by the community, with issues and actions determined by community members.

Key terms

Community: A community is often a geographical area; for example, a local government region or a particular town. Community can also be defined based on shared interests, identity or characteristics (e.g. a particular cultural and linguistically diverse community or the LGBTIQ community). Community in a community development sense refers to the citizens of the area, and does not usually refer to service providers or organisations.

Consultation: Consultation is the process of asking community members via surveys, interviews or focus groups for their opinion or preference on an issue. This is not participation in the community development sense.

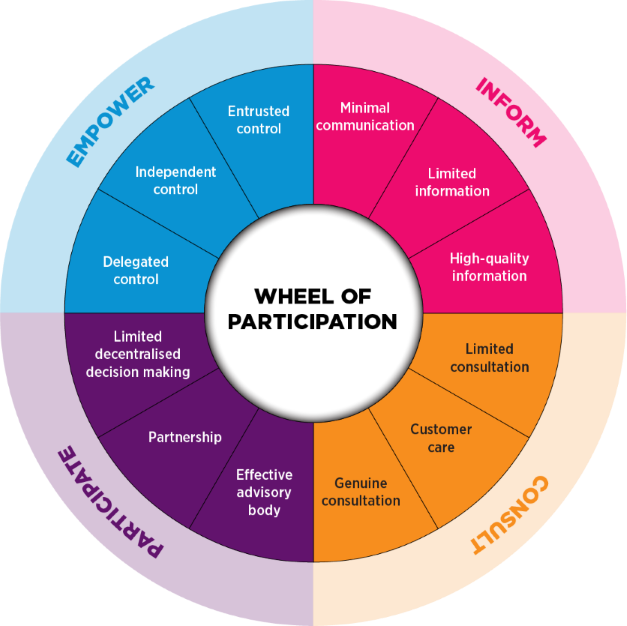

Participation: In community development, participation refers to the full involvement and leadership of community members in planning, developing, delivering and evaluating community actions or initiatives. Participation must not be tokenistic; community members must be participating in a way that is meaningful to them and to the community development project itself. It takes time to build full and meaningful participation. Figure 1 shows the different aspects of consultation, participation and empowerment.

Figure 1: The wheel of participation

Source: Dooris & Heritage (2013), adapted from Davidson (1998).

Further reading and resources

- Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Institute: Based at DePaul University in Illinois, the ABCD Institute has a range of resources and shares news updates about ABCD initiatives.

- Borderlands Institute of Community Development: Located in the suburbs of Melbourne, Borderlands aim to revitalise community development through education, publications and consultations.

- Collaboration for Impact: An Australian website and forum with information and resources on collective impact

- Collective Impact Forum: A US website and forum with information and resources on collective impact

- Ife, J. (2016). Community development in an uncertain world: Vision, analysis and practice (2nd ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Kenny, S. & Connors, P. (2017). Developing communities for the future (5th ed.). South Melbourne: Cengage Learning Australia.

- New Community Journal: An Australian quarterly journal for social justice, sustainability, community development and human rights

References

- Cabaj, M., & Weaver, L. (2016). Collective impact 3.0: An evolving framework for community change. Canada: Tamarack Institute.

- Dooris, M., & Heritage, Z. (2013). Healthy cities: Facilitating the active participation and empowerment of local people. Journal of Urban Health, 90(1), 74–91.

- Haldane, V., Chuah, F. L., Srivastava, A., Singh, S. R., Koh, G. C., Seng, C. K. et al. (2019). Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLOS One, 14(5), e0216112.

- Higgins, D. J. (2010). Community development approaches to safety and wellbeing of Indigenous children. Closing the Gap Clearinghouse. Canberra & Melbourne: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Ife, J. (2016). Community development in an uncertain world: Vision, analysis and practice (2nd ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011). Collective Impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter, 36–41.

- Kenny, S., & Connors, P. (2017). Developing Communities for the Future (5th ed.). South Melbourne: Cengage Learning Australia.

- Kretzmann, J. P., & McKnight, J. L. (2005) Discovering community power: A guide to mobilizing local assets and your organization's capacity. Illinois: ABCD Institute.

- Labonte, R. (1999). Community, community development and the forming of authentic partnerships: Some critical reflections. In M. Minkler (Ed.), Community Organising and Community Building for Health. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- McDonald, M. (2011). What role can child and family services play in enhancing opportunities for parents and families: Exploring the concepts of social exclusion and social inclusion. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Ortiz, K., Nash, J., Shea, L., Oetzel, J., Garoutte, J., Sanchez-Youngman, S. et al. (2020). Partnerships, processes, and outcomes: A health equity–focused scoping meta-review of community-engaged scholarship. Annual Review of Public Health, 41, 177–199.

- Price-Robertson, R. (2011). What is community disadvantage? Understanding the issues, overcoming the problem. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

This resource sheet was written by Jessica Smart, Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies. This paper was originally published in 2017. Minor edits and updates were undertaken by Jessica Smart in 2019 and 2023.