What is theory of change?

September 2021

Download Practice guide

Definition

Theory of change (Weiss, 1995) is an explicit process of thinking through and documenting how a program or intervention is supposed to work, why it will work, who it will benefit (and in what way) and the conditions required for success.

A theory of change is typically (but not always) developed in the design phase of program development and it is built on evidence, beliefs and assumptions (Jones & Rosenberg, 2018). Some theories of change draw from scientifically tested behaviour change theories because they can tell us a lot about how to positively influence people's behaviours.

Theory of change and program logic models

People often use the terms 'theory of change' and 'program logic model' interchangeably. However, there are important differences between the two concepts.

A theory of change is a diagram or written description of the strategies, actions, conditions and resources that facilitate change and achieve outcomes. It has 'explanatory power' (Reinholz & Andrews, 2020) in that it should explain why you think particular activities or actions will lead to particular outcomes.

A program logic model is a simpler (often linear) visual representation of how a program is supposed to work. It shows the actions and the particular outcomes expected from them. It can be based on the same information used in a theory of change; however, it doesn't explain how or why the program will achieve the desired outcomes or bring about change.

Sometimes a narrative theory of change is used to explain the theory or logic underlying a program logic model.

Reasons to develop a theory of change

A good theory of change can provide you with a program rationale that is based on the best available research and practice evidence while also clarifying any assumptions made about achieving success.

This can help in more effective program delivery and in assessing the merits of a particular program and its ability to achieve the outcomes you want to see. It can also help you to justify government or philanthropic spending and communicate your intentions to your community.

Another reason to develop a theory of change is because of its usefulness in evaluation (Church & Rogers, 2006). By explaining how you plan to get from program delivery to achieving outcomes, you will identify and begin to understand the set of conditions, activities and processes that contribute to change - and you can interrogate and test that knowledge through evaluation.

Finally, it can be an opportunity to engage with program staff and intended beneficiaries to:

- formalise tacit knowledge and experiences

- establish a shared vision of the program

- identify key enablers and barriers to success

(Aromatario et al., 2019; Funnell & Rogers, 2011).

In other words, theory of change can be used to make sure the people delivering or receiving a program or intervention are clear about why they are there and what they hope to achieve. It also allows for evidence collected by practitioners working directly with families, and families themselves, to guide key program decisions, processes and practices and improve the likelihood of the program achieving success.

Key theory of change elements

There is no standardised way of developing a theory of change; each one will have different features and details. However, the literature suggests that good theories of change address several key areas (see Chen, 2015; Funnell & Rogers, 2011; Reinholz & Andrews, 2020; W.K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004). These areas are described below.

Define the situation and desired results

Identify the problems or opportunities within your community that require a program response, the causes and consequences of those problems/opportunities, and the people most likely to be affected by them.

Describe what you hope to achieve in the long- term by addressing the situation.

Establish program boundaries

Scope the aspects of the situation you want to focus on and those you can focus on. What you can focus on will depend on several things including the resources you have, conditions attached to funding you receive and what other services are doing in the area.

Explore potential solutions

Research and explore possible ways to address the situation - those that are in and out of scope - and determine any necessary conditions for achieving outcomes (i.e. spaces, practices, people, timing, etc.) and anything that might stop or stall progress towards the impact you are seeking. You should also acknowledge any gaps in existing knowledge to signal areas that need further research.

Articulate assumptions

List the assumptions you have about why you think program decisions and strategies will work. Assumptions are ideas, beliefs, norms or principles that inform how you think about your program, the people involved, and how it will work.

For example, to realise your theory of change, you will probably assume that participants will turn up and complete the intervention. This is a necessary precondition for the intervention or program to work. Part of the process of doing a theory of change might be to see how realistic or uncertain these assumptions are.

Examples

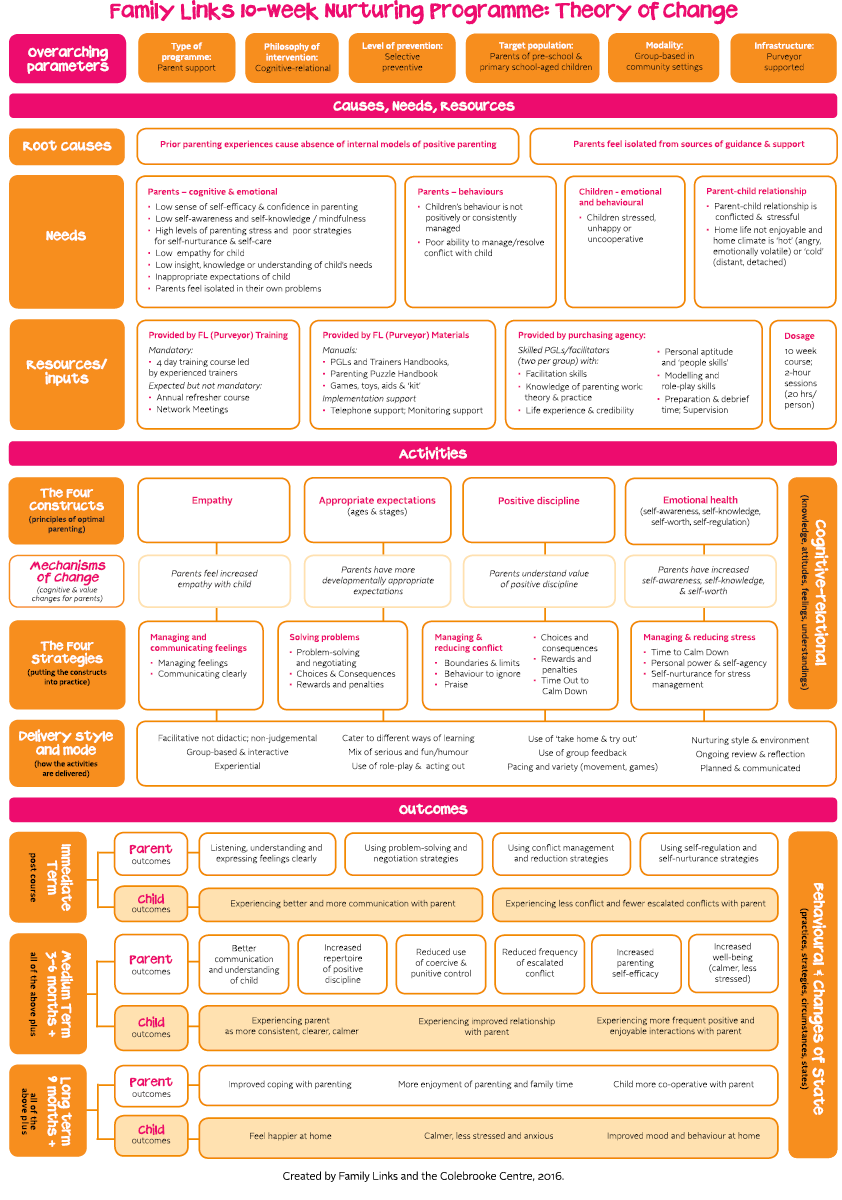

A theory of change is typically communicated in a narrative or diagram format (or both). Here is an example of a theory of change diagram.

Source: Ghate, D. (2018). Developing theories of change for social programmes: Co-producing evidence-supported quality improvement. Palgrave Communications, 4, 90.

For a narrative example, see Appendix 3 in the report Review of the use of ‘Theory of Change’ in international development published by the UK Department of International Development.

Additional resources

For guidance on how to develop a theory of change, see:

- Roadmap to social impact: your step-by-step guide to planning, measuring and communicating social impact (p. 16)

- Thinking big: How to use theory of change for systems change

- W.K. Kellogg Foundation Logic Model Development Guide (chapter 3)

- Patricia Rogers discussing theory of change for impact evaluation

- Better evaluation

For templates on creating a theory of change diagram, see:

References

- Aromatario, O., Van Hoye, A., Vuillemin, A., Foucaut, A., Prommier, J., & Cambon, L. (2019). Using theory of change to develop an intervention theory for designing and evaluating behavior change SDApps for healthy eating and physical exercise: The OCAPREV theory. BMC Public Health, 19(1435).

- Chen, H. T. (2015). Practical program evaluation: Theory-driven evaluation and the integrated evaluation perspective (2nd d.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Church, C., & Rogers, M. (2006). Designing for results: Integrating monitoring and evaluation in conflict transformation programs. Washington: Search for Common Ground.

- Funnell, S., & Rogers, P. (2011). Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Jones, N., & Rosenberg, B. (2018). Program theory of change. In SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation (pp. 1315-1318). SAGE Publications.

- Reinholz, D. L., & Andrews, T. C. (2020). Change theory and theory of change: What's the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education, 7(2).

- Weiss, C. H. (1995). Nothing as practical as good theory: Exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. In J. Connell, A. Kubisch, L. Schorr & C. Weiss (Eds.), New approaches to evaluating comprehensive community initiatives (pp. 65-92). New York: The Aspen Roundtable Institute.

- W. K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004). Logic model development guide. Michigan: W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

This resource was authored by Kathryn Goldsworthy, Senior Research Officer at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

This document has been produced as part of the Families and Children Expert Panel Project funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Social Services.

Revised November 2021.

Featured image: © GettyImages/PeopleImages