Participatory action research

Program evaluations assist organisations to plan, develop and improve their programs, with the aim of improving outcomes for clients (Alston & Bowles, 2003).

This snapshot of participatory action research is one of a series of CFCA resources on evaluation. For further information about other evaluation approaches and evaluation in general, see CFCA's research and evaluation resources.

What is participatory action research?

Participatory action research (PAR) is an approach to research rather than a research method (Pain, Whitman, Milledge, & Lune Rivers Trust, 2011). The approach seeks to situate power within the research process with those who are most affected by a program. The intention is that the participant is an equal partner with the researcher (Boyle, 2012; Patton, 2008).

The participatory nature of PAR refers to the active involvement of program clients, practitioners, and community members - plus any others who have a stake in the program, including funders, researchers and program managers.

A key element of this involvement is a process of collective, self-reflective inquiry, which stakeholders undertake in an effort to understand and improve upon practices in which they participate and situations in which they are engaged. This process is linked to action, which ideally leads to the people or communities that are affected having increased control over their lives (Baum, MacDougall, & Smith, 2006).

Terms and evaluation approaches that are closely related to PAR are outlined in Box 1.

Box 1: Terms closely related to PAR

- Participatory appraisal

- Rapid appraisal

- Participatory learning and action

- Community-based participatory research

- Co-operative/collaborative enquiry

- Participatory learning research

- Reciprocal research

- Critical action research

- Empowerment research

- Participant observation

- Emancipatory research

- Action learning

- Contextual action research

- Action science

- Soft-systems approaches

- Industrial action research

Source: Appel, Buckingham, Jodoin, & Roth, 2012; Bergold & Thomas, 2012; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2007; Land and Water Australia, 2009; Pain, Whitman, Milledge, & Lune Rivers Trust, 2011.

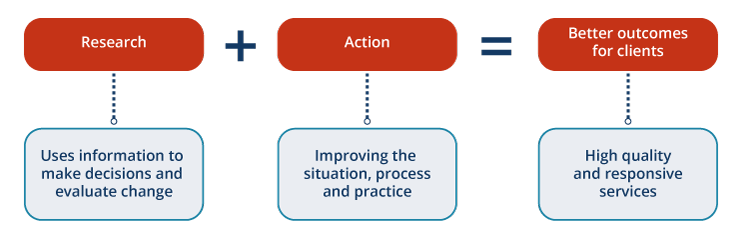

For program providers and evaluators, the PAR approach focuses on delivering high quality and responsive services. Figure 1 shows how action research emphasises the importance of using good information to make decisions that will improve practices and processes in order to deliver high quality, responsive services that lead to better outcomes for clients.

Figure 1: Research and action elements of PAR

Source: Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 2012, p.7.

The PAR approach

A distinct feature of participatory research models is the shift away from traditional research methods that are often characterised by an unequal relationship between researchers and participants (Baum et al., 2006).

PAR is a "principles-driven" approach to research (see Box 2). If followed, these principles offer a powerful way to deliver enhanced outcomes for clients and their communities. The principles of PAR can also guide researchers to choose research techniques and tools that suit the collective needs of clients, organisations, and other stakeholders.

Box 2: The principles of PAR

As a principles-driven approach, PAR is based around:

- social change - intended to enable action that leads to a change or improvement on an issue. This is achieved by converging science (research) with practice (change);

- participation - driven by research participants and other individuals or agencies who have a stake in the issue being researched (stakeholders);

- power of knowledge (empowerment) - a democratic model of communal learning, where knowledge is deliberately produced, owned and used by stakeholders, and provides new insights for both researchers and practitioners; and

- collaboration - expands the emphasis from action and change to collaborative research activities that occur at every stage of the research cycle, including program planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Source: Appel et al., 2012; Bergold & Thomas, 2012; Land and Water Australia, 2009; Pain et al., 2011.

PAR is used to help understand how individuals are connected to their social environments. This allows the approach to be applied at both the program delivery level and the community/societal level.

The difference between empowerment evaluations and PAR approaches is the extent to which the process is owned by participants. Fundamentally, the distinction rests with the degree to which the approaches shift the balance of power from researchers to the researched. That is, PAR seeks to primarily involve stakeholders, while empowerment evaluation aims to create a sense of ownership (Campbell et al., 2004; Secret, Jordan, & Ford, 1999).

Ownership, commitment and responsibility through participation

As partners in the PAR process, research participants are responsible for deciding what parts of the program are to be researched, how the data should be collected, and what to do with the results (Baum et al., 2006, 2006; Greene, 2006). The aim of this is an enhanced sense of responsibility that comes with active participation, which can provide greater opportunities to encourage self-determination and to strengthen client and/or community capacity (Baum et al., 2006; Owen, 2006; Schwandt & Burgon, 2006).

By participating in all stages of the research process, both participants and program workers are more likely to feel ownership of, and commitment to the program (Patton, 2008. The active involvement of program practitioners and workers in the PAR approach can also lead to longer term, more sustainable improvements in program delivery (Mulroy & Lauber, 2004; Patton, 2008). This can help to create an organisational culture of research and evaluation.

When should PAR be used?

PAR is primarily designed for those who are considered vulnerable or experience a lack of control over their lives (Alston & Bowles, 2003; Fitzpatrick, Sanders, & Worthen, 2011). PAR has been adopted across a wide range of contexts, including health, education, early intervention, and community strengthening sectors (Baum et al., 2006; DHHS, 2012), where longer term change has been needed to deliver more sustainable outcomes for vulnerable client groups and communities (Boyle, 2012; see also The Knowledge & Adoption Toolkit, Land and Water Australia, 2009).

PAR is considered particularly relevant for Indigenous communities, where the approach can help to reduce "colonising effects" (such as exploitation, disrespect, powerlessness, and misrepresentation) on Indigenous societies and culture (Baum et al., 2006). PAR's ability to strengthen the capacity of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) groups has also been noted (Alston & Bowles, 2003).

In addition to the prospect of delivering long-term outcomes, there is a range of benefits to the PAR approach. The limitations of the approach also need to be considered when planning for a program evaluation. Table 1 provides a snapshot of the benefits, limitations, and the contexts in which PAR should, or should not, be used.

| Benefits of PAR | Limitations of PAR |

|---|---|

|

|

| When to use PAR | When NOT to use PAR |

|

|

Source: Adapted from The Knowledge & Adoption Toolkit, Land and Water Australia, 2009; Greene, 2006.

The PAR process

Resources are available to help program planners and agencies through the PAR process (see further information below). The methods adopted will be heavily informed by the research participants themselves, who will decide what elements of the program are to be researched, how data should be collected and what to do with the results (Baum et al., 2006; Greene, 2006). This typically requires a collaborative effort to identify problems, collect evidence and draw conclusions about how best to improve service delivery (Alston & Bowles, 2003; Owen, 2006).

The role of the evaluator

The role of the evaluator is to help guide participants through the PAR process and to ensure participants are ready to take part in every stage of the evaluation (Schwandt & Burgon, 2006).

There is likely to be a range of differing views and priorities within and across participating groups. This is where evaluators can work closely with participants to help find a balance between competing priorities and promote the benefits of the evaluation, to ensure "buy-in" from the participants and to create the necessary conditions required for the PAR approach (see Box 3).

Box 3: Establishing the conditions for PAR

Prior to undertaking the PAR approach, the research participants should:

- recognise the value of local knowledge;

- accept and own research results;

- be willing to be involved in all stages of the research;

- be willing to include a wide range of participants; and

- choose research methods that suit the situation, and that communities or groups can learn to use without outside help.

Source: The Knowledge & Adoption Toolkit, Land and Water Australia, 2009.

How is PAR done?

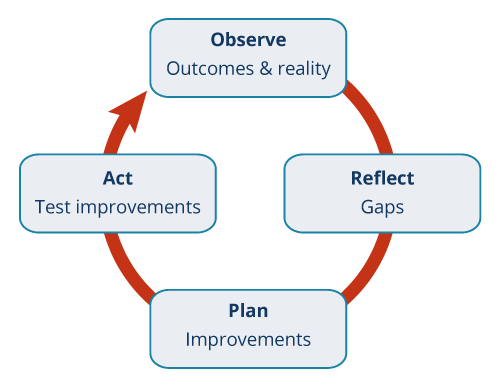

The PAR cycle commonly revolves around four simple steps: plan, act, observe, and reflect (DHHS, 2012; Kindon, Pain, & Kesby, 2007). Figure 2 shows how these steps form a continuous quality improvement process.

Figure 2: PAR research cycle

Source: DHHS, 2012, p.8.

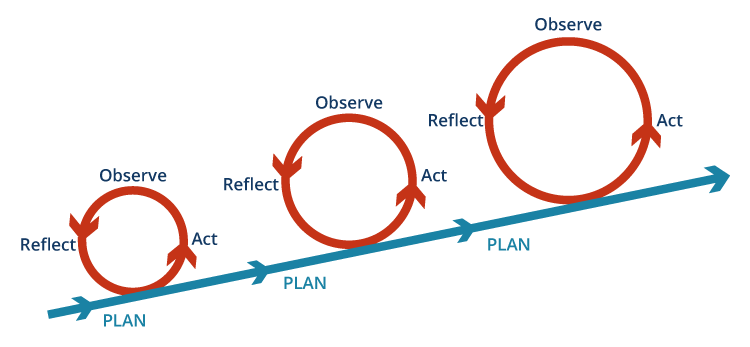

Figure 3 shows how these cycles are repeated to allow for incremental changes to a program over time. The increasing size of the cycles reflects an increase in focus, power, and impact and the questions driving them; each cycle allows more stakeholders to be drawn into the process (DHHS, 2012).

Figure 3: Building upon PAR research cycle

Source: Crane & Richardson, 2000, as cited by DHHS, 2012, p.10.

While this explains the process, there is no one particular research method of conducting PAR. Many different methods can be used, and what is appropriate depends on the evaluation context and on the needs of clients, the broader community, and the specific conditions in which programs are delivered (Kindon et al., 2007). Decisions related to which research tools to use (e.g., surveys, interviews, focus groups) are made in consultation with participants (Kindon et al., 2007).

Further information about the PAR process

Further information, suggestions, and PAR toolkits are available from the following websites:

- Research for Organizing: A toolkit for Participatory Action Research from the Community Development Project

- Incite provides links to toolkits

- The Knowledge & Adoption Toolkit

- The Action Research and Learning Toolkit (PDF 951 KB)

References

- Alston, M., & Bowles, W. (2003). Research for social workers (2nd ed.). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

- Appel, K., Buckingham, E., Jodoin, K., & Roth D. (2012). Participatory learning and action toolkit: For application in BSR's global programs. Retrieved from <herproject.org/downloads/curriculum-resources/herproject-pla-toolkit.pdf>

- Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60,854-857.

- Bergold, J., & Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1).

- Boyle, M. (2012). Research in action: A guide to Participatory Action Research (Research Report). Canberra: Department of Social Services. Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/06_2012/research_in_action.pdf>

- Campell, R., Dorey, H., Naegeli, M., Grubstein, L. K., Bennett, K. K., Bonter, F., Smith, P. K. et al. (2004). An empowerment evaluation model for sexual assault programs: Empirical evidence of effectiveness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(3/4), 251-262.

- Crane, P., & Richardson, L. (2000). Reconnect action research kit. Canberra: Department of Family and Community Services.

- Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). The action research and learning toolkit. Hobart: Department of Health and Human Services Tasmania.

- Fitzpatrick, J. L., Sanders, J. R., & Worthen, B. R. (2011). Program evaluation: Alternative approaches and practical guidelines (4th ed.). New Jersey, US: Pearson Education.

- Greene, J. C. (2006). Evaluation, democracy and social change, In I. F. Shaw, J. C. Greene, & M. M. Mark,(Eds), The SAGE handbook of evaluation(Chapter 5).London: SAGE.

- Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2007). Participatory action research: Communicative action and the public sphere. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Kindon, S., Pain, R., & Kesby, M. (Eds). (2007) Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place. London: Routledge

- Land and Water Australia. (2009). The knowledge & adoption toolkit. Retrieved from <katoolkit.lwa.gov.au/node/29>

- Mulroy, E. A., & Lauber, H. (2004). A user friendly approach to program evaluation and effective community interventions for families at risk of homelessness. Social Work, 49(4), 573-586.

- Owen, J. M. (2006). Program evaluation: Forms and approaches (3rd ed.).Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

- Pain, R., Whitman, G., Milledge, D., & Lune Rivers Trust. (2011). Participatory action research toolkit: An introduction to using PAR as an approach to learning, research and action. Durham: Durham University.

- Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-focused evaluation (4th ed.). London: SAGE.

- Schwandt, T. A., & Burgon, H. (2006). Evaluation and the study of lived experience,InI. F. Shaw, J. C. Greene, & M. M. Mark,(Eds), The SAGE handbook of evaluation (Chapter 4).London: SAGE.

- Secret, M., Jordan, A., & Ford, J. (1999). Empowerment evaluation as a social work strategy. Health and Social Work, 24(2), 120-127.

This paper was developed and written by Kate Rosier, consultant, with Shaun Lohoar, Sharnee Moore and Elly Robinson, CFCA information exchange.

The feature image is by Impact Hub, CC BY-SA 2.0.