Families make all the difference

Helping kids to grow and learn

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

May 2012

Download Research report

Overview

Using reports from parents and children in Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), this fact sheet looks at how families are supporting children’s physical, learning and social emotional development.

This Facts Sheet has been prepared for the 2012 National Families Week, with this year's theme being "Families make all the difference: Helping kids to grow and learn". It provides a range of information on ways in which families nurture and support children's physical, learning and social emotional development.

The focus of this Facts Sheet is on families with children aged up to around 11 years old. We present analyses and data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC)1 to explore what children and their parents have to say about topics related to the growth and development of children in the family context. While families are also important in raising children older than 11 years, there are specific issues facing younger children that are important for setting them on a healthy and happy path in life.

Helping children to grow and learn occurs within families in very many ways, from providing a safe and nurturing home environment, through being involved in children's learning activities at school, home and elsewhere, and giving children the input and direction they need to grow up with the social and emotional capabilities to tackle everyday life. We will explore this here by looking at children's physical, learning and social-emotional development.2

While devoting resources to raising children is no doubt a priority of parents with young children, they often have to find ways of fitting both paid work and parenting into their lives. The 2012 International Day of Families (on 15 May) focuses on the theme of "Ensuring work family balance". In recognition of this, we also provide some information on the interaction between work and family, considering both the positive and negative ways in which work can flow through to family life.

Growing Up in Australia

LSAC focuses on two age cohorts of children and their families, with each cohort comprising approximately 5,000 children. The first survey wave was conducted in 2004, when children in the younger cohort were infants (called the "B cohort") and those in the older cohort were 4-5 years old (called the "K cohort"). These two cohorts and their families are followed up every two years, with the most recent data available for analysis having been collected in 2010 (Wave 4), when the B cohort children were aged 6-7 years and the K cohort children were aged 10-11 years.

Helping kids grow up healthy

Helping children grow is fundamental to parenthood. Children need to be given nutrition, sleep and exercise to ensure their healthy growth from infancy onwards.

For infants, breastfeeding is recognised as providing a healthy start to life. In the LSAC sample, 92% of infants were breastfed from birth, 82% were still being breastfed at one month old and 70% were still breastfed at three months old.3

As children grow, parents and carers introduce them to other foods. A healthy diet is one that includes fruit and vegetables. According to LSAC, in the 24 hours prior to interview:4

- 92% of 4-5 year old children had at least one serve of fresh fruit and 48% had at least two serves of vegetables (cooked or raw);

- 90% of 6-7 year old children had at least one serve of fresh fruit and 50% had at least two serves of vegetables (cooked or raw); and

- 87% of 8-9 year old children had at least one serve of fresh fruit and 47% had at least two serves of vegetables (cooked or raw).

Having a healthy diet encompasses more than this, and should take account of the amount and range of food and drink in children's diets.

Focusing on 10-11 year old children, most primary carers5 appeared unworried about their child's diet. When asked about this:

- 61% of parents were not concerned about their child eating too much or eating unhealthy foods, 29% said they were a little concerned, and 10% said they were concerned; and

- 86% of parents were not concerned about their child eating too little, 9% were a little concerned, and 5% were concerned.

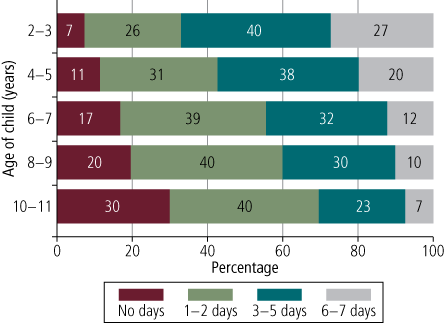

Having appropriate levels of exercise is important to children's physical development. Parents may help to encourage their children to participate in active play by engaging in more active pastimes with their children. As seen in Figure 1, this happens more frequently when children are young (2-3 years old) compared to when they are of primary school age (10-11 years). No doubt this in part reflects differences in the nature of children's days as children grow older, with school time and outside-school sports substituting for parental time in these activities.

Figure 1: How often adults in the family played outdoor games with their children

Note: The question asked: "In the past week, on how many days have you or an adult in your family played a game outdoors or exercised with the child, like walking, swimming or cycling?"

Source: All cohorts/waves except B cohort Wave 1

With children often engaged in activities like watching television, using the computer and playing electronic games, parents may be concerned about the inactivity of children. For example, among the primary carers of children aged 10-11 years:

- 46% were not concerned about the child spending too much time in front of the TV, computers or doing other sedentary things;

- 36% were a little concerned; and

- 18% were concerned.

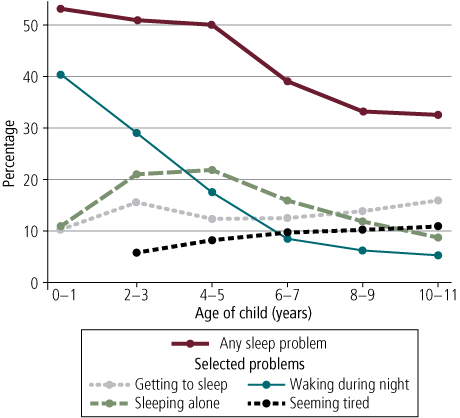

Sleep is also important. Children may have a range of difficulties with sleeping that can be challenging for parents to manage. The nature of these difficulties is likely to change as children grow, as seen in Figure 2, which shows the overall percentage of children who had sleep problems, and the most prevalent types of problems reported.6 For example:

- at age 0-1 years, 53% of children were reported to have a sleep problem, with the most common problem being waking during the night (40% of 0-1 year olds);

- at ages 2-3 and 4-5 years, just over 50% of children had a sleep problem, with the problem of waking during the night declining from 29% of 2-3 year olds to 17% of 4-5 year olds, and children of these ages being more likely than children of other ages to have problems sleeping alone; and

- the incidence of sleep problems declined for older children, compared to those of younger ages, with the older children experiencing a mix of sleep problems, including getting to sleep, sleeping alone and seeming tired.

Figure 2: Children having sleep problems and the types of problems they had

Source: All cohorts/waves

An emerging challenge as children grow, is helping them with the physical changes that accompany the transition to adolescence. The oldest of the LSAC children were aged 11 years at their most recent interview, and so many were just beginning these changes.7 For primary carers of children aged 10-11 years:

- 87% said they were not concerned about their child's physical changes related to puberty;

- 9% said they were a little concerned; and

- 4% said they were concerned.

Helping kids learn

In this section, we focus on ways in which families provide opportunities for children to develop learning or cognitive skills. We include information about parents reading to children and helping them with homework. We also explore some aspects of parental engagement with schools.8

First, we present parents' reports of whether they thought they were equipped to help with specific elements of children's learning activities. Parents of 6-7 and 10-11 year old children were asked how they felt about their ability to help their child in different aspects of school success, specifically about whether they agreed or disagreed that they knew how to help their child to do well in school and help them with difficult homework. Figure 3 shows that:

- the majority of mothers and fathers either agreed or strongly agreed that they were able to help their child do well in school or help with difficult homework;

- mothers were somewhat more likely than fathers to strongly agree, rather than agree, in these matters; and

- parents (especially mothers) of 6-7 year olds were more likely than parents of 10-11 year olds to strongly agree that they were able to help children with school and homework.

Figure 3: Whether mothers and fathers thought they could help children with school and difficult homework

Source: B and K cohorts, Wave 4

Parental input to child learning can begin at a very young age; for example, through parents talking and reading to children. Then, children's developmental needs for learning will vary considerably as they grow and become more independent in the way they acquire new knowledge and skills.

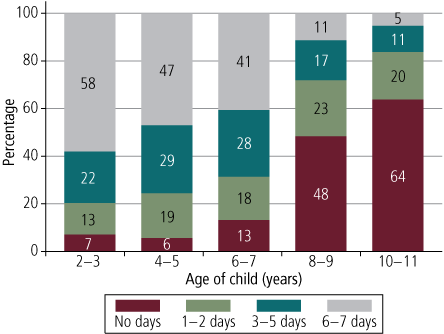

We can see in Figure 4 that:

- 58% of 2-3 year olds were read to on 6-7 days in the past week, with another 22% read to on 3-5 days in the past week; but

- by age 8-9 years, parents are much less likely to be frequently reading to or with their child, with 11% doing so on 6-7 days in the past week and another 17% on 3-5 days.

Figure 4: How often adults in the family read to or with the child

Note: At Waves 1-3, the question asked: "In the past week, on how many days have you or an adult in your family read to the child from a book?". At Wave 4, the question referred to reading with the child from a book.

Source: All cohorts/waves except B cohort Wave 1

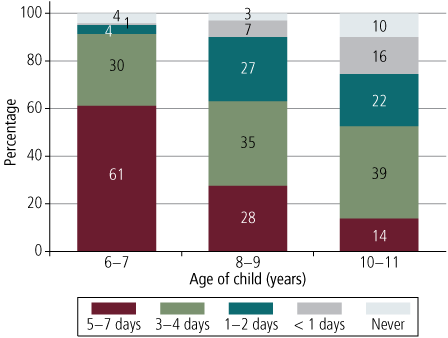

Parental involvement with children's homework also declines as children grow older (Figure 5), which reflects the increasing ability (and need) for children to learn on their own. In particular, as homework for the youngest children often entails reading to parents, this decline will be evident as children read more on their own.

Figure 5: How often parents helped their children with homework

Note: Response categories for the 6-7 year olds were different from those used in the graph. For simplicity of presentation, "daily" has been included in the category "5-7 days"; "a few times a week" in "3-4 days", "once a week" in "1-2 days", "a few times a month" in "< 1 day", and "less often" in "never".

Source: K cohort Wave 3, B cohort and K cohort Wave 4.

Figure 5 shows that:

- 61% of parents helped their 6-7 year olds with homework most days;

- 28% of parents helped their 8-9 year olds most days; and

- 14% of parents helped their 10-11 year olds most days.

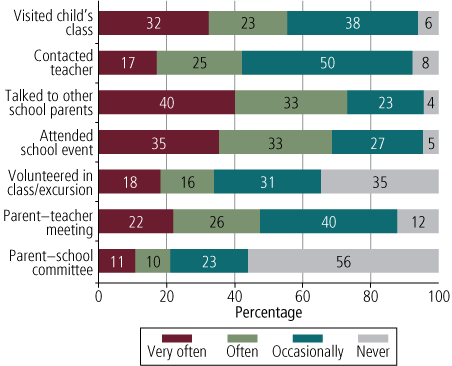

The main way in which primary-school-aged children's learning develops is through their attendance at school. Parental engagement in school can be an important indicator of how confident parents feel about supporting their child's learning. Figure 6 shows some indicators of school engagement by primary carers when children were aged 6-7 years (in the early to middle years of primary school):

- Parents were most often engaged through talking to other school parents, attending school events and visiting their child's class.

- The next most frequent means of engaging with the school were parent-teacher meetings and contacting the teacher.

- Less frequent engagement occurred through participation in parent-school committees and volunteering in the class or excursions.

Figure 6: How often primary carers of 6-7 year olds engaged with the school

Source: B cohort Wave 4

Of course, "learning" is more than just achieving at school. Parents also teach children about culture, religion and the world around them. This, for example, might be done by visiting museums, attending concerts, or participating in religious instruction or activities. Among children aged 10-11 years, for example, 44% had been taken by either parent to a concert, play, museum, art gallery or community or school event in the previous month. Also, 30% of children at this age had attended a religious service, church, temple, synagogue or mosque with either parent in the previous month.9

Helping kids grow socially and emotionally

Another very important aspect of children's growth is that of how they develop socially and emotionally. The social-emotional wellbeing of children tends to be strongly associated with the characteristics of parents and families,10 and so the family is an important context for taking care of these developmental needs of children. In particular, parents have an important role in being there for their children, and providing support and guidance when children face difficulties that they cannot face alone. This becomes especially important as children grow and face challenges not only inside, but also outside the family, as happens more as children enter and continue through school.

Helping children to grow socially and emotionally is likely to rely upon parents spending time with children, and developing and sharing positive and happy relationships with them. To examine this, we have included a range of responses from both children and parents that provide some indication of the quality of the time spent and their relationships with each other.

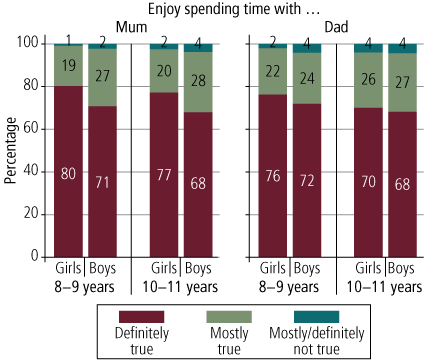

From the child's perspective, one indication of there being quality family time is whether children say that they enjoy spending time with their mother and with their father. When children were asked about this (when aged 8-9 years, and two years later at 10-11 years), the vast majority of children were very positive in their responses (Figure 7):

- Girls tended to be a little more positive than boys overall, with a higher percentage saying it was definitely true that they liked spending time with their mother (80% at age 8-9 years and 77% at 10-11 years). For boys, 71% at age 8-9 years and 68% at age 10-11 years said it was definitely true that they liked spending time with their mother.

- Similarly, of children aged 8-9 years, a slightly higher percentage of girls than boys said that it was definitely true that they liked spending time with their father. However, at age 10-11 years, this difference between boys and girls was not apparent.

- Most other children said it was mostly true that they liked spending time with each parent. Only a very small minority of children reported that they did not enjoy spending time with their mother or their father.

Figure 7: Whether children enjoyed spending time with their mothers and fathers

Source: K cohort Waves 3 and 4

As reported later on in the work-family balance section of this Facts Sheet, parents' time with children often has to be fit around work time and so parents may feel they do not have enough time with their children.

When primary carers of 10-11 year olds were asked whether they had any concerns about how much time they spent with their child:

- 60% said they had no such concerns;

- 25% said they had concerns "a little"; and

- 15% said they had concerns.

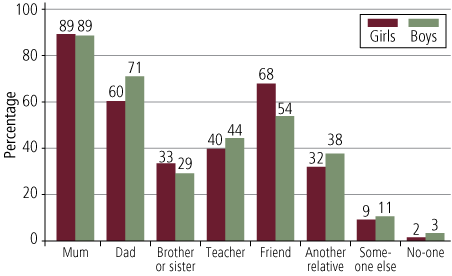

Spending time together is valuable as it provides opportunities for parents and children to develop relationships with each other and, in particular, for parents to help children with any issues or difficulties they may be confronting. Children may also see their parents as being an important source of advice and support. Mothers were most often consulted when 10-11 year old children had problems (Figure 8). For boys, fathers were the next most common source of help when they had problems, followed by friends. Girls were somewhat more likely to go to friends next, followed by their fathers.

Figure 8: Who 10-11 year old girls and boys consulted if they had problems

Source: K cohort Wave 4

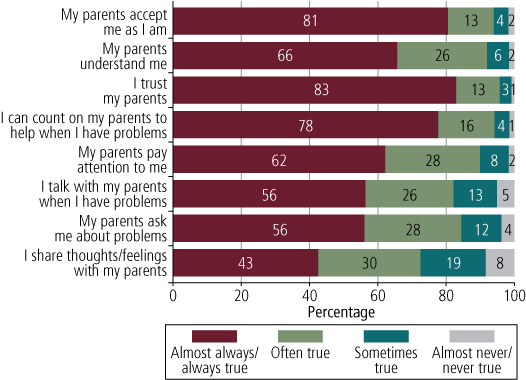

More detailed information about how 10-11 year old children perceived their relationship with their parents is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: How 10-11 year olds perceived their relationship with their parents

Source: K cohort Wave 4

The data in Figure 9 show that the majority of children reported positively on all aspects of these relationships:

- The highest levels of agreement were in matters of trust and acceptance, with more than 80% of children saying it was almost always or always true that their parents accepted them as they were and that they trusted their parents.

- The lowest levels of agreement were in relation to sharing thoughts and feelings with their parents (43% said it was almost always or always true that they did this), and talking to parents or having parents ask them about problems (56% said it was almost always or always true that this occurred).

Work and family

While raising children is likely to be a central concern of parents, their parenting time often competes with time spent in paid employment. Finding a way of meeting the demands of paid work as well as taking care of children is difficult for many parents.

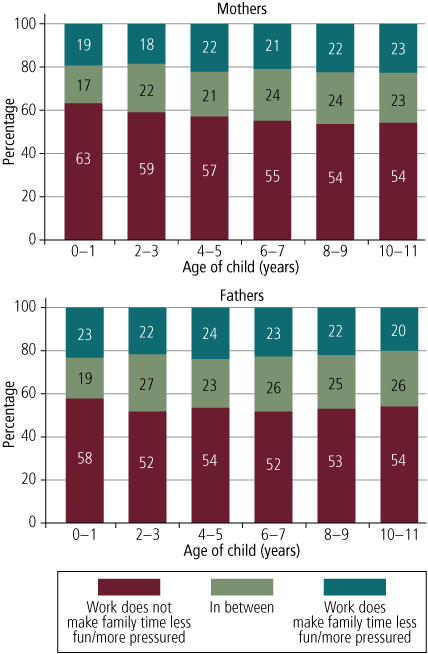

As such, there can be negative aspects of work, perhaps because of the time constraints on family that come about because of work hours, or because of a "spillover" of work-related worry or stress into family time. For example, among employed parents of children aged 10-11 years:

- 23% of mothers said (agreed or strongly agreed) that work makes family time less enjoyable and more pressured, 23% neither agreed nor disagreed, and 54% disagreed or strongly disagreed; and

- 20% of fathers said that work made family time less enjoyable and more pressured, 26% neither agreed nor disagreed, and 54% disagreed or strongly disagreed.

Figure 10 shows that for mothers and fathers, there was some variation across ages of children in reports of work making family time less enjoyable and more pressured. Both mothers and fathers, if employed, were more likely to report that work made family time less enjoyable and more pressured when children are younger. The differences, however, were not very great, such that even among employed mothers and fathers of children aged 0-1 years, around six in ten parents said that work did not make family time less enjoyable and more pressured.

Figure 10: Employed mothers and fathers reporting on whether work made family time less enjoyable and more pressured

Source: All cohorts/waves

Children can be aware of or affected by the spillover of parents' work into family time. This may result in some children feeling that parents spend too much time working. For example, for 10-11 year olds with a mother or father in paid work:

- 35% said their father worked too much, 63% said he worked about the right amount and 2% said he worked too little; and

- 27% said their mother worked too much, 71% said their mother worked about the right amount and 2% said she worked too little.

If we compare these responses to the parents' responses on whether work made family time less fun, some connection was apparent. For example:

- When mothers said work made family time less fun, 34% of children also said their mother worked too much. This compares to 22% for children whose mothers said that work did not make family time less fun. (For mothers who were in between these extremes, 29% of children said their mother worked too much.)

- When fathers said work made family time less fun, 43% of children also said their father worked too much. This compares to 29% for children whose fathers said that work did not make family time less fun. (For fathers who were in between these extremes, 36% of children said their father worked too much.)

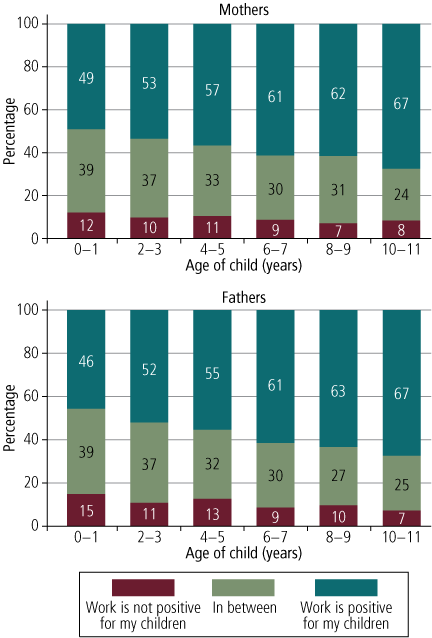

It is important to recognise, though, that parents do not always see paid work in a negative light. In addition to the financial rewards, paid employment can have a range of benefits for parents, including experiencing social interaction and feelings of satisfaction for doing interesting and/or meaningful work. It also provides an opportunity for good role modelling. These positive aspects of employment can flow through to children. For example, among employed parents of children aged 10-11 years:

- 67% of mothers said (agreed or strongly agreed) that work had a positive effect on their children, 24% neither agreed nor disagreed, and 8% disagreed or strongly disagreed;

- 67% of fathers said that work had a positive effect on their children, 25% neither agreed nor disagreed, and 7% disagreed or strongly disagreed.

In Figure 11, we can see that as children grow older, parents are increasingly likely to say that work has a positive effect on their children.

Figure 11: Employed mothers and fathers reporting on whether their work had a positive effect on their children

Source: All cohorts/waves

"Work", of course, also occurs in the home. Children can participate in this housework, and this is likely to help their development in learning to take responsibility for particular tasks. Of the 10-11 year olds in LSAC:

- 53% often helped around the house;

- 36% sometimes helped around the house; and

- 11% seldom or never helped around the house.

Final comments

In this Facts Sheet, we have focused on families and their place in helping children grow and learn. We have provided some information on the various ways in which parents and families contribute to children's development, for children of different ages, up until the ages of 10 or 11 years old. Clearly, families matter also to older children, and as LSAC progresses and the children in the study grow older, we will be able to investigate these issues through the adolescent years.

Although we have focused here on families, it is important to recognise that family members do not undertake these roles in isolation. Various resources are also available to parents who may be seeking guidance on particular aspects of raising children.11 There are also supports available in schools, communities and neighbourhoods and within extended families that can and do make valuable contributions to the positive development of Australian children.

Endnotes

1 LSAC is conducted in a partnership between the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). The findings are those of the authors and should not be attributed to FaHCSIA, AIFS or the ABS.

2 We know that families are diverse in nature; for example, they include step-families and those headed by single parents and same-sex parents. Some children spend time living in more than one household. Differences in family forms, along with cultural and geographic diversity, may all contribute to there being differences across families in how they raise their children. While we are aware of these matters, such complex issues cannot be examined here.

3 Based on calculations from the B cohort. See the LSAC 2006-07 Annual Report <www.aifs.gov.au/growingup/pubs/ar/ar200607> for more details.

4 These analyses use data from the B cohort Waves 3 and 4, and the K cohort Wave 3.

5 The "primary carer" in a family is the parent who has been nominated as the one who knows most about the LSAC study child. In the vast majority of families this is the mother.

6 The LSAC 2009-10 Annual Report <www.fahcsia.gov.au/our-responsibilities/families-and-children/publications-articles/the-longitudinal-study-of-australian-children-2009-10-annual-report> provides more detailed analyses of the amount of time children spend sleeping, and the times children go to bed and wake up.

7 See the LSAC 2009-10 Annual Report for more analyses of children and puberty.

8 See Suzanne MacLaren's article on the family education environment, in the LSAC 2010 Annual Statistical Report <www.aifs.gov.au/growingup/pubs/asr/2010>, for more analyses on this topic.

9 More comprehensive insights into children's learning environments can be gained by looking at how children spend their time, especially in relation to time spent in activities that might enhance learning development (such as reading and homework), as opposed to those that might not be so positive (potentially, watching television). See, for example, Bittman and Sipthorp's article on children's patterns of television viewing, in the LSAC 2011 Annual Statistical Report.

10 See, for example, Smart, D., Sanson, A., Baxter, J. A., Edwards, B., & Hayes, A. (2008). Home-to-school transitions for financially disadvantaged children (PDF 639 KB). Sydney: The Smith Family. Retrieved from <www.thesmithfamily.com.au/~/media/Files/Research%20and%20Advocacy%20PDFs/Research%20and%20Evaluation%20archive%20PDFs/home-school-summary-2008.ashx>.

11 For example, the Raising Children Network website <raisingchildren.net.au> provides useful references for parents seeking information on how to tackle identified issues and concerns.

Key messages

-

Around nine out of 10 children aged 4–9 were eating at least one serve of fresh fruit a day, but only 50% were eating two serves of vegetables.

-

Parents participation in children’s active play decreased as children get older, and over half of parents with children aged 10–11 had some concerns about their child spending too much time doing sedentary things.

-

Parents most commonly read to children regularly when they were 2–3 years, and most often help with homework when children were in their early years at school (6–7 years).

-

Parents helped their children grow socially and emotionally by spending time with them, sharing positive relationships, and giving advice and support.

-

The majority of parents felt they spent enough time with their children and corresponding numbers of children thought their parents spent the right amount of time at work.

Dr Jennifer Baxter is a Senior Research Fellow, Dr Daryl Higgins is the Deputy Director (Research) and Professor Alan Hayes is the Director, all at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Baxter, J., Higgins, D., & Hayes, A. (2012). Families make all the difference: Helping kids to grow and learn (Facts Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-922038-00-5