Mothers with young children

Should they work? Do they want to work?

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 1991

Abstract

Drawing on data from the 1989 National Social Science Survey this article looks at women's employment when they have preschool children. The subject is considered from a number of angles. First, women's preferences for work at this stage and the preferences of men for their wives' employment. Second, these preferences are compared to what women and men consider is best for the average woman. Third, for those women who have a preschooler at the time of the survey, preferences are compared with actual employment status.

Women holding down paid jobs is not a recent phenomenon. They have been employed for decades, but what has changed significantly is that they are working at different stages in their lives.

Rather than the female workforce consisting mainly of women who either have adult children or are childless, recent decades have witnessed a growing proportion of employed women with children, especially young children. Recent statistics show that 42 per cent of mothers with children aged newborn to four are employed (ABS 1990).

An article on family values in the August edition of Family Matters presented some findings about attitudes toward working mothers (VandenHeuvel 1991). It was shown that some of the traditional, more conservative views towards working mothers still exist. For instance, about half the respondents thought that pre-school children were likely to suffer if their mother worked, and the same percentage thought that family life suffered when a woman worked full- time. Just more than 30 per cent agreed that a woman should devote almost all of her time to a family.

To expand on these findings, this article looks at women's employment when they have pre-school children traditionally the life stage when most feel it is best for the mother to forgo a paid job outside the home.

This subject is considered from a number of different angles. First, women's preferences for work at this stage are presented. The preferences of men for their wives' employment follow, since women's decisions in this regard are not made without taking into account familial concerns and opinions.

Second, these preferences are compared to what women and men consider is best for the average woman. Third, for those women who had a pre-schooler at the time of the survey, preferences are compared with actual employment status.

The data set used is large and nationally representative: the 1989 National Social Science Survey. The sample is a randomly selected group of 4511 adult Australians; 51 per cent of these were women. The data were collected by researchers at the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University. The Institute was one of the sponsors of the survey.

Employment Preferences

Understanding preferences with regard to the employment of women is important for a number of reasons. Employment preferences touch many aspects of the life of a woman and her family (Spitze and Waite 1981). For instance, a desire for continuous employment may cause a woman to delay marriage, delay childbearing, or limit the number of children she has.

In addition, preferences affect actual participation. One's desire to work or not may affect, among other things, the number of hours worked, the occupation chosen, or the stability of employment over the years. Further, attitudes toward, and enjoyment of, the activity mothers are engaged in, be it employment or staying at home with children, will be influenced by preferences for that particular activity.

In the Social Science Survey, respondents were asked to give their preferences for their own (if female) or their wife's (if a male respondent) employment at various stages of life, one of which was when there were pre-school children in the home. There were three response options: work full-time, work part-time, and stay home.

The large majority (69 per cent) of respondents preferred that the mother stay home when she had pre-school children. The other two options were far less popular. Working part-time attracted just more than a quarter of the respondents (28 per cent). Few (4 per cent) preferred full- time employment at this stage.

The responses given by men and women were similar; that is, there is no statistical difference between the responses they gave. Thus men and women tended to agree on the preferred role for young mothers.

The gender of the respondent does not make a difference but does age? Respondents were categorised into three age groups: 18 to 34, 35 to 49, and 50 and older. A clear trend was evident by age; the direction of the trend was as expected. For both men and women, older respondents were significantly more likely than younger respondents to prefer mothers with pre-schoolers to stay at home and less likely to prefer part-time employment at this stage. For instance, about 60 per cent of the younger respondents preferred mothers to stay home with young children; more than 80 per cent of the older respondents were of the same opinion.

Many of the respondents who at the time of the survey had a pre- school child or did not have a child were in the younger age group. A closer look at these women is warranted as they will be the ones setting the trends in the 1990s.

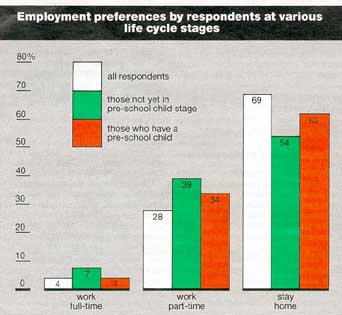

Figure 1 compares the responses of the general population to those of respondents in the above two stages. First, if we look at younger women who did not have a child (defined to be childless women aged 40 years or less), we see that fewer prefer to stay home compared with the preference of the general population. Also, their preference for part-time work for mothers of pre-schoolers is higher.

Next, we can look at those who actually had a pre-school child at the time of the survey. These women, compared with those who had not reached this stage yet, were more likely to prefer to stay home and less likely to prefer employment.

Differences according to which stage the respondent is in are evident. Those who had not yet had children were the most likely to prefer employment when children were pre- school aged. Can we then expect participation rates for young mothers to continue to increase in the future? Possibly. This finding, along with the fact that more and more young women are gaining higher education, are pursuing careers, and are realising the financial necessity of work when they have young children, makes such a scenario quite feasible. Thus it would not be a surprise to see the percentage of young mothers who hold down jobs grow during the 1990s.

But we need to consider the possibility that preferences stated by these childless women might change. That is, once they have a child, they may be more likely to prefer to stay home and thus have preferences similar to those stated by the women already in this stage. However, earlier research suggests that if there is a change in a woman's work preferences after having a first child, it is most often in the direction of a greater preference for employment (Spitze and Waite 1981).

This may be because once in the stage, there is a more realistic appreciation of the costs (financial and other) involved in staying home with young children; as a result, preferences for work increase. Thus if there is a post-birth change in women's preferences, it is more likely to be towards more rather than less involvement in the workforce.

Should Mothers with Young Children Work?

Another question asked in the Social Science Survey was 'Do you think that women should work outside the home full- time, part- time, or not at all under these circumstances ... when there is a child under school age?'

Note that this differs from the question on preferences. Asking people what a person 'should' do is a more general question than asking what they themselves prefer to do. A certain action may be considered to be best for another person but not preferred for oneself.

Yet in this instance, preferences and general attitudes were most often the same. In 83 per cent of the cases, responses to the two questions were identical. The most common instances in which responses did not match was when part- time employment was chosen in one case but staying home in the other.

Thus we see that when considering employment for mothers with young children, what respondents prefer for themselves or their wives is most often what they think women in general should do. There do not seem to be two sets of guidelines (one for themselves and one for others) on this matter.

Actual Work Activity

How do preferences for employment compare with what mothers actually do? Respondents were asked: 'Did you work outside the home full-time, part-time, or not at all at these different times of life ... when a child was under school age?' For those women who at the time of the survey had a pre-school aged child (18 per cent), responses to this question were compared with their employment preferences.

Table 1 presents the result of this comparison. Looking first at employment status, we see that the women most commonly stayed at home (47 per cent). This was followed closely by part-time work (40 per cent). A further 13 per cent worked full-time.

| Per cent | ||

| Employment preference | Employment activity | |

| Work full time | 4 | 13 |

| Work part time | 34 | 40 |

| Stay home | 62 | 47 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Source: National Social Science Survey 1989 | ||

How does this compare to preferences? The answer is 'not very closely'. The percentage preferring full-time work (4 per cent) is significantly less than the percentage actually working full-time (13 per cent). Many more mothers preferred to stay home than were actually doing so; that is, 47 per cent were at home with their pre- school children while 62 per cent preferred to be doing so.

Another way to compare preferences with what mothers actually did is to match responses to the two questions for each individual. Table 2 presents the results of such a comparison. For 63 per cent of the women, preferences matched action. Thus for the remainder, more than a third, preferences did not match reality. The most common case in which responses did not match was when a woman preferred to stay home but actually worked part-time (18 per cent). The reverse was also fairly common (8 per cent).

| Preferred Activity | Actual Activity | Per cent |

| full time work | full time work | 3 |

| part time work | part time work | 21 |

| stay home | stay home | 39 |

| stay home | part time work | 18 |

| part time work | stay home | 8 |

| part time work | full time work | 6 |

| stay home | full time work | 5 |

| full time work | part time work | 1 |

| Source: National Social Science Survey 1989 | ||

Conclusion

The large majority of Australians think that mothers with young children should stay home and most prefer the same thing for themselves. For those who did desire employment, the preference was almost always for part-time rather than full-time work. There is a clear picture that the ideal situation for families with pre-schoolers is the mother staying home, or, at least, not spending most of her day at a job.

Yet, when we look at the actual employment status of mothers of young children, we see that preferences are not always realised. Less than half of these mothers were actually at home during this period. Less than two-thirds were engaged in their preferred option. Thus for more than a third of the mothers of pre-school children, preferences did not match actual employment status.

Why is it that so many mothers of pre-schoolers are not fulfilling their preferences? A number of reasons can be suggested. Financial concerns may force a mother to work despite a desire to stay home, or to work more hours than preferred. Those preferring part-time work may not have been able to find a job with such hours. The lack of suitable day care facilities, accessible transport or other such factors may have discouraged employment for some who desired it. For others, the preferences of other family members may have encouraged the mother to act against her own preferred options. Whatever the reason, the fact that preferences are not realised is an important issue it may have negative effects on the woman, on the family, and on the work place.

The people most in favor of employment when there are young children in the home are those who have not yet reached this stage. If their preferences remain stable over time, or even change in favour of work, and if the majority of young mothers continue to realise their employment preferences, even higher rates of their employment can be expected for the 1990s. Such an increase would have broad effects on such matters as the need for child care facilities, the demand for more flexible policies in the workplace, and the continuity of women's participation in the workforce over time.

References

- ABS (1990), Labour Force Status and Other Characteristics of Families, Australia, June 1990, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Spitze, G.D. and Waite, L.J. (1981), 'Young women's preferences for market work: response to marital events', Research in Population Economics, Vol.3, pp.147166.

- VandenHeuvel, A. (1991), 'The most important person in the world', Family Matters, No.29, August.