Living-apart-together (LAT) relationships in Australia

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

April 2011

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

The past few decades have seen substantial changes in relationship formation and dissolution patterns in Australia, as in other Western countries, including the postponement and decline of marriage and the increasing popularity of cohabitation. These trends have also led to a change in what demographers and social researchers define as being in a union or relationship. In the past, the distinction was between those who were married versus those who were single (never married, separated, divorced or widowed). Today, a tripartite model is typically used instead, differentiating between those who are single, cohabiting or married (Hakim, 2004; Rindfuss & VandenHeuvel, 1990; Roseneil, 2006). In this model, anyone not living in the same residence as a partner is classified as being single. This perspective is reinforced by social surveys oriented toward collecting data about households and the relationship of individuals within those households (Asendorpf, 2008; Strohm, Seltzer, Cochran, & Mays, 2010).

However, a growing body of research is now accumulating on another form of partnership that is not easily accommodated within this tripartite relationship model—that of people who are in “living-apart-together” (LAT) relationships; that is, those who identify themselves as being in a relationship with someone with whom they do not live (Trost, 1998). Such relationships are also sometimes described as non-cohabiting or non-residential relationships. Individuals in these unions are essentially “hidden populations”, not registered in any official statistics (Borell & Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, 2003). This makes it difficult to estimate how common they are, but survey evidence from a range of countries suggests that a substantial percentage of the population that would typically be classified as single is in fact in a LAT (non-cohabiting or non-residential) relationship. In Australia, nationally representative surveys indicate that between 7% and 9% of the adult population has a partner who does not live with them.1

Interest in LAT relationships has only recently emerged and there remain questions as to how these relationships should be defined and accommodated, at both a conceptual and theoretical level. As Haskey & Lewis (2006, p. 38) noted, LAT raises many of the same kinds of questions that were raised when cohabitation first came to be widely recognised as a distinct form of partnership. These questions relate to both the characteristics of the individuals involved as well as the meaning of the relationships themselves; whether they are a transitional stage before cohabitation or marriage, or a completely new form of partnership. Evidence suggests that individuals enter into non-residential relationships for a range of different reasons throughout the life course.

To date very little is known about non-cohabiting relationships in Australia, because of the lack of nationally representative survey data on this topic. For the first time in Australia, questions on LAT relationships were asked in the 5th wave (2005) of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. We used these data to examine LAT relationships, with the aim of providing an estimate of their prevalence, investigating the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of individuals in these unions, and examining how the meaning attached to these unions varies across the life course.

Background

According to Levin (2004), the LAT relationship is a “new family form” that existed in the past but in recent years has become much more prevalent and visible in society. Due to the lack of historical data on the prevalence of LAT relationships, it is difficult to know with certainty if there has been a real rise in the prevalence of non-residential unions, or whether this form of relationship has simply begun to attract more attention than before (Ermisch & Siedler, 2008). Evidence from a Swedish poll conducted in 1993, 1998 and 2001 appears to show an increase in the prevalence of non-residential relationships (Levin, 2004), and increases between 1982 and 1997 have also been reported for Japan (Iwasawa, 2004). However, no increasing trend was found between 1991 and 2005 in a study using the German Socio-Economic Panel (Ermisch & Siedler, 2008). Despite the somewhat mixed evidence, there are good reasons to believe that non-cohabiting unions have become increasingly common in recent years, while at the same time the recent academic and media interest in these relationships has also made them more visible.

One reason why LATs may be more prevalent today is the simple fact that a growing proportion of the population is now unpartnered at any point in time (Weston & Qu, 2006). For example, between 1986 and 2001, the percentage of women aged 30–34 who were unpartnered (not cohabiting, not married) increased from 23% to 34% (de Vaus, 2004), while for men in their early 30s, the equivalent rise was from 29% to 41%. As a larger proportion of the population is not in a cohabiting or marital union, the proportion of the population that is “at risk” of forming a non-residential relationship has also increased. Factors contributing to the increased prevalence of individuals who are unpartnered, include socio-economic changes such as the prolonging of time in education, demographic trends such as increased life expectancy, and increased rates of relationship dissolution through divorce or the breakdown of cohabitations (Castro-Martín, Domínguez-Folgueras, & Martín-García, 2008; Milan & Peters, 2003; Weston & Qu, 2006). At the same time, ideational changes have made alternative forms of partnerships more acceptable in society, and couples who find themselves in a relationship with a new partner who lives elsewhere may not feel as great a social pressure as they would have in the past to settle down together in a common residence (Levin, 2004).

The greater availability of quantitative data from social surveys as well as qualitative studies has also made these relationships more visible (Haskey & Lewis, 2006; Trost, 1998). Until recently, the majority of research on LAT relationships originated from Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden and Norway (Levin & Trost, 1999) where this type of union has long been socially recognised and accepted as a distinct type of relationship (Borrel & Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, 2003). However, with the dramatic increase in interest in LATs during the past few years, research is now also accumulating from a growing list of countries, including France (Beaujouan, Regnier-Loilier, & Villeneueve-Gokalp, 2009), Germany (Asendorpf, 2008), Spain (Castro-Martin et al., 2008), United Kingdom (Duncan & Philips, 2010; Ermisch & Siedler, 2008; Haskey 2005; Haskey & Lewis, 2006), Canada (Milan & Peters, 2003), the United States (Strohm et al., 2010) and Japan (Iwasawa, 2004).

In terms of prevalence, evidence suggests that a substantial minority of the total adult population is involved in a LAT relationship. For example, in the US, data from the General Social Survey of 1996 and 1998 indicate that 6% of women and 7% of men are in a LAT relationship (Strohm et al., 2010), and the 2001 Canadian Social Survey produces similar estimates of 8% of the population aged 20 and over being in a LAT relationship (Milan & Peters, 2003). Direct international comparisons of the prevalence of LAT relationships are difficult to make, however, because of the differences in the age ranges of the analytical samples, the dates of the surveys, and the definitions of LAT used. Due to the relatively recent emergence of scholarly interest in non-cohabiting unions, there is still a lack of consensus regarding their precise definition.

Definition

With regard to definitions, one of the most important questions in the recent literature is where, if anywhere, the boundary between casual dating relationships and more committed LAT relationships should be drawn. In general, there is some agreement that more casual and fleeting relationships should be differentiated from more committed non-residential unions, and often different terms are used to make a theoretical distinction between the two. For example, Haskey (2005) termed the former as “those who have a partner who usually lives elsewhere”, and the latter as LAT relationships. Similarly, Trost (1998) used the term “steady going couples” to identify casual relationships, as distinct from the more committed LAT couples. However, in practice, trying to categorise respondents into one group or the other is very difficult. Various factors have been used by researchers as proxy indicators of the level of seriousness of the relationship. In their study of young people in Spain, Castro-Martin et al. (2008) excluded LAT relationships that had lasted for less than two years, while Haskey (2005) used a number of alternative ways to try and estimate the “true” number of LATs from the Omnibus Survey in Britain, such as by excluding the relationships of young adults who were still living at home.

Since quantitative data on non-residential unions come from surveys, question wording plays a very important role in determining how such unions are defined and enumerated. As Haskey (2005) recognised, it would be impossible to simply ask survey respondents whether they were in a “living-apart-together” relationship as most people would not understand the term without some explanation and elaboration. Instead, surveys have used a variety and combination of terminologies to distinguish dating relationships from more committed unions (Strohm et al., 2010). Examples include:

- “Do you have a main romantic involvement—a (man/woman) you think of as a steady, lover, a partner, or whatever?” If yes, respondents are asked if they live with their partner. (1996 & 1998 US General Social Survey)

- “Are you in an intimate relationship with someone who lives in a separate household?” (2001 Canadian Survey)

- “Do you have a steady relationship with a male or female friend whom you think of as your ‘partner’, even though you are not living together?” (1998, 2003 & 2008 British Household Panel Survey)

- “Are you currently in an intimate ongoing relationship with someone you are not living with?” (Generations and Gender Survey (GGS); 2005 & 2008 HILDA)

The degree to which these questions are able to exclude less committed relationship varies. The last question, which was included in HILDA, is probably one of the strongest as it includes the terms “intimate” and “ongoing”. Nevertheless, unlike questions on more objective concepts, such as legal marital status, it is inevitable that even the clearest question about non-residential unions will involve an element of subjectivity (Haskey, 2005).

An important theoretical question regarding LATs relates to the meaning of these partnerships and whether they are a transitory step taken before entering a live-in relationship, or whether they represent a more permanent arrangement. A closely related distinction is whether partners are living apart voluntarily, through an active choice, or involuntarily due to constraining circumstances (Levin, 2004). Previous research suggests that the meaning of LAT relationships and the reasons why individuals enter into them, depends very much on what stage of the life course an individual is at (Beaujouan et al., 2009; Strohm et al., 2010).

LAT relationships appear to be more provisional and involuntary among younger cohorts. The geographic location of places of work or study, as well as financial and housing factors may prevent young people from moving into a joint residence with their partner. Involuntary relationships may also be the result of having caring responsibilities for children or elderly parents (Levin, 2004). While these circumstances prevent moving in together, for these individuals the possibility of cohabiting in the future is there if and when circumstances change.

Alternatively, LAT relationships can be more permanent arrangements that allow for intimacy but also autonomy and independence, and this appears to be particularly the case for older individuals (Levin, 2004). Other reasons for actively wanting to live apart include the feeling of not being ready to live with someone, and having concerns about children (Beaujouan et al., 2009). Qualitative evidence suggests that those who are voluntarily living apart include individuals who have already gone through a divorce or a relationship breakdown—experiences that have left them particularly “risk averse” (de Jong Gierveld, 2004; Levin, 2004; Roseneil, 2006).

While useful, the distinction between LAT relationships that are involuntary and those that are more voluntary and permanent arrangements, might not always be clear cut. Based on a qualitative study of LATs in the United Kingdom, Roseneil (2006) suggested that apart from these two main groups of LATS—the “regretfully apart” and the ‘gladly apart’—there is also a large group of individuals who are “undecidedly apart”. People in this group have not made a definite choice to cohabit or not. Some speak of not being ready or of fearing that cohabitation may ruin their relationship; reasons that have also been mentioned in other qualitative studies (Haskey & Lewis, 2006). As Haskey & Lewis noted, fear and perceptions of risk are important considerations, because in many ways the “leap of faith” needed for moving from a LAT relationship to a cohabiting one is greater than the one needed to transition from cohabitation to marriage.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the nature and pattern of LAT relationships in Australia. The first objective was to determine the prevalence of non-residential relationships in Australia and to describe the key features of these relationships, including their duration, the frequency of contact and the geographic distance between partners. We then identified a typology of four types of individuals at different stages of their life course who were in LAT relationships, and investigated how the meaning and purpose of non-residential relationships varied across these four types of people. If the nature and pattern of LAT relationships in Australia is similar to that found from research in other Western countries, we would expect that for younger individuals, a LAT relationship is likely to be a transitional relationship, or a step towards cohabitation, while for older individuals it may be a more voluntary and permanent arrangement.

Data and method

Data

To investigate the prevalence and characteristics of non-residential unions in Australia, we used data from the 5th wave of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. HILDA is a large-scale nationally representative longitudinal survey that is conducted on an annual basis and interviews all members of a household aged 15 and over. In the 5th wave, several key questions were included for the first time as part of Australia’s participation in the international Generations and Gender Survey (GGS), a cross-national longitudinal survey coordinated by the Population Activities Unit of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

The question in HILDA asked respondents who were not married and not living with a partner, whether they were in an intimate ongoing relationship with someone with whom they were not living. Respondents who answered yes were then asked a series of more detailed questions regarding their relationships, including: the month and year the relationship started, whether a definite decision to live apart had been made (and if yes by whom), the geographic distance to the partner, and the frequency of contact. Respondents were also asked if they intended to start living with their current partner during the next three years, and if they planned to marry in the future.

It is important to note that the questions on non-residential partnerships were restricted to those who were not married, unlike in the standard GGS questionnaire, where the possibility that a respondent is married and in a relationship with their spouse but not living with them is included.2 The questions were asked of both heterosexual and same-sex couples, and we have included both types of couples in this study.3 Also, we made no specific distinction at the outset between more and less casual relationships; all living-apart-together relationships were considered, even if they had only been ongoing for a short time. The total sample size in Wave 5 was 12,759 individuals, but as relationship questions were only asked of respondents aged 18 or over, or less than 18 but not living with parents, we excluded all those aged less than 18. This resulted in a total analytical sample of 12,066 respondents, of which 974 were in a LAT relationship.

Method

The analysis is undertaken in two parts. The first section describes the prevalence and characteristics of LAT respondents compared to those who are single, cohabiting or married, using weighted percentages and summary statistics. Three important aspects of LAT relationships are also investigated and compared by age: relationship duration, frequency of contact and geographical distance between partners. In the second section, we use multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) and cluster analysis to identify different profiles of respondents with similar demographic characteristics. These different groups of individuals are then compared in terms of differences in their intentions for the future of their relationships.

Creating a typology of LATs

To create a typology of individuals in LAT relationships, we followed the strategy used by Beaujouan et al. (2009), who analysed the French GGS data and used multiple correspondence analysis. MCA is a method of identifying patterns among three or more categorical variables (Greenacre, 2007), which works by converting contingency tables into a low-dimensional (typically two-dimensional) space or map.4 The proximities, shown graphically on the map, can then be interpreted. In this case, we were interested in the interrelationship between four key demographic variables of individuals in LAT relationships: their sex, their age, the presence of children, and previous relationship history. Age is divided into four categories. The presence of children is described by a three-category variable indicating whether the respondent had no children, at least one resident child, or only non-resident children. Finally, previous relationship history was divided into three categories, consisting of those previously married, previously cohabited but never married, and never cohabited or married.

Based on the results of the MCA, Ward’s cluster analysis of the coordinates of the observations was used to group together respondents with similar characteristics. We identified four types of individuals with similar demographic characteristics and, using these groups, we investigated how the groups differed in their answers to three key questions: whether or not they have made a definite decision to live apart, whether they intend to live together within the next 3 years, and whether or not they intend to marry. This allowed us to see whether their relationship was voluntary or involuntary, and the degree to which it was seen as a transitional or permanent arrangement. We used MCA and cluster analysis rather than regression methods to examine demographic differences in relationship intentions because of the high multicollinearity between many of the variables in which we were interested.5

Results

Prevalence and characteristics of LATs

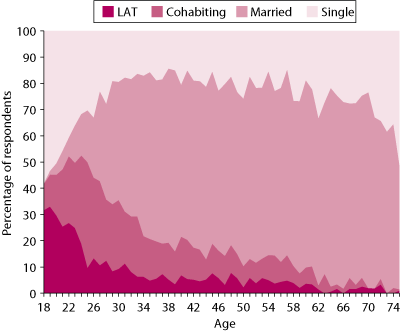

The distribution of the HILDA sample according to their relationship status (single, married, cohabiting or LAT) by age, is shown in Figure 1. The graph shows a clear pattern between age and relationships status, with the proportion that were in a LAT or cohabitating relationship declining with age, and the proportion in a marriage increasing.6 Of those aged 18 and over, 36% were not married or cohabiting, a figure that is similar to the 39% estimated by the 2006 Census (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2009). The overall percentage of the sample that was in a non-cohabiting union was 9%, which represents 24% of those who were not cohabiting or married.

Figure 1 Relationship status, by age (18–75+ years)

Source: HILDA Wave 5

Apart from age, relationship status was also related to several other key demographic and socio-economic variables, as shown in Table 1. Compared to those who were single, cohabiting or married, those in a LAT relationship differed on several key characteristics. They were less likely to have children compared to those who were married, cohabiting or single, and they were also less likely to have ever been married. Their marital and fertility history is, of course, closely related to their young age profile.

| Single % (weighted) | LAT % (weighted) | Cohabiting % (weighted) | Married % (weighted) | Total % (weighted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 25 | 44 | 16 | 1 | 13 |

| 25–29 | 10 | 14 | 19 | 5 | 9 |

| 30–34 | 8 | 14 | 19 | 10 | 10 |

| 35–39 | 7 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 10 |

| 40–44 | 7 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 10 |

| 45+ | 44 | 16 | 25 | 61 | 49 |

| Number of children | |||||

| 0 | 55 | 73 | 50 | 11 | 32 |

| 1+ | 45 | 27 | 50 | 89 | 68 |

| Ever married | |||||

| Yes | 43 | 21 | 28 | 100 | 71 |

| No | 57 | 79 | 72 | 0 | 29 |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 55 | 82 | 79 | 62 | 64 |

| Unemployed | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Not in the labour force | 39 | 14 | 18 | 36 | 34 |

| Highest education | |||||

| University | 16 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 21 |

| Certificate/diploma | 26 | 30 | 34 | 32 | 30 |

| Year 12 | 21 | 30 | 17 | 12 | 16 |

| Year 11 or below | 37 | 18 | 26 | 34 | 33 |

| Total percentage | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total N (unweighted) | 3,290 | 974 | 1,509 | 6,293 | 12,066 |

Source: HILDA Wave 5

People with a non-cohabiting partner had a similar employment status to those who were cohabiting, and the education profile of the LATs was also similar to both cohabiting and married individuals. However, the percentage of LATs who were only educated up to Year 11 or below, was lower than for the relationship status of the other groups. This could be due to a cohort effect, since younger people have higher education levels than older cohorts; however, it might also be that LAT relationships are simply more prevalent among those with higher educational levels, as other studies from the United Kingdom, Spain and Germany have found (Castro-Martin et al., 2008; Ermisch & Siedler, 2008; Haskey & Lewis, 2006). A possible reason for this is that individuals with higher education and occupational statuses are more likely to have jobs that require a degree of travel and mobility, and at the same time they are more able to afford two separate residences (Haskey & Lewis, 2006). Castro-Martin et al. (2008) also suggested that among younger individuals in Spain LAT arrangements may suit those who prioritise a professional career.

Duration, frequency of contact and distance between partners

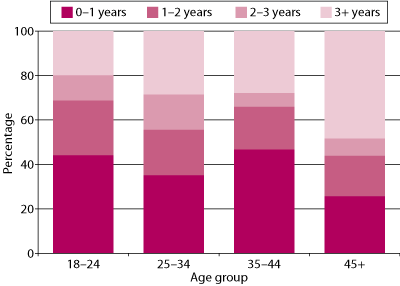

At the time of the survey, the majority of LAT relationships had, on average, been ongoing for only a short amount of time;7 the mean duration of these relationships was 2.4 years, and the median was 1.5 years. These averages, however, hide quite substantial variations in relationship durations. While the majority of respondents (40%) had began their relationship less than 12 months before the survey, a substantial 28% were in a relationship that had lasted for 3 years or more. The cross-sectional nature of the data makes it difficult to draw any conclusions about the timing of transitions out of non-cohabiting relationships, but the results seem to indicate that after one or two years, individuals in non-resident relationships commonly experience some transition, either by ending the relationship or by starting to live together. How long a LAT relationship had been ongoing was closely related to a person’s age, as shown in Figure 2. In particular, those aged 45 and over stood out, as nearly half of the people in this age group were in a relationship that had lasted 3 years or more, compared to less than a third of respondents in all the other younger age groups.

Figure 2 Duration of LAT relationship, by age group

Source: HILDA Wave 5

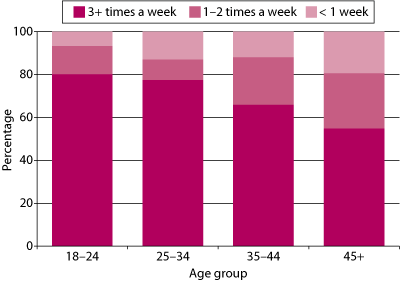

Another important characteristic of LAT relationships that we considered was how frequently the partners met. The frequency of contact between partners gives us some indication of the importance of a LAT partner to an individual’s daily life. We found that despite not sharing the same residence, the frequency of contact between partners was very high, with around 75% of individuals meeting their partners at least three times a week, and many of these on a daily basis.

As with the duration of the relationship, the frequency of contact also showed some variation by age, as shown in Figure 3 (on page 50). The association with age was negative, with those aged under 35 meeting their partners most often. At these ages, the two partners may be attending the same school, university or workplace, which would allow them to meet their partner on a frequent basis. The relatively less frequent contact among those over 35 could also be related to the fact that these older respondents are also the ones who are more likely to have resident children, and would therefore experience greater time constraints. Nevertheless, even among those aged 45 and over, around 80% still saw their partner on a weekly basis.

Figure 3 Frequency of contact between partners, by age group

Source: HILDA Wave 5

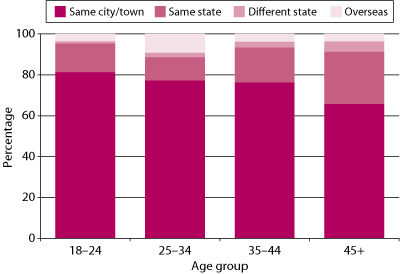

A key factor regulating the frequency of contact between partners was how close they lived to each other. As might be expected from the high frequency of contact, the majority of people with a non-residential partner lived very close by to their partners. Nearly three-quarters lived in the same city as their partner, and a further 15% lived in different cities in the same state. Only a minority were in a long-distance relationship with a partner who lived in another state (2%) or overseas (5%). The close physical proximity between partners’ residences was also indicated by the travel time between residences. Around one quarter of individuals lived less than 10 minutes away from their partners, with the median time being 20 minutes.

The relationship between age and geographic location between partners is shown in Figure 4. Out of all age groups, those aged 45 and over were the most likely to be living in different cities, which would also explain the lower frequency of contact mentioned above. It is interesting to note that among the 25–34 year age group, just under 10% had a relationship with someone living abroad. It could be speculated that this is related to the relatively high degree of travel undertaken at these ages (ABS, 2008). These respondents may have met a partner while travelling or working overseas, or their partner may have moved overseas for travel or work reasons.

Figure 4 Geographic distance between partners, by age group

Source: HILDA Wave 5

Typology of LATs

Our next step was to identify a typology of individuals in LAT relationships. From the MCA and cluster analysis, we identified four main types of individuals, whose characteristics are shown in Table 2. We called the first group the “Under-25s” because they were primarily made up of individuals aged 18–24. This group was relatively homogenous, having had no children, no previous history of marriage, and, for the most part, no history of cohabitation. The second group we termed “Young adults, previously de facto”. As the name implies, this group was primarily made up of young adults between the ages of 25 and 34, the majority of whom were childless and had no marriage history, but usually had experienced at least one cohabitation in the past. The third type was the “Single parents”, who were older people, typically over 30, most of whom had been married and had at least one child resident in the household. Finally, we identified the “Older, previously married” group, which was also relatively homogeneous, consisting mainly of those aged 45 and over who had previously been married. Our typology of individuals was very similar to the one derived from the French GGS (Beaujouan et al., 2009).

| Under-25s % | Young adults, previously de facto % | Single parents % | Older, previously married % | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 63 | 28 | 48 | 65 | 53 |

| Female | 37 | 72 | 52 | 35 | 47 |

| Age group | |||||

| 18–24 | 75 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 44 |

| 25–29 | 13 | 32 | 5 | 0 | 14 |

| 30–34 | 9 | 35 | 12 | 0 | 14 |

| 35–39 | 2 | 10 | 15 | 0 | 6 |

| 40–44 | 1 | 9 | 20 | 0 | 6 |

| 45+ | 0 | 0 | 46 | 100 | 16 |

| Number of children | |||||

| 0 | 100 | 74 | 19 | 0 | 73 |

| 1+ | 0 | 26 | 81 | 100 | 27 |

| Ever married | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 73 | 100 | 79 |

| No | 100 | 100 | 27 | 0 | 21 |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 85 | 78 | 82 | 69 | 82 |

| Unemployed | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Not in the labour force | 10 | 17 | 17 | 29 | 14 |

| Highest education | |||||

| University degree | 20 | 28 | 23 | 19 | 22 |

| Certificate/Diploma | 25 | 39 | 33 | 38 | 30 |

| Year 12 | 40 | 21 | 17 | 12 | 30 |

| Year 11 or below | 15 | 12 | 28 | 31 | 18 |

| Total percentage | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total N (unweighted) | 474 | 184 | 219 | 97 | 974 |

| Within-class variance | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.16 | |

Source: Hilda Wave 5

Intentions to cohabit or marry

Based on our typology of individuals, we then examined group differences in whether a definite decision had been made to live apart, and in their future intentions to cohabit or marry. We found clear differences between the group responses, including whether they had made a definite decision to live apart, as shown in Table 3. For example, while over 70% of the older respondents who had previously been married had made a positive decision to live apart, this was the case for less than half of the under-25s.

To some extent, a definite decision to live apart could be taken as implying that the arrangement of not living in the same household was one of choice rather than constraint. However, this may not always be clear-cut, because young adults still living at home may have stated that they had made a definite decision to live apart, as opposed to a preferred choice, but only because of constraints such as lack of financial resources that prevented them from moving in with their partner.

When there had been a definite decision to live apart, most people indicated that it was a joint decision between them and their partner. The single parents were most likely to state that the decision to live apart was solely theirs, followed by the older group. While the responses of the single parents are not surprising, it is interesting that in the other groups where the decision was not joint, individuals usually stated that it was their decision alone, even though we would expect the decision to be roughly equally divided between the two partners.

Turning to people’s intentions regarding the future of their relationships, nearly two-thirds of respondents planned to live together within the next 3 years, although there was large degree of variation in responses (Table 3). The young adults were the group with the highest stated intentions of living with their partner, at 79%, while the lowest intentions were found among the older group, at 32%.

| Under 25s | Young adults, previously de facto | Single parents | Older, previously married | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite decision to live apart | |||||

| Yes | 48 | 61 | 67 | 73 | 57 |

| No | 52 | 39 | 33 | 27 | 43 |

| Total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total (N) | 474 | 184 | 219 | 96 | 973 |

| Whose decision to live apart | |||||

| Respondent | 11 | 15 | 23 | 17 | 16 |

| Respondent's partner | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Both respondent and partner | 87 | 81 | 72 | 76 | 80 |

| Total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total (N) | 229 | 111 | 147 | 70 | 557 |

| Intend to live together within next 3 years | |||||

| Yes | 69 | 79 | 53 | 32 | 64 |

| No | 31 | 21 | 47 | 68 | 36 |

| Total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total (N) | 468 | 178 | 210 | 90 | 946 |

| Likelihood of marrying/re-marrying | |||||

| Unlikely/very unlikely | 6 | 12 | 44 | 68 | 22 |

| Not sure | 23 | 31 | 24 | 17 | 24 |

| Likely/very likely | 71 | 57 | 32 | 16 | 54 |

| Total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total (N) | 473 | 182 | 216 | 97 | 968 |

Source: Hilda Wave 5

In general, it is difficult to tell whether those who stated that they did not intend to live together in the next 3 years were just uncertain if their relationship would continue that far into the future, or whether their answer was more an indication of a preference to maintain the status quo and stay in the relationship in the long term but continue living in separate residences. Given the earlier results regarding the age pattern of duration, it may be speculated that for young adults a negative intention reflects an uncertainty about the future of the relationship, while for older adults—who had relationships of the longest duration—it could indicate a preference to keep the current living arrangements.

It is also interesting to note that there was not always a close link between having made a definite decision to live apart and intentions to not live together at all. For example, while 61% of young adults (previously de facto) had made a decision to live apart, around 79% did intend to move in together within the next 3 years.

Respondents were also asked about their plans for marriage in the future. There was no explicit mention in this question whether the future marriage was to the current LAT partner or to a hypothetical future partner; we assumed that the majority would answer with respect to their current partner. As with the intention to cohabit, responses to the marriage question also varied greatly among the groups. Among the under-25s group, just over 70% thought that they were likely or very likely to marry in the future, and attitudes towards marriage were also positive among young adults who had previously been de facto. On the other hand, single parents and older respondents had much lower intentions of marrying, a result that was also found by Ermisch & Siedler (2008). Over two-thirds of the older respondents said they were unlikely or very unlikely to remarry in the future.

Discussion

The results from the analyses of HILDA data closely resemble the ones from other international studies. In particular, we find that older respondents, most of whom were widowed or divorced, were the most likely to be “voluntarily” living-apart-together and to have little intention to transition into cohabitation. While we do not know the reasons behind the choice, the wish to maintain a degree of independence and autonomy is likely to be an important consideration (Beaujouan et al., 2009). Qualitative research of LAT relationships in later life in other countries highlights that for the elderly, important concerns appear to centre around the practicalities of sharing living quarters with someone else and having to adjust to another person’s habits, and the wish to remain autonomous and maintain or continue relationships with children and grandchildren (de Jong Gierveld, 2002).

The single parents most closely resembled the older respondents in their decision to live apart and their future plans for cohabitation. Again, we do not know the reasons behind the decision, though it is possible that they did not want to disrupt the home environment of their resident child(ren) by bringing a new partner into the home or by moving into another residence. Around half of the single parents did, however, envisage living with their partner in the next 3 years. At this time, the resident children may have grown accustomed to the partner, or they may have grown up and left the household.

A high percentage of young adults who had previously cohabited intended to start cohabiting with their partner in the next 3 years, and also to marry in the future. This group may feel the greatest normative pressure to consolidate their relationship by living in a common residence. For those under 25, the single parents, and the older, previously married, couples, the pressure to move in with their partner is unlikely to be felt as strongly. Indeed, these groups may even have felt a social pressure not to live with their partner.

The under-25s groups was more evenly divided in terms of whether a definite decision had been made to live apart. In this group, we may be picking up a substantial proportion of casual and fleeting relationships. For the more committed partners, the arrangement may be more a matter of circumstances and practical or financial constraints rather than choice. At this age, and with no previous experience of living with a partner, they may also not feel ready to take the step to move in with their partner.

Conclusion

Changing demographic trends mean that a substantial proportion of the population is now not living with a partner. According to the 2006 Census, in Australia 4.6 million people aged 20 and over, or nearly a third of the adult population, were not living with a partner or spouse and could therefore be classified as being unpartnered (ABS, 2007). We estimated from the HILDA data that around 24% of the single population was in fact in a relationship, albeit not living with their partner. This translates to over 1.1 million Australians in living-apart-together relationships. We suggest that it is important to understand more about these partnerships, as the lives of people who are truly single, compared with people who have a non-resident partner, are likely to be different in many respects. Several authors have also predicted that LAT relationships are going to become more common in the future. Reasons for this include the ones discussed earlier, such as the continuation of demographic trends of increased life expectancy, increased rates of marital dissolution and the rise of cohabitations. Also important may be increased gender equality and the rise of dual-career couples, and cases where working women are less able to relocate for their partner’s job (Levin, 2004; Castro-Martin et al., 2008).

For younger individuals, who are known to be moving out of the parental home at increasingly later ages (de Vaus, 2004), it is important to identify the constraints they face in setting up a common residence with their partner, in particular in relation to financial and housing factors. More qualitative research would also be of interest in order to understand young people’s attitudes towards establishing a common residence with a partner, and the degree to which non-residential relationships among young people are related to individualistic values, risk aversion or fear of commitment, as has been suggested (Heath & Cleaver, 2003). Among older individuals, it is also important to learn more about their intimate relationships, because non-residential partners may be an important source of instrumental and emotional support, especially for the elderly who are living alone.

It is important to not only understand more about these relationships in their own right, but also a greater understanding of why new relationship types such as LATs are formed can provide some insight into reasons for changing relationship trends, such as the postponement and avoidance of marriage (Casper, Brandon, DiPrete, Sanders, & Smock, 2008; Strohm et al., 2010). However, to understand the nature of live-apart-together relationships at all stages of the life course, more quantitative and qualitative research is needed. At the moment, our understanding of these relationships is limited by the cross-sectional nature of most quantitative studies. Longitudinal data on LAT relationships would allow us to study their duration, and their possible eventual development into separations or cohabitations.

Endnotes

1 In HILDA Wave 5 (2005), the weighted percentage of those aged 18 and over and with a non-resident partner was 9%. In Wave 4 (2006) of the Negotiating the Life Course survey, the weighted percentage of those aged 18–65 and not living with their partner was 7%. In the Family, Social Capital and Citizenship survey, 7% of the sample had a non-resident partner (unweighted).

2 In the literature, there is no standard treatment of married couples in living-apart-together relationships. Sometimes married couples are included in the definition of LAT unions (Levin & Trost, 1999), and other times excluded (Haskey, 2005). There is general consensus, though, that LAT relationships do not include so-called “commuter” marriages/cohabitations, where the couple maintains one household, but one partner lives elsewhere for periods of time due to work reasons (Levin & Trost, 1999).

3 There were 18 same-sex couples in the HILDA sample (< 2% of those were in LAT relationships).

4 We used the XLSTAT software to perform the multiple correspondence and cluster analysis <www.xlstat.com>.

5 An alternative analysis strategy to that outlined would be to have each of the three key topics of interests (whether relationship is due to a definite decision to live apart, intention to live together in next 3 years, and intention to marry) as the dependent variable and to see how key demographic and socio-economic characteristics—such as age, number of children and employment—influenced the dependent variable. This strategy was not used because of the high degree of multicollinearity between age and the other independent variables; for example, younger respondents are much more likely to have never had a previous live-in relationship and to not have children, while the opposite is true for older respondents. This made it difficult to separate out the effects of age from the other variables of interest.

6 Since these are cross-sectional results, the pattern is influenced by both cohort and age effects.

7 Fifty-nine respondents did not know the month the relationship started, but knew the year. In these cases, the month was imputed to June. In addition, two had missing information on the duration of the relationship, as they did not know the year the relationship started.

References

- Asendorpf, J. B. (2008). Living apart together: Alters- und Kohortenabhängigkeit einer heterogenen Lebensform. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 60(4),749–764.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). 2006 Census tables: Census of Population and Housing: Social marital status by age by sex for time series (Cat. No. 2068.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from <www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/Home/census>.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). Migration, Australia 2006–07 (Cat. No. 3412.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from <www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/3412.02006-07?OpenDocument>.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2009).Couples in Australia (Cat. No. 4102.0). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from <www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/6F761FF864FAA448CA2575830015E923/$File/41020_couples.pdf>.

- Beaujouan, E., Regnier-Loilier, A., & Villeneueve-Gokalp, C. (2009). Neither single, nor in a couple: A study of living apart together in France. Demographic Research, 21(4), 75–108.

- Borell, K., & Ghazanfareeon Karlsson, S. (2003). Reconceptualizing intimacy and ageing: Living apart together. In S. Arber, K. Davidson, & J. Ginn (Eds.), Gender and ageing: Changing roles and relationships (pp. 47–62). Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Casper, L. M., Braddon. P. D., DiPrete, T. A., Sanders, S., & Smock, P. J. (2008). Rethinking change and variation in unions. In P. I. Morgan, C. Bledsoe, S. M. Bianchi, P. L. Chase-Landsdale, T. A. DiPrete, V. J. Hotz et al., (Eds.), Explaining family change: Final report (pp. 59–100). Durham: Duke University. Retrieved from <www.soc.duke.edu/~efc/>.

- Castro-Martín, T., Domínguez-Folgueras, M., & Martín-García, T. (2008). Not truly partnerless: Non-residential partnerships and retreat from marriage in Spain. Demographic Research, 18(16), 436–468.

- de Jong Gierveld, J. (2002). The dilemma of repartnering: Considerations of older men and women entering new intimate relationships in later life. Ageing International, 27(4), 61–78.

- de Jong Gierveld, J. (2004). Remarriage, unmarried cohabitation, living apart together: Partner relationships following bereavement or divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(1), 236–243.

- de Vaus, D. A. ( 2004). Diversity and change in Australian families. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/diversity/main.html>.

- Duncan, S., & Philips, M. (2010). People who live apart together (LATs): How different are they? Sociological Review, 58(1), 112–134.

- Ermisch, J., & Siedler, T. (2008). Living apart together. In M. Brynin, & J. Ermisch (Eds.), Changing relationships (pp. 29–43). New York: Routledge.

- Greenacre, M. (2007). Correspondence analysis in practice. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Hakim, A. (2004, 15–17 September). Social marital status in Australia: Evidence from 2001 Census. Paper presented at the 12th Biennial Conference of the Australian Population Association, Canberra. Retrieved from <www.apa.org.au/upload/2004–7D_Hakim.pdf>.

- Haskey, J. (2005). Living arrangements in contemporary Britain: Having a partner who usually lives elsewhere and living apart together (LAT). Population Trends, 35–45.

- Haskey, J., & Lewis, J. (2006). Living-apart-together in Britain: Context and meaning. International Journal of Law in Context, 2(1), 37–48.

- Heath, S., & Cleaver, E. (2003). Young, free and single? Twenty-somethings and household change. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Iwasawa, M. (2004). Partnership transition in contemporary Japan: Prevalence of non-cohabiting couples. Japanese Journal of Population, 2(1), 76–92.

- Levin, I. (2004). Living apart together: A new family form. Current Sociology, 52(2), 223–240.

- Levin, I., & Trost, J. (1999). Living apart together. Community, Work & Family, 2(3), 279 –294.

- Milan, A., & Peters, A. (2003). Couples living apart. Canadian Social Trends, Summer, 2–6.

- Rindfuss, R. R., & VandenHeuvel, A. (1990). Cohabitation: A precursor to marriage or an alternative to being single? Population and Development Review, 16(4), 703–726.

- Roseneil, S. (2006). On not living with a partner: Unpicking coupledom and cohabitation. Sociological Research Online, 11–3. Retrieved from <www.socresonline.org.uk/11/3/roseneil.html>.

- Strohm, C., Selzer, J. A., Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. (2010). “Living apart together” relationships in the United States. Demographic Research, 21(7), 177–214.

- Trost, J. (1998). LAT relationships now and in the future. In K. Matthijs (Ed.), The family: Contemporary perspectives and challenges (pp. 209–222). Louvain, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

- Weston, R., & Qu, L. (2006). Family statistics and trends: Trends in couple dissolution. Family Relationships Quarterly, 2, 9–12.

Anna Reimondos, A., Evans, A., & Gray, E. (2011). Living-apart-together (LAT) relationships in Australia. Family Matters, 87, 43-55.