The role of planning, support, and maternal and infant factors in women's return to work after maternity leave

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

September 2012

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Workforce participation by mothers of young children is not a new phenomenon; however, few studies have examined factors associated with returning to work after maternity leave, particularly in the Australian context. This study followed 186 pregnant Australian women who intended to return to work within 12 months post-partum, from late in pregnancy until they had returned to work, or their child was 13 months old. With the aim of examining various factors that contribute to women returning to work after maternity leave, factors both internal and external to the woman, and occurring during pregnancy and post-partum were considered. The results indicated that a difficult infant temperament, more planning during pregnancy, greater workplace support, fewer depressive symptoms and anticipating taking a shorter maternity leave differentiated women who did return to work from those who did not. The theoretical implications of the findings, and practical suggestions are discussed.

Workforce participation by mothers - particularly those with young children - is not a new phenomenon. In countries such as the US and Australia, an increase in maternal employment has been evident since the 1960s, although other countries, such as the Netherlands and Spain, did not follow suit until the 1990s (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2007). The benefits from women being employed are broad, as employment is related to improvements in their mental health, physical health, financial resources and social supports (Gjerdingen, McGovern, Bekker, Lundberg, & Willemsen, 2001; Lee & Powers, 2002; Rout, Cooper, & Kerslake, 1997; Schnittker, 2007). Additionally, employers benefit from women returning to work after maternity leave. The costs of replacing an employee are quite high (Davidson, Timo, & Wang, 2010; Tracey & Hinkin, 2008), with estimates of turnover costs ranging from 29% to 46% (Bernthal & Wellins, 2001). Moreover, the costs cited in the literature often do not consider the indirect costs of employee turnover, such as those associated with the initial inefficiency of a new employee, which, when estimated to be approximately 80% of the total cost (Phillips, 1990), far outweighs the direct costs of replacing an employee (Davidson et al., 2010; Phillips, 1990; Scholss, Flanagan, Culler, & Wright, 2009).

It is not surprising, therefore, that interest and research in maternal employment has increased (Skouteris, McNaught, & Dissanayake, 2007), albeit often focused on the potential impact of maternal employment on children's development (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010; Gottfried & Gottfried, 2008; Tan, 2008). Research regarding other aspects of maternal employment - such as work-family conflict and the wage penalty of motherhood - has increased in the last decade (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010); however, few studies have examined factors that are associated with women returning to work after maternity leave, particularly in the Australian context (examples of Australian studies are Baxter, 2005, 2009). Prospective studies and those specifically considering psycho-social factors are lacking.

One factor that has been identified in several studies as influencing whether or not women return to work after having a child is planning during pregnancy (Harrison & Ungerer, 2002; Houston & Marks, 2003), with greater amounts of planning being associated with returning to work, and doing so for the time fraction intended. Coulson, Skouteris, Milgrom, Noblet, and Dissanayake (2010) examined the types and amount of planning done by women during pregnancy for their return to work, and the factors associated with this planning. Information was gathered from 199 Australian women in their third trimester of pregnancy who planned to return to work within 12 months after the birth of their child. The findings revealed that planning comprised three components: (a) Planning for Child Care, (b) Planning With Partner, and (c) Planning With Employer. Work satisfaction, hours worked before commencing maternity leave, anticipated weeks of maternity leave and anticipated hours per week on returning to work were consistent cross-sectional predictors of the three components of planning. Additionally, support from family and social groups was associated with the Planning With Partner component, and support from the workplace was associated with the Planning With Employer component. Unfortunately, given the cross-sectional nature of that study, women were not tracked into the postpartum period to investigate the impact of planning and other factors on their return to work after maternity leave. The study reported here addresses this limitation.

Other studies that have examined the employment outcomes of women following childbirth also have had methodological limitations. Often the studies were carried out retrospectively (e.g., Baxter, 2009; Cortese, 2001; Feldman, Masalha, & Nadam, 2001; Feldman, Sussman, & Zigler, 2004), included only mothers of first-born children (e.g., Feldman et al., 2001; Feldman et al., 2004; Harrison & Ungerer, 2002), or excluded potential participants who may have experienced ill health following birth (e.g., Feldman et al., 2001; Feldman et al., 2004). Studies often also either included women who did not intend to return to work after childbirth (e.g., Harrison & Ungerer, 2002; Houston & Marks, 2003; Hyde, Klein, Essex, & Clark, 1995; Klein, Hyde, Essex, & Clark, 1998), or only involved women who had already returned to work (e.g., Feldman et al., 2001; Feldman et al., 2004). Finally, a few studies have examined any active role that women may have played in their return to work, such as planning for their return to work (e.g., Harrison & Ungerer, 2002; Houston & Marks, 2003).

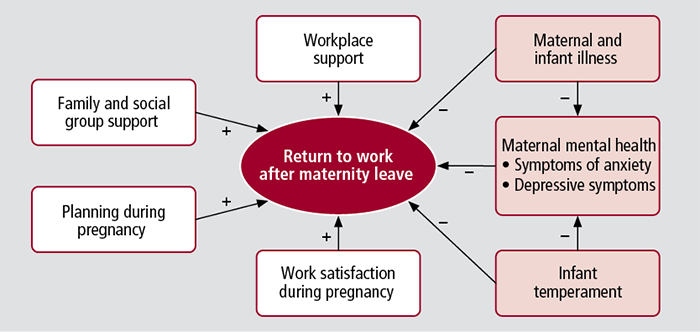

The aim in the current study was to examine various factors that contribute to returning to work after childbirth for women who, during pregnancy, expressed their intention to return to work by the time their child had reached 12 months of age. These factors stem from sources both internal to women, such as maternal psychopathology and maternal illness, and external to women, such as infant temperament and support from family and social groups. Additionally, factors that may contribute to women's return to work after maternity leave may occur during pregnancy, and/or in the postpartum period. Thus, in the current study, only women who were pregnant and had reported that they intended to return to work at some point in the first 12 months of their child's life were recruited to participate in the study. Considering the diverse nature of factors that may influence whether or not women return to work after having a child, we adopted a multifactorial perspective, taking into account several factors that have been linked in the literature to maternal employment and women's return to work after maternity leave. Figure 1 illustrates the factors that we proposed would predict whether or not women returned to work after maternity leave.

Figure 1: A model of factors proposed to predict women's return to work after maternity leave

Note: A plus sign (+) suggests a positive association, and a minus sign (-) suggests a negative association between the respective variable and returning to work.

Several factors have been directly associated with women's return to work after maternity leave. The amount of planning completed during pregnancy by women for their later return to work has not been widely explored in the literature. A few key studies (Harrison & Ungerer, 2002; Houston & Marks, 2005) have demonstrated that greater amounts of planning predict whether women will return to work, and whether they will return to work as they had intended.

Satisfaction with work and the workplace is an important factor in the retention of employees in a variety of work settings (De Milt, Fitzpatrick, & McNulty, 2011; Delobelle et al., 2011; Jones, Kantak, Futrell, & Johnston, 1996; Smith, Gregory, & Cannon, 1996; Stockard & Lehman, 2004) and has been shown to be of particular importance to parents (Brough, O'Driscoll, & Biggs, 2009). Another work-related variable that has been linked to the return to work after maternity leave is support from the workplace. Studies by Glass and Riley (1998) and Houston and Marks (2003) found that women were more likely to return to work if they perceived that they had support from their employers and colleagues. Other research has shown that workplace support is beneficial for employees returning to work following illness or injury (Lysaght & Larmour-Trode, 2008). Support from family and social groups has also been implicated in whether women return to work after the birth of their children (Harrison & Ungerer, 2002).

In addition, several maternal and child-related factors have been established as predictors of return to work after maternity leave. The child's temperament (Feldman et al., 2001; Galambos & Lerner, 1987) and maternal and infant illness (Spiess & Dunkelberg, 2009), particularly in the first year postpartum, are linked to maternal employment. Financial considerations have also been shown to influence women's return to work after maternity leave. Baxter (2008) found that one-third of women who returned to work after maternity leave had cited "I/we needed the money" as being the sole reason for their return, with an additional one-third citing this reason along with other reasons, such as needing to maintain skills/qualifications. Women who had higher personal incomes were also more likely to return to work after maternity leave than those with lower personal incomes (Houston & Marks, 2003).

Maternal mental health - specifically heightened depressive and anxiety symptoms - and its relationship with employment status has been the focus of several studies (Brooks-Gunn, Han, & Waldfogel, 2010; des Rivières-Pigeon, Séguin, Goulet, & Descarries, 2001; Feldman et al., 2001; Hyde, Else-Quest, Goldsmith, & Biesanz, 2004; McBride & Belsky, 1988; Rout et al., 1997; Spiess & Dunkelberg, 2009). However, the direction of the relationship between maternal mental health and employment status is often unclear; it remains to be clarified whether employment leads to good mental health for women or whether good mental health leads to employment.

In addition to their direct relationship with returning to work after maternity leave, maternal and infant illness and infant temperament have also been shown to affect maternal mental health (Gjerdingen & Chaloner, 1994; Harrison & Ungerer, 2002; Hyde et al., 2004; Hyde et al., 1995; Klein et al., 1998; Marshall & Tracy, 2009; Spiess & Dunkelberg, 2009).

Accordingly, we developed two hypotheses (see Figure 1). Firstly, we hypothesised that fewer maternal or infant illnesses during pregnancy and up to four months postpartum and having a child with a more easygoing temperament (as opposed to a more difficult temperament) would predict lower levels of maternal psychopathology later on in the postpartum period. We also hypothesised that these lower levels of postpartum maternal psychopathology, along with increased work satisfaction during pregnancy, greater postpartum support from family and social groups, greater postpartum support from the workplace, and greater amounts of planning during pregnancy for the return to work would predict returning to work after maternity leave.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 186 Australian women who volunteered during their pregnancy to participate, and who stated that they intended to return to work within the first 12 months postpartum. Of this total sample, 155 women returned to work (RTW) and 31 women did not return to work (DNRTW). A further 32 women agreed to participate in the study; however, they either did not return any of the questionnaires mailed to them (n = 19), or returned only some of the questionnaires.1 Participants were recruited from a variety of sources, such as emails sent via mailing lists (43.5%, n = 81); advertisements placed in parenting magazines and websites (12.4%, n = 23) and local newspapers (11.3%, n = 21); and flyers handed out at parenting information exhibitions (9.7%, n = 18). Table 1 contains the participants' demographic information across the two groups, RTW and DNRTW. The majority of participants were employed in high status occupations and had high education levels; however, due to participants self-selecting to participate in the study, we were unable to control for this.

| All participants (N = 186) | RTW (N = 155) | DNRTW (N = 31) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 32.71 (3.99) | 32.99 (3.79) | 31.32 (4.66) |

| Gestation (weeks) | 32.67 (4.01) | 32.65 (4.00) | 32.77 (4.13) |

| Time employed by current employer (years) | 4.5 (3.57) | 4.71 (3.64) | 3.47 (3.04) |

| Hours worked before commencing maternity leave | 37.16 (8.56) | 37.34 (8.60) | 36.26 (8.45) |

| Anticipated length of maternity leave (weeks) | 36.79 (14.41) | 34.94 (14.27) | 45.81 (11.55) ** |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Expecting first child | 133 (71.5%) | 110 (71.0%) | 23 (74.2%) |

| Married or in de facto relationship | 184 (98.9%) | 154 (99.4%) | 30 (96.8%) |

| English is main language b | 158 (98.8%) | 130 (98.5%) | 28 (100.0%) |

| Born in Australia b | 127 (79.4%) | 104 (78.8%) | 23 (82.1%) |

| Family income over A$100,000 per year b | 100 (54.3%) | 90 (58.8%) ** | 10 (32.3%) |

| Completed at least undergraduate university qualification b | 117 (63.6%) | 105 (67.7%) | 12 (41.4%) * |

| Working in a "professional" or "manager and administrator" position b | 121 (66.1%) | 103 (67.8%) | 18 (58.1%) * |

| Worked 30 hours per week or more before commencing maternity leave b | 154 (84.2%) | 128 (84.2%) | 11 (83.9%) |

Note: RTW = returned to work. DNRTW = did not return to work. a All data were collected at Time 1 except for gestation data. b Percentages may vary due to participant non-response. * p < .05, ** p < .01.

Measures

Participants were mailed questionnaires containing different measures, at three time points:

- Time 1 (T1), sent in participants' third trimester of pregnancy, which included measures relating to:

- demographics;

- planning for return to work;

- work satisfaction;

- anticipated support from family and social groups;

- anticipated support from the workplace;

- depressive symptoms; and

- symptoms of anxiety;

- Time 2 (T2), sent at four months postpartum, which measured:

- maternal and infant illness during pregnancy and postpartum; and

- infant temperament; and

- Time 3 (T3), sent six weeks after the return to work for participants who did return to work, and at 13 months postpartum for those who did not return to work, which measured:

- support received from family and social groups;

- support received from the workplace;

- depressive symptoms; and

- symptoms of anxiety.2

Demographic and other information

At T1, participants reported their age, ethnicity, marital status, annual family income, number of children the mother already had (parity), length of gestation, education level, details of current employment (such as years of employment with current employer, position, and hours worked per week), anticipated length of maternity leave, and anticipated number of hours to be worked after their return to work following maternity leave.

Planning during pregnancy for the return to work

A questionnaire to measure the amount of planning done by participants during pregnancy for the return to work was developed for this study, as described in Coulson et al. (2010). The questionnaire contained eight items that the women could complete during pregnancy relating to planning for their return to work, such as "I have talked to my partner about when I would like to return to work after maternity leave, and how many hours and days I would like to work" and "I have organised who would care for our child while I am at work (e.g., my partner, a babysitter)". Participants rated the items as 0 = "No, not at all"; 1= "Did some of, or kind of did this", and 2 = "Yes, did this completely", with a higher score indicating that the participant had completed a greater amount of planning during her pregnancy for the return to work.3

Work satisfaction

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire - Short Form (MSQ; Weiss, Dawis, England, & Lofquist, 1967) was used to measure participant work satisfaction. The MSQ is a commonly used measure of work satisfaction, and considered to be one of the most valid and reliable (Ozyurt, Hayran, & Sur, 2006; VanVoorhis & Levinson, 2005; Welbourne, Eggerth, Hartley, Andrew, & Sanchez, 2007). The 20-item scale covers various facets of an employee's satisfaction with their job, and requires responses to be given on a scale from 1 ("very dissatisfied") to 5 ("very satisfied").

Support from family and social groups and the workplace

Participants were asked about the amount of support that they anticipated they would receive after the birth (T1) and the amount of support they had received since the birth of their child (T3). Support was defined as coming from two key sources: (a) their family and social groups (partner, parents and in-laws, and other family and friends), and (b) their workplace (employer and colleagues). Support addressed two separate functions: (a) physical support (e.g., help with household chores, flexibility with shifts), and (b) emotional support (e.g., listening to concerns, being there for the participant).

For T1, these items were identical to those used by Coulson et al. (2010); for T3 the items were essentially the same except that they focused on the amount of support the participant perceived they had received from these sources, rather than what the participant anticipated they would receive. Both questionnaires comprised ten items, with one item regarding physical support and one regarding emotional support for each support source. A higher score indicated a greater amount of support had been received.

Depressive symptoms

To assess their depressive symptoms, participants were administered the Edinburgh Post Natal Depression (EPND) scale, which relates to depressive symptoms experienced in the past seven days (Cox, 1994; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). The EPND scale was selected for use in this study as it was suitable for use in both the pregnancy and postpartum periods (Cox, 1994). The version of the EPND scale given to participants contained nine items rather than ten, as the question regarding self-harm was excluded for university ethics purposes.

Symptoms of anxiety

Participants' level of anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, 1983). Only the Trait Anxiety subscale was included in the analyses, as the items in that subscale asked the participant how they had been feeling over the last seven days. This provided a more consistent measure of anxiety than the State Anxiety subscale items, which focused on how the respondent felt at that current point in time. The Trait subscale of the STAI contains 20 items, which are scored on a scale from 1 ("not at all") to 4 ("very much so").

Maternal and infant illness during pregnancy and postpartum

The details of any illnesses or complications experienced by participants and their infants during the pregnancy and/or postpartum periods were ascertained by an open-ended question. Participants were free to write as much or as little detail as they felt necessary. These answers were then coded into the different types of illnesses or complications experienced (e.g., gestational diabetes, emergency caesarean section, child's severe reflux), with each participant scoring 1 if they had experienced this problem, or 0 if they had not. These scores were then totalled to compute a maternal and child illness score.

Infant temperament

Participants were administered the Short Infant Temperament Questionnaire (SITQ; Sanson, Prior, Garino, Oberklaid, & Sewell, 1987) to assess infant temperament at T2. The SITQ is a 30-item scale that addresses infant temperament on five subscales: Approach, Cooperation-Manageability, Rhythmicity, Activity-Reactivity, and Irritability. However, for the purposes of this study, only the total scale score was analysed. Responses are given on a Likert scale from 1 ("almost never") to 5 ("almost always"), with a higher score indicating that the infant has a more difficult temperament. Initial inspection of the scale scores showed that many participants had not answered one particular item of the SITQ (question 27: "My child is irritable or moody throughout a cold or stomach virus"), citing that their child had not yet experienced either of these illnesses. Accordingly, this item was removed, with the remaining 29 items used in the analyses.

Procedure

Following ethics approval, pregnant women were recruited from the stated sources. The advertisements invited pregnant women to participate in a study regarding the transition back to work after maternity leave, and those who were interested in participating were asked to contact the researchers by telephone or email. Screening of prospective participants ensured that only women who were currently pregnant and who intended to return to work within the first 12 months postpartum were recruited to the study. Participants were recruited at any stage during their pregnancy; however, the T1 questionnaire package was only sent to participants for completion during the third trimester of pregnancy to ensure that they had sufficient opportunity to consider issues such as returning to work, sources of support and child care. Participants received three questionnaire packages, at various points during their pregnancy and the postpartum period. The timing of the questionnaire packages and the measures contained within them is outlined in the section on Measures.

When each participant reached the appropriate time point, they were mailed the questionnaire pack, with a Reply Paid envelope to return their completed questionnaire. To ensure that participants received the T3 questionnaire package at the appropriate time, they were contacted by telephone approximately six weeks prior to their nominated return-to-work date (as nominated by them in the T1 questionnaire) to confirm whether they were actually returning to work on that date, had arranged to return at a later date, or were no longer planning to return to work by the time their child was 12 months old. Participants in the RTW group completed the T3 questionnaires approximately six weeks after their return to work, and those in the DNRTW group completed these at approximately 13 months postpartum. Participants were naïve to the specific hypotheses of the overall study, although they were informed of the general nature of the study.

Analyses

A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses and a logistic regression analysis were performed to assess the impact of the measured variables on the return-to-work outcome. Specific details regarding the analyses are available from the authors.

Results

Analyses of demographic variables

The scores for the RTW and DNRTW groups were compared on several demographic factors (see Table 1). Significant differences were found between the two groups in relation to the anticipated length of maternity leave, education level, occupation classification, and annual family income (see Table 1). There were no other significant differences found between the groups.

Predictors of maternal mental health at T3

Maternal and child illness, and infant temperament were not significant predictors of anxiety or depressive symptoms at T3.4

Predictors of return to work after maternity leave

The data for ten participants (eight in the RTW group and two in the DNRTW group) were not included in the analysis as they were missing demographic information, and logistic regression requires that all cases have complete data. The variables were analysed in two stages (see Appendix Table A1): the first stage included the T1 variables, to account for any impact these may have had on the measures repeated at T3; the second stage included all the variables. At Step 1, the model did not significantly predict the return to work outcome, with none of the variables being significant predictors. At Step 2, the model was able to significantly differentiate between those who did return to work, and those who did not. The model was able to correctly classify 97.3% (n = 143) of the RTW cases and 89.7% (n = 26) of DNRTW cases.

Five of the variables were found to be significant predictors of women's return to work after maternity leave. Of these, infant temperament was the strongest predictor of RTW, with an odds ratio of 101.3, indicating that participants who reported that their child had a more difficult temperament were 101.3 times more likely to return to work. Planning during pregnancy (OR = 1.79), workplace support at T3 (OR = 1.57), depressive symptoms at T3 (OR = .80) and anticipated length of maternity leave (OR = .86) were also significant predictors of RTW, indicating that participants who planned more during pregnancy, reported that they had perceived greater support from their workplace since the birth of their child, reported fewer depressive symptoms and had anticipated that they would take a shorter maternity leave were more likely to return to work.

Discussion

The results from this study indicate that factors relating to the women, their children, and external sources predict whether or not mothers return to work following childbirth. The findings support the notion that women's return to work after childbirth must be viewed from a multifactorial perspective, due to the varied sources of influence. Interestingly, the strongest predictor of returning to work after maternity leave was infant temperament, with participants who reported that their child had a more difficult temperament being more likely to return to work. Although it was not explored in the current study, it is possible that mothers of children perceived as having a more difficult temperament (having characteristics such as being uncooperative, having inconsistent sleeping patterns, and being difficult to soothe when upset) may have found it easier to return to work as a break from the child's behaviour and demands. Conversely, Feldman et al. (2001) found that a more easy infant temperament was associated with returning to work after maternity leave, as did Galambos and Lerner (1987). These researchers postulated that the children's easy-going temperaments may have enabled the mothers to return to work, as they would be easier to leave in the care of others. Due to the inconsistency in these findings, and the lack of investigation in this area, further research is warranted to determine whether the current finding is robust, and the reasons behind it.

Consistent with the findings of Houston and Marks (2003), the current study also found that the amount of planning for the return to work undertaken during pregnancy differentiated women who returned to work from those who did not. We found that the amount of support received from the workplace since the birth of the child predicted whether or not women would return to work, which differed from Houston and Marks' finding that workplace support only predicted whether women who returned to work did so for the time fraction (either part-time or full-time) that they had intended when pregnant. The level of depressive symptoms also predicted return to work; women who had higher levels of depressive symptoms were less likely to return to work at the time they had intended to do so during pregnancy. A further interesting finding was that the anticipated length of maternity leave reported during pregnancy predicted return to work, with women who reported that they anticipated taking a shorter maternity leave being more likely to return to work as they had intended.

The current findings provide support for the theory of self-regulation of goal attainment (Bagozzi, 1992), which proposes that for behaviours where there is a substantial delay in time from the initial intention to the goal, the simple act of intending to perform the behaviour is unlikely to be a strong predictor of the behaviour actually occurring. For such behaviours, termed "future-oriented intentions", Bagozzi argued that to accomplish the intended goal, three elements must intervene between the initial intention and the completion of the goal: instrumental acts, motivational processes, and facilitating/ inhibiting factors. In this case, instrumental acts (e.g., planning during pregnancy, anticipated length of maternity leave) and facilitating/inhibiting conditions (e.g., infant temperament, workplace support, depressive symptoms) have been shown to affect whether women's intentions to return to work after maternity leave are actually accomplished. The results of this study suggest that a systematic and rigorous evaluation of this theory may be worthwhile to progress our understanding of what factors contribute to a positive return to work for women after maternity leave.

Limitations

The current study found that annual family income was not a predictor of returning to work after maternity leave, despite significant differences being found between the women who did and did not return to work and previous studies finding that both personal (Houston & Marks, 2003) and family income have been positively associated with returning to work (Callender, Millward, Lissenburgh, & Forth, 1997; Desai & Waite, 1991; Klerman & Leibowitz, 1994). Only family income and not personal income was measured in the current study; it would be advisable for future research to measure both aspects of income. A factor related to this is that in the current study, most participants were highly educated, were mainly employed in professional or managerial positions, and therefore had relatively high family incomes. As such, many of the participants were from a higher socio-economic background. Future research should seek to replicate the current study with participants from a wider socio-economic range. Additionally, our study had a small sample size; replication with a larger sample size is desirable.

Practical implications

This study has indicated several ways in which women who wish to return to work after the birth of a child may be facilitated to do so. Workplaces - both employers and colleagues - can ensure that women feel, and are, supported before and during their maternity leave. Support must come in the form of both physical support, such as being flexible with work starting times, and emotional support, such as listening to the women's concerns. This may be achieved by negotiating the needs of both the women and the organisations in regard to work times and places, and ensuring that women feel "in the loop" and cared for, even when on maternity leave. Employers should seek to make all employees aware that women who are about to take or are on maternity leave should feel that they have the support of their colleagues, and that this is important for the organisation. Workplaces can also positively affect the amount of planning that women complete during pregnancy for their return to work. Organisations should ensure that human resource managers and direct line managers encourage women to make plans for their return to work before commencing maternity leave. They should also highlight to women that the scope of the planning arrangements needs to cover multiple facets - the workplace, the child's father, and child care (Coulson et al., 2010). This may be particularly pertinent for women who propose taking a longer amount of leave, as employers can provide further support and guidance to help these women return to work.

As proposed by Coulson et al., employers could develop a return-to-work program in which women and their managers can participate before maternity leave has commenced. Such a program could ensure that appropriate protocols are followed, and that women receive information that is consistent and relevant, and could potentially continue until after the women have returned to work. It is interesting to note that a literature search uncovered several papers regarding the development, implementation and benefits of return-to-work programs for employees with illnesses, injuries or disabilities (e.g., Lysaght & Larmour-Trode, 2008; Payne, 2011; Tjulin, Edvardsson Stiwne, & Ekberg, 2009). No such literature was found on return-to-work programs for pregnant women.

Additionally, other programs could also encourage women to plan for their return to work after maternity leave. For example, in Australia, during the period of prenatal care, many women receive the "Bounty Mother to Be Bag" (ACP Magazines, 2011; Nichols, Nixon, & Rowsell, 2009), which is distributed free to pregnant women via their midwife or hospital, and contains information and product samples. Information highlighting the importance for planning for the return to work after maternity leave, and ways in which women could complete this, could be included with the other information provided in such bags. Additionally, information regarding planning for the return to work could also be included in other resources for mothers-to-be, such as pregnancy magazines, or on pregnancy and parenting websites.

The recognition of women's levels of depressive symptoms is vital - not just for the return to work, but also for their own health and that of their child. In terms of women's return to work after maternity leave, only postpartum depressive symptoms were found to predict whether or not women would return to work. Thus, depressive symptoms could be monitored through multiple avenues, such as maternal and child health nurses, family doctors, and workplaces. These resources could also highlight the importance of good mental health to new mothers, and provide them with information on further services if they are required.

Endnotes

1 Completed Time 1 only: n = 5. Completed Time 1 and Time 2 only: n = 8. For time points in the study, see the section on Measures.

2 Time 1: M = 32.67 weeks gestation, SD = 4.01. Time 2: RTW, M = 15.61 weeks postpartum, SD = 2.88; DNRTW, M = 16.57 weeks postpartum, SD = 5.04. Time 3: RTW, M = 40.82 weeks postpartum, SD = 15.35; DNRTW, M = 70.20 weeks postpartum, SD = 13.3.

3 The Cronbach alphas for the majority of the measures used was above .70, indicating at least good internal consistency. Details of these analyses are available from the authors.

4 Details of these analyses are available from the authors.

References

- ACP Magazines (2011). Bounty Mother to Be Bag. Sydney: ACP Magazines. Retrieved from <www.acp.com.au/bounty_mother_to_be_bag.htm>.

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 178-204.

- Baxter, J. (2005). Women's work transitions around childbearing. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Baxter, J. (2008). Is money the main reason mothers return to work after childbearing? Journal of Population Research, 25(2), 141-160.

- Baxter, J. (2009). Mothers' timing of return to work by leave use and pre-birth job characteristics. Journal of Family Studies, 15(2), 153-166.

- Bernthal, P. R., & Wellins, R. S. (2001). Retaining talent: A benchmarking study. Pittsburgh, PA: HR Benchmark Group.

- Bianchi, S. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2010). Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 705-725.

- Brooks-Gunn, J., Han, W.-J., & Waldfogel, J. (2010). What distinguishes women who work full-time, part-time, or not at all in the 1st year? Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 75(2), 35-49.

- Brough, P., O'Driscoll, M., & Biggs, A. (2009). Parental leave and work-family balance among employed parents following childbirth: an exploratory investigation in Australia and New Zealand. K?tuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 4, 71-87.

- Callender, C., Millward, N., Lissenburgh, S., & Forth, J. (1997). Maternity rights and benefits in Britain 1996 (Department of Social Security Research Report No. 67). London: The Stationery Office.

- Cortese, D. (2001). Factors influencing the return to work from maternity leave of Victorian Registered Nurses. Bundoora, Vic.: La Trobe University.

- Coulson, M., Skouteris, H., Milgrom, J., Noblet, A., & Dissanayake, C. (2010). Factors influencing the planning undertaken by women during pregnancy for their return to work after maternity leave. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Organisational Psychology, 3, 1-12.

- Cox, J. (1994). Origins and development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. In J. Cox & J. Holden (Eds.), Perinatal psychiatry: Use and misuse of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. London: Gaskell.

- Cox, J., Holden, J., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782-786.

- Davidson, M. C. G., Timo, N., & Wang, Y. (2010). How much does labour turnover cost? A case study of Australian four- and five-star hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(4), 451-466.

- De Milt, D. G., Fitzpatrick, J. J., & McNulty, S. R. (2011). Nurse practitioners' job satisfaction and intent to leave current positions, the nursing profession, and the nurse practitioner role as a direct care provider. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 23(1), 42-50.

- Delobelle, P., Rawlinson, J. L., Ntuli, S., Malatsi, I., Decock, R., & Depoorter, A. M. (2011). Job satisfaction and turnover intent of primary healthcare nurses in rural South Africa: A questionnaire survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(2), 371-383.

- des Rivières-Pigeon, C., Séguin, L., Goulet, L., & Descarries, F. (2001). Unravelling the complexities of the relationship between employment status and postpartum depressive symptomatology. Women and Health, 34(2), 61-79.

- Desai, S., & Waite, L. J. (1991). Women employment during pregnancy and after the 1st birth: Occupational characteristics and work commitment. American Sociological Review, 56(4), 551-566.

- Feldman, R., Masalha, S., & Nadam, R. (2001). Cultural perspective on work and family: Dual-earner Israeli-Jewish and Arab families at the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(3), 492-509.

- Feldman, R., Sussman, A., & Zigler, E. (2004). Parental leave and work adaptation at the transition to parenthood: Individual, marital, and social correlates. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(3), 459-479.

- Galambos, N. L., & Lerner, J. V. (1987). Child characteristics and the employment of mothers with young children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(1), 87-98.

- Gjerdingen, D., & Chaloner, K. (1994). The relationship of women's postpartum mental health to employment, childbirth, and social support. Journal of Family Practice, 38(5), 465-472.

- Gjerdingen, D., McGovern, P., Bekker, M., Lundberg, U., & Willemsen, T. (2001). Women's work roles and their impact on health, well-being, and career: Comparisons between the United States, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Women and Health, 31(4), 1-20.

- Glass, J., & Riley, L. (1998). Family responsive policies and employee retention following childbirth. Social Forces, 76(4), 1401-1435.

- Gottfried, A. E., & Gottfried, A. W. (2008). The upside of maternal and dual-earner employment: A focus on positive family adaptations, home environments, and child development in the Fullerton Longitudinal Study. In A. Marcus-Newhall, D. Halpern & S. Tan (Eds.), The changing realities of work and family (pp. 25-42). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Harrison, L. J., & Ungerer, J. A. (2002). Maternal employment and infant-mother attachment security at 12 months postpartum. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 758-773.

- Houston, D., & Marks, G. (2003). The role of planning and workplace support in returning to work after maternity leave. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 41(2), 197-214.

- Houston, D., & Marks, G. (2005). Working, caring and sharing: Work-life dilemmas in early motherhood. In D. Houston (Ed.), Work life balance in the twenty-first century. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hyde, J. S., Else-Quest, N. M., Goldsmith, H. H., & Biesanz, J. C. (2004). Children's temperament and behavior problems predict their employed mothers' work functioning. Child Development, 75(2), 580-594.

- Hyde, J. S., Klein, M., Essex, M., & Clark, R. (1995). Maternity leave and women's mental health. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19(2), 257-285.

- Jones, E., Kantak, D. M., Futrell, C. M., & Johnston, M. W. (1996). Leader behavior, work-attitudes, and turnover of sales people: An integrative study. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 16(2), 13-23.

- Klein, M., Hyde, J. S., Essex, M., & Clark, R. (1998). Maternity leave, role quality, work involvement, and mental health one year after delivery. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22(2), 239-266.

- Klerman, J. A., & Leibowitz, A. (1994). The work-employment distinction among new mothers. Journal of Human Resources, 29(2), 277-303.

- Lee, C., & Powers, J. R. (2002). Number of social roles, health, and well-being in three generations of Australian women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 9(3), 195-215.

- Lysaght, R. M., & Larmour-Trode, S. (2008). An exploration of social support as a factor in the return-to-work process. Work, 30(3), 255-266.

- Marshall, N. L., & Tracy, A. J. (2009). After the baby: Work-family conflict and working mothers' psychological health. Family Relations, 58(4), 380-391.

- McBride, S., & Belsky, J. (1988). Characteristics, determinants, and consequences of maternal separation anxiety. Developmental Psychology, 24(3), 407-414.

- Nichols, S., Nixon, H., & Rowsell, J. (2009). The "good" parent in relation to early childhood literacy: Symbolic terrain and lived practice. Literacy, 43(2), 65-74.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2007). Babies and bosses: Reconciling work and family life: A synthesis of findings for OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Ozyurt, A., Hayran, O., & Sur, H. (2006). Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish physicians. Qjm: An International Journal of Medicine, 99(3), 161-169.

- Payne, A. (2011). Rehabilitation provides route to recovery. Occupational Health, 63(3), 12.

- Phillips, J. D. (1990). The price tag on turnover. Personnel Journal, 69(12), 58-61.

- Rout, U., Cooper, C., & Kerslake, H. (1997). Working and non-working mothers: A comparative study. Women in Management Review, 12(7), 264-275.

- Sanson, A., Prior, M., Garino, E., Oberklaid, F., & Sewell, J. (1987). The structure of infant temperament: Factor analysis of the Revised Infant Temperament Questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development, 10, 97-104.

- Schnittker, J. (2007). Working more and feeling better: Women's health, employment, and family life, 1974-2004. American Sociological Review, 72(2), 221-238.

- Scholss, E. P., Flanagan, D. M., Culler, C. L., & Wright, A. L. (2009). Some hidden costs of faculty turnover in clinical departments in one academic medical center. Academic Medicine, 84(1), 32-36.

- Skouteris, H., McNaught, S., & Dissanayake, C. (2007). Mothers' transition back to work and infants' transition to child care: Does work-based child care make a difference? Child Care in Practice, 13(1), 33-47.

- Smith, K., Gregory, S., & Cannon, D. (1996). Becoming an employer of choice: Assessing commitment in the hospitality workplace. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 8(6), 3-9.

- Spielberger, C. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Spiess, C. K., & Dunkelberg, A. (2009). The impact of child and maternal health indicators on female labour force participation after childbirth: Evidence for Germany. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 40(1), 119-138.

- Stockard, J., & Lehman, M. B. (2004). Influences on the satisfaction and retention of 1st-year teachers: The importance of effective school management. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(5), 742-771.

- Tan, S. J. (2008). The myths and realities of maternal employment. In A. Marcus-Newhall, D. Halpern & S. Tan (Eds.), The changing realities of work and family (pp. 9-24). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Tjulin, Å., Edvardsson Stiwne, E., & Ekberg, K. (2009). Experience of the implementation of a multi-stakeholder return-to-work programme. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 19(4), 409-418.

- Tracey, J. B., & Hinkin, T. R. (2008). Contextual factors and cost profiles associated with employee turnover. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 49(1), 12-27.

- VanVoorhis, R. W., & Levinson, E. M. (2005). Job satisfaction among school psychologists: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 21(1), 77-90.

- Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V., England, G. W., & Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Industrial Relation Center.

- Welbourne, J. L., Eggerth, D., Hartley, T. A., Andrew, M. E., & Sanchez, F. (2007). Coping strategies in the workplace: Relationships with attributional style and job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(2), 312-325.

Appendix

| Coefficient | Odds ratio | 95% CI for odds ratio Lower | 95% CI for odds ratio Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 a | ||||

| Anticipated support from family and social groups | −.05 | .95 | .85 | 1.07 |

| Anticipated support from the workplace | .07 | 1.07 | .95 | 1.19 |

| Depressive symptoms at T1 | −.13 | .88 | .77 | 1.01 |

| Symptoms of anxiety at T1 | .03 | 1.03 | .96 | 1.10 |

| Step 2 b | ||||

| Anticipated support form family and social groups | .13 | 1.13 | .85 | 1.51 |

| Anticipated support from the workplace | −.39 | .68 | .44 | 1.04 |

| Depressive symptoms at T1 | .18 | 1.20 | .85 | 1.68 |

| Symptoms of anxiety at T1 | .07 | 1.07 | .93 | 1.23 |

| Planning during pregnancy | .58 | 1.79 * | 1.02 | 3.16 |

| Support received from family and social groups | .03 | 1.03 | .86 | 1.24 |

| Support received from the workplace | .45 | 1.57 ** | 1.19 | 2.07 |

| Depressive symptoms at T3 | −.23 | .80 * | .64 | .99 |

| Job satisfaction | −.03 | .98 | .87 | 1.10 |

| Maternal and infant illness | −.45 | .64 | .32 | 1.28 |

| Infant temperament | 4.62 | 101.30 * | 2.86 | 3588.13 |

| Anticipated length of maternity leave | −.15 | .86 * | .76 | .97 |

| Maternal education (ref. = Less than Year 12) | ||||

| Year 12 | −27.90 | .00 | - | - |

| TAFE/post-Year 12 training course | −25.39 | .00 | - | - |

| Undergraduate university degree | −24.33 | .00 | - | - |

| Postgraduate university degree | −25.03 | .00 | - | - |

| Family income (ref. = $20,000 to $39,999) | ||||

| $40,000 to $59,999 | 24.36 | 3.81E10 | - | - |

| $60,000 to $79,999 | 26.68 | 3.87E11 | - | - |

| $80,000 to $99,999 | 24.33 | 3.70E10 | - | - |

| $100,000 and over | 25.94 | 1.85E11 | - | - |

| Occupation classification (ref. = Elementary clerical, sales and service) | ||||

| Intermediate clerical, sales and service | −28.76 | .00 | - | - |

| Advanced clerical and service | −18.53 | .00 | - | - |

| Tradespersons and related | −9.82 | .00 | - | - |

| Associate professionals | 1.50 | 4.47 | - | - |

| Professionals | −19.94 | .00 | - | - |

| Managers and administrators | −18.26 | .00 | - | - |

Note: CI = confidence interval. a χ 2 (4, N = 176) = 5.29, p = .26. b χ 2 (26, N = 176) = 113.73, p < .001. * p < .05, ** p < .01.

Coulson, M., Skouteris, H., & Dissanayake, C. (2012). The role of planning, support, and maternal and infant factors in women's return to work after maternity leave. Family Matters, 90, 33-44.