The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program

An example of a public health approach to evidence-based parenting support

June 2015

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Using the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a case study, this article discusses how to design and disseminate a system of parenting support within a public health framework in Australia. It describes the importance of public health programs, the design and rationale of Triple P, the evaluation evidence supporting Triple P, how a public health approach to parenting support works, and the reliable measurement of population-level effects.

Why parenting programs are so important

The quality of parenting that children receive has a major influence on their development, wellbeing and life opportunities (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002; Griffin, Botvin, Scheier, Diaz, & Miller, 2000). Parenting programs that seek to improve parenting practices while simultaneously enhancing child development are vital to establishing a nurturing environment that acts to offset the development of behavioural and psychological problems and lays the foundation for children to contribute to a healthy and functional society (Biglan, Flay, Embry, & Sandler, 2012). There is now broad scientific and interdisciplinary consensus that behaviourally oriented active skills training programs that teach parents positive parenting and contingency management skills are effective. Such programs have transformed child and family-focused mental health support and prevention services (Comer, Chow, Chan, Cooper-Vince, & Wilson, 2013; McCart, Priester, Davies, & Azen, 2006; Menting, de Castro, & Matthys, 2013).

Parenting programs are potentially powerful tools in the prevention and treatment of a range of child social, emotional and behavioural problems including challenging behaviour in children with developmental disabilities (Tellegen & Sanders, 2014; Whittingham, Sanders, McKinlay, & Boyd, 2014), persistent feeding problems (Adamson, Morawska, & Sanders, 2013), anxiety disorders (Rapee, Kennedy, Ingram, Edwards, & Sweeney, 2010), recurrent pain syndromes (Sanders, Cleghorn, Shepherd, & Patrick, 1996), and childhood obesity (West, Sanders, Cleghorn, & Davies, 2010). Positive intervention effects on child and parent outcome measures have been reported across diverse cultures (e.g., Mejia, Calam, & Sanders, 2014; Turner, Richards, & Sanders, 2007), family types (e.g., Stallman & Sanders, 2007), stages of child development (e.g., Salari, Ralph, & Sanders, 2014), and delivery settings (e.g., Morawska et al., 2011). Positive intervention effects have been found to be maintained over time (e.g., Heinrichs, Kliem, & Hahlweg, 2014) without the need for further booster sessions.

Recent research has also demonstrated how different parenting styles and strategies influence various aspects of brain development. One study showed how harsh parenting reduces telomere length in the brain (a biomarker for chronic stress; Mitchell et al., 2014); while another by Luby et al. (2013) demonstrated how even in environments of poverty, altering the ways children are raised can help alleviate some of the adverse effects of disadvantage and promote healthy brain development in children.

Available evidence about maltreating parents suggests that parent training leads to improvements in parenting competence and parent behaviour (Holzer, Higgins, Bromfield, & Higgins, 2006; Sanders & Pidgeon, 2010). These changes in parenting practice reduce the risks of further abusive behaviour towards children, referrals to protective agencies and visits to hospital. Beyond younger children, potentially modifiable parenting and family risk factors can also be targeted to reduce the rates of emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents (Dekovic, Janssens, & Van As, 2003).

Although studies on parenting programs for parents of teenagers are less extensive compared to studies with younger children (Kazdin, 2005), programs have been demonstrated to improve parent-adolescent communication and reduce family conflict (Barkley, Edwards, Laneri, Fletcher, & Metevia, 2001; Chu et al., 2013; Dishion & Andrews, 1995), and reduce the risk of adolescents developing and maintaining substance abuse, delinquent behaviour and other externalising problems (Connell, Dishion, Yasui, & Kavanagh, 2007; Mason, Kosterman, Hawkins, Haggerty, & Spoth, 2003). Parents of adolescents who have participated in parenting programs have reported higher levels of confidence and use of more effective parenting strategies (Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 1998).

Traditional approaches to parent training involve working with individual families or small groups of parents; although effective, such programs reach relatively few parents and consequently are unlikely to reduce rates of serious child-development problems related to inadequate parenting (Prinz & Sanders, 2007). In a household telephone survey of 4,010 Australian parents with a child under the age of 12 years, 75% of respondents who had a child with an emotional or behavioural problem had not participated in a parenting program (Sanders, Markie-Dadds, Rinaldis, Firman, & Baig, 2007). In addition, the worldwide rate of child behavioural problems is approximately 20% (World Health Organization [WHO], 2005). Thus, the benefits derived from participating in parenting programs are seldom fully realised across communities (Prinz & Sanders, 2007).

A paradigm shift in the way evidence-based parenting interventions are developed, trialled and disseminated is currently underway. Fundamentally, the shift is away from a focus on the individual parent or family unit, towards a community-wide, population-level focus. Biglan et al. (2012) described the shift as being towards a public health paradigm that valued the prevalence of nurturing environments and has, at its core, multiple efforts that act to prevent most mental, emotional and behavioural disorders.

In an Australian context, there are increasing calls from respected researchers and institutions for a public health approach to parenting support. For example, Mullan and Higgins (2014) used data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children to explore how different types of family environments influenced child outcomes. The study demonstrated that there is a clear link between family environments and children's social and emotional wellbeing, and greater emphasis is required to provide families with evidence-based solutions. The authors concluded by calling for the adoption of a public health approach to promoting safe and supportive family environments. Providing all parents, regardless of their circumstances, with access to reliable, evidence-based, easy-to-access support, is critical to this shift in focus.

There are many examples of evidence-based parenting programs that are available around the world. One such program is The Incredible Years, developed by Carolyn Webster-Stratton and colleagues at the University of Washington's Parenting Clinic (Webster-Stratton, 1998). A core focus of the program is the relationship among parents, children and teachers, and the treatment of behavioural problems through a collaborative home and school environment. Other interventions offer more intensive support, such as The Nurse-Family Partnership established by David Olds, which incorporates a home-visit component to assist first-time mothers and their babies from birth, through to the age of two (Olds, 2006).

To help professionals working in the field navigate the programs available, several groups have established "evidence-based parenting clearinghouses" that offer a summary of all the available parenting programs in a particular region or area. Examples of clearinghouses include The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse (www.cebc4cw.org), and Blueprints for Violence Prevention (www.colorado.edu/cspv/blueprints/index.html). These sites typically sort programs via topic area (e.g., child welfare) and provide key information about each program including cost-effectiveness data, a rating of program evidence and how the program is delivered.

A recent analysis of parenting programs with Australian evaluation data identified 109 programs that targeted a combination of child, parent and family outcomes (Wade, Macvean, Falkiner, Devine & Mildon, 2012). The review used a Rapid Evaluation Assessment (REA) methodology that determined which parenting programs reporting parent, child or family outcomes had been evaluated in Australia and to identify the evidence for those programs. The effectiveness of each program was based on evidence from all papers found in the REA process. The evidence rating scale extended along a continuum from 1 to 6, where a 1 denoted Concerning Practice ("There is evidence of harm or risk to participants OR the overall weight of the evidence suggests a negative effect concerning practice on participants"), and 6 denoted Well Supported ("At least two RCTs have found the program to be significantly more effective than the comparison group").

Of all programs included in the analysis, the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program and its sister program, Stepping Stones Triple P, were the only programs to receive the highest rating of "well supported". The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program adopts a public health framework and, combined with the strength of evidence supporting it, provides an ideal case study for how to design and disseminate a system of parenting support within a public health framework in an Australian setting.

Triple P: Parenting as a public health priority

The Triple P-Positive Parenting program (Triple P) was developed by Sanders and colleagues at The University of Queensland. Triple P is built on the premise that there is no more important potentially modifiable target of preventive intervention and conceivably no more powerful means of enhancing the health and wellbeing of a community than evidence-based parenting practices. Triple P seeks to promote warm, responsive, consistent parenting that provides boundaries and contingent limits for children in a low-conflict family environment.

Triple P is built on the principle of proportionate universalism (Marmot, 2010) whereby it works as both an early intervention and prevention model to help create a society of healthy, happy, well-adjusted individuals with the skills and confidence they need to do well in life. To achieve this, Triple P targets the multiple factors that lay the foundation for lifelong prosperity for both the individual and broader community.

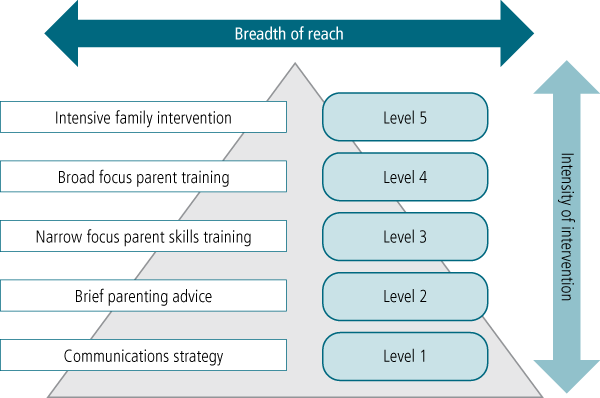

Triple P employs an iterative, consumer engagement model of program development to develop a range of evidence-based tailored variants and flexible delivery options (see Pickering & Sanders, 2013). The program targets children at five different developmental stages: infants, toddlers, pre-schoolers, primary schoolers and teenagers. Within each developmental period the reach of the intervention can vary from being very broad (targeting an entire population) to quite narrow (targeting only vulnerable high-risk children or parents). The five levels of Triple P incorporate universal media messages for all parents (Level 1), low intensity large group (Level 2), topic-specific parent discussion groups and individual programs (Level 3), intensive groups and individual programs (Level 4), and more intense offerings for high-risk or vulnerable parents (Level 5). Figure 1 and Table 1 describe Triple P's multilevel system of parenting support geared towards normalising and destigmatising parental participation in parenting education programs.

Figure 1: The Triple P model of graded reach and intensity of parenting and family support services

Note: Only program variants that have been trialled and are available for dissemination are included.

Source: Sanders, M. R. (2012)

| Level of intervention | Intensity | Program variant | Target population | Modes of delivery | Intervention methods used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | |||||

| Media and communication strategy on positive parenting | Very low intensity | Stay Positive | All parents and members of the community interested in information about parenting to promote children's development and prevent or manage common social, behavioural and emotional problems. | Website to promote engagement. May also include television programming, public advertising, radio spots, newspaper and magazine editorials. | Coordinated media and promotional campaign to raise awareness of parent issues, destigmatise and encourage participation in parenting programs. Involves electronic and print media. |

| Level 2 | |||||

| Brief parenting interventions | Low intensity | Selected Triple P Selected Teen Triple P Selected Stepping Stones Triple P | Parents interested in general parenting information and advice or with specific concerns about their child's development or behaviour. | Series of 90-minute stand-alone, large group parenting seminars; or one or two brief individual face-to-face or telephone consultations (up to 20 minutes). | Parenting information promoting healthy development or advice for a specific developmental issue or minor behavioural problem (e.g., bedtime difficulty). |

| Level 3 | |||||

| Narrow focus parenting programs | Low-moderate intensity | Primary Care Triple P Primary Care Teen Triple P Primary Care Stepping Stones Triple P | Parents with specific concerns, as above, who require brief consultations and active skills training. | Brief program (about 80 minutes) over three to four individual face-to-face or telephone sessions; or series of 2-hour stand-alone group sessions dealing with common topics (e.g., disobedience, hassle-free shopping). | Combination of advice, rehearsal and self-evaluation to teach parents to manage discrete child problems. Brief topic-specific parent discussion groups. |

| Level 4 | |||||

| Broad focus parenting programs | Moderate-high intensity | Standard Triple P Group Triple P Self-Directed Triple P Standard Teen Triple P Group Teen Triple P Self-Directed Teen Triple P Online Triple P | Parents wanting intensive training in positive parenting skills. | Intensive program (about 10 hours) with delivery options including ten 60-minute individual sessions; or five 2-hour group sessions with three brief telephone or home visit sessions; or ten self-directed workbook modules (with or without telephone sessions); or eight interactive online modules. | Broad focus sessions on improving parent-child interaction and the application of parenting skills to a broad range of targeted behaviours. Includes generalisation enhancement strategies. |

| Standard Stepping Stones Triple P Group Stepping Stones Triple P Self-Directed Stepping Stones Triple P | Parents of children with disabilities who have, or who are at risk of developing, behavioural or emotional problems. | Targeted program involving ten 60-90 minute individual sessions or 2-hour group sessions. | Parallel program with a focus on parenting children with disabilities. | ||

| Level 5 | |||||

| Intensive family interventions | High intensity | Enhanced Triple P | Parents of children with behavioural problems and concurrent family dysfunction such as parental depression or stress, or conflict between partners. | Adjunct individually tailored program with up to eight individual 60-minute sessions (may include home visits). | Modules include practice sessions to enhance parenting; mood management and stress-coping skills; and partner support skills. |

| Pathways Triple P | Parents at risk of maltreating their children. Targets anger management problems and other factors associated with abuse. | Adjunct program with three 60-minute individual sessions or 2-hour group sessions. | Modules include attribution retraining and anger management. | ||

| Lifestyle Triple P | Parents of overweight or obese children. Targets healthy eating and increasing activity levels as well as general child behaviour. | Intensive 14-session group program (including telephone consultations). | Program focuses on nutrition, healthy lifestyle and general parenting strategies. | ||

| Family Transitions Triple P | Parents going through separation or divorce. | Intensive 12-session group program (including telephone consultations). | Program focuses on coping skills, conflict management, general parenting strategies and developing a healthy co-parenting relationship. | ||

The evidence supporting Triple P

Triple P is built on more than 35 years of program development and evaluation. A recent meta-analysis of Triple P (Sanders, Kirby, Tellegen, & Day, 2014) looked at 101 studies (including 62 randomised controlled trials) involving more than 16,000 families. Studies were included in the analyses if they reported a Triple P evaluation, reported child or parent outcomes, and provided sufficient original data. In these analyses, significant moderate effect sizes were identified for children's social, emotional and behavioural outcomes (d = 0.473), parenting practices (d = 0.578), and parenting satisfaction and efficacy (d = 0.519). Significant small-to-moderate effects were also found for the distal outcomes of parental adjustment (d = 0.340) and parental relationship (d = 0.225). Significant positive effect sizes were found for each level of the Triple P system for children's social, emotional and behavioural outcomes, although greater effect sizes were found for the more intense interventions (levels 4 and 5). These results support the effectiveness of light-touch interventions (levels 1, 2 and 3) as affecting key parenting outcomes independently. Significant moderate to large effects were also found for various delivery modalities, including group, individual, phone and online delivery.

Targeting entire communities can be effective in changing population-level indices of children's social, emotional and behavioural problems. The approach, which involves targeting a geographically defined community and introducing the intervention model, has been carried out in several large-scale evaluations, several of which are in an Australian setting.

Sanders et al. (2008) implemented and evaluated the Every Family project. Every Family targeted parents of all 4-7 year old children in 20 geographical catchment areas in Australia. All parents in 10 geographic catchment areas could participate in various levels (depending on need and interest) of the multilevel Triple P suite of interventions. Interventions consisted of a media and communication strategy, parenting seminars, parenting groups and individually administered programs. These parents were then compared to a sample of parents from the other 10 care-as-usual geographical catchment areas. The evaluation of population-level outcomes was through a household survey of parents using a structured computer-assisted telephone interview. Following a 2-year intervention period, parents in the Triple P communities reported a greater reduction in behavioural and emotional problems in children, coercive parenting and parental depression and stress.

A further promising finding for Triple P in an Australian context emerged from a service-based evaluation of Triple P in New South Wales (Gaven & Schorer, 2013). The evaluation showed that children whose parents attended a Triple P course experienced significant behavioural and emotional improvements. There was a reduction in the number of children with clinically elevated scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman & Goodman, 2009), with approximately 10% of children moving from the clinical to the non-clinical range after Triple P. Practitioner reports of their experience in using Triple P were overwhelmingly positive. The practitioners identified that Triple P had helped them to do their job better, enhanced the services they could offer clients and increased their confidence in helping families. The study found that approximately 90% of practitioners would recommend Triple P to their colleagues.

Prinz, Sanders, Shapiro, Whitaker, & Lutzker (2009) conducted a ground-breaking study linking Triple P to the reduction of child maltreatment at a population level. The study involved randomising 18 counties in South Carolina (USA) to either the Triple P system or to care-as-usual control. Following intervention, the Triple P counties had lower rates of founded cases of child maltreatment, hospitalisations and injuries due to maltreatment and out-of-home placements due to maltreatment. This was the first time a parenting intervention has shown positive population-level effects on child maltreatment in a randomised design, and provides great promise for the potential value of a population approach to parenting support. It also demonstrates to policy-makers the potential of positive parenting programs to enhance the lives of individuals within the community and also the fabric of the community more broadly.

Two additional recent studies investigated the effects of Triple P as a public-health intervention. Sarkadi, Sampaio, Kelly, & Feldman (2014) evaluated Triple P when delivered in preschools in the form of large group seminars (Level 2) along with brief individual primary-care consultations (Level 3). They reported significantly greater health gains (12%) than preschools without the program (3%).

Fives, Pursell, Heary, Gabhainn, and Canavan (2014) evaluated a population-level rollout of Triple P. Approximately 1,500 families were selected at random from two Irish Midlands counties and interviewed before and after the implementation of Triple P. A feature of this evaluation was that the interviewed families may or may not have directly accessed Triple P. Results from these interviews were then compared with results from interviews with 1,500 families selected at random from a large, similarly matched county where Triple P was not delivered. Counties were matched on several criteria including socio-economic status, urban or rural setting, previous availability of parenting programs in the area and proximity to the intervention counties.

Significant population-level impacts were recorded across a range of child outcomes including clinically elevated emotional symptoms (29.7% decrease), conduct problems (30% decrease), peer problems (14% decrease), hyperactivity (27% decrease) and prosocial behaviour such as helping others (35% increase). A number of significant gains were also made at the population level for parenting outcomes and strategies. In the Triple P counties, the number of parents reporting psychological distress decreased by 32%, significantly more parents reported a good relationship with their child and significantly more reported using appropriate parenting strategies. In the Triple P counties, significantly more parents reported they were likely to use appropriate discipline following the implementation of Triple P and less likely to use inappropriate discipline for anxious behaviour.

How a public health approach to parenting support works

The rationale behind a public health approach to parenting support is that there are differing levels of dysfunction and behavioural disturbance in children and adolescents, and parents have different needs and preferences regarding the type, intensity and mode of assistance they may require. The multilevel approach of Triple P adopts the position of flexible delivery, tailoring the intensity of intervention to suit need, and selecting the "minimally sufficient" intervention as a guiding principle to serving the needs of parents in order to maximise efficiency, contain costs and ensure that the program becomes widely available to parents in the community. The model avoids a one-size-fits-all approach by using evidence-based tailored variants and flexible delivery options (e.g., web, group, individual, over the phone, self-directed) targeting diverse groups of parents. The multi-disciplinary nature of the program involves the use of the existing professional workforce in the task of promoting competent parenting.

The public health approach emphasises the universal relevance of parenting assistance so that the larger community of parents embraces and supports parents being involved in parenting programs. From a population-level perspective, intervention developers must consider how their program fits with local needs and policy, and be mindful of the cost-effectiveness of their proposed solution. Improved parenting is a potentially powerful cornerstone of any prevention and early intervention strategy designed to promote positive outcomes for children and the community. However, an effective parenting support strategy needs to address a number of significant challenges within a robust implementation framework in order to succeed (Damschroder & Hagedorn, 2011).

Parenting interventions need to be delivered in a non-stigmatising way. Currently, parenting interventions are perceived by many vulnerable and at-risk parents as only being for inadequate, ignorant, failed or wayward parents. To be effective, a whole-of-population approach to parenting support has to emphasise the universal relevance of parenting assistance so that the larger community of parents embraces and supports parents being involved in parenting programs. An example of a non-stigmatised program is prenatal (birth) classes, which parents across a broad array of economic and cultural groups (and family configurations) find useful and do not perceive as stigmatising. Parenting programs must be considered equally as "routine" as undertaking prenatal classes and preparing for life as a parent.

Parenting support needs to be flexible with respect to delivery formats (e.g., group, individual, online) to meet the needs of parents in the child welfare system. Having every family receive an intensive intervention at a single location is not only cost ineffective but also unnecessary and undesirable from a family's perspective. A careful consideration of the cost-effectiveness of interventions is essential when developing and disseminating programs at a population level.

Based on two economic analyses of the Triple P system, it is clear that a public health approach can be cost-effective. In one of the analyses (Aos et al., 2014), it was found that every $1 invested in the Triple P system (i.e., implementation of levels 1-5) yielded a $9 return in terms of reduced costs of children in the welfare system. In the other (Foster, Prinz, Sanders, & Shapiro, 2008), the infrastructure costs associated with implementing the Triple P system (i.e., levels 1-5) in the United States (Prinz et al., 2009) was $12 per participant, a cost estimated to be recoverable in a year by as little as a 10% reduction in the rate of abuse and neglect. Although these savings are striking, it is unclear who absorbs the cost of delivering parenting programs such as Triple P to the community.

Federal and state governments can choose to directly invest in these programs as part of their social welfare and mental health policies. However, in an environment of intense competition for public funds and resources, sustained investment in parenting programs is ultimately a matter of priority, which points to the importance of continued advocacy by researchers, agencies and consumers for government investment in prevention programs. Flexibility of program offering will also make the intervention useful for mandated services - parenting support for foster and adoptive parents and support for families within the child welfare system who are not involved with child protective services.

Investment in a population-wide rollout of Triple P would enable every Australian family to access quality evidence-based parenting information and support when needed, regardless of where they live. Under a population rollout, the vast majority of families would be able to access all the help they need through the multilevel suite of programs contained within the Triple P system media and communications campaigns, seminars, discussion groups and more intensive variants. The various programs that make up the Triple P system could be delivered by non-government organisations and community organisations as an additional tool under their existing Commonwealth and state funding and support programs. It could be promoted through non-stigmatising, universal access points such as day care services, kindergartens, playgroups, schools, churches and other community groups. Australian families would be free to choose whether they take advantage of the Triple P services.

Reliable measurement of population-level effects

There is a need for a national survey of parenting practices and child wellbeing outcomes in Australia using brief, reliable measures that are sensitive to change to document population-level program effects on children and parents. Such a survey would be valuable in documenting the impact of policy-level changes and in determining whether specific investments in programs achieved desired outcomes.

The survey would complement the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children by extending the scope to focus on measuring the targets of parenting interventions. Such data would enable community prevalence-rate data on positive and negative parenting practices and the community context of family functioning to be tracked over time. These epidemiological data would provide a valuable planning tool as well as allowing changes in parenting practices (improvements or deterioration) to be monitored over time.

From a policy perspective a regularly conducted comprehensive national parenting survey is consistent with goals of the National Framework for Protecting Australian Children and provides a direct means to describe the experiences of Australian parents in raising their children. The survey could be conducted every three years on a representative sample of Australian children aged 2-12 years and their parents. It could be designed to capture a range of child and parent variables that might be expected to change directly as a result of parenting interventions (e.g., parenting practices) or via changes in policy affecting families (e.g., financial stress) or be a predictor of change (e.g., socio-economic status, gender, family structure or changes in community context).

The development and implementation of a national parenting survey as an epidemiological tool to help evaluate the effects of policy-led changes in services to parents and families is essential. Such an instrument will provide a means for parents to express their opinions about the challenges they face raising their children, the type of help parents would find useful and the value they attach to the help received via parenting programs and the forms of family support. Reliable and change-sensitive measurement of parenting and child behaviour is crucial to the fidelity of a public health approach to parenting support.

Conclusion

There is clear evidence that the early years of children's lives shape their future, including their physical and mental health, learning capacity, social and emotional wellbeing and life opportunities. All aspects of adult human capital, from workforce skills to cooperative and lawful behaviour, build on capabilities developed during the childhood years. While all parents want the best for their child, many lack the tools to parent effectively.

To improve uptake of programs, a public health approach to parenting support is required. The Triple P system represents a transformational approach to improving the health and wellbeing of the community at large. To our knowledge, the Triple P system is the only parenting program shown to improve parenting practices and child development outcomes when evaluated at a population level. However, strengthening parenting and family relationships across the entire population can only occur if developers work synergistically with practitioners, agencies and policy-makers. When parents are empowered with the tools for personal change they require to parent their children positively, the resulting benefits for children, parents and the community are immense.

References

- Adamson, M., Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2013). Childhood feeding difficulties: A randomized controlled trial of a group-based parenting intervention. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(5), 293-302. doi:210.1097/DBP.1090b1013e3182961a3182938

- Aos, S., Lee, S., Drake, E., Pennuci, A., Klima, T., Miller et al. (2014). Return on investment: Evidence-based options to improve statewide outcomes (Document No. 11-07-1201). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute of Public Policy.

- Barkley, R. A., Edwards, G., Laneri, M., Fletcher, K., & Metevia, L. (2001). The efficacy of problem-solving communication training alone, behavior management training alone, and their combination for parent-adolescent conflict in teenagers with ADHD and ODD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 926-941.

- Biglan, A., Flay, B. R., Embry, D. D., & Sandler, I. N. (2012). The critical role of nurturing environments for promoting human well-being. American Psychologist, 67, 257-271. doi:10.1037/a0026796

- Chu, J. T. W., Farruggia, S. P., Sanders, M. R., & Ralph, A. (2012). Towards a public health approach to parenting programmes for parents of adolescents. Journal of Public Health, 34(S1), i41-i47. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdr123

- Comer, J. S., Chow, C., Chan, P., Cooper-Vince, C., & Wilson, L. A. S. (2013). Psychosocial treatment efficacy for disruptive behavior problems in young children: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 26-36.

- Connell, A. M., Dishion, T. J., Yasui, M., & Kavanagh, K. (2007). An adaptive approach to family intervention: Linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 568-579.

- Damschroder, L. J., & Hagedron, H. J. (2011). A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 194-205. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022284

- Dekovic, M., Janssens, J. M. A. M., & Van As, N. M. C. (2003). Family predictors of antisocial behavior in adolescence. Family Process, 42(2), 223-235.

- Dishion, T. J., & Andrews, D. W. (1995). Preventing escalation in problem behaviors with high-risk young adolescents: Immediate and 1-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(4), 538-548.

- Fives, A., Pursell, L., Heary, C., Nic Gabhainn, S., & Canavan, J. (2014). Evaluation of the Triple P programme in Longford and Westmeath. Athlone, Ireland: Longford Westmeath Parenting Partnership.

- Foster, E. M., Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., & Shapiro, C. J. (2008). The costs of a public health infrastructure for delivering parenting and family support. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 493-501. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.11.2002

- Gaven, S., & Schorer, J. (2013). From training to practice transformation: Implementing a public health parenting program. Family Matters, 93, 50-57.

- Goodman, A., & Goodman, R. (2009). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 400-403.

- Griffin, K. W., Botvin, G. J., Scheier, L. M., Diaz, T., & Miller, N. L. (2000). Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency and aggression among urban minority youth: Moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14(2), 174-184. doi:10.1037//0893-164X.14.2.174

- Heinrichs, N., Kliem, S., & Hahlweg, K. (2014). Four-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of Triple P group for parent and child outcomes. Prevention Science, 15(2), 233-245. doi:10.1007/s11121-012-0358-2

- Holzer, P., Higgins, J. R., Bromfield, L., & Higgins, D. (2006). The effectiveness of parent education and home visiting child maltreatment prevention programs. National Child Protection Clearinghouse, 24, 1-24.

- Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Parent management training: Treatment for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Luby, J., Belden, A., Botteron, K., Marrus, N., Harms, M. P., Babb, C., et al. (2013). The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: The mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(12), 1135-1142. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3139

- Marmot, M. (2010). Fair society health lives. London: The Marmot Review.

- Mason, W. A., Kosterman, R., Hawkins, J. D., Haggerty, K. P., & Spoth, R. L. (2003). Reducing adolescents' growth in substance use and delinquency: Randomized trial effects of a parent-training prevention intervention. Prevention Science, 4(3), 203-212.

- McCart, M. R., Priester, P. E., Davies, W. H., & Azen, R. (2006). Differential effectiveness of behavioral parent training and cognitive-behavioral therapy for antisocial youth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 527-543.

- Mejia, A., Calam, R., & Sanders, M. R. (2014). Examining delivery preferences and cultural relevance of an evidence-based parenting program in a low-resource setting of Central America: Approaching parents as consumers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, No Pagination Specified. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-9911-x

- Menting, A. T. A, de Castro, B. A., & Matthys, W. (2013). Effectiveness of the Incredible Years parent training to modify disruptive and prosocial child behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clincial Psychology Review, 33, 901-913. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.006

- Mitchell, C., Hobcraftb, J., McLanahanc, S. S., Siegeld, S. R., Bergd, A., Brooks-Gunne, J., et al. (2014). Social disadvantage, genetic sensitivity, and children's telomere length. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(16), 5944-5949. doi:10.1073/pnas.1404293111

- Morawska, A., Sanders, M. R., Goadby, E., Headley, C., Hodge, L., McAuliffe, C., et al. (2011). Is the Triple P-positive parenting program acceptable to parents from culturally diverse backgrounds? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20, 614-622. doi:10.1007/s10826-010-9436-x

- Mullan, K., & Higgins, D. (2014). A safe and supportive family environment for children: Key components and links to child outcomes (DSS Occasional Paper No. 52.). Canberra: Department of Social Services.

- Nowak, C., & Heinrichs, N. (2008). A comprehensive meta-analysis of Triple P-Positive Parenting Program using hierarchical linear modelling: Effectiveness and moderating variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11, 114-144. doi:10.1007/s10567-008-0033-0

- Olds, D. L. (2006). The Nurse-Family Partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27, 5-25. doi:10.1002/imhj.20077

- Pickering, J. A. & Sanders, M. R. (2013). Enhancing communities through the design and development of positive parenting interventions. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 4(2), Article 18. Retrieved from <digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol4/iss2/18>.

- Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1-12. doi:10.1007/s11121-009-0123-3

- Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2007). Adopting a population-level approach to parenting and family support interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 739-749.

- Rapee, R. M., Kennedy, S. J., Ingram, M., Edwards, S. L., & Sweeney, L. (2010). Altering the trajectory of anxiety in at-risk young children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1518-1525. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111619

- Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330-366. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.128.2.330

- Salari, R., Ralph, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2014). An efficacy trial: Positive parenting program for parents of teenagers. Behaviour Change, 31(1), 34-52. doi:10.1017/bec.2013.31

- Sanders, M. R. (2012). Development, evaluation, and multinational dissemination of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 345-379. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143104

- Sanders, M. R., & Pidgeon, A. (2011). The role of parenting programmes in the prevention of child maltreatment. Australian Psychologist, 46, 199-209. doi:10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00012.x

- Sanders, M. R., Cleghorn, G. J., Shepherd, R. W., & Patrick, M. (1996). Predictors of clinical improvement in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 24(1), 27-38.

- Sanders, M. R., Markie-Dadds, C., Rinaldis, M., Firman, D., & Baig, N. (2007). Using household survey data to inform policy decisions regarding the delivery of evidenced-based parenting interventions. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33, 768-783.

- Sanders, M. R., Ralph, A., Sofronoff, K., Gardiner, P., Thompson, R., Dwyer, S., & Bidwell, K. (2008). Every family: A population approach to reducing behavioral and emotional problems in children making the transition to school. Journal of Primary Prevention, 29, 197-222. doi:10.1007/s10935-008-0139-7

- Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). Towards a public health approach to parenting: A systemic review and meta-analysis of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 337-357. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003

- Sarkadi, A., Sampaio, F., Kelly, M. P., & Feldman, I. (2014). Using a population health lens when evaluating public health interventions: Case example of a parenting program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(7), 785-792. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.012.

- Spoth, R. L., Redmond, C., & Shin, C. (1998). Direct and indirect latent-variable parenting outcomes of two universal family-focused preventive interventions: Extending a public health-oriented research base. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(2), 385-399.

- Stallman, H. M., & Sanders, M. R. (2007). "Family Transitions Triple P": The theoretical basis and development of a program for parents going through divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 47(3-4), 133-153. doi:10.1300/J087v47n03_07

- Tellegen, C. L. & Sanders, M. R. (2014). A randomized controlled trial evaluating a brief parenting program with children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1193-2000. doi:10.1037/a0037246

- Turner, K. M. T., Richards, M., & Sanders, M. R. (2007). Randomised clinical trial of a group parent education programme for Australian indigenous families. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 43, 429-437. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01053.x

- Wade, C., Macvean, M., Falkiner, J., Devine, B., & Mildon, R. (2012). Evidence review: An analysis of the evidence for parenting interventions in Australia. Melbourne: Parenting Research Centre.

- Webster-Stratton, C. (1998). Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 715-730.

- West, F., Sanders, M. R., Cleghorn, G. J., & Davies, P. S. W. (2010). Randomised clinical trial of a family-based lifestyle intervention for childhood obesity involving parents as the exclusive agents of change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(12), 1170-1179. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.08.008

- Whittingham, K., Sanders, M. R., McKinlay, L., & Boyd, R. N. (2014). Interventions to reduce behavioral problems in children with cerebral palsy: An RCT. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3620

- Wilson, P., Rush, R., Hussey, S., Puckering, C., Sim, F., Allely, C. S., et al. (2012). How evidence-based is an 'evidence-based parenting program'? A PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis of Triple P. BMC Medicine, 10, 130. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-130

- World Health Organization. (2005). Child and adolescent mental health policies and plans. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

John A. Pickering is Head of the Triple P Innovation Precinct, Parenting and Family Support Centre, and Professor Matthew R. Sanders is Professor of Clinical Psychology and Director of the Parenting and Family Support Centre, both at The University of Queensland.

Disclosure statement: The Triple P Positive Parenting Program is owned by The University of Queensland (UQ). The university, through its main technology transfer company UniQuest Pty Limited, has licensed Triple P International Pty Ltd to disseminate the program worldwide. Royalties stemming from this dissemination activity are distributed to the Parenting and Family Support Centre, School of Psychology, UQ; Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences; and contributory authors. Matthew Sanders is the founder and an author on various Triple P programs and a consultant to Triple P International. No author has any share or ownership in Triple P International Pty Ltd.

The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: An example of a public health approach to evidence-based parenting support John A. Pickering and Matthew R. Sanders