Parenting in Australian families

A comparative study of Anglo, Torres Strait Islander, and Vietnamese communities

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

January 2000

Download Research report

Overview

This report is based on the Australian Institute of Family Studies Parenting-21 Project which began in 1995 as part of a major international research collaboration focusing on parents and children in several different countries. Findings from the final stage of the Australian component of the Parenting-21 study are presented around two key themes.

The first focuses on parents, children and the wider societal context, exploring issues such as how society views parents, how parenting is learned, who is responsible for parenting, how parents judge themselves, and the influences of the wider social context, for example, work and social support, on parenting.

The second theme focuses on parenting practices such as teaching children values, particularly via household chores, rules and the involvement of children in decision making; how parents approach discipline; and their long term goals for their children.

The research is drawn from primary data on parenting generated from samples of parents from three culturally diverse communities: Anglo, Vietnamese and Torres Strait Islander families. The influence of cultural background on parents' beliefs and practices is explored by comparing parents from the three cultural groups.

Foreword

In recent years there has been a growing interest among researchers in parents' own ideas about the tasks of parenting, about how they are going about the business of rearing children, about the sources they draw upon for their understanding of the nature of childhood, and about the resources they are able to access to support them in their roles as parents.

This project was established by the late Dr Harry McGurk who had a special interest and expertise in parenting issues. Harry was Director of the Australian Institute of Family Studies from 1994 to 1998. He considered that it was fundamental to a full understanding of the processes and outcomes of rearing children in contemporary society that the social context not be overlooked in the conceptualisation of parenting. Consideration, therefore, needed to be given to the ways in which individual parents go about the tasks of providing for, caring for, and interacting with their children, and to the economic, social and political conditions within which those tasks are framed in contemporary society.

Parenting-21 (the title refers to this Century) was a major cross-national research project under the Institute's Children and Parenting program. The Institute was as a member of an international collaboration known as the International Study of Parents, Children and Schools (ISPCS), involving researchers from Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United States. These research endeavours highlighted the significance of exploring parenting beliefs and practices in a variety of contexts, at a national and international level. It also underlined the importance of focusing on parents' understanding of parenting.

Violet Kolar, one of the authors of this publication, worked on the project from the outset, and took over the responsibility for it after Dr McGurk's death in April 1998. Her co-author, Grace Soriano, was the Research Officer for the Parenting-21 Extension Study which examined Torres Strait Islander parenting and in 1999 became part of the ISPCS group working on the Australian component of the study.

Their report is based on the perspective of parents themselves about how they approached the task of child rearing; how they perceived their competence as parents; the aspects of their family and community environments that helped them to achieve what they were trying to do for their children; and the supports, whether available to them or not, that would have facilitated their doing a better job.

Parenting in Australian families has a high level of policy relevance and will be a valuable resource for policy planners, service providers, researchers, and parents in general.

David I. Stanton

Director

Australian Institute of Family Studies

1. Introduction

Parents play a prominent role in the development and socialisation of their children. It is a complex endeavour, but the majority of parents raise their children successfully to live productive and fulfilling lives (McGurk 1996a). This fact is often overlooked, and generally there is little recognition when parenting is done well (Leach 1994). The social expectations on parents to fulfil their responsibilities in an acceptable way are enormous; how women juggle family and work commitments is one example. When things go wrong it is easy to blame parents especially for problems such as child maltreatment, drug abuse, juvenile crime, youth homelessness and suicide (McGurk 1996a; Richardson 1993). However, it is often forgotten that parenting does not occur in a social vacuum; rather it is influenced by the wider social, economic and political context in a given period of time. Thus, it is not just the individual parent characteristics but a host of complex variables, including the characteristics of the child and contextual factors, such as access to support networks and the nature of the marital relationship, which interact to affect parenting practices and, subsequently, outcomes for children (Luster and Okagaki 1993). Indeed, social problems such as those noted above could affect families even when one or both parents are loving, nurturing and supportive.

Parenting is the central theme of this report, which is based on data collected as part of the Parenting-21 project, conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies from 1996 to 1998. Parenting-21 is the Australian component of the International Study of Parents, Children and Schools, which involves researchers from Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United States. Focusing only on data from the Parenting-21 project, the specific aims of this report are twofold: the first is to describe how Australian parents are raising their children, by focusing on parents' beliefs and child-rearing practices. The second is to explore the influence of cultural background on those beliefs and practices by comparing parents from various cultural groups. Limited resources made it necessary to restrict the number of cultural groups; thus, it was decided that the selected groups should broadly reflect Australia's European, Asian and Indigenous cultures. Three samples of parents, selected from Anglo, Vietnamese and Torres Strait Islander families, form the basis of Parenting-21.

The literature generally categorises the values of Anglo and Asian communities, in particular, as representing opposing ends of a spectrum. For example, Anglo culture is often categorised as espousing values of independence and assertiveness, while Asian cultural values are often defined in terms of dependence and conformity (Nguyen and Ho 1995; McDonald 1995). Little is understood about parenting in Indigenous cultures. In general, there is a public perception that there is great disparity between the parenting practices of different cultural groups.

Taking a primarily qualitative approach, this report on parenting presents findings around two key themes. The first focuses on parents, children and the wider societal context, exploring issues such as how society views parents, how parenting is learned, who is responsible for parenting, how parents judge themselves, and the influences of the wider social context, for example work and social support, on parenting. The second theme focuses on parenting practices such as teaching children values, particularly via household chores, rules, and the involvement of children in decision-making; how parents approach discipline; and their long-term goals for their children.

The intention is to give an account of parental beliefs and behaviours in contemporary parenting practices in Australia, and how they are influenced by the wider social context. Parents' beliefs have important implications for parental behaviour. While not always directly reflected in behaviour, beliefs nevertheless provide an important indication of the way that parents intend to approach their child-rearing responsibilities. Parents exercise considerable control over the physical and social settings to which children have access. Thus, a child's developmental context is shaped directly by parents exercising certain choices and indirectly through the impact on parent behaviour of both general policies and specific family initiatives.

The policy interest in families generally, and in parents and parenting in particular, is reflected in the Federal Government's recent launch of the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy. One part of this strategy emphasises funding parent education programs as a means of supporting parenting. The Parenting-21 project was not designed to address specific policy issues. Nevertheless, the project provides a breadth of primary data on parenting generated from samples of parents from three culturally diverse communities, which may prove to be an important resource for policy planners, service providers and family practitioners. Specifically, it may be of interest in relation to the development of parent education programs.

Parenting-21 was designed as an exploratory study, using data from volunteer samples of parents. Thus, the samples are not representative and the findings cannot necessarily be generalised to the wider population. Similarly, although the comparative component enables comment about the similarities and differences between the parenting styles of the three samples, the project was not designed to be an empirical test of similarity and difference between cultural groups. Finally, it should be noted that the project focused on parents of young children and thus explored developmental outcomes for children only indirectly, through the perspective of parents. It was not the intention of the project to investigate the impact of different parenting styles on child development.

2. Parenting and the socio-cultural context

Parenting has always been about the socialisation, care and development of children as future adults. However, contemporary parents are faced with a complex and challenging set of responsibilities that are vastly different from those experienced by their own mothers and fathers. Parents, more accurately mothers, were once expected to care for the physical and moral welfare of children (Richardson 1993). Social expectations have expanded and contemporary parents are now also responsible for their children's intellectual, social and emotional wellbeing (Richardson 1993). Encompassing a multitude of approaches, influences, outcomes, and significant relationships, parenting is bound and defined by a particular social and cultural context. As Heath (1995:161) pointed out: 'Societies throughout the world charge parents with the primary protection, socialisation, and nurturance of the children they bear or adopt . . . Parents are assigned legal responsibility to raise their children to be productive, responsible adults in accordance with the expectations of each particular community'. Ideas about parenting change quickly (Arendell 1997; Jamrozik and Sweeney 1996; Richardson 1993), with the social and cultural setting playing a major role in the type of parenting practices that are encouraged or constrained (Bowes and Hayes 1999; Harkness and Super 1995; Jamrozik and Sweeney 1996; McGurk 1996a). Thus, in order to understand parenting, not only is it important to consider characteristics of individual parents but it is also necessary to include the influence of the wider social and cultural context. This approach is based on the social ecology models advocated by Bronfenbrenner (1979), Garbarino (1995) and Harkness and Super (1996).

Ecological framework

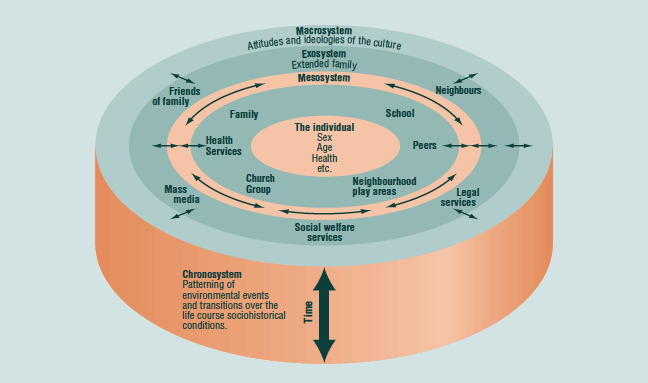

Bronfenbrenner's (1979) social ecology model offers a conceptualisation of child development as a 'social-psychological phenomenon' multiply determined by forces across four interactive levels, nested within each other. Bowes and Hayes (1999) presented a modification of this model (see Figure 1), in which the individual child is located within the microsystem (immediate family, school, peers, church and health services); the mesosystem (the interrelationships between settings in which the child is an active participant, for example the interaction between home and school); the exosystem (here the child is not directly involved but events occur that affect the child through influence on family members, for example the parent's place of work, the social networks of parents, and community influences); and the macrosystem (this relates to the broad societal and cultural context, which incorporates values and belief systems that influence the way that life is organised, passed on through social and government institutions) (Bowes and Hayes 1999; Bronfenbrenner 1979). As Bronfenbrenner stated: 'Public policy is a part of the macrosystem determining the specific properties of exo-, meso-, and microsystems that occur at the level of everyday life and steer the course of behaviour and development' (1979:9).

Bowes and Hayes (1999) added two additional components to Bronfenbrenner's model. The first acknowledges the choices made by individuals and the influences exerted through characteristics such as age, gender, health, and temperament. Thus, influence flows in both directions: from individual to context, and from context to individual. The second addition is the chronosystem, which recognises the element of time, acknowledging change in individuals as well as contexts. As Bowes and Hayes explained: 'Developmental and historical change needs to be taken into account in any model of the interrelationships between people and their context' (1999:11). An example of the influence of development is the difference in method of discipline used with children in kindergarten compared with children in high school (Bowes and Hayes 1999). The influence of historical time is reflected in the changed attitudes regarding, for example, the immunisation of young children (Bowes and Hayes 1999).

With regard to parenting, the model emphasises the importance of the social environment, identified in numerous studies, as a fundamental influence on parents' beliefs and the way they approach their child-rearing responsibilities (Bowes, Chalmers and Flanagan 1997; Grusec, Hastings and Mammone 1994; Harkness and Super 1996; LeVine 1988; Luster and Okagaki 1993; Youniss 1994). In addition, the model incorporates the influence of the cultural beliefs about children and childhood which inform parents' approaches to their responsibilities; the historical and economic contexts within which parenting and child-rearing are framed; and the social and political attitudes and values that influence the status granted parents and their children in contemporary society (McGurk and Kolar 1997).

Figure 1: Bronfenbrenner's Social Ecology Model

Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press, Australia, from J. M. Bowes and A. Hayes (Eds), Children, Families and Communties: Contexts and Consequences, 1997, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne.

The underlying premise of the model is that parenting is not only about the personal capacity and character of each parent, but is affected by a multitude of influences that include parents' cultural context, their access to resources, and the characteristics of individual children. According to Jamrozik and Sweeney (1996), access to resources comes via a number of avenues including employment or investment; the informal network of extended family, relatives and the community; and formally via the state. Acknowledging the interrelationships between the various layers in a society, particularly between family and community, is widely regarded as central to fostering a sense of community and feelings of social connectedness (Bowes and Hayes 1999; Tomison and Wise 1999; Winter 2000a; Winter 2000b).

Indeed, the increasing concern about the perceived decline of community life and spirit has focused attention to the concept of 'social capital'. This term encapsulates the notion that 'social relations of mutual benefit [are] characterised by norms of trust and reciprocity' (Winter 2000a). For a sustainable community it is important to have social relationships that are high in 'social capital' (Winter 2000b). Communities that nurture 'social capital' through the provision of information, services and support are likely to enable parents to deal with child-rearing stress and difficulties in a positive and supportive environment (Tomison and Wise 1999).

Similarities and differences in parenting

According to LeVine's (1988) model of parental behaviour, there are three goals shared by all parents, irrespective of culture. The first relates to the health and survival of the child; the second is about teaching the child those skills that are necessary to survive economically; and the third is to encourage those attributes that are valued by a particular culture. However, more specific attitudes and behaviours adopted by parents are culturally influenced. LeVine noted that: 'Each culture, drawing on its own symbolic traditions, supplies models for parental behaviour that, when implemented under local conditions, become culture-specific styles of parental commitment' (1988:8). Each culture, therefore, acts as a frame of reference for the way that children are perceived, and for the development of parenting beliefs and practices (Sims and Omaji 1999; Okagaki and Divecha 1993).

While parenting is an activity that occurs worldwide, the cultural variable represents a fundamental component of analysis (Harkness and Super 1999). This is a particularly important point given that much research has been based on white middle-class families (Deater-Deckard, Bates, Dodge, and Pettit 1996). Beliefs and practices about parenting can be so embedded within a culture that they are regarded as a matter of commonsense; thus, what occurs in another culture may seem peculiar and can be regarded as a deficit (Arendell 1997; Bornstein, Hayes, Azuma, Galperin, Maital, Ogino, Painter, Pascual, Pecheux, Rahn, Toda, Venuti, Vyt and Wright 1998; Deater-Deckard et al. 1996; Harkness and Super 1995; McGurk and Kolar 1997). The issue of physical punishment is an example that illustrates the point.

Physical punishment is a sensitive and contentious issue in Western societies and is generally regarded as having negative outcomes for children (Balson 1994; Dreikurs with Soltz 1995; Cashmore and de Haas 1995; Saunders and Goddard 1999). However, it cannot be assumed that physical punishment will carry the same meaning among different ethnic and cultural groups (Deater-Deckard et al. 1996). The main focus of the study by Deater-Deckard and colleagues was the relationship between physical punishment and child outcomes rather than the use of physical punishment per se. In comparing European American and African American parents, they found that physical punishment was associated with negative child outcomes, only among European American children (Deater-Deckard et al. 1996).

The basis of cross-cultural research as applied to parenting is to examine the similarities and differences in child-rearing approaches and how they influence children's developmental outcomes (Harkness and Super 1996). Importantly, cross-cultural research acknowledges the diversity in family life and child-rearing from one country to another, but also within a culture, varying between groups as well as over time (McGurk 1996a; Smith 1995). Bornstein and colleagues (1998) noted, however, that ideas about parenting are becoming increasingly homogeneous given the exposure to education and mass media. In a review of cross-cultural studies, Heath (1995) noted more similarities than differences had been found in parental involvement and parental expectations of children but emphasised that more fine-grained research might reveal more differences.

In his review of parenting studies that incorporated a perspective on cultural context, Youniss (1994) reported that parents were sensitive to the culture around them and the type of child-rearing strategies they adopted. For example, he referred to a 1990 study that investigated a group of Croatian parents who had migrated to North America. The parents were from a rural Croatian area and had immigrated to an ethnic enclave in an isolated section of an urban area in New Jersey. The parents had retained their religious and ethnic traditions and spoke their own language. These parents also wanted their children to embrace the Croatian identity, including its language and customs. Yet, in contrast to parents who remained in Croatia who valued compliance in their children and punished disobedience, they preferred their children to be self-directed. Such values were embraced by the middle-class of the host American culture (Youniss 1994).

Generally, parents adopt practices that they believe will benefit their children in their future social adaptation, regardless of the extent to which parents themselves are assimilated to the host culture (Youniss 1994). Thus, parenting practices are not set in concrete; they change historically, they differ according to social class, and they are altered as migrants move from one culture to another; there is also diversity within social classes and cultural groups (Youniss 1994; Arendell 1997; Okagaki and Divecha 1993).

Culture affects the social and employment opportunities available to parents, which serve to either encourage or hinder particular parenting behaviour; for example whether Western fathers are involved in the care of children (Harkness and Super 1995; Okagaki and Divecha 1993). Even though social expectations for fathers to be more involved in parenting have become stronger in Western culture, this has not been accompanied by actual increases in father involvement (Tomison 1998; Glezer 1991; Burdon 1994). Employment demands, especially increased hours at work, impact negatively on the role of both mothers and fathers, and the care of children (Arendell 1997; Bowes and Hayes 1999). In Australia, despite 'family-friendly' work initiatives, Probert argued that broader policy changes (market de-regulation and changes in the nature of work) are making it difficult for parents, especially mothers, to combine parenting and work (1999). As for fathers, Probert (1999:64) stated: 'Most striking of all, in fact, is the almost total absence of policy designed to help fathers balance work and family life, despite the evidence that they are finding this balance increasingly hard to achieve'.

Employment, together with social support and the marital relationship, comprise three important areas that can enhance or undermine parental competence and overall satisfaction (Arendell 1997; Cochran 1993; Okagaki and Divecha 1993). Support networks provide emotional and practical support and information, and represent a fundamental foundation for effective parenting. The marital relationship represents an important part of that emotional and practical support (Arendell 1997; Bowes and Hayes 1999; Cochran 1990, 1993; Gledhill 1996; Kolar and McGurk 1998; Tomison and Wise 1999).

Contemporary parenting

Parenting practices have been defined according to Baumrind's (1971) model of parenting styles. These have been identified as authoritative, where parent behaviour is loving and supportive, yet consistent and firm, and nurtures autonomy; authoritarian, where parents demand obedience from children and use punitive strategies when children do not comply; and permissive, where parents demand little of children and do not set boundaries (Baumrind 1971). Parenting behaviour influences developmental outcomes for children (Luster and Okagaki 1993; Arendell 1997). In Western societies, authoritative parenting is recognised as promoting positive developmental outcomes in children, such as social and intellectual competence, emotional security and independence (Arendell 1997; Baumrind 1971; Harvey 1998; Heath 1995; Smetana 1994). For example, in a review of cross-cultural research, Heath (1995) noted that those parents who had authoritative qualities, such as being supportive and using inductive methods (reasoning and explanation) in discipline, had children and adolescents who were socially competent.

As noted above, parenting beliefs and practices change over time, and contemporary parents are under enormous pressure regarding child-rearing responsibilities (Leach 1994; Richardson 1993). Social science research, mostly in the area of psychology, highlights the major influence of the parent role in regard to child development. Earlier generations of parents were primarily responsible for looking after the physical survival and development of their children (Richardson 1993). Nowadays, parents, especially mothers, are responsible for their children's social and intellectual competence, cognitive and moral development, and self-esteem (Richardson 1993). Richardson referred to this as the 'new job description of motherhood' which subsequently makes mothers increasingly the target for blame when things go wrong (1993:42).

Supporting this new job description is a burgeoning parenting information and advice business. Parents seeking advice or reassurance on how to raise their children can walk into any bookshop and be confronted by an extensive range of popular books on what to do and what not to do to ensure that children successfully grow to adulthood. Columns devoted to advice and tips on raising children are regular features in popular newspapers and magazines, and the same issues are addressed in the electronic media. All these present a rich resource of ‘expert’ advice and knowledge regarding child development and behaviour available to parents at relatively little cost. However, as Richardson (1993) pointed out, child care literature is diverse, regularly changing, and contradictory, which could lead to some parents feeling confused and uncertain about their own capacity to parent effectively.

Coontz (1992) argued that the considerable emphasis placed on the importance of parents to children's outcomes ignores the impact of the wider context. Parents are of course very important to their children's development and wellbeing but the experience of parenting is affected by the wider social, economic and political context. Resources are distributed unequally and parents need to have access to resources that will enhance their child-rearing responsibilities.

Coontz (1992:230) provided the following rationale for such resources: 'Just as most business ventures could never get off the ground were it not for public investment in the social overhead capital that subsidises their transportation and communication, parents need an infrastructure of education, health services, and social support networks to supplement the personal dedication and private resources they invest in child-rearing'.

Compared with the United States where families face limited support with services provided on a user-pays system, in Australia, support for families with young children is made widely available through universal services (Ochiltree 1999). These services were free (for example maternal and child health, child care services and preschools (kindergartens)) but in recent times have been subject to funding cuts, which have effectively restricted access and ultimately undermined parents' caring for children (Bowes and Hayes 1999; Ochiltree 1999; Brennan 1999; Leach 1994).

There has been growing recognition, however, that support for families is important. This was highlighted by the recent launch of the Federal Government's Stronger Families and Communities Strategy. Significantly, the strategy strongly promotes supporting families through the funding of parent education programs. The popularity of such programs is linked to what McGurk (1996a:2) described as: 'Firmly held assumptions that the responsibility for child-rearing rests exclusively with parents. It is a short step from such assumptions to the conclusion that social ills . . . are the outcomes, in the main, of inappropriate parenting. It follows, on this analysis, that if parents can be trained or educated to perform their child-rearing roles more effectively then many of these problems will be avoided'.

Perceptions of children and childhood

Parenting is a process that is intimately related to and affected by perceptions of children and childhood. As social constructs, childhood and parenting are subject to change from the influences of the wider social and cultural context. As Jamrozik and Sweeney (1996:13) noted: 'The changing images of childhood throughout history indicate that, at any given time, perceptions of childhood and corresponding attitudes toward children can be appropriately understood only in the context of the social structure and dominant interests of societies at that time.'

Table 1 provides a summary of the way children were perceived in different periods of time. The table illustrates the social foundations of childhood by showing the range of concepts of childhood as understood in various periods of history and how this was expressed formally, particularly in relation to the provision of children's services. As with parents, much of the impetus for the way children and childhood are perceived today has been heavily influenced by decades of social science research (Jamrozik and Sweeney 1996; Richardson 1993). One pervasive image of children in the West is as developing beings, good and innocent, with unlimited potential. Consequently, just as expectations have increased for parents, so have they also increased for children (Harvey 1998), who are expected to be 'faster, higher, smarter, younger' ('Good Weekend', The Age Magazine, 11 April 1998).

| Period of time | Concept of children | Description | Application of concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up to and including the middle ages | Little adults | Same weaknesses and faults as adults | No longer applied. |

| 17th Century (Calvinists) | Little demons | Potential for sin and corruption, need for discipline and guidance, potential to be good | Some child-welfare services. |

| 18th Century (Romanticists) | Noble savages | Natural, free, need for development without restraint, child-centred environment, child is essentially good | Elements found in some pre-school centres which focus on self-directed play. |

| 19th Century (Victorians) | Innocent beings | Time for fantasy and play, childhood as potential for happiness (and development), child innocent as well as good | Elements found in some child-centred environments and products (kindergartens, books with moral overtones, e.g. Fables). |

| 20th Century (Child psychologists and educationalists) | Developing beings | Childhood experiences crucial to stability and maturity in later life, childhood important for itself, children good, innocent and have unlimited potential | Child-centred institutions such as kindergartens, pre-schools. |

Reproduced by permission of Macmillan Education Australia, from A. Jamrozik and T. Sweeney, Children and Society: The Family, the State and Social Parenthood, 1996 (p.16), Macmillan Education Australia, South Melbourne.

Current Western perceptions also include negative images of children. For example, Christopher Green (1984), author of the popular parenting advice book Toddler Taming, described the young child as 'that negative, stubborn, self-centred terrorist toddler' (Green 1984:45). In a discussion paper addressing ways to overcome the structural barriers to child abuse and neglect, Tomison (1997) argued that in recent times, children have been negatively stereotyped in Western society. He described the way in which the two 10-year-old boys who were sentenced for the murder of 2-year-old James Bulger in the United Kingdom in 1993, were portrayed in the media as 'evil', 'monsters' and 'freaks' (Tomison 1997). He argued that, over time, the criticisms and negative descriptions of the two boys were subtly generalised such 'that the character of all children was impugned, challenging the concept of childhood innocence and the perception that children are "innately good"' (Tomison 1997:21).

The status of both parents and children is an important issue since it speaks to the extent that society is prepared to invest in future generations (Leach 1994). On the one hand, the role of parents is idealised, particularly the concept of motherhood (Richardson 1993; Bowes and Hayes 1999; Jamrozik and Sweeney 1996; Leach 1994), and children are recognised as a society's future. Yet on the other hand, caring for children is perceived as a low-status activity in society (Richardson 1993; McGurk 1996b). In the past, children were regarded as an economic asset because they could work. These days, even though children do bring benefits such as joy and love to their parents and the potential for future productivity, they are frequently presented as an economic liability in which they tend to be objectified, particularly in research such as that on the 'cost of children' (Jamrozik and Sweeney 1996; Quortrup 1997; Saunders and Goddard 1998). Quortrup comments that 'a balanced review of a family's use of resources would imply either sticking to an account of the whole family, or to account for both costs of children and costs of parents' (1997:99).

The view of children that is promoted via parenting literature and media, as well as via professional and informal networks, influences the image that parents hold about children. This in turn will affect the way that parents approach their child-rearing responsibilities (Backett 1982; Donovan 1987; Cashmore and de Haas 1995; Harkness and Super 1995, 1996; LeVine 1988; Okagaki and Divecha 1993; Youniss 1994). Disciplinary practices, particularly attitudes towards the use of physical punishment, also say a lot about the status and image of children in Western society (Balson 1994; Dreikurs with Soltz 1995; Saunders and Goddard 1998, 1999). Much of the parenting literature available to parents advocates an authoritative style of parenting (Harvey 1998) which incorporates the use of inductive methods such as explanation and reasoning (Papps, Walker, Trimboli and Trimboli 1995; Critchley, Sanson and Oberklaid 1998). However, there are parenting advice books that promote, for example, the use of rewards and punishments, which fall into the category of power-assertive disciplinary techniques (Papps et al. 1995; Critchley et al. 1998), and are punitive in nature. According to Balson (1994) and others (for example Dreikurs with Soltz 1995), rewards and punishments are part of an authoritarian style of parenting that does not sit easily in the context of a democratic social system.

Cross-cultural research in Australia

Cross-cultural research on parenting in Australia has been relatively limited and has tended to have a narrow focus. For example, Papps and colleagues (1995) explored the disciplinary practices that mothers from Anglo, Greek, Lebanese and Vietnamese communities used with their children. The researchers found that all groups most frequently used power-assertive methods (yelling, threatened use of force, and physical punishment); Vietnamese mothers used inductive methods (reasoning and explanation) more frequently than Anglo mothers (Papps et al. 1995).

Child-rearing values and practices were more broadly explored in a study undertaken in 1996 in Sydney, focusing on a sample of Japanese professional parents. The survey included issues such as children's desired character traits; discipline approach, importance of rules for children; parental responsibility; and aspirations parents had for their children (Andreoni and Fujimori 1998). The researchers found that: 'what is evolving is a particular form of Japanese multiculturalism: washitedoozezu, harmony without assimilation' (Andreoni and Fujimori 1998:69).

A recent pilot study investigated the process of adaptation in parenting practices among a group of recent migrant families from Africa (Sims and Omaji 1999). The researchers refer to the process of 'cultural mapping', which enables migrant parents to map their original frame of reference for parenting on to the frame of reference of the culture. Where child-rearing practices fall outside the boundaries of the mainstream culture, parents decide whether to keep, discard, or modify those practices. Indeed, practices that incorporate both the new and original strategies present an alternative to the process of assimilation, which has usually implied complete adoption of the practices of the mainstream culture and a rejection of those of the original culture (Sims and Omaji 1999).

For their sample of parents who had been in Australia for three years or less, Sims and Omaji (1999) found that the practices related to respect and punishment were particularly salient, with these parents perceiving dissonance between the values of their culture of origin and the host culture. In other words, teaching children respect was an important parental goal for this group of respondents, and they felt that Australian children lacked respect towards their parents and older people. For this group, physical punishment was an essential means of teaching children to conform, but they were aware that this conflicted with the Australian cultural view that physical punishment was inappropriate. This sample of parents resolved to maintain the parenting practices of their culture of origin (Sims and Omaji 1999).

Taking an international perspective, a study involving Australia and five other countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Sweden, and the United States) compared the involvement of children in household tasks (Bowes et al. 1997). Household work is an important means for passing cultural values on to children (Bowes et al. 1997; Goodnow 1996; Harkness and Super 1995). The study focused on the views of adolescents in relation to two forms of household tasks: self-care (making own bed, keeping bedroom tidy) and family-care (setting table for meals, helping with the dishes, washing the car). Their findings showed that Australian adolescents emphasised individual responsibility (self-reliance) more than responsibility to the family. In contrast, European adolescents emphasised responsibility to others. The researchers concluded that one way to encourage social responsibility in children might be to focus more on family-care tasks (Bowes et al. 1997).

According to Jamrozik and Sweeney: 'We have little research-generated knowledge of the ways and means families use to cope with daily tasks of child-care, economic management and personal relationships' (1996:60). They also saw a substantial gap between images of the ideal parent and parents' actual experiences (Jamrozik and Sweeney 1996). Parenting-21 seeks to contribute to the Australian literature on crosscultural studies in parenting.

3. The Parenting-21 study

The overall aim of Parenting-21 was to provide a comprehensive picture of how 'ordinary parents in ordinary Australian families are going about the task of bringing up children who are going to live the major part of their lives in the 21st century' (McGurk and Kolar 1997). Parenting-21 was conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies between 1996 and 1998, and is the source of the data presented in this report. Specifically, the project involved studying the relationships between parental beliefs, ideas and understanding about the nature of children and childhood, and actual child-rearing practices. It focused upon the rearing of children from infancy to middle childhood. Informed by an ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner 1979; Garbarino 1995; Bowes and Hayes 1999), the project collected information on the values and beliefs parents held about parenting and child-rearing; the aspirations, hopes and misgivings parents had for their children; their sources of information about parenting and children; their sources of help, advice and support with parenting; and how all these influenced the way they reared their children.

Australia's cultural context

The project sought to explore parenting from the perspective of parents themselves. It was important that the project provide a picture of parenting that reflects the diversity of Australia's families. Post-war immigration has been the major source of cultural diversity in Australia, leaving an indelible imprint on all facets of Australia's social, cultural and economic life (Batrouney and Stone 1998; Harvey 1994). Since 1945, Australia has seen the arrival of some 5.5 million people from as many as 170 countries. From 1945 to 1995, close to half of the newly-arrived immigrants were from the United Kingdom and Ireland; by 1995–96 just over 11 per cent of new arrivals were from these countries. The dismantling of the 'White Australia' policy in 1973 saw an increase in the number of immigrants from other countries, particularly Asian. In 1995, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS Statsite), 77 per cent of the total population of Australia were born in Australia and 23 per cent were born overseas. Of those born overseas, 13 per cent were born in Asia and, of this group, 29 per cent were born in Vietnam.

The Indigenous population comprise 1.7 per cent of the total Australian population. Of the total Indigenous population, 2.1 per cent are Torres Strait Islanders (ABS Statsite). The Torres Strait Islands lie 150 kilometres north of Cape York, the most northerly point of the Australian mainland. There are some 100 islands, but a population of nearly 80,000 people inhabits only 17 islands. Over 2000 Torres Strait Islanders live on or adjacent to Thursday Island. There are 14 Islander communities on 13 outer islands and two Islander communities on the adjacent mainland. These communities have populations of between 100 and 600 people. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, one-half of the Torres Strait Islanders are aged 0-24 years (Hunter, Batrouney, McGurk, Buchanan, Gela and Soriano 1999).

Brief profile of three cultural communities

These three broad groups – Australian-born, Asian-born and Indigenous populations – represent important components of Australia's general population and highlight its history of past and recent immigration. With over three-quarters of the total population born in Australia, the Anglo group represented the 'mainstream' culture and provided a base to compare parenting beliefs and practices with parents from Vietnamese and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds.

Anglo

There is no accurate or literal basis to the term 'Anglo Australian' although it is indicative, in a cultural sense, of a cultural group that originated in the United Kingdom and Western and Northern Europe (German, Dutch and Scandinavian) (McDonald 1995). Intermarriages between these groups over a 200-year period have blurred the distinctions between them in terms of family values (McDonald 1995). However, there is 'no homogeneity of values in regard to aspects of family and family life in Australia, even among the numerically dominant "mainstream"' (Hartley 1995:16). Some of the significant recent changes in values include cohabiting before marriage and women's participation in the workforce (Hartley 1995). Nevertheless, the majority of people continue to marry. Women tend to return to work after having children, but on a parttime basis during the years before children start school. In this regard, the husband continues to be regarded as the principal income earner with the wife's income seen as supplementary (McDonald 1995). Household tasks and responsibility for child-rearing continue to be traditionally defined with women largely responsible for domestic chores and as primary carers to their children (Glezer 1991; McDonald 1995). Such traditional arrangements are less likely to prevail in households where couples are professionally employed, where the wife is employed full-time, where couples are cohabiting and where they have remarried (Glezer 1991; McDonald 1995).

In terms of raising children, as has been noted, the parenting literature tends to promote an authoritative (loving, supportive, consistent, firm) as opposed to an authoritarian (strict, power-based, and punitive) style of parenting (Harvey 1998). However, a particular aspect of parenting can appear to be authoritarian while the overall approach is authoritative. This can occur, for example, with approaches to discipline where parents may incorporate the use of power-assertive methods which are typically associated with an authoritarian style of parenting (Papps et al. 1995). Ultimately, a typical parental goal is to raise children who are sociable, happy and independent (Dreikurs with Soltz 1995; Grose 1999). In general, parents live relatively close to extended family, especially grandparents, who tend to provide practical support such as child care (McDonald 1995; Millward 1992; d'Abbs 1991).

Vietnamese

In Vietnam, the family is the main provider of financial, social, physical and emotional support for all family members (Vuong 1996). The elderly are revered for their wisdom, life experiences and for contributions to their families and the community (Nguyen and Ho 1995). Within the family, roles are clearly delineated according to gender, with males taking on the role of provider with authority to decide on all matters, while the role of females is that of caretakers (Vuong 1996). Parents' approach to child-rearing varies according to the age and gender of children. With young children, parents are relatively tolerant, believing that young children are not responsible for their actions (Nguyen and Ho 1995).

In 1995, there were 146,600 Vietnamese who were born overseas, comprising 3.5 per cent of all overseas-born in Australia. The Vietnamese community began to grow in Australia after the fall of the South Vietnamese government, at the end of the Vietnam War in April 1975. Up until 1991, almost 80 per cent of Vietnamese migrants had spent time in refugee camps in various Asian countries. It is only in recent years that Vietnamese migrants (comprising partners, dependent children, middle-aged or elderly parents and close relatives of the original group) have been admitted directly from Vietnam for permanent settlement in Australia, most notably under the Family Reunion Program.

The composition and structure of Vietnamese families in Australia can be largely attributed to their unique migration experience. Unlike the traditional extended family in Vietnam, which tends to reside in one household, in Australia the extended family tends to stretch across a number of households, usually located in the same street or the same suburb. Thus, the common family structure in Australia does not include parents, children and grandparents living in one household. For grandparents, the experience of migration has not been easy. In general, they perceive that their status as revered family members has been compromised given that they tend to find themselves in the unexpected situation of being dependent on adult children in a foreign culture (Birrell 1993; Thomas and Balnaves 1993).

Economic necessity has seen an increase in the number of families where both parents work, which has challenged the traditional role of women in the family (Gold 1993). Nevertheless, the majority of married Vietnamese women continue to defer to their husbands in a number of family matters such as the discipline and education of children. The parent-child relationship can reflect the conflict between traditional parental values and those values acquired by children from their extra-familial socialising. The parent-child relationship can be further strained where parents lack English-language skills and knowledge of the new country (Nguyen and Ho 1996). A major motivating factor for parents is to ensure that their children receive a 'good' education. Parents strongly believe that education will secure for their children a successful career and bright future (Hartley and Mass 1987; Thai 2000).

Torres Strait Islander

Islander communities vary in the degree to which they have retained their cultural traditions or moved towards adopting Western values and practices. They continue to follow traditional and spiritual beliefs and practices but a majority of Islanders also follow one of various forms of Christianity, with the growth of fundamentalist churches being an important recent development. Values that hold the social fabric of Islander culture together include 'apassin' (having respect for and helping one another) and 'kozon' (sharing).

The clan system to which all families and individuals belong underlies the social fabric of Islander societies. Clan structures and kinship systems are extremely complex, informing relationships, obligations, social etiquette, and duties and privileges attached to the bonds of kinship. There are also duties and obligations attached to one's position in the social hierarchy, basically defined according to one's gender and age. Thus, male members are the head of their families and represent them in community meetings, while the eldest sibling in the family may have a status similar to parents, particularly when it comes to disciplining younger siblings. It is also the eldest sibling, usually the male, who represents the family on behalf of the father.

Among indigenous communities the kinship system, with the extended family at its core, ensures that the responsibility for parenting and child-rearing is shared among a host of 'significant others'. Parents have particular responsibility for providing children with a secure and nurturing environment. But, usually, responsibility for discipline, transmitting traditional values and skills and other cultural practices, is shared with a child's grandparents, aunts and uncles, from both sides of the family.

Method

The project employed a multiple-methods or triangulation approach (Denzin 1978; Minichiello, Aroni, Timewell, and Alexander 1990) to select the three samples and collect the data. This approach allows flexibility but it also 'adds rigor, breadth, and depth to any investigation' (Denzin and Lincoln 1994:2). There are various forms of triangulation (Denzin 1978; Creswell 1997); this study employed both methodological and simultaneous triangulation. The former involved the use of multiple methods for selecting the samples of families and the use of a number of data collection instruments, described below. The latter involved the use of both qualitative and quantitative research methods (Creswell 1997).

Sample selection

The method of recruiting respondents to the project was tailored for each sample and occurred over a three-year period.

Anglo

Families were defined as Anglo where the child and parents were Australian born, with grandparents born in either Australia or the United Kingdom. A total of 60 parents, with a child in one of five specific age groups (6 months, 18 months, 3 years, four-and-a-half years, seven to eight years), were interviewed in 1996. Three interviewers were employed to conduct interviews with the Anglo sample.

Recruitment for the Anglo sample began in February 1996 in the Melbourne metropolitan area, with a media release inviting parents of children aged between six months and eight-and-a-half years to register to take part in the project. The number of parents registering was boosted by the publicity resulting from a number of radio interviews and use of the snowball sampling technique. After this initial phase, parents were screened using CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing) to ascertain their eligibility for inclusion in the Anglo-Australian sample.

Vietnamese

Families were defined as Vietnamese where the child was born in Australia, with parents and grandparents born in Vietnam. This sample of parents also numbered 60 and had a child in one of the five age groups noted above; they were interviewed in 1997.

The recruiting of Vietnamese parents, who also resided in the Melbourne metropolitan area, was handled quite differently. A Vietnamese community worker with extensive experience working in the Vietnamese community and in interviewing was employed on the project. This person was solely responsible for publicising the project within the Vietnamese community, recruiting parents to the study, and conducting in-depth interviews.

Torres Strait Islander

In 1997, the Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Services of the Department of Health and Family Services awarded the Institute a contract to extend the scope of Parenting-21 to include families from the Torres Strait Islands. During the initial phase of the study, a Steering Committee was formed comprising four members from the Torres and Northern Peninsula Area Health Council. This Steering Committee was an invaluable source of local knowledge and Islander wisdom and assisted greatly in the identification of key informants who could act as contacts in the various communities and who would be able to identify and help recruit possible participants for the study. In order to introduce the study to the Torres Strait population various strategies were undertaken such as publishing in the print media (Torres News) a description of the project using the local-language and broadcasting through the local radio network (TSIMA).

The Anglo and Vietnamese components of Parenting-21 were essentially designed to explore parenting in an urban, industrialised setting. This contrasts dramatically with Islander life, which is non-urban and non-industrialised and has a social structure based on cooperation and reciprocity, and where parenting is a shared responsibility. Moreover, in Islander communities, information is exchanged through 'yarning' (sitting and talking). These considerations made it necessary to employ a less structured approach than that used with the two urban samples.

As a first step, a preliminary survey was conducted across a wide selection of islands in order to identify Islanders' parenting issues and concerns, to gather information about local circumstances and to identify the contacts within each community. Five islands were then selected as sites for fieldwork according to the following criteria:

- the diversity of communities in terms of cultures, histories, and stages of development;

- convenience factors such as distance, travel and accommodation costs; and

- acceptance by local communities and provision of support for fieldworkers.

Information provided by the Steering Committee and the results from the preliminary survey were used as a basis for recruiting participants. Two Project Officers, a male (Indigenous) and a female (Anglo long-time resident of the Islands), were recruited and focus groups were conducted from July to October 1998.

It was planned to hold family group discussions with a single extended family on each selected island. Focus group discussions would be held with the following groups: young parents (mothers and fathers who typically had a child in primary school); experienced parents (mothers and fathers who had at least one teenage child); and elders (typically grandparents). There would also be interviews with key informants such as teachers, nurses, health workers and social workers. The aim was to have at least six to eight people in each of the focus groups, giving a total of eighty-four participants.

Demographic profile

In the Anglo and Vietnamese groups, mothers were the main source of information (95 per cent and 83 per cent respectively). Most parents were married or cohabiting and had at least two children. The median ages for the Anglo sample was 34 years and for the Vietnamese sample 37 years. Seventy-eight per cent of Anglo parents had a tertiary qualification, and a high proportion was employed on a part-time basis. In contrast, 40 per cent of Vietnamese parents had a tertiary qualification, and most were not in paid work.

Several waves of Vietnamese immigration are reflected in the Parenting-21 sample; some parents had been in Australia between 17 and 19 years, while others were more recent arrivals with between three to eight years' residence.

With the Islander sample, non-attendance at focus groups in some cases resulted in data collection becoming opportunistic, with interviews and focus group discussions held as opportunities arose. The final number of respondents, including family group participants and key informants, totalled sixty-nine. The numbers of women and men were fairly evenly distributed with 29 mothers and 25 fathers. The median age for young mothers was 30 years, young fathers 28 years, experienced mothers 48 years, and experienced fathers 40 years. Only 38 parents mentioned their marital status; of this group, 45 per cent were married, close to 30 per cent were in a de facto relationship, with the remaining group single or widowed. The average number of children among all Islander respondents was three. Most respondents had not completed Year 12; those who went on to do further studies had completed a TAFE course. Nearly all the mothers (n=25) and around two-thirds of the fathers (n=19) responded to the question on employment; most of the mothers (n=15) and almost all of the fathers (one was retired) were employed. Within the group of key informants, eight were women and seven were men; the average age among them was 42 years.

Research instruments

Anglo and Vietnamese parents provided information about their child-rearing practices by means of a series of self-completed questionnaires. They then took part in a semistructured face-to-face interview in which child-rearing values and practices were explored in more detail.

For the Vietnamese sample, all research instruments were translated into Vietnamese. All interviews were conducted in Vietnamese with parents' responses written in English by the Vietnamese interviewer. Interviews were not tape-recorded. Vietnamese parents chose not to fill in the self-complete questionnaires separately, but left them to be completed by the interviewer in the face-to-face interview. The explanation offered by the Vietnamese interviewer was that filling in research questionnaires is not something that the Vietnamese community is accustomed to. Thus, interviews with Vietnamese parents lasted, on average, 6 hours compared with an average of 2 hours with Anglo parents.

The approach with Torres Strait Islander families was less structured, with general themes from the interview schedule adapted for use with the focus groups. Three sets of questions were prepared for discussion with the families selected for interviews, the focus group, and the key informants. Given this less structured means of data collection, it was not possible to incorporate a number of the questions pursued with Anglo and Vietnamese parents. Nevertheless, for each group, questions focused on family composition and interaction, and the parenting role. The two Project Officers generally conducted most of the interviews working together. The interviews were recorded as written notes as well as taped; these were subsequently transcribed. Interviews varied in length, with some lasting up to three hours.

Analysis and interpretation

The aim of Parenting-21 was to explore parenting beliefs and practices based on a phenomenological perspective (Smith 1995; Denzin 1978; Denzin and Lincoln 1994). Phenomenology was developed as a methodology by Husserl (1889-1938), a German philosopher, to resolve a number of fundamental philosophical issues (de Laine 1997). Essentially, the method involved stripping away (or 'bracketing', a term used by Husserl) preconceptions in order to arrive at the experience itself, whatever that experience may be.

In essence, phenomenology is the study, in-depth, of the human experience, including subjective perceptions, thoughts and feelings. In this case, the focus was on the meaning and experience of parenting for parents. The use of qualitative rather than quantitative data throughout this report enables themes in parenting to be identified, and gives a sense of the everyday experiences of three samples of parents. Further, parents' quotes are used intact, as far as possible, to convey the meaning and the feelings underlying what parents had expressed. The only exception has been to include words, which appear in square brackets, in order to clarify certain references.

The demographic profile indicates differences within the samples. Intra-group differences were particularly notable in the Vietnamese sample, which encompassed different waves of immigration. The experience of migration and the particular circumstances that underlie it affect the way that immigrant groups settle into their new environments (Menjivar 1997). Thus, Vietnamese families who arrived as refugees and have been in Australia for a number of years cannot be assumed to be similar to those who were non-refugees and arrived relatively recently. It was important, therefore, both to acknowledge the heterogeneity of the group and to give context to the responses. Accordingly, number of years in Australia is used as a principal identifier in all quotes included for Vietnamese parents.

Supplementary quantitative data are also presented, primarily for the purpose of summarising or clarifying issues.

Limitations of methodology

As described above, Parenting-21 employed multiple strategies in recruitment and data collection, raising issues of sample comparability. This prompts the question of whether differences (and for that matter, similarities) are real or a by-product of the adopted methodology. There is no simple answer to this. The essence of the project was exploratory, both in its focus and the methods employed. The findings provide a preliminary benchmark of a range of parenting beliefs and practices, which future research can further develop. Importantly, interpretation of the findings needs to be tempered by the limitations detailed below.

First, one of the problems associated with a phenomenological perspective, as with any other self-report method, is that of self-report biases. That is, it is possible that some participants in the Parenting-21 project may have under-reported what they perceived as less socially acceptable beliefs and practices. This may, for example, have arisen in relation to the use of physical punishment. However, there is no way to ascertain whether this was the case.

Second, the project relied on volunteers who were willing to express their views about parenting practices. Such views may well differ from those of parents who did not volunteer to participate. No doubt, there were parents who did not know about the study and so were not in a position to volunteer; and parents who were experiencing difficulties with family life in general or parenting in particular may have been unlikely to want to take part. Third, the sample of Anglo parents was skewed towards those well educated and financially secure, whereas the Vietnamese sample was more heterogeneous.

Fourth, it was generally mothers who took part in the research, a finding reflected in the wider parenting research literature. The role of fathers has largely been overlooked in research (Tomison 1998). This largely reflects the fact that mothers, in the main, continue to be responsible for the care and nurture of children (Glezer 1991).

Fifth, the translation of instruments for the Vietnamese sample means that it is not possible to ensure 'direct equivalence' (Andreoni and Fujimori 1998:71). That is, there may not be a shared meaning in the questions. For example, words such as dependence, submissiveness, indulgent or permissive, are valued in Vietnamese culture, yet in Western cultures, these very same words tend to be imbued with negative connotations (Nguyen and Ho 1995; Papps et al. 1995).

Finally, it has been noted by Hunter and colleagues that the structure of Islander focus groups (which included extended family and Islander elders) 'could lead to respondents being inhibited and deferential in the company of other family and community members' (1999:98). While it was not possible to obtain interviews from all likely informant groups and some interviews were completed as opportunities arose, a wide spectrum of views about Islander parenting was nevertheless obtained from all fieldwork sites (Hunter et al. 1999).

Because of these limitations, the findings may not be representative of all parents with young children or of the three communities involved. They therefore, should not be generalised to the wider population of parents. Parenting-21 was designed to be an exploratory study; its strength lies in the depth rather than the breadth of data collected. Therefore, it is a useful resource for policy planners and practitioners, as well as for parents in general, who may wish to compare their own beliefs and practices with those of other parents. It can also be used to inform the development of future parenting research.

4. The wider social context

Important aspects of parenting revolve around parents themselves, their children and the influence of the wider social context. These aspects are discussed around issues specifically related to: the status of parents; how parenting was learned; who was responsible for parenting; how parents judged themselves; their perceptions of children; what elements enhanced and hindered parenting; their sources of support; and the special contribution of the extended family network.

What it means to be a parent

To assess their experiences of the role of parent, respondents were asked to describe: ‘What does being a parent mean to you?’. Qualitative analysis of the interview data indicated that across all three samples, parents’ responses could be broadly classified into one of three themes: the status of the role of parents in the wider society; the impact of parenting on personal growth; and the day-to-day responsibilities of taking care of children. The theme of long-term goals was also highlighted, and is explored later in this report. The comments indicated that, generally, there appeared to be a shared understanding among the three samples of what it meant to be a parent.

Status of the role of parents in society

Anglo and Vietnamese parents highlighted the importance of the social context for parenting, particularly in terms of the status accorded to the parent role. In the examples below, acknowledgment of the significant role of parents as nurturers of a new generation of adults, as well as a future generation of parents, was juxtaposed with feelings of ambivalence and anger, and perceptions that parents were not generally valued:

‘Many times I feel angry and resentful about the fact that I’m nothing more than a parent and feeling, hearing myself say that and think – that is a terrible thing to say – because being a parent is crucial.’ (Anglo parent)

‘We play important role – to raise children, bring them up in a happy family. If they were spoiled then become bad element of the society – then it is parents’ fault.’ (Vietnamese parent, 11 years residence)

‘It really concerns me at the moment because so many people are saying to me – when are you going back to work. That makes me really angry because I think parenting is a really undervalued occupation. It’s about giving my children security and the best chance of absorbing the best values I can give them and possibly also helping them develop their gifts, helping them to be thinking, intelligent, responsible individuals.’ (Anglo parent)

The status of parents was also an important theme for Islander parents, but there was no ambivalence expressed about their role and that of the wider community. This may well be a reflection of the fact that parenting is regarded as a communal responsibility in Torres Strait Islander communities. Parents are supported in their role and it is recognised that other family members have an important contribution to make in child-rearing. The social hierarchy that underlies parenting in Islander communities is an example of cooperative and complementary roles undertaken by all family members. This contrasts starkly with the sentiments expressed by Anglo and Vietnamese parents and the social expectation that they were solely responsible for child -rearing. Indeed, Islander parents held the view that parenting in the ‘South’ was demanding and relatively unsupported. The following examples illustrate the above points:

‘The main strength of an individual is based on the immediate family and the main strength of the immediate family is based on the extended family, and the main strength of the extended family is based on the tribe.’ (Torres Strait Islander, key informant)

‘Everyone is there for everybody, for each other.’ (Torres Strait Islander, experienced mother)

‘[Can get] help from auntie next door, couldn’t ask next door there [down South].’ (Torres Strait Islander, young father)

Impact of parenting on personal growth

The parent-child dyad is a two-way relationship. That is, just as parents affect the development of children so children themselves may affect the development of parents’ ideas, expectations and behaviours (Okagaki and Divecha 1993; Schaffer 1996). This notion of parenting as a period of personal growth for parents was succinctly summarised by an Anglo parent in the following way:

‘It’s a learning experience and you just keep on. New things keep on coming up all the time and you’ve got to keep on changing, adapting, and as they get older you’ve also got to keep on adapting to different changes in their life as well.’ (Anglo parent)

Among Vietnamese parents, the theme was alluded to in a general way; parents talked about aspects of the parent–child relationship using references such as ‘mutual trust’, ‘having children also affects your life’, and ‘to have children is a marvellous thing, married and children is complete happiness’.

With Islander parents, the theme was implied in comments about changing lifestyles and shifting priorities associated with becoming a parent. Having children was said to ‘open up a whole new world’. Parents also spoke of experiencing a range of emotions including pride, love, and happiness:

‘Being a mum makes me happy . . . you know . . . I use to be like this – ahh, I don’t want to have any children . . . but when I had her, it was different . . . it’s totally different, a whole new world, you’re responsible and you have to be responsible.’ (Torres Strait Islander, young mother)

Day-to-day parenting responsibilities

With Anglo and Vietnamese samples, one of the themes highlighted in the responses related to the day-to-day responsibilities involved in parenting. These included references to the basic tasks of daily child care; the joys and frustrations of parenting; and the delights of watching a child grow:

‘I think being there for your children, looking after them, teaching them to smile and the importance of that, and just being happy in themselves, I think are the important things. So my role in being a parent is organising all of that and, you know, the other things of diet and sleeping properly and all that sort of stuff.’ (Anglo parent)

‘Responsibility to bring up your children, feed them, discipline them, love them.’ (Vietnamese parent, 3 years residence)

Islander parents also referred to a range of parental responsibilities. These included the physical and emotional care of children when ‘sick or hurt, nurse them’; and ‘hold, hug and try to make them feel good’; ‘someone they can talk to’. Others spoke about the importance of ‘earning a living so can provide for family’, ‘feed the family’.

Learning about parenting

As Neven (1996:53) noted, ‘parents are not made at birth but become parents over time’. Despite the range and nature of the responsibilities involved, parenting is largely a process for which there is no formal training or educational qualification. Nevertheless, future parents may well have some general ideas about children and parenting, ideas that are moulded by multiple influences (Arendell 1997; Okagaki and Divecha 1993). Previous research indicates that, generally, parents’ ideas about children and their own parenting are influenced by their own family of origin; other informal sources (such as other relatives, friends, and neighbours); and formal sources (such as parenting books and professionals working with families) (Harkness, Super and Keefer 1992). While these three areas of influence are important to the development of parenting, family of origin represents a major source of influence.

To explore family of origin and its possible influence in shaping parenting values and practices, Anglo and Vietnamese respondents were asked two questions regarding their child-rearing strategies: ‘What sorts of things would you do that are similar to your own mother and father?’ and ‘What sorts of things would you do that are different?’. The data provided for both qualitative and quantitative analysis not only enabling similarities and differences to be analysed, but also providing a summary rating for the family-of-origin model. The salience of family background was also illustrated in the Torres Strait Islander data despite the fact that Islander parents were not asked the above

Themes of similarity and difference

The legacy of childhood was revealed in the way parents spoke about their mothers and fathers, and their respective approaches to parenting. Several interrelated themes emerged as valued aspects of parenting, relevant to both Anglo and Vietnamese parents. These included: personal qualities (being respectful, tolerant, patient and committed, and possessing a sense of humour); being emotionally and physically nurturing (fostering self-esteem, stability, harmony and loving relationships); being able to communicate with children (talking and listening); being involved and available (spending time and playing with children, generally being interested and able to enjoy their company, and being physically present); and the use of an authoritative discipline approach (consistent approach, clear rules and boundaries, and democratic styles).

The examples below illustrate the salience of personal upbringing for Anglo and Vietnamese parents, and its influence on subsequent parenting behaviour:

‘Mum was very loving, and when I have difficulty with [my child] I think of my mother who was always calm in all those situations.’ (personal qualities – Anglo parent)

‘Dad was very creative in what he did. We learned a lot about equipment, building things etc. . . . we were involved in what he did. We try to involve our kids in projects, we work together.’ (involvement – Anglo parent)

‘[Like my mother] I take care of my children well, [like her I am a] kind, loving and caring mother.’ (emotional/physical nurturing and personal qualities – Vietnamese parent, 6 years residence)

When talking about the aspects of their own parents’ style they had changed or rejected, respondents referred to characteristics that were opposite to those traits they valued. Thus, for example, negative aspects of ‘personal qualities’ included references such as arrogance, being disrespectful, impatient or intolerant. As with the positive comments noted above, Anglo and Vietnamese respondents were also explicit regarding the aspects they rejected in their own mothers and fathers, and the way this affected how they raised their own children:

‘I do a lot of things different in how I talk to my children, for example, my father, he would say – oh, you’re hopeless, you’re useless – whereas I would never ever say that to my children.’ (parent/child communication, emotional nurturing – Anglo parent)

‘My mother was mainly responsible for discipline and she often over-reacted, so I would be more cautious about going crook at the kids just because I feel uptight. Punishment shouldn’t be so severe, just something to get your message across effectively.’ (discipline – Anglo parent)

‘My mother was too modest, she did not praise her children . . . I praise and encourage my children.’ (emotional and physical nurturing – Vietnamese parent, 16 years residence)

‘My father was extremely strict, he never play and smile with [his] children.’ (discipline – Vietnamese parent, 19 years residence)

As noted, Torres Strait Islander parents were not asked specifically about the sorts of things they wanted to emulate or do differently from their own mothers and fathers. The data, nevertheless, suggested that the upbringing experienced by the parents had exerted a strong influence on how they raised their own children. This was particularly apparent when parents talked about their personal experiences of being disciplined and how they disciplined their own children (see section on discipline). A father’s involvement and love was fondly remembered by one parent while another parent spoke about her mother in negative terms:

‘My Dad, he was always with us, played sport with us, if Mum couldn’t make it to our sports, he was always there or sometimes they’d be there together . . . he used to give us love, tender loving care.’ (Torres Strait Islander, young mother)

‘I always talk to my children, like I had a lot of struggles in my life . . . like today I’m not a drunken mother . . . like my mother’s a drunken mother, sometimes she beat me, hit me.’ (Torres Strait Islander, experienced mother)

As noted earlier, the nature of parenting is gendered with women primarily responsible for child care (Glezer 1991; McDonald 1995). Indeed, this was reflected in the data from Anglo, Vietnamese and Torres Strait Islander families and appears in the section below on ‘Who is responsible for parenting and household tasks?’. Of interest, however, is that the data above show respondents were able to talk about learning parenting from both their mothers and their fathers.

Socio-cultural context