Review of government initiatives for reconciling work and family life

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Download Research report

Overview

This AIFS Research Report presents a review of government initiatives that help families balance their work and family responsibilities, highlighting innovative ideas and including a discussion of international trends and themes. Most of the information reviewed in this report pertains to OECD countries, especially New Zealand and countries in the European Union, as work and family policies have been extensively developed in these countries. Some East Asian countries have also been included, and for some countries, state (as opposed to federal) policies are discussed. The wide range of policies that have been used in different countries, combined with significant variation in approaches, means that those reviewed in this report are necessarily selective, and much of the discussion is quite broad. This review particularly focuses on government policies and approaches that address work and family issues for people with caring responsibilities for children or the elderly. The report outlines some of the broader aims, approaches and considerations of governments in the area of work and family, and then reviews policies related to leave and return-to-work policies; child care, child payments and early childhood education; working hours and other aspects of employment; and governance, support and promotion of work–family initiatives. This review reflects work–family policies that have recently been implemented (up to 2014) across developed countries, but not necessarily the state of play at the time of publication.

1. Introduction

This AIFS Research Report presents a review of government initiatives that help families balance their work and family responsibilities, highlighting innovative ideas and including a discussion of international trends and themes. Across the world, the importance of work–family policies to the wellbeing of families has been apparent for a number of decades now. The importance of these policies was highlighted through both the United Nations International Day of Families (in May 2012) and the East Asian Ministerial Forum on Families (EAMFF, 2–4 October 2012) having had themes of “Ensuring Work–Family Balance”. In addition, one of the key themes for the 20th anniversary of the International Year of the Family in 2014 was work–family balance, as highlighted in the publication, Family Futures (Griffiths, 2014).

This review focuses on policies and approaches implemented by governments that address work and family issues for people with caring responsibilities for children or the elderly. While work–family programs may be developed and are often implemented at the level of the workplace, we have focused here on policy development that has occurred at a state or national government level. Such policies include those related to parental leave, working hours, child care, and various other issues.

The wide range of strategies that have been used by different countries, combined with significant variation in approaches, means that the policies reviewed in this report are necessarily selective, and much of the discussion is quite broad. The references cited provide more detail for the interested reader. The annual series International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research (Moss, 2014, was the most recent issue at the time of writing) is especially valuable as a resource concerning work–family policies relating to families with children. Numerous other country-specific and cross-country examinations of work-family policies were also referenced in undertaking this review. Less information was available on work–family policies that related to those with other caring responsibilities, perhaps reflecting the relative lack of attention to work–family policies in this area. Throughout, we have referred to summaries and analyses of these policies by Kröger and Yeandle (2013), Lechner and Neal (1999) and Bernard and Phillips (2007). Of course, governments’ policy approaches can and do change over time, so this review should be considered to reflect work–family policies that have recently been implemented (generally, up to 2014) across developed countries, but not necessarily the state of play at the time of publication.

Most of the information reviewed in this report pertains to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, especially New Zealand (NZ) and countries in the European Union (EU), as work and family policies have been extensively developed in these countries. Some approaches of East Asian countries, such as Singapore, Japan and Korea, have also been noted. Some state (as opposed to federal) policies have been discussed where appropriate (for example, specific examples from selected states of the United States, and Québec, in Canada).

In the area of work and family, governments have taken different approaches, sometimes reflecting different objectives and funding arrangements. We begin, then, by providing an overview of some of these issues in section 2 of this report, before turning to the specifics of work–family policies and programs. The areas covered are as follows:

- leave and return-to-work policies (section 3);

- child care, child payments and early childhood education (section 4);

- working hours and other aspects of employment (section 5); and

- support and promotion of work–family initiatives (section 6).

The final section of the report draws out some of the overriding issues and challenges for the development of work–family policies.

Our review does not include detailed discussion of Australian work–family approaches. For a recent outline of work–family policies in Australia, refer to Hayes and Baxter (2014) and other articles pertaining to Australia in Griffiths (2014). For additional analyses and critiques of work–family programs in Australia, refer, for example, to Baird, Williamson, and Heron (2012), Burgess and Strachan (2005), Craig, Mullan, and Blaxland (2010), the OECD (2002, 2007), Skinner and Chapman (2013), Skinner, Hutchinson, and Pocock (2012), and Whitehouse, Baird, and Alexander (2014).

2. Work and family: Objectives and contexts

2.1 Policy objectives

A number of factors have led governments to develop policies to address work-family reconciliation. Pressures have come from workplace change, technological change, as well as demographic change. For example, the demise of the "standard" 9-to-5 work day means that long work hours and work during non-standard hours spills over into what has conventionally been family time. Also, technological advances have resulted in improvements in connectivity between home and work. This can both be helpful in managing work-family balance, and harmful in making it more difficult to keep work from encroaching into family time. Commuting time can also contribute to families' difficulties in managing their work and care responsibilities. A special case of this is with "fly-in-fly-out" employment that can be associated with a family member living apart from the family for days or weeks at a time. Demographic change - in particular, declines in fertility and the ageing of the population - have also been behind a focus on work-family policies, given an awareness of associations between availability for caring (for children and others) and workforce participation.

Each of the subsections below describes more specifically some of the objectives that have led to the development of work-family programs. These policy goals, as with the actual details of the policies, vary considerably across countries, and specific examples are provided.

Note that the policies covered in this report were not always developed with the explicit goal of addressing work and family issues. Neither were they always specifically aimed at those with caring responsibilities. For example, some of the policies reviewed in this report were developed to address labour productivity. Others were developed to address the broader concept of "work-life", in which it is recognised that it is not just those with family responsibilities who seek a better balance between work and outside-work interests.

Paid employment: The labour market

For some governments, building up the paid labour market is a significant concern, and some of the strategies discussed in this report were primarily developed to address this. For example, this has been an objective of work-family programs in the EU (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions [EFILWC], 2006). Most relevant to this report is the delivery of policies that provide supports for those with family responsibilities to engage in paid work, such as child care programs. However, other policies developed outside of the sphere of work and family have implications for those with family responsibilities, including those intended to stimulate growth in employment. The clearest example of this is in France, where the establishment of a 35-hour week had a primary objective of reducing unemployment. A secondary objective was to improve the quality of life for workers, given reduced work hours would mean more time for leisure or family (Hayden, 2006).

Paid employment: Financial wellbeing and social inclusion

An outcome of successful work-family policies - inasmuch as they enable more family members to work - is that poverty rates (including child poverty rates) can be reduced, and concerns about social exclusion addressed. Addressing such concerns has been a central goal of the UK government in its approach to work-family issues (OECD, 2005), and this has also been recognised in the EU (Commission of the European Communities, 2008c).

Paid employment: The wellbeing of workers

Paid employment can provide more than money; providing opportunities for social interaction and support, such that research has found that workers experience higher levels of self-esteem (London, Scott, Edin, & Hunter, 2004) and exhibit more positive parenting (Marks & MacDermid, 1996; Marshall & Barnett, 1993) compared to those outside of employment. However, work can spill over to families through loss of time or having more pressured time together, and to individuals by way of poorer health, wellbeing and life satisfaction (Pocock & Clarke, 2005; Strazdins, Clements, Korda, Broom, & D'Souza, 2006). A policy approach that addresses the employment conditions of workers may alleviate the negative consequences of work on family, and thereby improve outcomes for all family members, including children. Just as work can spill over to family, family can spill over to work. Family responsibilities can cause stress or time management difficulties that affect functioning at work (Barnett, 1994; Voydanoff, 2005), and so addressing issues of work-family spillover can have positive flow-on effects back to the workplace (Duxbury & Higgins, 2003).

Child wellbeing

Improved child wellbeing is a key objective of addressing financial and employee wellbeing through work-family policies, as discussed above. In the UK, promoting parental employment has been a major strategy in addressing child poverty, and in Canada also, addressing child wellbeing has been an objective of supporting families in work (OECD, 2005).

Also, the wellbeing of children is central in regard to the provision and use of non-parental child care. Even when child care policies are developed primarily to help address parental employment, the wellbeing of children is still a key concern. As such, the provision of high-quality child care and early childhood education has been an important focus of governments, to ensure families have access to options for their children that address minimum standards in quality. Where policies are developed in the related areas of early childhood education and school, work-family issues tend to be less-often considered, sometimes causing tensions between work and caring (see section 4).

Gender equity

An inability to combine work and family is more likely to result in women rather than men withdrawing from the labour market, since the unpaid work associated with caring is more often done by women. It is therefore women's employment that is affected more than men's when work-family supports, such as adequate child care and leave, are not available (Orloff, 2002). This affects women's earnings and future labour market involvement, having longer term implications for their financial wellbeing and placing them at greater risk of poverty (Commission of the European Communities, 2008c). Gender issues are therefore paramount in the area of work and family.

Improving gender equity has been a very significant priority in many countries, reinforced by the priorities of the EU and International Labour Organization (ILO), who advocate addressing gender equity through work-family policies (Commission of the European Communities, 2008c; ILO, 2009). The Nordic countries have a strong gender equity focus, with the aim of enabling men and women to be able to contribute equally to the paid labour market and also to take on equal sharing of care responsibilities (O'Brien, Brandth, & Kvande, 2007). A specific gender equity objective has been important in the development of working hours and child care policy elsewhere, including the Netherlands (OECD, 2007).

While work-family policies initially focused on improving ways for women to reconcile work and family, since the late 1990s the focus has shifted to men. Flexible leave options and parental leave policies have been targeted as a means of encouraging more equal take-up of family-friendly policies between men and women, and increasing men's involvement in care responsibilities (Moss, 2008; O'Brien et al., 2007). Several countries have followed this approach, not just because of gender equity, but also because, with mothers increasingly involved in the paid labour market, other options for caring for children or other family members have been needed. These changes have also been influenced by increased awareness of the benefits to children of having greater involvement with their father (O'Brien et al., 2007). The shift to father-oriented policies is an important one, for as long as family-friendly programs are considered relevant only to women, it is likely to be women who continue to shoulder the responsibility for caring.

In many countries, however, take-up rates of family-friendly work options continue to be lower for men than for women. This is in part explained by the gender gap in pay, which means that couples making decisions about who should curtail their labour market participation are likely to have the higher earner - usually the man - more fully employed (see the gender gap for selected OECD countries in Table 1). Beyond policy and financial reasons, broader cultural and attitudinal influences regarding the care of children or others are strong determinants of the roles men and women undertake.

Table 1 presents a number of key employment indicators for women among selected OECD countries, showing considerable diversity in the employment contexts across these countries. There are significant differences in female employment rates, and more specifically, maternal employment rates, with relatively low rates in Japan and Germany and relatively high rates in the Nordic countries. There are also large differences in the use of part-time work, with high rates for women in the Netherlands. Further, the gender wage gap is relatively large in Japan and Korea, while in countries such as Denmark, New Zealand, France and Poland, the gap between male and female earnings is narrower.

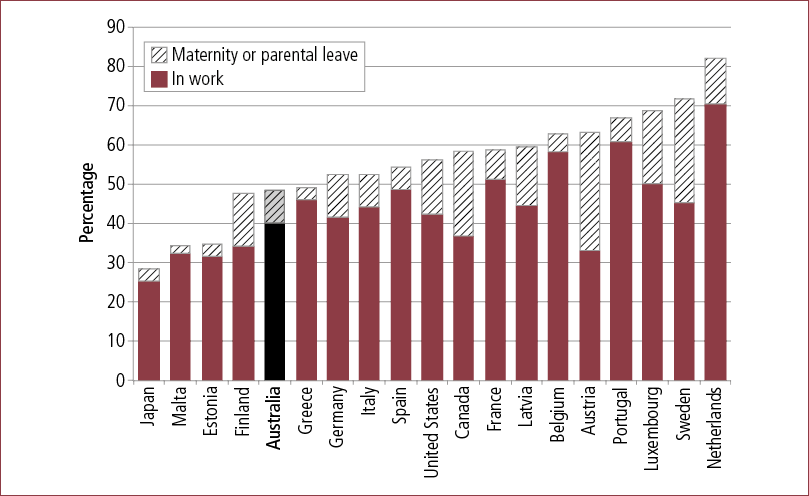

In almost all of the OECD countries listed in Table 1 employment rates are lower for mothers of children aged less than 3 years than for those with children aged 3-5 years. Maternal employment rates for mothers with children less than 3 years are also shown in Figure 1, separately showing the percentages in work and on maternity or parental leave. This is important - mothers who are employed are not all at work, and this varies considerably according to the availability of different maternity or parental leave arrangements (discussed in section 3).

| Employment/population ratio | All employed women, part-time employment, 2013 d (%) | Gender wage gap 2010 e (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All women, 2013 a (%) | Mothers, 2011 b (youngest child aged < 3) (%) | Mothers, 2011 b (youngest child aged 3-5) (%) | Single mothers 2009 c (%) | |||

| Australia | 68.3 | 48.3 | 58.5 | 52.0 | 38.1 | 20.4 |

| Austria | 68.6 | 66.3 | 68.1 | 78.3 | 33.3 | 24.1 |

| Belgium | 57.6 | 62.1 | 72.7 | 59.2 | 31.4 | 10.0 |

| Canada | 71.6 | 64.5 | 70.4 | 67.6 | 26.5 | 17.4 |

| Denmark | 71.2 | 71.4 | 77.8 | 82.0 | 24.7 | 14.7 |

| Finland | 69.0 | 51.8 | 76.0 | 70.2 | 16.7 | 20.6 |

| France | 60.9 | 58.1 | 69.5 | 69.9 | 22.5 | 19.9 |

| Germany | 70.1 | 52.8 | 65.5 | 64.6 | 37.9 | 18.9 |

| Greece | 40.5 | 49.2 | 55.4 | 76.0 | 15.6 | 9.3 |

| Hungary | 53.2 | 6.0 | 62.0 | 61.6 | 6.2 | 16.3 |

| Iceland | 83.1 | n.a. | n.a. | 81.0 | 24.6 | 20.6 |

| Ireland | 56.9 | 58.8 | 52.6 | 52.0 | 36.2 | n.a. |

| Italy | 47.7 | 53.4 | 50.6 | 76.4 | 32.8 | 12.4 |

| Japan | 68.8 | 29.8 | 47.9 | 85.4 | 36.2 | 29.4 |

| Luxembourg | 59.5 | 72.7 | 55.6 | 80.2 | 27.7 | n.a. |

| Netherlands | 70.8 | 75.8 | 75.6 | 63.8 | 61.1 | 20.4 |

| New Zealand | 71.2 | 42.2 | 61.3 | 54.4 | 33.4 | 11.4 |

| Norway | 75.5 | n.a. | n.a. | 69.0 | 28.8 | 14.7 |

| Portugal | 60.7 | 67.6 | 77.8 | 78.1 | 14.0 | 8.1 |

| Spain | 51.4 | 55.0 | 57.1 | 78.0 | 23.4 | 6.1 |

| Sweden | 74.4 | 71.9 | 81.3 | 81.1 | 18.4 | 18.2 |

| Switzerland | 76.6 | 58.3 | 61.7 | 67.0 | 45.7 | n.a. |

| United Kingdom | 68.5 | 56.9 | 61.2 | 51.8 | 38.7 | 21.3 |

| United States | 65.7 | 53.9 | 73.8 | 72.8 | 16.7 | 21.2 |

| OECD average | 59.9 | 52.2 | 65.6 | 67.0 | 26.1 | 17.3 |

Notes: a Data for female employment include women aged 15 and over.

b Data are for 2011 except for Finland and New Zealand (2009), Sweden (2007), Switzerland (2006), Japan (2005), Iceland (2002), and Denmark (1999). In the OECD database the Australian data were reported for mothers with a child aged less than 5 years (48.7%, as at 2009). The data shown here were calculated from the 2011 ABS Child Care and Education Survey Unit record file. Note that the percentage employed includes those on maternity or parental leave, which varies considerably across countries (refer to OECD, LMF1.2 Maternal employment).

c Data are for sole mothers aged 15-64 years, except for Canada, Denmark, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland, which show data for sole parents. Australian data were derived from ABS labour force data and refer to all single mothers with children aged under 15 years. Age ranges of children vary across other countries' statistics.

d Data are for 2009, except for Canada, Japan, Denmark, Switzerland and Sweden (2005); and New Zealand (2006).

e Data are as at 2010, except for Canada, Hungary, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, UK and US (2011); France and the Netherlands (2009); and Iceland (2008). The gender wage gap is unadjusted and is calculated as the difference between median earnings of men and women relative to median earnings of men. Estimates of earnings used in the calculations refer to gross earnings of full-time wage and salary workers. However, this definition may slightly vary from one country to another.

Sources: OECD employment database (downloaded August 2014, LFS by sex and age)

a OECD Family database (downloaded August 2014, LMF1.2 Maternal employment); Australian estimates are derived from ABS (2011) Child Care and Education Survey confidentialised unit record file

b OECD Family database (downloaded August 2014, LMF1.3 Maternal employment by family status); Australian estimate is from ABS Labour Force Status (ST FM1) by Sex, State, Relationship (downloaded July 2013)

c OECD Employment database (downloaded August 2014, FTPT employment based on a common definition)

d OECD Family database (downloaded August 2014, LMF1.5 Gender pay gaps for full-time workers and earnings by educational attainment)

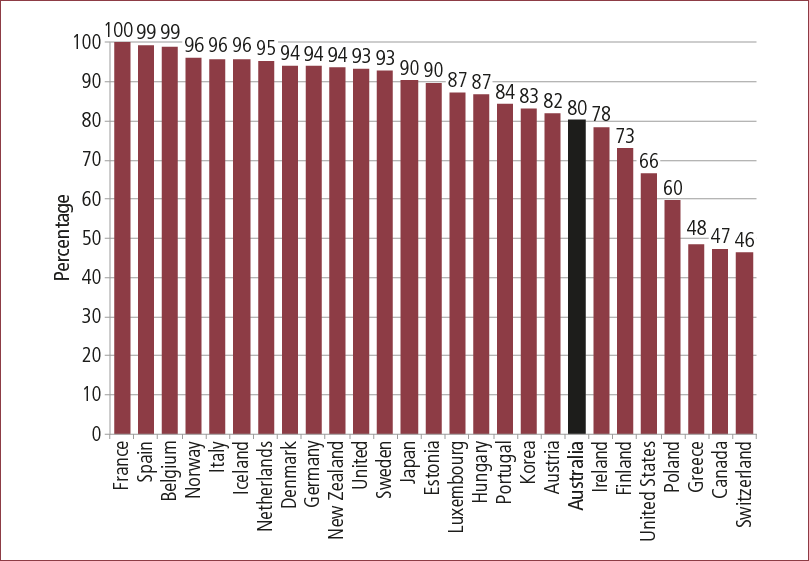

Figure 1: Employment of mothers with children aged less than 3 years, selected OECD countries, 2011

Note: The Australian figure is an estimate derived from the ABS 2011 Child Care and Education Survey. Total employed is differentiated into "in-work" and "on maternity or parental leave" based on actual hours worked previous week. Those who worked no hours or fewer than one hour are counted as "on maternity or parental leave". This is therefore an over-estimate since it includes those on forms of leave other than maternity leave. For notes about and sources for other countries, refer to OECD Family database, LMF1.2 Maternal employment. Data are as at 2011, except Finland and Malta (2009), Sweden (2006), Denmark (2004), and Canada and Japan (2003).

Source: OECD Family database (downloaded August 2014, LMF1.2 Maternal employment); Australian estimates are derived from ABS 2011 Child Care and Education Survey

Fertility

One response by men and women to perceived or actual difficulties in managing work-family balance is to minimise family obligations, or defer them for as long as possible. These responses result in men and women having fewer children than they might prefer, due to the effects of declining fertility levels among those who delay childbearing for too long (Gray, Qu, & Weston, 2008). In many countries it is recognised that women's difficulties in combining work and family may be contributing to their fertility decisions, and to subsequent lower aggregate fertility rates (Commission of the European Communities, 2008c). One reason, then, for developing good work and family policies, is to address concerns about fertility declines. Countries that have attempted to address fertility issues using work-family policies include Singapore (National Population and Talent Division, 2013), Japan (OECD, 2003; Ogawa, 2003) and Germany (Morel, 2007).

2.2 Work-family (and work-life) policies over the life course

As difficulties in balancing work and family are greatest within families with young children, many work-family policies focus on that life stage. Such policies include leave for parents for a period after the birth of a child or for other times children need care, access to flexible or otherwise suitable jobs on return to work, and addressing the availability of child care. The OECD has noted that to provide the most help to families with young children, it is best for governments to provide work-family policies that give a continuum of support across the life cycle (OECD, 2007), from the planning of births through to when children are grown up. Countries such as Sweden and Denmark provide such support. In other countries, such as the US and the Netherlands, there are policy gaps at particular times, such as when parental leave ends, or when children go to school. For example, the length of parental leave (and whether or not, and at what value, this is paid) in relation to the age at which children start preschool gives an indication of how long parents will be required to depend on other forms of care if intending to return to work at the end of the period of parental leave. Plantenga and Siegel (2005) reported considerable variation in this gap.1 The longest gaps were experienced by families in the Netherlands and Greece (around 185 weeks), while extended leave and/or early entrance to preschool made the gap far narrower in Finland, Spain, Hungary, Sweden and Latvia (around 40 weeks or less). Updated analysis of these gaps is also presented in the International Review of Parental Leave and Related Research series (see Moss, 2014).

Some governments have incorporated into their frameworks that caring responsibilities may include not only children, but also adults, so ensuring that policies are accessible to all those with caring responsibilities. For example, the Netherlands Work and Care Act 2001 applies to anyone with caring responsibilities. The definition of "caring responsibilities" is not uniform across countries, however, particularly in regard to whether the care recipient must be a relative or not, the severity of the condition of the care recipient, and whether the care recipient resides with the carer. For example, Hegewisch and Gornick (2008) reported that in New Zealand, "caring responsibilities" encompasses any relationship in which one person is caring for another, and is not restricted by any provision regarding the care recipient's needs.2 They noted that in the UK, the caring relationship must be with a relative, partner or someone living at the same residence.3 Like New Zealand, in the UK it was also decided that no limitations should be placed based on need, as incentives for abuse are low and the administrative burden caused by such a limitation is thought to be excessive.

As the labour force participation of women in later life increases, the ageing of the population progresses, and the care for elderly family members remains predominantly the responsibility of the family, elder care issues are expected to become more significant. Internationally, the development of work-family policies relevant to those with elder care responsibilities has not been expansive (Anderson, 2004; Kröger & Yeandle, 2013; Lechner & Neal, 1999). Governments have often focused more on policies directed towards the person needing care, rather than the caregiver (Lechner & Neal, 1999), although some governments have addressed elder care more fully. For example, the New Zealand government explicitly outlined a commitment to improve the choices of those caring for adults of all ages in its 2006 ten-year plan, Choices for Living, Caring and Working (Taskforce on Care Costs, 2007). The Japanese government has also explicitly recognised the needs of working carers, and several policies have been developed in this area (Neal & Hammer, 2007).

Many work-family policies for those with elder care responsibilities have evolved from those designed for families with children (Bernard & Phillips, 2007). However, there are important points where work-family policies for those with elder care responsibilities differ from policies for those caring for young children:

- For families with elder care responsibilities, the degree to which elder care supports or services are available in the community, and also the interaction with the health sector, are relevant.4

- Elder care responsibilities can be protracted and unpredictable. There may also be additional issues if the care recipient lives some distance from the care provider (Bernard & Phillips, 2007; Davey & Keeling, 2004).

- Workers with elder care responsibilities are likely to be older, and perhaps contemplating retirement themselves. It may be very important for these workers to remain in employment, despite their caring responsibilities, in order to preserve pension/superannuation entitlements and to ensure their longer term financial security. It might be particularly difficult for these workers to recommence employment if they need to leave work to undertake care responsibilities. Employers may be less willing to allow these workers access to flexible work options, especially if retirement or partial retirement is likely in the near future (Lechner & Neal, 1999). Also, employees may be less willing to ask for help with issues related to elder care than they are for child care (Bernard & Phillips, 2007).

Some countries have made their focus "work-life", rather than "work-family", policies acknowledging that those without family responsibilities also have a need to balance their work time with other elements of their life. This has been the approach in the Netherlands, Germany and France, regarding the right of all employees to access (or request) changes in working hours.5 As discussed by Hegewisch and Gornick (2008), broadening access can address gender equity issues and lessen the danger of a "mummy track".6 It can also be easier from a manager's perspective, in terms of having a range of people with differing yet possibly complementary scheduling preferences, and also in terms of avoiding resentment that can exist among those who would like to access but are not eligible for certain working arrangements.

2.3 Policy contexts

To fully understand different countries' approaches to work-family issues, it is necessary to consider how the policies in each country work together to form a "package", and to consider how they operate within country-specific economic, social, demographic, cultural and institutional contexts.

The range of policies and objectives across countries reflect different governments' priorities and policy approaches more generally. In some countries, a broad range of policy measures have been introduced to support families, such as the provision of services, funding of paid leave and regulation of employer behaviour through sanctions (e.g., Sweden and Denmark). In other countries, government intervention is minimal and the provision of work-family balance supports is left to employers (e.g., the US). Most countries fit in the middle of these two extremes and have a mix of government intervention and private provision (Hein, 2005). The different approaches countries have taken are founded in their overall approaches to social welfare, employment and family policy. The often-used classification of countries suggested by Esping-Anderson (1999) is useful way of thinking about these approaches:

- Liberal welfare states are characterised by relatively low levels of state-provided welfare, and a greater reliance on the market. Care needs are largely considered the responsibility of the family. State assistance is more often targeted to those in need, rather than being universally provided. Countries often classified as such include Australia, the US, the UK and Canada.

- In conservative welfare states the family is the central focus, and government support tends to reinforce the family as the main provider of welfare to individuals. Targeted assistance is available where this family-based (and primarily male breadwinner) model fails. Examples are Italy and Germany. Various policies exist in these countries in relation to parental leave and child care, but they are less about increasing maternal employment than they are about reinforcing families as the main care providers. Access to particular policies or entitlements tends to depend upon occupational status, rather than being equally available to everyone.

- In social democratic welfare states, state provision of services and benefits, equally available to everyone, is the central feature. There is a high degree of assistance to families, in the form of services and cash payments. Gender equity is an important goal, and therefore policies have been developed to facilitate women's involvement in employment, and increasingly, men's uptake of care responsibilities. These policies include comprehensive parental leave policies. Child care and elder care needs are also met by the state. Taxes are relatively high to fund these services and benefits. This is how Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Finland are classified.

While this classification is not thought to fully capture the differences across countries and types of welfare regimes, and various other classifications have been offered, it nevertheless shows some of the diversity in the environments in which work-family policy is being developed and applied (Blunsdon & McNeil, 2006; Edlund, 2007).

Country-level objectives are also influenced by those set out by supranational organisations such as the ILO and EU. The ILO has a particular role in promoting its Decent Work Agenda, which involves the four strategic pillars of: employment, rights at work, social protection and social dialogue, with additional cross-cutting objectives of gender equality and non-discrimination (Cruz, 2012). Various ILO conventions are relevant to the broad area of work and family, although the most closely related are no. 156, Workers With Family Responsibilities (with supplementary ILO Recommendation No. 165), and no. 183, Maternity Protection. (See Box 1 and the ILO [2009] publication Work and Family: The Way to Care is to Share!, which outlines and discusses ILO approaches). Countries that sign up to particular ILO conventions are required to submit regular reports and be supervised with regard to their government's adherence to the standards set out in a particular convention. 7The ILO report by Cruz (2012) summarises and provides some examples of country-level information on ILO Convention No. 156 and No. 183.

Box 1: International labour standard instruments on work and family

The Workers With Family Responsibilities Convention, 1981 (No. 156), and the Workers With Family Responsibilities Recommendation, 1981 (No. 165) are the main international standards addressing the issues and concerns regarding the reconciliation of work and family life. They provide considerable guidance on policies and measures which are needed to help workers with family responsibilities and to reduce work-family conflict. The foundation of the convention and recommendation is based on the principle of creating equality of opportunity and treatment in employment and occupation between men and women workers with and without family responsibilities.

ILO Convention No. 156 applies to all branches of economic activity and all categories of workers. Countries that ratify this convention make it the aim of national policy to enable persons with family responsibilities to exercise their right to obtain or engage in employment without being subject to discrimination and, to the extent possible, without conflict between their employment and family responsibilities. It also provides that all measures compatible with national conditions and possibilities shall be taken to:

- enable workers with family responsibilities to exercise free choice in employment;

- take account of their needs in terms and conditions of employment and in social security needs and community planning;

- develop or promote community services, such as child care and family services and facilities;

- provide vocational training and guidance to help workers with family responsibilities get into and remain in the labour force;

- promote information and education that contribute to a broader public understanding on the principle of equality of opportunity and treatment for men and women workers with family responsibilities.

Finally, it states that family responsibilities, as such, should not constitute a valid reason for termination of employment.

Source: International Labour Standard Instruments on Work and Family, <www.ilo.org/travail/aboutus/WCMS_119237/lang--en/index.htm>

Both the ILO and the EU have had a very significant focus on addressing gender equity through the development of appropriate work-family policies. The EU establishes a range of directives, targets and goals for member countries that relate specifically to gender equality and work-family policy (e.g., refer to Commission of the European Communities, 2008a, 2008c; EFILWC, 2006).

At the 2012 East Asian Ministerial Forum on Families, the "Brunei Darussalam Statement on Ensuring Work Family Balance" set out a range of issues that the governments of the participant countries agreed on in relation to the development of work-family policy.8 (See the Appendix for a copy of the statement.)

2.4 Implementation and funding of work-family policies

The implementation of governments' work-family policies varies across countries. Some policies may be written into legislation - for example, the 35-hour work week in France, and access to parental leave and rights to request flexible or part-time work in several countries - while others involve the government's provision of a range of supports and services (see examples in section 6). Of course, even when a policy is legislated, access to and take-up of that policy may depend upon the employers' roles in delivery of a policy, and depend on individuals' wishes or needs to make use of particular policies.

The funding of work-family policies - both the amounts directed to specific policies, and in the way funds are delivered - differ considerably across industrialised countries (Blunsdon & McNeil, 2006; Fagnani & Math, 2008). Typically, funds allocated to work-family policies in liberal welfare states are the lowest, as individuals depend upon such solutions to be made available by employers, as negotiated on an individual or collective basis. To varying degrees, there is some provision of public services such as early education for young children. At the other end of the spectrum, in the social democratic countries, benefits and services are provided to all, through a high tax base.

Many countries use social insurance (or social security) schemes to fund parental leave arrangements, as well as other entitlements, such as unemployment benefits. In these schemes, all employed people make contributions to a fund, which is also added to by employers and the state. Countries in which such schemes are used to fund paid maternity leave include Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and the UK. In Sweden, paid maternity leave is funded through health and parental insurance, which is also based on state and employee contributions, but the larger contributions are made by employers. Few countries require employers to fully bear the cost of parental leave, but in some (e.g., Switzerland and Germany) leave is funded partly by employers and partly through social security. Also, even when the parental leave scheme is fully funded through social insurance, rates of payment are often at less than 100% of prior earnings. Collective agreements within particular workplaces may provide for wage replacement to be topped up to 100% by employers (see Moss, 2014).

For governments, the costs of some policies can be significant, especially in regard to the public provision of child care. On the other hand, benefits to governments can accrue if child care (or other work-family policies) facilitates maternal employment and a subsequently larger tax base. Given the costs, these funding issues are important. As Gault and Lovell (2006) noted in their discussion of US work-family policies, "state and federal battles concerning leave policies and early care and education policies often stand or fall on the basis of cost and financing mechanisms" (p. 1156).

With the recent global recession, funding of work-family policies came under pressure in a number of countries. For example, since 2009 in Spain, there have been reductions in payments and/or income ceilings introduced for parents taking leave provided by regional governments (Escobedo & Meil, 2014). In Greece, the recent financial crisis resulted in significant changes affecting workers' rights, including reductions in minimum wage levels and, consequently, levels of unemployment and other payments (Hatzivarnava-Kazassi, 2012). Hatzivarnava-Kazassi also noted that work flexibility (including part-time work) increased, but without adequate or adequately enforced safeguards in place. Further, they noted that the poorer economic circumstances were likely to lead to lower take-up rates of leave in the private sector, due to fear of dismissal. A report on parental leave policies and the economic recession in Nordic countries (Parrukoski, Lammi-Taskula, & National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2012), on the other hand, noted that Iceland was the only Nordic country for which parental leave policies were affected by the global recession, with the most significant change being the lowering of the income ceiling for parental leave payments. The home child care allowance was also abolished in many municipalities. Eydal and Gíslason (2014) also noted that a proposed increase in parental leave in Iceland has been put on hold given the country's financial circumstances, pending a decision about how the increased leave would be financed.

2.5 Financial support to families and implications for employment

Governments vary in the way they support individuals and families - the total amount varies, as does whether this support is provided through cash payments or through the funding of services, and whether support is provided universally or targeted to those deemed to be most in need. Without aiming to summarise variation in these areas, below we identify some issues that are relevant to work-family decisions arising from particular approaches to government support. Further information and international comparisons can be found in OECD (2007) Babies and Bosses report.

Across OECD countries, financial arrangements to support individuals to remain out of employment are most often in place for the period immediately after a new child is born. This may be in the form of parental leave (see section 3.1) or child care payments (see section 4). The incentive to withdraw from employment to care for a child at this time is likely to be influenced by the availability and generosity of this financial support relative to potential wages. For those with higher earning potential, these payments may not be sufficient to encourage a withdrawal from work, while for those with lower earning potential, financial incentives to move into employment can be low. When children are very young, the availability and cost of non-parental child care will also be an important part of the decision. The degree to which governments subsidise the costs of non-parental child care varies considerably across countries.

Outside the period of time of new parenthood, governments may provide some financial support to those who are out of employment for other reasons. However, in most OECD countries, men and women are required to be seeking work in order to receive income support or social assistance, unless they have some other - for example, health-related - exemption. In a few countries, extended periods of support are available for not-working parents of young children, which can act as an incentive to remain out of employment for a longer time (see section 4).

Financial incentives to work are also affected by the availability of other support provided to families. Governments (including in Australia) often provide financial assistance to help with the costs of raising children through cash payments or the tax system, and government support can also be made through assistance with housing costs, health care costs and funding of school services. The "package" of assistance varies considerably across countries and within countries, and often varies in value according to family structure (couples versus single parents, and numbers of children) and family earnings (see Bradshaw & Finch, 2002). When these payments and services are targeted to those most in need, increased earnings from paid employment will reduce entitlements. Tests to determine eligibility for such benefits and allowances are often based on family, or couple, income. Therefore, for families with children, as the earnings of either parent increases, government entitlement to such payments may be withdrawn.

Financial disincentives to work may also apply to those who receive financial assistance for their provision of elder care, whether such payments are made directly by government or through the care recipient. However, it appears that financial assistance to carers, where it exists, is unlikely to generate large disincentives to enter the workforce, as these payments tend to be quite low in value. See the report of the Taskforce on Care Costs (2007) for examples of carer allowances in a range of countries.

In recognition that some working parents may not be able to access jobs with earnings sufficient to sustain a family - and to address issues of child poverty - various governments also have a system by which working parents are eligible for support (in-work support). This has been a major focus of the UK government, as a means of encouraging parents into work (the Working Tax Credit), and has also been the approach of the US, Canada and New Zealand (Brewer, Francesconi, Gregg, & Grogger, 2009). As stated by Brewer et al.:

These governments have used tax credits in an attempt to alleviate poverty without creating adverse incentives for participation in the labour market. In-work benefits achieve this goal by targeting low-income families with an income supplement that is contingent on work. (p. F1)

The availability of these in-work payments can be very important for those moving out of income support into employment, who otherwise might face a loss of government support greater than the gain in earnings.

The extent to which reducing engagement in employment for caring purposes is financially feasible is strongly related to the financial incentives generated by the tax and benefit systems of a country. While not conventionally thought of as work-family policies, their importance in framing choices regarding whether or not to take up paid employment, and how many hours to work, mean they have direct relevance to individuals in regard to work and family (Adema & Whiteford, 2008; Kelly, 2006; OECD, 2007). The take-home income from employment is affected not only by the initial wages, but by the amount and nature of taxation, and other payments such as social insurance contributions, that may vary with hours of work or levels of income.

Tax systems based on individual, rather than household, income provide stronger employment incentives for household members with lower potential earnings. Given the continuing gender wage gap in all OECD countries (Table 1), women are usually the lower earner in couples, and therefore most sensitive to such employment incentives. Most OECD countries' tax systems are now based on individual income. Tax systems vary in other ways, however; for example, in the extent to which tax rebates allow for a dependent spouse. This has implications for work decisions of the "dependent spouse", since this rebate will be lost if she takes up employment, and would need to be taken into account in determining the extent to which there were financial gains to her employment (OECD, 2007).

Where taxation is household-based - leading to income splitting within the household - the tax burden is put on the lower earners in families and because of the lower earnings of women, this type of taxation favours husbands and discourages wives from full-time employment (Jaumotte, 2003). The US and Germany are two countries in which taxable income is based on joint income for couples, and there are resulting disincentives for wives' employment (Haan, Morawski, & Myck, 2008; Kelly, 2006).

2.6 Summary

We have shown here that work-family policies have been developed with a range of objectives, and within a broad range of policy contexts. These contexts vary in the nature of the labour market and the degree to which women, and especially mothers, are engaged in paid work. There are additional factors that distinguish the OECD countries examined here (and distinguish countries over time), including economic conditions and societal or cultural views regarding maternal employment. We will see in this report that "work-family policies" are diverse in both their purpose and their design. Within a particular policy setting, the "package" of work-family policies is what is important in understanding how such policies affect how men and women can reconcile work and family across the life course, as they become parents, as their children grow, and also, if and when other caring needs arise. For those without such caring responsibilities, as well as those with them, policies developed to address work and family can be beneficial more broadly in consideration of work-life issues. The next sections now describe different work-family policies in more detail, again focusing on policies that have been developed at the government or state level.

1 This gap was the difference between "effective parental leave" - a measure incorporating the length and value of parental leave, as derived by Plantenga and Siegel (2005) - and the age of commencement in pre-primary school. This does not take into account that, for some countries, including Australia, the hours during which children attend preschool are likely to be too few to cover care needs. Commencement of primary school may be more appropriate as the end of the potential "gap" period in some countries.

2 A 2010 review of the New Zealand legislation recommended that the right to request flexible work arrangements be extended to all employees, not just those with caring responsibilities. See the Review of Part 6AA: Flexible Working Arrangements <www.dol.govt.nz/publications/research/part-6aa/potential-options.asp>.

3 "Partner" and "relative" are quite broadly defined (Taskforce on Care Costs, 2007).

4 For more extensive discussions on issues related to employed adults with elder care responsibilities, refer to Hegewisch & Gornick (2008), Hein (2005, pp. 90-94), Hoskins (1997), Kröger and Yeandle (2013), Lechner & Neal (1999), Merrill (1997), Neal & Hammer (2007), the Taskforce on Care Costs (2007), and Watson & Mears (1999).

5 There are some restriction that apply, such as length of tenure in current job, but no restrictions with respect to the nature of the caring responsibilities.

6 The "mummy track" is a term used to describe the lesser opportunities for career or work progression by women who combine work with motherhood.

7 These reports are available from the ILO website. For example, all reports and requests relating to ILO Convention No. 156 are listed at <tinyurl.com/qh56jmf>.

8 The forum was attended by official delegations from Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Vietnam.

3. Leave and return-to-work policies

Provision of leave to undertake caring responsibilities is clearly a central part of many governments' approaches to work-family issues. Details of different leave arrangements used for the care of children around the time of a birth are considered here first; that is, maternity, paternity and parental leave. Adoptive parents are usually able to access the same policies. The section also examines other types of leave, including those used for caring purposes.

In relation to leave from employment following a birth, while most countries have separate arrangements for maternity, paternity and parental leave, these separate arrangements are becoming less distinct, with some countries, such as Sweden and Iceland, having no specific period of maternity leave, but instead offering parental leave with a portion sanctioned for mothers (Moss, 2014). This is discussed further below.

Across OECD countries the variation in leave policies is vast, in relation to eligibility requirements, the length and remuneration of the leave, coverage and funding. This section does not provide a comprehensive review, but highlights some of the main differences. Across the EU, member states are required to adhere to minimum standards regarding maternity leave, parental leave and job protection for pregnant women, and new and breastfeeding mothers. This has occurred through the EU's 1992 maternity leave directives, and the 1996 and 2010 parental leave directives. Even across these countries some have more generous provisions than others.

3.1 Maternity leave

There are clearly gendered arrangements in place for the time immediately after the birth of a child in many countries, with maternity leave only applicable to mothers to provide a period of time for recovery from the pregnancy and birth, and time for breastfeeding and bonding with an infant. Maternity leave provides a job-protected absence from work for a period around the birth, including a number of weeks before and after. There is some variation across countries in regard to when maternity leave is to start (how many weeks before the birth), and also in regard to whether any or all of the maternity leave is obligatory.

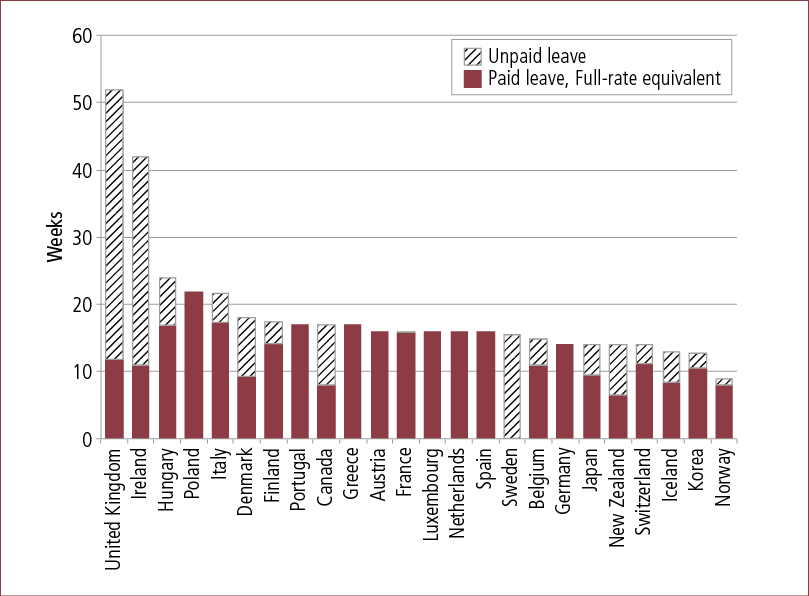

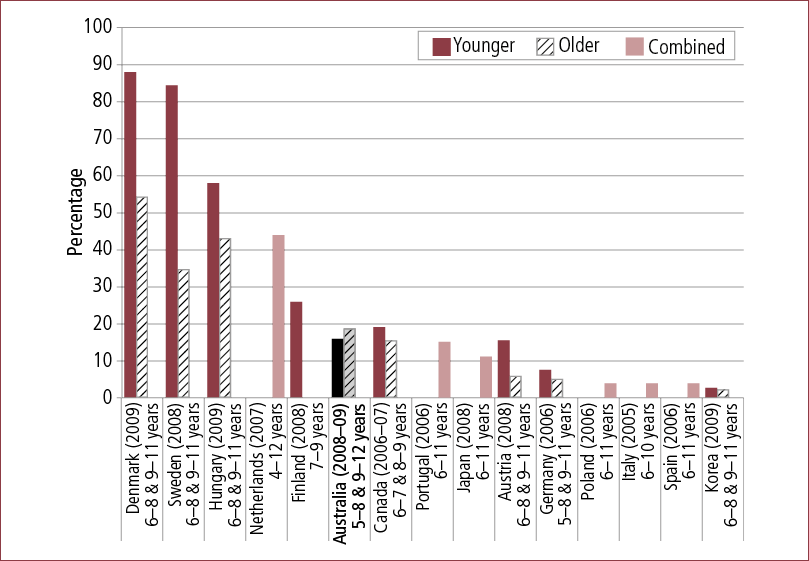

Paid maternity leave is offered in the vast majority of countries, although the rate and length of payment varies. The usual length of leave is between 14 and 18 weeks, paid at a percentage of prior earnings (usually between about 70% and 100%). As seen in Figure 2, the Scandinavian maternity leave entitlements are particularly generous, although Eastern European countries also have extensive maternity leave periods (see especially Bulgaria and Estonia, which have the longest periods of paid maternity leave). Some examples of maternity leave policies are given in Box 2.

Figure 2: Duration of employment-protected maternity leave, paid and unpaid, selected OECD countries, 2013

Note: Includes mother quota of parental leave. The entitlement to paid leave is presented as the full-rate equivalent (FRE) of the proportion of the duration of paid leave if it were paid at 100% of last earnings. FRE is calculated as duration of leave in weeks ´ payment (as a percentage of average wage earnings) received by the claimant. There are some inconsistencies in calculation across countries. For notes and sources for other countries, refer to OECD Family database, PF2.1 Key characteristics of parental leave systems.

Source: OECD Family database (downloaded August 2014), PF2.1 Key characteristics of parental leave systems

Box 2: Examples of maternity leave policies

| Belgium | Employees can take 15 weeks maternity leave (1 week before and 9 weeks after are obligatory). Self-employed women have 8 weeks of maternity leave. Employees in the public sector receive full salary, others receive 82% in the first month and 75% in remaining months (capped). Up to 2 weeks of leave can be taken as "free days" to allow mothers to more gradually return to work (Merla & Deven, 2014). This means using those "free days" along with reduced days at work for a period of time, rather than returning directly to usual work hours. |

|---|---|

| France | Maternity leave is obligatory. Mothers can access 16 weeks of leave at up to 100% of their earnings (capped in the private sector, although employers can make up the difference), including at least 2 weeks before the birth. Longer leave of 24 weeks is available to women having a third or higher order birth (Fagnani, Boyer, & Thevenon, 2014). |

| Japan | Women employees are entitled to 14 weeks of paid maternity leave at 66% of prior earnings, paid through a health insurance system, and financed by contributions from employees, employers, local government and the state. Six weeks of leave are obligatory (Nakazato & Nishimura, 2014). |

| United Kingdom | Mothers have access to leave for 52 weeks, of which 2 weeks' leave after the birth is obligatory. This leave comprises 6 weeks' payment at 90% of prior earnings (with no cap), 33 weeks paid at a low flat rate, and the remainder unpaid. Eligibility is based on employment conditions (employees with 26 weeks continuous employment with their employer, into the 50th week before the baby is due) and a minimum earnings test. Mothers who are not eligible for this leave may be eligible for a maternity allowance (O'Brien, Moss, & Daly, 2014). |

Maternity leave arrangements are particularly comprehensive in the EU through the maternity leave directives (most recently amended in 2008), which address working conditions as they relate to the safety and health of pregnant workers, workers who have recently given birth and breastfeeding mothers.9 The directives also provide for protection against dismissal. From 1996, all EU countries have been required to enact legislation that allows parents to care for children full-time for the first three months of their lives (Plantenga & Siegel, 2005). Many countries have policies in place that provide entitlements beyond those required in the 1996 directives (National Framework Committee for Work Life Balance Policies, 2007). Also, entitlements vary in many countries in the case of multiple births, disabled or very ill children, or in exceptional situations, such as if the mother or child dies.

Some innovation in maternity leave policy is evident in Portugal, where mothers can choose to take their leave over a longer period, paid at 80% of the usual rate. In Poland, mothers can access 26 or 52 weeks of paid maternity leave, with payment level somewhat lower if taken over 52 weeks. The first 20 weeks of leave is referred to as maternity leave (the balance referred to as parental leave), and of this, 14 weeks is obligatory. The remainder can be taken part-time (combined with part-time working), or can be transferred to the father (Michoñ & Kotowska, 2014).

Other countries' innovative approaches also relate to bringing fathers into the caring role by allowing for some of the maternity leave entitlement to be transferred to the father. This is possible in the Czech Republic, Croatia, Poland (as noted above), Portugal, Spain and the UK (Moss, 2014).

Quite different models apply in those countries that subsume maternity leave into the parental leave entitlement, such as in Sweden and Norway. In both these countries, parental leave entitlements are generous, allowing for a long period of leave with high wage replacement. Parental leave is discussed in section 3.3.

Paid maternity leave tends to have a high take-up rate. Taking all or part of the leave is obligatory in most countries (Moss, 2014). However, in most countries, the extent to which mothers are in employment prior to birth will significantly affect the proportion of mothers across the population who are able to take up paid maternity leave, as entitlement is often conditional on having previous work experience and subject to various job tenure restrictions. Many countries have an alternative allowance for those who are not eligible to an earnings-based payment (e.g., Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, United Kingdom) (Moss, 2014; National Framework Committee for Work Life Balance Policies, 2007).

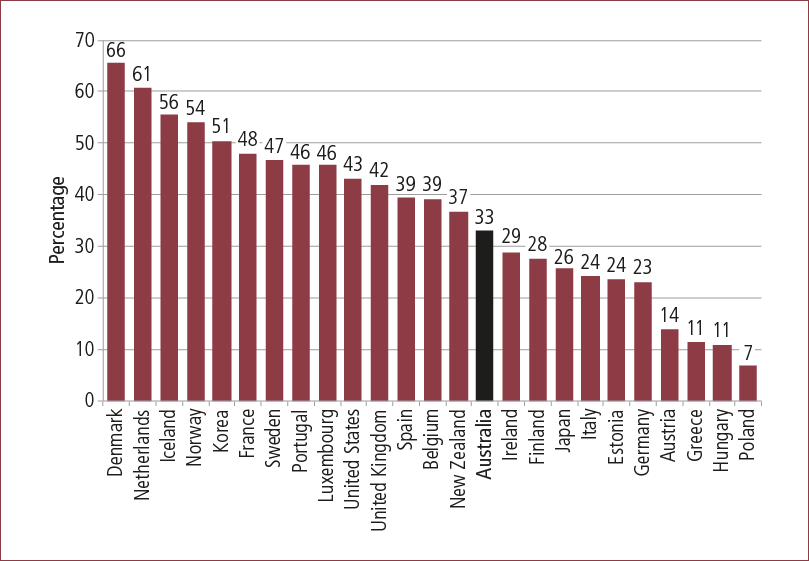

3.2 Paternity leave

Paternity leave is generally made available to fathers in the weeks following the birth of the child, and is sometimes provided as part of parental leave, rather than specifically identified as paternity leave. While not required under EU directives, the majority of EU member countries provide for a minimum of 10 days of paternity leave (Commission of the European Communities, 2008c). Australia has no statutory paternity leave. Some examples of paternity leave policies are shown in Box 3, and a comparison of selected countries with paternity leave is shown in Figure 3.

Box 3: Examples of paternity leave policies

| Canada (& Québec) | No statutory paternity leave in Canada - only in Québec. As with their maternity leave policy, paternity leave in Québec can be taken for a shorter period at a higher rate of pay (for three weeks at up to 75% of their average weekly income, capped), or for a longer period at a lower rate of pay (for 5 weeks at up to 70% of their income, capped) (Doucet, Lero, & Tremblay, 2014). |

|---|---|

| France | Men can access 2 weeks of paternity leave at up to 100% of their earnings (capped in the private sector, although employers can make up the difference), which must be taken within 4 months of a birth (Fagnani et al., 2014). |

| The Netherlands | Fathers are entitled to 2 days of paternity leave, paid in full by the employer, which can be taken within 4 weeks of the birth of a child (den Dulk, 2014). |

| Spain | Employed fathers are entitled to 15 days of paternity leave, paid at 100% of earnings (with a ceiling). In addition, 10 weeks of maternity leave may be transferred to the father in some circumstances (if mothers have taken 6 weeks of maternity leave after the birth, the father fulfils contributory requirements, and the transfer does not endanger the mother's health) (Escobedo & Meil, 2014). |

| Sweden | Fathers can take 10 days of "temporary leave in connection with a child's birth or adoption" within 60 days after the birth. Payment is up to 80% of their earnings, capped. Self-employed fathers are also covered (Duvander, Haas, & Hwang, 2014). |

| United Kingdom | Fathers are eligible for 2 weeks of paternity leave, paid at the flat rate of maternity pay, which must be taken within 55 days of the child's birth (O'Brien et al., 2014). |

Figure 3: Duration of employment-protected paternity leave, paid and unpaid, selected OECD countries, 2013

Note: Includes father quota of parental leave. The entitlement to paid leave is presented as the FRE of the proportion of the duration of paid leave if it were paid at 100% of last earnings. FRE is calculated as duration of leave in weeks ´ payment (as a percentage of average wage earnings) received by the claimant. There are some inconsistencies in calculation across countries. For notes and sources for other countries, refer to OECD Family database, PF2.1 Key characteristics of parental leave systems.

Source: OECD Family database (downloaded August 2014), PF2.1 Key characteristics of parental leave systems

Obligatory paternity leave is rare. In Portugal, fathers are entitled to 20 days of "fathers-only parental leave", which equates to paternity leave. Of this, 10 days are obligatory, including 5 that must be taken immediately after the birth and another 5 that must be taken in the first month after the birth (Wall & Leitão, 2014). In some countries, a portion of maternity leave can be transferred to the father (see in Maternity leave, above). Leave for fathers is also available through parental leave in some of those countries that do not specifically have an entitlement to paternity leave (see below).

In Norway, the purpose of paternity leave is considered to be to assist the mother, and so this leave can be transferred to someone else if the father does not live with the mother (Brandth & Kvande, 2014).

An important aspect of paternity leave is the rate at which it is paid. Men are unlikely to take unpaid paternity leave (Commission of the European Communities, 2008c), but when salary compensation during the period of leave is earnings-related, take-up rates are relatively high (O'Brien et al., 2007). Take-up rates of paternity leave are lower than those of maternity leave, although in several countries (e.g., Denmark, Finland, France, Sweden, the Netherlands and the UK) take-up rates of around two-thirds are reported (Moss, 2014).

3.3 Parental leave

Parental leave is a job-protected absence from work, usually additional to maternity and paternity leave, and has been introduced in the majority of developed countries, although the conditions of this leave vary enormously across countries. This leave has tended to be available to both parents, for one or both to take, although it is taken much more by mothers than by fathers (Moss, 2014). In some countries in more recent years, parental leave entitlements have included a period of time quarantined for use only by the father, to encourage their take-up of the leave (discussed further below). In fact, an emerging trend in relation to leave for parents is for parental leave to subsume maternity leave, but with parental leave including separate amounts of leave that are designated for use by the mother and by the father (Moss, 2014).

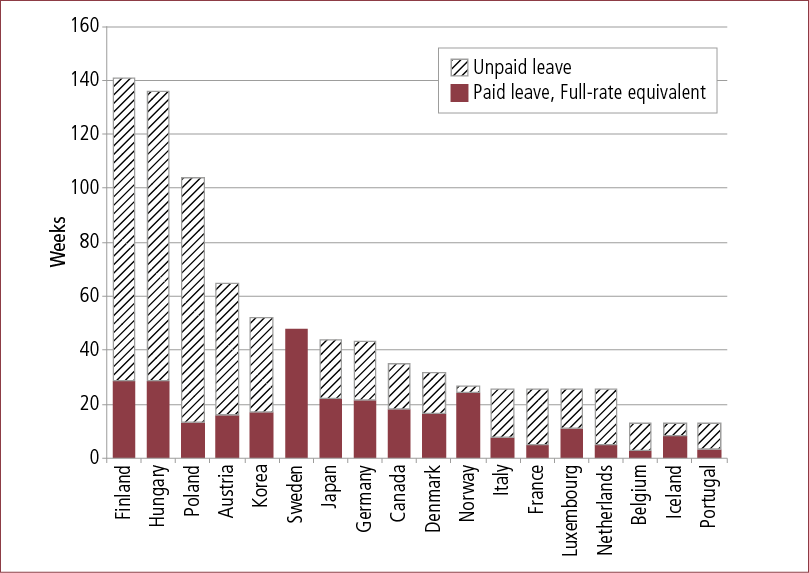

EU countries are bound by the parental leave directives to provide parental leave, with minimum conditions specified relating to time off after the birth, unlawful dismissal during parental leave, and further time off to attend to family emergencies or illness (Ray, 2008). As with maternity leave, there are, however, many differences across EU countries, as there are across all developed countries. Refer to Box 4 for examples and to Figure 4 for comparisons of leave entitlements across selected OECD countries. Below, we elaborate on some of the ways in which parental leave varies across countries.

As at 2014, few developed countries provided no parental leave (Switzerland, South Africa and the US) (see Moss, 2014).

Box 4: Examples of parental leave policies

| Finland | Paid parental leave of 158 working days is available as a family entitlement. The rate of payment is earnings-related and, on average, is 70-75% of their usual earnings (capped), paid through the national insurance system. Leave can be taken part-time only if both parents work part-time and employers agree. Leave can be taken by each parent in two parts of at least 12 days duration (Salmi & Lammi-Taskula, 2014). |

|---|---|

| Germany | Parental leave of 3 years is available as a family entitlement. For the first 12 months, parents are entitled to a "child-rearing benefit" of up to 67% of their average earnings (capped). This payment can be taken at half-pay for 24 months instead. The payment period is extended to 14 months if at least 2 months of the leave is taken by the father. Parents can also combine parental leave with part-time work, with a reduced benefit. The final year of parental leave can be available up to the child's 8th birthday, if the employer agrees (Blum & Erler, 2014; Commission of the European Communities, 2008c). |

| The Netherlands | The amount of leave each parent can take is equal to 26 times the hours they worked before the birth, per child. Leave has to be taken part-time, unless the employer agrees to full-time leave. Leave can be taken up to the child's 8th birthday, in two or three blocks of time, with the agreement of the employer. Parental leave is unpaid, but parents taking parental leave are entitled to a tax reduction. Some parents have access to partially paid parental leave through their employer (den Dulk, 2014). |

| New Zealand | Up to 52 weeks of extended leave can be taken by parents after the birth, including any paid maternity leave taken. Most of the leave, then, is unpaid. Extended leave must be taken in one continuous period in the child's first year, after paid maternity or paternity leave. The leave can be shared by both parents and can be taken simultaneously or consecutively (McDonald, 2014; NZ Department of Labour, 2008a). |

| Sweden | Paid parental leave of 480 days is available per family. Of this, 60 days are quarantined for the mother and 60 days for the father. Half of the remaining days are also reserved for each parent; however, these days can be transferred from one to the other upon the parent giving up his or her days by signing a consent form. Parental leave is paid at up to 78% of their usual earnings (capped) for the first 390 days of leave and at a flat (low) rate for the remaining 90 days (Duvander et al., 2014). (See also Sweden's "gender equality bonus", in Box 5.) |

Figure 4: Duration of employment-protected parental leave, selected OECD countries, 2013

Note: Does not include periods of leave for exclusive use by mothers and fathers and is regardless of income support. Includes subsequent prolonged periods of leave to care for young children (sometimes under a different name, e.g., "child care leave" or "home care leave", or the complément de libre choix d'activité in France). The entitlement to paid leave is presented as the FRE of the proportion of the duration of paid leave if it were paid at 100% of last earnings. FRE is calculated as the duration of leave in weeks ´ payment (as a percentage of average wage earnings) received by the claimant. There are some inconsistencies in calculation across countries. For notes and sources for other countries, refer to OECD Family database, PF2.1 Key characteristics of parental leave systems.

Source: OECD Family database (downloaded August 2014), PF2.1 Key characteristics of parental leave systems

The length and level of remuneration

Many countries provide a year or more of parental leave, although this period of leave is not always paid at full wage replacement for the entire period. While job protection is therefore guaranteed for those who can afford to take a longer absence from work, the financial incentive to remain out of employment will vary depending on what the specific arrangements are. The variation is evident in Figure 4, by looking at the differences in full-rate equivalent paid leave across countries. Compensation during parental leave is dependent on prior earnings in countries such as Finland (70-75% of prior earnings), Germany (67%), Iceland (80%), Sweden (78%) and Italy (30%), although this tends to be capped at a certain level and/or after a certain number of days, beyond which a lower percentage or a fixed rate of payment applies. Parents in Denmark who are employees covered by collective agreements can access parental leave at 100% of their prior earnings, up to a ceiling. Elsewhere, compensation is in the form of a flat-rate payment (e.g., Austria, Belgium, France and Luxembourg), or parents receive financial compensation through the tax system (e.g., the Netherlands and Luxembourg). In other countries, parental leave is unpaid (Greece, Ireland, Spain and the UK; see specific country notes in Moss, 2014, for details).

The flexibility of leave and return-to-work arrangements

It has been suggested that good leave schemes give parents choice in their return-to-work decisions, and allow flexibility in taking leave entitlements (OECD, 2007, p. 21)

The more flexible parental leave models allow parents to share the leave between parents, to take parental leave at any time from the end of maternity leave to some specified age of child (e.g., up to 12 years old in Sweden, and 3 years old in France and Germany), and to combine parental leave with part-time work, as a gradual return-to-work strategy. There have been considerable developments over recent years in these various flexible options.

In recognition that it is difficult to combine full-time work with the care of a young infant, in several countries, as part of the parental leave "package", parents are able to return to work at reduced hours for a specified period. This "gradual return to work" is facilitated through parental leave that can be taken part-time. When this parental leave is paid, the part-time parental leave compensates for the reduced hours at work (or part-time work "tops up" the parental leave). Gradual return-to-work models provide job protection and a right to return to previous working hours. For example:

- Sweden has promoted part-time work in this way (Fagan, 2003) and, indeed, part-time work is most often used this way - for a relatively short period of time after the birth of a child as a transition from leave back to full-time hours (Evans, Lippoldt, & Marianna, 2001). In Sweden, parents have the right to request a reduction in work hours by up to 25%, up until the child's 8th birthday (Duvander et al., 2014).

- In Germany, parents can work part-time while on parental leave (with a right to return to full-time work afterwards), and the third year of parental leave can be taken any time until the child's 8th birthday with the employer's agreement (Blum & Erler, 2014).

The part-time work option may not be available in all jobs, such as those in small businesses. For example, in Germany, access to part-time work is not guaranteed in workplaces of 15 or fewer employees. Further, employers may be able to refuse a request for part-time work if it would detrimentally affect the business or workplace (Hegewisch & Gornick, 2008; OECD, 2010).

As seen in these examples, access to part-time work through parental leave can continue beyond the immediate post-maternity period. In countries such as Sweden, Germany and Finland, this parental leave/part-time work option can be saved up and taken in blocks of time, rather than using it all up before returning to work full-time. Other countries that have similar approaches are Belgium, Estonia and the Netherlands (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014a). Being able to take some of the leave at a later time can lead to a higher take-up of leave by fathers (Hegewisch & Gornick, 2008).

Another flexible approach to parental leave, or to parental leave payments, is the ability for parents to transfer some of this to others (such as grandparents) who are assisting the parents by providing care to children. This is possible, for example, in Estonia and Hungary, and will be discussed when exploring child care provisions in section 4.4.

Eligibility requirements and special conditions to encourage take-up by fathers

One difference across countries is how parental leave entitlement is determined - whether it is per family or per parent - and if a parental entitlement, whether two parents can take parental leave at the same time (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014a). This is most relevant in considering whether or not fathers will take some of the parental leave. While parental leave has, for some years, been available to share between the mother and father in general, fathers still take significantly less time out of employment to help care for children. As stated by the OECD:

taking a few weeks of leave after childbirth or around summer and Christmas holidays does not reflect a fundamental behavioural change. Paternal attitudes are not the only issue, as mothers frequently seem reluctant to give up leave in favour of their partner … The debate about individualisation of the entire paid parental leave entitlement which could contribute to a more equal sharing of care responsibilities has yet to start in earnest. (OECD, 2007, p. 22)

Moss (2008) summarised the key features of fathers' use of leave as, fathers:

- using high paid "fathers only" leave;

- not using low paid or unpaid parental leave;

- not using a "family entitlement" to leave, even if high paid, if there is also a "fathers only" entitlement;

- making only limited use of the "family entitlement" to leave if there is no "fathers only" entitlement, that is, mothers are using most or all of the leave that is a "family entitlement" (pp. 80-81).

As take-up of parental leave has continued to be very low for fathers, various approaches have been developed with the goal of increasing fathers' take-up of leave. Some countries have attempted to increase the role of fathers in providing care by allowing or even requiring that some of the parental leave be used by the father. This has been done, for example, by incorporating a bonus period of leave that can only be accumulated if the father takes his portion of leave (e.g., in Finland, Germany and Italy). These approaches are referred to as "ring-fencing" fathers' leave, or a "use it or lose it" approach (see examples for Iceland and Norway, in Box 5).

Another approach is the availability of bonus payments for families in which the fathers take up leave (e.g., in Sweden; see Box 5). Also, as noted in section 3.1, some countries enable a portion of maternity leave (not just parental leave) to be shared between mothers and fathers.

An important consideration for fathers, and for their families, is that fathers are very often the higher income earner, and it can therefore be very costly for families if this income is reduced due to a period of unpaid, or reduced-pay, leave (O'Brien et al., 2007). Gornick and Meyers (2003) suggested that high wage replacement, along with public education campaigns, may be what is required to encourage fathers to take parental leave.

Box 5: Examples of policies to encourage take-up of leave by fathers

| Finland | Up until the end of 2012, fathers were eligible for 24 bonus days of leave if they tpok the last 2 weeks of parental leave. Together, this was referred to as the "father's month". At 2014, all fathers' leave has been subsumed into paternity leave (Salmi & Lammi-Taskula, 2014). |

|---|---|

| Iceland | Of a total of 9 months of paid parental leave, 3 months are allocated to the mother, 3 months to the father and the remaining 3 months can be taken by either parent (parents' joint rights). Payment of up to 80% of parents' earnings (capped). In 2010, 95% of fathers took some leave, including 17% of fathers who used some of the parents' joint rights. Fathers took about one-third of the total parental leave days (Eydal & Gíslason, 2014). |

| Norway | Up to mid-2014, the total length of parental leave was 46 weeks with 100% wage replacement (capped), or a longer leave with lower payment. Of the 46 weeks, 14 weeks were for the mother and 14 weeks for the father (the father's quota), with the remaining weeks being a shared family entitlement. Previously, the fathers' quota was less and the shared period longer, the change having intended to achieve more equal rights between mothers and fathers in access to leave. However, a new government changed entitlements again, such that from mid-2014, the mothers' and fathers' quotas were to be reduced to 10 weeks and the shared quota increased by 8 weeks. Changes introduced at this time also made it easier to transfer fathers' entitlements to mothers, with the fathers' work situation being a valid justification for such a transfer (Brandth & Kvande, 2014). |

| Sweden | Couples are entitled to a "gender equality bonus" (an additional payment) if they share parental leave equally. The bonus is also available to parents who do not live together (Duvander et al., 2014; Ray, 2008). |

3.4 Return-to-work employment rights

Job protection is a central feature of maternity, paternity and parental leave, such that this leave is sometimes referred to as "job-protected" leave. For example, the 2010 amendments to the EU parental leave directives state: "At the end of parental leave, workers shall have the right to return to the same job or, if that is not possible, to an equivalent or similar job consistent with their employment contract or employment relationship".10

Rights to return to the same, or equivalent, job after returning from leave are usually addressed in relation to these forms of leave. On return to work, some countries offer parents options for varying their working arrangements to better fit within their care requirements. Rights to request variations in hours or flexible work arrangements are discussed in section 5.

3.5 Breastfeeding breaks and facilities