The Stronger Families in Australia (SFIA) Study: Phase 2

September 2014

Ben Edwards, Killian Mullan, Ilan Katz, Daryl Higgins

Download Research report

Overview

This report presents a medium- to long-term evaluation of the Communities for Children (CfC) initiative. This Australian Government initiative aims to improve services for young children and their families and the communities they grow up in. The evaluation, known as the Stronger Families in Australia (SFIA) study, looks at the impact of CfC on child, family, and community outcomes. Phase 1 of the evaluation, published in 2009, found a small but positive impact of the initiative. This new report presents findings from Phase 2 of the study, which followed up 1,927 of the original study families, with the children now aged from 8-10 years old. Phase 2 also introduced a new cohort of 1,800 families and four new "contrast" sites.

Key messages

-

CfC has had some of the desired effects on parents and children, but these were not strong or sustained for long enough to make statistically significant differences over the long term.

-

Over the five waves of SFIA, the vast majority of findings indicated that the wellbeing of children and parents in CfC communities was better than in comparison communities, even if these differences did not reach statistical significance.

-

Very few studies of early intervention services follow children for six years and provide the depth of information that SFIA has been able to deliver.

-

Many other studies of early intervention services have also failed to find sustained positive effects over the longer term (e.g., NESS Team, 2012).

-

Whether another model, a more intensive version of CfC or a set of evidence-based interventions would have had a greater effect is not known.

Executive summary

This report presents the results of Phase 2 of the Stronger Families in Australia (SFIA) study, an evaluation of the Communities for Children (CfC) initiative. The focus is on examining the effects of the initiative on child, family and community outcomes. By using data from Phase 1 (Waves 1 to 3 conducted from 2006-08) and Phase 2 (Waves 4 and 5 conducted in 2010-12) of the Stronger Families in Australia (SFIA) study, the medium- to longer-term effects of the program can be assessed.

As is outlined in detail in the report: Stronger Families in Australia Study: The Impact of Communities for Children (Edwards et al., 2009), the CfC initiative aimed to:

- improve the coordination of services for children 0-5 years of age and their families;

- identify and provide services to address unmet needs;

- build community capacity to engage in service delivery; and

- improve the community context in which children grow up.

As part of the CfC initiative, the Department of Social Services (DSS; formerly Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs [FaHCSIA]) funded non-government organisations as "Facilitating Partners" initially in 45 disadvantaged geographic areas around Australia. Their task was to develop and implement a "whole-of-community" approach to enhancing early childhood development, through consultation with local stakeholders. The idea behind the CfC model is that service effectiveness is dependent not only on the nature and number of services, but also on coordinated service delivery. The types of services offered in the CfC sites differ depending on the needs of each community, and include home visiting; programs on early learning, child nutrition and literacy; parenting and family support services; and community events (Edwards et al., 2011). There are now 52 funded CfC Facilitating Partners.

In 2009, CfC services were incorporated into the Family Support Program, which brought together a wide range of services for children and families, broadening their scope to include services for children aged 0 to 12 years and targeting vulnerable and disadvantaged families. In the same year, eight sites were targeted to focus on preventing child abuse and neglect in particular - four were existing CfC sites and four were new sites. In this report, these sites are referred to as Stage 2 CfC sites. Stage 2 CfC sites have not been included in the CfC evaluation reported in the main body of this report; however, preliminary waves of data from the early implementation of seven Stage 2 CfC sites and comparison (contrast) sites are included in the appendix.

As in the initial phase of the evaluation, Phase 2 of the SFIA study provides a unique opportunity to consider the effectiveness of the CfC initiative. The strengths of the SFIA study include having a large sample representing 42% of the initial target population in the selected CfC and contrast sites, relatively low and non-systematic attrition from Wave 2 (when children were 2-3 years of age) to Wave 5 (when children were 9-10 years of age), robust measurements of child and family outcomes, and an appropriately matched comparison group. However, the SFIA survey cannot identify the extent to which particular children or families have received CfC services, as one of the key features of the initiative was to change the nature of how the service delivery system operates in a community context.

Summaries of the key findings of the study and some of the implications of these findings are provided below.

Summary of evaluation findings

Effects of CfC initiative on child, family and community outcomes in Stage 1 CfC sites

To date, findings from the evaluation of Stage 1 CfC sites suggest that there were some positive effects of the program on a variety of outcomes during Phase 1, although some faded out when children started school (Phase 2). The positive effects of the CfC initiative included:

- a reduction in jobless households from Wave 1 to Wave 3, but not in later waves;

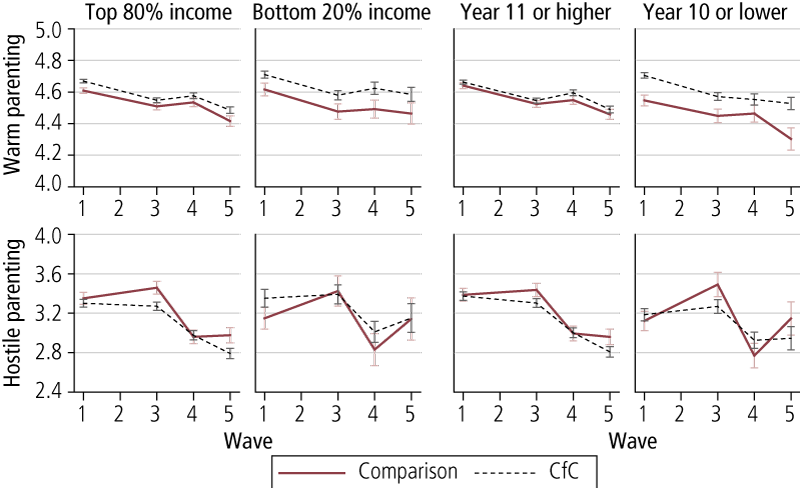

- reductions in primary-carer-reported hostile or harsh parenting practices (from Wave 1 to Wave 3 only), and at Wave 3 and Wave 5, lower levels of harsh parenting practices at Wave 3 and Wave 5;

- primary carers feeling more effective in their role as parent (at Wave 3 only);

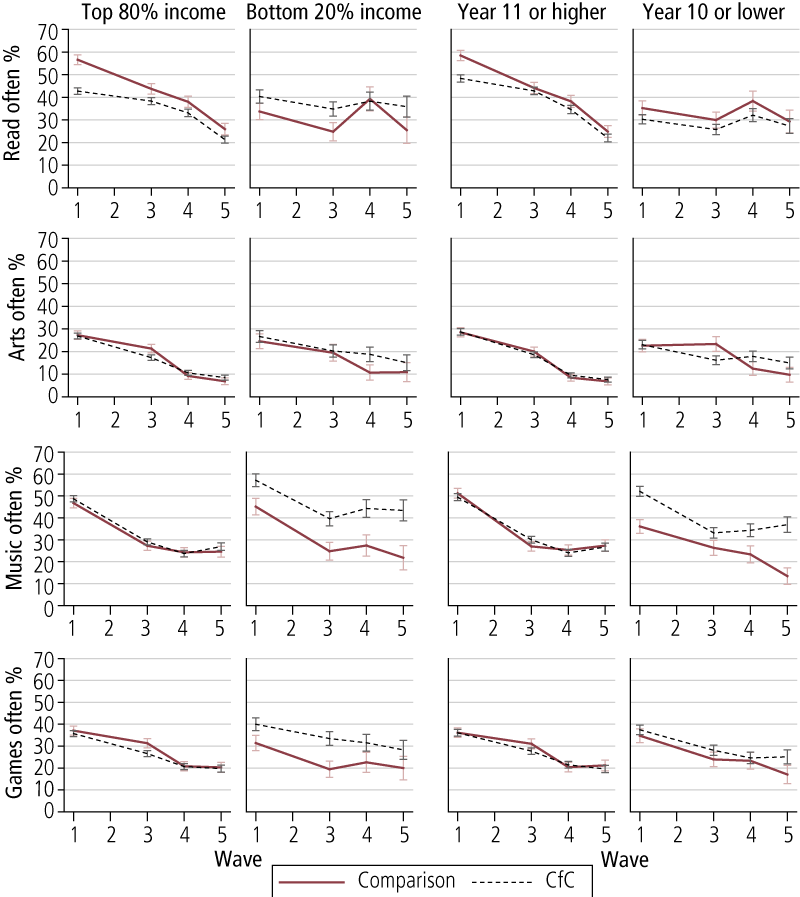

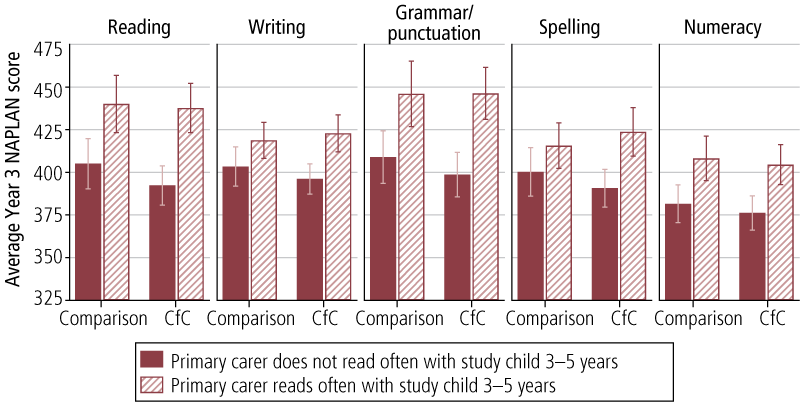

- greater improvements in reading often to the target child between Waves 1 and 3 and Waves 1 and 5 compared to those living in comparison sites, with these gains largely being reflected in benefits to children living in families that were relatively more advantaged (particularly higher income families);

- greater engagement with children in music and singing among primary carers from more disadvantaged families (with lower income and education) between Wave 1 and 5; and

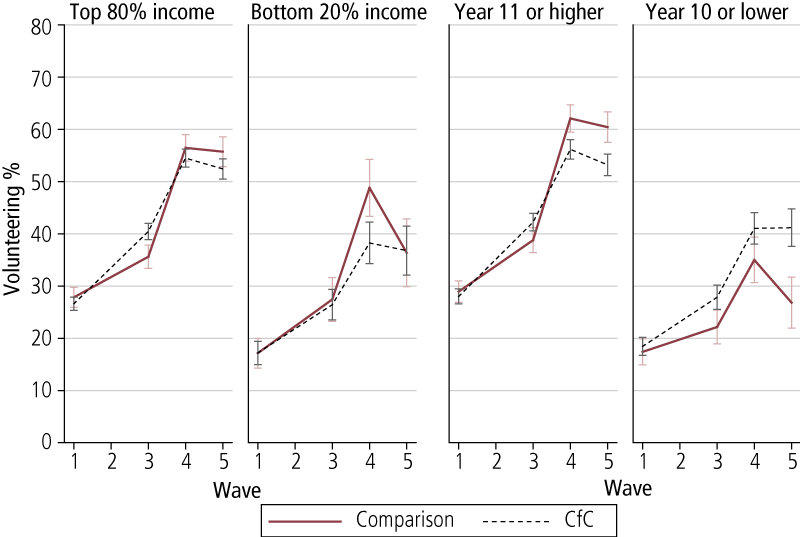

- greater volunteering by primary carers between Waves 1 and 3 overall, and evidence of greater engagement in volunteering between Waves 1 and 5 for primary carers with lower levels of education.

There were several other noteworthy results that were less conclusive:

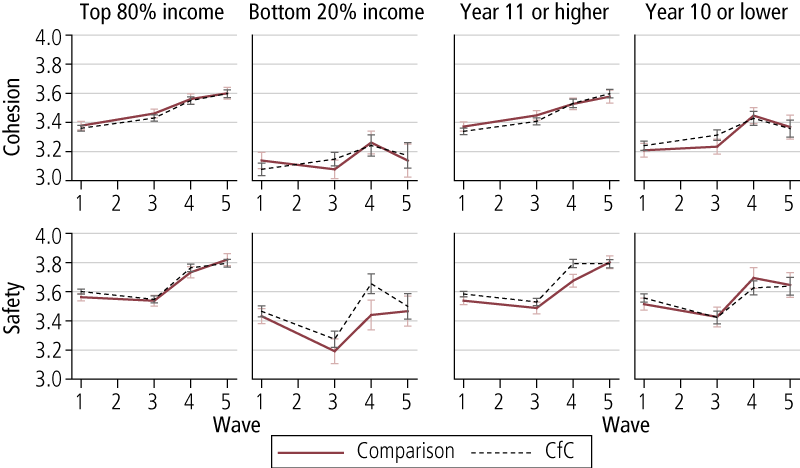

- Overall, CfC had little effect on neighbourhood social cohesion and community safety, but there were some improvements for families in the lower income group.

- In Phase 1 of the evaluation, primary carers reported that children's physical functioning worsened in CfC compared to comparison sites between Wave 1 and Wave 3 but this was no longer the case in Waves 4 and 5.

- There were two instances that were likely to indicate pre-existing differences at baseline and are not indicative of a program effect. Namely, when primary carers' mental and physical health improved over time in comparison sites for the lower educated subgroup, compared with CfC sites, which remained the same over time. Although this might suggest worse outcomes in CfC sites, it is more likely to reflect comparison sites "catching up", given that parents in comparison sites reported lower levels of physical and mental health than parents in CfC sites in Wave 1.

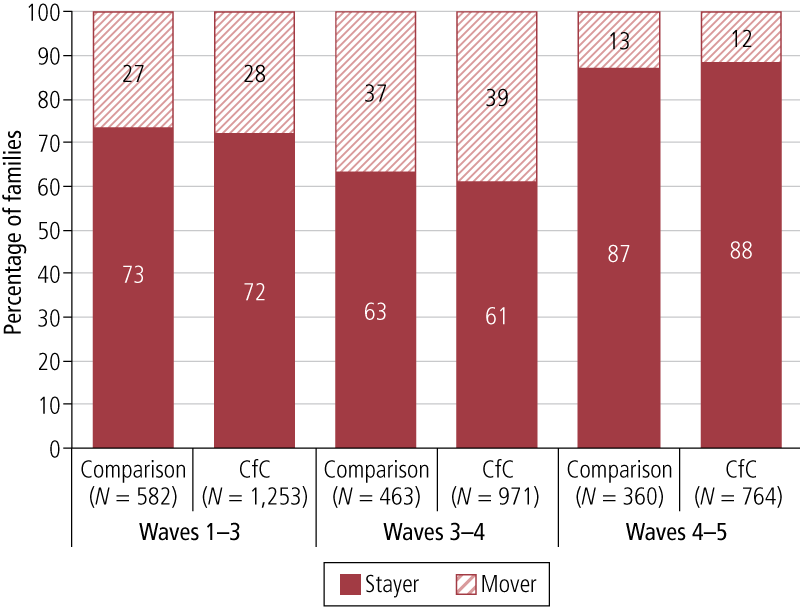

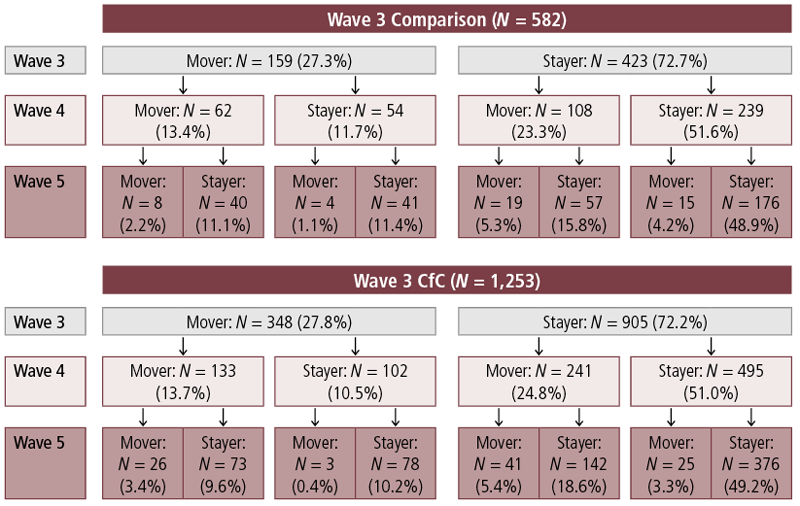

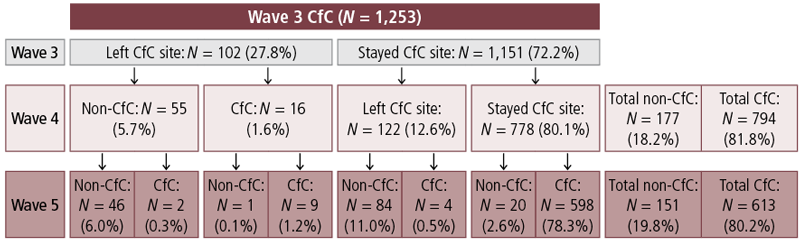

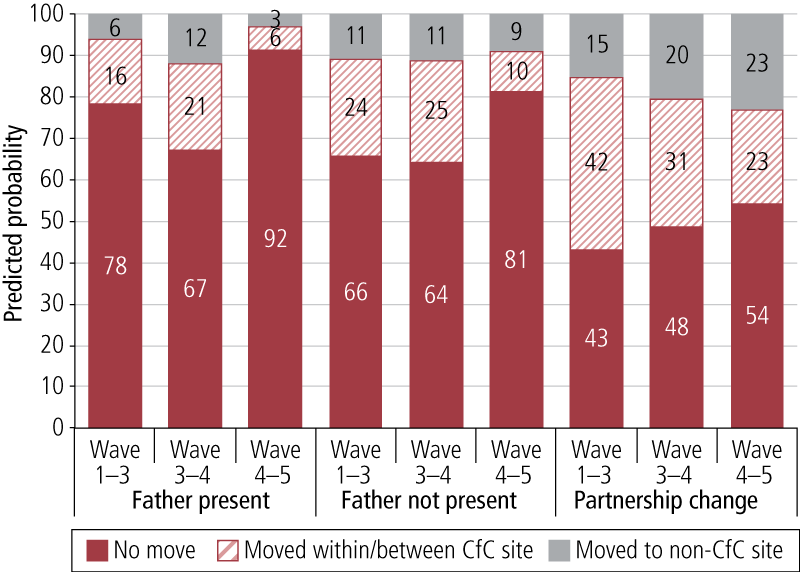

Residential mobility and out-migration from CfC sites

While all families in the intervention group lived in CfC sites at Wave 1 of the survey, many may have moved out of a CfC site in subsequent waves. Measuring any change in subsequent waves is important because:

- there was a need to establish that the findings from the Stage 1 CfC sites were robust to residential mobility; and

- the extent to which individuals move out of areas that are targeted for area-based initiatives is largely unknown.

In general, there was no evidence to suggest that residential mobility biased the findings of the overall evaluation. Key findings on residential mobility and out-migration from CfC sites were that:

- one in two families living in CfC sites when their children were 2-3 years of age were still living in a CfC site seven years later; and

- these rates are consistent with that of the general population (Edwards, 2011).

Links between program effects and child outcomes

There were significant program effects in Stage 1 CfC sites relating to family joblessness, the engagement of primary carers in children's reading and the community involvement of primary carers, particularly at Wave 3 and at later ages for subgroups. Given that other studies (Coelli, 2005; Huttenlocher, Haight, Bryk, Seltzer, & Lyons, 1991; Kalil & Ziol-Guest, 2008; Senechal, LeFevre, Hudson, & Lawson, 1996) have found that these outcomes are likely to be beneficial to children's development in the longer term, we wanted to examine whether there were flow-on benefits to children when they were in their primary school years.

To consider this, we explored associations between family joblessness, the engagement of primary carers in children's reading, and the community involvement of primary carers and:

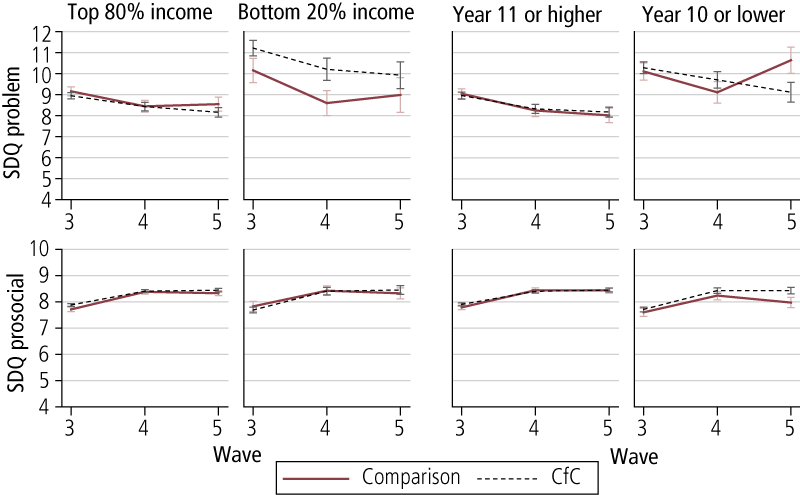

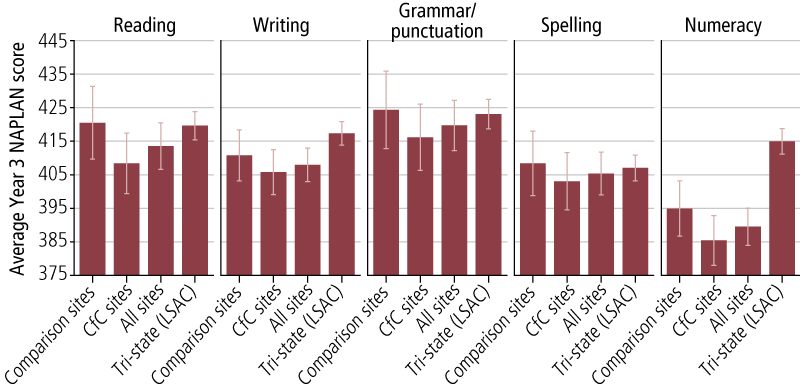

- NAPLAN (the National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy) scores relating to children's reading, writing, grammar and punctuation, spelling and numeracy at Year 3 of primary school; and

- children's social and emotional wellbeing measured at 3-5, 8-9 and 9-10 years of age.

The overall conclusion from this analysis was that there were many instances where family joblessness, parents reading to their children and the community involvement of primary carers were associated with later literacy/numeracy and social/behavioural outcomes for children in the CfC and comparison sites. More specifically:

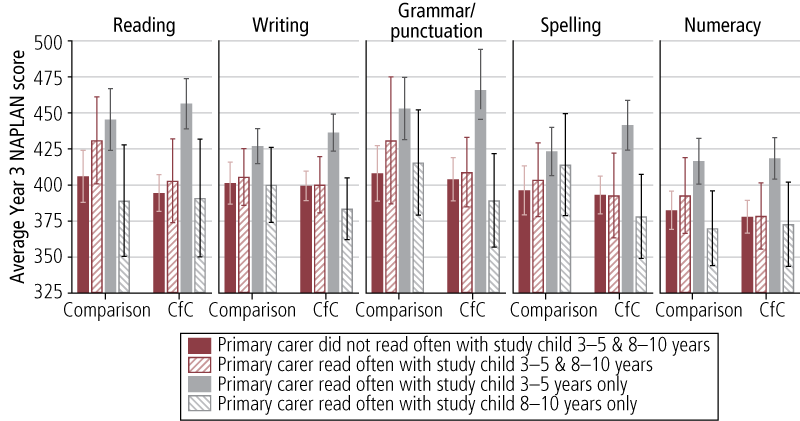

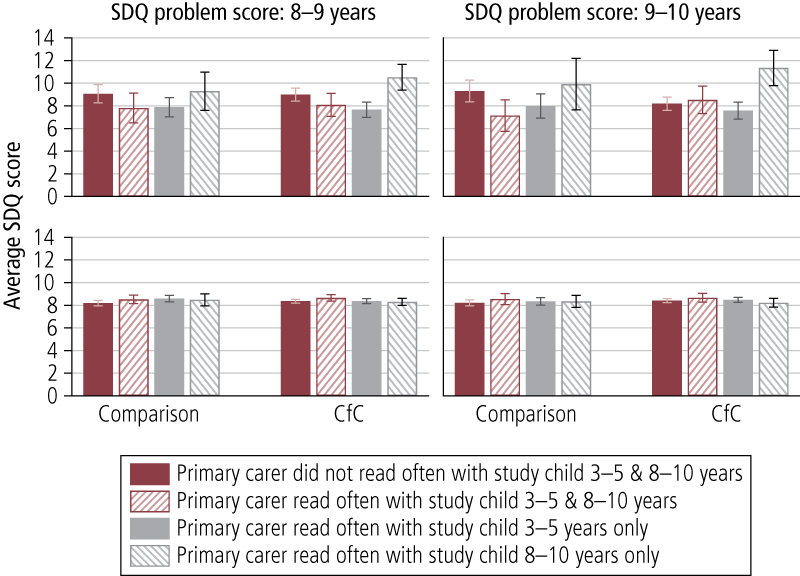

- Primary carers reading often with children at 3-5 years was consistently associated with improved literacy and numeracy scores from NAPLAN tests, but not with increased reading scores at later ages.

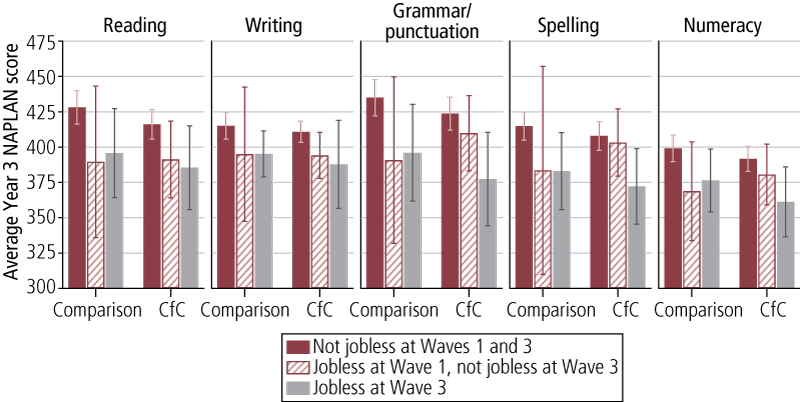

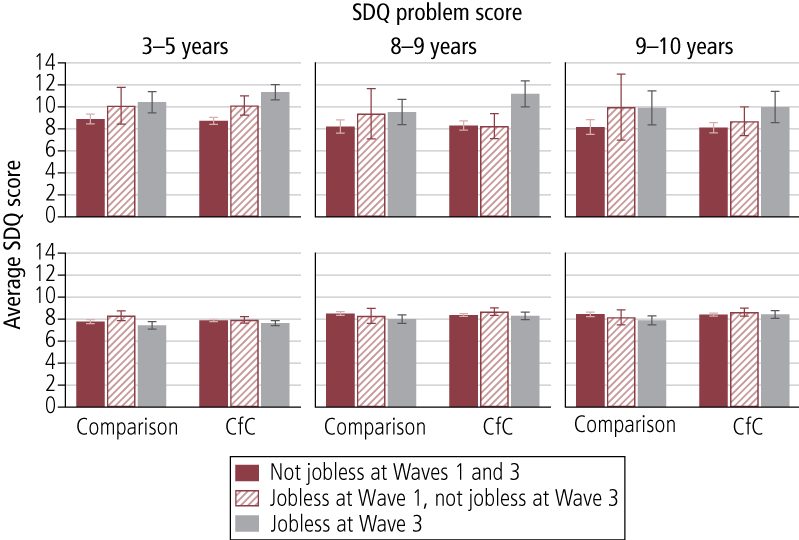

- Family joblessness when children were 4-5 years of age was associated with lower literacy and numeracy skills and poorer social and emotional behaviour in children aged 8-10 years.

- Family joblessness prior to children entering school was associated with poor early literacy, which later undermined learning in primary school.

- In families that had moved out of family joblessness by the time their children were 4-5 years of age, the negative effects of joblessness on literacy/numeracy and social/behavioural outcomes in children were not apparent at 8-10 years.

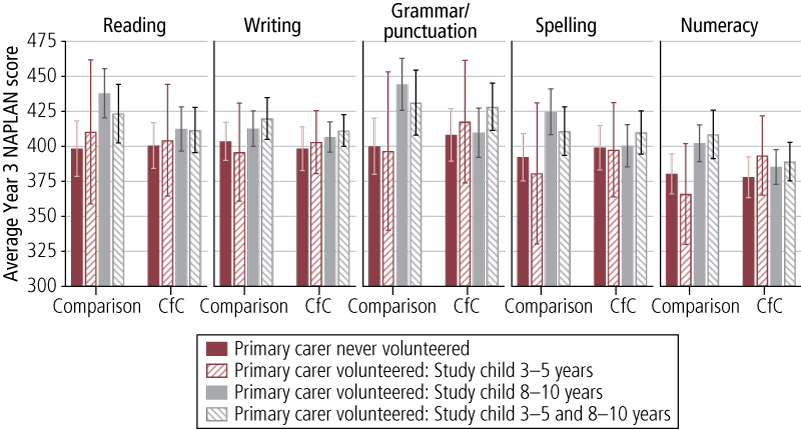

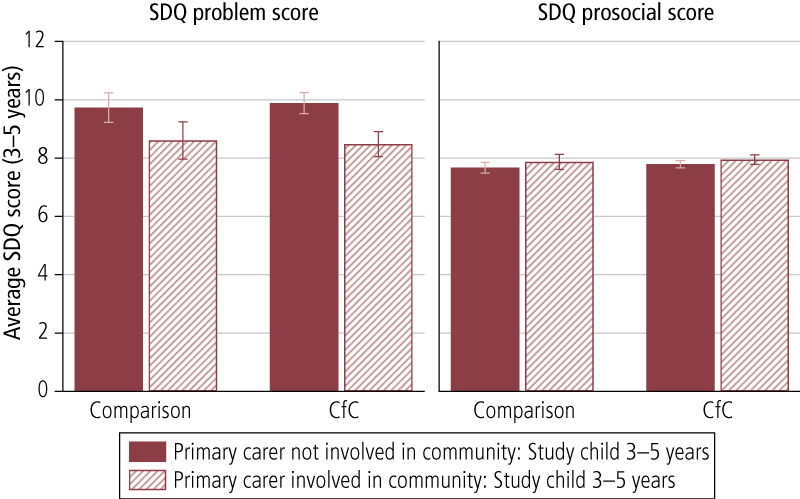

- Consistent volunteering by primary carers when children were aged 4-5 years and 8-9 years of age was associated with lower levels of social and behavioural problems in children.

- There were no statistically significant differences between CfC and comparison sites on any of the NAPLAN scores.

Timing of the CfC initiative effects: interpreting the implications

Although there were a number of positive (and a few negative) effects of the CfC initiative, most were not durable and faded out by the time children started school. It is important to recognise that this pattern of findings is not unexpected or unique in area-based initiatives. The National Evaluation of Sure Start (NESS) in the UK reported similar findings (NESS Team, 2012), with positive findings in children's outcomes observed when children were 5 years of age no longer evident when children were aged 7 years and in primary school.

With respect to interpreting the results for volunteering, normative data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) suggest that parents increase their rates of volunteering once their child starts school. Our results certainly reflect this normative increase.

One of the key findings from Phase 1 of the evaluation was that there was a reduction in jobless families in CfC compared to comparison sites. Phase 2 results suggest that comparison sites caught up to CfC sites in terms of the percentage of jobless families by the time children were 8-10 years of age. The same pattern of results was also observed in the Sure Start initiative (NESS, 2012), where there was a reduction in the rate of joblessness for Sure Start sites compared to comparison sites when children were aged 9 months to 5 years. There are two possible reasons why this may have occurred in the CfC sites:

- when children are at school, primary carers have more time to go to work and have much lower child-care costs; and

- over 2006-08, welfare-to-work reforms required parents on income support (single and partnered) to actively seek part-time work, with these changes being put in place after Wave 3 but before Wave 4 of the SFIA survey.

It may also be that once a certain "floor" is reached, it is very difficult to further reduce joblessness, even with a combination of the CfC initiative and welfare-to-work requirements.a

Effects on later child wellbeing of early vs late reading, volunteering and moving out of joblessness

We have seen positive early results relating to primary carers reading to children, primary carers volunteering and family joblessness. Given that there is some evidence that both children starting school and the introduction of the welfare-to-work reforms may have enabled families in comparison sites to catch up to families in CfC sites, it is important to consider whether these early positive effects in the families of young children would have demonstrable benefits in the longer term for families in both CfC and comparison sites. In Chapter 6 we explore this issue by examining whether children benefitted in the early primary school years in the areas of literacy, numeracy, social and behavioural outcomes if they were often read to at age 3-5 years, had a primary carer who consistently volunteered and had a family that moved out of joblessness.

It is important to note that we were examining whether associations between these variables and child outcomes mattered, not whether there was a treatment effect of CfC on children's outcomes.

One of the key findings with respect to these rather disparate factors was that timing seemed to matter. Engagement in reading, volunteering and moving out of family joblessness were all associated with positive benefits to children's outcomes for those in CfC and comparison sites. We also saw some evidence to suggest that there were detrimental effects of joblessness prior to starting school, when children were 4-5 years of age, as the influence of joblessness on later NAPLAN scores was mediated through differences in early literacy skills at 4-5 years that were associated with concurrent family joblessness. Therefore, school readiness and what happens prior to school entry is also an important consideration. Findings from this set of analyses seem to suggest the timing of when we observe the beneficial effects of CfC matters for children's development is important.

Caveats for translating evaluation findings into policy

Before commenting on the implications of these findings for policy development, it is important to note some of the limitations and caveats. These include:

- The size of the CfC effects was small, but comparable in size and timing to the UK Sure Start evaluation. Other reviews of the effectiveness of early childhood interventions have also suggested the majority of effects on parenting and child outcomes were small (Wise, da Silva, Webster, & Sanson, 2005; except for Triple P which reported greater effects).

- The CfC initiative encouraged heterogeneous service delivery operating in each site, and therefore families from each site may have received services focused on different aspects of the outcomes that were examined. Thus, not all the CfC sites would have had a consistent set of services targeting each particular outcome in the evaluation and perhaps this explains why, while there was a general trend towards positive effects in many outcomes, only a few were statistically significant.

- As far as we are aware, the CfC services were not required to meet a certain standard of service delivery as part of the initiative. Therefore, the quality of program delivery was not assessed and cannot be ascertained by the evaluation.

- Site-by-site analysis of outcomes was not possible because of the small number of sites in the CfC and contrast sites examined.

- SFIA sites were not randomly chosen from CfC sites (although they are broadly representative of the range of CfC sites, outside of remote communities).

- The nature of SFIA (and the logic model of CfC) meant that the evaluation was not able to link outcomes with exposure to CfC-funded services. Children and primary carers in the SFIA cohort are a random sample of the population in the CfC community. It is not known therefore whether these families had had contact with CfC services and if so, how much contact they had had.

- The evaluation did not compare CfC (as it then was) with other models of service delivery. The contrast sites were demographically similar to CfC communities, but did not receive CfC funding. Therefore, CfC was not compared to other models, such as direct funding of non-government organisations (NGOs), programs that are not area-based, or programs funded through state and territory sources or interventions not specifically aimed at children in their early years and their parents.

- Finally, it is important to note that the outcomes measured point to aspects of parenting and child development that are difficult to measure accurately. We have used well-validated measures, but there is always error in measurements that can affect the efficacy of any statistical analysis.

Implications

What are the advantages of area-based initiatives?

- SFIA does not provide any direct evidence of the potential effects of place-based initiatives compared to individually targeted interventions.

- However, there were clear advantages of a place-based approach in the early years, as around the time of implementation, there were significant service gaps, and few mechanisms to coordinate early years services.

- The advantages for older age groups are less clear.

Would a more targeted/evidence-based approach produce better outcomes?

- SFIA did not compare community-level outcomes for CfC and targeted services, and so cannot answer this question directly.

- While some evidence-based interventions can have a significant and lasting effect on outcomes (see Chapter 2), the effects apply to people who received the service and not for the community as a whole.

- To our knowledge, none of the targeted programs have followed up families in the general community, and certainly not over six years.

- Targeted programs tend to be much more expensive than CfC.

- The evaluation of CfC found that it was challenging to engage and retain the most hard-to-reach families in the communities, but the area-based approach of CfC was effective in this respect.

- Thus, we would tentatively conclude that the most effective approach would be to provide evidence-based interventions within the context of a community-level intervention.

What are the implications of extending the age range of CfC from 0-5 years to 0-12 years?

Another potential explanation for the effects observed was that in Phase 1 of the evaluation the CfC initiative was funded to focus on 0-5 year olds. In 2009, the focus of CfC expanded to include 6-12 year olds. It was beyond the scope of the evaluation to examine how the service delivery system changed as a result of the 2009 expansion, but given that the financial resources were not increased substantially in line with the increased focus, it is possible that there was not a commensurate expansion in the focus on services for 6-12 year olds.

There is little data on how CfC affected the various services for 6-12 year olds, for example:

- services provided by large institutional providers (schools, medical services, etc.); and

- no information about whether the Facilitating Partner model was able to successfully engage schools, GPs and other statutory providers as early years service providers.

If school-entry and school-based services overcame most of the deficits in the contrast sites, then the implication would be that policy should focus more on improving school provision and school-based services than on services targeted at the early years. On the other hand, the analysis showed that primary carers reading to their children and volunteering and returning to the workforce early in their children's lives had more influence on children's later wellbeing than reading and volunteering when the children were older.

On balance, therefore, the findings indicate that early years interventions are likely to be more effective than interventions when children are already at school.

Conclusion

Key points:

- CfC has had some of the desired effects on parents and children, but these were not strong or sustained for long enough to make statistically significant differences over the long term.

- Over the five waves of SFIA, the vast majority of findings indicated that the wellbeing of children and parents in CfC communities was better than in comparison communities, even if these differences did not reach statistical significance.

- Very few studies of early intervention services follow children for six years and provide the depth of information that SFIA has been able to deliver.

- Many other studies of early intervention services have also failed to find sustained positive effects over the longer term (e.g., NESS Team, 2012).

- Whether another model, a more intensive version of CfC or a set of evidence-based interventions would have had a greater effect is not known.

a This is not to say that other policies (family-friendly employment initiatives, skills training, etc.) may not further reduce rates of joblessness.

1. Introduction

This report presents the results of Phase 2 of the Stronger Families in Australia (SFIA) study, which is an evaluation of the Communities for Children (CfC) initiative. The focus is on examining the effects of the initiative on child, family and community outcomes. By using data from both phases of the SFIA study (Waves 1 to 5, conducted from 2006 to 2012), the medium- to longer term effects of the program can be assessed.

As in the initial phase of the evaluation, Phase 2 of the SFIA study (2010-12) provides a unique opportunity to consider the effectiveness of the CfC initiative. The strengths of the SFIA study include having a large sample representing 42% of the initial target population in the selected CfC and contrast sites, relatively low and non-systematic attrition from Wave 2 (when children were 2-3 years of age) to Wave 5 (when children were 9-10 years of age), robust measurements of child and family outcomes, and an appropriately matched comparison group. However, the SFIA survey cannot identify the extent to which particular children or families have received CfC services, as one of the key features of the initiative was to change the nature of how the service delivery system operates.

Following this introductory chapter, Chapter 2 describes the methodology of the report; Chapter 3 contains the results of the evaluation; Chapter 4 provides a description of residential mobility and considers the implications of this for the main results of the evaluation; Chapter 5 considers associations between some of the early impacts of the CfC initiative on later child outcomes; and Chapter 6 provides some discussion and conclusions. Finally, the Appendix provides an overview of early results from the Stage 2 CfC sites.

1.1 Communities for Children and other area-based initiatives

Communities for Children (CfC) is a large-scale area-based initiative that aims to enhance the development of children living in disadvantaged community areas across Australia. As part of the CfC initiative, the Department of Social Services (DSS; formerly Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs [FaHCSIA]) has funded non-government organisations (NGOs) as "Facilitating Partners" in 45 disadvantaged geographic areas around Australia. Their task is to develop and implement a "whole-of-community" approach to enhancing early childhood development, through consultation with local stakeholders. The idea behind the CfC model is that service effectiveness is dependent not only on the nature and number of services, but also on coordinated service delivery. In each CfC site, the Facilitating Partner conducts a "needs analysis" to decide upon the required services for that community. The Facilitating Partner then engages, coordinates and funds local service providers to deliver the needed services. The types of services provided as part of the CfC initiative include: home visiting; programs on child nutrition, early learning and literacy; parenting and family support services; and community events (Edwards et al., 2011).

The CfC initiative has thus implemented four new service delivery innovations for young children and their families residing in areas of disadvantage (Edwards et al., 2009):

- improve the coordination of services for children 0-5 years of age and their families;

- identify and provide services to address unmet needs;

- build community capacity to engage in service delivery; and

- improve the community context in which children grow up.

1.1.1 Brief history of the CfC initiative

The evolution of the CfC initiative began in 2008, when the Australian Government commenced a strategy of widespread reform of children, families and communities grant programs to more comprehensively support families and build socially inclusive communities. In 2009, the CfC initiative was incorporated into the Australian Government's Family Support Program, bringing together a wide range of services for children and families. At the same time, CfC services were required to widen their scope to include services for children aged 0-12 years and to target vulnerable and disadvantaged families.

In 2009, the CfC initiative was expanded in response to the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009-2020 (Council of Australian Governments [COAG], 2009). The Australian Government and state/territory governments together identified eight communities where targeted and integrated service delivery was needed in order to help prevent child abuse and neglect. This was part of a broader recognition, from a public health perspective, that in order to reduce the number of notifications of concerns about child safety to state/territory statutory authorities, investment is needed in more than just primary (universal) services that support all families. In particular, it is important to increase the capacity of the secondary system to work with families in need where children might be at risk of abuse or neglect, and require a range of family and community supports to ensure children grow up safe and well (Higgins, 2011). Funding was provided under the first Action Plan of the National Framework to address child protection concerns in these eight locations. They included four existing CfC sites and four locations where new CfC services had been established. In this report, these sites are referred to as Stage 2 CfC sites. Stage 2 CfC sites specifically aim to address the risk factors for child abuse and neglect before they escalate, and to help parents of children at risk to provide a safe, happy and healthy life for their children.

In July 2011, the Family Support Program was further streamlined into its current structure. Under the new structure, CfC encompasses a broad range of children's and family services. Area-based services delivered under a Facilitating Partner model are known as the CfC Facilitating Partner program. Other services are known as CfC Direct services. From July 2011, all CfC Facilitating Partners were expected to provide services to prevent child abuse or neglect.

Stage 2 CfC sites have not been included in the CfC evaluation reported in the main body of this report; however, preliminary waves of data from the early implementation of seven Stage 2 CfC sites and comparison sites are included in the appendix.

1.1.2 Evidence base for area-based initiatives

The evidence base for programs such as CfC comes from the wealth of literature indicating that local communities have an important influence on child and family wellbeing. Depending on their availability and quality, community services can provide essential support for families and affect critical child-related outcomes, such as cognitive development and educational achievement (Crane, 1991; Harding, 2004), emotional/psychological wellbeing (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996), and physical health (Morland, Wing, Diez-Rouz, & Poole, 2002; Winkleby & Cubbin, 2003).

Previous studies have also indicated that living in a more disadvantaged area can have a negative effect on children's development and wellbeing, over and above any differences in family characteristics (Burdick-Will et al., 2011; Edwards, 2005; Edwards & Bromfield, 2009). This is a primary reason behind area-based models of service delivery coming into effect within the last two decades (Bloom, 2005; Harding, 2004). The Sure Start Local Programmes (SSLPs) in the UK are a prime example of this, and the evaluation of that initiative provides insights that may be helpful when considering the evaluation of the CfC initiative.

1.1.3 Sure Start Local Programmes: A UK area-based intervention

The SSLPs initiative in the UK is one of the largest area-based initiatives currently in operation. Sure Start was launched in 1999, with its ultimate goal being to enhance the life opportunities for young children growing up in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, due to their higher risk of doing poorly at school, having trouble with peers and authority figures, and ultimately experiencing compromised life chances. As with CfC, there is a specific focus on low socio-economic areas, with all children under five years of age and their families within these prescribed areas serving as the intervention "targets". In addition, similar to CfC, SSLPs do not have a prescribed set of services, with each SSLP having a degree of autonomy over the service delivery in its area, despite the SSLPs coming under the control of Local Authorities in 2005-06 and beginning to operate as children's centres (National Evaluation of Sure Start [NESS] Team, 2010).

Early findings from NESS were somewhat inconclusive, with both positive and adverse effects detected for the disadvantaged families living in the SSLP areas (NESS Team, 2005). Results from the second stage of the evaluation, when the study children were 3 years old, were far more positive, however, with no adverse effects observed. More specifically, children in SSLP areas were more likely to be immunised, were less likely to have accidents requiring treatment, and reported significantly higher levels of positive social behaviour and independence/self-regulation (NESS Team, 2008).

The third stage of the evaluation, reported in 2010, indicated effects that were predominantly positive and beneficial in nature for the 5-year-old study children and their families. The main effects identified for the SSLP children were that they had lower body mass index (BMI) scores and experienced better physical health than the children in the non-SSLP (comparison) areas. Secondly, in regards to maternal wellbeing and family function, it was found that, in comparison to the non-SSLP areas, mothers residing in SSLP areas provided a more cognitively stimulating and less chaotic home learning environment for their children, and also reported having greater life satisfaction and engaging in less harsh discipline. On the negative side, however, mothers in SSLP areas reported more depressive symptoms, and the parents in SSLP areas were slightly less likely to visit their child's school for parent-teacher meetings or other arranged visits, compared to those in non-SSLP areas (NESS Team, 2010).

Overall, results from the third stage of the NESS generally supported the notion that the program's area-based approach had paid off and benefitted children and families in the disadvantaged SSLP sites. However, while there were more positive than negative effects found, there were also many non-significant findings, and hence, the degree of benefit was (at that stage) relatively modest. Evaluators suggested placing greater emphasis on services that improved child outcomes, particularly language development, to enhance school readiness for the SSLP children (NESS Team, 2010).

The fourth stage of the evaluation provided an indication of the effects of the SSLP for school-aged children and whether exposure was associated with longer-term benefits. Some beneficial effects of Sure Start were found for 7-year-old study children and their families (NESS Team, 2012). Of the 15 outcomes that were investigated, there were two positive outcomes across all those living in SSLP areas compared to non-SSLPs. Mothers were engaging in less harsh discipline and providing a more stimulating home learning environment for their children. In addition, there was also a trend towards improved maternal mental health. Also, home environments were rated as less chaotic in SSLP families than non-SSLP families for boys, but there was no difference for girls. Mothers in lone-parent and jobless households also reported better life satisfaction when living in SSLP areas than non-SSLP areas. These findings were based on cross-sectional analyses with sophisticated statistical methodology to control for measured differences between families living in SSLP and non-SSLP areas. The analyses that focused on the eight outcome measures that were repeatedly measured when the children were between 3 and 7 years suggest that mothers living in SSLP areas reported greater decreases in harsh discipline and improvement in the home learning environment than mothers in non-SSLP areas. Mothers living in SSLPs who were lone parents and in jobless households showed greater improvements in life satisfaction compared to their counterparts not living in SSLP areas.

Although the authors concluded that Sure Start had provided some modest benefits relating to disadvantaged mothers' parenting skills, they found no program effects relating to their 7-year-old children's outcomes. They noted that one of the possible explanations for the limited longer-term benefits to children could be due to their access to universal education (NESS Team, 2012). Previously there had been some benefits to children at age 3, but at ages 5 and 7 these were no longer evident. Since 2004, there has been free part-time preschool available in the United Kingdom to every child from age 3 years, and thus 95% of UK children had engaged in preschool during the evaluation period. The authors also noted that by age 7 years, children had been in primary school for three years and therefore the influence of early childhood education and care (ECEC) and primary school may have served to equalise the developmental advantage of children living in SSLP areas. In addition, parental support is a focus of SSLP areas; therefore, an improvement in mothers but not children's outcomes might be expected. While the beneficial effects of parenting and home learning may translate into positive child outcomes in the longer term (as has been observed in home visiting; see Olds et al., 1999), further follow-up into later primary and secondary school and early adulthood will be required to confirm that this does occur. In summary, the findings from the fourth stage of the NESS found limited benefits of SSLPs, and these were to mothers and not to children.

1.2 Key findings from Phase 1 of Stronger Families in Australia

Phase 1 of the SFIA study included data collection waves in 2006, 2007 and 2008 when the study children were aged 2-3, 3-4 and 4-5 years. The purpose of the Phase 1 evaluation was to measure the "short-run" or initial effects of the CfC program across 10 CfC Stage 1 sites and five comparison sites (see section 2.2 for more information about site selection). The evaluation measured whether the CfC initiative had an effect on a range of outcomes it was designed to improve, including families' experiences of local services, primary carers' perceptions of community cohesion, parenting quality, child wellbeing, and the wellbeing of families as a whole (Edwards et al., 2009).

An at-home interview methodology was employed for the three waves of Phase 1, with Wave 1 occurring during the consultation and partnership-building stage of the CfC initiative, and therefore providing baseline data. Wave 2 followed up families around 9 to 10 months after Wave 1, with CfC services commencing either shortly before or shortly after this wave. Finally, the study collected Wave 3 data approximately 11 months after Wave 2 commencement and CfC implementation, meaning that only very short-term effects could be measured by the Phase 1 evaluation (Edwards et al., 2009).

The interviews were conducted with the person in the family who knew most about the child (the primary carer). In most cases, this was the mother. In the remaining cases, the primary carer was the child's resident father, a relative who was the primary carer for the child or a foster parent.

The broad conclusion drawn from Phase 1 of the SFIA study was that the CfC initiative had a small but positive effect on parenting outcomes (i.e., less harsh parenting and higher levels of parenting confidence), the number of jobless households, and children's receptive vocabulary.1 In addition, there was some evidence of a negative effect on the mental health of primary carers with a lower level of education (defined as Year 10 or less), and poorer general health of primary carers in lower income households.

Given the importance of understanding the extent to which the CfC initiative had succeeded in closing the gap between the most disadvantaged and relatively less disadvantaged children in the CfC areas, the analysis in Phase 1 looked at outcomes for the most disadvantaged families in the CfC sites compared to similarly disadvantaged families in the contrast sites. Disadvantage was operationalised in the study in two ways:

- families where primary carers had a lower level of education (Year 10 or less); and

- families with lower incomes (bottom 20% of the sample income distribution).

The following positive changes between Wave 1 and Wave 3 were found for the CfC intervention, which varied according to the families' levels of disadvantage:

- for primary carers with a lower level of education:

- children's improved receptive vocabulary and verbal ability;

- a decrease in the rates of injuries requiring medical treatment;2

- greater involvement in community service activities;

- for primary carers with higher levels of education, a reduction in the level of hostile/harsh parenting practices;

- for lower income households, an increase in the quality of the home learning environment; and

- for higher income households, a decrease in the level of hostile/harsh parenting practices.

Therefore, there was some evidence that the most disadvantaged families benefitted to a greater extent than less disadvantaged families from the CfC initiative in regard to measures of early learning and community engagement. However, this was not the case for hostile or harsh parenting practices, where a positive effect was only found for relatively high-income households (Edwards et al., 2009). Overall, the Phase 1 evaluation concluded that the results were promising, particularly given the short amount of time that the CfC initiative had been in place across the participating sites. Although most of the effects were small, they were similar, if not greater, to those found for many alternative early childhood interventions. The comparability with the effects of other childhood interventions could potentially be attributable to the distinguishing characteristics of CfC, including its highly coordinated service provision and community-focused approach (Edwards et al., 2009).

1.3 Justification, objectives and key features of Phase 2 of Stronger Families in Australia

In the Phase 1 evaluation report, we argued that it was important to understand which elements of the program are most effective, and "whether the CfC is a strategy that can sustain benefits in the long term, and whether longer exposure to the CfC at a later stage in operation can produce greater benefits is unclear" (Edwards et al., 2009, p. 34). Although the Phase 1 evaluation provided several encouraging findings with regard to the potential benefits of CfC, the number and scope of these effects were possibly limited by the short time over which the initiative had been running (i.e., in most sites, just under one year). Therefore, Phase 2 of the study was necessary to evaluate the medium- to longer-term effects of CfC, and identify whether there were any benefits associated with the program for the study children and their families following school entry (i.e., when children were aged 7-8 years, at the start of Phase 2). This is a particularly important question given that the majority of services target preschool children and parents. A key focus of the Phase 2 CfC evaluation was therefore to investigate whether these gains were sustained as children reached school age. Additional longitudinal data have also been collected that may facilitate better explanations or further substantiate some of the Phase 1 effects. This notwithstanding, the overarching aim for the Phase 2 evaluation remained the same as that in Phase 1: to measure changes in child, family and community outcomes in the CfC communities, and to ascertain the extent to which these effects are related to the CfC initiative.

2. Methodology

2.1 Study design

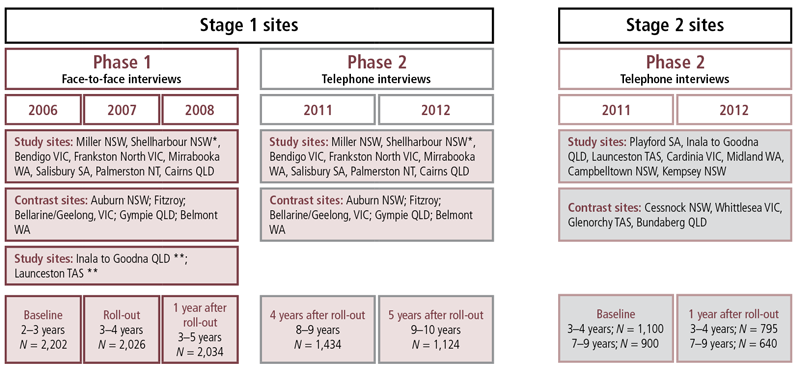

The study design and selected sites for both phases of the SFIA study are shown in Figure 2.1. This diagram shows the CfC study and contrast sites from Phase 1 and Phase 2, the years in which data have been collected and the sample sizes for each wave. Figure 2.1 also shows that there were two CfC study sites that were given additional funding to focus more on risk factors for child abuse and neglect. More information about the Stage 2 sites and the establishment of the Stage 2 cohort is provided in the Appendix ("Stage 2 sites"). It is important to note, however, that the existing study children from these two sites with additional funding (Inala to Goodna and Launceston) were still followed as part of the CfC cohort, and thus are included in the results presented here.

Figure 2.1: Stronger Families in Australia study design

* Building Australia’s Future Workforce (BAFW) site.

Sampling frame: random sample of Family Tax Benefit (Part A) recipients in study locations. Outcomes: healthy families, supporting families & parents, early learning & care, child-friendly communities. All sites are funded under the Communities for Children Facilitating Partner model. There are 52 sites in total, which includes 8 CfC Plus sites (4 are new CfC Plus sites and 4 are enhanced existing CfC sites).

** Inala to Goodna QLD and Launceston TAS were converted to CfC Plus sites for Phase 2.

2.2 Site selection

For Phase 2, Phase 1 respondents from the original ten CfC sites and five contrast sites were followed up in Wave 4 and Wave 5. The ten CfC sites selected were from a total pool of 45 sites where the CfC initiative was implemented. As was reported in Edwards et al. (2009), a structured approach was applied in initially selecting these sites.

In order to avoid respondent burden, areas sampled for the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) were excluded. At least one site from each Australian state and territory was included, and sites had to be sufficiently large to meet the sampling quota.

In addition, five contrast communities were "matched" to the ten CfC sites. The contrast sites were chosen from the same states and territories as the CfC sites and were also similar in location, size and socio-economic status (as measured by the ABS Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas, or SEIFA, score). Sites in the pool of possible communities considered for CfC funding, and communities where the Australian Early Development Index (AEDI) was administered, were also considered. As per the CfC sites, a sufficient population size of 2-3 year old children (the age of the study children in Wave 1) was required.

2.3 Phase 2 sample recruitment

In September-October 2011, DSS provided the fieldwork agency, the Social Research Centre, with the sampling units for the Phase 2 CfC evaluation. The sample file for the continuing CfC cohort provided up-to-date contact records and details for the Phase 1 participants. A total of 2,037 records were provided across all of the CfC and contrast sites, with 2,011 of these having eligible contact numbers.

A pilot study tested the questionnaire before the start of the main study. As part of the pilot study, the Social Research Centre mailed out to all potential respondents a pre-approach letter introducing the study and encouraging participation. A freecall (1800) telephone number to assist with query resolution was sent to sample members, in addition to a brochure providing more information about the SFIA study and the study's website address. A random selection process was applied in selecting the pilot study sample, with 55 interviews conducted in total.

Following the conclusion of the pilot study in late October 2011, the main data collection periods for the CfC cohort were November 2011 to January 2012 (for Wave 4), and September 2012 to November 2012 (for Wave 5). The sample was released in batches so that calls to each could be exhausted before releasing new numbers. Similarly to the pilot study, letters were sent out to the sample members within each batch a few days prior to the commencement of interviews.

A number of call procedures were applied in order to maximise the quantity as well as representativeness of the sample. These included spreading contact attempts over weekdays, weekends, and across various parts of the day; calling later in the day to ensure respondents in WA, SA and NT were called, up until 8:30 pm; using the contact details for both parents; leaving voicemail messages on mobile phones; scheduling appointments so sample members could complete their interview at a convenient time; and calling sample members back until non-contact records were resolved.

The interviews were conducted with the person in the family who knew most about the child (the primary carer). In most cases (96%), this was the mother. In the remaining cases, the primary carer was the child's resident father, a relative who was the primary carer for the child or a foster parent.

2.4 The questionnaire and interviewing methodology

The survey instrument was developed with a focus on including the primary outcome measures that would enable the effects of the CfC initiative to be evaluated. Although it was important to retain as much of the Phase 1 questionnaire content as possible so that longitudinal data across the same measures could be collected for the CfC cohort, some changes were necessary due to:

- using a different data collection method - at-home interviews were conducted in Phase 1 versus telephone interviews in Phase 2; and

- time restrictions - the mean interview length in Phase 1 was approximately 60 minutes, but in Phase 2 were restricted to 25 minutes.

Once all of the items were confirmed for the questionnaire, the Social Research Centre transformed the content into a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) script, and performed a thorough testing process to ensure all skips and loops worked correctly.

2.5 Outcome measures

In Phase 1, the primary outcome measures related to the four overall objectives of the Australian Government's former Stronger Families and Communities Strategy (2004-09), of which CfC was an integral part. These were:

- healthy young families;

- supporting families and parents;

- early learning and care; and

- child-friendly communities.

In Phase 2, we slightly modified the first and second of these categories, primarily to reflect the ageing of the study child. The "healthy young families" category from Phase 1 was divided into child behaviour and primary carer's health. The "supporting families and parents" category from Phase 1 was also divided, into parenting style, parental conflict, and jobless households. Box 1 contains details about the outcome measures included in the analysis.

Box 1: Outcome measures

Child behavior

- The number of child injuries requiring medical attention in the past 12 months.

- Child physical functioning, as assessed using the 8-item Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) Inventory (Varni, Burwinkle, Seid, & Skarr, 2003).

- Child emotional and behavioural problems, as assessed using the 20-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997).1

- A global rating of the primary carer's physical health.

- The primary carer's mental health, as measured using the 6-item Kessler-6 scale (Kessler et al., 2003).

- Argumentative relationship, assessed through a 5-item scale of the frequency of verbal and physical arguments, derived from LSAC.

- A measure indicating a jobless household (no parent in paid employment).

Parenting style

- Primary carers' self-ratings of hostile/irritable parenting and warmth, sourced from LSAC and the National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth (NLSCY; Statistics Canada & Human Resources Development Canada, 1995).

- A single-item measure of parenting self-efficacy, taken from LSAC.

Early learning and care

- Primary carer or other adult read with study child from a book every day or almost every day.

- Primary carer or other adult drew pictures or did other craft activities with the study child every day or almost every day.

- Primary carer or other adult played music, sang songs, danced or did other musical activities with study child every day or almost every day.

- Primary carer or other adult played a game outdoors or exercised together (like walking, swimming, cycling) with the study child every day or almost every day.

Child-friendly communities

- A single item detecting primary carer's involvement in community service activities, such as volunteering at school or coaching a sports team.

- Community social cohesion, measured on a 5-item scale relating to primary carer's perceptions of trust, reciprocity and shared values existing between individuals in the local community (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997).

- Neighbourhood unsafe to raise children, based on three items indicating whether the neighbourhood is safe and clean in general, and safe for children in particular.

- A measure of unmet service needs, focusing on difficulties accessing medical, developmental, family support or mental health services.2

Notes:

1 This measure is applicable to children 4 years and over only, and so is measured at Wave 4 only.

2 This indicator was developed in Phase 1 of SFIA, which assessed whether respondents had difficulties accessing medical, developmental, family support or mental health services. In Phase 2, an additional component was included for these service areas, which inquired as to whether any of the occasions in which the applicable services were required were an emergency or crisis.

Overall, these scales (i.e., multi-item measures) have demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (see Edwards et al., 2009). As previously mentioned, it was not possible to retain all outcome measures due to a reduced interview length and change in interview method (i.e., from face-to-face to telephone), but as many as possible were retained so that changes in these outcomes could be tracked over time for the CfC cohort.

There are a few changes to the outcomes measured in Phase 2 of the evaluation. There were 19 outcome variables in Phase 1, with 15 of these outcomes measured at Wave 1 and Wave 3. We measured all except two of these outcomes again at Wave 4 and Wave 5. The measure relating to community facilities and a measure of children's weight were not collected at Waves 4 and 5, and in both cases, the move from face-to-face to telephone interviewing was the key factor. The measure of community facilities was dropped because of interview time constraints, and the telephone interview format was deemed unsuitable for collecting data on children's weight.

Another change relates to the measure of early learning and care, measured in Phase 1 using a single indicator. In Phase 2, we divided this into four distinct activities (bearing in mind that the study children were older and that it was important to distinguish between different aspects of the home learning environment).

It is important to note that for some outcomes, higher scores are positive (e.g., child physical health), while for other outcomes, higher scores are negative (e.g., hostile parenting). Therefore, it follows that a positive effect (+) indicates an improvement for positively scaled outcomes (e.g., increased child health), while a negative effect (-) indicates an improvement in negatively scaled outcomes (e.g., decreased hostile parenting). In order to facilitate the interpretation of the results (see Chapter 3), Table 2.1 summarises all the outcomes used in the evaluation and reports the direction that indicates a positive outcome of CfC.

| Outcome measure | Direction of positive effects for CfC |

|---|---|

| Child number of injuries requiring medical attention | - |

| Child physical health (PedsQL) | + |

| Child total emotional and behavioural problems (SDQ) | - |

| Primary carer's general health (high health) | + |

| Primary carer's mental health problems | - |

| Hostile parenting | - |

| Parenting high self-efficacy | + |

| Parental conflict | - |

| Living in a jobless household | - |

| Primary carer reading with child | + |

| Primary carer doing arts and crafts with child | + |

| Primary carer playing music with child | + |

| Primary carer playing outdoor games and exercising with child | + |

| Primary carer's involvement in community service activity | + |

| Community social cohesion | + |

| Community unsafe for children | - |

| Unmet service needs | - |

2.6 Response rates and attrition

2.6.1 Response patterns

Table 2.2 shows the response patterns for the CfC cohort in Phase 1 (Waves 1 to 3) and Phase 2 (Waves 4 and 5). A total of 1,434 telephone interviews were completed at Wave 4, which represents a 74% response rate for the total sample of 1,923 participants, drawn from 2,011 contact numbers that were provided in the sample file. Some call outcomes - including disconnected numbers and the named person not being known - were excluded from this figure, thereby reducing the total sample to 1,923. Some families who participated in Wave 1 did not participate at Wave 4 because either they could not be contacted via telephone (n = 256; 13%), or they explicitly refused or opted out (n = 181; 9%). At Wave 5, 1,124 interviews were completed, representing an 85% response rate out of 1,328 eligible contact numbers. Only a small proportion actually refused to be interviewed at Wave 5 (n = 85; 6%). The remaining non-responses were associated with non-contact (n = 52; 4%), or the respondent was away for the entire data collection period, or otherwise out of scope (n = 55; 4%). Finally, appointments were made for 12 respondents but no interview was completed.

| Wave and year | Total sample | Total interviews | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | |||

| Wave 1, 2006 | 3,379 | 2,202 | 65.6 |

| Wave 2, 2007 | 2,202 | 2,014 | 92.0 |

| Wave 3, 2008 | 2,034 | 1,835 | 90.3 |

| Phase 2 | |||

| Wave 4, 2011 | 1,923 | 1,434 | 74.6 |

| Wave 5, 2012 | 1,328 | 1,124 | 84.6 |

As can be observed in Table 2.2, the Wave 4 response rate was lower than those for Waves 2 and 3. Although there was less than 12 months between Waves 2 and 3, there was a much larger gap of 3.5 years between Waves 3 and 4, thereby making retention more difficult. The response rate at Wave 5 increased, though it is clear that attrition continued as the study progressed.

2.6.2 Attrition in CfC cohort

As noted in Table 2.2, there was a modest degree of sample attrition in the CfC cohort in Phase 2. To analyse the reasons for this attrition, we took the sample at Wave 1 and identified those who responded to Waves 4 and 5 and those who dropped out. We then conducted a logistic regression analysis to examine factors (measured at Wave 1) associated with dropping out of the survey at the later waves. The variables included in the regression analyses were: whether the child was of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin; the age, education and employment status of the primary carer; whether the primary carer was born overseas; household income; and whether the father was "present and working", "present and not working" or "absent".

The results, reported in Table 2.3, show that there was no significant difference in the attrition rates between families in CfC sites and those in comparison sites. However, attrition was significantly associated with a range of factors. Families where the primary carer had completed Year 12 or were older were less likely to drop out. Lone-parent families and families where the second parent was not employed were significantly more likely to drop out, as were families with primary carers in paid employment. Families where the primary carer was born overseas were significantly more likely to dropout. Differences in attrition rates were not, however, associated with household income. It is typical for attrition to be associated with the factors reported in Table 2.3 (see Daraganova & Sipthorp, 2011, for details of factors associated with attrition in LSAC). It is important, therefore, to control for these factors to guard against bias in the results arising from attrition.

| Wave 4 | Wave 5 | |

|---|---|---|

| CfC site | 1.08 | 1.11 |

| Child is Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander | 1.63 ** | 1.64 ** |

| Primary carer older | 0.59 *** | 0.50 *** |

| Primary carer completed Year 12 | 0.78 * | 0.83 |

| Primary carer employed | 1.73 *** | 1.55 ** |

| Father present not working | 2.13 *** | 2.40 *** |

| Father not present | 1.69 *** | 1.95 *** |

| Primary carer born overseas | 1.32 * | 1.75 *** |

| Household income | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No. of observations | 2,202 | 2,202 |

Notes: N = 1, 927; *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05. Odds ratios < 1.0 reflect a negative association. Odd ratios > 1.0 reflect a positive association. Odds ratios ? 1.0 reflect no association.

In addition, we estimated models including interactions between each of these variables and a variable indicating the families that live in a CfC site (results not shown). This allowed us to test whether the association between sample attrition and any of these factors differed for families in CfC and contrast sites. It would allow us to see, for example, whether the primary carer's level of education influenced dropout in CfC sites but not contrast sites. If this were the case, we would have evidence for selective attrition, which could affect the validity of the contrast sites. The main effect for all CfC interactions was insignificant, which indicates clearly that patterns of attrition were similar for CfC and contrast sites. In other words, there was no selective attrition with respect to the family characteristics observed in the study.

2.7 Evaluation design and analytic approach

In this report, we employ a range of analytic techniques to explore patterns of change and stability across the range of indicators in both comparison and CfC sites, from the onset of the study (Wave 1) to the most recent data collection (Wave 5). Following the approach in the Phase 1 evaluation we omit data collected at Wave 2 due to the relatively short period of time between Waves 1 and 2 (less than 1 year). We first provide a descriptive overview of outcomes at baseline (Wave 1) and then provide a further description of patterns of change across Waves 3, 4 and 5. We do this for the whole sample, and for subgroups based on income and education (details of which are provided below).

We then test whether there are significant differences at each point in time from baseline through to Wave 5 using cross-sectional regression analyses that control for the gender and age of the child; whether the child was of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin; primary carers' age, education and labour force status; household income; whether at least one of the parents was born overseas; and whether the father was "present and working", "present and not working" or "absent". This analysis allows us to assess whether differences between CfC and comparison sites emerged (or disappeared) at particular points in time.

Following descriptive and multivariate analyses at each wave, we employed difference-in-difference modelling to assess differences in patterns of change between waves in CfC and comparison sites. This approach compares a treatment (CfC) group with a contrast group at multiple points in time. The basic premise of this approach is that the patterns observed over time in comparison sites are those that would have prevailed in CfC sites had there been no intervention. Underscoring this premise is the requirement that the CfC and comparison sites were broadly comparable initially. However, with the difference-in-difference approach, it is possible to explicitly control for any known differences in the CfC and contrast sites so that these do not influence the robustness of the findings.3 Therefore, this approach provides a relatively strong indication of a program effect, but because it relies on changes, it depends heavily on precise estimates of those changes, and thus can be vulnerable to issues around measurement error. In other words, the capacity to detect statistically significant differences in changes in outcomes is dependent on the precision of the measurements at two time points.

The difference-in-difference model specifications include a variable indicating whether the family lived in a CfC site or a comparison site (comparison is the reference site). In addition, they include a variable indicating whether the observation is at Wave 1, Wave 3, Wave 4 or Wave 5 (Wave 1 is the reference time point). The key variables in these models are interactions between the indicators for CfC and Waves 3, 4 and 5. These variables tell us whether there was a significant difference in the change in an outcome at Waves 3, 4 or 5 relative to Wave 1 for CfC families relative to contrast families. In other words, it will tell us whether CfC families changed between Wave 1 and Waves 3, 4 or 5 at a greater or lesser rate than contrast families, or whether there are no significant differences between the rates of change for the two groups.

The additional control variables included in all difference-in-difference regression analyses were: the gender and age of the child; whether the child was of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin; primary carers' age, education and labour force status; household income; whether at least one of the parents was born overseas; and whether the father was "present and working", "present and not working" or "absent".4

Although the difference-in-difference models provide the strictest test of program effects, the methodological approach in this report is motivated by an understanding of the complexity of the program and of the nature of change in this context. Therefore, we have sought to provide a comprehensive overview both of patterns in the outcomes between comparison and CfC sites at distinct points in time, and of patterns of change in stability in these outcomes over time in comparison and CfC sites.

3. The effects of the CfC initiative on child, family and community outcomes

This chapter describes differences between families in CfC and comparison sites across the five waves of surveys for Stage 1 CfC sites. We report the average levels for all outcomes (unadjusted for other factors) at each wave, though we only report on findings that remained statistically significant after adjusting for other factors at each wave. These are equivalent to the cross-sectional results from Phase 1 of the evaluation. In addition, we provide details of significant results from difference-in-difference models, which provide an indication as to whether there have been significant differences in rates of change at Waves 3, 4 and 5 compared with Wave 1 between comparison and CfC sites (more details of this methodology are given in section 2.7).

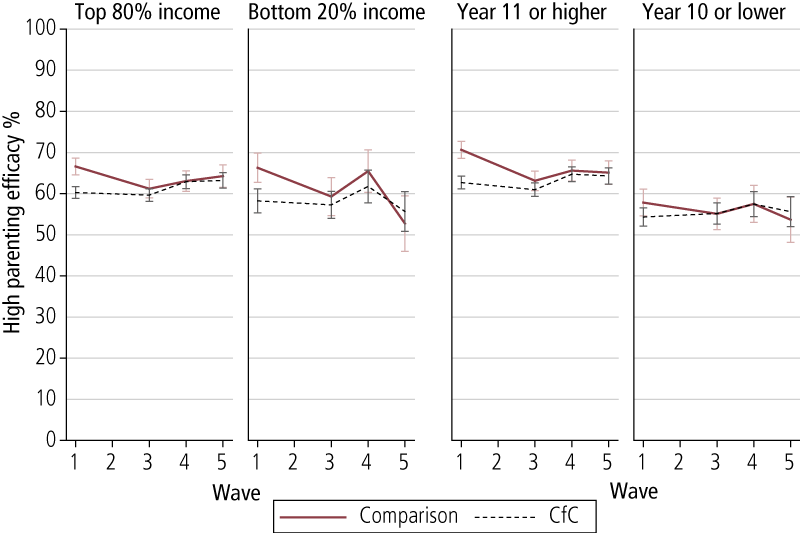

Following the methodology established in Phase 1, in addition to analysing the overall sample, we analyse subgroups relating to income and education. Firstly, we consider lower income families (bottom 20% of income distribution at Wave 1) compared with higher income families (top 80% of income distribution at Wave 1). Secondly, we look at families with a lower level of education (primary carer has Year 10 or lower) compared with the remaining families (primary carer with Year 11 equivalent or higher). These analyses provide an opportunity to explore the robustness of findings for the overall sample and to assess whether the effects are more or less pronounced within different groups. Note, however, that the reduced sample size for the subgroup analyses (especially for subgroups with lower income or education) likely reduces the power of the analyses to detect statistically significant differences.

Table 3.1 reports the proportion of families with a primary carer who had higher and lower levels of education with families with incomes in the top 80% and in the bottom 20%. Overall, about one-third of families had a primary carer with a lower level of education (Year 10 or lower) at Wave 1. Not surprisingly, the majority of families with a primary carer who had a higher level of education had an income in the top 80% of the distribution of income at Wave 1. Perhaps more surprisingly, among families in the bottom 20% of the income distribution, about half of the primary carers had Year 11 or higher and half had Year 10 or lower. This suggests that the level of education of the primary carer is perhaps less effective as a means of identifying the most disadvantaged families with children of these ages. It does serve, however, as a useful comparison group to further assess the effects of the CfC initiative.

| Education level | Top 80% income (%) | Bottom 20% income (%) | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 11 or higher | 71.1 | 51.1 | 66.9 |

| Year 10 or lower | 28.9 | 48.9 | 33.1 |

| Totals | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Notes: c2(1), 65.6; p < .001 indicates a significant degree of association (i.e., non-independence) between these indicators.

3.1 Jobless families

This section considers results relating to jobless families. We start with a descriptive overview of rates of jobless families in CfC and comparison sites in Waves 1, 3, 4 and 5, and further explore patterns in income and education subgroups. Finally, we present results from difference-in-difference analyses.

3.1.1 Descriptive overview

Table 3.2 reports the proportions of jobless families in CfC and comparison sites across four waves of the study, including Phase 1 (Waves 1 and 3) and Phase 2 (Waves 4 and 5) of the evaluation. Rates of joblessness were very similar between the two types of sites at Wave 1, though they are slightly lower in CfC sites (a marginally significant difference; p < .08). By Wave 3, a significant difference in joblessness emerged, and this was one of the key findings from Stage 1 of the evaluation.5 However, by Waves 4 and 5, rates of joblessness were again very similar in the comparison and CfC sites.

| Wave 1 (%) | Wave 3 (%) | Wave 4 (%) | Wave 5 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison sites | 29.1 + | 24.4 ** | 18.8 | 16.1 |

| CfC sites | 27.1 | 19.4 | 17.0 | 14.9 |

Notes: Significant differences are derived from cross-sectional regressions adjusted for child gender and Indigenous status, primary carer age and education, and cultural background. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; + p < .08.

3.1.2 Patterns in income and education subgroups

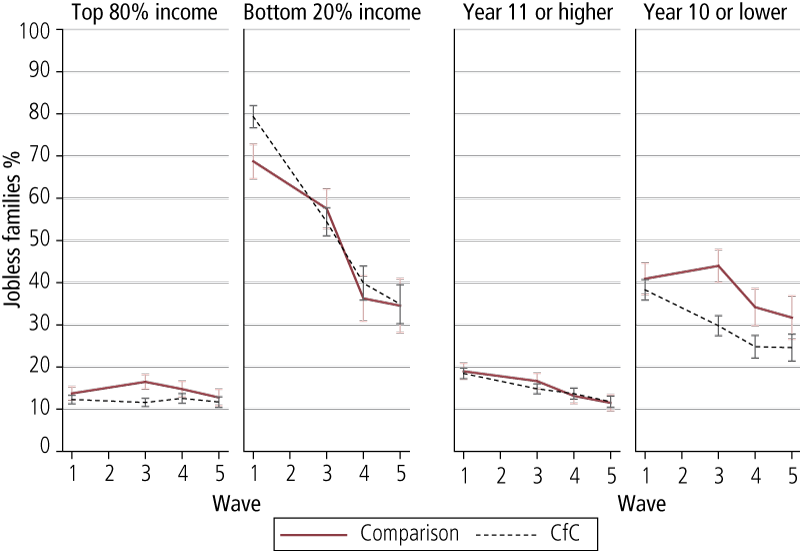

Figure 3.1 reports the proportion of jobless families in CfC and comparison sites, further disaggregated by the lower and higher income and education subgroups. Not surprisingly, rates of joblessness were substantially lower in the relatively more advantaged families in both CfC and comparison sites, and across waves. This was particularly pronounced with the income subgroup.

Figure 3.1: Proportion of jobless families at Waves 1, 3, 4 & 5, by level of income and education, comparison and CfC sites

Looking at the majority of families in the top 80% of the income distribution (at Wave 1) the pattern of joblessness across waves very much drives the patterns reported in Figure 3.1, with a significant difference only emerging at Wave 3. However, the difference was not sustained, with rates of joblessness at Waves 4 and 5 being very similar between CfC and comparison sites.

There was a dramatic decrease in joblessness from Wave 1 to Wave 5 for families who were in the bottom 20% of the income distribution at Wave 1 in both CfC and comparison sites. The rate of joblessness appeared to be somewhat higher for families in CfC sites at Wave 1, but this was not statistically significant after adjusting for other factors. At all other waves, for this lower income group, rates of joblessness in CfC and comparison sites were very similar.

The third and fourth panels of Figure 3.1 relate to families where the primary carer had higher and lower levels of education respectively. In the families with a primary carer with Year 11 or higher education, the rates of joblessness dropped over time in a very similar fashion for both CfC and comparison sites, and there were no statistically significant differences between these subgroups at any wave. The presence of a relatively high proportion of lower income families in the subgroup with higher levels of education likely underscores the relative similarity of joblessness at Wave 3 between comparison and CfC sites in the subgroup with higher levels of education. (It is important to bear in mind that half of families in the lower income group, where there was no significant difference in joblessness at Wave 3 between CfC and comparison sites, had Year 11 or equivalent; see Table 3.2.)

Rates of joblessness were higher among families where the primary carer had a lower level of education (Year 10 or lower). This is particularly the case with comparison group families, who had significantly higher rates of joblessness than CfC families at all waves except Wave 5. The difference in rates of joblessness across all waves between subgroups with higher and lower levels of education is less pronounced than the differences observed between higher and lower income subgroups, which is likely because these education subgroups are more diffuse with respect to income, which was particularly strongly associated with joblessness. This is likely to be because some primary carers with higher levels of education temporarily give up employment when they have children, and thus are temporarily in the lower income bracket. Once their children are old enough to attend child-care, many of these primary carers return to work. Primary carers who have Year 10 or below may not have similar opportunities to return to the workforce, as their workforce participation is likely to have been much lower before they had children in the first place.

3.1.3 Difference-in-difference results

As described in section 2.7, we estimated difference-in-difference models to assess the program's effects. We used these models to compute estimates of the percentage change in the odds of being a jobless family at different points in time for families in comparison and CfC sites. In addition, we tested the extent to which there were differential effects in CfC sites compared with comparison sites. This is captured in the model using an interaction between waves and the variable indicating whether the family lived in a CfC site. In assessing the patterns of change over time, we consider changes in odds in tandem with a more descriptive assessment of changes in the outcomes over time.

Table 3.3 shows the percentage change in the odds of being a jobless family at Waves 3, 4 and 5 compared with Wave 1, for families in comparison sites and CfC sites.

| Comparison sites (% change in odds) | CfC sites (% change in odds) | |

|---|---|---|

| Wave 3 compared with Wave 1 | -10.5 | -48.7 * |

| Wave 4 compared with Wave 1 | -39.7 | -40.4 |

| Wave 5 compared with Wave 1 | -47.1 | -41.4 |

Notes: Statistical significance is derived from difference-in-difference models. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; + p < .08.

The odds of being a jobless family at Wave 3 compared with Wave 1 for families in CfC sites was 49%, whereas for families in comparison sites, the odds reduced by only 11%. The difference in these reductions is statistically significant (p < .05). In other words, the percentage reduction in the odds of being a jobless family was significantly greater in CfC sites than in comparison sites. This echoes the results reported in Table 3.2, which shows a 5% decrease in joblessness in comparison sites (between Wave 1 and 3) compared with an 8% decrease in CfC sites over this period. This is simply a restatement of one of the key findings from Stage 1 of the evaluation, highlighting a positive effect relating to joblessness.

Table 3.3 also shows that for both CfC and comparison sites, there was a substantial reduction in the odds of being a jobless family at Waves 4 and 5, compared with Wave 1. The similarity between CfC and contrast sites in the reduction by Waves 4 and 5 echoes the descriptive results reported in Table 3.2.

Table 3.4 shows the percentage change in the odds of being in a jobless family at Waves 3, 4 and 5 compared with Wave 1 for families in CfC and comparison sites for the income and education subgroups. We present the results for the relatively more disadvantaged families, as this was the only group with significant differences. The results highlight a significant difference in the percentage reduction of the odds of being in a jobless family between comparison and CfC sites in relatively more disadvantaged groups. Specifically, for lower income families, the reduction in the odds of joblessness at Wave 3 was significantly greater in CfC sites (86%) compared with comparison sites (62%), but by Waves 4 and 5, although families still had significantly reduced odds of being jobless, there was no longer a statistically significant difference between CfC (94%) and contrast sites (90%). There was a similar result among lower educated families, where differences in the change in odds at Wave 3 were no longer evident at Waves 4 and 5. Surprisingly, for lower educated families, the odds of being jobless at Wave 3 compared with Wave 1 increased by 30% in comparison sites, while the odds reduced by 61% in CfC sites. However, as with the overall results, at Waves 4 and 5 there were no longer any significant differences in any changes in the odds of being a jobless family between comparison and CfC sites, compared with Wave 1.

| Comparison sites (% change in odds) | CfC sites (% change in odds) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bottom 20% of income | ||

| Wave 3 compared with Wave 1 | -62.4 | -85.6 * |

| Wave 4 compared with Wave 1 | -87.6 | -92.5 |

| Wave 5 compared with Wave 1 | -89.5 | -93.9 |

| Year 10 or lower | ||

| Wave 3 compared with Wave 1 | 29.7 | -61.3 * |

| Wave 4 compared with Wave 1 | -14.2 | -55.4 |

| Wave 5 compared with Wave 1 | -15.3 | -44.9 |

Notes: Statistical significance is derived from difference-in-difference models; *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; + p < .08.

These results suggest that the CfC initiative reduced the rate of jobless families when the target children were aged 4-5 years, but that by the time children were 7-8 years of age, increased employment in families in comparison sites meant that rates of joblessness converged. The improvement corresponds to a period when the target child was entering school, which would have provided all primary carers with more free time to engage in the workplace and may explain the similar reduction in jobless households for contrast sites at this later wave. Importantly, while the trajectories of the two groups were different over the four waves (with CfC families benefitting from lower levels of joblessness earlier on than contrast families), there was no significant difference between them by Waves 4 and 5.

What is unknown is whether there are any demonstrable benefits to children or their families from the earlier reduction of joblessness in CfC sites. The findings indicate that children in CfC families were likely to have spent less time in total growing up in a jobless family. Certainly there is good evidence to suggest that at the individual level, the longer the duration of unemployment the greater the negative effects (e.g., on mental health, Paul & Moser, 2009; subsequent employment and earnings, Arulampalam, Gregg, & Gregory, 2001; and child wellbeing, Gray & Baxter, 2012). We will explore this issue when we examine associations between joblessness and children's educational outcomes, using NAPLAN data, in Chapter 6.

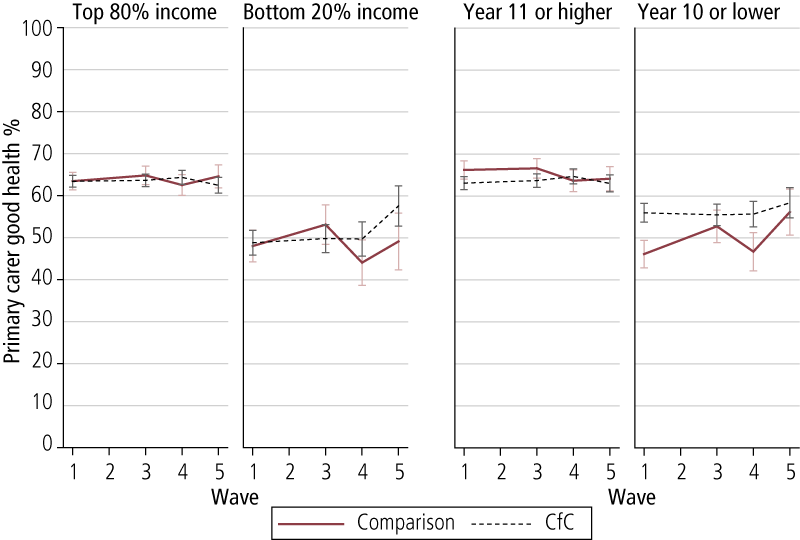

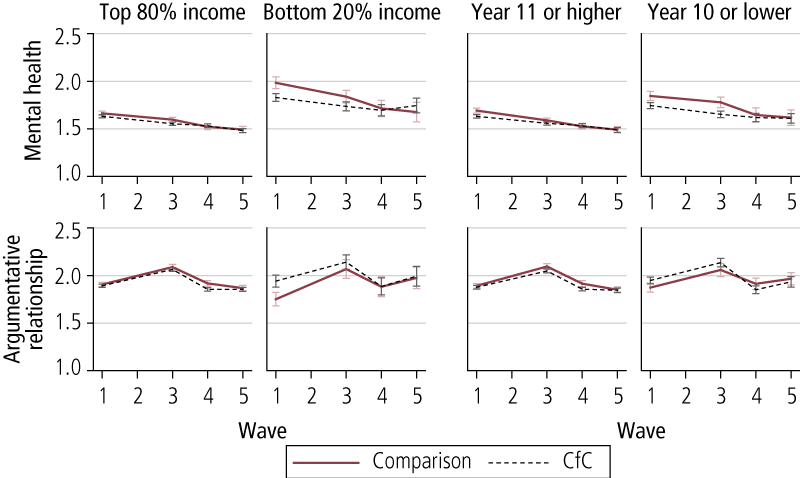

3.2 Primary carer health