Gambling in Suburban Australia

March 2019

Angela Rintoul, Julie Deblaquiere

Download Research report

Overview

This study explores how the characteristics of local neighbourhoods and gambling activity interrelate. Its particular focus is on electronic gambling machines (EGMs, or 'pokies') and the venues that host them.

The report presents a novel mixed-methods study of a social phenomenon that has not yet been well explored: the relationships between place, social circumstances, gambling and harm. It compares two socially distinct areas of a major city (Melbourne, Victoria) to identify a range of issues that warrant further exploration for policy purposes. It considers:

- how socio-environmental factors may influence local gambling consumption

- how the characteristics of local communities may interact with local gambling opportunities to influence gambling consumption

- the localised effects of gambling on people who gamble and their 'significant others'.

The study found that high-intensity EGM gambling was easily accessible, especially in the site of higher disadvantage. It found that while gambling consumption is affected by a range of factors, the availability and nature of high-intensity EGM gambling influenced gambling uptake and participation by those who participated in this research, and contributed to a range of health, financial, relationship and emotional harms. These findings have led the authors to propose a range of harm-prevention and reduction measures that may improve public health and protect consumers from gambling-related harms (see section 10.4).

Key messages

-

Like other research, our study found that high EGM availability or saturation coincided with social stress and disadvantage. This poses a risk of higher and more severe levels of gambling‑related harm.

-

Community members and families are attracted to gambling venues by a range of heavily promoted, loss-leading, non-gambling activities and facilities including free or subsidised meals and drinks. The use of these promotions may lead to outcomes that are contrary to venues' Responsible Gambling Codes of Conducts.

-

Even in the less disadvantaged site, with relatively fewer opportunities to gamble, the nature of high-intensity gambling products in local venues may lead people who gamble there, and their significant others, to experience harm from gambling.

-

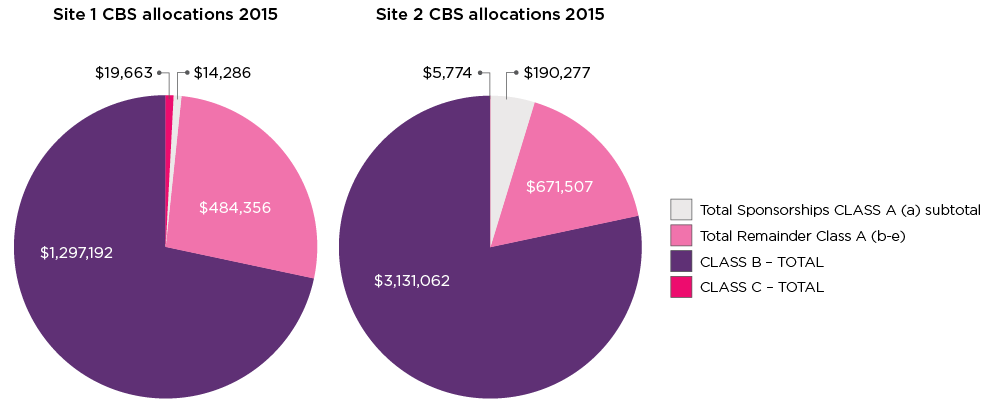

Local residents in both sites reported modest benefits and significant harms from the presence of gambling venues in their neighbourhoods. Analysis of clubs' community benefit statements found that benefits claimed by operators can be overstated.

-

Policies aimed at reducing harm from EGMs should consider the distribution and availability of EGMs in local communities, and the introduction of harm-reduction measures such as universal pre-commitment systems and the restriction of indirect venue promotions.

Executive summary

Australia is unique in the world for the widespread availability of electronic gambling machines (EGMs, or 'pokies') in local community hotels and clubs. In most other countries, high-intensity forms of gambling are largely confined to casinos, meaning people who gamble must make a deliberate effort to visit these venues.

While gambling consumption is affected by a range of factors, including those at the individual level (such as life experiences and stressors), place and social context also play a substantial role in determining the use of available gambling opportunities.

This report will explore the role of social and environmental factors in influencing EGM use in local hotels and clubs. It will show how availability (and, in some cases, saturation) of gambling venues influences EGM use, and how, in disadvantaged areas, the problem is compounded by a lack of alternative social spaces. It will also show how gambling-related harm can be significantly magnified and intensified in areas already experiencing socio-economic stress, when compared with less disadvantaged areas.

Method

The report presents findings of an exploratory place-based study of two geographical areas, each comprising a six-suburb cluster. The study investigates a social phenomenon that has not yet been well explored; that is, the relationship between place, social circumstances, gambling and harm. Site 1 is an area of higher socio-economic disadvantage and EGM density in Melbourne's west; and Site 2 is an area of average socio-economic status and EGM density in Melbourne's east. The method involved: analysis of secondary regulatory and census data to compile a socio-demographic and EGM profile of each site; neighbourhood and EGM venue (n = 11) observations; and interviews and/or focus groups with people who gamble (n = 44), their significant others (n = 20), the general resident population (n = 65) and professionals (n = 30), comprising a total of 159 participants across both sites. The final stage of analysis involved the triangulation of methods to test the validity of findings between the study methods.

Findings

The study found a higher level of geographic and social gambling availability in Site 1 compared to Site 2, as measured through the density of machines and as reported by participants. It also found that the harms from gambling were more pronounced and prevalent in Site 1.

Participants across both study areas reported substantial financial, health, relationship and emotional harms from frequent gambling. However, in Site 1, these harms were magnified by existing disadvantage.

Participants in Site 1 reported that the problem of a high level of gambling venue availability was compounded by a lack of alternative social spaces. Many participants reported that they inadvertently ended up at gambling venues when they were undertaking routine daily activities, such as attending their children's sporting events. This contrasted with evidence from Site 2, where the reported relative abundance of alternative social spaces and activities were combined with fewer EGM venues (see section 3.3).

It is apparent both through researcher observations and reports from people who gambled and venue professionals (in both sites) that EGM operators seek to increase the crossover between the use of non-gambling facilities in venues, such as sporting facilities, the bistro and bar, and the EGM area (see section 4.1). Participants frequently reported using EGMs in venues that they had initially attended for other purposes such as dining or socialising. Participants noted that offers such as free coffee and tea provided in the EGM area may also encourage the use of EGMs.

These offers of free or heavily discounted food, beverages and activities were also seen as impacting other non-gambling businesses who may subsequently experience lower demand for their goods and services (see section 3.4 and section 6.2). Most participants were also sceptical about purported benefits provided by EGM operators to the local community, and the data presented (see chapter 9) support previous recommendations that subsidising local clubs that derive considerable income through operation of EGMs may not be the most efficient way to fund community activities.

Previous research has shown a relationship between people who gamble problematically and social isolation. Trevorrow and Moore (1998) found an association between loneliness, social isolation and women's use of electronic gambling machines. Data from our study (see section 5.4) indicate that social isolation is a risk factor for use of EGMs, and also a result of gambling harm. Some participants who already experienced isolation and loneliness reported they began gambling as a way to address that situation. Others reported that, as a consequence of their harmful gambling behaviour, they were dislocated from their families and social networks.

These experiences were magnified and intensified in areas already experiencing considerable social stress and disadvantage. Participants cited the apparently 'non-threatening' environment of the EGM venue, in which lone attendance is common and where staff seem friendly and welcoming (see section 5.4).

It is possible, since participants self-selected to take part in this study, that they may be more likely to have experienced gambling harms than others in the community. However, we found that, even if our participants' gambling harms were more pronounced than usual, both the immediate and legacy effects of gambling harms represented substantial opportunity costs, and imposed real and often enduring costs in both our study sites on people who gamble, their families, communities and society (see chapters 5, 6, 7 and 8). This finding may illuminate research conducted by Markham, Young, and Doran (2015) that demonstrated that there is no 'safe' level of EGM use.

The harms described by some participants included family breakdown, family violence and other crimes, mental illness and suicide. All participants who gambled reported financial harms, with some describing going without meals, struggling to make mortgage or rental payments, house repossession and homelessness (section 6.2 and section 6.3). In Site 1, where many participants were already under considerable financial and social stress, it was reported that the severity of harms could escalate to crisis levels very quickly. By comparison, many participants in Site 2 were in a position to draw on their own assets or the wealth of extended family to mitigate the damaging effects gambling had on their finances, relationships, health and careers.

Recommendations

The findings of this report highlight the need for further consideration of EGM licensing and regulation, such as the location and number of community-based EGMs and the manner in which they are provided. This was a perspective expressed by many participants in this study (see section 9.1). New policy settings are also recommended.

In section 10.4, 'Recommendations', we propose a range of options to address some of the harms of EGM use. These include:

- Restrict the distribution and level of EGM availability in local communities.

- Provide less harmful gambling machines by introducing a range of well-documented harm-reduction measures.

- Separate alcohol from ambient gambling.

- Create alternative non-gambling spaces where local residents can meet and socialise.

- Restrict indirect venue promotions, including 'family-friendly' subsidies and activities for families and children.

- Increase resources to police and regulators to ensure EGM venues comply with existing laws and regulations.

- Review tax concessions to 'not-for-profit' clubs that operate EGMs, and reform 'community benefit' schemes.

- Require venues and the financial and banking sector to implement improved customer protections.

- Require venues across Australia to provide detailed data about EGM use at venues.

- Invest in research that can inform policies to support the prevention and reduction of gambling-related harm.

- Develop and implement a National Gambling Strategy to provide coordinated direction and support to the prevention and reduction of gambling harm across Australia.

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose of this report

Gambling is recognised as a significant public health and policy issue in Australia. Australians lose approximately $22 billion on legal forms of gambling each year, representing the largest per capita gambling losses in the world (Queensland Government Statistician's Office, Queensland Treasury, 2016; The Economist online, 2014). The largest proportion of gambling expenditure is on land-based EGMs, which account for 62% of all gambling losses (Queensland Government Statistician's Office, Queensland Treasury, 2016). While state governments regulate gambling across their jurisdiction, EGM availability, activity and harm can vary widely at the local level. For instance, studies have demonstrated a social gradient in gambling losses, with areas of higher socio-economic disadvantage losing more than areas of lower disadvantage (Rintoul, Livingstone, Mellor, & Jolley, 2013). This suggests that gambling may be entrenching inequality in already disadvantaged areas.

To date there has been relatively limited research into gambling at the local level. While there have been desktop analyses of locally available administrative data and modelling of predicted and observed EGM catchments (Doran & Young, 2010; Marshall & Baker, 2001; Marshall & Baker, 2002; Rintoul et al., 2013), there have been relatively few qualitative studies that capture the experiences of local residents, and their own explanations of and attitudes towards local gambling opportunities. Reith and Dobbie (2011, 2013) explored the role of the environment and social networks in the development of gambling in Scotland. They argue that qualitative accounts of the social, environmental and political context in which gambling takes place have been lacking. Reith (2012) also argues that the policy and regulatory context in which gambling takes place can have a determinant effect on the prevalence and nature of gambling problems.

Australia provides a unique environment for the study of community-based, high-intensity gambling opportunities. In all but one Australian jurisdiction (Western Australia), EGMs are widely available in local community hotel and club venues. Around 30% of the Australian population use EGMs at least once a year (Queensland Government Statistician's Office, Queensland Treasury, 2016). EGMs are associated with the most gambling-related harm of any form of gambling: around 85% of people who experience gambling harms report EGMs as their main problem (Productivity Commission, 2010).

Using a burden of disease model,1 a recent study revealed that the burden of harm associated with gambling problems is about 60% of that associated with alcohol use and dependence (Browne et al., 2016). In 2010, it was estimated that the social costs of problem gambling in Australia ranged from $4.7 billion to $8.6 billion annually (Productivity Commission, 2010). However, a more recent estimate, which included the costs associated with people who gamble at low- and moderate-risk levels, estimated the social costs to be about $7 billion in Victoria alone (Browne et al., 2017).

This current report contributes to building a framework of understanding of the key determinants of EGM gambling, many of which are yet to be properly investigated. By understanding the key determinants of gambling consumption and harm, solutions to address these harms can be developed in a more coordinated way. It is hoped this study's findings will assist in developing a systematic response to gambling harm in line with, for instance, the responses developed for road transport injury prevention and tobacco control.

1.2 Place and health

This study hypothesises that EGM gambling consumption is influenced by the built environment in which one lives.

There is a growing body of public health research that reveals how the built environment and social and commercial factors influence health outcomes (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008; Kickbusch, Allen, & Franz, 2016; Malambo, Kengne, De Villiers, Lambert, & Puoane, 2016; Marmot & Wilkinson, 2005; Townshend, 2017). This research describes how unhealthy retail stores and services affect health, and argues that health promotion and illness prevention efforts should take in to account the neighbourhood attributes of communities.

The social determinants of health2 describe, in part, how inequalities in outcomes differ across the population. Often these inequalities appear to be avoidable and are the result of structural (or socio-economic) inequity. Increasingly, a tendency of some research to focus on individual choices and lifestyle factors, in the context of addictive consumption such as of tobacco, alcohol and gambling, has been criticised for failing to account for significant commercial, social and economic influences on population consumption patterns (Kickbusch et al., 2016; Livingstone et al., 2017).

To date, little gambling research has reflected the social determinants of health approach. The gambling accessibility literature has gone some way to explaining local EGM venue expenditure patterns by predicting the catchment areas of venues using EGM density, losses, venue size, socio-economic disadvantage and local population to show ecological associations3 of likely levels of harm. However, to date, the research has not progressed beyond evidence of an association between increased EGM density and rates of family violence incidents and assaults (Markham, Doran, & Young, 2016).

Further, little research has progressed beyond abstract statistical description to explain high expenditure clusters in areas of socio-economic disadvantage. Therefore, the authors of this study sought to qualitatively explore factors underpinning the link between socio-economic disadvantage and gambling consumption. Understanding this phenomenon, and its effects on people who gamble, and their families and communities, will assist in the development of improved public policy designed to prevent and reduce gambling-related harm.

Gambling affects a wide range of domains, including household functioning and relationships, health and wellbeing, productivity and employment and, in more extreme cases, can lead to contact with the criminal justice system, family violence, suicidal ideation and suicide (Black et al., 2015; Blaszczynski & Farrell, 1998; Dowling et al., 2016; Productivity Commission, 2010; Wong, Kwok, Tang, Blaszczynski, & Tse, 2014). Harms attributable to high-risk gambling at a population level are similar to major alcohol-use disorder, and moderate-risk gambling has a higher burden of harm than moderate alcohol-use disorder (Browne et al., 2016). It is estimated that for every person who gambles at high-risk levels, on average at least six others are directly affected. For people who gamble at low- and moderate-risk levels, around one and three others, respectively, are affected. Immediate family members such as partners and children are most likely to be affected (Goodwin, Browne, Rockloff, & Rose, 2017).

There are also likely economic effects on local communities via the diversion of money to gambling businesses. For example, subsidised food and other social activities drawing on profits generated through EGM operation may disadvantage non-gambling enterprises offering the same services.

There is some debate about the reasons for high levels of gambling accessibility, and high per capita losses in disadvantaged areas. Typically, EGM operators argue that they are meeting demand for their product. An alternative explanation, explored in this study, is that exposure; that is, supply of gambling products, is a key factor for uptake.

Further, it is possible, and likely, that people living in disadvantaged areas experience higher levels of stress (Boardman, Finch, Ellison, Williams, & Jackson, 2001) and may find temporary relief from this stress through the use of EGMs. Recent studies in neuroscience have demonstrated that use of an EGM can stimulate the striatal dopamine system (Yücel, Carter, Harrigan, van Holst, & Livingstone, 2018). Such stimulation is likely to lead to a temporary sense of relief and reduced anxiety, but clearly can also lead to and entrench excessive gambling.

1.3 Rationale

This study explores the interaction between EGM supply and demand through the experiences and attitudes of local residents, in particular by concentrating on the experiences of people who gambled, and their significant others, in two selected neighbourhoods. While acknowledging that gambling consumption is a function of individual characteristics, neighbourhood context and macro-level influences, the theoretical basis upon which this study was developed is that populations living in more disadvantaged areas:

- have less social and economic resources, leading to higher levels of stress (Boardman et al., 2001)

- experience higher levels of accessibility and exposure to high-intensity EGM products, and are more likely to be exposed to the promotions of these venues and the products that they offer

- have reduced community amenities.

In combination, these factors were hypothesised to contribute to increasing the attractiveness of EGM venues and their promotions. Our aim was to use qualitative data to explore the validity of this hypothesis.

1.4 Aims and research questions

This study is grounded in an approach drawing on the social determinants of health. It is focused on two spatially defined communities in Melbourne, selected for their differing EGM gambling availability and consumption and socio-economic characteristics. This study seeks to understand the effects of these differences in the distribution of gambling opportunities between these areas. This comparison allows us to interpret findings in relation to the distribution of advantages and burdens at a population level (Gostin & Powers, 2006).

The primary aims of the study are to:

- explore and document local environmental factors that influence gambling consumption patterns in selected local areas or suburb clusters. This involves exploring the features and characteristics of gambling venues, as well as the local community context in which gambling occurs

- document the nature and consequences of gambling-related harm among people who gamble, their families and local communities.

The key research questions are:

- How do different environmental factors contribute to gambling consumption in each local area? How does this differ between the two selected local areas?

- How do the characteristics of the local community interact with gambling opportunities to influence gambling consumption?

- What are the nature, consequences and effects of gambling on people who gamble and 'significant others' in this local area?

The study explores factors that determine the ways in which people live, work and socialise in each site. It explores how the characteristics of this local environment (e.g. venue operations, social, economic, geographic and regulatory factors) influence gambling consumption. The study seeks to understand how exposure to gambling and the social capital (community resources and available opportunities), combined with the relative availability of alternative non-gambling recreational facilities, may influence engagement with local gambling opportunities.

The report provides:

- an overview of the methodology (chapter 2, details provided in appendices A and B)

- results that describe:

- factors influencing EGM gambling activity and consumption, including amenity and recreational facilities, and venue accessibility and promotional strategies (chapter 3 and chapter 4)

- life stressors experienced by local residents, including social, financial and structural stressors (chapter 5)

- gambling-related harms, including financial and crisis harms (chapter 6), physical and mental health harms (chapter 7), and relationship harms, including conflict and violence within personal relationships and intergenerational harms (chapter 8)

- community benefits of gambling (chapter 9)

- recommendations and conclusions for preventing and reducing gambling-related harm, particularly harm related to EGM consumption (chapter 10).

1 Burden of disease measures the impact of living with illness and injury and dying prematurely. The summary measure 'disability-adjusted life years' (or DALY) measures the years of healthy life lost from death and illness (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2018).

2 The social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels. The social determinants of health are mostly responsible for health inequities - the unfair and avoidable differences in health status seen within and between countries (World Health Organization [WHO], 2018; see www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/). The commercial determinants are a subset of this field and describe 'strategies and approaches used by the private sector to promote products and choices that are detrimental to health' (Kickbusch et al., 2016).

3 Ecological associations describe the frequency with which an outcome of interest occurs in the same geographic area. These studies are useful for generating hypothesis but cannot be used to infer causal conclusions (Jekel, Katz, Elmore, & Wild, 2007).

2. Method

2.1 Overview

This exploratory place-based study investigates gambling consumption in two sites in suburban Melbourne, Australia. Each site comprises a geographic area consisting of six suburb clusters specially developed for the purposes of this study.

Site 1 was selected for high levels of EGM gambling availability and consumption. This area incorporates six suburbs in western Melbourne within the City of Brimbank, an area of Victoria's highest EGM losses, as well as one suburb in the City of Maribyrnong. The suburbs selected were: Sunshine, Sunshine North, Sunshine West, Ardeer, Albion and Braybrook.

Site 2 was selected as it has around-average levels of gambling consumption compared to the rest of Victoria, and is a similar proximity to the city to Site 1, as well as a similar size (geographical and population). Site 2 comprises a cluster of six suburbs located in eastern Melbourne within the City of Whitehorse, including Box Hill, Box Hill South, Box Hill North, Blackburn, Blackburn South and Blackburn North.

The Box Hill district comprises part of the only 'dry area' in Victoria, where hotel, bar, club and retail liquor licences have been substantially restricted, and licences must be approved through a poll of local residents conducted by the Victorian Electoral Commission (Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation [VCGLR], 2017). Given that it is a prerequisite for EGM licence holders to have a liquor licence, this provides a unique environment for a study of this nature. This arrangement allows for great collective community agency relating to the licensing of unhealthy commodities in Site 2.

In total there were 11 EGM venues in these areas, with eight venues in Site 1 and three in Site 2 (see Appendix A).

The study adopted a range of qualitative and quantitative methods. The report uses data obtained from the following components of the study:

- Secondary data were used to develop a community profile of each site:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016 Census population and housing and socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA) data

- Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) EGM data

- review of socio-historical information relating to each site.

- We carried out site and venue observations (n = 11 venues) and compared activity in these venues against venue Responsible Gambling Code of Conduct (CoC) documents.

- A total of 159 people participated in interviews or focus groups. These included:

- semi-structured interviews with people who gambled and have experienced gambling harm and significant others (e.g. partners, siblings and children of people who gambled) (n = 64)

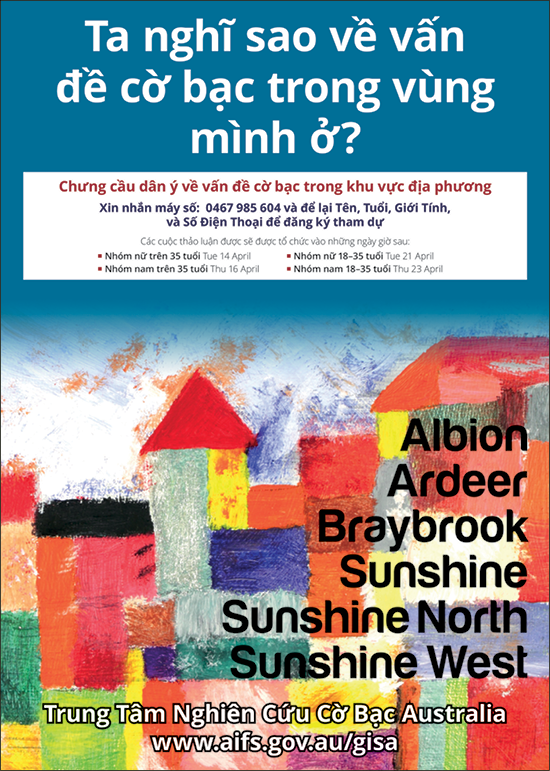

- focus groups with the general resident population: English language in Site 1 (n = 12) and Site 2 (n = 12); people with a disability/carers (n = 3); and Vietnamese language focus groups in Site 1 only (n = 38)

- semi-structured interviews and focus groups in both sites with gambling professionals from venue, treatment and policy and regulation areas, community and social welfare organisations, and local government professionals (n = 30).

The data sources and methods are described in more detail in Appendix A. Appendix B provides study materials.

2.2 Recruitment of study participants

A short survey was developed for the purpose of screening and recruiting potential participants for in-depth interviews with people who gambled and their significant others, and focus groups with other local residents in the general population (described in Appendix A). This survey collected information about usual recreational activities, gambling attitudes and participation, EGM venue visitation, and socio-economic and demographic information (see Appendix B).

Survey administration

The survey was programmed using LimeSurvey™ and a website was developed to support the study. The survey was piloted and minor changes were subsequently made. The online survey completion time averaged 12 minutes. To facilitate the participation of those less comfortable in the online environment, the survey was also adapted to a paper version that could be completed by a researcher face-to-face or over the telephone via a toll-free number.

Survey promotion

All local residents (aged 18+) in each site were eligible to participate in the survey. A variety of approaches were used to promote the study and to recruit participants (see Appendix A for details). Residents were encouraged to complete the survey through the award of $100 supermarket vouchers for randomly selected respondents (n = 50 across two sites).

Advertisements were placed in local newspapers over several weeks in each site as well as online via Twitter, Facebook and Gumtree. A study flyer was distributed to household letterboxes (see Appendix B). Posters and flyers were circulated throughout each study area with support from local councils and services. Local media outlets were contacted with information about the study, with one newspaper in Site 1 publishing a feature story about the study, and a local radio station conducting an interview with a researcher in Site 2 (no equivalent station existed in Site 1). Local Gambling Help Services provided support in the form of dissemination of study promotional materials, referrals of a small number of people who gambled to the study, and the use of interview rooms. The local government and a number of community services within each of the sites also helped by promoting the study and our recruitment information though their networks and providing interview rooms.

Further promotion was conducted directly by attending local community groups and activities including: local cultural groups, the Men's Shed, knitting groups, community lunches, local markets and festivals, neighbourhood houses, non-government organisations and faith-based organisations in each site.

Analysis of survey responses demonstrated that letterboxing of flyers to all households in Site 1 yielded the highest number of survey participants, and social media the least. In Site 2, an opposite pattern was found with social media promotion, primarily Gumtree advertisements, yielding the highest number of participants, while letterboxing achieved lower numbers of participants. Local newspaper advertisements and promotion through local services and community events were moderately successful in both sites.

Timelines

Recruitment in Site 1 was undertaken for 37 weeks from March to September 2015 and from November 2015 to February 2016. In Site 2, recruitment ran for 23 weeks from September 2015 to February 2016. A total of 411 completed survey responses were received; 252 in Site 1 and 159 in Site 2. A small number of participants who lived in suburbs immediately adjacent to the study area (22 in Site 1 and 18 in Site 2) were included in this total. Seventeen responses were excluded as participants reported living in Melbourne but not within the study area or adjacent suburbs.4

From this, sample participants were invited for an interview based on their responses to categories of people who gambled intensely or who reported lifetime harms from gambling and their significant others. Local residents who did not gamble at harmful levels were selected to participate in focus groups. We sought a balance of men and women in each site, as well as a mix of younger and older participants.

Study participants

In addition to those described above (recruited through the survey), local Vietnamese-speaking residents were recruited through the networks of a locally based Vietnamese-speaking research assistant in Site 1. Professionals were recruited by direct approach based on searches of services available in the area and existing researcher networks. A summary of the sample is provided in Table 2.1 below.

| Type of participant | Number of participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Total | |

| Person who gambled and has experienced harm/problems | 24 | 20 | 44 |

| Significant other | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| Focus group (English language) | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Focus group (disability/carer) | 3 | - | 3 |

| Focus group (Vietnamese language) | 38 | - | 38 |

| Professional | 19 | 11 | 30 |

| Total | 108 | 51 | 159 |

Note: Detailed participant data and demographic tables are provided in Appendix A.

Twenty-four people who gambled (16 female, eight male) and 12 significant others (all female) were interviewed in Site 1. In Site 2, a total of 20 people who gambled (16 male and four female) and eight significant others (seven female and one male) were interviewed. A more detailed description of this sample is provided in Appendix A, Table A2.

EGMs were the primary problematic form of gambling for 75% of people who gambled in Site 1 and 70% of people who gambled in Site 2. Of participants who gambled at harmful levels, seven of 24 in Site 1 (29%) and eight out of the 20 in Site 2 (40%) also reported visiting the casino in central Melbourne in the past month. Further detail is provided in Appendix A, Table A3.

2.3 Data analysis and triangulation of results

Descriptive profiles were compiled for both sites. This consisted of the ABS census population in each site, the ABS SEIFA Index of relative socio-economic disadvantage (IRSD) for each suburb, and the VCGLR EGM data for each venue.

All qualitative interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded with consent from participants, and subsequently professionally transcribed. Vietnamese-language focus group recordings were translated and transcribed into English by an accredited National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) interpreter. These transcripts, along with venue CoC documents and summary site observation notes, were uploaded into NVivo 11™ software. Documents were initially thematically coded to nodes by the authors. Codes were refined, sorted and clustered as analysis progressed (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2013; Saldaña, 2015). Coding was cross-checked and validated between both authors who frequently discussed the themes to test observations and insights that were emerging from the data.

The final stage of analysis involved the triangulation of methods to test the validity of findings between the study methods. Triangulation of data from multiple sources enhanced the consistency and applicability of the qualitative components of the study (Noble & Smith, 2015).

The authors presented their findings to staff and/or councillors in each local government area prior to publication.

Participant codes

Quotes from participants reported in the results section are coded to provide anonymous context with reference to the site (1 or 2), study categorisation (person who gambled [G], significant other [SO], local resident [LR], Vietnamese local resident [LRV] or professional [P]) and gender [M] or [F].

2.4 Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was provided by the Australian Institute of Family Studies Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. 14/27) and multicentre approval was obtained from Cohealth and IPC Health (formerly known as ISIS Primary Care).

To address any local concerns about the study, the authors presented their findings to staff and/or councillors in each local government area prior to publication.

4 The primary purpose of the survey was as a recruitment conduit for interviews with people who gamble and significant others and English language focus groups. However, quantitative data on gambling at the local area level in each of the two sites were also collected and are intended to be the subject of a later publication.

3. Community context and local environment

The following chapter examines local community characteristics in relation to the accessibility and use of EGM venues in each of the two sites. This chapter presents analysis of secondary data comparing the two sites, followed by results from local residents and observations by researchers about the nature of amenity of each site. These data describe participant reports about access to alternative recreational facilities and public transport, their experiences or perceptions of crime and safety, and the availability of local gambling venues.

3.1 Census, crime and gambling statistics

Sites for this study were selected on the basis of a range of similarities and differences. Analysis of census and regulator data assisted in determining appropriate sites for this study. The 'vulnerability model' of Melbourne5 (Rintoul et al., 2013) helped to identify boundaries for each site. The two sites are similar in terms of population and land size and are nearly equidistant from the central business district (CBD), in opposite directions. They also have a similar number of households. However, they are markedly different in terms of their history, socio-economic status and ethnic composition. A narrative description of the social and historical context of each site is provided in Appendix C.

As Table 3.1 demonstrates, Site 1 has a high level of socio-economic disadvantage - with population-weighted mean suburb SEIFA IRSD scores (872) well below the state average of 1,010. By comparison, Site 2 has an IRSD score of 1,042, above the state average (ABS, 2016).6

The VCGLR provide venue-level data on their website for each hotel and club EGM venue in Victoria (Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, 2016). This shows Site 1 has higher levels of EGM density and utilisation compared with Site 2, reflected through the number of EGM venues, number of EGMs, losses per EGM and overall losses. Site 1 has many more venues (eight vs three), double the number of EGMs (416 vs 208), and more than three times the amount of EGM losses per adult ($1,252 vs $383).

Victorian crime statistics show that there are much greater incidents of police-reported family violence in Site 1 compared to Site 2 (State of Victoria, 2018). This reflects recent research that has shown a significant association between the number of family violence incidents and assaults and the density of EGMs (Markham et al., 2016).

The key differences between these sites include the proportion of people born overseas, the level of accessibility to gambling opportunities and the higher level of disadvantage in Site 1. All suburbs within Site 1 are ranked in the SEIFA IRSD Deciles 1-2, whereas the range of rankings from Site 2 are 4-9.7 Table 3.1 shows that the rate of police-reported family violence is also higher in this area (8.9/1,000 people in Site 1 vs 3.1/1,000 in Site 2).

The following section reports the views of participants in each site and the research team observations about the community context and local environment. This is intended to provide context about 'pull' and 'push' factors that may lead local residents into gambling venues. It covers alternative recreational facilities available locally, public transport and perceptions and/or experiences of crime.

The responses of participants are largely reported separately by site, given there were very different experiences described.

| Characteristic/variable | Site 1 | Site 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic and demographic data | ||

| Land size | 34.36 km2 | 23.13 km2 |

| No. of households | 21,581 | 26,495 |

| Adult population (18+) | 45,255 | 50,718 |

| SEIFA IRSD population-weighted mean score | 872 | 1,042 |

| Australian born (%) | 39.5 | 56.1 |

| Top 3 countries of birth other than Australia | Vietnam, India, Malta | China, India, Malaysia |

| Top 3 language groups other than English | Vietnamese, Mandarin, Cantonese | Mandarin, Cantonese, Greek |

| Rate of police-reported family violence-related incidents/1,000 adults | 8.9 | 3.1 |

| Gambling data | ||

| No. of EGM venues | 8 | 3 |

| Clubs | 3 | 2 |

| Hotels | 5 | 1 |

| No. of EGMs | 416 | 208 |

| Range venue no. of EGMs | 18-78 | 39-103 |

| Total EGM losses | $56,673,722 | $19,402,885 |

| Range EGM venue annual losses | $516k-$13.65m | $2.5m-$8.56m |

| Loss per EGM | $135,486 | $90,761 |

| Expenditure per adult | $1,252 | $383 |

| EGMs/1,000 adults | 9.2 | 4.1 |

Notes: In 2015-16, Victoria had 509 club and hotel EGM venues, 320 of which were in Melbourne. During that financial year, $2.6 billion was lost on EGMs at these venues across the state, $2.06 billion in the Melbourne Metropolitan area. a Police-reported family violence rates are calculated using an aggregation of reports from the Victorian Crime Statistics and the 2016 Census population data. Reports include family violence-related: common assault, stalking, harassment and private nuisance, threatening behaviour, serious assault, breach of FV order, breach of FV intervention order. b Expenditure (or EGM losses) per adult and EGM density are calculated using 2015-16 VCGLR EGM data and the 2016 ABS Census population.

Participant codes

Quotes from participants reported in the results section are coded to provide anonymous context with reference to the site (1 or 2), study categorisation (person who gambled [G], significant other [SO], local resident [LR], Vietnamese local resident [LRV] or professional [P]) and gender [M] or [F].

3.2 Amenity and recreational facilities Site 1

Consistent with socio-economic data reported in section 3.1, Site 1 was described by many local resident participants as a traditionally working class and disadvantaged area. Researchers and participants observed indications of gentrification in this area, such as increasing real estate values, houses undergoing renovation, and council improvements to streetscapes and infrastructure such as lighting and building redevelopments. However, despite this, large industrial areas are located within Site 1, and enduring disadvantage remains apparent. Overall, Site 1 was described as lacking in a range of amenities.

Participants reported a lack of appropriate and accessible recreational and other facilities in the area:

It's boring always, all night, all day, doing something, especially those pensioners. 'Is there anything we can do not gambling?' Yeah, there should be an alternative [to EGMs]. (1GF)

There's not enough local parks, there's not enough meeting spaces … like there is a few hotels in the area. They're not necessarily what I would call family-orientated places … There's a lot of alcohol, a lot of gambling. (1SOF)

Public transport accessibility and safety were a concern for a number of participants in Site 1. Difficulties included living in areas not serviced by the local train network, limiting accessibility to activities for the whole family:

We don't even have an actual Metro train 15 kilometres from the city that stops at our station … we only have a V/Line train. So, we can wait around for a bus and they're talking about … taking away one of the bus services that runs past our street … Or, you wait for a V/Line train. On a weekend, there can be four hours between V/Line trains that stop at our station … it's really hard to send [teenage] kids off to do stuff on their own … a lot of the community centres in this particular council area are very spread out like that. So you need to be able to drive to get to these places. So, it's not - you can't just pack your kids off or if you don't have a car … whereas all pubs and clubs are actually quite easily accessible. (1SOF)

Many participants reported a need for improvements to accessible activities to support community cohesion:

They've got a culture day once a year … That's not enough for the whole community to get in … We've got a neighbourhood [house] around the … corner from my house. I've seen bugger all people there. Back in the day, the neighbourhood house would chuck odd street parties. Not just a street party, they'd have Santa come around, there'd be flyers left, right and centre, there'd be colour in the street … The world's so grey now … I reckon, around this whole Brimbank area … people need to see life. Not people dying, 'cause that's what it is in a pokie venue. It's death on the street … There's no footballs kicking around in the middle of the street. (1GF)

Some participants in Site 1 mentioned that there were great local Vietnamese restaurants and others acknowledged recent improvements to infrastructure such as parks, street lighting, bike paths, playgrounds and railway stations. However, there was a general lack of awareness about the facilities and activities available to residents:

I think nearly every local park I've seen has got new play equipment. And we go up to a park up in Sunshine North that has … new concrete paths and they've got a dog park there now. (1LR)

Many people aren't aware of [facilities available] … we've just built a $12m centre down in Braybrook. And [a] lady said to me one day, 'When's the hospital going to be finished across the road?' I said, 'It's not a hospital. It's a community centre with all the facilities for the community in the area and a library as well'. (1LR)

Problems associated with gentrification were also reported:

The process of gentrification again is not pushing people out, it's because people don't know where else to go now … At the same time, they see other people who are cashed up coming in and buying houses and the … the price of everything is going up across the board. (1P)

Participants in all categories (local residents, professionals, people who gambled and significant others) in Site 1 described awareness, or experiences of, crime and an overall sense of a lack of safety in this area. This contrasted with participants in Site 2 who overwhelmingly reported low crime levels (see section 3.3).

Some participants in Site 1 reported that the long opening hours of EGM venues allowed them to leave the house, and were often the only place in their community where they could go at night:

I'm very scared … for my safety and my daughter's safety … Some women got stabbed and killed on the [traffic] lights not long ago … people are not friendly anymore … anything can happen to you. (1SOF)

I'm scared … I don't go for walks anymore … When … you're home with your husband and if you're not getting along and … he's sitting watching TV, I'm here, not a word, no nothing, I might as well go out and I may go to the poker machines, where else do I go? (1GF)

A number of participants felt public transport in Site 1 was unsafe to use:

There's a lot of substance use, there's a lot of - you see a lot of violence around there. (1SOF)

Oh yeah, at the station, the new station. Not long ago, there was a stabbing there … People are not going, especially after dark. (1GF)

Concerns about public drunkenness and drug use were reported by residents and local professionals alike in the Site 1 area:

For years, you know, people have known it [EGM venue] to be … pretty rough ... especially at the moment … every Friday night … they're always in that park [across the road] fighting. (1GM)

Where I live there are drugs readily available. I know of the people that deal in our area ... I know who they are, I just keep out of their way. Look, where I live, I feel safe most of the time ... I often see people who seem to be on ice. From what I've heard described, people come, you know, close by our house and are affected by ice (crystal methamphetamine) because they've purchased it. (1SOF)

The Brimbank Council was running a series of community cultural events during 2015 to address concerns about safety. This included infrastructure improvements and local events such as an outdoor cinema in a local park and live music at the train station:

Sunshine's been fraught with danger and there is a lot of trepidation from the local population about wandering around at night. So … the place managers had organised to get the lighting improvements around the inner-city area. (1P)

A community professional involved in the campaign reported that it had some level of success but acknowledged that the underlying causes of crime and safety concerns would take time to address:

I don't think we completely shattered any notions about safety in Sunshine but we … made some impression that safety … is possible ... We had several touchy situations … at the bus interchange, there was … a group of people that would gather there every evening. Highly aggressive, always intoxicated or high on drugs [ice and other drugs]. Um, the police there constantly ... But again, police are overstretched. (1P)

There was a convergence of reports from many sources relating to crime at EGM venues, including armed robberies, drug dealing, stolen goods and money laundering. Gambling-related criminal activity in commercial venues is reported separately in section 4.2. Links between gambling, drug and alcohol use are reported in section 4.2 and section 7.1.

3.3 Amenity and recreational facilities Site 2

In contrast to these largely negative reports from participants in Site 1, participants in Site 2 spoke proudly of their local area and reported that people aspired to live locally as the area 'has got a lot going for it'. Also in contrast to Site 1, low crime levels in Site 2 were described as key to the area's liveability. This does not suggest that residents in this area haven't experienced crime or had safety concerns, but Site 2 participants did report a lower degree of concern about safety than Site 1 participants.

Overall, Site 2 was described by locals as 'well-established' with 'history', and a great 'variety of food and culture'. Participants reported their area as relatively spacious, characterised by areas with trees and green space. The Blackburn creek reserve was described as a great natural asset. Participants also praised the good 'public transport accessibility', and the local hospital was described as 'phenomenal' and 'fantastic'. Participants in Site 2 were in agreement that it is a desirable area to live and residents are well catered for:

I think these sorts of suburbs here are attracting people who are trying to move into, moving up the social scale. People are moving from the outer, outer suburbs to this area, the houses are expensive here now and they've always been just that little bit [better]. (2LR)

One participant described his use of the range of local sporting and exercise facilities:

Our local area is … quite well set up … we actually have a personal swimming pool but there's a [public] pool at the end of our street, which we can take our granddaughter to, where it has slides … We're heavily involved in cricket … I … usually go to every Victorian [football] match and quite often, a couple of interstate ones as well ... I have family who play golf, so there's a link with the golf club. (2GM)

Others in this area also reported participating in a wide range of activities locally such as attending private gyms, mountain biking, pottery, yoga and meditation:

We come to the local library almost every week. There's story time for little kids. The [council] run things like the Australia Day fireworks, they run the Christmas concerts … music sessions … I even went and did mindful parenting [course] … there are lots of things out there … And then, yeah, we pay for additional things on top of that. (2SOF)

Most participants in Site 2 were enthusiastic about the '[g]ood variety of great food and culture' (2LR) in their area. A number of participants also noted the convenience and suitability of local cafes for meals with children:

But there's so many other nice restaurants to go to than the pub … When you can go to a really nice restaurant here at Box Hill or Thai or whatever and get much more value for your money. And I'd rather have kids eating that food than, you know, parma and chips or whatever. (2SOF)

Observations of the local area made by the research team noted more pleasant streetscapes with electricity wires hidden underground and more open green spaces.

3.4 Geographic accessibility of gambling venues

High density of gambling venues in Site 1

Many participants in Site 1 reported that they found the high density of EGM venues in close proximity to their homes to be problematic, as they would end up attending these venues due to the convenience of their location rather than an intentional interest in gambling:

How many [EGM venues] I've got not far from me? I tell you. One, two, three, four, five. About six. It's only 10 minutes' drive. That's terrible ... Lot of them and they're in where the houses are and right where the neighbourhood is. (1GF)

There's a really high density of pokies in this area … it's terribly hard to go anywhere without the pokies, you know? (1LR)

Some described this saturation of gambling opportunities as predatory:

I'd say that maybe they've [operators] possibly targeted certain areas of Melbourne, assuming, 'Okay, this end is going to be more vulnerable, more desperate. This is where we can get our money back' … So, they've just gone … 'Okay, dump a whole lot of pokies there.' … I think they should have a restriction on the area, for the whole area … in poorer areas, they should have less. (1LR)

Accessibility of local venues is a major influence on visitation. People who gambled described how the venues were located in areas incidental to their everyday activities, and many described visiting venues to use bathroom facilities or for free tea and coffee facilities. Some participants would find themselves using machines without previously intending to:

I had family living right across the road from [Venue name 1] … [Venue name 2] was like on the way to the supermarket ... there's the venues if you're on your way to shopping and you look and, 'Oh I'll just go in there for a little bit'. (1GF)

One person who gambled described spending so much time at his local EGM venue that he used the venue's phone number as the place his mother's carers could contact him in the event of an emergency:

Because it was close to home and you know … especially the last couple of years of Mum's life … she was in a nursing home, we didn't know whether we'd be called, so we gave the nursing home our home address and the [Venue name]. (1GM)

Another person who gambled described the proximity to the local hospital where family were attending appointments as creating opportunities for him to gamble:

I lost $700 and I come back. My wife [in hospital], she didn't know nothing because I hid the [lost] money ... Oh many times. My wife, she had problem in hospital and my son too but I tried to get the time for me to go there [Venue name] half an hour, an hour. (1GM)

While some participants described visiting local Vietnamese restaurants as an enjoyable feature of the Site 1 area (see section 3.2), many participants reported often reluctantly attending EGM venues, in part due to the lack of other options for dining out:

We really struggled to go somewhere for a nice meal that doesn't have pokies … I would prefer it [an alternative venue], having a 12-year-old child, but every time we go in there, he's like, 'Can we have a gamble on the horses?' (1LR)

Some described that dining at a gambling venue might lead them to gamble unintentionally:

I mean if you go in and have a beer or a feed, you're going to go into the TAB or the pokies. (1GM)

I want to take the kids out to dinner over Christmas, you know? But they [EGMs] happen to be there … there's not a lot going on for the kids and I probably will get to the point where I need a break. There's no one to give me one, so, I will probably go to a pokie venue. Unfortunately. They're too fucking close. (1GF)

Venue accessibility in Site 2

Although there were far fewer venues in Site 2 (three venues), proximity to gambling venues was still a factor for some participants' gambling:

Basically, it's about nearness. It's [venue] near. (2GM)

Participants often reported visiting the venue closest to their house more frequently:

Yeah, it's the closest too. I can walk there. (2GM)

This person who gambled described the attractiveness of EGM venues as being that they are well maintained, clean and conveniently located on his way home from work:

Really just convenience and just having a bit of fun really and just spinning the wheel. It's kept very clean, yeah. I quite like that whole aspect and all that ... Coming home from work, it would definitely be on the way, yeah. (2GM)

Similar to reports in Site 1, close proximity of the local hospital to a venue in Site 2 provided gambling opportunities for hospital staff finishing their shifts:

Mum's a shift worker, she used to work at the Box Hill Hospital. So, she'll finish her shift in the morning, she'll go straight from work into the RSL, she'll stay there all day, [then] go and do her nightshift. (2SOF)

However, unlike Site 1, where participants reported a lack of alternative activities in which to engage, in this area some participants described a wide range of alternative activities that could be diverting from EGM use:

I read the local paper, I see lots of free events and different things that I would choose to go to rather than go out to a pokie venue. So, I guess it depends if there are things that might tempt people to do other things apart from go to that venue, potentially that might help. (2SOF)

The range of alternative social activities in Site 2 described by participants is discussed earlier in this chapter (see section 3.3).

Distance from EGM venues described as protective

The only 'dry area' of Melbourne covers about half of Site 2. While alcohol is available for purchase in this area, additional hotel, club or on-premises liquor licences can only be granted if approved by residents of this area. This has reduced the number of venues able to operate EGM licenses in the area. The existence of the 'dry area' indicates that where local communities have a decision-making opportunity - in this case, through a requirement to conduct a liquor license poll on each application - the harm-creating potential of dangerous commodities can be significantly reduced. This has led to a very different landscape of EGM accessibility compared to Site 1, as regulations stipulate that only those venues with a license to serve liquor can operate EGMs:

I mean if you're going to get in your car and go and drive there and it's a hassle and traffic and all that sort of thing, you tend to not … [My preferred pub is] in Auburn Road and, look, I love it down there because there are no machines, there's no betting, there's no TAB. I'm meeting up with a bunch of guys [tonight] that um none of them are into gambling at all. So, we'll just have a nice night … I'll buy a meal and a couple of beers and go home and I'll be very happy with that ... And there's no guilt trip, you don't wake up in the morning thinking you shit, I shouldn't have spent [that money on gambling] ... [Whereas] you can go to other places and have a beer and then bet on dogs … or feed 50 bucks into a machine and not get it back ... that night can cost you 150 bucks and tonight might cost me 50 bucks … If they're [EGMs] not around, you don't think about 'em. (2GM)

However, some people who gambled in Site 2 reported how a lack of other available venues with a liquor license in the area actually exposed them to EGMs at the local RSL club:

You go to the RSL because it's the only licensed place in Box Hill … You don't go to restaurants just because they've got a liquor licence, you go to the RSL. It's a substitute hotel … I would like Box Hill to have a proper hotel, no machines, because then you can sit and talk with friends, you can go out for a counter lunch without worrying about the machines in another room. (2GM)

Migrant experiences of gambling venues

Migrant participants in both sites reported that they were unaccustomed to the widespread availability of legal and commercial forms of gambling offered in Australia and noted the difference between the laws in their country of origin and Australia. In many other countries commercialised gambling is illegal:

I think it's different absolutely because … it is illegal in Vietnam [in a commercial setting]. (1LRV)

It [gambling] was not legal so there were no casino or no pokies or nothing else ... And when I first came here I just faced them for first time in my life. (1GM)

One South-Asian migrant described how she found herself in an EGM venue and felt a sense of shame in gambling, which is considered taboo in her culture of origin:

I went inside because I was curious … it's almost like a forbidden fruit that you're not allowed to take 'cause you're not allowed to see. And growing up, my parents [would say] 'All pubs are all full of drugs and alcoholics' … So, there were all these fears put into me. (1GF)

3.5 Summary

Participants in Site 1 described a lack of non-gambling facilities in their area, compounded by an overabundance of gambling venues. Gambling venues encourage a wide range of people to attend their premises by providing a wide range of facilities and activities, appealing to a broad demographic.

An earlier study (Rintoul, et al., 2013) identified a social gradient in expenditure on EGMs across the metropolitan Melbourne area. This study developed a regression model, which found 40% of the apparent effect of disadvantage was accounted for by machine density. The uneven distribution of venues between the two sites explored here highlights a structural inequity in the regulation and governance of gambling in Victoria. This uneven distribution of EGM availability is readily amenable to policy change and regulation.

Data from the census demonstrates that Site 1 is an area of higher socio-economic disadvantage compared to Site 2. VCGLR data shows Site 1 has more venues (eight vs three), with double the number of EGMs (416 vs 208; or 9.2 EGMs per 1,000 adults vs 4.1/1,000 adults) and losses of over $56 million per year vs $19.4 million in Sit 2. The findings presented in this chapter demonstrate how widespread availability of EGMs, as in Site 1, compounded by a lack of alternative recreational options, resulted in residents reporting that they reluctantly attended EGM venues.

The venues in Site 1 were described as being easy to access from home and offering a range of affordable food and drinks and other facilities, making them a main option for socialising when outside the home. This contrasts with evidence from Site 2, where a relative abundance of alternative social spaces and activities were combined with far fewer EGM venues. However, even in Site 2, where there are significantly fewer opportunities to gamble, people who gambled described difficulties in avoiding the use of EGMs in their local clubs.

Some participants in Site 2 reported that the co-location of EGMs with hotels is potentially problematic, in that it exposes those who were intending to meet for a social drink to machines when they may otherwise not have chosen to attend an EGM venue. Several people who gambled reported that they ended up using EGMs because they were available in the hotels or clubs they originally attended for social drinking purposes.

The requirement that EGM operators must have a liquor license in order to operate EGMs may lead some residents who may not otherwise gamble to use machines. This aligns with findings from the recent Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) report (Wilkins, 2017) that found that frequent drinkers were much more likely to gamble and to report gambling problems (Wilkins, 2017), indicating that the co-location of these activities may be problematic.

5 This study developed a geographic information system (GIS) of venue locations, losses and population data to predict vulnerability to gambling-related harm across Melbourne.

6 Victorian State suburb IRSD scores taken from www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/2033.0.55.0012016?OpenDocument

7 SEFIA IRSD Decile 1 is the most disadvantaged and Decile 10 the least disadvantaged.

4. Venue promotions, amenity and ambiance

It is illegal to directly promote EGMs in Victoria. However, indirect promotional strategies are customary, including free or subsidised meals and drinks and co-locating other activities at the venue in order to cross-promote gambling there. This chapter presents data about the ways in which venues promoted themselves in Sites 1 and 2. Also their effectiveness in encouraging residents to attend the venue (Bestman et al., 2016). Using the reports from local residents, it describes how venues embed themselves in local communities by providing spaces that may act to fill gaps in community amenity.

Participants reported on experiences in venues, including the range of activities available at these venues and the appeal of promotions, which influenced the way they frequented and used these spaces. Additional data about factors contributing to the characteristics of venues, including a range of illegal activities in and around venues, are also presented (see section 4.2).

The findings from the study are reported under the following thematic headings:

- cross-promotion of EGMs

- family-friendly venues

- free drinks, cheaper meals and food service to machines

- mood and ambiance

- illegal activities in or around venues.

These findings are reported together, rather than by site, as the promotional strategies were very similar across venues. For instance, one corporate entity operated three venues across both sites.

Participant codes

Quotes from participants reported in the results section are coded to provide anonymous context with reference to the site (1 and/or 2), study categorisation (person who gambled [G], significant other [SO], local resident [LR], Vietnamese local resident [LRV] or professional [P]) and gender [M] or [F].

4.1 Cross-promotion of EGMs

Participants in both sites reported receiving venue marketing and promotions, such as venue vouchers that could be redeemed either for food, drinks or on machines in the venue.

Participants in both sites also described going to venues for purposes not related to gambling; for example, to take advantage of free or subsidised meals and drinks, or to use toilets, carparking or other facilities offered by venues, such as sporting grounds.

One mother reported developing gambling harms from EGMs while attending a venue through her son's sport training, which is held at an EGM venue:

When [I] took my son to [sport facility provided at the venue] … it was cold … so I'd go in [to the venue] and have a cup of coffee. And then I wanted to wander around and see what else you can do. So, I went and had a look and to try [an EGM] and - I think I put $5 in one time. But then when you go Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturday for training ... Training goes for like two hours sometimes … Me being the single mum, I had to stay there … You can't make many friends … the one thing that got to me, was just having free tea and coffee. (1GF)

Several participants who gambled described using EGMs after initially visiting a venue only to use their bathroom facilities:

I'm a bit wary of … railway station toilets … If you've got like a club where you know the toilets are going to be clean ... you just walk in and you go, 'Oh whilst I'm here'. You feel a little bit guilty just using the loo and then walking out again … so you might put $10 in [an EGM] … It's an expensive way of doing it. (2GM)

Venue layout and the ambient sounds of the EGMs in the bar and bistro areas tempted some patrons who previously had no intention of gambling to use EGMs:

We'd have a counter lunch and a few beers and it was really good. But to get out of the hotel, you had to walk through the gaming room … And that'd be the trap. Because [friend] would say, 'Oh you know, let's put $20 in'. Rubbish. It'd be $200 by the time you'd leave ... you went to the bar and you'd start hearing the bells and whistles from the machines and, 'Oh well, let's go over'. (2GM)

Figure 4.1: Subsidised alcohol and live music promotion, Site 2

In Site 1, participants were more likely to report that heating and air-conditioning available in EGM venues made them attractive during different seasons:

They're nice and warm in there, they don't have to put the heater on [at home in winter] … Why go home anyway? I have to put the heater on … I might as well stay here. And you have coffee when you want it, then at 6 or 7 o'clock and savouries will go around … For that little piece of pizza … they will spend maybe another $100. They [venue] do it on purpose. (1GF)

A venue professional described the club's desire to increase crossover from the non-gambling spaces at the venue to the EGM gambling area:

We actually did a survey about … our bistro patrons and also of our junior [sport] players' parents and families … And there's only 8% of the families that actually play the pokies … And they're here, you know, a couple of nights a week for junior training and then they're here for games on the weekend ... And we did a survey of bistro patrons and about the same there … We get about a 10% crossover from bistro to games … I thought that was a bit on the low side [in terms of crossover]. (1P)

Figure 4.2: Venue promotions, Site 1

Figure 4.3: Promotions targeting a broad demographic (e.g. 'model waitresses' and a singing group) at EGM& venue, Site 1

'Family-friendly' venues

Participants in Site 1 found the provision of playgrounds and activities such as free face painting and free meal offers particularly appealing. They described attending EGM venues with children. This appeal is compounded by the lack of alternatives described by participants in Site 1, as documented in chapter 3. While there are no EGM venues with children's play areas in the immediate vicinity of Site 2, participants in both sites described the 'family-friendly' nature of EGM venues generally:

If it's school holidays and we've got them [children], there's not many places you can take special needs kids. So, we go [to EGM venues]. (1SOF)

Even though my children are not that young anymore, in the past that's a big pro if your children can have a little bit of a play … So very family friendly even though … through the glass wall you can see the pokies, nearly. So, it's very contradictory in that sense. (1LR)

Almost all participants who commented on this in both sites were concerned about exposing children to gambling:

A lot of these places have really low-priced meals and families will go there … and its impossible not to see the flashing lights. If you're a child, they're very quick, they pick up on anything that's like that and so it looks enticing right from the get-go. (2LR)

When describing a venue in Site 2, one participant felt the hotel environment was not one she would like to take her child regularly, especially when there were many other suitable places to visit in her neighbourhood.

Free drinks, cheaper meals and food service to machines

Many participants in Site 1 and some in Site 2 reported attending venues for the subsidised food.

Figure 4.4: Promotions targeting children at an EGM venue in Site 1

Figure 4.5: Seniors meal promotion, Site 1

However, some participants in Site 2 noted that the meals in this area were now expensive:

Now the local RSL, for example, you used to be able to get a massive counter meal for $7 or $8, now you go to the RSL and the pokies, that counter meal is now $32. (2P)

Vietnamese participants in Site 1 reported that gambling businesses ran specific promotions for their community:

On the Viet News newspaper. Every week, weekly paper, there are ads for the hotels and poker machines included, with some free services and free items. In Sunshine, it has the voucher so when you go there you can redeem the voucher for food. (1LRV)

On the whole, participants were cynical about many promotions such as loyalty cards and free meals:

They'd be getting it back in the pokies. Oh, for sure. I mean, there's never a free meal, is there? (2SOM)

I know it is nothing for free. They are after something else. (1LRV)

However, these marketing strategies were still reported to be effective. Many people who gambled responded favourably to free drinks:

A lot of venues give free coffees and that, which I appreciate. (1GM)

For some participants, promotions offered through club memberships were attractive, people who gambled described how these promotions encouraged them to use EGMs. For instance:

I park there. See, I parked there today [for free] ... they charge you $40 [per yearly membership]. And when it's your birthday, they give you a drink and they give you $30 worth of food. (2SOM)

Some venues were reported to provide free bus transport and subsidised meals for seniors' groups to encourage use of their gambling facilities:

They'd contact the groups and tell them they're going to organise buses for them … offer them … discounts on their meals and bring the crowd in and that's how they'd hook people in as well from this area to take them into town. And then the groups might make a couple of dollars on the deal. (1LR)

We're going on tours and they would take us somewhere to a buffet restaurant where all you can eat and then you gamble. So, you go and have a meal and then you go in to the machines and play the machines. (1SOF)

A number of professionals in Site 2 described how bus trips were often targeted to particular ethnic groups by some venues, including the casino:

Those groups were mainly aimed at Europeans, so, we'd try and hit the Greeks and Italians and Croatians and Spaniards and stuff. Because they're more social. So, they generally have more social clubs whereas the Asian market was predominantly ones or twos, most singles or double gamers ... They'd pay for their own bus but we'd provide them with a meal voucher, a drink voucher and $10 of gaming credit ... All bus groups, we were targeting pokie players ... You do the bus drop off at five and then the buses weren't allowed to go [back] … until nine 'cause that gave them time to have their free meal and drink ... [and] three hours to have a punt ... It's pretty well targeted. (2P)

And we found a lot of ethnic groups were ... getting on buses and going to casino and we actually - with the group's consent, surveyed some of their losses and they were amazed with how much the group had lost. And we're talking about people mainly on Centrelink payments ... And we had one group spend about $3,000. This was a bus of 50 people. The other one spent about - another one spent about $600 to $700 ... And the condition was that they had to stay within the casino complex for at least three or four hours. (2P)

The service of food and drinks to participants using EGMs was described as particularly problematic:

They're sitting there, they don't have to move ... During the football season I saw them wheeling around pies to people … I was like, are you serious? Like those people are not going to leave those machines … That's terrible. (2SOF)

If you're sitting there and you're winning 10 or 20 bucks or something and next thing this girl comes next to you, you know, she gives you a little paper plate with a couple of sausages and, you know, you've got your beer there or whatever or your glass of wine and 'ka-ching, ka-ching', you've got everything. Two hours later, something goes off. You know, number whoever machine's on, you've just won $100, you know. Oh great. They don't make you sit there for 10 minutes, they make you sit there for 10 hours. (2GM)

This matched researcher observations; for example, a coffee and cake trolley circulating at machines mid-morning was a scheduled weekly occurrence at some venues:

They wheel a cart around there to all the people and it has coffee and tea and biscuits and they don't have to move from their chair ... Like if they're thirsty, they have to get up off that machine and maybe that gives them a couple of minutes of not wasting their money and a couple of minutes is better than nothing. But if they're wheeling around coffee to people, nah [they won't move]. (2SOF)

Figure 4.6: EGM user served food while using two machines simultaneously

Some participants reported that draws, raffles, mystery boxes or other promotions happening at a venue would encourage them to stay longer and, in some cases, bet faster:

One of the things that does increase my gambling that the RSL does … [is] giving out tickets when you get certain combinations on your machine and then having a draw … If you're playing and, you'll have somebody calling out, and it'll be for like an hour or so and they'll say, okay if you get a king in each corner … put your hand up … and they give you like a little raffle ticket and then at the end of every 20 minutes or so they do a draw … It might be a grocery grab or something … I always have found that I bet faster, I play more to try and get whatever combination it is. (2G1F)

The Responsible Gambling Codes of Conduct indicate that people who gamble should not be encouraged to gamble for long periods of time. These industry-developed codes require staff to intervene when they observe a gambler demonstrating signs of problematic use of machines. However, researcher observations, combined with reports from people who gambled and professionals, demonstrated that codes were regularly breached in both sites. A full description of this issue is provided in an earlier paper (Rintoul, Deblaquiere, & Thomas, 2017).

4.2 Experiences at local EGM venues

Mood and ambiance

Venues were described by some participants as providing comfortable recreational and dining opportunities:

I think it was mainly - I think just cosiness, the lights, the relaxation of it all. Um but in the end it's not [relaxing]. (1GF)