Talking about parenting: Why a radical communications shift is needed to drive better outcomes for children

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

April 2019

Annette Michaux

A radical communications shift is needed to drive better outcomes for children. There is an opportunity for family welfare sectors to better understand parents’ attitudes to parenting to ensure that its messages reach parents. This article argues that communicators need to understand how parents think about parenting, and reframe their messages accordingly.

Key messages

- Common messages such as 'all parents struggle at times' or 'being a parent is hard' are counterproductive.

- Parents are much more responsive to messages that talk about parenting in the context of what is good for children.

- Avoid talking to parents about statistics or evidence. Use metaphor instead.

- The metaphor that works best with parents is one of 'navigating waters'. In it, parenting is journey where one may encounter smooth or rough seas, and where safe harbours and lighthouses offer respite.

Effective messaging to improve help seeking

When it comes to parenting, major gaps exist between what the research tells us and how the public generally thinks about this very important role. Experts know, for example, that a child's early years should be a critical focus of our collective attention. But, despite ongoing efforts, this focus is still not reflected in the public discourse on parenting. Experts also know that a complex interplay of factors influence parenting. In the public mind, however, a person's parenting history - how they were themselves parented - is a most pervasive and important influence.

These differences in understanding - and there are many more - are important because they get in the way of better outcomes for children. They may be a barrier to parents seeking help or undermine public support for funding and designing policy solutions and system supports around parenting.

Mapping the gaps

The Parenting Research Centre mapped these gaps through a commissioned research project (Volmert, Kendall-Taylor, Cosh, & Lindland, 2016) with the FrameWorks Institute - a US non-profit organisation that uses research to help other non-profits empirically identify the most effective ways of reframing social and scientific topics. Having articulated the problem, the research partnership asked 'what now'? How do we change these perceptions of parenting to achieve better results for children?

The result was Talking About the Science of Parenting (L'Hote et al., 2017), a second major research partnership to explore the path toward a more productive conversation around parenting in Australia. More than 7,600 Australians took part in this research, conducted by the FrameWorks Institute, and building on five years of communications research on child development.

The results were unequivocal: talking about 'effective parenting' doesn't work. This is because most Australians see parenting as an innate and individual pursuit rather than as something that is the responsibility of society more broadly. This is part of a nest of beliefs Australians hold on parenting that are influenced by culture. And these cultural models of parenting actively intercept well-intentioned messages around topics such as what works to build parenting skills, the need to fund parenting support and the importance of collectively improving parenting for the good of society.

Counterproductive communications

A common practice of policy and service communicators is to normalise the parenting struggle. This is a common device used by communicators to 'meet people where they're at', to connect with them and make them more receptive to messages. The research shows this to be ineffective. By normalising parenting challenges (e.g. 'all parents struggle at times', 'being a parent is the hardest job in the world') communicators risk making them seem inevitable - something that cannot be addressed or solved. This approach does not prime people to be more receptive to messages about parenting and should be abandoned.

This will be counterintuitive to many of those who communicate about parenting. But the outcome of communicating in these unproductive ways is a public that may disregard the facts and evidence we put forward and double down on existing beliefs and any misconceptions about parenting. This is surely not the result we seek. So, what might communicators do instead?

A clear way forward

The research findings give communicators a clear way forward to express their message more effectively. They show the need for a new 'master narrative' that focuses on the importance of child development - rather than the importance of parenting. This doesn't mean we stop talking about parenting. Rather, we need to talk about parenting in the context of what is good for children's healthy development.

'Reframing' communications from 'effective parenting' to 'child development' allows people to view parenting through a much more productive lens. In fact, communicating in this way switches on rich and productive ways of thinking about parenting and minimises the more dominant negative ways of thinking.

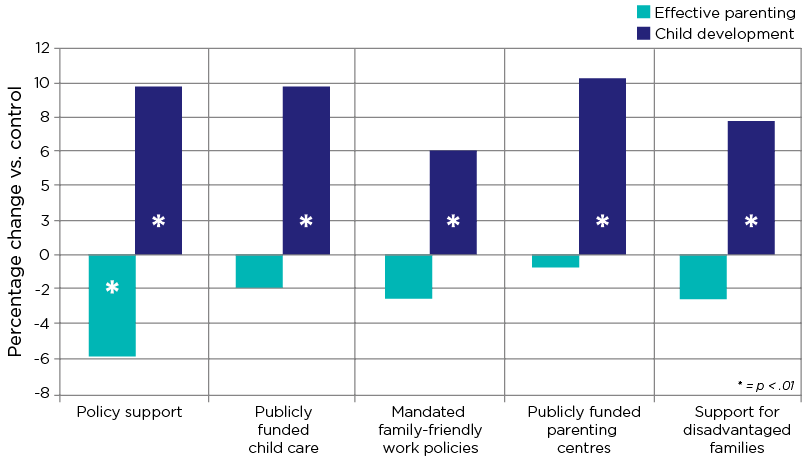

The research findings strongly show a marked change in attitude towards policy support for parenting when people are presented with scenarios via a child development frame as compared with an effective parenting frame. Figure 1 shows this difference in attitudes as compared to a control group when using the different frames. It's clear that the child development frame positively affects attitudes and support for the issues outlined at the bottom of the chart and the effective parenting frame negatively affects them.

Figure 1: Comparing attitudes to different framing, effective parenting vs child development

These findings have major implications for every organisation that communicates with and about parents and families. In particular, they have implications for the large investments made in public communications campaigns - often with precious and scarce resources.

The findings show that communicators need to think and talk differently about parenting in Australia if we truly wish to 'shift the needle' towards widespread acceptance about the importance of parenting support and what science is telling us about the critical role parenting plays in helping children to thrive.

Putting the evidence to work

What might this look like in practice? Employing this master narrative would be done as follows:

- Articulate the 'big idea' - child development and how parents can support it.

- Explain how it works and what threatens it.

- Explain what needs to be done - support parents to support children.

To explain what children's development looks like, how it works and what threatens it, communicators need to use meaningful language. Metaphor is a time-tested device that can be used to enhance the understanding of parenting concepts. But not all metaphors are equal. A key part of this research involved the testing of promising metaphors to help explain parenting.

Only one was shown to be successful in doing the job it set out to do - switch on productive ways of thinking about parenting and help people avoid unproductive thinking. The successful candidate was a 'navigating waters' metaphor. This describes parenting as a journey that requires skill and support, where one may encounter smooth or rough seas and where safe harbours and lighthouses can protect parents from these challenges.

Approaches to avoid and advance

As well as giving communicators an empirically tested metaphor to use in our work, the findings give some clear guidance about things to avoid and advance (see Table 1).

| Avoid | Advance |

|---|---|

| Rebutting or disproving ingrained ways of thinking about parenting | Telling a positive, consistent story about supporting child development |

| Talking about how all parents struggle and that parenting is 'hard work' | Start with children and their needs |

| Talking about improving parenting or pointing to 'effective' or 'good' parenting | Build understanding of child development and the support parents need to raise thriving children |

| Using statistics that show poor outcomes for children to argue for parenting support | Explain how circumstances affect parents and families using the 'navigating waters' metaphor |

| Starting communications with the idea of parenting skills | Focus on parenting skills after establishing how circumstances affect families |

| Talking about evidence-based parenting or the 'science' of parenting | Explain why parenting matters for childhood development |

Large-scale, cross-sector and cross-jurisdictional change is never easy - and that's what will be required if organisations are to succeed in translating these research findings into practice. However, there is commitment to change from the funding partners of this research: The Australian Department of Social Services, Victorian Department of Education and Training, NSW Government Department of Family and Community Services and The Benevolent Society. And the Parenting Research Centre will widely share the messages from this work.

With this evidence-based roadmap to guide communicators, we are in a prime position to effect real change for children and their families.

Further information

For further information and practitioner resources from this research, visit the Parenting Research Centre website or contact Annette Michaux at [email protected]

References

L'Hote, E., Kendall-Taylor, N., O'Neil, M., Busso, D., Volmert, D., & Nichols, J. (2017). Talking about the science of parenting. Washington DC: FrameWorks Institute. Retrieved from https://www.parentingrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Talking-about-the-Science-of-Parenting.pdf

Volmert, A., Kendall-Taylor, N., Cosh, I., & Lindland, E. (2016). Perceptions of parenting: Mapping the gaps between expert and public understandings of effective parenting in Australia. East Melbourne, Vic.: Parenting Research Centre and FrameWorks Institute. Retrieved from https://www.parentingrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Perceptions_of_Parenting_FrameWorks_Report_2016_web-lr.pdf

© GettyImages/StockRocket