Assisting families with ageing-related relationship issues

May 2019

Paula Mance

Relationship Australia trialled its Elder Relationship Service in response to a significant problem arising from the ageing of Australia's population: conflict within families around ageing-related issues.

Key messages

- As the population ages, families are dealing more and more with issues such as caring for elderly relatives and end-of-life decisions.

- These issues can cause conflict and even place elderly people at risk of violence and abuse.

- In response to the growing need of families with ageing related issues, in 2016 Relationships Australia piloted the Elder Relationship Services Pilot Program.

- The program has shown promise; however, it was found that client fees alone would not be sufficient to fund it: additional funding is needed.

Family relationships in an ageing society

In recent decades, demographic, health and social changes have resulted in the ageing of the Australian population and an increase in the complexity of family structures (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2008, 2012). These changes have the potential to increase ageing-related family relationship issues.

Ageing can contribute to poor family relationships in a number of ways. Older people with care requirements are predominantly looked after by their families. Longer life expectancies, coupled with extended ageing-related illness or disability, can significantly prolong the care phase. This, in turn, places significant mental, physical and financial burdens on older people, caregivers and extended family members (Millward, 1998; Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010). It also places older people living in vulnerable situations at increased risk of violence and abuse.

Where there are health issues and family care is no longer appropriate or available, or end-of-life decisions need to be made, relationships may become increasingly strained, particularly for families with complex structures, poor communication skills or histories of relationship dysfunction. Family disputes can affect interpersonal relationships far into the future, permeating burial arrangements, estate devolution and family interactions. These disputes affect the wellbeing of individuals, families and communities, and lead to increased costs to welfare and service systems.

Australians are also increasingly seeking legal avenues to solve their grievances, which can be emotionally and financially costly for individuals, families and the government (Australian Law Reform Commission [ALRC], 2016; Bagshaw, Zannettino, Wendt, & Adams, 2012; Conway, 2016).

The need for a new service

The current suite of family and relationship counselling and family law services has been successful in improving family relationships for a broad range of Australian families over the past decade; however, there is still a service gap in the suite of alternative dispute resolution services for older people and their families (Braun, 2013; Ellison, Schetzer, Mullins, Perry, & Wong, 2004).

In response to this service gap, in 2016 Relationships Australia trialled a new service targeted at families with ageing-related relationship issues. The aims of the Elder Relationship Services Pilot Program were to:

- prevent and resolve family conflict

- assist families to have difficult conversations

- help families with elder people to plan for the future

- support family members to resolve differences in ways that improve their relationships

- help families to make decisions that protect the wishes, rights and safety of members.

The program provided a range of services and supports including counselling, capacity building, support, information, education and supported referral to police or other specialist legal services. Where appropriate, it supported family meetings, often co-facilitated by a counsellor and mediator.

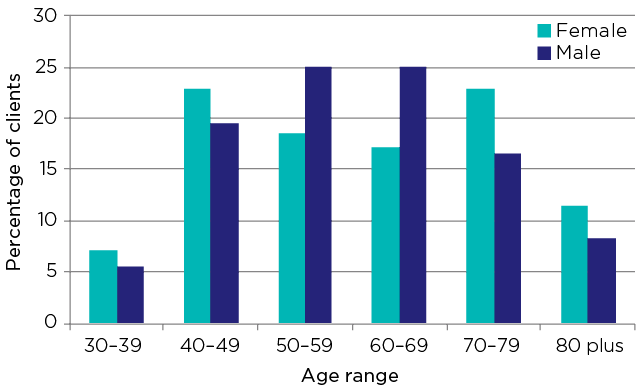

The program serviced 140 clients (Table 1). The age of clients ranged from 34 to 92 years. Just under two-thirds (65%) of clients were women (Figure 1). Half of the clients (48%) were older people, followed by adult daughters (30%) and adult sons (18%) (Table 2). Family meetings commonly involved one or more adult sibling and one or more parent.

| Counselling | Mediation | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Cases | Clients | Cases | Clients | Cases | Clients |

| Deakin, ACT | 16 | 18 | 9 | 17 | 25 | 35 |

| Wagga Wagga, NSW | 0 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| Launceston, Tas. | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 10 |

| Kew, Vic. | 2 | 2 | 19 | 49 | 21 | 51 |

| Adelaide, SA | 4 | 6 | 13 | 19 | 17 | 25 |

| Strathpine, Qld | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| Total | 27 | 33 | 52 | 107 | 79 | 140 |

Source: Relationships Australia administrative data, February 2017

Presenting issues

The most common presenting issue (58%) was family relationship problems, which included conflict, violence and abuse, poor relationships, disrespectful behaviour, poor communication and estrangement. Family relationship problems were evident in relationships between parents and siblings, and/or between sibling groups.

In 50% of cases, the presenting issue related to the future care or housing arrangements of a parent or parents. Where the care arrangement of parents was an issue, this was often compounded by family conflict, family violence, estrangement, and grief and loss.

Figure 1: Elder Relationship Services Program, client age by gender, as percentage

Source: Elder relationship service intake form

Family violence was identified as a presenting issue for one-quarter (24%) of clients, including violence perpetrated by older people, adult children and between members of sibling groups. The most common types of family violence were financial abuse, emotional abuse and, in a small number of cases, physical abuse. Family violence presentations could be divided into two categories: historical family violence that continued to affect the family into old age, with features of gendered family violence and power and control issues; and violence that resulted from increased vulnerability of family members due to ageing, and primarily involved financial abuse.

Mental health issues were identified as a presenting issue for 22% of clients, and grief and loss was identified as a presenting issue for 8% of clients.

| Relationship to older person | % |

|---|---|

| Self | 48 |

| Daughter | 30 |

| Daughter-in-law | 1 |

| Son | 18 |

| Son-in-law | 1 |

| Ex-partner or partner | 2 |

| Total | 100 |

Source: Elder relationship service intake form

Complex cases

As stated earlier, 58% of cases involved conflict, violence and abuse, poor relationships, disrespectful behaviour, poor communication and estrangement. The case notes below indicate the complex nature of presenting issues:

The family had a history of abuse. The father had assaulted the mother and had spent [time] in prison. Apart from the strain the abuse had put on the parental relationship, the relationships within the family, that is the siblings and their families, had been impacted by these events.

Throughout our client had kept in touch with each parent, supporting each with what s/he needed at the time, liaising with her siblings and keeping them informed with a view to allowing open communication channels. The client came to the service to:

- continue to find ways in which the family can support both parents

- continue to support the father in seeking counselling and/or undertaking appropriate anger management courses

- support parents to set up financially viable and independent living arrangements without having to go through a divorce and property settlement

- explore how to continue family relationships and hold family events in ways which are acceptable for everyone including the grandchildren.

In situations where there was identified elder abuse risk, at the root of the family's issues were often disrespectful behaviour and poor communication. In these situations, practitioners strove to resolve acute points of conflict and assist family members to have difficult conversations:

The service was contacted by an 81-year-old mother who was the carer for her physically disabled husband in a large home they share with their daughter, son-in-law and their three young children. The property was bought in the name of all four people some five years ago. The mother has some physical health issues of her own. She had been referred by a social worker who had been investigating possible alternative accommodation for them because the son-in-law had been saying that the home would have to be sold by the end of the year.

Individual intake and assessment was conducted with the parents together at an office not far from their home, and subsequently I saw their daughter and son-in-law. Both parents said that the mother was the target of verbal and emotional abuse by the son-in-law but there was no physical abuse or threatening behaviour. The mother said her daughter seemed to be heavily influenced by her husband's views but the relationship between mother and daughter was better when the daughter was on her own. Despite the stressful atmosphere in the house, the parents were still keen to discuss continuing to live under the one roof 'but with respect'. Seeing the grandchildren was obviously important to them.

At intake, the daughter and son-in-law seemed frustrated about a situation they say they had tried to improve but couldn't. They said they didn't know what would make the parents happy and had made many suggestions, including suggestions for respite care for the mother, but nothing was taken up. Communication was clearly a big issue. They were financially under great stress and the mortgage was blowing out in an unsustainable way.

The parties came together for mediation. Some agreements were made about finding a boarder, whose financial contribution could help with the mortgage, which the parents acknowledged was very urgent and important. There was also the opportunity for the mother to talk about how she felt about the abuse. The son-in-law listened and did not react defensively, which was helpful. Discussion also occurred about respite for the mother and the mother, in turn, talked about how much she loved them and the grandchildren. This was a productive session, and the discussion was respectful.

Conclusions

In our evaluation of the service, we found improvements in clients' knowledge and awareness of services, and in their communication, safety, behaviour and mental wellbeing.

The program was most effective if all relevant family members could be engaged and the older person was present. It was less effective if the service was unable to engage a family member who was significant to the family issue, there was long-standing entrenched family conflict, or if family members had already initiated a legal process (e.g. an application to an administrative appeals tribunal).

We found that the service could place more emphasis on holistic and therapeutic approaches, including supporting clients between sessions, and in exploring innovative ways to increase engagement with resistant family members. We also concluded that engagement with the service would improve via: phone calls to disengaged family members, rather than letters; face-to-face outreach at facilities and local offices; using influential family members to broker contact between disengaged family members; and increasing awareness of the service among potential referring organisations.

Overall, we found that the service was a natural fit with Relationships Australia's current business, workforce and service models. We also concluded that it was unlikely that the costs of service provision could be offset by client fees, especially if outreach was included, and that additional funding would be needed if the service was to continue beyond the short to medium term, or expand to additional locations.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2008). Family characteristics and transitions, Australia, 2006-07. Cat. no. 4442. Canberra: ABS.

ABS. (2012). Reflecting a nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012-2013. Cat. no. 2071.0. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC). (2016). Elder abuse: Discussion paper (ALRC Discussion Paper no. 83). Sydney: Commonwealth of Australia.

Bagshaw, D., Zannettino, L., Wendt, S., & Adams, V. (2012). Preventing the financial abuse of older people by a family member: Designing and evaluation older-person-centred models of family mediation. Final report. Adelaide: University of SA, Flinders University, Dept for Families and Communities, Office for the Ageing, Alzheimer's Australia, Guardianship Board, Relationships Australia and the Office of the Public Advocate.

Braun, J. (2013). Elder mediation: Promising approaches and potential pitfalls. Elder Law Review, 7 - Article 2.

Conway, H. (2016). Where there's a will ... : Law and emotion in sibling inheritance disputes. In H. Conway & J. Stannard (Eds.), The emotional dynamics of law and legal discourse (pp. 35-57), Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Ellison, S., Schetzer, L., Mullins, J., Perry, J., & Wong, K. (2004). The legal needs of older people in NSW. Sydney: Law and Justice Foundation of NSW.

Millward, C. A. (1998). Family relations and intergenerational exchange in later life (Working Paper 15). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Silverstein, M., & Giarrusso, R. (2010). Aging and family life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(5), 1039-1058.

© GettyImages/JakoVo