Playgroups evaluation guide

Planning for the evaluation of supported and community playgroups

Download Practice guide

Overview

This guide aims to encourage consistency in the evaluation of playgroups. However, due to the diversity of playgroup offerings and the variety of intended outcomes for playgroups, this evaluation guide does not propose one singular evaluation tool or methodology. It outlines the key steps and considerations in planning a playgroup evaluation, including evaluation design, selecting outcomes to measure and data collection methods.

Introduction

Playgroups are flexible and adaptable service offerings that aim to cater to the diverse needs of the participants attending them and the communities in which they are run. There is wide variation in both how they are run and who they are run for across Australia and, as a result, there are inconsistencies in how they are understood and evaluated. This evaluation guide is designed to be read in conjunction with Principles for high quality playgroups: examples from research and the Playgroup Principles, which articulates the key foundational principles that underpin high quality, effective playgroups.

Along with these resources, the evaluation guide aims to encourage consistency in how playgroups are planned, operated and evaluated, and consequently strengthen and build upon the current limited evidence base underpinning playgroups.

Due to the diversity of playgroup offerings and the variety of intended outcomes for playgroups across the levels of community, family, parents/carers and children, this evaluation guide does not propose one singular evaluation tool or methodology. The focus instead is on planning for a strong evaluation design that has the flexibility and elasticity to cater to the variability of playgroups (Dadich & Spooner, 2008), reflecting the differences in style, operation and the contexts within which they operate. It is intended, however, to bring a level of consistency to the evaluation of playgroups in order to build an evidence base to support their effectiveness.

Evaluation overview

What is evaluation?

Evaluation is something that we all do informally every day. We ask questions and make judgements and decisions based on the information we receive. Evaluation of a program simply formalises this through a systematic process of collection and analysis of information about the activities, characteristics and outcomes of a program with the purpose of making judgements about the program (Zint, n.d., citing Patton, 1987). Evaluation can take place at different times during a project for different purposes.

Why evaluate?

Evaluation serves two main purposes. Firstly, to determine whether or not playgroups are making a positive difference for children, parents/carers and families and secondly, to understand how and why a playgroup has worked (or not) and how it can be improved. Evaluation is also useful in informing decision-makers of ways to improve their playgroup offerings and in learning why things have worked or not worked (National Centre for Sustainability, 2011).

How can evaluation be used?

As well as helping to improve playgroups, evaluation can be used to make decisions about the allocation of resources and the continuation of programs. It can identify what the benefits associated with playgroups are, which participants' playgroups benefit most, and which conditions are necessary for these benefits to occur (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

What types of evaluation are there?

Broadly speaking, evaluations fall into the following categories:

- Needs assessment. A needs assessment is often undertaken as part of program planning to determine what issues exist in an area or with a particular group and what the priorities for action are.

- Process evaluation. Process evaluation is usually undertaken while a program is being implemented or at certain milestones within program implementation. Process evaluation provides information on how a program is working. It is usually used to improve a program and to see if a program is being delivered as intended (and, as such, if it is likely to achieve its outcomes).

- Outcome evaluation. An outcome evaluation looks at what has changed because of the program. It can be undertaken at the end of a program or at a particular stage (e.g., at the conclusion of a 12-week program or annually). The time frame will depend on the program (World Health Organization [WHO], 2013). See this Outcome Evaluation Plan template.

The playgroups evaluation guide focuses largely on outcome evaluation.

Key steps and considerations when planning for evaluation are outlined in more detail in the chart and each following chapter.

Figure 1. Key steps in planning an evaluation

1. Why do I need to evaluate?

The first thing to do when developing your playgroup evaluation plan is to consider how the evaluation will be used. What is the purpose of the evaluation and who is it intended for? For example, the evaluation may be a funding requirement. Your intended audience may be playgroup staff, managers who make decisions about the future of programs, or community members who have been involved in the playgroup. Each of these different groups is likely to want to know different things about the program. For example, playgroup staff may want to know whether playgroup participants are enjoying the activities, and program funders may want to know whether the playgroup is achieving its intended outcomes.

For CfC service providers one of the key purposes of undertaking an outcome evaluation will be to meet the 50% evidence-based program requirement, and the audience will include the Department of Social Services and Expert Panel staff from the Australian Institute of Family Studies as part of the program assessment process

2. What do I need to find out?

Evaluation design

The design of your evaluation will be determined to a large degree by the question(s) you are seeking to answer and the resources—time, money, staff, skills, etc.—that are available to you. The stronger the design, the more confidence you can have in the findings.1

When planning the evaluation design for your playgroups evaluation, Dadich and Spooner (2008) outlined six main questions to consider first:

- What are the outcomes of interest? Identify the processes or outcomes associated with your playgroup, and who or what the outcomes are relevant to (i.e., the children attending playgroup, the children's parents/carers, the families, their communities, or the organisations supporting or funding the playgroup). For the purposes of playgroup evaluation, you would usually measure short- or possibly medium-term outcomes. These are the ones that are likely to be directly related to your playgroup. Long-term outcomes are great to have but are often more aspirational and can be difficult to measure. See examples of short-, medium- and long-term playgroup outcomes in the Supported and community playgroup program logics.

- Why are these outcomes of interest? An understanding of what motivates the evaluation of your playgroup is important in your planning and may influence your choice of evaluation method (i.e., a funding body might be interested in different outcomes for parents/carers, families or communities).

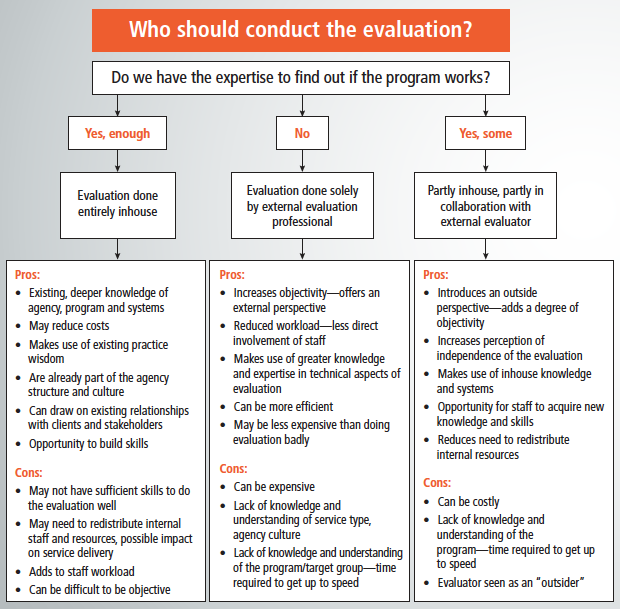

- How will the data2 be collected? Identify the most appropriate way to answer your research questions, taking into consideration the localised community-based nature of playgroups. What methods will be acceptable to your participants? Who is in the best position to collect the data? This may be a participant in the group, another individual who is familiar with the operation of the playgroup or an external organisation (see Figure 1 for more information on making a decision about who will conduct the evaluation).

- What are the most effective and efficient ways to manage the data? As most playgroup evaluations are undertaken with limited resources and time, make decisions early about the most effective and efficient way to manage the data to make sure the evaluation stays manageable and the material is meaningful and only accessed by the appropriate people.

- Who is the target audience? Identify who the evaluation is for to help inform the way you collect data and how you examine and present it. The target audience may be current playgroup participants (i.e., parents/carers or children), potential future playgroup participants, local services and organisations, or your funding body.

- What resources are available to support the evaluation? When planning your evaluation design, consider what funds and people are available to support the research. You may need to consider using external organisations and resources to support the evaluation of your playgroup or develop the skills of available staff. of available staff.

Figure 2. Decision tree: Who should conduct the evaluation?

Further resources

For further information about evaluating programs see Evaluation: What is it and why do it? <http://meera.snre.umich.edu/evaluation-what-it-and-why-do-it>

More information on approaches to evaluation can be found on the Better Evaluation website.

See Evaluation step-by-step guide for a guide on planning evaluation.

1 See Evidence-Based Practice and Service-Based Evaluation for further discussion of this issue.

2 Data can include, but are not limited to, observation notes, interview and focus group transcripts/results, survey and questionnaire results and information gathered from secondary datasets.

3. What will I measure?

Program logic

A program logic model is a living document that sets out the resources and activities that comprise the playgroup, and the changes that are expected to result from participating in the playgroup. It visually represents the relationships between the program inputs, activities and aims, the program's operational and organisational resources, the techniques and practices, and the expected outputs and effects.3 Other terms that are commonly used for models that depict a similar causal pathway for programs are theory of change, program theory and logic models.

The purpose of a logic model is to show how a program works and to draw out the relationships between resources, activities and outcomes (Lawton, Brandon, Cicchinelli, & Kekahio, 2014). The logic model is both a tool for program planning - helping you to see if your program will lead to your desired outcomes - and for evaluation - making it easier to see what evaluation questions you should be asking at what stage of the program.

A program logic is a critical element in program planning and evaluation because it sets out a graphic and easily understandable relationship between program activities and the intended outcomes of the program. A program logic is a "living document", that is, it should be reviewed regularly to see if it is still an accurate representation of the program or if it needs to be adapted.

What does a program logic look like?

There are many different types of program logics. We have developed examples of Supported and community playgroup program logics to illustrate the concept. These example program logics have been informed by the existing research evidence base, as well as input from playgroup professionals (as part of the broader Playgroups project) and are intended as a starting point from which to consider your playgroup's particular needs and intended outcomes. Each organisation will need to develop their own tailored program logic that is reflective of the playgroup and participants, and revisit it over time to make amendments as needed.

See How to develop a program logic for planning and evaluation for more information and a blank Program Logic Template that can be downloaded and used to develop your own outcomes-based program logic.

Selecting outcomes

If you have already identified the short, medium and long-term outcomes in your program logic, this makes doing an outcome evaluation much easier as you will have outlined what you need to measure and specified the time frames in which you expect those outcomes to be achieved.

Although you may have identified multiple outcomes for your playgroup in your program logic, evaluation requires time and resources and it may be more realistic to evaluate a few of your outcomes rather than all of them. When selecting which outcomes to measure, there are a number of factors to take into consideration. The following questions, adapted from the Ontario Centre for Excellence in Child and Youth Mental Health (2013), will help you to make these decisions:

- Is this outcome important to your stakeholders? Different outcomes may have different levels of importance to different stakeholders. It will be important to arrive at some consensus.

- Is this outcome within the playgroup's sphere of influence? For example, a community playgroup that focuses on improving child social and emotional development outcomes cannot reasonably be expected to have an easily measurable effect on secondary school completion.

- Is this a core outcome of your program? A program may have a range of outcomes but you should aim to measure those that are directly related to your aims and objectives. The Principles for high quality playgroups, Supported and community playgroup program logics and Playgroups outcomes measurement matrix have been designed to highlight core, fundamental outcomes of all playgroups and particularly those that would be a suitable focus for an outcome evaluation.

- Will the program be at the right stage of delivery to produce the particular outcome? Ensure that the outcomes are achievable within the timelines of the evaluation. For example, it would not be appropriate to measure a long-term outcome immediately after the completion of the program. It may be more appropriate to measure long-term outcomes at a national or jurisdictional level with larger organisational support and the use of larger-scale secondary datasets.

- Will we be able to measure this outcome? There are many standardised measures with strong validity and reliability that are designed to measure specific outcomes. The challenge will be to ensure that the selected measure is appropriate for and easy to administer to the target population (e.g., not a heavy time burden, not too complex, particularly important if your evaluation involves volunteers). See the Playgroups Outcomes Measurement Matrix for information on commonly used, reliable and valid measurement tools for measuring a range of child, parent/carer and community outcomes related to playgroups and CFCA resource Planning for evaluation II: Getting into detail.

- Will measuring this outcome give us useful information about whether the playgroup is effective or not? Evaluation findings should help you to make decisions about the program, so if measuring an outcome gives you interesting, but not useful, information it is probably not a priority. For example, if your playgroup is designed to improve parenting skills, measuring parental employment outcomes will not tell you whether or not your playgroup is being effective.

Evaluation questions

Once you have determined which outcome/s you will focus your evaluation on, you should form these into evaluation questions. Evaluation questions are the key things you want to find out about the playgroup and should be specific, measurable and targeted to ensure that you get useful information and you don't have too much data to analyse (Taylor-Powell, Jones, & Henert, 2003; WHO, 2013). When you are developing your evaluation questions, you should ensure that you will be able to find or collect data to answer the questions without too much difficulty.

For example, if the outcome is improved child development, it may be useful to narrow this to a specific domain of child development that can be measured more easily through pre- and post-testing. If you decide this domain is "social skills" then your evaluation question might be: "To what extent have children in the playgroup improved their social skills?"4

It is useful when conducting an outcome evaluation to include a question about "unintended impacts". Unintended impacts are things that happened because of your program that you didn't anticipate; they could be positive or negative. Finding negative outcomes can be just as important as positive outcomes, as it gives you some idea about what is working in your program and what isn't. It doesn't necessarily have to result in abandoning the program - instead, it is likely to inform what changes need to be made to the existing program to make it more effective.

Further resources

The Community Tool Box chapter 37, "Choosing Questions and Planning the Evaluation", provides more information on developing evaluation questions.

How to Develop a Program Logic for Planning and Evaluation (CFCA resource)

The Logic Model for Program Planning and Evaluation (University of Idaho, US). This brief article provides a good introduction to developing program logic models.

Introduction to Program Evaluation for Public Health Programs: A Self-Study Guide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US). This comprehensive guide covers the process of describing the program and developing a logic model, starting simply and building to more complicated forms.

Program Development and Evaluation: Logic Models (University of Wisconsin, US). An online, self-study module on logic models is provided on the site, along with templates and examples of logic models.

3 The outputs and effects can be immediate, short-term, medium-term or long-term. Because of limited resources, your evaluation may only be able to assess, for example, the immediate or short-term effects of your program. If that is the case, make it clear in your evaluation report that you are only assessing those particular effects, and why.

4 To take this to the next step, you may then note that the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire is a validated measure for increased social skills, and consequently explore the use of this tool for the evaluation.

4. How will I measure it?

Data collection methods

There are many collection methods to choose from, with differing degrees of scientific rigour that can moderate your capacity to attribute effects to the playgroup. The following is a discussion of some types of evaluation you can consider using to evaluate your playgroup.

Within the field of evaluation, there are established criteria by which evidence of the effectiveness or impact of a program or practice is assessed. These "hierarchies" or levels of evidence5 indicate the relative power of the different types of evaluation designs to demonstrate program effectiveness. If you are planning an evaluation, you can use these hierarchies to guide your decisions about which evaluation method to use. The hierarchies can vary but generally place randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or experimental designs at the top, followed by quasi-experiments, and then pre- and post-test studies (see the CFCA resource Planning for evaluation I: Basic principles for the pros and cons of these designs).

Your decision on how to evaluate your playgroup must be based on the needs of your playgroup, participants and community and the resources you have available to you. Your evaluation may also need to meet the specific requirements of your funding body. If you are a CfC service provider there are minimum requirements (see the CFCA resource Criteria for programs that can be included in CfC FP 50% requirement) that your playgroup evaluation must meet, for example a minimum number of participants (20) and pre- and post-testing of participant outcomes. See Box 1 for more information on pre- and post-testing.

Types of data

Qualitative research methods

Qualitative data typically comprise written or verbal responses collected via techniques such as interviews, focus groups, documents and case reports, but may also be derived from other media, such as photography or video. Qualitative data can reveal aspects of the participants' experiences of the playgroup and the social value of the playgroup (Dadich & Spooner, 2008). They can reveal a great deal about the complexity of participants' lives and the diversity of their views and experiences. They can also be used to complement or challenge findings from quantitative data, and provide insights into the subtleties of the program that may not be captured through quantitative methods (Stufflebeam & Shinkfield, 2007).

Observation

Observation involves the evaluator going out and visiting the playgroup and observing and measuring the behaviours of those who are of interest to the evaluation (e.g., parents/carers, children, facilitators, settings). The evaluator will take field notes while observing the playgroup and may also participate while observing (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011).

Box 1: Pre- and post-testing

In this commonly used design, factors relating to the objectives of the program are assessed prior to the program commencing and then at the end of the program to determine whether there have been any changes. For example, a supported playgroup aimed at improving carers access and referral to other services in the community would measure how many services carers access before they enter the playgroup. The same measures are taken again, in the same way, at the end of the playgroup (or in the more likely case of ongoing participation in the playgroup, at a pre-determined endpoint, say after six or 12 months of attendance). The difference between the two measures will indicate whether and how much change has occurred, and in which direction.

What's good?

- Pre- and post-test designs allow you to look for changes over a period of time and demonstrate that when a playgroup is provided to improve something, such as carers' parenting skills, that they actually do improve.

- They can be fairly simple to implement.

What's not so good?

- If you are gathering ideas from children, especially aged under 5 years, this design will be challenging due to their cognitive development. It is best used with carers (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011).

- With transient populations, a pre- and post-test design would require a large enough sample size that if families move on from the playgroup this doesn't cause a problem for the study (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011). This could be particularly relevant when evaluating intensive supported playgroups run in caravan parks, for instance.

- There may be other reasons (e.g., normal child development over time) why observed changes in behaviour occurred. Without a control group, you can't say definitively that the changes identified are due to your playgroup.

Observation has benefits in that it can be inexpensive and efficient, and provides access to information that is not easily collected through other methods; however, the success of this as an evaluation method is reliant on the skills of the observer to ensure that the data collected are meaningful and that the observation is undertaken in an ethical manner (see section 5 "Who will I collect data from?") (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011).

Interviews

Interviews are commonly used to gather qualitative information and are often semi-structured (in that questions may not necessarily be asked in a set order, or new questions may be prompted as the interview unfolds) (Alston & Bowles, 2003). Semi-structured interviews focus on a set of questions and prompts that allow the interviewer some flexibility in drawing out, responding to and expanding on the information from a participant. The interviewee's responses may be written down by the interviewer as the conversation progresses or recorded electronically. The recording may later be transcribed (although this can be costly if done by a professional transcription service). In-depth interviews may have little formal structure beyond a set of topics to be covered and an expectation on the part of the interviewer as to how the conversation might progress.

Interviews generally elicit rich data and can be used to shed light on data collected in the playgroup evaluation through other methods (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011). It is recommended that interviews are conducted and analysed by a skilled individual trained in this technique and independent to the playgroup (i.e., not the facilitator) to reduce the potential for any bias and enable participants to respond with positive and negative feedback.

Focus groups

A form of group interview, focus groups allow for information to be collected from several people at once in a much shorter time frame than if you conducted each interview separately. Thus, they can be a good way, when time and resources are short, to obtain both wide-ranging and in-depth information about a program from participants, managers and other stakeholders.

Interaction between participants can lead to high quality information but group pressure and dynamics may also lead to conformity or to some participants being less engaged in the dialogue. The focus group facilitator needs to ensure all members of the group have the opportunity to contribute, that all views are respected, and that the discussion remains on track.

Box 2: Evaluation methods for use in disadvantaged communities

Collecting data from parents/carers in disadvantaged communities can be challenging:

- parents/carers may be reluctant to provide information because they have concerns about confidentiality and anonymity;

- parents/carers who have poor English language or literacy skills may have difficulty participating in surveys, interviews and other data collection processes and parents/carers with low levels of literacy may have difficulty in responding to questionnaires and surveys; and

- parents may be having difficulties managing everyday stress that makes it hard for them to prioritise a task such as completing a survey or taking part in an interview or focus group.

Some measurement tools may be too intrusive for use in supported playgroups. Care must be taken to review the suitability of the measurement tool for use with disadvantaged groups to ensure that the administering of the questionnaire, for instance, will not damage the relationship the facilitator is trying to build with the families, prevent families from returning to the playgroup or impact the role of the supported playgroup as a soft-entry point to other services.

The following instrument and method may be more appropriate for use with playgroups in disadvantaged communities, although these are not strictly outcome measurement tools so consideration should be taken of what the aim of your evaluation is. They may be used in conjunction with other tools in order to provide a more complete picture of your playgroup participants' experiences.

Leuven scale

In response to the challenges of finding appropriate methodologies to use with disadvantaged communities you may consider using an observational tool such as the Leuven scale. The Leuven scale, or the Ferre Laevers' SICS (ZIKO) instrument, Well-being and Involvement in Care Settings: A Process-Oriented Self-Evaluation Instrumentis concerned with the child's wellbeing (how the child feels about the playgroup) and involvement (how deeply the child engages in the activities offered at the playgroup; Marbina, Mashford-Scott, Church, & Tayler, 2015). This scale uses a three-part process: (1) direct assessment of children's levels of wellbeing and involvement through a scanning of the group of children; (2) analysis of the observations; and (3) reflective discussion and action planning for improvements (Marbina et al., 2015).

Photovoice

Photovoice uses photos to give voice to disadvantaged communities such as children and youth in difficult circumstances, homeless adults and families and people with disabilities or mental health issues (Community Tool Box, 2016). It is used particularly for promoting community capacity-building and evaluating community programs (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011). Photovoice enables children and parents/carers to document their views about their playgroup and community through photos (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011).

Beginning with the training of users in photo-taking and establishing the playgroup as the focus of the photo-taking, the photos taken by participants are then compiled and used as a basis for discussion and reflection upon the participants' strengths and any concerns about the playgroup (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011). This process aims to promote dialogue with the participants and a shared understanding of the issues (Boddy & Cartmel, 2011). The photographs, and any artworks, are then presented to an audience (including policy-makers; Boddy & Cartmel, 2011).

Qualitative methods

What's good?

- Qualitative research methods are engaging and flexible (Dadich & Spooner, 2008), which is useful in the evaluation of playgroups considering their diversity and community-based, localised nature.

- Qualitative methods are good for understanding the ethos of the playgroup, drawing out the experiences of participants and understanding the social value of the playgroup (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

What's not so good?

- It is difficult to demonstrate how a playgroup has had a positive effect on participants through qualitative data alone. Using purely qualitative methods only may not generate the answers you require, and is generally recommended only where there is a clear rationale for not using a more rigorous evaluation method, or using both. For instance, if you have a small population size; there are no existing outcomes measurement tools that are appropriate for use with your target group; or you are evaluating a pilot version of the program (Goldsworthy & Hand, 2016), qualitative methods only may be more defensible.

- Qualitative evaluation methods can be time-intensive, requiring time for reflection and interpretation and, as such, often only involve a small number of participants. It is difficult to then attribute findings from small-scale qualitative studies to other playgroups (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

- Qualitative evaluations of playgroups may be relatively more subjective than those evaluations using quantitative methods (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

Further resources

For more information on the Leuven scale see Well-being and Involvement in Care Settings: A Process-Oriented Self-Evaluation Instrument <https://www.kindengezin.be/img/sics-ziko-manual.pdf>.

For more information on Photovoice see Implementing Photovoice in Your Community in the Community Tool Box.

See CFCA Practice Sheet Collecting data from parents and children for the purpose of evaluation: Issues for child and family services in disadvantaged communities for more information on collecting data from parents and children in disadvantaged communities.

See CFCA article Using qualitative research methods in program evaluation for more information on using qualitative research methods.

Quantitative research methods

Quantitative data are numerical and are typically collected through methods such as surveys, questionnaires or other instruments that use numerical response scales. There is some suggestion in the research that playgroups are associated with change either at an individual level (e.g., to the parents/carers' parenting confidence or the child's development), the family level or the community level (see the CFCA paper Supported playgroups for parents and children: The evidence for their benefits for more information on the effectiveness of supported playgroups). Quantitative research methods can be used to quantify the extent of this change (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

Surveys and questionnaires

Surveys can allow you to collect a lot of information in a relatively short period but unless you are using a validated and reliable tool (such as one of the outcome measurement tools listed in the Playgroups Outcomes Measurement Matrix) they require a great deal of planning and preparation, review and revision. Therefore, unless your playgroup has intended outcomes that cannot be measured by one of the tools listed in the matrix or another pre-existing valid/reliable tool, it is not recommended that you develop your own.

There are many tools that can be employed in your playgroup evaluation to quantify the amount of change that can be attributed to your playgroup. We have created the Playgroups outcomes measurement matrix to help you to find a valid and reliable tool to measure the outcomes of your playgroup. The outcomes measurement matrix considers a range of core playgroup outcomes related to parents/carers, children and communities and suggests some largely freely available, commonly used and appropriate tools through which to measure these. The matrix does not provide an exhaustive list of available tools, however, and you will still need to thoroughly assess any particular tool before you use it. Explanatory details about the instruments are provided in the matrix and it is recommended that you contact the developer of the tool to discuss your requirements.

Considering the diversity of both playgroup type and participant needs, you will need to choose the right measurement tool for your playgroup, and may need to consider adapting its use (in consultation with the developer and subject to copyright restrictions) to more appropriately suit your needs. Any amendments you make should not change the content of the items, because you might end up measuring something other than what you intended. The instruments decision tree (see Figure 3) sets out the decisions you may need to make about what tools you might use to gather the data.

If you are a Families and Children (FaC) Activity service provider and wish to record your client outcomes against the Department of Social Services Data Exchange SCORE (Standard Client Outcomes Reporting) methodology, the Families and Children Activity SCORE Translation Matrix will assist you to record outcomes, from a small selection of tools commonly used by service providers, into SCORE.

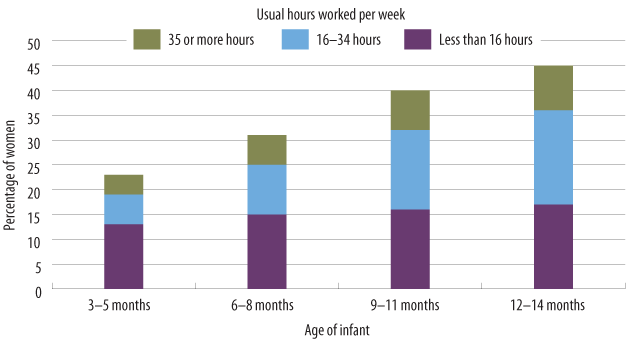

Figure 3: Hierarchy of evaluation designs and data collection methods

If you use an existing instrument, it is useful to check that participants who are likely to be attending your program understand the items. Cultural and language differences may lead to ambiguity and confusion. Testing of the items by people from various cultural groups can avert the loss of data (because the items are simply ignored) or avoid the collection of data that is inaccurate or misleading (because the questions are misunderstood; see Box 3).

Box 3: Case study: Empowering participants to engage with the evaluation process

Kids Caring for Country is a program based in Murwillumbah, New South Wales, that facilitates an Aboriginal All Ages Playgroup and After School Group out of which several other activities operate. The program is designed to empower participants to take an active role in determining program activities, including how the program is evaluated.

In approaching the evaluation process, staff were concerned that overly intrusive or culturally inappropriate evaluation tools would have negative effects on the ongoing trust and operation of the program. Responding to these concerns, program staff sought to empower parents and family members to engage with the process early on, beginning with evaluation design.

Staff started this process by introducing the need for evaluation to participants during regular Yarning Circle sessions, where staff asked for their input on the proposed evaluation tool, the Growth and Empowerment Measure (GEM). Staff discussed each question in the GEM with parents and carers, who were able to suggest changes to better represent their priorities of culture, family and spirituality. This process took several weeks, to ensure that all participants had a say in determining how their project would be more meaningfully evaluated. Proposed amendments were then presented to designers of the tool to ensure that its validity was maintained.

In planning for the evaluation survey, staff determined that a special workshop led by the family support worker and cultural advisor would be set up to facilitate a supportive group evaluation process. Participants, who were already familiar with the evaluation tool, were reminded about the workshop a week in advance, and a separate program for kids was run in parallel to allow parents and carers (including teenagers with caring roles) time to reflect on their experiences and emotional wellbeing and to complete the survey.

Source: Muir & Dean, 2017

Quantitative methods

What's good?

- Using quantitative research methods in your playgroup evaluation can mean that you're following a standardised data collection process (i.e., if using a valid and reliable outcome measurement tool). This creates consistency in the evaluation process and allows for comparisons to be made nationally (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

- Quantitative research methods may allow you to more easily demonstrate observed change in parents/carers or children and detail the number and type of participants.

What's not so good?

- Quantitative data alone may not allow you to accurately capture the complexity (Dadich & Spooner, 2008) of the families' experiences and interactions with the playgroup.

- Quantitative research methods may not demonstrate important contextual detail and are limited in their capacity to explain the processes that led to outcomes (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

- For statistical analyses to be meaningful they require relatively large sample sizes. It may not always be possible to recruit large sample sizes at the individual playgroup level, where numbers of participants are often small. In order for quantitative data to be meaningfully analysed, it may need to be collected from multiple similar playgroups, which may be possible if the evaluation is managed at an organisational or jurisdictional level.

Further resources

See the Research Methods Knowledge Base for more information on measurement.

See CFCA resource Evaluating the outcomes of programs for indigenous families and communities for more information on evaluating programs for Indigenous families.

For further guidance on choosing a valid and reliable tool and considerations for developing your own outcomes measure see CFCA resource How to choose an outcomes measurement tool.

For more detailed information on planning your evaluation see CFCA’s Planning for evaluation II: Getting into detail.

Mixed methods research

A single variable (such as parenting confidence) can be measured by a combination of both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection. This is called a mixed methods approach. Mixed methods research is defined as "research in which the investigator collects and analyses data, integrates the findings and draws inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches" (Tashakkori & Creswell, 2007, p. 3). In mixed methods research the qualitative and quantitative findings are typically integrated during the data collection, analysis or interpretation phase (Kroll & Neri, 2009).

Gathering different types of evidence by collecting both qualitative and quantitative data from various sources and combining different designs can improve the depth, scope and validity of the findings of the evaluation. For example, a quantitative survey or questionnaire may include one or more open-ended items that ask for a verbal or written (qualitative) response from a participant. Or a study of children's development in a supported playgroup might include observations of playgroup sessions (qualitative) as well as parent-reported responses to a questionnaire on child development (quantitative).

Being able to compare the data generated through different methods, for instance comparing what you hear during your qualitative interviews with participants with what you find from responses to your survey questions, enhances the validity of your evaluation findings (Bamberger, 2012). This triangulation of your evaluation findings will help identify consistency in your findings, and also highlight any inconsistencies and encourage you to further investigate the reasons behind the differences in findings (Bamberger, 2012).

Mixed methods

What's good?

- Employing a mixed methods methodology may give you a better overall picture of the effectiveness of your playgroup and the reasons why it may or may not be effective.

- Using both quantitative and qualitative research methods can assist in addressing the shortcomings (as discussed in the qualitative and quantitative research methods sections above) of using either methodology singularly.

What's not so good?

- Mixed methods research can be expensive in terms of resources and time to implement.

Data collection quality

The quality of data is determined by two main criteria, validity and reliability (see Box 4). Essentially, to ensure that you have quality data, you need to ensure that your data collection tools (such as a questionnaire) are taking an accurate measurement and are producing consistent results. The World Health Organization (2013) recommend three strategies to improve validity and reliability in evaluation:

- Improve the quality of sampling - have a bigger sample size, ensure that your sample is representative of the population you are sampling from.

- Improve the quality of data collection - ensure data collection tools have been piloted, that people administering the tools (e.g., staff doing interviews or overseeing the surveys) have been trained and that the data is reviewed for consistency and accuracy.

- Use mixed methods of data collection - qualitative and quantitative, and have multiple sources of data to verify results.

Some other important considerations to ensure your evaluation is good quality include:

- Cultural appropriateness. If you are working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people or people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, make sure your evaluation methods and the tools you are using are relevant and appropriate. The best way to do this is through discussion and pilot testing. See the CFCA resource Evaluating the Outcomes of Programs for Indigenous Families and Communities for more information.

- Thinking about who is asking the questions. If you have the same person running the program and conducting the evaluation, people may feel pressure to share only positive feedback. Consider how you can ensure anonymity for people participating in the evaluation, or have someone external run an evaluation session.

Box 4: Reliability and validity

Validity

A valid measure is one that measures what it is intended to measure. This may sound obvious; however, it can sometimes be difficult to achieve. For instance, clients' reports of their satisfaction with a behaviour change program are not a particularly valid measure of the effect it had on their behaviour - it may tell you that the client enjoyed the program but not whether it was effective in changing their behaviour. There are several types of validity that need to be considered. If you have used an established instrument, these are likely to have been addressed by the authors or otherwise documented in research articles where the measure has been used or discussed. If you have created a new instrument, then you will need to assess and report on its validity.

Reliability

A reliable measure is one that, when used repeatedly under the same conditions, produces similar results. For example, if nothing else has intervened, a set of weighing scales should give the same reading every time a one-kilogram bag of flour is placed on it. When dealing with measures of psychological constructs, it can be difficult to assess the reliability of a measure. If you are using an established measurement tool, you can refer to reports of its reliability in the research literature. If you are recording the occurrence of particular behaviours, having more than one observer recording and coding the behaviours offers a way to determine reliability - by comparing the level of agreement between the observers' ratings. However, thorough preparation and training of the observers and clearly defined categories of behaviour are required to optimise the inter-rater reliability of your data.

5 These have been the subject of much debate in recent years. See Donaldson, Christie, and Mark (2009) for a comprehensive overview of the debate.

5. Who will I collect the data from?

Sampling

Choosing who to include in your evaluation is called "sampling". Generally, most research and evaluation takes a sample from the population. For CfC service providers, the population is most likely all participants in the playgroup. If you are not including the whole population in your evaluation, then who you include and who you don't can affect the results of your evaluation. This is called "sampling bias" or "selection bias". For example:

- If you collect data from people who finished your program, but only 30 out of 100 people finished, you are missing important information from people who didn't finish the program. Your results might show that the program is effective for 100% of people, when in fact you don't know about the other 70 people.

- Similarly, if you provide a written survey to people in your playgroup but there are a number of people with poor literacy or English as an additional language, they may not complete it. Your evaluation then gives an incomplete picture of the playgroup - it only tells you whether it was effective for people with English literacy skills.

The number of people you include in your evaluation is called the "sample size". The bigger the sample size, the more confident you can be about the results of your evaluation (assuming you have minimised sampling bias). Of course, you need to work within the resources that you have, it may not be practical to sample everyone.

For CfC programs working to meet the 50% evidence-based program requirement, the minimum sample size is 20 people.

While it may not be necessary that everyone who is eligible participates in your evaluation, you need to consider who is being asked to participate and who is not, and the effect that this might have on the data that you collect and the conclusions you can draw from them.

You need to describe in your evaluation report who was invited to participate in the evaluation, why they were invited to participate, and how many people actually participated. If you think that there are implications from this (e.g., nobody with English as an additional language participated in the evaluation but they make up half of your program participants) you need to explain this in the evaluation report.

The Research Methods Knowledge Base has more information on sampling.

Ethical considerations

All research and evaluation needs to be ethical. There are a number of elements to consider when ensuring that your evaluation is ethical.

Risk and benefit

Before asking people to participate in your evaluation, you must consider the potential risks. Is there any possibility that people could be harmed, or experience discomfort or inconvenience, by participating in this evaluation? For practitioners working with children and families, potential for harm or discomfort would be most likely due to the personal nature of the questions. How can you ensure that this is minimised or avoided? Example solutions might include: questions being asked in a private space, having a list of services or counsellors that people can be referred to if required.

The potential for harm must be weighed against the potential for benefit. Often there are unlikely to be individual benefits for participants but their participation in the evaluation may contribute to improving your playgroup.

Consent

Participation in research and evaluation must be completely voluntary. You must ensure that people are fully informed about the evaluation: how it will be done, what topics the questions will cover, potential risks or harms, potential benefits, how their information will be used and how their privacy and confidentiality will be protected. You must also make clear to people that if they choose not to participate in the evaluation, this will not compromise their ability to use the playgroup now or in the future.

Written consent forms are the most common way of getting consent but this may not be suitable for all participants. Other ways that people can express consent are outlined in the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. If you intend to include children under 18 years old in your research, parental consent is nearly always required.

Evaluation with Indigenous participants

There are additional considerations when conducting research and evaluation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. For more information see the CFCA resource Evaluating the Outcomes of Programs for Indigenous Families and Communities.

Further resources

See CFCA Resource Sheet Demystifying ethical review for an overview of the process of ethical review for organisations evaluating their programs and CFCA article Ethical considerations for evaluation research.

6. How long will this take?

You may need to allow longer for evaluation than you anticipate. Planning for evaluation, ensuring enough time to recruit participants to your study, allowing time for outcomes to emerge, the data analysis and writing up the report all take time. To undertake pre-testing with participants before they begin a program you need to have everything organised. See the CFCA Outcome evaluation plan and sample evaluation timeline for examples and the blank Outcome evaluation plan template for your use.

7. What do I do with the data?

Data analysis

Time, skills and resources will be required to analyse the data you collect. If you are collecting qualitative data (e.g., through interviews) this will need to be analysed and sorted into themes. This can be very time-consuming if you have done a lot of interviews. Statistical analysis may need to be undertaken with quantitative data, depending on how much data you have and what you want to do with it.

For a good discussion of data analysis and the steps to data analysis and synthesis see the World Health Organization's Evaluation Practice Handbook, page 54.

Writing up the evaluation

Writing up the evaluation and disseminating your findings are important steps in your evaluation and it is important that you ensure adequate time and resources. You may be preparing different products for different stakeholders (e.g., a plain English summary of findings for participants) but it is likely that you will need to produce an evaluation report.

CfC service providers are required to submit an evaluation report as part of the 50% evidence-based program assessment process.

An evaluation report should include:

- the need or problem addressed by the program;

- the purpose and objectives of the program;

- a clear description of how the program is organised and its activities;

- the methodology - how the evaluation was conducted and an explanation of why it was done this way;

- sampling - how many people participated in the evaluation, who they were and how they were recruited;

- evaluation tools - what tools were used and when and how they were delivered (a copy of the tools should be included in the appendix);

- data analysis - a description of how data was analysed;

- ethics - a description of how consent was obtained and how ethical obligations to participants were met;

- findings - what you learnt from the evaluation and how the results compare with your objectives and outcomes; and

- any limitations to the evaluation and how future evaluations will overcome these limitations.

The World Health Organization provide a sample evaluation report structure in their World Health Organization's Evaluation Practice Handbook, page 62.

Challenges in evaluating playgroups

A challenge inherent in evaluating playgroups is the engagement of families in the evaluation process. For supported playgroups it can be a challenge to engage vulnerable or disadvantaged families. For community playgroups evaluation has the potential to place a considerable burden on volunteer playgroup conveners and could have the unintended consequence of dissuading some groups from either forming or continuing, or even registering as a playgroup through the relevant playgroup association (Dadich & Spooner, 2008). In volunteer-based community playgroups there may also be an additional issue of high turnover of participants, which may make it difficult to gather data over an extended period (Dadich & Spooner, 2008).

The evaluation methods outlined in this guide each have their limitations. A common challenge, for instance, in evaluating community-based programs is that without a randomised controlled trial, it can be difficult to clearly attribute any observed changes found in an evaluation to participation in the playgroup (Dadich & Spooner, 2008). Although not all of the methods outlined in this guide will demonstrate clear outcomes such as those found through randomised controlled trials, it is possible to design a strong study evaluating community and supported playgroups (Dadich & Spooner, 2008). Carefully selecting appropriate research methods to answer your evaluation questions will add strength to your evaluation (Dadich & Spooner, 2008) and be an important step in the process of building a stronger and nationally consistent evidence base for community and supported playgroups.

Resources

Supported Playgroups for Parents and Children: The Evidence for Their Benefits

Evaluation: What is it and why do it? <http://meera.snre.umich.edu/evaluation-what-it-and-why-do-it>

Families and Children Activity SCORE Translation Matrix <https://dex.dss.gov.au/score-translation-matrix-2/>

Implementing Photovoice in Your Community

Introduction to Program Evaluation for Public Health Programs: A Self-Study Guide

National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research

Program Development and Evaluation: Logic Models

Research Methods Knowledge Base

Research Methods Knowledge Base - Sampling

Well-being and Involvement in Care Settings: A Process-Oriented Self-evaluation Instrument <https://www.kindengezin.be/img/sics-ziko-manual.pdf>

References

- Alston, M., & Bowles, W. (2003). Research for social workers (2nd ed.). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Bamberger, M. (2012). Introduction to mixed methods in impact evaluation (Impact Evaluation Notes No. 3). Washington DC: InterAction and the Rockerfeller Foundation.

- Berry, S.L., Crowe, T.P., Deane, F.P., Billingham, M., and Bhageru, Y. (2012). Growth and empowerment for Indigenous Australians in substance abuse treatment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10(6), 970–983

- Boddy, J., & Cartmel, J. (2011). National early childhood care and development programs desk top study: Final report. Prepared for Save the Children. Brisbane: Griffith University.

- Community Tool Box. (2016). Chapter 3: Assessing community needs and resources. In Tools to change the world. Lawrence, KS: Work Group for Community Health and Development, University of Kansas. Retrieved from <ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/photovoice/main>.

- Dadich, A., & Spooner, C. (2008). Evaluating playgroups: An examination of issues and options. The Australian Community Psychologist, 20(1), 95–104.

- Donaldson, S. I., Christie C. A., & Mark, M. M. (Eds.). (2009). What counts as credible evidence in applied research and evaluation practice? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Goldsworthy, K., & Hand, K. (2016). Using qualitative methods in program evaluation. Retrieved from <aifs.gov.au/cfca/2016/05/24/using-qualitative-methods-program-evaluation>.

- Haswell, M., Kavanagh, D., Tsey, K., Reilly, L., Cadet-James, Y., Laliberte, A., Wilson, A, and Doran, C. (2010). Psychometric validation of the Growth and Empowerment Measure (GEM) applied with Indigenous Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44, 791–799.

- Kroll, T., & Neri, M. (2009). Designs for mixed methods research. In S. Andrew, E. J. Halcomb (Eds.), Mixed Methods Research for Nursing and the Health Sciences (pp. 31–49). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lawton, B., Brandon, P. R., Cicchinelli, L., & Kekahio, W. (2014). Logic models: A tool for designing and monitoring program evaluations. Washington, DC: US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Pacific.

- Marbina, L., Mashford-Scott, A., Church, A., & Tayler, C. (2015). Assessment of wellbeing in early childhood education and care: Literature review. Melbourne: Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority.

- Muir, S., & Dean, A. (2017). Evaluating the outcomes of programs for Indigenous families and communities (CFCA Practice Resource). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/evaluating-outcomes-porgrams-indigenous.pdf>.

- National Centre for Sustainability. (2011). A short guide to monitoring & evaluation. Community Engagement & Behaviour Change Evaluation Toolbox. Melbourne: Swinburne University.

- Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health. (2013). Program Evaluation Toolkit. Ottawa, Ontario: Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health. Retrieved from <www.excellenceforchildandyouth.ca/sites/default/files/docs/program-evaluation-toolkit.pdf>

- Stufflebeam, D. L., & Shinkfield, A. J. (2007). Evaluation theory, models, and applications. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J.W. (2007). Editorial: The new era of mixed methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 3–7.

- Taylor-Powell, E., Jones, L., & Henert, E. (2003). Enhancing program performance with logic models. Lancaster, WI: University of Wisconsin-Extention. Retrieved from < www.uwex.edu/ces/lmcourse/>.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). Evaluation practice handbook. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Zint (n.d.) citing Patton 1987. Evaluation: What is it and why do it? MEERA: My Environmental Education Evaluation Resource Assistant. Retrieved from <meera.snre.umich.edu/evaluation-what-it-and-why-do-it>.

Excerpts from this guide were originally published in:

- Planning for Evaluation I: Basic Principles;

- Planning for Evaluation II: Getting Into Detail;

- Demonstrating Community-Wide Outcomes: Exploring the Issues for Child and Family Services;

- How to Develop a Program Evaluation Plan;

- Evidence-Based Practice and Service-Based Evaluation;

- Evaluating the Outcomes of Programs for Indigenous Families and Communities;

- Using Qualitative Methods in Program Evaluation; and

- Collecting Data From Parents and Children for the Purposes of Evaluation: Issues for Child and Family Services in Disadvantaged Communities.

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable contributions of all those who participated in the development of the playgroup evaluation resources through the workshops, focus groups and online survey. The authors would also like to thank Playgroup Australia for their support, all those who provided feedback on the playgroup evaluation resources, Jessica Smart, Senior Research Officer at the Australian Institute of Family Studies for her contribution, and Elly Robinson, Executive Manager, Practice Evidence and Engagement at the Australian Institute of Family studies for her knowledge and guidance.

Featured image: © GettyImages/FatCamera

978-1-76016-140-8

Download Practice guide

Related publications

Principles for high quality playgroups: Examples from…

This document is intended to provide information on a set of principles that capture the essential core components of a…

Read more

Playgroups: A guide to their planning, delivery and…

A resource to assist in the development of high-quality and consistent playgroups

Read more