The effects of pornography on children and young people

An evidence scan

December 2017

Antonia Quadara, Alissar El-Murr

Download Research report

Overview

In 2016, the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) was engaged by the Department of Social Services to review what the available research evidence tells us about the impact exposure to and consumption of online pornography has on children and young people.

The increasing availability of pornography online has raised concerns about the impacts it may have on children and young people's:

- knowledge of, and attitudes to, sex;

- sexual behaviours and practices;

- attitudes and behaviours regarding gender equality;

- behaviours and practices within their own intimate, sexual or romantic relationships; and

- risk of experiencing or perpetrating sexual violence.

The purpose of this project was not to duplicate the considerable work undertaken by other researchers working on these issues (e.g., Flood, 2009; Flood & Hamilton, 2003a, 2003b; Sabina, Wolak, & Finkelhor, 2008; Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2007; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005). Rather, the purpose was to synthesise recent research and current approaches/interventions across this range of domains to inform future initiatives to reduce the negative impacts of pornography on children and young people.

Approach

Between August and October 2016, the research team reviewed the available research regarding:

- the effects of pornography on children and young people in relation to the issues listed above; and

- current approaches and interventions that have been developed to address the negative effects of pornography and support respectful relationships.

Research undertaken in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, the USA, Ireland, Scandinavia and Canada was prioritised. To varying degrees, the international contexts listed here share some similarities with Australia, such as political and legislative systems. However, the implications of the research are not fully transferable.

The literature was then synthesised to:

- draw conclusions about the key effects of pornography on children and young people and how this relationship between pornography and associated impacts is best understood;

- identify factors that might help explain or mediate the relationship between exposure to pornography and other "sexualising" materials and the impact on children and young people (i.e., risk and protective factors); and

- identify promising approaches to addressing this issue with children and young people, including key learnings.

Terminology used in this report

The term "pornography" is typically used across the academic and public policy literature as well as in popular and news media to describe sexually explicit material that is generally intended to sexually arouse the audience (Flood, 2016). This can be a useful shorthand; however, it is important to note that there is not a singular type of pornography. There is diversity in the form pornography takes (e.g., text, images, anime, video), its content (e.g., the sexualities and practices represented) and its production context. This variation is important to keep in mind when discussing the harms associated with online pornography, and it may make more sense to speak of "pornographies" to acknowledge this diversity. Some researchers have used the term sexually explicit material (SEM) and sexually explicit Internet material (SEIM) to refer to "online [pictures and] videos that depict sexual activities and genitals in unconcealed ways and are typically intended to arouse the viewer" (Hare, Gahagan, Jackson, & Steenbeek, 2014, p. 148).

At the same time, there is a dominant style and form of pornography that is easily accessible via the Internet, largely targets a male heterosexual audience and which makes up the majority of the global pornography industry (Crabbe, 2016). Arguably, it is this form of pornography that is animating contemporary discussions about the harms associated with exposure to and consumption of online pornography.

In this report, the terms "pornography" and "online pornography" are predominantly used to encompass:

- textual, visual and audio-visual sexually explicit material that is generally intended to sexually arouse the audience;

- mainstream, dominant forms of pornography; and

- pornographic material that is uploaded, accessed, shared and downloaded via online platforms.

Caveats

There are several caveats for the reader to keep in mind:

- The literature reviewed was limited to empirical and other research published as academic, peer-reviewed publications or research reports published in non-commercial form available online (i.e., grey literature).

- The search strategies limited searches to:

- research published between 2005 and 2016; and

- literature published in English in Australia and relevant international contexts: Canada, NZ, the USA, the UK, Ireland, and Scandinavia.

This means that research studies published after 2016 have necessarily been excluded and that traditional research studies have been privileged. These research studies often lag behind the issues practitioners, educators and others are seeing in their work.

Report structure

The report is structured in two parts. The first part provides a synthesis of the literature and its implications for developing initiatives to address the harms associated with online pornography. The second part presents a review of the literature informing the synthesis report.

The evidence library collated and used in this project is provided as a separate attachment to the report.

Key messages

-

Nearly half of children between the ages of 9-16 experience regular exposure to sexual images.

-

Young males are more likely than females to deliberately seek out pornography and to do so frequently.

-

Pornography use can shape sexual practices and is associated with unsafe sexual health practices such as not using condoms and unsafe anal and vaginal sex.

-

Pornography may strengthen attitudes supportive of sexual violence and violence against women.

-

Pornography and its impacts need to be situated within a broader framework of primary prevention and supporting the sexual safety and wellbeing of children and young people.

In this part, we synthesise what the research literature tells us in terms of:

- how children and young people are exposed to or consume online pornography;

- the nature of harms associated with this exposure and/or consumption; and

- the diverse factors that may mediate these harms.

The implications are then considered for designing and implementing initiatives that aim to address the harms associated with online sexually explicit material. The methodological approach used to undertake the review is described in Part B, the review of the literature.

Understanding exposure to and consumption of online sexually explicit material

Before describing the research findings themselves, the following key points are important.

First, "pornography" as a social issue or problem is both profoundly private and profoundly political. Desire, sexuality, sexual arousal, masturbation - these are deeply personal experiences. At the same time, pornography has also been a source of intense political, legal and philosophical debate about censorship, civil rights, moral standards and values, sexual freedom, protecting children, gender politics, sexual objectification and violence against women. Diverse political and ethical viewpoints influence understandings about the effects of pornography on children and young people and how this is best addressed.

Second, the advent of Web 2.0 has significantly changed how people communicate, connect and share information. Web 2.0 shifted the World Wide Web from a static repository for information into a dynamic site of interaction, enabling social networking and other peer-to-peer and participatory online platforms (Thomas & Sheth, 2011). The World Wide Web is now characterised as:

- personalised;

- interactive;

- convergent and interconnected;

- user-driven; and

- highly mobile.

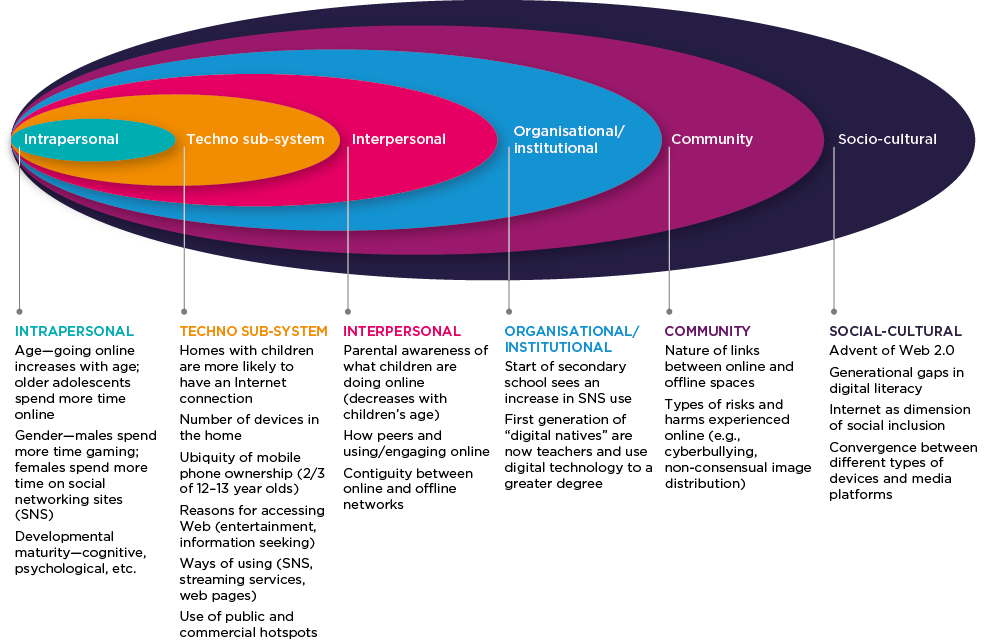

This is the contemporary landscape into which young people have been born. It is a landscape that, as many commentators have noted, affords both opportunity and risk (Livingstone & Brake, 2010). These technological developments have also occurred within, and are shaped by, intersecting spheres of influence, namely:

- the intrapersonal (i.e., the individual);

- the interpersonal (family and peers);

- organisational and institutional settings (such as schools);

- community contexts; and

- the broader socio-cultural context.

Figure 1 provides a visual mapping of the research literature in relation to these spheres of influence.

Figure 1: Socio-ecological context shaping access/exposure to online pornography

Finally, sexual violence - perpetrated particularly against women and children - is highly prevalent both in Australia and internationally, as demonstrated in Box 1. There has been a long-standing examination, from the 1980s to the present time, of whether and in what ways consumption of pornography facilitates sexual violence perpetration. Overall, pornography's "causal attribution" has not been demonstrated. This does not mean, however, that there is no connection. Indeed, the growing evidence base on preventing violence against women and children by addressing its underlying determinants or conditions invites us to look at:

- the messages mainstream online pornography generates about gender, equality and (hetero)sexuality; and

- how these messages might shape the attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of children and young people in forming respectful, equitable romantic/sexual/intimate relationships.

Box 1: Sexual violence

Victimisation

- People aged 19 years and under make up 60% of all sexual assault victims.

- Girls and young women aged between 10 and 14 years experience the highest rates of sexual violence in Australia.

- Twenty-nine per cent of all male sexual assault victims are aged between 0 and 9 years.

Perpetration

- Sexual assault offences perpetrated by children and young people aged between 10 and 19 years old increased by 36% from 2012 to 2014.

- Girls and young women aged 10-17 years made up 58% of all recorded offences committed by females from 2012 to 2013.

- Boys and young men aged 10-17 years old committed 16% of all recorded sex offences from 2012 to 2013.

Sources: ABS, 2014 & 2015; Warner & Bartels, 2015; CASA Forum, 2016.

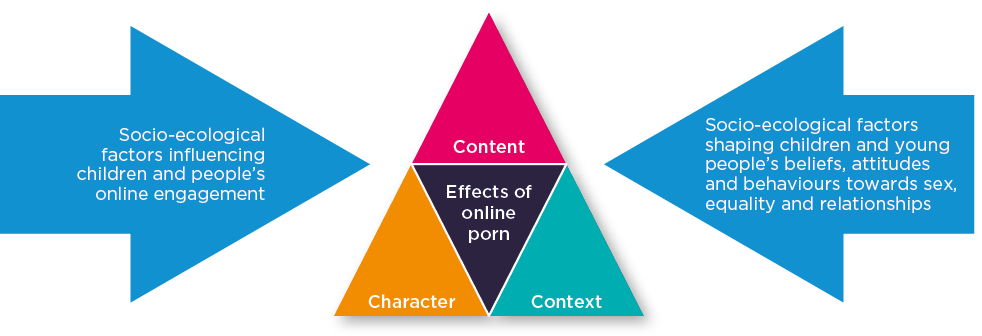

In short, understanding the impacts of pornography on children and young people must start with situating pornography, its consumption and its impacts within its broader sociocultural context. As represented in Figure 2, key dimensions of this include:

- Digital communication technologies, platforms and practices in general. For example, what is the role and significance of technology in the lives of children and young people? How is it used for education, social connection, exploration, entertainment? How does this change over different developmental stages? What are the practices and values within children and young people's environments about technology use?

- The range of online risks children and young people experience. For example, what are the dynamics and prevalence of cyberbullying, exploitative relationships and connections online? How aware are parents, guardians and educators about the types of harms that can be experienced online?

- Social scripts and discourses about men, women and sex, such as "once aroused, men cannot control themselves", "women say no when they mean yes", "women often play hard to get", "it's men's role to pursue women", "women need love to have sex, men need sex to feel love", "men physically need sex", "women don't know what they want sexually until a man shows them".

- The broader determinants of sexual violence and violence against women, such as rigid stereotypes of masculinity and femininity, gendered inequality regarding decision-making and resources in private and public life, male peer relationships that condone aggression, and minimizing, excusing and rationalising violence against women.

Figure 2: Situating pornography and its impacts as an issue

Findings from the literature

Contexts of exposure to and consumption of pornography

As Figure 1 makes clear, the accessibility of and exposure to pornography is located within a number of contexts and can therefore occur through a variety of mechanisms. The key themes from the national and international research literature on exposure to and consumption of pornography are that:

- Exposure is highly likely to occur. In Australia, just under half (44%) of children aged 9-16 had encountered sexual images in the last month. Of these, 16% had seen images of someone having sex and 17% of someone's genitals. Images of this nature were more likely to have been seen by adolescents rather than younger children. More recent results from the UK report that 53% of 11-16 year olds have seen online pornography at least once, with the vast majority having viewed pornography before the age of 14.

- Exposure can be inadvertent or intentional. Inadvertent pathways to exposure include searching for sexual health, relationships or medical information online and pop-up ads. Intentional could include being sent links to follow and intentional searching.

- The extent and frequency of viewing pornography differs by gender, with males more likely to deliberately seek out pornography and to do so frequently.

- Attitudes and responses to exposure also varied by gender, with females having more negative views and responses such as shock or distress compared to males, who are more likely to experience pornography as amusing, arousing or exciting, particularly in older cohorts. Negative feeling tends to decrease with repeated viewing (though it is unclear why this is the case).

- Parents overestimate exposure for younger children and underestimate the extent of exposure for older children (again, it is not clear why this is the case).

Two key types of research have been undertaken to examine whether and in what ways consuming pornography is harmful:

- Experimental studies aim to test - physiologically, psychologically, cognitively - participants' responses to viewing pornography. These have been criticised for being artificial in that it's not known how pornography use occurs and is incorporated within everyday life.

- Correlational, naturalistic studies aim to understand how pornography use occurs and is incorporated within everyday life. These are limited because they are unable to test causal directions between pornography and impact. There are a few longitudinal studies that are able to provide information about changes over time.

Despite the limitations of the research methodologies, there is an emerging consistency in what pornography can influence and in what ways. These are:

- knowledge, awareness and education about sex including sexual practices, sexual health and sexual behaviours;

- attitudes, beliefs and expectations about sex;

- attitudes, beliefs and expectations about gender;

- sexual behaviours and practices;

- sexual aggression; and

- mental health and wellbeing.

Table 1 summarises the key findings from the research.

In sum, exposure to and consumption of pornography can have a range of associated effects. While some of these, such as more permissive attitudes and beliefs about sex (e.g., accepting attitudes about casual sex), knowledge about sexual practice and sexual practices themselves (such as anal sex, sex with multiple partners) may not be inherently problematic, the most dominant, popular and accessible pornography contains messages and behaviours about sex, gender, power and pleasure that are deeply problematic. Physical aggression (slapping, choking, gagging, hair pulling) and verbal aggression such as name calling, predominantly done by men to their female partners, permeate pornographic content (Sun, Bridges, Johnson, & Ezzell, 2016). In addition, this aggression often accompanies sexual interaction that is non-reciprocal (e.g., oral sex) and where consent is assumed rather than negotiated.

The following section synthesises what the research suggests about factors that mediate these harms.

| Knowledge, awareness and education |

|---|

|

| Attitudes, beliefs and expectations about sex |

|

| Sexual behaviours and practices |

|

| Attitudes, beliefs and expectations about gender |

|

| Sexual aggression |

|

| Mental health and wellbeing |

|

Factors mediating these harms

In line with the points above, pornography consumption is one risk factor among others. For example, using violent pornography has been linked to actual aggressive behaviours, including sexual assault. This shows that the content (what types) of pornography being accessed matters. There is also evidence that one's pre-existing understanding of sexual norms (what kinds of sexual activities are appropriate) affects how distressing exposure to pornographic material depicting other kinds of activities is. This is especially applicable for younger children. Both age and cultural context make a difference in the effects of sexually explicit materials. How minors read pornographies also produces different effects, for example if they think that pornographic representations depict realistic or unrealistic sexual behaviour. All of these factors interact with each other differently, and in particular tend to have different effects for boys and girls of different age groups, making gender and age important points of interest.

Table 2 highlights some of the important factors that affect the reception of, engagement with and potential effects of pornography. These are grouped under the following headings:

- Character/Individual factors: personal characteristics that affect the reception of, engagement with and effects of pornography;

- Context: situations in which pornography is viewed that make a difference to how it is understood; and

- Content: the substantive content of the pornographic representation.

| Character | Context | Content |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Overall, the key points from the evidence are:

- Mainstream, online pornography can have a range of negative effects on knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about sex and gender; sexual practices; mental wellbeing and the risk of sexual aggression.

- These negative effects are mediated by the interaction between individual characteristics; the contexts in which exposure and/or consumption occur; and the content of the pornography itself.

- The mediating factors of individual characteristics, context and content are themselves situated within a generally interconnected, interactive and mobile digital world as well as a socio-cultural context that is not gender equal, and in which stereotypical beliefs about women, men and sex are common.

Summary of issues

Taken together, the research findings suggest that the key issues underpinning the harms associated with pornography relate to the following and how they interconnect:

- the cumulative effect of attitudes, knowledge, practices plus the scripts and narratives of contemporary pornography in which aggression, objectification, roughness, non-reciprocity and assumed consent to all practices and partners is the default expression of hetero sex;

- the location of this pornography within our broader cultural context, in which stereotypes about gender, sexism, sexual objectification and violence supportive attitudes are also at play across the social ecology in addition to normalising young men's pornography consumption itself; and

- the absence of alternative narratives, scripts and representations of heterosexuality, women's sexual agency and desire that meet the developmental and information needs of children and young people.

An important implication arises from this: the harms associated with pornography consumption needs to be considered at both the individual and collective levels.

At the individual level, there are a range of risk factors associated with consuming pornography that make some males more "predisposed" to sexually aggressive behaviours, such as hostility towards women, lower intelligence, antisocial tendencies and a higher interest in impersonal sex and domination (Malamuth & Huppin, 2005; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005):

When examined in the context of multiple, interacting factors, the findings are highly consistent across experimental and nonexperimental studies and across differing populations in showing that pornography use can be a risk factor for sexually aggressive outcomes, principally for men who are high on other risk factors and who use pornography frequently. (Kingston, Malamuth, Fedoroff, & Marshall, 2009, p. 216)

At the collective level, the three issues listed above essentially create an "echo chamber" for the sexual socialisation of children and young people, particularly males. As Sun and colleagues noted in their study:

[Our] findings build on the work [of others' research] illustrating the relationships between pornography use and male consumers' attitudes and beliefs about real-world sexual relationships. We, too, find that pornography is not mere fantasy or an individualised experience for men. Instead, our findings are consistent with a theory suggesting that pornography can become a preferred sexual script for men, thus influencing their real-world expectations. (2016, p. 8)

This means that initiatives to address the negative effects of pornography need to also address these intersecting issues. This is examined in the following section.

Figure 3: Summary of key influences on pornography's impact.

The implications arising from our analysis is that pornography and its impacts need to be situated within a broader framework of primary prevention and supporting the sexual safety and wellbeing of children and young people. This involves continuing to develop an integrated prevention framework based on a public health approach to prevention of sexual harm, violence and abuse that draws on the insights of child development, situational crime prevention and prevention education (Quadara, Nagy, Higgins, & Siegel, 2014), as well as on the more tertiary responses such as legal and regulatory strategies.

The following sections outline interventions and initiatives that have been implemented nationally and internationally.

The most recent Australian Government intervention has been the Senate inquiry into the harm being done to Australian children through access to pornography on the Internet, which released four recommendations in November 2016. The Senate committee recommended:

- dedicated research into the exposure of children and young people to pornographic material, mainly with regard to online pornography;

- the creation of an expert panel comprised of professionals from a range of fields to provide policy recommendations to the Australian Government;

- a review of state and territory government policies on responding to allegations of peer-to-peer sexual abuse in schools and training materials for teachers and others who work with children and young people; and

- an Australian Government evaluation of information available to parents/caregivers and teachers regarding online safety and risks, including a review of the website of the Office of the e-Safety Commissioner.

Other Australian Government and non-government services have taken steps to reduce children and young people's exposure to online risks - including pornography - and enact harm minimisation strategies.

Three key types of intervention were identified:

- legal and regulatory avenues to existing legislation regarding online pornography;

- education for children and young people; and

- education and resources for teachers and parents.

This section provides an overview of government and non-government interventions, paying particular attention to those aimed at parents/caregivers and teachers. The first section describes the three interventions listed above and looks at examples of each, including interventions pertaining to technology-facilitated sexual violence. The second section focuses mainly on resources available to parents/caregivers and an overview of the advice put to them about mediation and communication - two of the key techniques used in negotiating children and young people's experiences of online pornography. The third and final section provides an overview of the resources available to teachers, and discusses the whole-of-school approach that sees schools as a key setting in ensuring the healthy sexual development of children and young people.

Legal interventions

The Enhancing Online Safety for Children Act 2015 (Cth) was implemented in Australia to oversee the management of issues regarding children and young people's digital activities. Part of its function was to establish the Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, an independent statutory office designed to provide "online safety education for Australian children and young people, a complaints service for young Australians who experience serious cyberbullying, and address illegal content through the Online Content Scheme" (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016). The Online Content Scheme restricts access to illegal and offensive material using the measures provided by the National Classification Scheme (RC, X18+, R18+, MA15+), and the Office of the e-Safety Commissioner has the power to remove illegal or offensive content under the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 (Cth).

Technology-facilitated sexual violence

Some argue that "more needs to be done both within and beyond the law" to address the effects of technology-facilitated sexual violence (Funnell, 2015; Henry & Powell, 2016, p. 398). The critique of legal interventions draws attention to the lag between technological developments and legislation to manage technology-facilitated sexual violence (Powell & Henry, 2016b). Indeed, in 2016, only Victoria and South Australia have specific legislation pertaining to the management of the non-consensual distribution of intimate images. New South Wales (Australian Associated Press [AAP], 2016), the Northern Territory (Poulson, 2016) and Western Australia (Government of Western Australia, 2016) have announced plans to implement such legislation, while Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory, and Queensland have not indicated their intention to enact such legislation (see Table 4).

| State/Territory | Specific legislation for technology-facilitated sexual violence |

|---|---|

| Victoria | The Crimes Amendment (Sexual Offences and Other Matters) Act 2014 (Vic.) introduced new sections pertaining to the distribution or threat of distribution of an intimate image, extending the Summary Offences Act 1966 (Vic.). |

| South Australia | Current: Summary Offences (Filming Offences) Amendment Act 2013 (SA) introduced a new section pertaining to the distribution of an invasive image into the Summary Offences Act 1953 (SA). Recently introduced: Summary Offences (Filming and Sexting Offences) Amendment Bill 2016 |

| Tasmania | None |

| New South Wales | Pending |

| Australian Capital Territory | None |

| Northern Territory | Pending |

| Queensland | None |

| Western Australia | Pending |

In terms of Commonwealth legislation, s 474.17 of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) pertains to telecommunications offences, which could potentially be used to charge offenders for crimes including the non-consensual sharing of intimate images. Further, Commonwealth legislation can also be used to charge perpetrators with offences related to child pornography, if the intimate image depicts an individual under the age of 18 (Attorney-General's Department, Submission 28: the phenomenon colloquially referred to as "revenge porn", 2015). The Enhancing Online Safety for Children Act 2015 "has authority to communicate to websites or social media services that are hosting harmful material and require the removal of that material" (Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Reference Committee, 2016, p. 39). Researchers, legal experts and social service workers generally support more specific Commonwealth legislation to provide legal definition and federal management of this important issue (Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Reference Committee, 2016). Other legal strategies include the Australian Cybercrime Online Reporting Network, which has processed approximately 489 online complaints about the non-consensual sharing of intimate images since its establishment in 2014 (Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Reference Committee, 2016).

In addition to legal interventions, the Commonwealth Government recently pledged an extra 10 million dollars to manage domestic violence in Australia, including the provision of support for victims of technology-facilitated sexual violence (Cash & Porter, 2016). The funding comes from the overall budget for the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022. The government funds are expected to "improve research and education to counter the risk of technology-facilitated abuse by ensuring women's privacy and safety are protected and young people understand the impact of their actions" (Cash & Porter, 2016). Specifically, the funds are intended to combat virtual violence by:

- establishing a complaint and support line whereby victims can report revenge porn and access immediate and tangible support; and

- providing young people with information and education about pornography and its social effects (Cash & Porter, 2016).

Specific training for those working in the criminal justice sectors is required to develop best practice management of technology-facilitated sexual violence and ensure legal remedies are effective. Ongoing professional development is important and has already been implemented in organisations specifically providing legal and/or support services to women (Powell & Henry, 2016; Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Reference Committee, 2016). Specialist training to police officers is particularly important for their work in supporting victims to report and follow through with cases (Powell & Henry, 2016; Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Reference Committee, 2016).

Education for children and young people

There are several key education resources in Australia aimed at primary and secondary school aged children and young people (listed in Table 5). The list includes some resources that may not directly refer to online pornography but could be adapted in different ways to provide such information to children and young people.

| Resource | Author(s)/Organisation | Age group(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Resilience, Rights and Respectful Relationships | Department of Education and Training (DET) (Vic.) | Foundation to level 12 |

| Catching on Early: Sexuality education for Victorian primary schools | Department of Education and Training (Vic.) | Primary school |

| Catching on Later: Sexuality education for Victorian secondary schools | Department of Education and Training (Vic.) | Secondary school |

| The Practical Guide to Love, Sex and Relationships *Includes a video and lesson plan about pornography - Porn: What you should know - for students in year 8 and above | The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University (Vic.) | Secondary school |

| Building Respectful Relationships: Stepping out against gender-based violence | Department of Education and Training (Vic.) | Secondary school |

| In the Picture: Supporting young people in an era of explicit sexual imagery * Includes resources to support a whole school approach to addressing pornography's influence | Crabbe, M./ Reality & Risk Project | Secondary schools; community organisations |

| It's Time We Talked, website | Crabbe, M. & Corlett, D./ Reality & Risk Project | Young people; parents; schools; community organisations |

| Love and Sex in an Age of Pornography, broadcast documentary film | Corlett, D. & Crabbe, M./ Reality & Risk Project | General broadcast audience; rated MA15+ |

| The Porn Factor, broadcast documentary film | Crabbe, M. & Corlett, D./ Reality & Risk Project | Parents, teachers, youth workers and others; rated MA15+ |

| Fightback: Addressing everyday sexism in Australian schools | O'Keeffe, B. & the Fitzroy High School Feminist Collective | Secondary schools |

| Tackling Sexual Harassment | Australian Human Rights Commission | Levels 9 and 10 |

The national school curriculum begins teaching children about bodies, boundaries and relationships at a foundational level, prior to years 1 and 2 (i.e., 6 and 7 year olds). The national curriculum provides schools with teaching resources that cover a variety of topics relating to sexual health, developing bodies, respect, safety and identity (Australian Curriculum Assessment & Reporting Authority, 2016). The scope of that education expands at secondary school level to include sexual relationships, and encourages students to reflect on their experiences of the media and its influence on personal attitudes, beliefs, decisions and behaviours (Australian Curriculum Assessment & Reporting Authority, 2016).

The most recent resources are the Resilience, Rights, and Respectful Relationships materials for schools in Victoria. This resource provides social, emotional and sex education for children and young people from foundation to year 12, covering the following eight topics in an age-appropriate manner:

- Emotional literacy;

- Personal strengths;

- Positive coping;

- Problem solving;

- Stress management;

- Help-seeking;

- Gender and identity; and

- Positive gender relations.

Foundation level up to level 6: Gender, social and emotional skills education is provided but, as with other Victorian school curriculums, education regarding sexual relationships (including discussions about pornography) doesn't start until levels 7 and 8.

Levels 7-8: The resource offers information and activities regarding gender, gender identity, gender-based violence and the use of technology and media platforms for gender ideologies, with a view to assist in the development of critical literacies and promote positive relationships. Topics covered include:

- Health impacts of gender norms;

- Gender-based violence;

- Pornography, with a focus on critical readings of gender and power; and

- Sexting, with an emphasis on legal issues.

Levels 9-10: Activities are included to develop social and emotional skills, which are noted as providing an entry platform for positive gender relationships education, particularly with existing programs such as the Building Respectful Relationships: Stepping out against gender-based violence program (levels 8, 9 & 10).

Levels 11-12: Activities and detailed information for the topics of gender and identity and positive gender relations are included.

Subsections of the gender and identity topic include:

- Exploring gender stereotypes;

- Gender literacy and gender norms;

- Masculine and feminine gender norms;

- Privilege and gender; and

- Gender equity.

Subsections of the positive gender relations topic include:

- What is gender-based violence?;

- Attitudes associated with gender-based violence;

- Asserting standards and boundaries in relationships; and

- Pornography, gender, and intimate relationships.

The final subsection defines pornography as "a vehicle for communicating and shaping norms within gender relationships, particularly when that pornography also incorporates acts of violence against women" (Department of Education and Training, 2016, p. 105). The materials suggest to teachers that the following issues may be covered in group discussions:

- "increased aggression on the part of the man and extreme acts causing discomfort to women partners;

- women partners having to look pleased by these acts;

- women partners having to please men partners;

- forced viewing of pornography via texting or social media;

- influence of pornography on what men think should happen between them and their partner;

- the belief that pornography reflects real life sexual situations;

- emotional manipulation to ensure compliance;

- lack of discussion and education options for young people;

- normalisation of pornographic acts;

- misrepresentation of what is enjoyable;

- access to pornography before access to trustworthy, quality sex education;

- potential effects on younger children; and

- predominant use of pornography by men and boys." (2016, p. 105)

Digital and sexual literacies

Digital literacies and exposure to explicit online content may cause children to develop sexual literacies in different ways to previous generations, particularly in response to pornography as contemporary sex education for children and young people (Crabbe, 2016; Fileborn, 2016; Flood, 2016). Two key reports are drawn on here to contextualise the role of parents/caregivers and teachers in children and young people's digital and sexual literacies: The High-Wire Act report (2011) and the Talk Soon Talk Often guide (2012). The Talk Soon Talk Often guide, in particular, offers advice to parents/caregivers who may be unsure of how to communicate to their children about sex. It draws attention to the fact that although parents/caregivers may not broach such topics, children have already started "learning some important messages that will lay the foundation of their sexual development" from contexts other than the family environment (Walsh, 2012, p. 6). It suggests that there are four main contexts in which children and young people develop early ideas about bodies, relationships, sexualities and gender:

- home;

- school life;

- screen time; and

- online relationships.

Talk Soon Talk Often encourages open communication between children and parents in a similar way to the It's Time We Talked online resource, which states that, "young people say their parents, particularly their mothers, are their most trusted and used source of information regarding sexual matters" (Reality & Risk Project, 2016). Similarly, schools have been named a key setting with an important role to play in ensuring children and young people make sense of their exposure to online pornography in healthy ways. The High-Wire Act states: "Schools are optimally placed to support students to be cyber-safe. Raising the awareness of young people before, or as, computers are introduced into the curriculum can be a preventative step - ensuring young people are better equipped against the risks they are likely to encounter online" (Cyber-Safety, J. S. C. o., 2011, pp. 40-1).

Critical thinking

It's Time We Talked specifically asks young people to question pornography, stating: "Seeing porn might seem normal. But what does porn say? Who makes it and why? And what does it all mean for you?" (Reality & Risk Project, 2016). Asking such questions encourages viewers to reflect on the messages contained in online pornography and works to foster discussion while respecting the agency of the young people involved. That is an important alternative to the construction of young people as passive actors in their consumption of online pornography.

Arming children and young people with tools to engage critically with media is important to their understanding of the differences between online pornography and their offline sexual relationships. It's Time We Talked provides advice to that effect:

We need to teach young people to "read" imagery and to develop the sorts of frameworks that allow them to understand and critique what they're seeing. They need to understand that media is often created to promote something as desirable and necessary and, at the same time, communicates a whole range of other messages - about, for example, power, gender, class and culture. (Reality & Risk Project , 2016)

Resourcing parents/caregivers

Parents/caregivers are encouraged to educate themselves about the Internet and social media in order to be aware of the current online dangers and opportunities facing their children (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016; Think U Know, 2016). Parents/caregivers are less likely to be intimidated by online risks if they are informed and take an active role in their children's digital lives (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016).

The Think U Know (2016) resource stated that "understanding how young people use the Internet and what they enjoy doing will help you to recognise any suspicious or inappropriate behaviour. It will also help you to talk with your child about their online activities if they think you understand the online environment".

The Office of the e-Safety Commissioner offers practical, technical advice for parents/caregivers to give their children, for example:

- instructing children "to leave or close the page immediately or minimise the screen if they are worried about the material they have seen (hit Control-Alt-Delete if the site does not allow you to exit)";

- teaching children "not to open spam email or click on pop-ups, prize offers or unfamiliar hyperlinks in websites";

- advising children to "report offensive content to the site administrator (for example use 'flag' or 'report' links near content)" (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016).

Other advice for parents/caregivers generally falls into two categories of harm minimisation, mediation and communication. A combination of the two offers an effective strategy for ensuring minimal rates of exposure to online pornography, as well as assisting children and young people to make sense of their experiences (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016; Reality & Risk Project, 2016; Think U Know, 2016). Mediation includes strategies such as installing filter software to reduce the likelihood of risk exposure (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016; Think U Know, 2016). Tools to support communication consist of "how to" guides for parents/caregivers to discuss online pornography with their children, in addition to frameworks for encouraging critical reflective skills in children (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016; Reality & Risk Project, 2016; Think U Know, 2016). Such communication also strengthens the trust relationship between parents/caregivers and children, which has been described as a protective factor in children's health and wellbeing (Katz, Lee & Byrne, 2015). Additionally, a trusting parent/caregiver-child relationship is key to supporting disclosures of negative online experiences should they occur (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016).

Mediation

The Office of the e-Safety Commissioner cautioned parents/caregivers, stating: "you can teach your child strategies about how to deal with offensive material but be vigilant, especially if your child is prone to taking risks or is emotionally or psychologically vulnerable" (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016). Parental controls are essential in harm minimisation strategies including risk exposure with regard to online pornography (Childnet Int., 2016). Listed below are the major mediation tactics that parents/caregivers employ to prevent risk exposure and ensure age-appropriate online activities.

Filtering

Parents/caregivers are encouraged to use filtering software as a way of managing children's Internet access (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016; Think U Know, 2016). Filtering is available through Internet service providers as well as through individual websites, and can be adjusted according to the user's age. For example, websites such as Google and YouTube provide options for adults to enable filters in order to regulate searchable content.

Filtering works well on household computers as well as on sole-use computers belonging to children and young people. However, the changing nature of children and young people's Internet access from laptop or desktop computers to smartphones makes filtering online content much more challenging (Ofcom, 2015). The Think U Know (2016) resource offers links to information about parental controls, stating that they can "allow you to restrict what content can be accessed" on smartphones and tablet computers. Further, Think U Know states that limiting online access will "ensure that your children are only able to access age-appropriate material" as children require parental permission to access unknown websites.

Rule setting

Most resources encourage rule setting, and both schools and parents/caregivers are advised to sign contracts with children and young people that set out terms of their appropriate Internet use (Think U Know, 2016). Think U Know (2016) offers parents a downloadable "Family Online Safety Contract" and states:

It's important to remember that many of the behaviours and issues we experience online are no different to those we experience in the "real" world. This means our expectations around behaviours should also apply online. It's a good idea to speak with your child about your family values and how this extends to behaviour online. One way to encourage this discussion is by creating a Family Internet Safety Contract together so that everyone knows what is expected of them when they're online.

Other rules include public and timed use of the Internet, as stated on the It's Time We Talked website: "Young people's access to pornography is mostly via technology, so limiting exposure will require limiting and managing their access to technology. For example, by keeping devices out of bedrooms and other private spaces and putting time limits on use"(Reality & Risk Project, 2016).

Involvement in social media

The Office of the e-Safety Commissioner and Think U Know both discuss the benefits of social media, and parents/caregivers are advised of a number of ways to lend support to their children in their engagement in social media. For example:

- staying involved and supporting children to connect with friends and family online and in real life (IRL);

- checking terms of use and age guidelines of social networking sites;

- setting rules, such as that children inform parents that they are joining a new social network, and/or prior to sharing personal photographs or information;

- assisting children to create an online alias that does not indicate their gender, age or location; and

- establishing maximum security for children's social networking profiles (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016).

Further, parents/caregivers are advised to create accounts of their own on social networking sites as a way of staying involved in their children's social media activity and as a means of learning about social networking security. Think U Know also offers fact sheets for parents about popular social media such as Snapchat, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Tinder and Facebook.

Communication

Parents/caregivers' understanding and awareness of online pornography is central to how they communicate with their children about the associated risk of harm. The It's Time We Talked website contains information, advice and practical tools ranging from research about the pervasiveness of online pornography to advice about how to initiate discussions. Importantly, that resource emphasises the key role of parents/caregivers in communicating about the new reality of online pornography and promoting healthy development in children and young people (Reality & Risk Project, 2016).

The It's Time We Talked website, developed through the Reality & Risk Project, includes information specifically designed to educate young people about pornography. Another information hub, Think U Know, has developed a Cybersafety and Security guide to assist parents/caregivers in talking to their children about a range of online risks. The Office of the e-Safety Commissioner has compiled advice for parents/caregivers wishing to discuss online risks with their children. Similarly, It's Time We Talked offers tip sheets about how to have a conversation about online pornography and encourage critical thinking, as well as information for parents/caregivers about providing support and assisting their children in ongoing skill development. These are discussed in more detail below.

Advice and support

Parental support for children and young people who have been exposed to online pornography is extremely important to their ability to process their experience in healthy ways. Support is generally described as the ability of parents/caregivers to initiate open conversations about their experiences (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016). The e-Safety Commissioner offers advice about supporting children including:

- "encouraging them to talk to a trusted adult if they have seen something online that makes them upset, disturbed or distressed;

- reassuring them that access to the Internet will not be denied if they report seeing inappropriate content;

- telling them not to respond if they are sent something inappropriate."

- (Office of the Children's e-Safety Commissioner, 2016, "What can I do if my child sees content that's offensive?", para. 2)

Further, the Office of the e-Safety Commissioner advises parents/caregivers of the potentially devastating consequences of sexting for children and young people, and encourages them to discuss sexting as a family. Much of the advice provided on the website, however, discusses sexting in terms of the child's audience awareness and digital footprint. For example, it states that parents should:

- "encourage them to think twice before they post sexualised photos and consider the fact that others might view what they post;

- remind them to consider the feelings of others when taking photos and distributing any content by mobile phone or online." (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016, "Encouraging thinking first", para 1)

Digital footprint and context collapse

Rules about social media are largely conceptualised in terms of the digital footprint, and often referred to in terms of reputation management. For example, online resources offer the following information about social media and digital footprints:

- "Young people should be encouraged to stop and think before posting or sharing something online … Many employers, universities and sporting groups will search for applicants or potential members online before giving them a job or contract" (Think U Know, 2016, p. 22).

- "Encourage your kids to think before they put anything online, even among trusted friends, and remind them that once shared, information and photos can become difficult or impossible to remove and may have a long-term impact on their digital reputation" (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016, "Encouraging thinking first", para. 1).

In this way, these resources draw on the importance of audience awareness in the collapsed context of Internet spaces, particularly social media, which allow users a sense of symbolic control. Advising parents/caregivers to warn their children of context collapse and the digital footprint they create as a result of their online behaviour is a way of drawing attention to the wider problem of Internet security/privacy and the impact that the sharing culture may have on future activities and identities.

Ongoing skill development

The It's Time We Talked website offers practical advice for parents/caregivers to use in encouraging ongoing skill development in children and young people. In a section called Equip Them with Skills, it suggests "talking through the types of situations they might face and exploring the options for how they could respond" (Reality & Risk Project, 2016, "Equip them with skills, para 3). Additionally, it offers the following advice:

- Parents should talk through any challenges children face online, with regard to peer pressure, or web content that makes them feel uncomfortable, in a creative and collaborative way.

- Parents and children can develop strategies to address difficult situations, "for example, if they text you their name, you know to call them and ask them to come home, so they have an easy excuse to leave." (Reality & Risk Project, 2016, "Equip them with skills", para 3)

Further, the Office of the e-Safety Commissioner (2016) has developed Chatterbox for Parents, a "conversational how-to guide" informing parents/caregivers about "when to worry and when to celebrate the benefits the online world brings. Each conversation addresses the specific issues, behaviours and safety essentials to help you make sense of what's happening behind the screens (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016).

Teachers and schools

State and territory education departments have developed specific policies regarding cybersafety management in schools. The Office of the e-Safety Commissioner recommended individual schools set up an Online Safety Team to create and implement policies that promote cybersafety (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016). Schools are encouraged to consult widely with the school community, including teachers and support workers, students and parents/caregivers about online risks and harm minimisation (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016). Schools are also encouraged to draw on the national e-Smart Schools resource to assist in the creation of cybersafety policies and strategies.

Schools as a key setting

Quality sex education for children and young people has been identified as a protective factor in minimising the harms caused by exposure to online pornography (Pratt, 2015). The It's Time We Talked website observed that: "Schools increasingly are required to respond to incidents relating to explicit sexual imagery, including 'sexting' incidents, involving the circulation of sexual imagery of students" (IReality & Risk Project, 2016, "Why is porn an issue for schools?", para 1). Indeed, key resources for teachers and schools view schools as ideal settings to deal with the issue of young people's exposure to online pornography:

- "Many schools are already familiar with health promotion frameworks and are already engaged in related and complementary work, such as programs on respectful relationships, cybersafety, violence prevention, and sexuality education" (Reality & Risk Project, 2016, "Why schools?", para 4).

- "Schools can engage students about the influence of explicit sexual imagery as part of a comprehensive curriculum, with the input of highly skilled professionals and access to quality resources" (Reality & Risk Project, 2016, "Why schools?", para. 6).

- "Teachers and other staff in a school have a responsibility to take reasonable steps to protect students from risks of injury, including those that may be encountered within the online learning environment" (DET (Vic.), 2017, "Supervision", para. 1).

Schools are advised to:

- "arrange for policies and codes of conduct to be sent home for parental signature or sighting;

- establish a Cybersafety contact person or several people as a first point of contact for students, staff and parents if a cybersafety issue arises;

- review policies and procedures annually as technologies, and their use, evolves rapidly." (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016, "Policy development and implementation", paras 4-6)

Additionally, the High-Wire Act recommended that schools implement policy frameworks and set up Internet filters to meet the requirements of their state or territory governments (Cyber-Safety, J. S. C. o., 2011). It suggested that attentive supervision of students using computers at school worked well to provide additional support and protection (2011).

Sex education

There have been recent calls for more up-to-date and better quality sex education in schools. A recent national survey of 600 young Australian women found that "more than one third" of respondents wanted access to "more comprehensive education on sexuality and respectful relationships" (Plan International Australia & Our Watch, 2016, p. 3). Further, young women wanted such education to "extend to the critique and discussion of pornography … and how violent and degrading pornography was negatively impacting on young Australians' relationships and boys' and young men's attitudes towards sex in general" (Plan International Australia & Our Watch, 2016, p. 3).

Whole-of-school approach

The whole-of-school approach to deal with the effects of online pornography is a collaborative framework that promotes healthy sexualities in multiple contexts and not solely through sex education classes (Reality & Risk Project, 2016). All members of the school community, including parents/caregivers, teachers and students, are involved in such an approach, as stated in It's Time We Talked, the whole-of-school approach ensures that consistent messages are communicated at all levels of the school community (Reality & Risk Project, 2016). Schools have been named as key points of information about parental control of online risks and the associated harms of the Internet (Office of the e-Safety Commissioner, 2016; DET (Vic.), 2016).

The Catching On Everywhere (Department of Education and Early Childhood Development [DEECD] 2008) resource for the Victorian school curriculum advocates a whole-of-school, health-promotion approach to sex education that incorporates multiple contexts. It notes that a whole-of-school approach consists of "overlapping and interconnected domains: curriculum; teaching and learning; school organisation; ethos and environment; and community services and parent-partnerships" (DEECD, 2008, p. 12). Similarly, leading Australian sex educator Maree Crabbe calls for a whole-of-school and community-based approach to deal with the effects of online pornography on children and young people and has co-developed the In the Picture resource for that purpose (Reality & Risk Project, 2016).

Summary of approaches in Australia

At the primary prevention level, a key implication arising from the growing research and lessons learned is that treating the effects of pornography as a stand-alone issue disconnected from the broader contexts in which it is accessed, consumed and interpreted is unlikely to be effective in reducing its negative impacts/influence on children and young people. It is likely to be more effective to firstly hook the issue of online pornography into existing and tested curricula and approaches to:

- respectful relationships and quality sex education that is designed and delivered according to best practice principles; and

- media and digital literacy education.

These curricula can provide children and young people with a holistic framework and set of tools regarding:

- what makes for respectful relationships; how power, gender and equality are interlinked, and strategies for challenging and reimaging dominant narratives about (hetero) sex, gender difference, sexual pleasure and sexual relationships;

- mediated, mediatised representations, managing the context collapse between online and offline worlds, and the ability to critically engage with mass media representations.

Together these provide an important scaffolding to which strategies about online and cyber-safety can be added. It is also crucial is to build the capacity of parents and teachers to address gender, sex and porn with the children and young people in their care. Currently, this is an area of anxiety for many teachers and parents. There a number of resources available for parents in particular; however, as with children and young people themselves, having a broader scaffolding regarding gender, equality and sex is important.

Children and young people's exposure to online pornography has increasingly become an issue for governments and legislators around the world (Werrett, 2010; Valcke, De Wever, Van Keer, & Schellens 2011; Petley, 2014). Australia and comparable nations have established similar interventions across multiple contexts in order to meet the potential harms associated with children and young people's engagement with online pornography. The general aims of such interventions are to protect minors, promote the development of healthy sexual and digital literacies, and support greater congruence in the regulation of online and offline spaces - and the behaviours demonstrated therein (Chang, 2010; Laouris, Aristodemou, & Fountana, 2011; Jones, Thom, Davoren, & Barrie, 2013). This section will provide an overview of international interventions, focusing particularly on nations with comparable governments and social structures to Australia such as New Zealand, the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, the United States (USA) and Europe. The sections below discuss key examples of interventions related to law and governance, research, sex education and resources for parents/caregivers with regard to their children's risk of exposure to online pornography.

Law and governance

Legislation and guidelines work to delimit aspects of the Internet that can lead to children and young people's exposure to online pornography (Levin, 2010). While guidelines are not backed by legislative force, they provide Internet service providers, social networking sites and, in some cases, mobile network operators with self-regulatory frameworks and reporting protocols that enable standardised evaluation exercises (De Haan, Van der Hof, Bekkers, & Pijpers, 2013; Newman & Bach, 2004; Sarabdeen & De-Miguel-Molina, 2010). The inclusion of industry in government-led e-safety initiatives works to keep government abreast of developments and trends in digital technologies and involve stakeholders in important decision-making, and can increase industry commitment to safety strategies (De Haan et al., 2013; Newman & Bach, 2004). The implementation of government initiatives such as the family-friendly filter scheme in the UK, for example, would have been impossible without the working relationship between government and major Internet service providers (Leitch & Warren, 2015). This will be discussed in more detail below.

Table 6 shows important pieces of legislation and relevant guidelines that have been implemented to reduce children and young people's exposure to online pornography. In many cases, Internet filters are key to those regulations and have been implemented with varying effects. Recent legislation is yet to be evaluated, and indeed legislation from the UK has yet to be enacted. Human rights guidelines are included here due to their intended self-regulatory effect on social networking sites, mobile network operators and Internet service providers.

| Nation/Region | Intervention | Filtering | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand | Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015 Approved Agency under s 7 of the Act: Netsafe | No | Unavailable. Successful use in prosecutions related to cyberbullying and "revenge porn" (NZ Herald, 2016). |

| United Kingdom | Digital Economy Bill 2016 Approved Agency under Part 6 of Bill: Ofcom | Does not specifically legislate for filters but supports government partnerships that allow for their implementation. | Unavailable as Bill is yet to be enacted. Widespread criticism of the government filtering scheme rolled out in 2013 regarding human rights infringements that limit freedoms and searchable content related to diverse genders and sexualities, mental and sexual health and wellbeing (Leitch & Warren, 2015). |

| United States | Children's Internet Protection Act 2000 Purview: federally-funded schools and libraries | Yes | Successful implementation. Criticism that filters limit First Amendment rights to freedom of expression and searchable content related to diverse genders and sexualities, mental and sexual health and wellbeing (American Library Association [ALA], 2006; Rodden, 2003). |

| Canada | Provisions in nationwide criminal and civil law related to child pornography. Individual provinces have enacted their own laws with regard to "revenge porn" and cyberbullying (NoBullying, 2015) No specific laws regarding children and young people's exposure to explicit online content. | No | Some evaluation available in province-specific legislation, namely the Nova Scotia Cyberbullying Act. That Act was operational from 2013 to 2015 until it was declared defunct due to its infringement on charter rights of freedom of expression (Ruskin, 2015). |

| Europe | Human Rights Guidelines for Online Games Providers Human Rights Guidelines for Internet Service Providers Safer Social Networking Principles for the EU The European Framework for Safer Mobile Use by Younger Teenagers and Children | No | All guidelines are self-regulatory and not backed by legislative force. Some evaluation available. For example, it has been found that work is still needed for the Safer Social Networking Principles to be implemented effectively, particularly regarding "age-appropriate privacy settings and content classification" (De Haan et al., 2013, p. 120). |

New Zealand

While New Zealand does not have specific legislation regarding children and young people's exposure to explicit online material, the government of New Zealand introduced the Harmful Digital Communications Act in 2015 to address cyberbullying. Since its enactment it has been effectively used in prosecutions related to digital harassment and "revenge porn" (ref article). Part 1 of the Act states that it was developed "to establish and maintain relationships with domestic and foreign service providers, online content hosts and agencies" and "to provide education and advice on policies for online safety and conduct on the Internet" (Part 1, subpart 2, s 8). The Act also appointed an approved agency, Netsafe, to provide information and resources about e-safety in New Zealand (more will be said about that in later sections that address resources and social marketing (Netsafe, 2016)). Further, the Act has worked to formalise government-industry partnerships in order to ensure more effective regulation and industry compliance. The Harmful Digital Communications Act established partnerships between government and companies such as Google, Facebook and Twitter, allowing for the removal of harmful content from those websites by the government.

United Kingdom

The Digital Economy Bill 2016 was introduced into the House of Commons in July 2016 and is intended to regulate for, and enhance, digital activities, as well as "provide important protections for citizens from spam email and nuisance calls and protect children from online pornography" (Parliament of the UK, 2016). Part 3 of the Digital Economy Bill specifically deals with the matter of online pornography and issues of child protection. While other parts of the Bill treat issues such as intellectual property and access to digital services, Part 3 established a new law for commercial pornography websites that stipulates strict enforcement of age verification requirements. Additionally, government plans to engage with commercial pornography industries, age verification providers and payment providers such as Visa and PayPal are pitched to promote greater industry compliance in restricting online pornography consumption among minors.

The government concern for children and young people's access to online pornography also drove the government-led Internet filtering scheme, which was implemented across the UK through major Internet service providers in 2013 (Leitch & Warren, 2015). That scheme was part of a government-industry partnership whereby four major providers delivered automatic pornography filters through their Internet connection with the intention of restricting access to explicit online content among minors (Leitch & Warren, 2015). While the scheme contained an "opt out" caveat for adults, the filter was condemned as an infringement on rights to freedom of expression, namely as it blocked broadly defined sexual content, including information about sexualities, sexual health and wellbeing, and LGBTQI communities (Leitch & Warren, 2015).

United States

The USA implemented the Children's Internet Protection Act 2000 in order to mediate children and young people's engagement with explicit online material. The Act introduced strict filtering policies that required federally-funded schools and libraries to block online material inappropriate to children and young people under 17 years of age (Haynes, Chaltain, Ferguson, Hudson, & Thomas, 2003). The Act is widely criticised for infringing on rights of freedom of expression, particularly with regard to blocking information about sexualities, sexual health and wellbeing, and LGBTQI communities (ALA, 2006; Haynes et al., 2003).

Canada

As mentioned above, no specific laws regarding children and young people's exposure to explicit online content exist in Canada and there is no nationwide legislation for children and young people's general e-safety. However, non-government agencies in addition to province-specific governments have developed their own laws and guidelines to promote healthy digital habits. For example, Project Cleanfeed was established by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection in 2007 to block websites hosting child pornography (Cybertip, 2016). Further, the Nova Scotia Cyberbullying Act works as an example of an unsuccessful legal intervention, whereby cyberbullying laws were found to infringe on rights of freedom of expression (Ruskin, 2015).

Europe

Individual European nations have developed their own legislation with regard to e-safety issues and digital activities. However, guidelines for Europe as a global region have been adopted by many nations therein, and mostly contain self-regulatory principles to guide industry practice (Council of Europe, 2008; European Commission, 2009). De Haan et al. (2013, p. 111) observe that governments may prefer self-regulatory tactics for digital industries, noting that:

Public officials often assume that industry practitioners have more expertise and technical knowledge. Utilisation of this knowledge and expertise leads, one assumes, to greater compliance and effectiveness since practical rules can be more easily developed, and also greater efficiency because of lower costs of gathering information for the state.

Most major social networking sites in Europe implemented the Safer Social Networking Principles in 2009 as a mechanism for self-regulation. A 2013 evaluation of that initiative stressed that the principles "must be seen in light of an ongoing dialogue on online child safety and the respective roles of other stakeholders, like parents, government, police, civil society and SNS users themselves" (De Haan et al., 2013, p. 118). As mentioned above, implementation was evaluated as ineffective with regard to age-appropriate content and safety for children and young people.

An evaluation of the Framework for Safer Mobile Use also stressed the importance of multi-stakeholder involvement to successfully address e-safety issues. The European Commission found that implementation of the framework was effective; however, further recommendations for the framework included the classification of commercial materials to ensure age-appropriate content for minors and parental controls to block online content on their children's devices (De Haan et al., 2013).

Sex education

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA; 2016, "Comprehensive Sexuality Education - Overview", para 2) states that:

Comprehensive sexuality education enables young people to protect their health, wellbeing and dignity. And because these programs are based on human rights principles, they advance gender equality and the rights and empowerment of young people.

Further, comprehensive sexuality education, as expressed in the United Nations definition, should provide age-appropriate information that incorporates understandings of children's and adolescents' stages of development, and engage parents/caregivers and the wider community to reinforce healthy sexual development in multiple contexts (UNFPA, 2016). While many European countries deliver sex education in a manner consistent with the United Nations description, many states in the USA continue to resist delivering such programs. Table 7 demonstrates differences between sex education governance, underlying frameworks and outcomes in the USA, the Netherlands and Sweden - with the latter two often used as best-practice models for sex education. Table 7 describes aspects of that education including the ways in which government mandates for sex education, the dominant framework underpinning the programs and available evaluations of that education.

| Nation | Government requirements | Dominant framework | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | US Congress provides funding for sexual health programs and, in 2015, also increased its funding for abstinence-only education for young people (De Melker, 2015). Less than 50% of US states regulate for compulsory sex education to be delivered in schools (Jones & Cox, 2015). 24 states and the District of Columbia require schools to deliver sex education, of which 22 states and the District of Columbia require combined HIV education and sex education programs (Guttmacher Institute, 2016). | Moral/religious frameworks underpin dominant models of sex education with an emphasis on abstinence and risk avoidance (pregnancy, disease) in heterosexual intercourse (Bell, 2009; De Melker, 2015). | 37% of young people say their sex education classes were unhelpful, and 75% favour more comprehensive sex education programs (Jones & Cox, 2015). Young people experience first sex at a younger age than their Dutch counterparts, and often regret that experience (Albert, 2004; De Melker, 2015). The teen pregnancy rate is five times higher for young people in the US than that in the Netherlands, which has been noted as a symbol of unsuccessful interventions (De Melker, 2015). |

| The Netherlands | Mandatory sex education required for all students beginning in preschool and teachers required to learn about sex education programs as part of their qualification (European Union, 2013; The SAFE Project, 2006). | Gender equity and sexual ethics frameworks underpin dominant models of sex education. Critical skills and personal empowerment are included in the program. Frameworks support open discussions about love, sexuality, gender, health, boundaries and pleasure (The SAFE Project, 2006). | Found to reflect public health models of rights, responsibility and respect as foundations of sexual health (De Melker, 2015). Dutch young people have excellent sexual health outcomes compared to the USA and other developed nations (Currie et al., 2012). |

| Sweden | Mandatory sex education required for all students beginning in preschool and teachers required to learn about sex education programs as part of their qualification (European Union, 2013; The SAFE Project, 2006). | Gender equity and sexual ethics frameworks underpin dominant models of sex education. Respectful relationship education is a key component of the program. Critical skills and personal empowerment are included in the program. Frameworks support open discussions about sexuality, gender, health, boundaries, and pleasure ( De Melker, 2015: The SAFE Project, 2006) 2015) | Found to support a liberal approach that encourages responsibility and respect (De Melker, 2015). Sex education in schools is supported by social marketing and youth friendly sexual health services (Bell, 2009). |

Resources

Free online sources have been developed around the world in a similar fashion to Australia, providing information about e-safety and online pornography that is specifically tailored to parents/caregivers, teachers, children and young people. Table 8 highlights key resources from New Zealand, the UK and Europe, and discusses key aspects of the material they provide and evaluations of them.

| Nation | Resource | Key aspects | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand | Netsafe | Information for parents/caregivers about how to manage their children's exposure to online pornography.

Ineffective mediation:

Online reporting mechanism available. | Unavailable. Underpinned by child-centred principles whereby children are encouraged to make sense of their experiences in healthy ways. Recommended by government agencies, Netsafe is the approved agency under the Harmful Digital Communications Act. |

| UK | National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) | Harm minimisation tactics recommended for parents/caregivers:

Online reporting mechanism. | Unavailable. Underpinned by child protection principles whereby safeguarding children from online pornography is a government responsibility as well as the duty of parent/caregivers. |

| Canada | Media Smarts | Describes itself as a Centre for Digital and Media Literacy. Effective mediation:

Ineffective mediation:

| Unavailable. Uses principles associated with child protection as well as child-centred models. For example, children are taught critical thinking skills to apply in their independent experiences but parents/caregivers are still advised to exercise parental controls to safeguard their children's digital activities. |

We reviewed what the available research evidence suggests about the impact that exposure to and consumption of online pornography has on children and young people in terms of children and young people's:

- knowledge of and attitudes to sex;

- sexual behaviours and practices;

- attitudes and behaviours regarding gender equality;

- behaviours and practices within their own intimate, sexual or romantic relationships; and

- risk of experiencing or perpetrating sexual violence.

The table below sets out the scope and strategy for undertaking the evidence scan.

| Element | Areas of focus | Search strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Pornography and other social/cultural practices that lead to sexualisation of children, and its effects on children and young people |

|

|

| Current approaches and interventions to address the negative effects of pornography |