Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms: Summary report

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2009

Rae Kaspiew, Kelly Hand, Lixia Qu

Download Research report

Summary report contents

- 1 Background

- 2 Evaluation methodology

- 3 Evaluation findings

- 3.1 Characteristics of separated parents: Challenges and issues for family relationships and wellbeing

- 3.2 Use and effectiveness of new and expanded family relationship service

- 3.3 Pathways towards parenting arrangements

- 3.4 Family dispute resolution

- 3.5 Care-time arrangements: Community opinions, prevalence and durability of different arrangements, and trends across the years

- 3.6 Care-time arrangements: Negotiations and family profiles

- 3.7 Parental responsibility: Decision-making about issues affecting the child and financial support

- 3.8 Parental responsibility and time: Perspectives and practices of lawyers and other service providers

- 3.9 Family violence and child abuse: Parents' pathways and professionals' perspectives

- 3.10 Children's wellbeing

- 3.11 Grandparenting and the family law reforms

- 3.12 The 2006 reforms and the courts

- 3.13 The implementation of Division 12A of Part VII: Principles for conducting child-related proceedings

- 3.14 The application of the SPR Act 2006 amendments to the Family Law Act 1975

- 4 Implications of the findings for the key evaluation questions

- 5 Conclusion

- References

- Endnotes

1 Background

In 2006, the Australian Government introduced a series of changes to the family law system. These included changes to the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) 1 and increased funding for new and expanded family relationships services, including the establishment of 65 Family Relationship Centres (FRCs) and a national advice line. The aim of the reforms was to bring about "generational change in family law" and a "cultural shift" in the management of separation, "away from litigation and towards co-operative parenting".2

The 2006 reforms were partly shaped by the recognition that although the focus must always be on the best interests of the child, many of the disputes over children following separation are driven by relationship problems rather than legal ones. These disputes are often better suited to community-based interventions that focus on how unresolved relationship issues impact on children and assist in reaching parenting agreements that meet the needs of children.

The changes to the family law system followed an inquiry by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Constitutional Affairs (2003), which recommended changes to the family relationship services system and the legislation.3 The committee's report, Every Picture Tells a Story, made recommendations that aimed to make the family law system "fairer and better for children". The 2006 changes reflected some, but not all, of the recommended changes.

In 2006, the Australian Government, through the Attorney-General's Department (AGD) and the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), commissioned the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) to undertake an evaluation of the impact of the 2006 changes, reflecting the need for future decision-making to proceed on the basis of rigorously collected and analysed data. The evaluation assesses the extent to which, by 2009, the changes to the family law system had been effective in achieving the policy aims set for them.4

The evaluation has involved the collection of data from some 28,000 people involved in the family law system, including parents, grandparents, family relationship services staff, clients of family relationship services, lawyers, court professionals and judicial officers and the analysis of administrative data and court files.

This evaluation provides a more extensive evidence base about the use and operation of the family law system than has previously been available in Australia and is arguably more extensive than other studies that exist internationally.

This summary report provides an overview of the evaluation findings. The evaluation is of the changes to the system three years after commencement of the "roll-out" of the reforms.5

1.1 The 2006 changes to the family law system

The policy objectives of the 2006 changes to the family law system were to:

- help to build strong healthy relationships and prevent separation;

- encourage greater involvement by both parents in their children's lives after separation, and also protect children from violence and abuse;

- help separated parents agree on what is best for their children (rather than litigating), through the provision of useful information and advice, and effective dispute resolution services; and

- establish a highly visible entry point that operates as a doorway to other services and helps families to access these other services.6

The changes to the family law system included changes to both the legislation and the family relationship services system. The legislative changes comprised four main elements, which:

- require parents to attend family dispute resolution (FDR) before filing a court application, except in certain circumstances, including where there are concerns about family violence and child abuse (SPR Act 2006 s60(I));

- place increased emphasis on the need for both parents to be involved in their children's lives after separation, through a range of provisions, including the introduction of a presumption in favour of equal shared parental responsibility (SPR Act 2006 s61DA; see also s60B(1)(a), s60CC(2)(a));

- place greater emphasis on the need to protect children from exposure to family violence and child abuse (SPR Act 2006 s60B(1)(b), s60CC(2)(b)); and

- introduce legislative support for less adversarial court processes in children's matters (SPR Act 2006 Division 12A of Part VII).

The changes to the family relationship services system included the establishment of 65 FRCs throughout Australia (designed to provide a gateway to the system for families needing assistance), funding for new services, and additional funding for existing services.7 The FRCs aim to provide assistance for families at all relationship stages, and offer impartial referrals, advice and information aimed at helping families to strengthen their relationships and deal with relationship difficulties. They also provide family dispute resolution (FDR) to separating families to assist with the development of parenting arrangements. The first fifteen FRCs commenced operation from July 2006 and 64 were operational by July 2008. The final centre opened in October 2008.

In addition to FRCs, a range of other services provided as part of the Family Relationship Services Program (FRSP). The other FRSP services were included in the evaluation:

- Family Relationship Advice Line (FRAL) and the associated Telephone Dispute Resolution Service (TDRS);

- Family Relationships Online (FRO);

- family dispute resolution and regional FDR services;

- Children's Contact Services (CCS);

- Parenting Orders Program (POP);

- family relationship counselling services;

- Mensline Australia;

- Men and Family Relationships Services (MFRS);

- Specialised Family Violence Services (SFVS); and

- Family Relationship Education and Skills Training (EDST).

1.2 Key evaluation questions

The policy objectives outlined above encompassed a range of more specific goals. A set of indicators of the success or otherwise of the reforms in achieving these objectives was developed. These have been translated into a series of evaluation questions:8

- To what extent are the new and expanded relationship services meeting the needs of families?

- What help-seeking patterns are apparent among families seeking relationship support?

- How effective are the services in meeting the needs of their clients, from the perspective of staff and clients?

- To what extent does FDR assist parents to manage disputes over parenting arrangements?

- How are parents exercising parental responsibility, including complying with obligations of financial support?

- What arrangements are being made for children in separated families to spend time with each parent? Is there any evidence of change in this regard?

- What arrangements are being made for children in separated families to spend time with grandparents? Is there any evidence of change in this regard?

- To what extent are issues relating to family violence and child abuse taken into account in making arrangements regarding parenting responsibility and care time?

- To what extent are children's needs and interests being taken into account when these parenting arrangements are being made?

- How are the reforms introduced by the SPR Act 2006 working in practice?

- Have the reforms had any unintended consequences - positive or negative?

2 Evaluation methodology

The evaluation is based on an extensive range of studies that examine the views and experiences of parents, grandparents, family relationship service professionals and professionals from the legal and court sector. Court data and government program (administrative) data have also been used. Some of the evaluation data provide information about the operation of the family law system prior to the 2006 changes and thus provide benchmark (also termed "baseline") information against which change can be measured. The evaluation uses qualitative and quantitative methods and legal analysis. It is strengthened by the fact that the key findings are based upon data collected from multiple sources, using different methods. This provides "triangulation" for the key findings.

In order to address the evaluation questions, information was obtained from three major studies:

- the Legislation and Courts Project, which examined the implementation of the SPR Act 2006 (Cth) through a series of interviews and focus groups with family law system professionals, a survey of family lawyers, an analysis of family court files and an analysis of case law;

- the Service Provision Project, which looked at the effectiveness of changes to the service sector, including the introduction of FRCs, through interviews and focus groups with family relationship service professionals, and surveys of FRSP staff and FRSP clients; and

- the Families Project, which focused on the experiences of parents in general, parents who separated before and after the 2006 changes and grandparents with a grandchild whose parents had separated.

Information was collected from:

- parents who had separated prior to the 2006 reforms (baseline or pre-reform data) - 2,005 parents;

- parents who separated after the 2006 reforms - 10,002 parents;

- nationally representative surveys (pre-reform and post-reform) of all parents (including separated parents) - 5,000 parents in each survey;

- grandparents who had an adult child who had separated - 562 grandparents;

- clients of services funded as part of the family law system - 3,251 clients;

- relationship service providers, including managers and staff employed in different types of relationship services - 1,668 service providers;

- survey of family lawyers (pre- and post-reform) - 319 lawyers pre-reform and 367 lawyers post-reform;

- qualitative interviews with judicial officers, registrars, lawyers and family consultants - 184 legal professionals;

- program data related to government-funded family relationship services;

- published judgments; and

- court files from the Family Court of Australia (FCoA), Federal Magistrates Court (FMC) and Family Court of Western Australia (FCoWA) (pre- and post reform) - 985 pre-reform and 739 post-reform, a total of 1,724 court files.9

Figure 1 provides an overview of the data collected during the course of the evaluation.

Figure 1 Data collected in the course of the evaluation

The following section summarises the findings of each chapter in the full evaluation report. The final section in this summary report draws together the implications of these findings for the key evaluation questions.

3 Evaluation findings

3.1 Characteristics of separated parents: Challenges and issues for family relationships and wellbeing

In order to evaluate the changes to the family law system, it is important to have a clear picture of the characteristics of families using the family law system, the prevalence of family violence, mental health problems and issues relating to drug and alcohol misuse and other addictions, and the quality of inter-parental relationships.

While the family law system deals with families from all sectors of society, separated parents have, on average, a lower level of education and are more likely to have a preschool-aged child when they separate than parents who stay together.

3.1 1 Family violence10 and safety concerns

Around two-thirds of separated mothers and just over half of separated fathers indicated that their child's other parent had emotionally abused them before or during the separation. One in four mothers and around one in six fathers said that the other parent had hurt them physically prior to separation and, among those who reported such experiences, most indicated that their children had seen or heard some of the abuse or violence.11 When family court files (FCoA, FMC and FCoWA) were examined, over half of the files contained an allegation of family violence on the written file.

Around one in five parents reported that they held safety concerns associated with ongoing contact with their child's other parent and over 90% of these parents had been either physically hurt or emotionally abused by the other parent.

3.1.2 Mental health and misuse of alcohol or other drugs

Half the mothers and around one-third of the fathers said that mental health problems and/or misuse of alcohol, other drugs or other addictions were issues in their family before separation.

3.1.3 Nature of the post-separation inter-parental relationship

While many separated families had to deal with complex issues, it is also important not to lose sight of the fact that a majority of separated mothers (62%) and fathers (64%) had friendly or cooperative relationships with each other about 15 months after separation. About a fifth had a distant relationship and a little under a fifth had a highly conflicted or fearful relationship.

3.2 Use and effectiveness of new and expanded family relationship services

There was an increase in the number of clients for all FRSP service types over the period 2006-07 to 2008-09. The number of:

- FRC clients increased from about 14,000 to 60,000;

- FDR clients increased from about 14,500 to 22,500;

- CCS clients increased from about 11,000 to 23,500;

- POP clients increased from about 3,000 to 8,000;

- SFVS clients increased from about 3,500 to 7,000;

- MFRS clients increased from about 24,000 to 28,000;

- counselling services clients increased from about 63,500 to 101,000; and

- EDST clients increased from about 32,000 to 49,500.

3.2.1 Early intervention services

The additional funding provided to early intervention services (EIS)as part of the 2006 changes was designed to prevent separation and help families build strong healthy relationships. Only a minority of partnered parents who had not experienced problems in their relationship had used relationship services to assist them in supporting their inter-parental relationship (about one in ten). However, among partnered parents who had thought that their relationship had been in serious trouble at some stage, half had used relationship or other services to attempt to address their relationship problems. Parents who used these services, along with other EIS clients, had high levels of satisfaction with the service they attended.

3.2.2 Post-separation services

About two-thirds of parents who separated after the 2006 changes had used family relationship services after separating. These parents were less likely than those who separated prior to the 2006 changes to have used lawyers or court process (data from Wave 1 of the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families [LSSF W1] 2008 and the Looking Back Survey [LBS] 2009). However, there was an increase post-reform in the proportion of separated and non-separated parents who thought that it was important to consult a lawyer if thinking of separating (data from the General Population of Parents Surveys [GPPS] 2006 and 2009).

Services are predominantly being used by parents who had significant relationship issues. For instance, separated parents who used family relationship services were much more likely to have experienced family violence, mental health problems or drug and alcohol misuse issues than separated parents who did not use services. Separated parents who used services were also more likely to have a distant, conflictual or fearful relationship with their child's other parent.

Family dispute resolution services also mainly deal with cases that involve high levels of complexity and high levels of conflict. A significant minority of cases referred to FDR involved serious family violence or the risk of abuse to the child and were judged by these service providers to be inappropriate for FDR and to qualify for an exception from FDR under s60I(9) of the SPR Act 2006.

Compared with EIS clients, post-separation service (PSS) clients rated the services they attended less favourably on a number of dimensions, although FRCs and FDR services were rated favourably by the majority of clients.

Of the issues examined, clients of FRCs and FDR mostly provided positive assessments of their service's provision of assistance in negotiating with the other parent post-separation. On the other hand, compared with clients of other face-to-face FRSP services, clients of FRCs and FDR services were less inclined to rate positively the ability of these services to provide them with the help they needed. This is not surprising given the complexity of issues contributing to relationship breakdown.

Service professionals rated the capacity of their organisations to deliver relevant services as being generally high and overall they were confident about their capacity to work with different family types. However, language and cultural barriers were seen to be a problem by a considerable number of staff. This is likely to reflect the reality that many services are simply unable to cover the range of languages in their locations except through the use of interpreter services.

On balance, the evidence is that of fewer post-separation disputes being responded to primarily via the use of legal services and more being responded to primarily via the use of family relationship services. This suggests a cultural shift whereby a greater proportion of post-separation disputes over children are being seen and responded to primarily in relationship terms.

3.3 Pathways towards parenting arrangements

Nearly three-quarters of parents who separated after the 2006 changes had sorted parenting matters out within a year or so of separating. A substantial minority of these parents made little or no use of services such as counselling, FDR, lawyers or courts. On average, those who used services used 1.8 different types of services. Fewer than a fifth of parents said that they were "still sorting things out", and for only 10%, "nothing was sorted out".

The main means of resolving parenting issues were discussions with the other parent, followed by a sense that the arrangements "just happened". This was true both for parents who separated prior to the 2006 changes and those who separated after the 2006 changes. Most parents who had reached agreements, or were in the process of reaching agreements via discussions between themselves, felt the process worked for them, for their former partners and for their children. Parents separating pre-reform were considerably more likely to have used lawyers and courts to help them resolve matters or make decisions than parents who separated after the reforms.

Many separated parents did not contest parenting arrangements to any significant extent. Most parents were finding informal ways of negotiating arrangements for their children and were generally satisfied with the negotiation processes.

An important finding is that half of the parents separating after July 2006 who had sorted out their parenting arrangements also reported having experienced family violence (with about twice as many reporting experiencing emotional abuse alone as those experiencing physical hurt). About three-quarters of parents who were still sorting out their parenting arrangements or for whom nothing had been sorted out had experienced violence. A third of these parents reported having been physically hurt and a little over two-fifths reported emotional abuse alone.

Among both the pre-reform and post-reform samples of separated parents who sought assistance, those who used FDR services were the most satisfied with the processes they experienced, while those who went to court were the least satisfied. Generally, parents who sought help from lawyers reported satisfaction levels that were in between these two. These patterns of client ratings are likely to reflect the fact that most cases that reach the courts, and to a lesser extent lawyers, involve very difficult issues.

FRSP staff generally felt that they had enough information about the family law reforms to enable them to assist clients, although EIS staff were the least confident in this regard. These same service providers generally confident about their own referral processes and protocols and frequently, although by no means universally, rated positively their capacity to work with other FRSP-funded services and a wide range of other services. At the same time, they believed that a considerable number of their clients were unclear about the requirements to attend FDR.

FRAL staff were less positive about their service's capacity to work with other FRSP-funded services and referral pathways than staff working in other types of services.12 It may be that the relative isolation of such a telephone service and the comparatively brief nature of many of the calls generate a range of uncertainties about the real nature of the services "out there".

The gateway function of the Family Relationship Centres is yet to become fully established. Only about half of the other service providers and only about a third of practising lawyers saw the FRCs as being an integral part the family law system. However, although many family lawyers expressed a reluctance to refer clients to services generally, many of those who made such referrals were more comfortable in referring to FRCs than to other services.

3.4 Family dispute resolution

FDR appears to work well for many parents and their children. Among parents who had separated after the reforms, 31% of fathers and 26% of mothers reported that they had "attempted family dispute resolution or mediation". About two-fifths of this group reached an agreement and most of these agreements were still in place at the time the LSSF W1 2008 was conducted (about a year after separation). Most parents who had not reached agreement at FDR had sorted out their dispute at the time the survey was conducted. Whether or not FDR resulted directly in an agreement, the majority of parents who had attended FDR and who had sorted out their disputes felt that they had done so mainly through discussions between themselves. This is consistent with a key aim of FDR, which is to empower disputants to take charge of their dispute. Parents who had not reached agreement at the time of FDR and who were issued with a certificate (affording them "entry" into the court system) were the least likely to have sorted matters out or to have had a decision made about their dispute.

Most disputes referred to FRCs appear to be complex. Indeed, FRCs have become an early point of entry for a significant number of parents whose capacity to mediate is compromised to a greater or lesser extent by their past or present experience of violence, fear or dysfunctional behaviour. FRCs are regarded by a proportion of lawyers as the most logical entry point for effective triage and effective referral of complex cases. There is also evidence that referral of difficult cases, either to FRCs or to an FDR service, is sometimes regarded as an insurance policy. Thus, although some of the cases clearly meet the criteria for an exception under s60I(9), lawyers are not always confident that courts will see the situation this way. Such cases are frequently issued with certificates by FDR practitioners. At the same time, some parents who would probably meet the exception criteria, commence and/or complete FDR.

There are no easily predictable "best" pathways for this problematic end of the dispute resolution spectrum. Some clients reported that they felt pressured into FDR or into reaching an agreement. Others with seemingly similar complex family dynamics did not provide this feedback. The new skills-based training for accrediting FDR practitioners is designed to increase capabilities in this area.

The data indicate considerable overlap between client use of lawyers and client use of FDR. Clearly, the advocacy role that lawyers must play on behalf of their clients is capable of complementing or colliding with the work of an FDR practitioner. Therefore, any initiatives that promote a shared commitment to responsible FDR between lawyers and FDR professionals, and between lawyers and the service sector, is likely to improve the efficacy of FDR. FDR professionals and other service sector staff need to be actively engaged with each other if they are to avoid re-creating between themselves their own clients' high conflict and low trust.

On the one hand, the data suggest continuing concerns by lawyers about FDR and the service sector in general. On the other hand, there were also many instances, most especially from regional centres, of lawyers, FDR professionals and other service professionals working cooperatively towards achieving post-separation arrangements between ex-partners that were likely to assist children to flourish.

3.5 Care-time arrangements: Community opinions, prevalence and durability of different arrangements, and trends across the years

A key objective of the 2006 family law reforms was to encourage greater involvement of both separated parents in their children's lives after separation, provided that the children are protected from family violence or child abuse. "Involvement" entails such matters as: (a) taking primary care of the children, including overnight where possible; (b) contributing to decisions affecting children's general lifestyle and welfare; and (c) providing financial support. The concept of "parental involvement" thus overlaps with the exercise of "parental responsibility", although involvement may be understood as "what happens", whereas "responsibility" conveys notions of accountability or obligation.

This section describes the time that parents spend with their children post-separation, Section 3.6 focuses on how care-time arrangements are negotiated and the characteristics of families with different care-time arrangements, and Section 3.7 focuses on parents' involvement in decision-making and financial support.

In the evaluation, the term "shared care time" is used to refer to the situation in which a child spends 35-65% of nights with each parent (cut-offs that are consistent with those in the Child Support Scheme) and "equal care time" as the situation in which a child spends 48-52% of nights with each parent.

Most parents with a child under 18 years old agreed that the continuing involvement of each parent following parental separation is beneficial for the children (81% of parents interviewed in 2009). In 2006, the proportion of parents believing that the continuing involvement of each parent following parental separation is beneficial for the children was slightly lower (77%).13 While this may reflect a small cultural shift in views towards an increased conviction about the importance of continuing parental involvement, further monitoring is required to assess whether the trends continue to hold or whether they reflect a fluctuating pattern of views. In addition, most parents in the 2009 survey believed that spending approximately half the time with each parent can be appropriate, even for children under 3 years old.

The proportion of children with separated parents who experienced shared care-time arrangements increased after the July 2006 changes were introduced, as evidenced by comparisons of data collected from surveys of separated parents, the CSA and court files. The court file data suggest that the increase is especially marked among families whose dispute was finalised through judicial determination.

However, the increasing prevalence of shared care-time arrangements began well before the reforms were introduced and appears to be part of an international trend. Future monitoring of trends will indicate whether the increase in shared care-time arrangements gained further momentum after the 2006 changes were fully rolled out.

Although the overall incidence of shared care time has increased, such an arrangement is experienced by only a minority of children. According to data from the LSSF W1 2008, 16% of children whose parents separated between July 2006 and September 2008 (and were registered with the CSA in 2007) had a shared care-time arrangement, with the proportion varying considerably according to the age of the child.14 Specifically, such arrangements were experienced by:

- 8% of children under 3 years old;

- 20% of children aged 3-4 years;

- 26% of children aged 5-11 years;

- 20% of children aged 12-14 years; and

- 11% of children aged 15-17 years.

Most children spent most or all nights with their mother, with one-third spending all nights with their mother. Of the children who never stayed overnight with their father, two-thirds saw their father during the day and the other third did not see him at all.

Data from the LBS 2009, which focused on parents who separated between January 2004 and June 2005, suggest that, over an interval of some 4 to 5 years after parental separation, the most durable care-time arrangement was the traditional one (where the children lived mostly or entirely with their mother). The second most durable arrangement was equal care time. A similar level of durability was apparent for shared care time involving more nights (53-65% of nights) with the mother than father and circumstances in which the child spent 66-100% of nights with the father.

In short, traditional care-time arrangements, involving more nights with the mother than father, remained the most common and appear to be the most stable arrangement over a 4- to 5-year interval. However, shared care time is increasing both among separated families in general and among those whose dispute was litigated, especially among families whose dispute was finalised through judicial determination.

3.6 Care-time arrangements: Negotiations and family profiles

Families in the LSSF W1 2008 with different care-time arrangements varied considerably across a range of circumstances. For example, there was a close link between post-separation care-time arrangements and respondents' reports about the other parent's level of involvement in the child's everyday activities prior to separation. The greater the level of pre-separation involvement, the greater, on average, the amount of care time post-separation.

Families in which the father did not have the focus child stay overnight can be divided into those who had daytime-only care and those who never saw the child. The mothers and fathers with these arrangements tended to be relatively young and were the least likely of all groups to have been living with the child's other parent at the time the child was born. While there were clear socio-demographic similarities between these two groups, the distance between the two homes, the sorting out of parenting arrangements and family dynamics were quite different.

Firstly, fathers who never saw their child were less likely than those with daytime-only care to live within 20 km or a 30-minute drive from the child's mother (with around one-third of the former group living at least 500 km or a 6-hour drive from her). These fathers were also more likely than those with daytime-only care to have re-partnered.

Secondly, parents whose child never saw his or her father were less likely than those whose child experienced daytime-only care with the father to indicate that their parenting arrangements had been sorted out, and where arrangements had been sorted out, those whose child never saw the father were less likely to indicate that this had been achieved mainly through discussions with the other parent. They were more likely to report that the arrangements had "just happened".

Thirdly, regarding family dynamics, parents whose child never saw the father reported less frequent communication with the other parent, were more likely to describe the inter-parental relationship as highly conflictual or fearful, and were less likely to view it as friendly or cooperative. Consistent with this, both the fathers and mothers in these families were more likely than those in families in which the child saw the father during the daytime only to report that they had been physically hurt by the other parent. The former group of fathers were also more likely than the fathers with daytime-only care to indicate that they had experienced emotional abuse alone.

Concerns about their personal safety or the safety of their child relating to contact issues were more likely to be expressed by mothers and fathers whose child never saw the father, than by those whose child saw the father during the daytime only. Parents (especially mothers) of children who never saw their father, were also more likely than parents of children who saw the father during the daytime only to indicate that before separation there had been mental health problems, concerns about the misuse of alcohol and other drugs, and concerns about addictions such as gambling.

Overall, families in which the father had daytime-only care seemed similar, in terms of these family functioning issues, to those in which the father cared for the child for a minority of nights (1-34% of nights). Those in which the child never saw the father tended to have more problematic family functioning issues than most other groups.

Parents with shared care-time arrangements were as likely or more likely than parents with other care-time arrangements to believe that their parenting arrangements were working well for the child, mother and father (reported by 70-80% of parents with a shared care-time arrangement who provided assessments for all three parties). While most parents with shared care-time arrangements reported friendly or cooperative relationships, they were more inclined to report problematic family dynamics than parents in families in which the father had fewer overnight stays or daytime-only care (especially the latter group). For example, compared with families in which the father had daytime-only care, both mothers and fathers with shared care-time arrangements were more likely to report having experienced some form of family violence prior to separation.

For the most part, pre-separation experiences of violence and perceived issues relating to mental health, the misuse of alcohol and other drugs or specified addictive behaviours, along with current safety concerns associated with ongoing contact with the other parent, were more commonly reported by parents whose child never saw the father or had limited or no time with the mother than by other groups of parents. Although this is consistent with the aim of the family law system to protect children's wellbeing, the other side of the coin is that there is a significant minority of children in shared care-time arrangements who have a family history entailing violence and a parent concerned about the child's safety, and who are exposed to dysfunctional behaviours and inter-parental relationships.

3.7 Parental responsibility: Decision-making about issues affecting the child and financial support

Analysing the extent of shared parental responsibility is central to evaluating the extent to which the policy objective of encouraging greater involvement of both parents in children's lives after separation has been achieved. The evaluation collected information from parents (as part of the LSSF W1 2008) about the sharing or otherwise of decision-making about key issues that have an impact upon the long-term development and wellbeing and financial support of children.15

3.7.1 Shared decision-making

Shared decision-making is much more likely where there is shared care time than where the child spends most or all nights with one parent. For example, 79% of fathers with equal care time (48-52% of nights) said that education decisions were shared by the parents, compared to 32% of fathers who had daytime-only contact with their child.

The sharing of decision-making was also closely linked to the extent to which the father was involved in the child's day-to-day activities before separation, with higher levels of pre-separation involvement being associated with a greater tendency to report the sharing of child-related decisions post-separation.

While shared decision-making represents an important means by which both separated parents can remain involved in their children's lives, its advantages are undermined where there are risks of family violence. Shared decision-making is less commonly reported by respondents who said that their child's other parent had emotionally abused them or physically hurt them (especially the latter) or who had ongoing safety concerns about contact with the other parent. Nonetheless, a substantial proportion of parents who reported a history of family violence or ongoing safety concerns indicated that decision-making was shared. For example, 37% of mothers who held safety concerns reported that education decisions were jointly made.

While decision-making practices reported by parents varied considerably, legal orders concerning parental responsibility demonstrate a strong trend, pre-dating the reforms, for legal decision-making power to be allocated to both parents. There is no evidence of significant changes in the extent to which orders for shared parental responsibility are made. Orders made by judicial determination are more likely to allocate decision-making power to one or other parent (more often the mother) than those made by consent. Cases in which decision-making is removed from one parent commonly involve concerns about family violence and child abuse.

3.7.2 Financial support post-separation

Ongoing financial support for children after parental separation is another key aspect of parental involvement. More than half of parents with a child support liability reported that the liability was fully complied with (in terms of amount and time), with payers (especially fathers) being more likely than payees to indicate full compliance. Father payers and mother payees whose child lived mostly with the mother were more likely to report paying or receiving child support than those with shared care-time arrangements and those whose child was mainly with the father. However, there was no apparent link between child support payment compliance and care-time arrangements.

Non-compliance in terms of payment amount or its timing seemed to be relatively uncommon, although 21% of father payees reported that child support was neither paid in full nor on time. Parents who contributed jointly to decisions about their child were more likely than other parents to indicate full compliance.

Parents typically considered that their current child support payment was fair for themselves and for their child's other parent, although perceived fairness for themselves varied according to whether the parent was a payer or payee, the care-time arrangements in place, and decision-making practices. For example, a higher proportion of father payers than mother payees believed that the arrangements were personally fair, and among father payers, sense of fairness was lowest for those with equal care time, followed by those who never saw the child. Mothers whose child never saw the father were the least likely of all mother payees to report that child support payments were fair to them. In addition, parents who shared decision-making responsibilities about their child were more likely to describe their current child support payment as being fair compared with other parents.

However, when interpreting the findings on perceived fairness of the Child Support Scheme, it is important to bear in mind the data were collected just after the new Child Support Formula took effect in July 2008. This was therefore a transitional period for many parents.

3.8 Parental responsibility and time: Perspectives and practices of lawyers and other service providers

The principle that parents should share responsibility for their children after separation had very strong support from parents, family relationship service professionals and family law system professionals. However, many of the professionals involved in the provision of relationship services or the legal sector believed that problems arise from the way in which the concept of shared parental responsibility is expressed in the legislation. The SPR Act 2006 provides that the starting point for considering post-separation parenting arrangements is the presumption of "equal shared parental responsibility" (s61DA). Where orders are made following the application of this presumption, courts "must" consider making orders (s65DAA) for children to spend "equal" or "substantial and significant time" with each parent where this is found to be in a child's best interests (s65DAA(1)(a)) and reasonably practicable (s65DAA(1)(b)).

The presumption of equal shared parental responsibility is not applicable where there "are reasonable grounds to believe" there has been family violence or child abuse. Further, courts have the discretion not to apply the presumption in interim proceedings (s61DA(3)) and it is rebuttable where evidence is adduced to show its application would not be in a child's best interests (s61DA(4)). However, the paramount issue remains the best interests of the children (s60CA), meaning judges retain discretion to make orders they determine would be in a child's best interests after considering the facts of the particular case.

Many professionals in the family law system say that many parents, particularly fathers, believe that the law means they are "entitled" to 50-50 "shared care" in the sense of parental responsibility and time spent. Legal sector professionals, in particular, believe that these expectations are difficult to work with and have a number of consequences, including greater disillusionment with the system among fathers who find the law does not provide for 50-50 "custody", and increased difficulty in working with parents to achieve child-focused arrangements.

A majority of lawyers and family relationship service professionals indicated that it was not easy for parents to understand the difference between parental responsibility and time. They also reported that there is poor understanding among parents, and possibly some professionals, of the circumstances in which the equal shared parental responsibility presumption should not be applied or may be rebutted.

Many family relationship service professionals reported that a significant proportion of parents - particularly fathers - have expectations of 50-50 care when they first attend services, but in many of the cases where such arrangements are not appropriate, parents can be assisted to develop more appropriate agreements that can meet both their child's and their own needs. They also noted that some fathers may need additional support in creating a "child-friendly" or welcoming environment for their child. However, legal system professionals16 indicated that, in some cases, expectations of a 50-50 care-time entitlement among some fathers are difficult to shift. Many legal sector professionals said that since the reforms, negotiations and litigation over parenting arrangements had become more focused on parents' rights than children's needs. A focus on the primacy of children's best interests (SPR Act 2006 s60CA) is difficult to maintain when parents are concerned with what they perceive to be their own rights under the legislation. Data from analysis of court files reveal that just over a quarter of fathers who applied to court after the reforms for orders about care time sought equal care-time arrangements.

The Every Picture Tells a Story report indicated that there were perceptions in the community about an 80-20 rule in arrangements for children to spend time with their parents after separation, with mothers mostly having their child for 80% of the time.17 The evaluation data show that advice consistent with such a rule was provided by lawyers much less often after the reforms than prior to the reforms (FLS 2006 and 2009). Overall, lawyers and judicial officers said that post-reform there was more creativity evident in making care-time arrangements, with more effort being made to ensure that fathers were involved in special activities as well as their children's day-to-day routine (FLS 2006, QSLSP 2008). However, although lawyers have not changed the advice they give about the need for parents to be able to cooperate in order for a shared parenting arrangement to be of benefit to children, lawyers believe that, post-reform, more children are in shared care-time arrangements in circumstances of high conflict than before the reforms (FLS 2009).

Lawyers and family relationship service providers tended to see some key aspects of the reforms differently from each other. These differences are likely to reflect a number of issues, including the different professional obligations that lawyers and service providers have, the different contexts in which they operate and differences in their respective client bases. For example, family relationship professionals were generally positive about the policy framework's ability to facilitate the making of arrangements that were developmentally appropriate for children. In contrast, a substantial majority of family lawyers said that the legal framework did not facilitate the making of arrangements that were developmentally appropriate for children.

Many legal sector professionals believe the reforms have favoured fathers over mothers and parents over children, and that the post-reform bargaining dynamics are such that mothers are "on the back foot" (FLS 2008, QSLSP 2008). Some professionals in the legal sector pointed to a connection between child support liability/entitlement and a wish to increase or resist decreases in care time. Among lawyers, 68% agreed that some potential payers are trying to get more time with their children in order to reduce child support liability (FLS 2008). About a half (49%) of the lawyers who were interviewed agreed that some potential payees resist the child spending more time with the other parent in order to prevent a reduction in the amount of child support they receive. The majority of family relationship service professionals indicated that they thought child support was a motivation for no more than a quarter of their clients. While legal system professionals thought that the prevalence of this type of bargaining had increased following the 2006 family law reforms and 2008 changes to the Child Support Scheme, further work is needed to determine whether the prevalence has actually increased and if so to what extent.

Another issue identified by lawyers as being relevant to the positions some parents adopt in negotiating parenting arrangements relates to post-separation property division. Some lawyers maintained that some fathers were motivated to seek equal care-time arrangements in order to maximise their share of the post-separation property division (FLS 2008, QSLSP 2008). Overall, the data from the Family Lawyers Survey 2008 suggest there may have been a decrease in the average share of property allocated to mothers in post-separation property settlements after the reforms, with varying estimates of the shift varying, but with most being in the region of a five per cent decrease (e.g., from a 70-30 split in favour of mothers pre-reform to perhaps a 65-35 split in favour of mothers post-reform).

3.9 Family violence and child abuse: Parents' pathways and professionals' perspectives

The evaluation provides clear evidence that the family law system has some way to go in being able to respond effectively to family violence and child abuse. It also provides evidence of the 2006 changes having improved, in some areas, the way in which the system identifies families where there are concerns about family violence and child abuse. Specifically, there is evidence in the family relationship service sector and some parts of the legal sector that attempts to identify such families have become more systematic since the 2006 changes.

It is important to recognise that family relationship and legal sector professionals expressed a range of views about how well the system is working. It is also important to keep in mind when interpreting the evaluation findings about family violence that this is probably the most difficult area for any family law system to address. Many of the issues identified in the evaluation existed prior to the reforms.

The legislative changes introduced as part of the reforms placed greater emphasis on the need to protect children from harm and from exposure to family violence and child abuse (SPR Act s60B(1)(b), s60CC(2)(b)). Two other key aspects of the legislation that address these issues are: the exception to the requirement for parents to attend FDR where there is a risk of family violence (s60I(9)); and reasonable grounds to believe that there has been family violence by a parent being a reason for the non-application of the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility (s61DA(2)). As indicated above, systematic screening processes are in place across the family relationship services sector to identify matters involving family violence and child abuse, although screening occurs less systematically in the legal sector. The FCoA and the FCoWA screen routinely, but the FMC does not (although parties have the opportunity to draw safety concerns to the attention of court staff).

Lawyers and professionals who work in the relationship services sector indicated that concerns about family violence and child abuse and neglect are common among separating families. However, lawyers and relationship service professionals both expressed much greater confidence in the ability of the family law system to ensure that children had meaningful involvement with each parent than in its ability to ensure that children are protected from harm, family violence, child abuse and neglect.

Where at least one parent holds safety concerns (for themselves or their child) as a result of ongoing contact, parenting arrangements take longer than otherwise to resolve and entail the use of a greater number of different types of services. For instance, 48% of mothers and 55% of fathers who held safety concerns contacted at least three services, compared with 16% of fathers and 20% of mothers without such concerns (LSSF W1 2008).

Between 16% and 20% of parents with a shared care-time arrangement held safety concerns associated with ongoing contact with the other parent. The prevalence of safety concerns among these parents, however, was similar to that apparent among parents whose child spent most nights with the mother and among parents whose child saw the father during the daytime only.

Between a fifth and a quarter of parents who participated in the Survey of FRSP Clients 2009 reported experiencing fear of the other party when they were using the relationship service. Of these parents, around 35% (depending on the service attended) indicated that these concerns or fears were not addressed at the time of attending the service. Relationship service providers had high levels of confidence in their ability to identify and work with families experiencing family violence and child abuse. While the majority of clients thought that the service adequately dealt with their fear or safety concerns relating to the person about whom they attended the service, around one-third said that the service did not adequately respond.

Relationship service sector practice often means engaging with such families in ways that will ensure that safety concerns are also addressed via liaison with or referrals to other services specialising in areas such as mental health, addictions and family violence. These interventions can be in some tension with the perceived need to develop comprehensive parenting arrangements as a matter of priority. Family relationship sector staff spoke of assisting with "holding" arrangements for parents and children while some dysfunctional behaviours and attitudes were addressed.

Lawyers were largely confident in their own ability to screen for family violence and child abuse and neglect, but less confident (and largely unfamiliar with) the service sector's ability to do so. Both lawyers and service professionals expressed reservations about the adequacy of the family law system's response when concerns about family violence and child abuse are raised. Close to half the lawyers in the Family Lawyers Survey 2008 expressed the view that the legal system had not been able to adequately screen for family violence and child abuse.

A range of complex issues underlie the concerns that system professionals held about a lack of efficacy in handling family violence and child abuse and neglect across the system. Relevant issues include a lack of understanding of family violence and child abuse in various parts of the system and perceptions of there being pressure to reach agreements notwithstanding the presence of such concerns. Problems also stem from the intersection of the state and federal legal systems, and with lawyers (and family relationship sector professionals) finding child protection systems difficult to engage with when there are concerns about risks to children. These issues pre-date the reforms and are longstanding. Further, some professionals believed that some new aspects of the legislative framework have discouraged concerns about family violence and child abuse from being raised. These include an obligation of courts to make costs orders against a party found to have "knowingly made a false allegation or statement in proceedings" (SPR Act 2006 s117AB) and the requirement for courts to consider the extent to which one parent has facilitated the child having a relationship with the other parent (s60CC(3)(c)).

While there was widespread concern that family violence and child abuse and neglect are being inadequately responded to, some legal professionals and fathers also claimed that allegations about family violence and child abuse were being used to impede fathers' claims for a shared parenting role after separation.

3.10 Children's wellbeing

The move to encourage each parent to spend equal or substantial time with their child is based, at least in part, upon the view that there is benefit to many children from having a meaningful relationship with both of their parents and that substantial time with both parents can assist in this being achieved. However, the legislation also recognises that children need to be protected from harm and from exposure to abuse and family violence.

To what extent do children benefit from "equal" or "substantial and significant" time with each parent? There is strong evidence that the quality of children's relationships with their parents is important to child outcomes. Exposure to inter-parental relationships characterised by high levels of acrimonious conflict, or by fear, safety concerns or physical harm clearly jeopardise children's wellbeing. However, while the development and maintenance of a close relationship requires spending time together (typically through face-to-face interaction), the existing literature suggests that "more time" does not necessarily equate with better outcomes for children.

Concerns have been raised as to whether shared care-time arrangements exacerbate any negative impacts of parental separation on children's wellbeing if their parents are locked in a high level of conflict or have a history of violence. Concerns have also been raised about whether substantial (shared) care-time arrangements are detrimental to the developmental needs of very young children.

As part of the evaluation, the impact of the following aspects of children's post-separation experiences on their wellbeing was assessed:

- care-time arrangements;

- the quality of inter-parental relationship post-separation;

- safety concerns post-separation; and

- the existence of violence pre-separation.

The analysis was primarily based on data from the LSSF W1 2008 and was supplemented by data from the first three waves of the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC).

While the LSSF W1 2008 has the advantage of providing a large sample of children and their families, its main limitation is that information on child wellbeing is entirely based on parents' reports. The LSAC survey, on the other hand, is based on a much smaller number of children whose parents have separated, but information on child wellbeing is derived from parents, teachers and the children themselves.

Regression modelling was used to estimate the impact of different care-time arrangements on the wellbeing of children, while taking into account (i.e., holding constant) the impact of other variables likely to affect children's wellbeing (e.g., parental educational attainment, labour force status, and country of birth). The regression modelling framework was used to estimate whether the impact of different care-time arrangements depends upon: (a) the quality of the parental relationship post-separation; and (b) whether there is a history of violence.

Analysis of both the LSSF W1 2008 data and LSAC studies suggest that, compared to the outcomes of those who spent 1-34% of nights with their father or had daytime-only care with the father, children's outcomes were similar (or perhaps marginally better) in shared care-time arrangements, while children who never saw their father appeared to fare worse.

While a history of family violence and highly conflictual inter-parental relationships appear to be quite damaging for children, there was no evidence to suggest that this negative effect is any greater for children with shared care time than for children with other care-time arrangements. It remains possible, however, that the measures adopted in this analysis were insufficiently sensitive to detect existing effects in these areas.18 Longitudinal research based on a relatively small clinical sample of high-conflict separating families (McIntosh, 2009) found that, compared to other parenting arrangements, a pattern of shared care sustained over more than 12 months was associated with a greater increase in the already negative impact on children of highly conflictual inter-parental relationships and the negative impact of circumstances in which one parent holds concerns about the child's safety.

When the measure of family violence is whether the mother expressed safety concerns, analysis of the LSSF W1 2008 reveals that shared care time exacerbates the negative impacts on children. Where this situation existed, children in shared care-time arrangements fared worse, according to mothers' assessments, than those who stayed with their father for only 1-34% of nights. The presence of safety concerns was associated with lower child wellbeing in all care-time arrangements. These findings are consistent with the findings of other researchers.

3.11 Grandparenting and the family law reforms

Most parents with a child under the age of 18 years agreed that it is important for children whose parents have separated to maintain the same level of contact with their grandparents that they had before the separation. The majority of parents, but especially mothers, also thought that their children had a close or very close relationship with their grandparents.19

Most separated parents in 2006 thought that the relationship between their own parents and their children was close or very close, but non-resident fathers were least likely to think this. In addition, non-resident fathers in 2009 were the least likely to rate their own parents as being very involved or quite involved in their children's lives.

Maternal grandparents whose grandchild lived mostly with the mother were the most likely to report close or very close relationships with their grandchild and to indicate that they spent time with their grandchild at least once a week, while paternal grandparents whose child lived mostly with the mother were the least likely to report such circumstances. A similar pattern was evident when parents were asked about the child-grandchild relationship.

Reports of parents and grandparents also suggested that such trends at least partly resulted from the impact of children's care-time arrangements after parental separation. For example, non-resident fathers and paternal grandparents whose grandchild lived with the mother were the most likely of the groups examined to indicate that relationships had become more distant as a result of separation.

There is some evidence to suggest that parenting arrangements are now more likely to take into account children's time with grandparents than was the case prior to the reforms. Just over half the post-reform separated parents who had sorted out their parenting arrangements and a similar proportion of grandparents felt that time with grandparents had been taken into account. Pre-reform separated parents, on the other hand, were less likely to have taken grandparents into account (40%) than after the reforms.20

Only a minority of grandparents made use of services in relation to the separation and, where services were used, lawyers and legal services were used considerably more often than any other source of formal assistance. Paternal grandparents were considerably more likely to seek the support of services than maternal grandparents. Few grandparents in the focus groups had knowledge or understanding of the range of services available.

Interviews and surveys with FRSP staff revealed a growing appreciation of the importance of including grandparents in the negotiations and discussions, where appropriate. Many lawyers, too, indicated they had advised grandparents who sought advice about contact with grandchildren that they were in a stronger position under the new legislation (FLS 2008). There was also an appreciation by FRSP staff of the complexity of some extended family situations, and the need to avoid automatically assuming that involvement of grandparents would contribute positively to the children's lives. The stories from the grandparents' focus groups reflected this complexity.

In summary, the overall picture is of grandparents being very important in the lives of many children and their families, with some evidence that the legislation has contributed to foregrounding this. Clearly, grandparents can also be an important resource when families are struggling during separation and at other times. But as complexities increase in particular families, dispute resolution and decision-making in cases involving grandparents are likely to prove difficult and time-consuming.

3.12 The 2006 reforms and the courts

Three main courts exercise jurisdiction in disputes involving separated families. Only one state, Western Australia, has its own state-based court, the Family Court of Western Australia. The other states and territories are served by the Family Court of Australia, established in 1976, and the Federal Magistrates Court, which began operating in 2000. The FCoA and FMC operate in parallel, although the FCoA is a specialist family law court and the FMC also exercises jurisdiction in a range of federal law areas. The more "complex" family law work is meant to be handled by the FCoA, but it is evident that both courts handle a high number of matters involving family violence and/or child abuse and a range of dysfunctional behaviours. More allegations concerning child abuse are made in the FCoA, though such allegations are still prevalent in FMC matters.

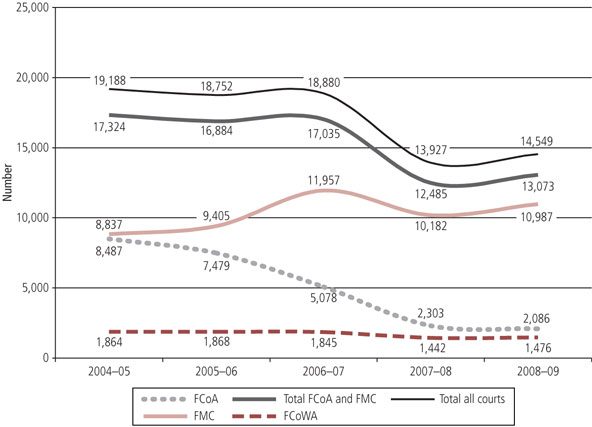

While the number of applications for final orders relating to children's matters that were made to the FMC between 2005-06 and 2008-09 increased, this increase was more than offset by the decrease in the total number of such orders that were lodged across the system. Specifically, the overall number of such applications declined by 22% from 18,752 in 2005-06 to 14,549 in 2008-09 (Figure 2). The number of applications to the FCoA declined by 72% from 7,479 to 2,086 over this period and the number to the FMC increased by 17% from 9,405 in 2005-06 to 10,987 in 2008-09 and the number of applications to the FCoWA decreased by 21% from 1,868 to 1,476.

Figure 2 Number of applications for final orders, by court, 2004-05 to 2008-09

Note: Includes children only and children plus property matters.

Source: FCoA, FMC, FCoWA administrative data 2004-09

It should also be noted, however, that applications for final property orders increased post-reform, reversing a pre-reform trend towards stability. Further investigation is required to determine whether there is a causal connection between these trends and the 2006 family law system changes.

In the post-reform period, a pre-existing trend for more matters to be filed in the FMC and fewer in the FCoA gained momentum, with filings in the FMC in all relevant categories (children only, children and property, property only) increasing as FCoA filings decreased. While there is a range of reasons for the change in filing patterns between the courts, it mainly appears to be linked to changes in the allocation of resources (i.e., judicial officers) between the two courts, with the number of federal magistrates increasing and the number of FCoA judges decreasing.

In each court, the number of Form 4 notices21 that were filed increased as a proportion of filings. In the FCoA, the proportion of matters where Form 4 notices were filed increased from 9% in 2004-05 to 21% in 2008-09. In the FMC, filings of Form 4 notices increased from 4% of matters in 2004-05 to 8% in 2008-09 and in the FCoWA increased from 11% of matters in 2004-05 to 23% in 2008-09.

In the post-reform period, the proportion of matters where an order for an independent children's lawyer (ICL) was made also increased in both the FMC and FCoA (FCoWA data were not available). For example, in 2004-05, about 19% of FMC and FCoA matters had such orders made, compared with 33% in the FCoA and 34% in the FMC in 2008-09.

Legal system professionals who participated in the QSLSP 2008 and the FLS 2008 raised a number of concerns about the parallel operation of the FMC and FCoA. These included the implications for parents and practitioners of there being two courts administering the same legislation on the basis of two very different sets of processes. One issue stemming from this was that the FMC provided practitioners who preferred to operate in a traditional adversarial model with a forum in which to do this. This issue has particular significance when it is considered that some 84% of children's matters were dealt with in the FMC in the post-reform period in states and territories other than Western Australia.

The FMC was valued for its quicker, cheaper service, and it was acknowledged that there were excellent federal magistrates. However, there were also concerns about the time pressures under which federal magistrates operate, their heavy caseload and the fact that some federal magistrates did not have a family law practice background. There were also concerns expressed by family consultants, judicial officers and lawyers about the role played by family reports (provided by social workers or psychologists) in bringing about settlements of parenting matters in the FMC. These concerns arise from the fact that some parenting disputes in the FMC are being settled on the basis of family reports, which are not examined through legal processes. This means that factual issues, such as allegations of family violence and child abuse, are not tested in court. This is not necessarily relevant in all cases, but it was a concern commonly expressed.

Some federal magistrates were perceived to be more inclined to adopt a literal interpretation of the SPR Act 2006, meaning that some outcomes may not have sufficiently taken into account the needs of children, particularly those in younger age groups. There was also concern that time pressures inhibited the effective scrutiny of allegations of family violence and child abuse. The quantitative data from the studies of FCoA, FMC and FCoWA court files post-1 July 2006 court files indicate some variation in patterns of outcomes between the three courts, although perhaps not as large as suggested by some professionals in the qualitative study.

It is important to note, though, that in formulating advice for clients, lawyers are trained to look at the range of possible outcomes suggested by decisions handed down in matters that may have similar fact situations. This training means that they tend to be particularly attuned to differences in approach between decision-makers and this will influence the advice they give clients and their views as to how the law is being applied.

Transfers were also seen to be a difficulty, with federal magistrates seen as being reluctant to transfer matters to the FCoA, even those involving family violence and child abuse. As a result of the different case management systems operating in the three courts, matters in the FCoA and the FCoWA are subject to routine screening for family violence, child abuse and other complex issues, but those filed in the FMC are not.

3.13 The implementation of Division 12A of Part VII: Principles for conducting child-related proceedings

One of the aims of the 2006 reform package was to ensure that matters that proceeded to court were resolved in a more child-focused way. To this end, Division 12A of Part VII was introduced, outlining a series of "Principles for conducting child-related proceedings". These principles were based on some aspects of a new case management system the FCoA had piloted, prior to the reforms, in its Children's Cases Program (Harrison, 2007). This approach was intended to reduce adversarialism and increase the child focus in child-related matters. Both the FCoA and the FCoWA changed their case management approaches to support the introduction of Division 12A of Part VII. The models differ in some respects, but both involve family consultants having initial contact with the families to allow early assessment of the issues and to conduct screening. The FMC did not have the family consultant resources to change its model, although its approach of active judicial management is seen as being consistent in some aspects with Division 12A of Part VII. The evaluation considered the FCoA, FCoWA and FMC processes as part of a much larger set of questions concerning the impact of the reforms and, for this reason, the insights provided by the evaluation should be considered to be exploratory.

Division 12A of Part VII of the SPR Act 2006 articulates in legislation the duties and powers of the court (and the principles that guide the application of these duties and powers) to manage proceedings relating to parenting orders. Key principles include that:

- the court must consider the needs of the child and impact of proceedings upon them in determining the conduct of the proceedings (s69ZN(3));

- the court is to actively direct, control and manage the proceedings (s69ZN(4));

- the proceedings should be conducted in a way that safeguards the child against family violence, child abuse and neglect, and the parties to the proceedings against family violence (s69ZN(5));

- the proceedings are to be conducted in a way that promotes cooperative and child-focused parenting by the parties (s69ZN(6)); and

- the proceedings are to be conducted without undue delay and with as little formality and legal technicality as possible (s69ZN(7)).

The duties articulated in Division 12A include:

- deciding which issues may be disposed of summarily and which require full investigation (s69ZQ(1)(a));

- deciding the order in which issues should be decided (s69ZQ(1)(b)); and

- giving directions and making orders regarding procedural steps (s69ZQ(1)(c)), subject to deciding whether a step is justified on the basis of likely benefits considered against the cost of taking it (s69ZQ(1)(d)).

Powers set out in Division 12A include the ability, at any stage after a matter has commenced and prior to final determination, to:

- make a finding of fact (s69ZR(1)(a));

- determine a matter arising from the proceedings (s69ZR(1)(b));

- make an order in relation to an issue arising out of the proceedings (s69ZR(1)(c)).

A majority of legal system professionals (who participated in the QSLSP 2008 and the FLS 2008) supported the child-focused principles inherent in Division 12A of Part VII and many of these participants expressed concerns about its lack of availability in areas not serviced by the FCoA.

While family consultants and judges mostly viewed Division 12A of Part VII (and the case management models that accompanied it in the FCoA and the FCoWA) as a positive step, lawyers were more cautious. Judges welcomed the increased flexibility in powers to decide which issues should be determined, at what stage of proceedings they should be determined and what evidence should be filed. Family consultants indicated the process had improved child focus.

Data from the FLS 2006 and 2008 indicate that 58% of family lawyers agreed in 2008 that Division 12A was a desirable change, compared with 60% in 2006. A consistent and substantial minority (29% in both years) disagreed that the change was desirable. Divided views were evident in relation to other aspects of Division 12A as well, with 40% of lawyers in 2008 agreeing that it produced better outcomes for children, compared with 34% disagreeing. Similarly, 43% of lawyers in 2008 agreed that Division 12A processes allowed sufficient flexibility to deal with family violence and child abuse, compared with 37% disagreeing.

Lawyers raised a range of concerns about Division 12A of Part VII as it had been implemented in the FCoA, including concerns about more court events leading to increased costs, more delays, inconsistent judicial approaches to the exercise of powers22 and the disadvantages of having inarticulate or uneducated clients speaking to the judge. Similar concerns were expressed in relation to the FCoWA model, but these were not as numerous or substantial.

In relation to both the FCoA and the FCoWA models, some lawyers indicated that the process benefited clients by allowing them an opportunity to speak directly to the judge and thus to feel heard. Lawyers also valued the social science input of family consultants in the FCoA and FCoWA models.

3.14 The application of the SPR Act 2006 amendments to the Family Law Act 1975

The amendments to Part VII of the FLA made by the SPR Act 2006 (Cth) are seen to have produced a legislative pathway that is complex and convoluted and not easily understandable by parents and some system professionals. Judges who participated in the QSLSP 2008 indicated that judgments were taking longer to write because of the increased number of provisions to consider. Lawyers said advice-giving is more difficult and time-consuming, with parents finding the law difficult to comprehend, and cases taking longer to prepare. The legislative pathway that must be followed in making decisions requires judicial officers to apply numerous provisions (including s60CC(2), s60CC(3), s60DA, s65DAA) to the facts and this complexity is considered by many professionals to obscure the primacy of the "best interests" (s60CA) principle, particularly in arrangements made by negotiation.

The application of the presumption in interim hearings on the basis of little evidence was also seen as problematic. A key post-reform judgment, which outlines an 11-step process to be followed in applying the legislation (Goode and Goode (2006) FamCA 1346), even on an interim basis, underlines the complexity in applying the legislation. While court-based decisions demonstrate a variety of approaches to parental responsibility and time orders, reflecting case-by-case decision-making on the basis of the best interests principle (SPR Act 2006 s60CA), community understandings of the law as providing for "50-50" outcomes on the basis of the presumption highlight the confusion engendered by some aspects of changes to the parenting provisions.

4 Implications of the findings for the key evaluation questions

This evaluation has shown that a significant proportion of families who actively engage with the family law system have complex needs and are affected by issues such as family violence, child abuse, mental health problems and substance misuse. Such families are the predominant clients both of post-separation services and the legal sector.

1. To what extent are the new and expanded relationship services meeting the needs of families?

(a) What help-seeking patterns are apparent among families seeking relationship support?

(b) How effective are the services in meeting the needs of their clients, from the perspective of staff and clients?

There is evidence of fewer post-separation disputes being responded to primarily via the use of legal services and more being responded to primarily via the use of family relationship services. This suggests a cultural shift whereby a greater proportion of post-separation disputes over children are being seen and responded to primarily in relationship terms.