Welfare reform in Britain, Australia and the United States

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

September 1999

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

In the United States, radical welfare reform now leaves individuals with no alternative to finding and keeping a job, and the government has forced lone parents into employment whether they want it or not. Although the principle of 'mutual obligation' lies at the heart of recent welfare reforms in Britain and Australia too, the policies that have been adopted so far have been much less dramatic than in the US, particularly with regard to the welfare rights of lone parents. Eventually, however, Britain and Australia will have to confront the same tough choice which the Americans have faced: do we want to defend the right of lone parents to choose not to work, or do we really want to reduce the levels of welfare dependency? (Journal abstract)

In the United States, radical welfare reform now leaves individuals with no alternative to finding and keeping a job, and the government has forced lone parents into employment whether they want it or not.

Although the principle of 'mutual obligation' lies at the heart of recent welfare reforms in Britain and Australia too, the policies that have been adopted so far have been much less dramatic, particularly with regard to the welfare rights of lone parents.

Eventually, however, Britain and Australia will have to confront the same tough choice which the Americans have faced: do we want to defend the right of lone parents to choose not to work, or do we really want to reduce the levels of welfare dependency?

Over the last couple of years in Britain, welfare policy has been subjected to one of the most radical rethinks since the publication of the Beveridge Report in 1942. The reforms that have emerged from current thinking are based on the British Labour government's espousal of a new set of ideas about social issues.

Influenced by a number of respected thinkers (including Frank Field and Lawrence Mead), New Labour has adopted a philosophy emphasising the reciprocal obligations of citizenship, and has argued for a new 'contract' between the state and the individual: 'The new contract is essentially about duty. Duties on the part of Government are matched by duties of the individual' (DSS 1998: 8).

It is claimed that past welfare policies encouraged passivity and dependency by paying benefits without placing sufficient demands on the recipients to find work. New Labour hopes that by requiring recipients to enter into a contract it will encourage much more active participation in job search, and in education and training schemes. As people are helped into work they will also move off welfare and into self-sufficiency. By emphasising the mutual obligations of the citizen and the state it is hoped that a more inclusive and cohesive society can be created where everyone pulls together in the interests of the community.

This new way of thinking is said to represent a 'Third Way' which rejects 'old' Labour's rights-based welfare philosophy, as well as the individualistic and market-led welfare policies of the Conservative Party. New Labour rejects the dependency and passivity that 'old' Labour policies allowed, and it rejects the minimalist role of government towards joblessness and dependency that the Conservative governments of the 1980s adopted. Instead, both individuals and the state are expected to take an active role in securing escape from joblessness and dependency - and the primary way of achieving this escape is to be through steady employment.

British commentators have made much play of the innovativeness of New Labour's thinking. What many do not realise is that the policies that have emerged are very similar to the reforms that have been taking place in Australia in recent years. In fact, the major policy reform that the British government has introduced to deal with the problem of joblessness and welfare dependency - the New Deal - is heavily derivative of the past Australian Labor government's 'Working Nation' reform and the more recent Coalition government's 'Work for the Dole' program. In turn, these reforms can be traced back to the United States 'workfare' reforms.

The basic principle underlying all of these policies is the notion of 'reciprocal obligations'. Under this philosophy a deal is struck between the state and the individual whereby the state pays benefits and is pro-active in helping individuals back into work, in return for which individuals must meet their obligations of participating in the various schemes and searching for work.

Welfare dependency and lone parents

Changes in welfare policies or in approaches to joblessness are likely to have direct consequences for the family. The most obvious example of this relates to lone parents, most of whom depend to a greater or lesser extent on welfare support. In Britain, Australia and the United States, the numbers of lone parents claiming welfare support have risen sharply over the last thirty years, and in all three countries it is reasonable to suppose that lone parenthood could not have expanded to the extent that it has unless governments had provided cash support.

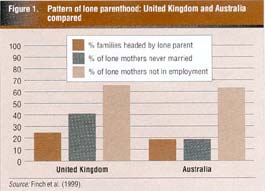

Welfare dependency among lone parents has been rising in both Britain and Australia, but the trend is much stronger in Britain. As Figure 1 shows, Britain is now has a very high rate of lone-parenthood (a third higher than in Australia), a high rate of never-married mothers (more than double Australia's rate), and a high rate of joblessness. In absolute terms the numbers in Britain are even more striking. Latest estimates show that 1.6 million families are headed by a lone parent, affecting 2.8 million children (Haskey 1998), while the social security bill for the 1.3 million dependent on welfare amounts to about £10 billion (about A$25 billion) (DSS 1999). Furthermore, spells on benefit for lone mothers are rarely brief. A recent study found that 43 per cent of lone mothers had been in receipt of the basic welfare benefit (Income Support) continuously for more than six years (Finch et al. 1999).

Figure 1. Pattern of lone parenthood: United Kingdom and Australia compared

In the United States, the recent Clinton welfare reforms focused directly on the major benefit for lone mothers, 'Aid to Dependent Families with Children'. In 1996 this was replaced by 'Temporary Assistance for Needy Families' (TANF). As the name of the benefit implies, TANF is designed to be temporary; it limits families to two years on welfare in any one spell, and to a total of five years welfare. The clear message is that benefits are finite and cannot be seen as a long-term income source equivalent to work or to a father's earnings.

Another message the reform conveys is that welfare is not a right. In return for TANF, recipients need to meet tough job-search and training obligations. The immediate aim of TANF is to get lone mothers into work and off benefits as soon as possible, and welfare agencies are extremely pro active in organising this. Lying behind this aim is the desire to reduce the number of out-of-wedlock births.

The belief seems to be that, by placing obligations on lone mothers to find work and get off benefits, there will be positive secondary consequences in achieving greater parental responsibility and strengthening family stability. One way this may work is by deterring many women from having births out of wedlock in the first place. Prospective lone mothers now know that they cannot expect to be provided for by the state; they must either find work or find a husband willing to support them and their child. Another way it may work is by increasing the incentives of those who are lone mothers to marry, for it is only by finding a new and committed partner that they can now choose to stay at home and care for their child rather than go out to work full-time.

The evidence from America is that these reforms are having their desired effect. In the state of Wisconsin, where tough welfare to work policies have been in existence for some time, there has been an 18 per cent fall in the number of ex-nuptial births to black Americans between 1990 and 1996, and between 1993 and 1998 there has been a 40 per cent drop in the number on welfare (Murray 1999: 7).

Comparing Britain and Australia with the USA

The idea of enforcing work obligations and getting people to take more responsibility for their lives is also a theme that runs through recent Australian and British welfare reforms. The Australian Work for the Dole reform is based on the principle of mutual obligation - that in return for welfare, unemployed people have the obligation to seek work actively and strive to improve their competitiveness in the labour market. Similarly, in Britain the New Deal reform seeks to establish a new 'contract' between citizen and state, with rights matched by responsibilities (DSS 1998). Although not as tough as the Clinton reforms, under Work for the Dole and the New Deal both the employment agencies and the unemployed are obliged to take a much more active role in finding work. Young people who have been unemployed for longer than six months are automatically placed on the schemes and they are required to supplement their job searching with training, education, community work or subsidised employment. Welfare claiming without job seeking and job training is not tolerated and benefit sanctions are applied.

Despite these common themes, however, there are two crucial differences between the three countries. One difference lies in what is deemed to be stopping the jobless from working. Whereas the American (and increasingly the Australian) reforms assume that the major factor in joblessness is lack of personal motivation to find or take work, the British reforms assume that joblessness results from certain external barriers that individuals face.

The other major difference is the overall aim of the reforms. The Clinton reforms aim to cut the numbers on welfare, which in turn, it is hoped, will reduce the number of exnuptial births and deter lone parenthood. In contrast, the British New Deal and Australian Work for the Dole reforms do not seek to push lone parents into work and off welfare. In both countries, the sorts of obligations that have been imposed on other claimant groups (such as the young unemployed) have not so far been extended to cover sole parents, and both governments have been careful not to appear to be attacking this group.

These two differences have a fundamental impact on the way the policies have been implemented, as well as on the likelihood of their success. Let us consider each in turn.

Low work motivation versus barriers to employment

According to the British Labour Government's 1998 welfare reform green paper, worklessness occurs because, 'People face a series of barriers to paid work' (DSS 1998: 1). For the unemployed the major barrier is presumed to be the mismatch between the skills and education they have and the level of skills and education expected by potential employers.

Reflecting this assumption, the government has essentially copied the reforms of the past Australian Labor government by making training, education and job placements the centrepiece of the New Deal for the unemployed. The emphasis is not on getting the jobless into work as soon as possible, as is true of the Clinton reforms, but in educating and training unemployed people in order to prepare them for work. Whereas the American reforms assume that it is work motivation that is lacking, the British reforms assume that the jobless would willingly take work it if only the barriers to employment were not there.

The same assumption applies for lone mothers as for the unemployed: lone mothers want work but barriers stop them from finding work. Not only do lone mothers face skill barriers but there are financial and child care barriers as well. The financial barrier is that lone mothers are not working because they will be no better off in work than if dependent on benefits. The child care barrier is that lone mothers cannot work because there is a lack of child care facilities and they lack the money to pay child care costs.

In order to lessen the financial barrier to employment the British government has introduced the Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC). This in-work benefit reduces the taper in benefit withdrawal for those who find work so that work always pays better than benefit dependency. In fact the incentive to work is very strong, with WFTC offering a guaranteed minimum income of £180 ($450) per week for a full-time worker. In order to lessen the child care 'barrier' the government has introduced the Childcare Tax Credit which provides financial help to cover 70 per cent of child care costs for low- and middle-income families.

However, the problem with these policies is that there is little evidence that 'barriers to work' really are the major cause of continuing joblessness. It is difficult to see how lack of skills could be the problem, for example, when labour force participation rates have dropped sharply across all social classes in America and Britain (Jencks 1990; Nickell and Bell 1995). Regardless of skill and education levels, men are less likely to be participating in the labour force.

Joblessness and dependency seem to be more closely related to personal choice than to lack of opportunity. As Layard et al. (1994: 16) have argued, in Britain, 'Even when unemployment is high, there are not queues for all vacancies . . . if people are unemployed, it is generally because they have decided against these jobs'. Undoubtedly, people with fewer skills and lower education have unequal opportunities in finding the best work, but they are not excluded from work altogether, as the British government assumes.

Even where lack of skills is the problem, moreover, the British government is far too optimistic about the likely success of training and work experience programs in getting people into work. As a recent OECD report found, in respect of those who had not been in regular employment for a long time, 'the effectiveness of generalised training or work experience programs with these groups has been found to be low' (OECD 1998: 126). Instead, evidence from the United States suggest that the success of such schemes is more closely related to the obligations it imposes on finding work: 'The major determinant of whether clients enter jobs . . . is simply whether the program expects them to; the labor market and the skills of the clients are secondary' (Mead 1987: 13).

Just as suspect is New Labour's claim that financial barriers stop lone parents from working. The government set up WFTC in order to overcome the financial disincentives of work by 'making work pay'. However, in the United States evidence of such in-work benefits casts doubt on their effectiveness. Ellwood and Summers (1986: 96) found take-up to be low because 'welfare mothers do not seem to be very sensitive to work incentives'.

Neither is there much evidence that child care 'barriers' stop lone mothers from working. According to a study of 850 lone parents in Britain, 'child care was not the major barrier for the majority of lone parents' (Ford 1997: 63). Rather, as Hakim (1995) has argued, many women simply want to stay at home and bring up their children themselves. Moreover, if women do want to work, arranging child care seems to be much less of a barrier than commentators often suppose. For example, the country in Europe with the highest full-time rate of female employment - Portugal - is also the country with non-existent child care services (Hakim 1995: 438).

An evaluation of the New Deal pilot scheme funded by the Department of Social Security found that financial and child care barriers are of much less importance than self imposed barriers. As Finch et al. (1999: 53) note: 'Many did not want to work "yet", deciding instead to focus on their role as a parent.' Contrary to New Labour's assumption that lone mothers are queuing up to work, the researchers found that as many as 78 per cent of them did not even take up the offer of an interview with a New Deal adviser.

Now that the New Deal has moved beyond the pilot stage the results look even less convincing. The figures for January 1999 showed that since the program was set up, 163,383 letters have been sent to lone parents inviting them for an interview, but only 6,262 (3.8 per cent) have got jobs. Furthermore, a fifth of lone parents who did get jobs left them after six months (The Independent 1999).

The Working Nation scheme initiated by the Australian Labor government was also premised on the need to help the jobless overcome barriers. However, the results were mixed. Training and educating the unemployed did not open up a new vista of opportunities for employment as was hoped. In fact, as few as 22 per cent of those Job Compact participants were in unsubsidised employment three months after leaving their placements (Finn 1999: 61). Instead, the evidence suggested that a large amount of 'churning' was going on where the unemployed would go through the system only to find themselves back collecting benefit again at the end. Furthermore, many of the employers in the scheme who offered temporary job placements were negative about the work attitudes of the unemployed (DEET 1996: 91).

In response, the Australian Coalition government's Work for the Dole reforms adopted a tougher set of policies that shifted the emphasis away from the need for help in overcoming barriers to the need for the unemployed to find work at the earliest opportunity. This reflects the idea behind policy reforms in the United States that education and training is less important than getting the jobless to be motivated about finding work. Accordingly, spending on training programs has been reduced and obligations of job search have been increased.

Work of some kind is a condition of benefit payment, and for those who fail to meet this obligation the penalties are tough - much tougher than in the British New Deal. Non-compliance with the various job-search requirements can result in the non-payment of benefits for up to 26 weeks. And in order to check that the jobless are complying with their obligations to find work, case managers carefully scrutinise the job search diaries compiled by every client. Work for the Dole does not allow the jobless to 'free-ride' by collecting benefits without also making strenuous efforts to find work. According to a recent OECD report on welfare systems, Work for the Dole amounts to 'a 'zero tolerance' approach to long-term unemployment' (OECD 1998: 81).

Welfare reform and lone parent welfare dependency

In Britain, participation in the New Deal is entirely voluntary for lone parent benefit claimants - they are simply sent a letter asking them to attend an initial interview with an adviser. Although the overall goal is to promote movement from Income Support to paid work, there is no compulsion placed on lone mothers to seek work or even take up suggestions regarding courses that could help improve skills or education. In fact, it is still the case that lone mothers do not even have to attend the initial interview (although this will be changed in 2000).

In reality the New Deal for lone parents is a one-way deal: offers of help in training, education and job search are provided without any expectation on the part of lone parents that they participate. Reflecting this, the advice on the government's Web page to lone mothers states: 'It's entirely up to you to choose whether to join New Deal' (http://www.newdeal.gov.uk/english/ engtxt.asp). A major reason for this arrangement is that the government thinks lone parents should have a choice about whether or not they wish to work. British New Deal advisers simply 'provide a "tailored" package of help and advice on jobs, benefits, training and child care' (Finch et al. 1999: 13). This contrasts sharply with the situation in the United States where the TANF advisers' primary role is to get lone mothers into paid work and off benefits as soon as possible.

Lone parenthood usually implies welfare dependence (because lone parents are rarely able to earn enough to support themselves and their child). The recent American welfare reforms, which have withdrawn the right to infinite welfare, have thus effectively undermined the long-term economic viability of lone parenthood. This is not something which New Labour in Britain is prepared to countenance. Although its stated aim is to 'rebuild the welfare state around work' (DSS 1998: 23), the Blair government is unwilling to enforce work obligations and place limits on welfare claiming because it does not want to be seen to be attacking lone parents.

New Labour is therefore caught in a dilemma. It wants to reduce joblessness and dependency, but it is not prepared to withdraw support for a form of family life which for most people inevitably leads to joblessness and dependency. Because lone-parent families are rarely economically viable, this means that the only remaining way to get lone mothers back to work is by subsidising them. This has in turn entailed the introduction of a very costly in-work benefit, WFTC, which tops up in-work earnings. But these sorts of in work benefits run the risk of recreating 'in work the poverty and dependence they are supposed to abolish out of work' (Marsh 1997: 126). Put another way, the price of getting lone parents back into work is continued benefit dependency.

Conclusion

Clearly, governments cannot have it all ways. It is not possible to have large numbers of lone parents in work and self sufficient. Either governments adopt the American approach, which enforces work obligations and places limits on welfare entitlements at the cost of making lone parenthood a non viable lifestyle choice, or they adopt the approach of supporting free choice in family arrangements, at the cost of long-term dependency among those who choose lone parenthood.

In Australia, recent proposals have emerged to extend the scope of Work for the Dole to include lone mothers. Lone mothers who have been collecting welfare for more than five years and those who have recently left work to go on benefit are now obliged to attend an interview to discuss ways of getting them back into work. Furthermore, some will now have to pass a work activity test in order to obtain benefits. The obligations are nowhere near as demanding as for the unemployed, but the same philosophy of making people self-sufficient exists.

In contrast with the British government's belief that help to lone parents should be about advising them on the options and permutations of work and the claiming of welfare available to them, the explicit aim of the Australian proposals is 'to further promote the shift to a culture of self reliance and personal responsibility'.

As Australian Prime Minister John Howard has made clear, the family is the route to this goal: 'The stable functioning family still represents the best social welfare system that any community has devised and certainly the least expensive.' In other words, the Australian government is coming to recognise the link between welfare, independence and the family in a way that the British Labour government is still unwilling to do.

References

- DEET (1996), Working Nation: Evaluation of the Employment, Education and Training Elements, EMB Report, Canberra.

- DSS (1998), New Ambitions for Our Country, Stationary Office, London.

- DSS (1999), Social Security Statistics, Stationary Office, London.

- Ellwood, M.J. & Summers, R. (1986), 'Is welfare really the problem?', The Public Interest, vol. 83, pp. 57-78.

- Finch, H. et al. (1999), New Deal for Lone parents: Learning from the Prototype Areas, DSS Research Report 92, HMSO, London.

- Finn, D. (1999), 'Job guarantees for the unemployed: lessons from Australian welfare reform', Journal of Social Policy, vol. 28, pp. 53-71.

- Ford, R. (1997), 'The role of child care in lone mothers' decisions about whether or not to work', in DSS Research Yearbook 1996/97, HMSO, London.

- Hakim, C. (1995), 'Five feminist myths about women's employment', British Journal of Sociology, vol. 46, pp. 429-47.

- Haskey, J. (1998), 'Families: their historical context, and recent trends in the factors influencing their formation and dissolution', in E. David (ed.) The Fragmenting Family: Does it Matter?, Institute of Economic Affairs, London.

- Jencks, C. (ed.) (1990), The Urban Underclass, Brookings Institute, Washington DC.

- Layard, R., Nickell, S. & Jackman, R. (1994), The Unemployment Crisis, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Marsh, A. (1997), 'Lowering barriers to work in Britain', Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, vol. 8, pp. 111-35.

- Mead, L. (1987), 'The obligation to work and the availability of jobs: a dialogue between Lawrence M. Mead and William Julius Wilson', Focus, vol. 10, pp. 11-9.

- Murray, C. (1999), 'The underclass hasn't gone away', The Sunday Times, News Review Supplement, p. 7.

- Nickell, S. & Bell, B. (1995), 'The collapse in demand for the unskilled and unemployed across the OECD', Oxford Review of Economics, vol. 11, pp. 40 62.

- OECD (1998), The Battle Against Exclusion, OECD Publications, Paris.

- The Independent (1999), 'Tories decry "failed" New Deal scheme: social security, 14 March.

Alan Buckingham is Lecturer in Sociology in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Sussex, England. He recently completed his doctoral thesis on the underclass in Britain, some of which has been published as 'Is there an underclass in Britain?' British Journal of Sociology, vol. 50, 1999, pp. 49-75.