Family size

Men's and women's aspirations over the years

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

While most people across all ages want two or three children, little is known about how entrenched these preferences are. Do people modify their view about their ideal family size? In the Fertility Decision Making Project of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, respondents who were 22 years or older were asked about the number of children they would ideally like to have, and the number they had wanted when they were 20 years old. The article first explores the apparent extent to which men's and women's views about having children and their ideal family size had changed since they were 20 years old, and the direction of any such change. The various patterns of reasons for revised preferences are then outlined.

While most people across all ages want two or three children, little is known about how entrenched these preferences are. Do people modify their views about their ideal family size?

The Fertility Decision Making Project conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies in 2004 suggests that, whether in their early twenties, late thirties or somewhere in between, Australians want much the same number of children, with most saying they would ideally like to have two or three children (see Weston and Qu, p.10 of this edition on Family Matters). Yet some authors have argued that people want fewer children as they age (McDonald 1998). If this is the case, then today's young adults would hold lower family size aspirations than those originally held by today's older people; and as young adults mature, they too, will revise their aspirations downwards.

Goldstein, Lutz and Testa (2003) maintain that the fall in the total fertility rate itself results in a decline in family size ideals of future generations of young adults, although there is a considerable lag in this effect. Their analysis suggests that, while two children have long been seen as ideal in many European counties, in 2001, family size ideals were below this level for young women in Germany and Austria (averaging 1.7 children, while the total fertility rate has fallen to below 1.4).

If young adults also experience a downward revision in aspirations as they age, or if they under-achieve their aspirations (which inevitably occurs for some people who postpone starting a family), then the total fertility rate will fall further - a trend that will be accentuated over the years if declining fertility rates eventually result in lowered aspirations of future generations of young adults.

These issues are important because future trends in Australia's total fertility rate will be strongly affected by the proportions of women who have more than two children. McDonald (1998) estimated that the total fertility rate would fall to 1.4 if those who currently have more than two children stopped at two. Such a low level would not only increase the rate of population ageing, but also lead to a decline in the Australian-born population - a trend that would gain rapid momentum with time. Helping people to maintain and meet their original family size aspirations is clearly relevant to these issues.

How common is revision of aspirations from early adulthood to the late thirties? That is, to what extent does the similarity of family size aspirations across age groups observed in the Fertility Decision Making Project result from revision of aspirations for older people to approximate those of young adults, rather than from similar and entrenched aspirations across time? In the light of low fertility rates, little attention has been given to the possibility that some people may revise their aspirations upwards. How common is this process? And what are the reasons for any changes in aspirations?

Understanding the reasons for revised aspirations may contribute to the development of policy strategies that not only help people enjoy parenthood, but also help stem any further decline in the fertility rate. This, in turn, would prevent increases in the rate of population ageing and help Australia avoid the potential scenario of a spiralling decline in the Australian-born population.

In the Institute's Fertility Decision Making Project, respondents who were 22 years or older at the time of the interview in early 2004 were asked about the number of children they would ideally like to have, and the number they had wanted when they were 20 years old. If they indicated that their views now differed, they were also asked to explain the reasons underlying the discrepancy. Their answers were recorded verbatim.

This article first explores the apparent extent to which men's and women's views about having children and their ideal family size had changed since they were 20 years old, and the direction of any such change. The various patterns of reasons offered by respondents for revised preferences are then outlined.

Two sets of quantitative analyses were undertaken. First, respondents' current (2004) views about becoming parents were compared with their views at age 20. Second, for those who had wanted to be parents, the proportions who wanted fewer, more or the same number of children than they wanted at age 20, were examined. Trends for men and women across three age groups were derived: 25-29 years, 30-34 years, and 35-39 years. (See boxed inset for notes on the interpretation of trends.)

Interpreting the results

Throughout this article it is assumed that differences between the aspirations held at the time of the survey and those recalled for the early period reflect the overall level of change with no significant oscillation in the intervening period. This may not be correct.

Second, a higher proportion of men than women declined to indicate the number of children they wanted when they were 20 years old (9 per cent compared with 17 per cent). However, this "non-response rate" did not vary according to current age.

Finally, the wording of the questions tapping current and earlier preferences differed slightly. Respondents who indicated that they would like to have a first or additional child were asked: "Ideally, how many children would you like to have in total?" All respondents were later asked: "Looking back to when you were around 20, can you recall how many children you wanted?" Nevertheless, any ambiguity arising from this different wording in the two questions would not affect comparisons of trends across age groups or gender. Such comparisons form the focus of this article.

Views about becoming a parent

Not surprisingly, those in their thirties who wanted children at both times were more likely to be parents than those of the same age whose desire for children emerged some time after age 20 (men 61 per cent compared with 41 per cent; women 80 per cent compared with 69 per cent).

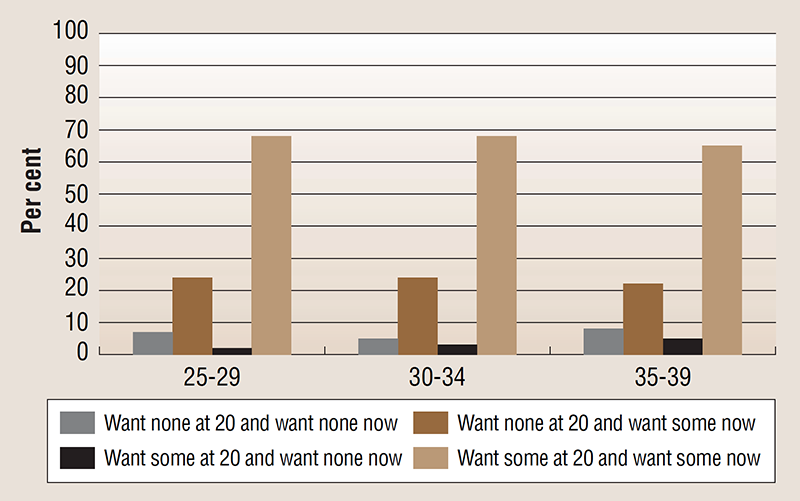

In total, around two-thirds of the men (67 per cent) and three-quarters of the women (77 per cent) indicated that they wanted children during both periods, while 23 per cent of men and 17 per cent of women said that, while they did not want children when they were 20 years old, they had changed their mind. Only 3 per cent of men and 2 per cent of women indicated that they wanted children at 20, but not currently, while 6 per cent of men and 5 per cent of women indicated that they wanted children neither at age 20 nor currently.

Thus, assuming that any oscillation of views during the interim period is uncommon and recollections of respondents are reasonably accurate, it appears that most men and women consistently wanted children. Figures 1a and 1b suggest that this picture applied to the three age groups. The proportions of men and women who indicated that they wanted children at age 20 and currently ranged from 65 per cent to 68 per cent for men, and from 76 per cent to 77 per cent for women. Less than 8 per cent in any age group indicated that they neither wanted children at age 20 nor currently. In fact, most men aged in their late thirties were parents (63 per cent) as were most women in their early and late thirties (70 per cent and 84 per cent respectively).

Figure 1a. Men's views about becoming parents: at age 20 and now (2004) by current age

Figure 1b. Women's views about becoming parents: at age 20 and now (2004) by current age

Across all age groups, those who reported a change in views were more likely to indicate a conversion from not wanting a child to wanting a child (a "positive conversion") rather than the reverse (a "negative conversion"). Positive conversions were indicated by 22 to 24 per cent of all men and by 15 to 18 per cent of all women. Negative conversions, on the other hand, were indicated by no more than 5 per cent of respondents in any group.

It thus seems reasonable to suggest that most respondents believed that they wanted to have children at least from early adulthood and continued to feel that way, with most of the others having decided, when older than 20 years, that they wanted children.

Views about family size

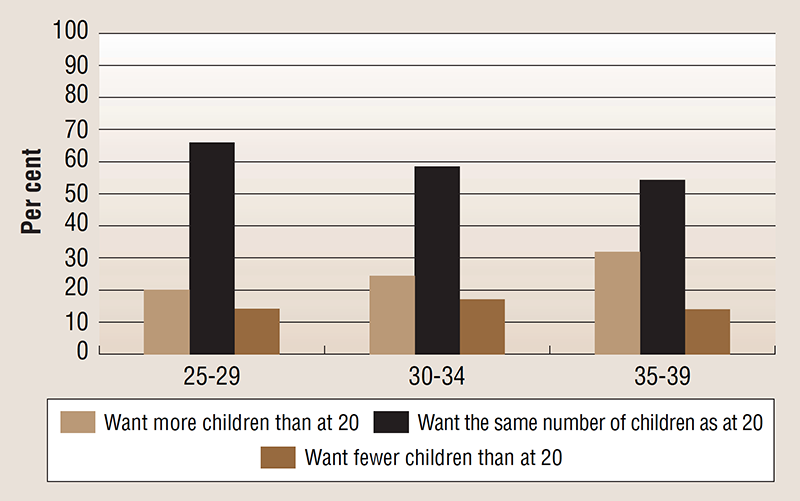

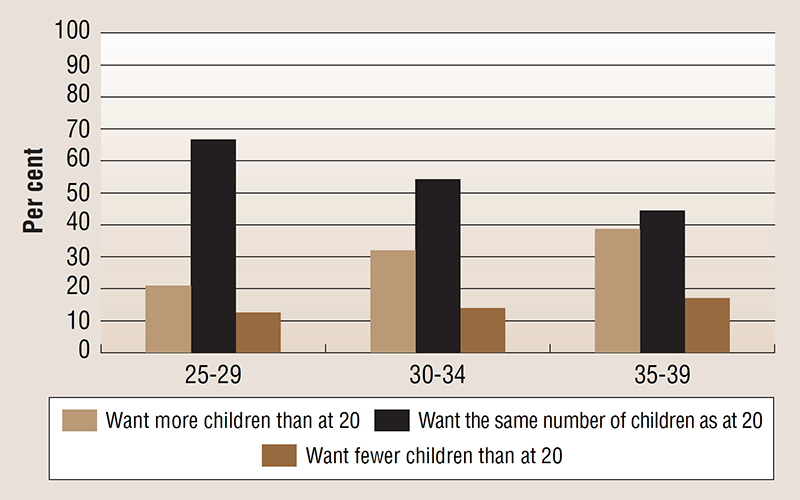

While any change in views about having a child at all tended to represent a switch from preferring childlessness to wanting to have children, among those who wanted children at age 20, family size preferences were more likely to be revised downwards than upwards - except for men in their twenties (Figures 2a and 2b). An upward revision was reported by 13 to 17 per cent of men and women in each age group.

The tendency to revise family size preferences downwards appeared to increase with increasing age (Figures 2a and 2b). For instance, a revision downwards was indicated by 20 per cent of men in their late twenties and by 32 per cent of men in their late thirties. For women, the proportions were 21 per cent and 39 per cent respectively. Nevertheless, with the exception of women in their late thirties, more than half the respondents indicated no change in desired family size.

Reasons for changes in views

Explanations for the fall in the total fertility rate are often sought through macro-level analysis of differences between countries in employment rates, couple formation trends, family-related and work-related government policies and so on (Castles 2002; McDonald 2000a, 2000b). Another important means of identifying reasons for the fertility rate decline is through an examination of ways in which parenting status and family size vary for different socio-demographic groups.

While both these approaches are very informative, much can be learned from the voices of those who speak from experience - the survey respondents themselves. This section provides examples of the reasons respondents gave for changing their aspirations about becoming parents or about family size since they were 20 years old.

Some of the reasons for wanting more children or fewer children than at age 20 covered the same general themes. People often gave more than one reason, as reflected in some of the quotations below.

Financial and work-related issues

Not surprisingly, financial and work-related issues were commonly offered as reasons for downward revision:

"Because of being more realistic. The cost of living now is not like before. What is the point of having more children if you won't be able to look after them? Because of financial pressure you will have to go back to work." (Woman aged 35, married)

"I just realized how hard and costly it is to cope these days." (Man aged 36, married)

"Probably because things have changed over the years - the cost of education and bringing up children - and because I don't want to go back to work and put them in day care." (Woman aged 33, married)

"Because of the value of money and because I want my kids to have private schooling." (Woman aged 27, married)

Nevertheless, a few respondents explained that they wanted more children than they originally wanted because their financial or work circumstances had improved:

"My husband earns enough money that we can afford more than two. They're lovely to have around. More than two would be nice." (Woman aged 34, married)

"Because I settled down and have a steady job." (Man aged 28, single)

Age issues

A great deal of attention in the literature is given to the fact that people are putting off having children until it is too late. This issue was often mentioned by those who had revised their aspirations downwards:

"We didn't have our first child until I was 29. I don't want to have children when I am over 35." (Woman aged 30, married)

At the same time, a number of people who had changed from not wanting children to wanting them referred to the fact that they had "grown up". But in the 1950s and 1960s people were having children in their early twenties - there was no time to reflect:

"I matured and realised there's more to it. I never associated children with such love and joy. I was more materialistic when I was younger." (Man aged 37, married)

Figure 2a. Men at age 20 who wanted to have a child: family size preferences then and now (2004) by current age

Figure 2b. Women at age 20 who wanted to have a child: family size preferences then and now (2004) by current age

"Maturing - your whole thought process changes, particularly after you turn 30. I ended up wanting a child." (Woman aged 37, married)

The combination of growing maturity and seeing friends and others have children sometimes generated a desire for children:

"If I were involved in a relationship, I think I would have liked to have a large family, but now I'm almost 40, time has kind of run out." (Woman aged 37,single)

"I wasn't thinking about children then. But now my friends are doing it; it's in my life; it is all around me. My desire, my urge, to have kids is now there." (Woman aged 27, married)

"I know people with families now. Being exposed to them has changed my views." (Man aged 30,single)

Partnering issues

Partnering issues covered having a partner, and the influence of a partner's views, and the quality of the relationship. Lack of a partner coupled with advancing age sometimes led people to decide they no longer wanted any children, or not as many as they wanted at age 20:

"If I were involved in a relationship, I think I would have liked to have a large family, but now I'm almost 40, time has kind of run out." (Woman aged 37,single)

"I did not feel that my relationship at the time would end. As I am getting older, I feel that I have less time in which to have kids and would only be able to fit in two maximum." (Woman aged 32, single)

On the other hand, some respondents decided they wanted to become parents or to have more children than they previously wanted upon entering into a rewarding relationship:

"Being happy in a relationship. I wanted to start a family with my partner and became maternal." (Woman aged 32, cohabiting)

"I am in a better relationship - our house is so full of love and is a better environment for raising children. It is a much more loving relationship than my previous relationship and I wanted more children with [current partner]." (Woman aged 26, married)

Some people's family size aspirations increased or decreased to take into account their partner's views:

"My husband didn't want any more than two. He was from a family of six and never got anything, so wanted to give his two everything." (Woman aged 34, married)

"Since meeting my partner my views have changed. He loves having a family of his own that he can care for and support, whereas I'm from a small family. All I had was my sister, so since meeting him, it's rubbed off on me a bit in wanting a family." (Woman aged 27, married)

Parenting experiences

Not surprisingly, difficult parenting experiences led to downward revisions; rewarding experiences had the reverse effect:

"Just the experience of having a child - I wasn't prepared for the amount of work that it was." (Woman aged 30, married, explaining why she wanted fewer now)

"I've actually had them. They're a lot of work." (Woman aged 26, married)

"Now I have been exposed to them I realise how much respect and love I have for them. Since I had one, it changed my world." (Man aged 24, cohabiting)

"I had not had kids when I was in my early twenties. Now that I've had two kids I know how much I enjoy having kids and would like to have more." (Woman aged 28, single)

Other reasons

Health and physical problems in having children sometimes led people to decide that they did not want any (more) children. Others who had revised their views downward explained this change of heart in terms of the problematic state of the world for raising children or over-population. On the other hand, upward revisions were sometimes explained in terms of a desire to have both a boy and a girl or to give a child sibling.

Summary and conclusions

While recollections may be coloured by current intervening experiences and changing priorities in other areas of life, they nonetheless represent important information about how people view the way their lives are unfolding.

Together, survey responses suggest that most men and women in each of the three age groups examined in the Fertility Decision Making Project wanted children both at age 20 and at the time of the survey (with nearly two-thirds of the men and more than 80 per cent of the women in their late thirties being parents at the time of the survey). Those who reported a change in views about having any children were more inclined to indicate a conversion from not wanting to wanting a child, rather than the reverse.

On the other hand, family size preferences among the majority who wanted children at age 20 years appeared to change considerably with age. Of those aged in their late thirties, around half the men and women reported such a change. Consistent with discussions in the literature, this change was more likely to be in a downward rather than upward direction - that is, most of these respondents indicated that at the time of the survey they wanted fewer children than they had previously wanted.

Reasons for respondents revising their family size aspirations downward and upward often related to the same broad themes, and in general were consistent with the literature concerning some of the broad social forces contributing to a decline in fertility. These included the financial costs of having children, job insecurity and the difficulties of combining work and family life (Castles 2002; McDonald 2000a, 2000b). Problems in these areas were seen as constraints that led to a downward revision, while a few respondents who revised their family size upward mentioned that they had experienced improved financial or work circumstances. But as noted by Weston in this edition of Family Matters (p.4), many of today's perceived "necessities" in life are linked with values. It is therefore not surprising that downward revisions sometimes involved considerations about private education for children.

Again, a commonly mentioned reason for the low fertility rate concerns the increased delays in achieving those milestones that precede having children, along with the difficulty in finding a partner and in maintaining a stable relationship. These issues were also mentioned by some respondents. Advancing age, lack of a partner and relationship breakdown led to revisions downward, while "growing up", finding a partner and feeling secure in this relationship were often mentioned as reasons for upward revision. Interestingly, while in the 1950s and 1960s, men and women tended to leave home at age 20 to 22 in order to marry and raise a family (McDonald 1995), the comments of many of these respondents who had "grown up" highlight the prolonging of adolescence these days.

For some people, difficulties they had experienced in parenting led them to want fewer children. For others, the sheer joy they encountered in becoming parents led them to want more children. This highlights the importance of effective strategies that help reduce the considerable stress experienced by some parents, not only to enable parenting to be an enjoyable experience, but also to remove a potential obstacle to having another child. Some respondents reported that they were surprised about how delightful the experience of parenting could be. This is not surprising given that families with problems are far more likely to attract attention than those without. Difficult children are also more likely to attract attention than children who are progressing well.

If Australia is to boost its fertility rate - or at least stem further falls - then the message that raising children has an intrinsic richness and is an enjoyable adventure in life needs to be conveyed widely. But to be effective, such a message must reflect reality. Couples need to have personal resources such as a secure income stream, a loving and stable relationship, and skills and confidence in parenting. They also require access to community resources, including family-friendly workplaces, and the confidence that they have a strong, continuing commitment from government and community that they are not alone in raising the next generation of citizens.

References

Brandtstädter, J. & Rothermund, K. (2002), "The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: A two-process framework", Developmental Review, vol. 22, pp. 117-150.

Castles, F.G. (2002), "Three facts about fertility: Cross-national lessons for the current debate", Family Matters, no. 63, pp. 22-27

Goldstein, J., Lutz, W. & Testa, M.R. (2003), The Emergence of Sub-Replacement Family Size Ideals in Europe. European Demographic Research Papers 2. Vienna Institute of Demography of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna.

McDonald, P. (1995), Families in Australia: A socio-demographic perspective, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne.

McDonald, P. (1998), "Contemporary fertility patterns in Australia: First data from the 1996 census", People and Place, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1-13.

McDonald, P. (2000a), "Low fertility in Australia: Evidence, causes and policy responses", People and Place, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 6-20.

McDonald, P. (2000b), "The new economy and its implications for Australia's demographic future", Paper presented to the 10th Biennial Conference of the Australian Population Association, 29 November.

Milsum, J.H. (1984), Health, stress and illness: A systems approach, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Lixia Qu is a Research Fellow and demographic trends analyst at the Australian Institute of Family Studies. Ruth Weston is a Principal Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies responsible for the Marriage and Family research program.

This article is adapted from Chapter 4 of a larger report by Ruth Weston, Lixia Qu, Robyn Parker and Michael Alexander, "It's not for lack of wanting kids": A report on the Fertility Decision Making Project, Prepared for the Office for Women, Australian Government Department of Family and Community Services, by the Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2004.