Family is for life

Connections between childhood family experiences and wellbeing in early adulthood

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

September 2010

Diana Smart

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

A large body of international research has shown that the experiences of childhood can exert an enduring influence on an individual's life. However, there is a dearth of recent Australian research demonstrating connections between childhood experiences within the family, and outcomes in adulthood. The current study provides prevalence figures for a range of childhood familial experiences (both positive and adverse), and examines the associations between these experiences and psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood. The sample comprised 1,000 participants of the Australian Temperament Project, a longitudinal study of children's development that commenced in 1983 and has collected 14 waves of data over the first 24 years of life. Key findings suggest that positive development (or 'doing well') in young adulthood relies on the active investment of caregivers? love, affection and encouragement during childhood, rather than simply the absence of adverse experiences. They also indicate that although young adult survivors of childhood maltreatment may be faring adequately in the social sphere, they are still much more likely than others to suffer from internalising problems such as depression and anxiety.

This article highlights the formative influence of familial childhood experiences on the lives of young adults. Using data from the Australian Temperament Project (ATP), links are explored between supportive parent-child relationships, adverse family experiences in childhood and psychosocial outcomes in early adulthood.

A large body of research has shown that the experiences of childhood can exert an enduring influence on an individual's life (e.g., Rutter, Kim-Cohen, & Maughan, 2006; Schilling, Aseltine Jr, & Gore, 2007). For better or worse, many people's most defining relationships and experiences occur within the context of their families. Positive family relationships can help children flourish, but adverse experiences can have a negative impact on children's wellbeing and subsequent development.

Negative or traumatic childhood experiences within the family are associated with an array of psychosocial problems in later life. For example, individuals who grew up in poverty or whose parents suffered from a mental illness or substance abuse problem are more likely than others to themselves experience physical health problems (e.g., cardiovascular disease), mental illness (e.g., depression) or substance abuse problems in adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998; Poulton, et al., 2002; Strom, 2003).

Similarly, adult survivors of child abuse and neglect are at an increased risk of a range of both physical health conditions (e.g., chronic pain, headaches, gynaecological problems) (Felitti et al., 1998; Sachs-Ericsson, Cromer, Hernandez, & Kendall-Tackett, 2009) and mental health disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, psychosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders) (Afifi, Boman, Fleisher, & Sareen, 2009; Chapman et al., 2004). They are also more likely than other individuals to engage in alcohol and substance abuse, as well as violent and criminal behaviours (Felitti et al., 1998; Gilbert et al., 2009). Perhaps unsurprisingly, children who are subjected to repeated incidents and/or multiple types of maltreatment over a prolonged period are at an even greater risk of experiencing these negative outcomes (Bromfield, Gillingham, & Higgins, 2007; Higgins & McCabe, 2000).

On the other hand, supportive childhood experiences within the family are related to positive adult outcomes. Individuals whose parents were encouraging and loving and provided appropriate boundaries tend to have higher levels of self-esteem, hope and subjective happiness than those whose parents were overly strict or permissive (Furnham & Cheng, 2000; Heaven & Ciarrochi, 2008; McCrae & Costa Jr, 1988). Similarly, secure attachment in childhood (i.e., a strong and loving bond between the caregiver and child) is associated with satisfying and secure personal relationships in adulthood (Feeney, 2008; Hazan & Shaver, 1987). Others have argued that the family is the most fundamental source of social capital, and that positive familial experiences and environments are associated with high levels of social competence, civic engagement, and trust and tolerance in social groups and institutions (Fukuyama, 1999; Putnam, 1995; Whitley & McKenzie, 2005).

Although there is considerable international research demonstrating associations between childhood experiences and outcomes in adulthood, there is little Australian research in this area. Each society has its own unique social, cultural, environmental and economic conditions. While international research can act as a guide for evidence-based policy and practice in Australia, its findings and conclusions need to be informed by research produced within an Australian social context.

The purpose of the current research therefore is to investigate connections between differing types of familial experiences during childhood and psychosocial outcomes in early adulthood. There has been considerable research on the risk factors and precursors of problem outcomes in early adulthood, but less attention has been given to the factors that promote optimal development - an absence of problems is by no means the same as "doing well". It is important to look at both problematic and positive outcomes when examining the long-term impact of family experiences on young people.

As in many other studies in this area, childhood family experiences were retrospectively reported in the current study. There has been debate about the accuracy of such reports, with memory loss and recall bias being commonly identified problems (Becket, DaVanzo, Sastry, Panis, & Peterson, 2001). However, previous research with members of the current study found high concordance between retrospective reports and other sources of data (e.g., between self-reports of contact with the police for offending and official police records; Smart et al., 2005), suggesting retrospective reports can provide useful and reliable information.

In the current study, measures of long-term health problems, depression, anxiety, antisocial behaviour and substance use were used as indicators of problem outcomes in early adulthood. Elements of positive development previously identified among young Australian adults (Hawkins, Letcher, Sanson, Smart, & Toumbourou, 2009) were used as indicators of positive functioning; namely social competence (empathy, responsibility and self-control), trusting and tolerant attitudes towards others, trusting and tolerant attitudes towards societal institutions (e.g., police, governments), active engagement in civic life (e.g., donating time to charity organisations), as well as personal strengths (e.g., autonomy, planfulness, life satisfaction).

Two questions were addressed:

- How common are supportive and adverse familial childhood experiences among a community sample of young Australians?

- Are supportive parent-child relationships and adverse family experiences during childhood related to young people's wellbeing in early adulthood?

The study

The data analysed in this study come from the Australian Temperament Project, a longitudinal community study that has followed the development of a large group of Victorians from infancy onwards (for more details, visit the study website: <www.melbournechildrens.com/atp/>).

The study commenced in 1983 with the recruitment of over 2,400 infants (aged 4-8 months) and their parents, from urban and rural areas in the state of Victoria. The sample was representative of the Victorian state population at that time. Fourteen waves of data have been collected by mail surveys to 2006, with a 15th collection planned to take place in 2010. Parents, teachers, maternal and child health nurses, and the children/young people themselves have participated.

Approximately two-thirds of the sample are still enrolled in the study after 27 years. Attrition over the course of the study has resulted in a slight under-representation of families from lower socio-demographic backgrounds or with a non-Australian born parent. However, there are no significant differences between the retained and no-longer-participating samples in terms of the children's temperament style or behaviour problems in infancy. Thus, the findings reported here are likely to slightly underestimate the effects of growing up in an immigrant family or a family with low socio-economic status, but remain representative of the diversity of child temperamental and behavioural characteristics in the general population.

A wide range of aspects of life has been studied, including young people's temperament, health, social skills, behavioural and emotional problems, risk-taking behaviours, educational and occupational progress, and peer and family relationships, as well as family functioning, parenting practices and socio-demographic background.

During the most recent survey - conducted in 2006-07 when study members were 23-24 years of age - young people were asked to reflect on their family experiences, both positive and negative, prior to age 18. The findings presented in this paper are based on a sample of 1,000 study members (390 males, 610 females).

Measures

Table 1 presents a summary of the childhood and early adulthood indicators used in this paper.

| Childhood family experiences | Positive psychosocial outcomes | Problem psychosocial outcomes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Childhood family experiences

The questions used to measure young peoples' family experiences while growing up are shown in Table 2. Findings are reported for both the individual items and for composite scores formed from these items. Four main indicators of childhood family experiences were used: supportive parent-child relationships, parental mental health/substance use problems, poverty, and child maltreatment.

| Supportive childhood family experiences | When you were growing up:

|

|---|---|

| Adverse childhood family experiences | When you were growing up:

|

Note: Questions 1-5, 7 and 10-12 were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very true, 5 = not at all true). Questions 6 and 8-9 were measured using a yes/no format.

The "supportive parent-child relationships" measure was created by computing the average of items 1, 4 and 5 in Table 2 (close relationships with parents, parents were loving and affectionate, parents encouraged child to be the best he/she could). Two groups were formed on the basis of their scores on this measure:

- "very supportive parent-child relationship" group ( n = 786, 79% of sample) - rated all three aspects of supportive parent-child relationships as being "very" or "somewhat" true of their childhood experiences; and

- "less supportive parent-child relationship" group ( n = 205, 21% of sample)1 - were less positive in their perceptions of their relationships with parents. Nevertheless, they did not necessarily report that they had a negative relationship with their parent(s); they were simply less emphatically positive than those in the very supportive parenting group.

Differing types of adverse family experiences are listed as items 6-12 in Table 2. "Parental mental health/substance use problems" or "poverty" were deemed to be present if study members answered yes to items 6 or 7 respectively. Items 8-12 reflect differing forms of maltreatment. A composite measure of maltreatment was developed by summing the differing types of abuse and neglect reported (i.e., physical abuse, intra-familial sexual abuse, emotional maltreatment, neglect, witnessing family violence). Three groups were formed:

- "no maltreatment" group ( n = 768, 77% of the sample) - did not report any experience of child maltreatment;

- "single maltreatment" group ( n = 153, 15% of the sample) - reported one form of maltreatment; and

- "multiple maltreatment" group ( n = 79, 8% of the sample) - reported two or more forms of maltreatment.

Psychosocial outcomes at 23-24 years

The psychosocial outcome measures at 23-24 years are shown in Table 3. Five positive and six problem outcomes were employed. All outcomes were composites of items, with the exception of long-term health problems and high-risk binge drinking, which were both single items.

| Positive psychosocial outcomes |

|

|---|---|

| Problem psychosocial outcomes |

|

Positive psychosocial outcomes were based on Hawkins et al. (2009), who identified five core characteristics of positive development among ATP study members at 19-20 years. The positive psychosocial outcomes at 23-24 years comprise items 1-5 in Table 3: civic action and engagement, personal strengths, social competence, trust and tolerance of others, and trust and tolerance of organisations. For each outcome, three groups were formed to denote those who showed high, medium and low levels of the outcome. Those with scores in the lowest 25% of the ATP sample distribution on a particular characteristic comprised the "low" group, the 25% of study members with the highest scores formed the "high" group, and the remaining 50% of study members were placed in the "medium" group. It should be noted that those in the high groups were not necessarily very high on the characteristic in question, but rather they were high in comparison to their ATP counterparts.

For the six problem psychosocial outcomes (i.e., long-term health problem, depression, anxiety, high-risk binge drinking, illicit drug use, antisocial behaviour), study members were divided into dichotomous yes/no groups according to previously established criteria. For example, high depression and anxiety were identified using the norms provided for the scale; binge drinking was measured using the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia's definition of short-term high-risk drinking; and the cut-off for antisocial behaviour paralleled the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-R diagnostic criteria (engagement in three or more differing types of antisocial acts in the previous 12 months).

Findings

In this study, all childhood family experiences were retrospectively reported.

Question 1: How common are supportive or adverse familial childhood experiences among a community sample of young Australians?

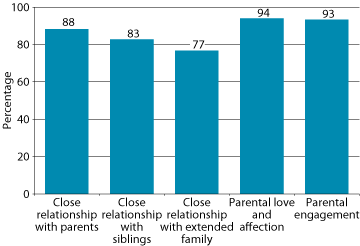

The vast majority of young people reported supportive family experiences while growing up (see Figure 1). For example, 94% indicated that their parents had shown love and affection towards them, 93% believed their parents encouraged them to achieve their best, and 88% felt they had a close relationship with their parents. A smaller but sizable proportion (77%) reported that their family often spent time with their grandparents, aunties, uncles or cousins.

Figure 1: Reports of supportive familial experiences while growing up, 23-24 year olds

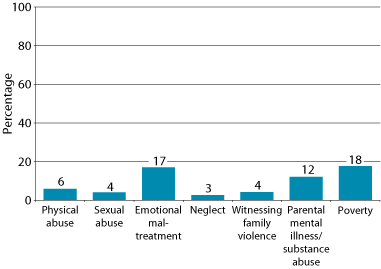

The percentage of young people who reported adverse childhood experiences is shown in Figure 2. Poverty was reported by 18% of study members. Seven per cent of all study members indicated that their father had suffered from a mental illness or substance abuse problem, 4% their mother, and 1% both their parents (a total of 12% of all respondents). Emotional maltreatment was reported by 17%, making it the most common form of maltreatment. Neglect was indicated by 3%, making it the least commonly reported form of child maltreatment. In total, almost one-quarter (23%) of study members reported the experience of one or more forms of maltreatment.

Figure 2: Reports of adverse familial experiences while growing up, 23-24 year olds

Question 2: Are supportive parent-child relationships and adverse family experiences during childhood related to young people's wellbeing in early adulthood?

Supportive parent-child childhood relationships

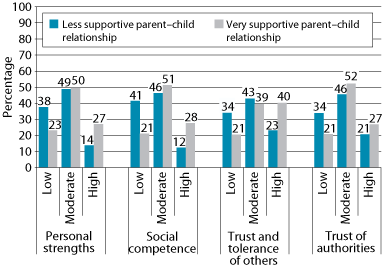

Supportive parent-child childhood relationships were significantly associated with higher levels of almost all positive development outcomes at 23-24 years of age: personal strengths, social competence, trust and tolerance of others, and trust in authorities. However, they were not related to civic action and engagement.

Figure 3 shows the percentage of the very and less supportive parent-child relationship groups that had low, moderate or high levels on the outcomes for which significant differences were found. As the figure shows, those with less supportive parent-child relationships more often showed low levels of positive development, while those with very supportive relationships more frequently showed high levels. For example, looking at personal strengths on the left side of the figure, 38% of the less supportive group showed low levels compared with 23% of the very supportive group; similar proportions of the two groups showed moderate levels (49% and 50%); and only 14% of the less supportive group showed high personal strengths, compared with 27% of the very supportive group.

Figure 3: Parent-child relationship groups, by level of positive development, 23-24 year olds

Turning now to connections with problem outcomes in early adulthood, those in the very supportive parent-child relationships group were significantly less likely than those in the less supportive relationship group to have recently suffered depression (12% vs 30%) or anxiety (14% vs 25%). There were no significant connections between supportive parent-child relationships and long-term health problems, illicit drug use, binge drinking or antisocial behaviour in early adulthood.

Parental mental illness/substance use problems during childhood

Looking first at links with positive outcomes in early adulthood, young people who indicated that their parents had a mental illness or substance use problem while the young people were growing up were less trusting of authorities than their peers, being particularly less likely to report high levels of trust (15%, compared with 27% of those whose parents did not have a mental health or substance use problem). There were no significant associations with any of the other positive development measures (i.e., civic action and engagement, personal strengths, social competence, and trust and tolerance of others).

In terms of problem outcomes at 23-24 years, reports of parental mental illness/substance use problems were significantly associated with higher rates of long-term health problems among young people (32% vs 20%). However, they were not related to any other problem outcomes (i.e., depression, anxiety, illicit drug use, binge drinking or antisocial behaviour).

Childhood poverty

Young people whose families experienced poverty when they were growing up tended to be less trusting and tolerant of others at 23-24 years, being especially likely to express low trust and tolerance (31% vs 22%). They were also less trusting of authorities, more frequently expressing low levels of trust (33% vs 21%) and less often having high trust in authorities (17% vs 28%). There were no significant connections between childhood poverty and the other aspects of positive development: civic action and engagement, personal strengths and social competence.

Looking next at problematic outcomes at 23-24 years, study members with a background of poverty were significantly more likely than their peers to suffer depression (22% vs 15%) or anxiety (22% vs 15%), but less likely to engage in high-risk binge drinking (22% vs 29%). There were no significant connections between childhood poverty and the other problem outcomes (i.e., health problems, illicit drug use and antisocial behaviour).

Childhood maltreatment

Maltreatment during childhood was associated with significantly lower levels of personal strengths in early adulthood. Specifically, those in the multiple maltreatment group were less likely to report high levels of personal strengths (17%) than those in the single (19%) or no maltreatment (26%) groups. Nevertheless, child maltreatment was not significantly related to any of the other positive development outcomes (i.e., civic action and engagement, social competence, trust and tolerance of others, and trust in authorities).

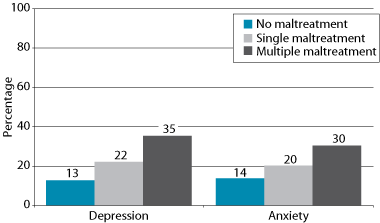

As can be seen in Figure 4, significantly more members of the multiple maltreatment group (35%) experienced high levels of depression than those in the single (22%) and no maltreatment (13%) groups. Similar significant differences were also found between the single and no maltreatment groups. Additionally, those in the multiple maltreatment group were significantly more likely than those in the other two groups to report high levels of anxiety. There were no associations between child maltreatment and long-term health problems, illicit drug use, binge drinking, or antisocial behaviour in early adulthood.

Figure 4: Childhood maltreatment groups, by psychosocial adjustment problems, 23-24 year olds

Childhood experiences and accumulated problems in early adulthood

As well as exploring whether adverse childhood family experiences conveyed risk for specific types of problems in early adulthood, an investigation was made into whether these types of experiences were associated with a greater overall burden of difficulties. An index of total number of problems was created by summing the number of problems present, using the indicators: depression, anxiety, illicit drug use, long-term health problem, high-risk binge drinking, and antisocial behaviour. Scores could range from zero (no problems experienced) to six (all types of problems experienced). Across the ATP sample, a total of 398 23-24 year olds (40%) had zero problems, 302 (30%) had one, 181 (18%) had two, and 119 (12%) had three or more problems.

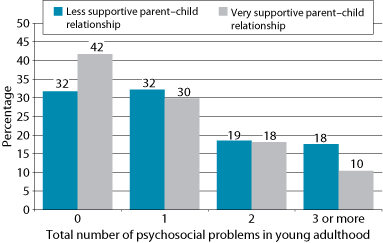

Figure 5 shows that 42% of young people with very supportive parent-child relationships in childhood did not experience any problems in early adulthood, compared with 32% of those with less supportive relationships. Conversely, 37% of those with less supportive relationships experienced two or more problems compared with 28% of those with very supportive relationships.

Figure 5: Parent-child relationship groups, by number of psychosocial problems in young adulthood

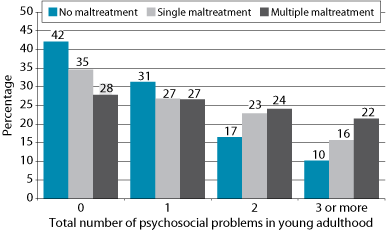

On the other hand, those whose parents had a mental illness or substance use problem while they were growing up were significantly more likely to experience multiple problems in early adulthood, especially those who had three or more problems (20% vs 11%). The experience of child maltreatment was also related to a higher cumulation of problems. Figure 6 shows that the incidence of three or more problems was significantly greater in the multiple maltreatment group (22%) than the single (16%) or no maltreatment (10%) groups. Only childhood poverty was not significantly related to the occurrence of multiple problems in early adulthood.

Figure 6: Maltreatment groups, by number of problems in young adulthood

Childhood experiences and outcomes in early adulthood: Summary

A summary of connections between childhood experiences and psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood is presented in Table 4. Overall, very supportive parent-child relationships were consistently related to positive outcomes (the exception being civic action and engagement), while the three types of adverse family experiences were rarely related to positive outcomes (although individuals who experienced poverty or parental mental health/substance use problems tended to be less trusting than other young people).

| Psychosocial outcomes | Childhood experiences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supportive parent-child relationships | Maltreatment | Parental mental illness/ substance use | Poverty | ||

| Positive | Civic action and engagement | ||||

| Personal strengths | + | - | |||

| Social competence | + | ||||

| Trust and tolerance of others | + | - | |||

| Trust of authorities | + | - | - | ||

| Problem | Long-term health problem | + | |||

| Depression | - | + | + | ||

| Anxiety | - | + | + | ||

| Illicit drug use | |||||

| Binge drinking | - | ||||

| Anti-social behaviour | |||||

| Total number of problems | - | + | + | ||

Note: "+" = positive relationship, p < .05; "-" = negative relationship, p < .05.

Less supportive parent-child relationships, poverty and maltreatment in childhood were significantly associated with depression and anxiety in early adulthood. There were also some specific connections among 23-24 year olds between: (a) poverty and lower rates of binge drinking, and (b) parental mental health/substance use problems and the presence of long-term health problems. Further, supportive childhood experiences were related to a lower accumulation of problems in early adulthood, while parental mental health/substance use problems and maltreatment were associated with a greater multiplicity of problems. However, childhood family experiences were not related to illicit drug use, antisocial behaviour or civic action and engagement in early adulthood.

Discussion

This paper sought to investigate two issues: (a) rates of supportive and adverse familial childhood experiences among a community sample of young Australians, and (b) whether supportive parent-child relationships and adverse family experiences during childhood were related to young people's wellbeing in early adulthood.

The first point to note is the very large number of young people who felt they had been highly supported and loved by their parents while they were growing up. Close to 80% answered affirmatively to all three items (they had a close relationship with their parents, their parents were loving and encouraging towards them, their parents encouraged them to be the best they could), and rates of agreement on the individual items ranged from 88% to 94%.

On the other hand, quite a number of young people encountered adverse family experiences while growing up. Rates ranged from 12% whose parents suffered from a mental illness or a substance abuse problem, to 23% who experienced child abuse or neglect. It is noteworthy, and perhaps unexpected, that of the three types of adverse family experiences examined, the most common was maltreatment, pointing to the pervasiveness of this issue. These findings add to scarce Australian data on the occurrence of these adversities, and are especially important as they are derived from a community, rather than a clinical, sample.

When considering the proportion of study members who felt their parents had greatly loved and supported them, and the percentage who reported adverse family experiences, it is clear that many vulnerable families were able to provide a loving and secure environment for their children in the face of difficulties. These findings are a reminder of the capacity for resilience among families and children.

The second point to note is the salience of childhood family experiences for wellbeing and adjustment in early adulthood. Supportive parent-child relationships were related to valued positive qualities, such as planfulness, independence, social skills, and trusting and tolerant attitudes. These findings are in keeping with other research from the fields of positive psychology (Furnham & Cheng, 2000; Heaven & Ciarrochi, 2008; McCrae & Costa Jr, 1988) and social capital (Fukuyama, 1999; Putnam, 1995; Whitley & McKenzie, 2005). Further, those with very supportive parent-child relationships were less likely to suffer depression or anxiety. Overall, these findings suggest that having close, loving and encouraging childhood relationships with parents lays a strong foundation for thriving in young adulthood and may also buffer young people from mental health problems.

Noteworthy also were the connections between adverse childhood family experiences and lower wellbeing in early adulthood. Consistent with international research (Felitti et al., 1998; Poulton et al., 2002; Strom, 2003), parental mental illness and substance abuse were associated with long-term health problems, while both maltreatment and poverty were associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety. The single, somewhat surprising exception was the lower likelihood of binge drinking among those whose families had been financially impoverished. Nevertheless, it is also important to note that while adverse family experiences were linked to considerably higher rates of problems in early adulthood, the majority of those who encountered these adversities did not show high levels of problems in the areas examined. For example, while a comparatively high 35% of those in the multiple maltreatment group reported recent depression, 65% of the same group had not recently experienced depression.

There were interesting disparities in the connections between differing types of adverse family experiences and positive functioning. Child maltreatment was related to lower levels of personal strengths, but was not associated with lower levels of civic action and engagement, social competence, trust and tolerance of others, and trust in authorities. These findings suggest that individuals in this study who experienced child maltreatment were not impaired in their ability to contribute to, relate appropriately to, or function effectively in the social sphere. Rather, survivors of maltreatment were more likely to show difficulties in personal functioning (personal strengths, reflecting life acceptance, autonomy, identity clarity and planfulness). Similarly, and in keeping with the findings of other studies (e.g., Afifi et al., 2009; Chapman et al., 2004; Higgins & McCabe, 2000), they were more likely to suffer internalised psychological adjustment problems such as depression and anxiety.

In contrast, parental mental illness/substance use problems and family poverty were linked to lower levels of trust among young people, but not lower levels of personal strengths. This may to some extent reflect the more distal effect of family problems such as poverty or parental psychosocial problems, compared with behaviours that more directly affect children, such as abuse or neglect, and which may impede the development of an individual's personal capacities.

The findings also suggest that very positive parent-child relationships are related to, but not on a continuum with, adverse family experiences such as maltreatment. This is demonstrated by the lack of consistency in the connections found, with highly supportive parent-child relationships mainly associated with positive outcomes, and adverse family experiences with problematic ones. It is perhaps more accurate to say that the opposite of maltreatment, for example, is the absence of maltreatment, and that positive parent-child relationships exist on a similar but different continuum.

Not all outcomes examined were related to childhood family experiences, with no associations found between childhood family experiences and civic action and engagement, antisocial behaviour and illicit drug use at 23-24 years. It is possible that the low rate of antisocial behaviour among ATP study members at this age (7%) may have led to insufficient statistical power to detect relationships. This low rate is consistent with other research showing that antisocial behaviour typically peaks in mid-adolescence and steadily declines thereafter in the general population (Rutter, Giller, & Hagell, 1998). Similarly, rates of civic action and engagement were very low among ATP study members, resulting in little differentiation between the low, moderate and high civic action and engagement groups. The finding that most young adults in contemporary Australia are not actively engaged in civic life is consistent with both national and international social research (Hawkins et al., 2009; Print, 2007; Putnam, 1995). Reasons for the lack of associations with illicit drug use are less obvious.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study has a number of strengths. Firstly, in contrast to many similar studies that use self-selected or clinical samples, the findings of the current study are based on a relatively large community sample, which helps to decrease the biases that can arise from the former types of sampling. A further strength is that this a longstanding study in which a strong history of trust has developed with study members. Such trust is particularly important when respondents are asked to disclose very sensitive information, such as whether or not they experienced child maltreatment. A third major strength is the breadth of child, parent and family characteristics measured, allowing a wide range of influences and outcomes to be examined, and a cumulative index of problems to be developed.

However, the research also has several limitations. Like many longitudinal studies, sample attrition over the years has resulted in a slight under-representation of families with low socio-economic status. This is likely to have led to conservative estimates of the occurrence of adverse childhood experiences, especially as these are known to be higher among low socio-economic status groups. Secondly, the measures of some childhood experiences were not as detailed as in other studies due to the fact that the ATP is a life-course study, collecting information on a wide range of aspects of child and youth development. Other more narrowly focused studies are able to include more in-depth measures than those used here. Nevertheless, the rates of reported maltreatment, for example, accord well with the rates of other studies (Price-Robertson, Bromfield, & Vassallo, 2010). Finally, similar to many other studies in this area, childhood family experiences were retrospectively reported, which can lead to problems such as recall bias. However, there is encouraging evidence from within the study and elsewhere (e.g., Smart et al., 2005) to suggest that retrospective reports can be reliable and valid.

Key messages and implications

What do these findings mean? What practical implications do they have? Firstly, the findings suggest that positive development (or "doing well") in young adulthood relies on the active investment of the caregiver's love, affection and encouragement during childhood, rather than simply the absence of adverse experiences. This points to the importance of high-quality parenting, as distinct from "good enough" parenting. This has implications for the child and family welfare sector; it signals the need for services that focus on strengthening protective factors (such as positive relationships with caregivers) rather than solely on minimising risk factors (such as child maltreatment). It supports the use of evidence-based parenting programs, such as "The Incredible Years" and "Parenting Wisely", that attend to caregiver behaviours designed to enhance caregiver-child relationships.

Secondly, these findings indicate that although young adult survivors of childhood maltreatment may be faring adequately in the social sphere, they are still much more likely than others to suffer from internalising problems such as depression and anxiety. This has important implications for practitioners working within the field of mental health. It suggests that levels of social functioning cannot always be used as a proxy for overall psychosocial health. There is a need for mental health practitioners to be aware of and to address mental health issues in survivors of traumatic childhood experiences, even if they appear to be doing well socially.

Finally, the results of the current research support the use of positive development measures in future research. They indicate that positive development is not simply the opposite of problematic development, and by measuring both types of outcomes a more nuanced picture of psychosocial development can be obtained. Future research could build on the current findings by identifying the ways in which positive and adverse childhood experiences interact to influence adult behaviour; for example, whether positive parent-child relationships mediate the long-term outcomes associated with child maltreatment.

Endnotes

1 Note that the number of members of the two "supportive parent-child relationships" groups (n = 991) was not equal to the number of participants in the study (n = 1,000) because nine participants were missing relevant data from their questionnaires.

References

- Afifi, T. O., Boman, J., Fleisher, W., & Sareen, J. (2009). The relationship between child abuse, parental divorce, and lifetime mental disorders and suicidality in a nationally representative adult sample. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33(3), 139-147.

- Beckett, M., DaVanzo, J., Sastry, N., Panis, C., & Peterson, C. (2001). The quality of retrospective data: An examination of long-term recall in a developing country. Journal of Human Resources, 36(3), 593-625.

- Bromfield, L. M., Gillingham, P., & Higgins, D. J. (2007). Cumulative harm and chronic child maltreatment. Developing Practice, 19, 34-42.

- Chapman, D. P., Whitfield, C. L., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., Edwards, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 217-225.

- Chassin, L., Pitts, S. C., & DeLucia, C. (1999). The relation of adolescent substance use to young adult autonomy, positive activity involvement, and perceived competence. Development and Psychopathology, 11(4), 915-932.

- Elliott, D. S., & Ageton, S. S. (1980). Reconciling race and class differences in self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 45, 95-110.

- Feeney, J. A. (2008). Adult romantic attachment: Developments in the study of couple relationships. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd Ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

- Flanagan, T. J., & Longmire, D. R. (1995). National opinion survey of crime and justice. Huntsville, TX: Sam Houston State University, Criminal Justice Centre.

- Fukuyama, F. (1999). The great disruption: Human nature and the reconstitution of social order. New York: Free Press.

- Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2000). Perceived parental behaviour, self-esteem and happiness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 35(10), 463-470.

- Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373(9657), 68-81.

- Hawkins, M. T., Letcher, P., Sanson, A., Smart, D., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2009). Positive development in emerging adulthood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 61(2), 89-99.

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511-524.

- Heaven, P., & Ciarrochi, J. (2008). Parental styles, gender and the development of hope and self-esteem. European Journal of Personality, 22(8), 707-724.

- Higgins, D. J., & McCabe, M. P. (2000). Multi-type maltreatment and the long-term adjustment of adults. Child Abuse Review, 9(1), 6-18.

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335-343.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1988). Recalled parent-child relations and adult personality. Journal of Personality, 56(2), 417-434.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2001). Australian alcohol guidelines: Health risks and benefits. Canberra: NHMRC.

- Poulton, R., Caspi, A., Milne, B. J., Thomson, W. M., Taylor, A., Sears, M. R., et al. (2002). Association between children's experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: A life-course study. The Lancet, 360(9346), 1640-1645.

- Price-Robertson, R., Bromfield, L., & Vassallo, S. (2010). The prevalence of child abuse and neglect (Resource Sheet). Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse.

- Print, M. (2007). Citizenship education and youth participation in democracy. British Journal of Educational Studies, 55(3), 325-345.

- Putnam, R. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65-78.

- Rosenthal, D. A., Gurney, R. M., & Moore, S. M. (1981). From trust to intimacy: A new inventory for examining Erikson's stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10(6), 525-537.

- Rutter, M., Giller, H., & Hagell, A. (1998). Antisocial behaviour by young people. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Rutter, M., Kim-Cohen, J., & Maughan, B. (2006). Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 47(3-4), 276-295.

- Sachs-Ericsson, N., Cromer, K., Hernandez, A., & Kendall-Tackett, K. (2009). A review of childhood abuse, health, and pain-related problems: the role of psychiatric disorders and current life stress. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 10(2), 170-188.

- Schilling, E. A., Aseltine Jr, R. H., & Gore, S. (2007). Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: A longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health, 7(30).

- Smart, D., Richardson, N., Sanson, A., Dussuyer, I., Marshall, B., Toumbourou, J. W., et al. (2005). Patterns and precursors of adolescent antisocial behaviour: Outcomes and connections. Third report. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria.

- Smart, D., & Sanson, A. (2003). Social competence in young adulthood, its nature and antecedents. Family Matters, 64, 4-9.

- Stone, W. (2001). Measuring social capital: Towards a theoretically informed measurement framework for researching social capital in family and community life (Research Paper No. 24). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Stone, W., & Hughes, J. (2002). Social capital: Empirical meaning and measurement validity (Research Paper No. 27). Melbourne: Australia: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Strom, S. (2003). Unemployment and families: A review of research. Social Service Review, 77(3), 399-430.

- Whitley, R., & McKenzie, K. (2005). Social capital and psychiatry: Review of the literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 13(2), 71-84.

Price-Robertson, R., Smart, D., & Bromfield, L. (2010). Family is for life: Connections between childhood family experiences and wellbeing in early adulthood. Family Matters, 85, 7-17.