The AIFS evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms

A summary

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

March 2011

Rae Kaspiew, Kelly Hand, Lixia Qu

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

In 2006, the Australian Government, through the Attorney-General's Department (AGD) and the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), commissioned the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) to undertake an evaluation of the impact of the 2006 changes to the family law system: Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms (Kaspiew et al., 2009) (the Evaluation). This article provides a summary of the key findings of the Evaluation.

In 2006, a series of changes to the family law system were introduced. These included changes to the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) 1 and increased funding for new and expanded family relationships services, including the establishment of 65 Family Relationship Centres (FRCs) and a national advice line. The aim of the reforms was to bring about "generational change in family law" and a "cultural shift" in the management of separation, "away from litigation and towards cooperative parenting".2

The 2006 reforms were partly shaped by the recognition that although the focus must always be on the best interests of the child, many disputes over children following separation are driven by relationship problems rather than legal ones. These disputes are often better suited to community-based interventions that focus on how unresolved relationship issues affect children and assist in reaching parenting agreements that meet the needs of children.

The changes to the family law system followed an inquiry by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Constitutional Affairs (2003), which recommended changes to the family relationship services system and the legislation. The committee's report, Every Picture Tells a Story, made recommendations that aimed to make the family law system "fairer and better for children". The 2006 changes reflected some, but not all, of the recommended changes.

The policy objectives of the 2006 changes to the family law system were to:

- help to build strong healthy relationships and prevent separation;

- encourage greater involvement by both parents in their children's lives after separation, and also protect children from violence and abuse;

- help separated parents agree on what is best for their children (rather than litigating), through the provision of useful information and advice, and effective dispute resolution services; and

- establish a highly visible entry point that operates as a doorway to other services and helps families to access these other services.3

The policy objectives outlined above encompassed a range of more specific goals. A set of indicators of the success or otherwise of the reforms in achieving these objectives was developed. These were translated into the following evaluation questions:

- To what extent are the new and expanded relationship services meeting the needs of families?

- What help-seeking patterns are apparent among families seeking relationship support?

- How effective are the services in meeting the needs of their clients, from the perspective of staff and clients?

- To what extent does family dispute resolution (FDR) assist parents to manage disputes over parenting arrangements?

- How are parents exercising parental responsibility, including complying with obligations of financial support?

- What arrangements are being made for children in separated families to spend time with each parent? Is there any evidence of change in this regard?

- What arrangements are being made for children in separated families to spend time with grandparents? Is there any evidence of change in this regard?

- To what extent are issues relating to family violence and child abuse taken into account in making arrangements regarding parenting responsibility and care time?

- To what extent are children's needs and interests being taken into account when these parenting arrangements are being made?

- How are the reforms introduced by the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 ( SPR Act 2006) working in practice?

- Have the reforms had any unintended consequences - positive or negative?

The AIFS Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms was based on an extensive research program and provides a comprehensive evidence base on the operation of the family law system. The Evaluation included three main projects: the Legislation and Courts Project, the Service Provision Project and the Families Project. Each of these projects comprised a number of sub-studies, with 17 separate studies contributing to the Evaluation overall (see the text box at top right and Appendix for further information). The research design focused on examining the extent to which key aspects of the objectives underpinning the reforms had been achieved. The Evaluation involved the collection of data from 28,000 people involved in the family law system, including parents, grandparents, family relationship services staff, clients of family relationship services, lawyers, court professionals and judicial officers. It also involved the analysis of administrative data and court files. This article outlines the key research questions and findings from the Evaluation - references in parentheses throughout are to tables, figures and sections in the full Evaluation report. The full Evaluation report (Kaspiew et al., 2009) is available from the AIFS website <www.aifs.gov.au>.

A point that transcends the specific evaluation questions and has implications for the findings across all of the evaluation questions arises from the new empirical evidence from the Evaluation about the characteristics of separated families, particularly those who access services across the system. A significant proportion of families who actively engage with the family law system have complex needs, involving issues such as family violence, child abuse, mental health problems and substance abuse. For example, 26% of mothers and 18% of fathers reported experiencing physical hurt prior to separation, and 39% of mothers and 47% of fathers reported experiencing emotional abuse before, during and after separation (LSSF W1 2008; Table 2.2). Families with complex needs are the predominant clients both of post-separation services and the legal sector; however, there is also a proportion of families who do not engage with the system to any significant extent. While some of these families appear not to be characterised by any significant complexity in terms of family violence, mental health issues or substance abuse issues, there is a sub-group of non-users of the system for whom these issues are relevant.

Key studies referred to in this article

Legislation and Courts Project (LCP; see also Appendix)

Qualitative Study of Legal System Professionals 2008 (QSLSP 2008)

Family Lawyers Survey 2006 and 2008 (FLS 2006 and FLS 2008)

Quantitative Study of Family Court of Australia, Federal Magistrates Court and Family Court of Western Australia Files 2009 (QSCF 2009)

Service Provision Project (SPP; see also Appendix)

Qualitative Study of Family Relationship Services Program (FRSP) Staff 2008-09

Online Survey of FRSP Staff 2009

Survey of FRSP Clients 2009 (Survey of FRSP Clients 2009)

Families Project (see also Appendix)

General Population of Parents Survey 2006 (GPPS 2006)

General Population of Parents Survey 2009 (GPPS 2009)

Family Pathways: The Longitudinal Study of Separated Families (LSSF W1 2008)

Family Pathways: Looking Back Survey (LBS 2009)

Family Pathways: The Grandparents in Separated Families Study 2009 (GSFS 2009)

Evaluation question 1: To what extent are the new and expanded relationship services meeting the needs of families?

a. What help-seeking patterns are apparent among families seeking relationship support?

b. How effective are the services in meeting the needs of their clients, from the perspective of staff and clients?

There is evidence of fewer post-separation disputes being responded to primarily via the use of legal services and more being responded to primarily via the use of family relationship services. This suggests a cultural shift whereby a greater proportion of post-separation disputes over children are being seen and responded to primarily in relationship terms.

About half of the parents in non-separated families who had serious relationship problems used early intervention services to assist in resolving those problems (GPPS 2009; Table 3.13). There was less use of these services to support relationships by couples who had not faced serious problems (about 10%) (GPPS 2009; Table 3.12). Client satisfaction with early intervention services (funded as part of the federal Family Relationships Services Program) was high, with upwards of 88% of clients providing positive ratings for the "overall quality" of early intervention services. Favourable assessments for overall quality were made by 91% of Specialised Family Violence Service clients, 86% of Men and Family Relationships Services clients, 88% of counselling service clients and 95% of the Education and Skills Training service clients (Survey of FRSP Clients 2009; Table 3.28).

Overall, clients of post-separation services also provided favourable ratings. More than 70% of FRC and FDR clients said that the service treated everyone fairly (i.e., practitioners did not take sides) and more than half said that the services provided them with the help they needed (Survey of FRSP Clients 2009; Table 3.28). This rate can be considered to be quite high, given the strong emotions, high levels of conflict and lack of easy solutions that these matters often entail.

Family relationship service professionals generally rated their own capacity to assist clients as high (Online Survey of FRSP Staff 2009; Tables 3.21 & 3.22). They also spoke of considerable challenges associated with the complexity of many of the cases they are handling and of waiting times linked largely to resourcing and recruitment issues, especially in some of the FRCs.

Consistent with an important aim of the reforms, family relationship service professionals generally placed considerable emphasis on referrals to appropriate services. At the same time, ensuring that families are able to access the right services at the right time represents one important area where there is a need for ongoing improvement. Pathways through the system need to be more clearly defined and more widely understood. There is still evidence that some families with family violence and/or child abuse issues are on a roundabout between relationship services, lawyers, courts and state-based child protection and family violence systems. For example, compared with parents who did not report family violence, parents who reported family violence were much less likely to report that their parenting arrangements had been sorted out some 18 months after separation (LSSF W1 2008; Table 4.14) and were more likely to report using multiple services. While complex issues may take longer to resolve, resolutions that are delayed by unclear pathways or lack of adequate coordination between services, lawyers and courts have adverse implications for the wellbeing of children and other family members.

There is a need for more proactive engagement and coordination between family relationship service professionals and family lawyers and between family law system professionals and the courts. This need is especially important when dealing with complex cases.

Evaluation question 2: To what extent does FDR assist parents to manage disputes over parenting arrangements?

The use of FDR post-reform was broadly meeting the objectives of requiring parents to attempt to resolve their disputes with the help of non-court dispute resolution processes and services.

About two-fifths of parents who used FDR reached agreement and did not proceed to court (LSSF W1 2008; section 5.3.3). Almost a third did not reach agreement and did not have a certificate issued (under s60I(8) of the SPR Act 2006, family dispute resolution practitioners may issue these certificates to indicate that one or both parties has attempted to resolve a matter through FDR). However, most of these parents reported going on to sort things out mainly via discussions between themselves. About one-fifth were given certificates from a registered family dispute practitioner that permitted them to access the court system. Most of these parents mainly used courts and lawyers and approximately a year after separation most had neither resolved matters nor had decisions made.

Family Relationship Centres have also become a first point of contact for a significant number of parents whose capacity to mediate is severely compromised by fear and abuse, and there is evidence that FDR is occurring in some of these cases (Survey of FRSP Clients 2009; Tables 5.8 & 10.3), even though matters where there are concerns about family violence or child abuse are exceptions to the requirement to attend FDR (SPR Act 2006, s60I(9)). This may reflect an inadequate understanding of the exceptions to FDR by those making referrals. At the same time, the complexities of this process need to be acknowledged. There are decisions that need to be made on a case-by-case basis, including decisions about who is best placed to make a judgment concerning whether there are grounds for an exception and the extent to which professionals should respect the wishes of those who qualify as an "exception" but nonetheless opt for FDR.

Clearer inter-professional communication (between FDR professionals, lawyers and courts) will not provide prescriptive answers to such questions but would assist in developing strategies to ensure that there is a more effective process of sifting out matters that should proceed as quickly as possible into the court system. Progress on this front, however, also requires earlier access to courts and greater confidence on the part of lawyers and service professionals that clients will not get "lost in the family law system".

Evaluation question 3: How are parents exercising parental responsibility, including complying with obligations of financial support?

In lay terms, parental responsibility has a number of dimensions, including care time, decision-making about issues affecting the child, and financial support for the child. Shared decision-making is most likely to occur where there is shared care time.

Shared decision-making was much less common among parents who reported a history of family violence or had ongoing safety concerns for their children (LSSF W1 2008; section 8.1.3). Nonetheless, the exercise of shared decision-making was reported by a substantial proportion of parents with a history of violence. For example, shared decision-making about the child's education was reported by 25% of fathers and 15% of mothers who said that their child's other parent had hurt them physically and whose child was in a care arrangement involving most or all nights with the mother. Where a history of physical hurt was reported and the child was in a shared care arrangement, 54% of fathers and 42% of mothers reported shared decision-making over education.

In contrast to the systematic variation in decision-making practices reported by parents with different care-time arrangements, legal orders concerning parental responsibility demonstrated a strong trend, pre-dating the reforms, for decision-making power to be allocated to both parents. Prior to the reforms, court orders provided for shared parental responsibility in 76% of cases, compared with 87% after the reforms (QSCF 2009; Table 8.2). Generally, fathers' compliance with their child support liability did not vary according to care-time arrangements. The only exception is that fathers who never saw their child were less likely to comply with their child support obligations. (LSSF W1 2008; Figures 8.17 & 8.18). Father payers with equal care time and those who never saw their child were more inclined to believe that child support payments were unfair, compared to father payers with other care-time arrangements (LSSF W1 2008; Figure 8.23). Child support compliance among fathers and mothers was higher where there was shared decision-making compared to where one parent had all of the decision-making responsibilities (LSSF W1 2008; Figure 8.19).

Evaluation question 4: What arrangements are being made for children in separated families to spend time with each parent? Is there any evidence of change in this regard?

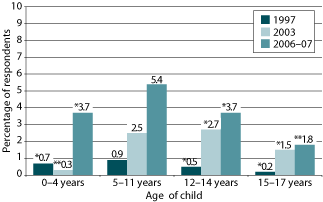

Although only a minority of children were in shared care-time arrangements, the proportion of children with these arrangements has increased; a trend that appears to pre-date the reforms. In the LSSF W1 2008, 16% of focus children were in shared care arrangements (applying a definition based on a 35-65% night split between parents). A near equal time split (48-52% of nights) applied to 7% of children, with another 8% spending more time with their mother than their father and 1% spending more time with their father than their mother (LSSF W1 2008; section 6.5.1) Incremental increases in shared care are part of a longer term trend in Australia and internationally. Australian Bureau of Statistics data show increases in shared care arrangements across age groups between 1997 and 2006-07 (Figure 1 below). Shared care for children in the 5-11 year age group rose from 1% in 1997 to 5% in 2006-07. Increases were less marked for children in other age groups, although estimates for these age groups should be used with caution due to small sample sizes. In relation to 12-14 year olds, for example, less than 1% of children were in shared care arrangements in 1997, compared with 3.7% in 2006-07.

Figure 1: Proportion of children in different age groups who experienced equal care-time arrangements, by age of child, 1997, 2003 and 2006-07

Notes: Omitted from analysis are data for children who lived with grandparents or guardians and for those whose overnights stays were not stated. * These estimates had a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution. ** These estimates have a relative standard error greater than 50% and are considered to be too unreliable for general use.

Source: ABS FCS 1997 and 2003, ABS FCTS 2006-07

Judicially determined orders for shared care time increased post-reform, as did shared care time in cases where parents reached agreement by consent. Data from the QSCF 2009 show that orders for shared care in matters decided by judges (again applying a definition based on a 35-65% night split) rose from 2% prior to the reforms to 13% after the reforms (Table 6.8). A less significant increase was evident among cases in which the parties reached agreement, with a pre-reform proportion of 10% compared with 15% post reform (Table 6.9).

The majority of parents with shared care-time arrangements thought that the parenting arrangements were working well both for parents and the child (LSSF W1 2008; Figure 7.21). While, on average, parents with shared care time had better quality inter-parental relationships, violence and dysfunctional behaviours were present for some. For example, 16% of mothers and 10% of fathers with shared care (more nights with mother) reported relationships with "lots of conflict", and 8.4% of mothers and 3.5% of fathers with such arrangements reported relationships that were fearful (LSSF W1 2008; Figures 7.27 & 7.28).

Generally, shared care time did not appear to have a negative impact on the wellbeing of children. Irrespective of care-time arrangements, mothers and fathers who expressed safety concerns described their child's wellbeing less favourably than those who did not hold such concerns (LSSF W1 2008; section 11.3.2). However, the reports of mothers suggest that the negative impact of safety concerns on children's wellbeing is exacerbated where they experience shared care-time arrangements (LSSF W1 2008; Figure 11.11 & 11.12).

Evaluation question 5: What arrangements are being made for children in separated families to spend time with grandparents? Is there any evidence of change in this regard?

Just more than half of the parents who separated after the 2006 changes to the family law system felt that time with grandparents had been taken into account when developing parenting arrangements, and just over half the grandparents confirmed this view. Parents who separated prior to the 2006 changes to the family law system were less likely to recall having taken into account grandparents when developing parenting arrangements (LSSF W1 2008; LBS 2009; Figure 12.12).

Nevertheless, the reports of both parents and grandparents suggest that relationships between children and their paternal grandparents often become more distant when the child lives mostly with the mother (reflecting the most common care-time arrangement) (GPPS 2006; GPPS 2009; Figures 12.7 & 12.8). The parents in most families in the studies would have separated before the reforms were introduced. The level of impact of the reforms on the evolution of grandparent-grandchild relationships is an important area for future research.

There appeared to be a growing awareness among both family relationship service staff and family lawyers of the potential value and importance to children of taking into account grandparents when developing parenting arrangements. While grandparents were seen, in most cases, to have the potential to contribute much to the wellbeing of children, there was also an appreciation by family relationship service professionals of the complexity of many extended family situations (Qualitative Study of FRSP Staff 2008-09; section 12.7.2). This was associated with recognition that, in some cases, too great a focus on grandparents when developing parenting arrangements might be counter-productive.

The overall picture, however, is of grandparents being very important in the lives of many children and their families, with some evidence that the legislation has contributed to reinforcing this message. Clearly, grandparents can also be an important resource when families are struggling during separation and at other times. But as complexities increase, dispute resolution and decision-making in cases involving grandparents are likely to prove to be more difficult and time-consuming.

Evaluation question 6: To what extent are issues relating to family violence and child abuse taken into account in making arrangements regarding parenting responsibility and care time?4

For a substantial proportion of separated parents, issues relating to violence, safety concerns, mental health, and alcohol and drug misuse are relevant. The evaluation provides evidence that the family law system has some way to go in being able to respond effectively to these issues. However, there is also evidence of the 2006 changes having improved the way in which the system is identifying families where there are concerns about family violence and child abuse. In particular, systematic attempts to screen such families in the family relationship service sector and in some parts of the legal sector appear to have improved identification of such issues.

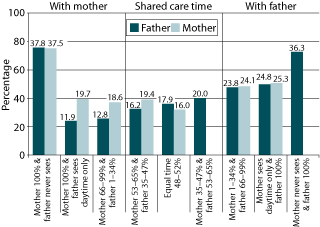

Families where violence had occurred, however, were no less likely to have shared care-time arrangements than those where violence had not occurred (LSSF W1 2008; Figures 7.29 & 7.30). Similarly, families where safety concerns were reported were no less likely to have shared care-time arrangements than families without safety concerns (16-20% of families with shared care time had safety concerns). Safety concerns were also evident in similar proportions of families with arrangements involving children spending most nights with the mothers and having daytime-only contact with the father (LSSF W1 2008; Figure 7.31 [see Figure 2 below]). The pathways to these arrangements included decisions made without the use of services and decisions made with the assistance of family relationship services, lawyers and courts (Kaspiew et al., 2009, pp. 232-233).

Figure 2: Safety concerns associated with ongoing contact, by care-time arrangements, fathers and mothers, 2008

Source: LSSF W1 2008

Mothers and fathers who reported safety concerns tended to provide less favourable evaluations of their child's wellbeing compared to other parents (LSSF W1 2008; section 11.3.2). This was apparent for parents with all care-time arrangements, including the most common arrangement. where the child lives mainly with mother. But the poorer reported outcomes for children whose mothers expressed safety concerns were considerably more marked for those children who were in shared care-time arrangements.

There is also evidence that encouraging the use of non-legal solutions, and particularly the expectation that most parents will attempt FDR, has meant that FDR is occurring in some cases where there are very significant concerns about violence and safety (Survey of FRSP Clients 2009; Table 10.3).

Significant concerns were expressed by substantial minorities of lawyers and family relationship service professionals who expressed the view that the system had scope for improvement in achieving an effective response to family violence and child abuse (FLS 2008; Online Survey of FRSP Staff 2009; e.g., Figure 10.3). Some problems referred to were evident before the reforms, such as difficulties arising from a lack of understanding among professionals, including lawyers and decision-makers, about family violence and the way in which it affects children and parents (FLS 2008; QSLSP 2008; section 10.4.1). While the legislation (SPR Act) sought to place more emphasis on the importance of identifying concerns about family violence and child abuse (e.g., s60B(1)(b); 60CC(2)(b)), other aspects of the legislation were seen to contribute to a reticence among some lawyers and their clients about raising such concerns; for example, s117AB, which obligates courts to make a costs order against a party found to have "knowingly made a false allegation or statement" in proceedings, and s60CC(3)(c), which requires courts to consider the extent to which a parent has facilitated the other parent's relationship with the child.

The link between safety concerns and poorer child wellbeing outcomes, especially where there was a shared care-time arrangement, underlines the need to make changes to practice models in the family relationship services and legal sectors. In particular, these sectors need to have a more explicit focus on effectively identifying families where concerns about child or parental safety need to inform decisions about care-time arrangements.

These findings point to a need for professionals across the system to have greater levels of access to finely tuned assessment and screening mechanisms applied by highly trained and experienced professionals. Protocols for working constructively and effectively with state-based systems and services (such as child protection systems) also need further work. Clearly, however, the progress that continues to be made on improved screening practices will go only part of the way towards assisting victims of violence and abuse.

Evaluation question 7: To what extent are children's needs and interests being taken into account when parenting arrangements are being made?

This question is central to the objectives of the reforms and therefore a number of the evaluation questions are relevant to assessing the extent to which children's needs and interests are being taken into account. Particularly relevant is the question of the extent to which issues relating to family violence and child abuse are taken into account when making arrangements regarding parenting responsibility and care time.

This is an area where the evaluation evidence points to some encouraging developments, but also highlights some difficulties. Many parents are using the relationship services available and there is evidence from clients and service professionals that this is resulting in arrangements that are more focused on the needs of children than in the past. Nonetheless, in a proportion of cases this is not occurring as well as it could.

There is evidence that many parents misconstrue equal shared parental responsibility as allowing for "equal" shared care time (FLS 2008; QSLSP 2008; Qualitative Study of FRSP Staff 2008-09; section 9.3). In cases in which equal or shared care time would be inappropriate, this can make it more difficult for relationship service professionals, lawyers and courts to encourage parents to focus on the best interests of the child (discussed further below).

The SPR Act 2006 introduced Division 12A of Part VII - Principles for conducting child related proceedings - which was supported by new case management practices in the Family Court of Western Australia (FCoWA) and the Family Court of Australia (FCoA). The court that handles most children's matters, the Federal Magistrates' Court (FMC) had largely retained it own case management regime based on the "docket" system.

Evaluation question 8: How are the reforms introduced by the SPR Act 2006 working in practice?

The philosophy of shared parental responsibility is overwhelmingly supported by parents, legal system professionals and service professionals (LSSF W1 2008; FLS 2008; Figures 6.1, 6.2 & 9.1). However, many parents and some professionals do not understand the distinction between shared parental responsibility and shared care time, or the rebuttable (or non-applicable) presumption of shared parental responsibility (FLS 2006; QSLSP 2008; section 9.2). A common misunderstanding is that shared parental responsibility allows for "equal" shared care time, and that if there is shared parental responsibility, then a court will order shared care time. This misunderstanding is due, at least in part, to the way in which the link between equal shared parental responsibility and care time is expressed in the legislation. This confusion has resulted in disillusionment among some fathers, who find that the law does not provide for 50-50 "custody". This in turn can make it challenging to achieve child-focused arrangements in cases in which an equal or shared care-time arrangement is not practical or not appropriate. Legal sector professionals in particular indicated that in their view the legislative changes had promoted a focus on parents' rights rather than children's needs, obscuring to some extent the primacy of the "best interests" principle (s60CA). Further, they indicated that, in their view, the legislative framework did not adequately facilitate making arrangements that were developmentally appropriate for children.

However, the changes have also encouraged more creativity in making arrangements, either by negotiation or litigation, that involve fathers in children's everyday routines, as well as special activities. Advice-giving practices consistent with the informal "80-20" rule (i.e., what was seen as the typical arrangement where the child spends 80% of the time with the mother and 20% of the time with the father post-separation) have declined markedly since the reforms (FLS 2006 & 2009; section 9.4.2). For example, lawyers indicated that advice that "mothers who have had major child care responsibilities would normally obtain residence of their children" was given much less frequently in 2008 than in 2006: pre-reform, 82% of participants in the FLS 2006 said they gave this advice almost always or often, compared with 44% in 2006. Similarly, advice indicating that a normal contact pattern was "alternate weekends and half school holidays" was given much less frequently after the reforms: pre-reform, 26% of the FLS 2006 sample said they "rarely or never" gave such advice, compared with 64% in 2008.

In an indication of the impact of the measures designed to reduce reliance on legal mechanisms to resolve disputes, total court filings in children's matters have declined by 22%; and a pre-reform trend for filings to increase in the FMC, with a corresponding decrease in the FCoA, has gathered pace (QSCF 2009; section 13.2).

Legal sector professionals had concerns arising from the parallel operation of the FMC and FCoA, including the application of inconsistent legal and procedural approaches and concerns about whether the right cases are being heard in the most appropriate forum (FLS 2006; QSLSP 2008; section 14.1). The FCoA, the FMC and the FCoWA have each adopted a different approach to the implementation of Division 12A of Part VII (FLS 2006; QSLSP 2008; section 13.1). FMC processes have changed little (although this court is perceived to have an active case management approach pre-dating the reforms) and the FCoA and FCoWA have implemented models with some similarities, including limits on the filing of affidavits and roles for family consultants that are based on pre-trial family assessments and involvement throughout the proceedings where necessary. Excluding WA, the more child-focused process available in the FCoA is only applied to a small proportion of children's matters, with the majority of such cases being dealt with under the FMC's more traditional adversarial procedures.

While family consultants and most judges believed the FCoA's model is an improvement, particularly in the area of child focus, lawyers' views were divided, with many expressing hesitancy in endorsing the changes (QSLSP 2008; FLS 2006; FLS 2008; section 14.3). Concerns include a lack of resources in the FCoA leading to delays, more protracted and drawn-out processes, and inconsistencies in judicial approaches to case management. Similar concerns were evident to a lesser extent about the WA model. It appears that while these models have significant advantages, some fine-tuning is required. This is an area where the Evaluation provided only a partial picture, as these issues were considered as part of a much larger set of evaluation questions.

The new substantive parenting provisions introduced into Part VII of the FLA by the SPR Act 2006 tended to be seen by lawyers and judicial officers to be complex and cumbersome to apply in advice-giving and decision-making practice (QSLSP 2008; FLS 2006; section 15.1). Because of the complexity of key provisions, and the number of provisions that have to be considered or explained, judgment-writing and advice-giving have become more difficult and protracted. There is concern that legislation that should be comprehensible to its users - parents - has become more difficult to understand, even for some professionals.

Evaluation question 9: Have the reforms had any unintended consequences - positive or negative?

The majority of parents in shared care-time arrangements reported that the reforms worked well for them and for their children. But up to one-fifth of separating parents had safety concerns that were linked to parenting arrangements; and the data on child wellbeing from the LSSF W1 2008 show that shared care time in cases where there are safety concerns expressed by mothers correlates with poorer outcomes for children (Figures 11.11 & 11.12).

Similarly, the majority of parents who attempted FDR reported that it worked well. Most had sorted out their arrangements and most had not seen lawyers or used the court as their primary dispute resolution pathway. But many FDR clients had concerns about violence, abuse, safety, mental health or substance misuse. Some of these parents appeared to attempt FDR where the level of their concerns was such that they were unlikely to be able to represent their own needs or their children's needs adequately. It is also important to recognise that FDR can be appropriate in some circumstances in which violence has occurred (section 5.3.2).

Further unintended consequences are also evident. A majority of lawyers perceived that the reforms have favoured fathers over mothers (FLS 2006; FLS 2008; Figure 9.8) and parents over children (FLS 2006; FLS 2008; Figure 9.9). There was concern among a range of family law system professionals that mothers have been disadvantaged in a number ways, including in relation to negotiations over property settlements (FLS 2008; QSLSP 2008; section 9.6.2). There was an indication from lawyers that there may have been a reduction in the average property settlements allocated to mothers. Financial concerns, including child support liability and property settlement entitlements, were perceived by many lawyers and some family relationship professionals to have influenced the care-time arrangements some parents sought to negotiate (FLS 2006; QSLSP 2008; Qualitative Study of FRSP Staff 2008-09; section 9.6). The extent to which these concerns are generally pertinent to separated parents is uncertain. The evaluation indicates that a majority of parents are able to sort out their post-separation parenting arrangements quickly and expeditiously; however, there is also a proportion whose post-separation arrangements appear to have been informed by a "bargaining" rather than "agreeing" dynamic. For these parents, it appears the reforms have contributed to a shift in the bargaining dynamics. This is an area where further research is required.

Conclusion

The evaluation evidence indicates that the 2006 reforms to the family law system have had a positive impact in some areas and have had a less positive impact in others. Overall, there has been more use of relationship services, a decline in filings in the courts in children's cases, and some evidence of a shift away from an automatic recourse to legal solutions in response to post-separation relationship difficulties.

A significant proportion of separated parents are able to sort out their post-separation arrangements with minimal engagement with the formal system. There is also evidence that FDR is assisting parents to work out their parenting arrangements.

A central point, however, is that many separated families are affected by issues such as family violence, safety concerns, mental health problems and substance misuse issues, and these families are the predominant users of the service and legal sectors. In relation to these families, resolution of post-separation disputes presents some complex issues for the family law system as whole, and the evaluation has identified ongoing challenges in this area. In particular, professional practices and understandings in relation to identifying matters where FDR should not be attempted require continuing development. This is an area where collaboration between relationship service professionals, family law system professionals and courts needs to be facilitated so that shared understandings about the types of matters that are not suitable for FDR can be developed and so that other options can be better facilitated.

Beyond effective screening, possible ways forward include:

- continued development of protocols for the sharing of information within the family relationship service sector and between the sector and other critical areas, such as child protection;

- development of protocols for cooperation between family relationship service professionals and independent children's lawyers;

- development of protocols for cooperation between family relationship service professionals and lawyers acting as advocates for individual parents;

- a considerably improved capacity in courts to solicit or provide high-quality assessments that will assist them to make safe, timely and child-focused decisions, especially at the interim stage; and

- consideration of whether (and, if so, how) information already gained via sometimes extensive screening procedures within the family relationship service sector can be used by judicial officers or by those providing court assessments to assist in the process of judicial determination.

While communication in relation to privileged and confidential disclosures made during assessment and FDR processes raises some complex questions, investigation of how such communication could potentially occur may be an avenue for achieving greater coordination and ensuring expeditious handling of these matters. Currently, much relevant information may be collected by family relationship service professionals in screening and assessment processes, but this information is not transmissible between professionals in this sector and professionals in the legal sector, or between other agencies and services responsible for providing assistance. Effectively, families who move from one part of the system to the other often have to start all over again. For families already under stress as a result of family violence, safety concerns and other complex issues, this may delay resolution and compound disadvantages.

Effective responses to families where complex issues exist mean ensuring such families have access to appropriate services to not only resolve their parenting issues but also deal with the wider issues affecting the family. Such responses involve identifying concerns and assisting parents to use the dispute resolution mechanism that is most appropriate for their circumstances.

Effective responses should ensure that the parenting arrangements put in place for children in families with complex issues are appropriate to the children's needs and do not put their short- or long-term wellbeing at risk. Further examination of the needs and trajectories of families who are unsuitable for FDR would assist in identifying the measures required to assist these families (to some extent, LSSF W2 2009 [forthcoming] may assist with this). A key question is the extent to which such families then access the legal/court system and whether there are barriers or impediments (e.g., financial or personal) to them doing so.

The evidence of poorer wellbeing for children where there are safety concerns - across the range of parenting arrangements, but particularly acutely in shared care-time arrangements - highlights the importance of identifying families where safety concerns are pertinent and assisting them in making arrangements that promote the wellbeing of their children.

This evaluation has highlighted the complex and varied issues faced by separating parents and their children and the diverse range of services required in order to ensure the best possible outcomes for children. Ultimately, while there are many perspectives within the family law system, and many conflicting needs, it is important to maintain the primacy of focusing on the best interests of children and protecting all family members from harm.

Endnotes

1 The Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth) (SPR Act 2006) amended the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (FLA 1975). As this report is oriented toward a broad audience rather than a specifically legal one, references to provisions introduced by the SPR Act will be preceded by "SPR Act", for the sake of simplicity and clarity. Technically, of course, such provisions are FLA provisions.

2 Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Bill 2005, Explanatory Memorandum, p. 1.

3 For further details, see the 2007 Evaluation Framework, reproduced in the full evaluation report (Kaspiew et al., 2009).

4 A detailed summary of the AIFS Evaluation findings on family violence and child abuse appeared in Kaspiew R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., and Qu L. (2010). Family violence: Key findings from the AIFS Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms. Family Matters, 85, 38.

References

- Family Law Act 1975 (Cth)

- Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 (Cth)

- Explanatory Memorandum to the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Bill 2005 (Cth)

- Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., Qu, L., & the Family Law Evaluation Team. (2009). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Appendix

The Legislation and Courts Project

The LCP was designed to gather data on the impact that the legislative changes have had on: (a) advice-giving practices; (b) negotiation and bargaining among those who sought the advice and assistance of lawyers; (c) how the main new legislative provisions were applied in court decisions; and (d) how court filings were affected by the reforms. A further priority was to examine what, if any, unintended consequences may have arisen as a result of the changes.

The LCP encompassed five components:

- the Qualitative Study of Legal System Professionals (QSLSP) 2008;

- the Family Lawyers Surveys (FLS) 2006 and 2008;

- analysis of FCoA, FMC and FCoWA judgments, 2006-09;

- analysis of FCoA, FMC and FCoWA court files, pre- and post-1 July 2006; and

- analysis of FCoA, FMC and FCoWA administrative data, 2004-05 to 2007-08.

Qualitative Study of Legal System Professionals 2008

The QSLSP 2008 involved interviews and focus groups with family law system professionals in order to gather data on professionals' experiences of the reforms. A total of 184 professionals participated in interviews and/or focus groups between April and October 2008. In order to gain insights from as many angles on the legal system and court process as possible, participants were drawn from the following professional groupings: FCoA judges; federal magistrates; FCoWA judges and magistrates; FCoA registrars; family consultants operating in the FMC, FCoA and FCoWA; barristers; and solicitors from private practice, legal aid and community legal centres.

The Family Lawyers Surveys

The purpose of the FLS 2006 was to provide baseline (pre-reform data) about lawyer practices and attitudes at the time of the implementation of the reforms. The FLS 2008 substantially repeated and extended the FLS 2006, thereby allowing pre- and post-reform shifts to be gauged. The FLS 2008 allowed important insights from the QSLSP 2008 to be tested in a quantitative format.

The two surveys were conducted online, with the first taking place in mid-2006 and the second from mid-November 2008 to early February 2009. Both samples were recruited with the assistance of the Family Law Section of the Law Council of Australia. The first comprised 367 participants. The second comprised 319 participants.

FCoA, FMC and FCoWA court files

The aim of this component was to gather systematic quantitative data from court files (FCoA, FMC and FCoWA). Part 1 involved the collection of data from matters initiated and finalised after the reforms (total of 985 files), including matters finalised by consent (752 files) and judicial determination (233 files) in the FCoWA and the Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane registries of the FMC and the FCoA. Part 2 involved the collection of data from matters initiated and finalised prior to the reforms (739 files: 188 judicial determination files and 551 consent files) in the FCoWA and the Melbourne Registry of the FCoA and the FMC.

The Service Provision Project

This part of the evaluation provided information on the operation and effectiveness of the delivery of family relationship services, including the Family Relationships Advice Line (FRAL), FRCs, and early intervention and post-separation services that were funded as part of the reform package. Information on services was obtained from service providers and clients.

The services included in the evaluation can be categorised as early intervention services (EIS) or post-separation services (PSS). The early intervention services are: Specialised Family Violence Services, Men and Family Relationships Services, family relationship counselling, Mensline, and Family Relationship Education and Skills Training. The post-separation services are: FRCs, FDR, Children's Contact Services, the Parenting Orders Program, FRAL, and the Telephone Dispute Resolution Service (TDRS; a component of FRAL).

The components of the Service Provision Project were: the Qualitative Study of FRSP Staff; the Online Survey of FRSP Staff; the Survey of FRSP Clients; and analyses of administrative program data (FRSP Online, FRAL, TDRS and Mensline).

Qualitative Study of FRSP Staff

This component of the SPP collected information via in-depth interviews with managers and staff of family relationship services funded under the new and expanded service delivery system. The purpose of this aspect of the evaluation was to evaluate the roll-out of the new and expanded services. It also helped to identify any other issues that needed to be explored by other components of the evaluation.

Two data collections were undertaken. The first was undertaken between August 2007 and April 2008 and the second took place from February to November 2009. These studies provide information about the extent to which changes have occurred in the operation and performance of the service sector during the roll-out period.

The Qualitative Study of FRSP Staff 2007-08 involved interviews with organisational Chief Executive Officers, managers and staff (137 participants in 57 interviews) from the first 15 FRCs, 8 early intervention services, 8 post-separation services, Mensline and FRAL. The Qualitative Study of FRSP Staff 2008-09 involved interviews with managers and staff from all of these services, with the addition of staff from a further 10 FRCs, a further 10 post-separation services and the TDRS.

The Families Project

The Families Project comprised a number of studies of families (both cross-sectional and longitudinal):

- the General Population of Parents Survey 2006 and 2009;

- Family Pathways: The Longitudinal Study of Separated Families Wave 1 2008 and Wave 2 2009;

- Family Pathways: Looking Back Survey 2009; and

- Family Pathways: The Grandparents in Separated Families Study 2009.

This series of individual studies included surveys of parents in general and of parents who had experienced separation. Other components focused on grandparents with a grandchild living in a separated family. Together, this suite of studies sought to understand how changes to the family law system and changes to the Child Support Scheme affected the lives of families, particularly separated parents and their children.

Family Pathways: The Longitudinal Study of Separated Families

The LSSF is a national study of 10,000 parents (with at least one child less than 18 years old) who separated after the introduction of the reforms in July 2006. The study involves the collection of data from the same group of parents over time. These parents had: (a) separated from the child's other parent between July 2006 and September 2008; (b) registered with the Child Support Agency (CSA) in 2007; and (c) were still separated from the other parent at the time of the first survey. Where the separated couple had more than one child together who was less than 18 years old at the time of the survey, most of the child-related questions that were asked focused on only one of these children (here called the "focus child").

The LSSF W1 2008 took place between August and October 2008, up to 26 months after the time of parental separation. The final overall response rate for LSSF W1 2008 was 60.2%. An equal gender split was achieved. The majority of participants were aged between 25 and 44 years (74%) and were born in Australia (83%).

Family Pathways: Looking Back Survey

The LBS 2009 is a national study of 2,000 parents with at least one child under 18 years old, who separated from their partner between January 2004 and June 2005, prior to the introduction of the reforms. The study involved a one-off interview with parents who were registered with the CSA in 2007.

Parents were interviewed for this study between March and May 2009; 3.7 to 5.2 years after separation. The final overall response rate was 69% and an almost equal gender split was achieved. The majority of participants were aged between 25 and 44 years (72%) and were born in Australia (83%).

The cross-sectional study design provided a snapshot of the reflections of separated parents about what life was like for them during and after separating in the pre-reform period and about the pathways they followed.

Rae Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., Qu, L., & the Family Law Evaluation Team. (2011). The AIFS evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms: A summary. Family Matters, 86, 8-18.