Conference Keynote. Two-generation programs:

Can 1 + 1 be more than 2?

April 2017

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Two-generation programs provide coordinated services to both parents and children - for example, early childhood education complemented with a parenting skills program. In this article, based on his keynote address given at the 16th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference, Distinguished Professor Greg Duncan looks at the potential of two-generation programs to benefit families - such as by closing the school achievement gap between children of high and low socio-economic status or reducing 'toxic stress' in the home. In particular, he discusses evidence from overseas on whether two-generation programs, run synergistically, have more impact on parents' and children's outcomes than two separate programs.

Two-generation programs provide services to both parents and children. Their goal is to help disadvantaged families by coordinating services offered to parents and children in synergistic combinations.

In this talk, I will focus on the potential of two-generation programs to close the school achievement gap between children of high and low socio-economic status (SES). The gap, as we shall see, is already present at kindergarten. So, one possible aim of two-generation programs is to deploy a variety of child- and parent-based services and programs to help close the gap before the child enters school.

My main interest is in whether a combination of these child- and parent-based programs will be more effective than either one alone.

Looking at the gap

We all know that children growing up in low-SES families tend to do worse in terms of achievement than children growing up in higher-SES families. This is borne out by comparative data based on research by Bruce Bradbury and colleagues (2015) and published in a book called Too Many Children Left Behind. It is a comparative study of the relative wellbeing of children and families in Australia, the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. For the purpose of this discussion, I will highlight the US and Australian data.

The book compares children whose mothers are college graduates - which indicates high SES - and children whose mothers did not attend college at all. The Australian data were drawn mainly from the Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (LSAC), conducted in partnership between the Australian Institute of Family Studies, Department of Social Services, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

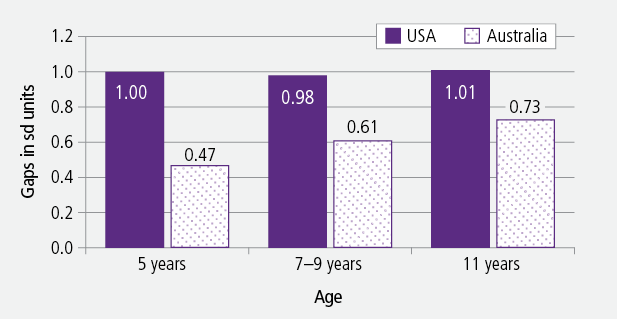

In the United States, Bradbury and colleagues (2015) found gaps of 1.00 standard deviation between children in high- and low-SES families in their kindergarten-entry achievement test scores.

One standard deviation is huge. It corresponds to what children typically learn over the course of kindergarten, in an entire year. A 1.00 standard deviation tells us that when school starts, children growing up in low-SES families are already a year behind high-SES children. The gap in Australia is smaller: about half a standard deviation. In other words, low-SES children in Australia are about half a year behind their high-SES counterparts when they enter school.

It's interesting to see how these gaps change as children progress through the education system (see Figure 1). One might hope that schools would serve as equalising agents and reduce the school-entry gaps. In the United States, unfortunately, this does not appear to be the case. Indeed, several years later, when children are 7 and 9 years old, the gaps are just as large. In Australia, the gaps begin much smaller than in the United States but grow by 50% over the first six years of school.

So while the school years clearly matter, these data from the United States show the importance of trying to get things right in the first few years.

Source: Adapted from Bradbury et al., 2015

Figure 1: Achievement gaps in the first six years of school for children born to mothers who are college graduates relative to children whose mothers did not attend college, by child's age and standard deviation units

In our book Whither Opportunity (Duncan & Murnane, 2011), Richard Murnane and I looked at the US data on child "enrichment" expenditures over the past 40 years. (There are comparable data on this in Australia, but no-one appears to have done the analysis.) Enrichment spending includes lessons, private schools, summer camps, computers and the like. In the United States today, private enrichment expenditures by high-SES families (the top 20% of families ranked by income) average almost $10,000 per child, per year. This also happens to be about what schools spend on each child. Four decades ago, enrichment expenditures by high-SES families averaged only about $3,300 per child; now they are three times that amount. So schools are fighting a huge headwind when they try to reduce these achievement gaps. (It would be interesting to know whether a similar situation exists in Australia.)

The data in Figure 1 motivate the work we will turn to now: exploring the potential for two-generation programs to close some of the gaps.

The potential of two-generation programs

When it comes to two-generation programs for younger children, child-based programs typically focus on early care and early education. Both the United States and Australia have systems and subsidies for these kinds of child-based programs. Parent-based programs include parenting-skills programs, delivered via home visitation and via the classroom. There are also parent-based programs that focus on the parents' job or language skills.

Two-generation programs combine a child-based program - early childhood education, for example - with one of these kinds of parenting-skills programs. The question for policy-makers is whether you get more bang for your buck by combining the two. In other words, does one plus one equal more than two? The answer is yes if the programs complement one another - if they're synergistic. But they're not going to add up even to two if they substitute for one another - if they're redundant to some extent in the kind of programming that they offer.

It turns out to be very difficult to point to instances where one plus one is greater than two; this is a very high standard to meet. You can have an effective child program and an effective parenting program that both pass the cost-benefit test, so that both are sensible policies, but they still might not be synergistic.

Assessing outcomes of two-generation programs

What sort of evidence is there for one plus one being greater than two? A project (Grindal et al., 2016) of which I'm part is conducting a meta-analysis that is trying to synthesise research published between 1960 and 2007 on intervention programs directed towards young children and their families. For this particular analysis, we took the subset of evaluations that compared programs that included both early education programming and some sort of parenting program with programs that offered only the education programming. We then looked to see whether adding a parenting component improved children's achievement-related outcomes.

All told, Grindal el al. (2016) examined 321 cognitive and achievement impacts from 46 studies and found that, for the most part, one plus one equals … one. In other words, there were no significant differences in the achievement outcomes of programs with and without the parenting component - a very disappointing result. There was some indication that programs that combine early education with home visitation had somewhat more positive outcomes than those that included only the early education component, but the difference wasn't even close to being statistically significant. And the same result held when we compared classroom parenting-programs with parent-modelling programs. In this case, there was some slight indication that the parent-modelling programs may have performed better, but the bottom line from the literature is that these parenting components, at least as they have been assessed in existing evaluation studies, haven't added significantly to what the early education programs can do. In this case, one plus one equals one.

Or does it? A remarkable Danish study (Rossin-Slater & Wüst, 2016) was too recent to make it into the Grindal et al. (2016) research. It took advantage of the fact that over the 27-year period, beginning in 1933, Denmark rolled out fairly high quality home-visitation and early-education programs across its municipalities in a rather haphazard kind of way. An assessment of the impacts of these programs was made possible by wonderfully complete Danish administrative data.

This leads me to my first aside, on the importance of administrative data. Denmark and other Scandinavian countries have administrative registers that follow children growing up in different municipalities. Rossin-Slater and Wüst used these data to examine, years later, how much schooling these children had completed and how much they earned when they entered the labour market. The data also cover mortality and health, and can even link these children to the children that they eventually bear. So you can answer the question, "Does growing up in a municipality that had one or both of these programs boost these outcomes - education, wages and health - in the first generation (for the children who actually may have taken up the programs) and for these children's children?" I know that there are efforts in Australia - there certainly are in the United States - to put together administrative data from various sources, with due regard for privacy issues. This study gives you an idea of the power of linked administrative data to understand program impacts for programs that may have been operating decades ago.

Rossin-Slater and Wüst compared children who were old enough (and lucky enough) to live in a municipality with an early education program with slightly older children who just missed the opportunity to be in that municipality's early-care or home visitation program. These comparisons are between very similar children who are only a couple of years apart, but it just happened that some of them were able to participate in the program and some were born a little bit too early and missed it.

They found that the children in the municipalities with early education programs completed more schooling, earned higher wages, enjoyed better health and had children who completed more schooling than children who missed that opportunity. The impacts were about a tenth of a year of schooling, but only 10% of the children in a municipality, on average, participated in the program. So if you ask, "What's the likely effect of this program on the children who were actually in the program?" you'd scale it up by a factor of 10, and then you're getting more than an extra year of completed schooling for participating in the early education program - a quite respectable effect size.

In the case of the Danish home visitation program, they found very similar kinds of benefits. The children whose parents were in home visitation programs but who were not living in a municipality with early education also ended up with more schooling, higher earnings and better health. In the case of these home visitation programs, there was no detectable second-generation impact (that is, there was no impact on the children's children). But in terms of impacts on the children themselves, their long-run prospects were improved by both of these programs.

Taken in isolation, each program appears to have provided long-term benefits for the children who participated in them. And while it might be hoped that the combination would produce even better results, the bottom line is that when the two programs were combined, the benefits were less than the sum of the parts: The combination added only about 20% to the benefits of having one or the other. So, in this case, the apparent redundancy meant that 1 + 1 only equalled 1.2.

A substantial random assignment evaluation literature in the United States has arisen around a number of teen parent interventions with two-generation programming. New Chance and the Teen Parent Demonstration are two of the most prominent examples. These well-intentioned efforts provided job skills and life-skills training to the parents, coupled with child care and early education opportunities for the children. But these studies produced uniformly disappointing results. Very few significant differences emerged for the mothers and children who were in these programs relative to the mothers and children who weren't. So, in this literature, you again see little synergy between efforts to address the needs of both generations.

A huge problem that many of these programs encounter is in getting parents to show up for them. Parents lead complicated lives, especially now that there is a big push for them to be working full-time. So if you couple a parent program and a child program - if you force the two to be offered simultaneously - you might build in a kind of inflexibility that could lead the combination to be worse than offering the two separately.

After reviewing past programs, Chase-Lansdale and Brooks-Gunn (2014) highlight, at least for the United States, some new ideas for two-generation programs. With regard to parent skills, the newer programs are very much focused on employment skills, with the idea that if you can boost those skills and combine those efforts with a very high quality early-education program system, you might achieve synergistic effects. The jury is still out - but that's the direction that's being taken in the United States.

In sum, I can't find any solid evaluation evidence that one plus one is greater than two, or even that one plus one equals two. So I don't think, based on the evidence, that we can be confident that the combination of these programs will always, or even ever, be synergistic. By all means, we should keep trying, and we should keep evaluating what we are trying. Parents and children certainly have unmet needs. We have effective programs for addressing some of these needs, but coupling them together may just be too rigid and complicated. In short, the news is not as good as it might be, but it should inspire us to try to learn from the past and develop program models that do work.

Parent-based programs and toxic stress

Now I want to turn to two-generation programs of a different kind: parent-based programs, which, without providing separate programming for children, improve parents' lives sufficiently to generate benefits for their children. Low-hanging fruit in this context are programs that can reduce or eliminate toxic stress in the home. Eliminating that toxic stress can produce large benefits for children.

The term "toxic stress" was coined by a group called the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. It is led by Jack Shonkoff, at Harvard University, in his Center on the Developing Child.1 For about 15 years now, I've had the privilege of being the "token social scientist" among the neuroscientists in this network. Over the course of those years, most of the best work of the centre has been done by the neuroscientists, working with knowledge translators - including a firm called Frameworks, which is a messaging firm that works with social and behavioural scientist to try to get their messages across. Toxic stress was one of the first concepts they developed.

Unfortunately, the term has mutated into something that's almost unrecognisable now, so for the purposes of this discussion let's first consider what is and isn't toxic stress, and how important it is to eliminate true toxic stress.

The National Scientific Council has developed a taxonomy of stress: positive stress, tolerable stress and toxic stress. Positive stress is the good kind of stress - all children need to have healthy stress reactivity, brief increases in the heart rate and mild increases in stress hormone levels that are quickly restored to baseline levels. Tolerable stress might arise when the child experiences a serious event - the death of a relative, maybe a natural disaster of some sort. What makes the stress from these events tolerable is when a caregiver can provide comfort and support. With such caregivers, children can bring their stress responses back down to baseline levels.

What is unacceptable are situations of toxic stress, where prolonged activation of stress systems, in the absence of protective relationships, can damage lifelong health. What kinds of situations create toxic stress? Examples include recurrent physical and emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, and repeated exposure to violence. Thankfully, few children are exposed to these kinds of conditions, but when they are, the effects can be extremely damaging. Both animal experiments and natural experiments from adoption studies, from orphanages and the like, show how damaging toxic stress can be for children, and how important it is to address this problem.

The concept of "toxic stress" has morphed from its original definition into something that's almost unrecognisable. It's like what people do with preschool stress-reduction programs. Toxic stress is something that people evoke all the time now to justify any sort of parent- or child-directed program, saying: "Well, it returned $10 per dollar spent, therefore my program is going to produce $10 per dollar spent."

True toxic stress is grounded in neuroscience. It's vitally important, as we do our work, to recognise circumstances of toxic stress for children and to remediate that stress. So if I were to select the highest priority area for parenting programs seeking to provide second-generation benefits, it would be to address circumstances leading to true toxic stress. All countries need a national network of effective, well-resourced public programs to detect and remediate conditions that are likely to generate toxic stress in children.

I know that some people believe that home visitation programs are a solution to the problems of toxic stress, so I wanted to spend a little time talking about the evidence on home visitation programs. These are in various stages of rollout in Australia. A very good literature review was completed as part of a US project called Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HOMVEE).2 Mathematica, which is a high quality research firm in the United States, conducted a broad literature review of home visitation programs. They found evaluations of 35 different models, 14 of which rested on a sufficiently rigorous standard of evidence. Table 1 shows a subset of programs from the HOMVEE review. Nurse-Family Partnership is the David Olds model that everyone points to. It produced evidence of positive parenting practices four times across the evaluations that were published, five instances where child development and school readiness outcomes were significantly affected and seven instances where there was a reduction in child maltreatment.

| Positive parenting practices | Child development and school readiness | Reductions in child maltreatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse-Family Partnership | 4/22 | 5/59 | 7/25 |

| Parents as Teachers | 3/50 | 7/66 | 1/3 |

| Early Head Start- Home Visiting | 3/28 | 2/36 | Not measured |

| Early Start (New Zealand) | 3/3 | 2/6 | 1/12 |

| Family Check-Up For Children | 2/2 | 3/14 | Not measured |

| Family Spirit | 0/5 | 10/40 | Not measured |

| Healthy Families America | 2/50 | 9/43 | 1/34 |

| Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) | 1/10 | 3/20 | Not measured |

| Minding the Baby | 0/2 | Not measured | 0/1 |

But we need to know what the denominators are for these numbers. If you test 20 different outcomes and one of them shows up as being statistically significant at the 5% level, then that one estimate could be statistically significant completely by chance. As you can see from Table 1, there are some pretty big denominators. In the case of the positive parenting practices, 22 of them were tested and only four turned out to be statistically significant. Child development outcomes were identified in five out of 59 cases, and reductions in child maltreatment in seven out of 25. We need to pay attention to the numerators as well as the denominators. I know HIPPY is being rolled out pretty ambitiously here. In its evaluations, positive impacts on parenting practices were found in only one out of 10 impact estimates. Evidence on child maltreatment is sparse. In this case, the Olds & Kitzman (1993) study stands out as the only one that seems to show any real and substantial evidence that it reduces child maltreatment.

So if we think about home visitation as a way of reducing toxic stress, the evidence base is very thin. I hope that I can inspire people involved in some of these evaluations to consider the range of outcomes, including child maltreatment, that you might want to include. We're still a long way off from being able to point with confidence to program models or home visitation that will work in all communities. This HOMVEE effort preceded a very ambitious evaluation of a number of home visitation models.

Conclusion

Let me return to my opening question, which asked whether one plus one is greater than two. I want to try to end on a positive note, and return to the Danish study. Using administrative data, researchers were able to discover that two kinds of programs - home visitation and early education - produced quite positive impacts. Children growing up in municipalities with early education programs completed more schooling, earned more, were healthier and bore children who attained more schooling. So having good early education programming can make a big difference. And some of these same benefits were enjoyed by children in the municipalities with the home visitation program. Although second-generation outcomes did not prove to be more positive, a number of first-generation outcomes turned out to be more positive years later.

So even though their combination wasn't synergistic, each program by itself was quite effective. We can be encouraged by the fact that our countries have programs that actually work - if you think about K-12 schooling, we complain about it all the time, but it's really been the engine that has fuelled a lot of our economic growth. Our child protective service systems are far from perfect, but they are helping large numbers of children who very much need the help.

We're in a good position now. We've got some promising program models and we are putting administrative data systems in place that will assist in their evaluation. So we're in a much stronger position to implement and improve and evaluate the kinds of programs that we desperately need to help our young children and their families. Let's get to work!

Useful resources

Restoring Opportunity (Duncan & Murnane, 2014) looks at the kinds of practices that schools are engaging in that seem to make a difference in terms of bringing up the scores of low SES children. On the book's website, <RestoringOpportunity.com>, we present three six-minute videos featuring a preschool, a charter school3 and a high school, which the evidence shows to be producing good results with low-SES children. The videos demonstrate the kinds of practices that these schools are engaging in that seem to make the difference.

Future of Children <www.futureofchildren.org/> is a free online journal published by Princeton University and the Brookings Institution. It does a very good job of focusing on various topics related to children and child policy. In the issue on two-generation programs, Chase-Lansdale and Brooks-Gunn summarise the existing evidence on these programs and identify promising future directions.

The Center on the Developing Child <www.developingchild.harvard.edu> is a great resource with animations that explain brain architecture <developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/brain-architecture/>, the concept of serve and return <developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/serve-and-return/>, toxic stress <developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/>, and executive function <developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/executive-function/>. One of its reports called From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts <developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/from-best-practices-to-breakthrough-impacts/> provides an accessible review of the science of early development and a summary of some of the intervention research from this meta-analysis, as well as ideas about dynamic strategies for generating programs. From the ground up, states or cities are developing programs and then sharing and evaluating them, in a way that is true to the science, but also provides the kind of evaluation evidence that we really need to determine whether these programs are working or not.

Jack Shonkoff's Center on the Developing Child is developing measures of toxic stress in children, which will probably be available within a year. This will be very important. How can you measure stress reactivity in children in a way that allows you to judge whether or not they are suffering from toxic stress?

A National Academy of Sciences report called Supporting the parents of young children (see <www.nap.edu/catalog/21868/parenting-matters-supporting-parents-of-children-ages-0-8>) provides a comprehensive review of universal programs for supporting parents, as well as more specialised programs geared to specific needs - drug abuse, mental health problems, etc. - along with programs addressing the special needs of children in different categories. All of these National Academy reports are available online, so it's another free resource.

Endnotes

1 See <www.developingchild.harvard.edu>.

2 For HOMVEE's activities see <homvee.acf.hhs.gov>.

3 A school that receives government funding but that operates independently of the established public school system in which it is located.

References

- Bradbury, B., Corak, M., Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2015). Too Many Children Left Behind: The US Achievement Gap in Comparative Perspective. NY: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

- Chase-Lansdale, P. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2014). "Two-Generation Programs in the 21st Century", Future of Children, 24(1), 13-39.

- Duncan, G. J., & Murnane, R. J. (2011). Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children's life chances. NY: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

- Duncan, G. J., & Murnane, R. J. (2014). Restoring opportunity: The crisis of inequality and the challenge for American Education. Cambridge, MA, & New York, NY: Harvard Education Press & Russell Sage Foundation.

- Grindal, T., Bowne, J. B., Yoshikawa, H., Schindler, H. S., Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2016). The added impact of parenting education in early childhood education programs: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 238-249.

- Olds, D.L., & Kitzman, H. (1993). Review of research on home visiting for pregnant women and parents of young children. Future of Children, 3(3), 53-92.

- Rossin-Slater, M., & Wüst, M. (2016). What is the added value of preschool? Long-term impacts and interactions with a health intervention (NBER Working Paper No. 22700). Washington DC: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from <www.nber.org/papers/w22700.pdf>.

Greg Duncan is Distinguished Professor in the School of Education at the University of California, Irvine. This article is based on the keynote address given by Greg Duncan at the 16th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference: Research to results - Using evidence to improve outcomes for families, Melbourne, 6 July 2016.