The nature and extent of sexual assault and abuse in Australia

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2012

Antonia Quadara

Download Practice guide

This ACSSA Resource Sheet summarises the available statistical information about the nature and extent of sexual assault and abuse in Australia. It draws on Australian data sources, and provides information on the prevalence of sexual violence as well as characteristics of victimisation and perpetration. Because sexual assault and abuse are significantly under-reported this Resource Sheet describes the limitations associated with these collections. It also describes how we can use data that examine sexual victimisation in high-risk populations.

Overview

Statistics carry significant power and persuasion. At one level they appear to provide an instant and accessible way of grasping the nature and extent of social issues. Yet any statistic has a complex methodological history, which affects how it can, and should, be used. This is important to remember when attempting to determine the extent of sexual assault. A range of factors such as barriers to disclosure, the low rate of reporting to police, varying definitions of sexual assault and abuse,1 and the complexity of recording and counting such information make this a particularly hidden type of violence. Understanding the types of statistics available and what they are measuring is therefore very important.

Sexual assault statistics are based on two main types of data:

- administrative data - data extracted through the various systems that respond to sexual assault (e.g., police, courts, corrections or support services); and

- victimisation survey data - data collated from surveys conducted with individuals, asking them about their experiences of sexual assault victimisation, regardless of whether they have reported to police.

While administrative data, such as recorded crime figures, provide an indication of the number of sexual assaults that are brought to the attention of the criminal justice system, it cannot provide a reliable estimate of the extent of sexual assault and abuse in the Australian community. It has a valuable but limited application in understanding prevalence.2 This is for two reasons:

- The majority of victim/survivors do not report their experiences of sexual assault to police - for example, figures from the Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2005 (Personal Safety Survey) show that more than 8 out of 10 female victims of sexual assault by a male perpetrator did not report the most recent incident3 of assault to police4 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2006a).

- There are inconsistencies in data collection both in terms of whether the information is recorded and in terms of how it is recorded and counted. This is the case across sectors (e.g., between police recording/counting practices and those used by the courts), and within the same system sectors but across jurisdictions.

Administrative data provide limited information about a small and discrete group of the population: those who report sexual assault to police. For example, the Recorded Crime - Victimsdata, referred to later in this paper, provides content on details such as characteristics of sexual assault, characteristics of victims, locations of assaults and the relationship between offender and victim. These data are collected primarily for law enforcement and administration of justice; that is, investigation and case management. Statistical (such as measuring crime victimisation rates and characteristics of victims) and management (such as informing resourcing) information are secondary uses of these data and thus the data do not inform the whole context in which these offences have taken place.

Victimisation survey data also have limitations:

- They may exclude vulnerable or hard-to-reach groups in the community.

- In-depth and detailed surveys are conducted infrequently, largely due to cost.

- There is great complexity involved in collating the data5 (e.g., respondents may omit incidents they do not consider relevant or are not comfortable reporting).

- Different measures are used across surveys and sometimes between one survey cycle and the next, meaning that data are not always comparable, even if the concepts asked about appear to be similar.

- Survey data are also subject to sampling variability6 (e.g., estimates based on the selected sample may differ from figures that would have been produced if all persons had been included in the survey).

While national surveys such as the Women's Safety Survey, Australia (ABS, 1996) and the Personal Safety Survey (ABS, 2006a) provide the most reliable information about the prevalence and extent of sexual assault in Australia, it is important to remember that the survey design excludes the experiences of the most vulnerable members of our community; for example, children and young people, very remotely situated Australians, prisoners, people in residential care and other institutional settings. These people are acknowledged in research and sexual assault literature as being at greater risk of sexual assault.

This resource sheet focuses on data collected from:

- Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2005 (victimisation survey data);

- Crime Victimisation Survey, Australia, 2010-2011 (victimisation survey data); and

- Recorded Crime-Victims, Australia, 2011 (administrative data).

While these publications present statistics about closely related concepts, it is important to be aware that survey and administrative data capture significantly different information and the data generated from these sources depict very different elements of sexual assault and abuse in the community.

The secrecy, shame, guilt and fear that surrounds sexual assault and abuse stymies disclosure and discussion, and presents complex ethical, moral and methodological issues for those researching the issue. To that end, there is no single data source that is able to provide all the information required to paint a detailed picture of the full extent of sexual assault and abuse in the Australian community. Rather, there are multiple sources of information that must be referred to in order to gain an understanding of the prevalence of this social harm.

Definitions of sexual assault and sexual abuse

In Australia, there is no uniform definition of "sexual assault". Legislative definitions (i.e., those contained in the criminal law) vary across jurisdictions (see Fileborn, 2011). Survey research typically uses behavioural rather than legal definitions, which can include a broad range of behaviours, such as:

- sexual harassment;

- sexualised bullying;

- unwanted kissing and sexual touching;

- sexual pressure and coercion; and

- sexual assault including rape.

The Personal Safety Survey uses the terms "sexual assault", "sexual threat", "sexual violence" and "sexual abuse", the ABS definitions for which are provided in Table 1. These definitions are consistent with those used in the Women's Safety Survey (ABS, 1996). The term "sexual assault" is also used in the Crime Victimisation Survey (ABS, 2012b) and the Recorded Crime - Victims (ABS, 2012a) data collection. These terms and definitions are based on descriptions of behaviours that would be considered offences under State and Territory criminal law (ABS, 2006c). As such, they reflect a relatively narrow band of behaviours within the spectrum of sexual violence.7

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

Sexual assault | Personal Safety Survey: An act of a sexual nature carried out against that person's will, through the use of physical force, intimidation or coercion. It includes rape (sexual penetration without consent), attempted rape, aggravated sexual assault (sexual assault with a weapon), indecent assault, penetration by objects and forced sexual activity that did not end in penetration. Unwanted sexual touching and incidents that occurred before the age of 15 are not included. Crime Victimisation Survey: Definition of sexual assault is based on the interpretation of the respondent. If requested, the definition provided is "an act of a sexual nature carried out against a person's will, through the use of physical force, intimidation or coercion, or the attempt to carry out these acts". Only people aged 18 years and over were asked questions about sexual assault. Recorded Crime - Victims (Definition is based on the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification [Cat. No. 1234.0]): Physical contact, or intent of contact, of a sexual nature directed toward another person where that person does not give consent, gives consent as a result of intimidation or deception, or consent is proscribed (i.e., the person is legally deemed incapable of giving consent because of youth, temporary/permanent [mental] incapacity or there is a familial relationship). |

Sexual threat | Personal Safety Survey: The threat of an act of a sexual nature carried out against a person's will through the use of physical force, intimidation or coercion. The person must have believed that the threats were able and likely to be carried out. It only includes threats made face-to-face, which may have been verbal, involved a weapon or threats to harm children. Unwanted sexual touching and incidents that occurred before the age of 15 are excluded. |

Sexual violence | Personal Safety Survey: Any incident of sexual assault or threat (defined above). |

| Sexual abuse | Personal Safety Survey: Involving a child (under the age of 15) in sexual activity beyond their understanding or contrary to currently accepted community standards. |

Data collections measuring sexual assault

Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2005

The Personal Safety Survey measures the nature and extent of women's and men's experiences of physical and sexual violence since the age of 15 and actions taken by, and impacts on, victims following these experiences. Conducted periodically by the ABS as part of its household survey program,8 respondents are asked a series of questions about their experience of sexual assault over their life course, their most recent experience of sexual assault, and whether they had experienced sexual assault in the previous 12 months. Questions included number of perpetrators, relationship between victim and perpetrator, location of incident, and whether the incident was reported to police.

However, there are some caveats to consider when interpreting and using the Personal Safety Survey data. Even prior to the collection of data, researchers investigating the incidence of sexual assault face barriers, such as reluctance of victims to disclose experiences of sexual assault due to cultural and/or religious taboos, shame, language difficulties, and individual definitions as to what types of acts constitute sexual violence.

Another caveat is that these data are primarily collected from people who live in private dwellings. Therefore, the data do not reflect the experiences of the homeless, or those in supported accommodation or residential units, institutional settings such as prisons or nursing homes, student accommodation or crisis accommodation. The ABS also notes in the survey design that people living in very remote areas, who would have been included in the scope of the survey, were excluded.9 From what is understood in the literature about the incidence of sexual assault, this means that the experiences of those people in our community most at risk of sexual assault victimisation are excluded.

Most significantly it is particularly important to be aware of the issue of under-reporting when discussing statistical representation of the nature and extent of sexual violence in the Australian community.

Consequently, while the Personal Safety Survey provides the most authoritative, cross-sectional national data on the prevalence of sexual violence, smaller, qualitative surveys and case studies are equally important when examining and understanding the cultural and social narratives of this form of violence. However, for a more in-depth discussion of prevalence rates of sexual assault and abuse within these high-risk sectors, readers are encouraged to refer to the cited publications throughout the "Sexual victimisation in high-risk populations" section of this paper.

The most regular statistical information about sexual assault incidents experienced by both men and women in Australia is found in the annual Crime Victimisation Survey. Statistics on the number of sexual assaults reported or detected by a policing agency are found in the Recorded Crime - Victims data. Both of these are discussed in the following sections.

The Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2005

- The survey is conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the official national statistical agency. It follows on from the Women's Safety Survey (ABS, 1996). The 2005 survey included the experiences of men.

- In 2005 it surveyed 11,800 women and 4,500 men about their experiences of incidents such as physical assault, stalking, sexual harassment, sexual assault and partner violence.

- National population estimates are derived from this (see Morrison, 2006).

- Interviews were conducted face-to-face except where individuals requested a telephone interview.

- It is accompanied by a User Guide to enable appropriate use and interpretation of findings (ABS, 2006c).

Crime Victimisation Survey, Australia, 2010-2011

The Crime Victimisation Survey, Australia, 2010-2011 (ABS, 2012b) data form a component of the ABS Multipurpose Household Survey. Only two questions pertaining to sexual assault were asked at the end of this module:

- whether the respondent has been a victim of sexual assault or attempted sexual assault in the 12 months prior to interview; and

- whether a victim told the police about the most recent incident (ABS, 2012b).

The 2010-11 survey estimated that 54,900 (0.3%) of Australians aged 18 years and over were the victims of at least one sexual assault in the previous 12 months prior to interview (ABS, 2012b). The findings are based on victimisation survey data and provide a summary of people's experiences of certain criminal offences. They also examine the characteristics of victims, the characteristics of their most recent incident (in the last 12 months) and whether they reported the incident to police.

A key difference between the Crime Victimisation Survey and the Personal Safety Survey is the method of data collection. The Personal Safety Survey collected more detailed data for sexual assault offences by conducting face-to-face interviews with a majority of respondents, whereas the Crime Victimisation Survey was conducted over the phone, as part of a broader survey about households. (For further comparison see ABS, 2011.)

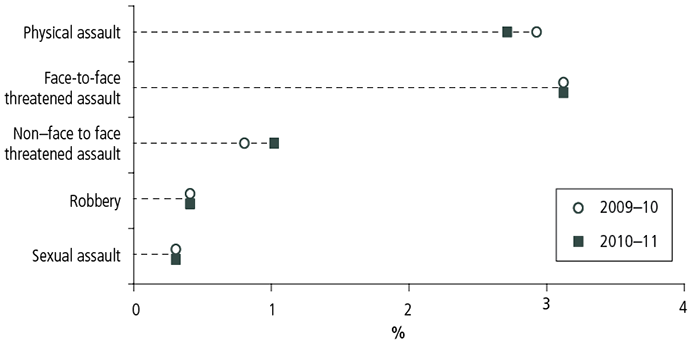

Figure 1: Personal crime victimisation rates, by type of crime, 2010-2011 compared to 2009-2010, according to Crime Victimisation Survey

Source: ABS, 2012b

Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia 2011

The statistics arising from the publication of Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2011 (ABS, 2012a) are based on administrative data. They represent information for a selected range of offences recorded by police during 2011. These figures do not represent the total number of victims or the total number of individual offences that come to the attention of police because of the counting methodology employed (see "Explanatory notes - Counting methodology" in ABS, 2012a.)

The Recorded Crime - Victims data are based on a different reference period than that measured in the Personal Safety Survey. The administrative data are collated from reports to police about victims' experiences of sexual assault, but do not differentiate between recent or historical incidents of sexual assault. That is, victims who reported an incident of sexual assault to police in the past 12 months may have experienced sexual abuse as a child and only recently reported the matter.

The data showed that, for 2011, 85% of victims who reported sexual assault to police were female, and 50% of these incidents took place in a private residence. New South Wales had the highest rate of sexual assault reported to police, with 6,001 victims recorded; followed by Queensland, with 3,896; and Victoria, with 3,784 (ABS, 2012a).

The data are not an indicator of prevalence of sexual assault in the Australian community, but rather reflect characteristics of victims and incidents where the sexual assault was reported to and recorded by police. As these data are reported annually, they do provide a useful indicator of changes in the rate of reported victimisation, and characteristics of victims or incidents over time.

Figure 2: Total number of sexual assaults reported to police, and broken down by gender, according to Recorded Crime—Victims data, 2011

Notes: WA data cannot be disaggregated by gender due to collection methods. Data for male victims in the NT, Tas. and ACT is 20, 25 and 24 victims respectively. These numbers are so small that they are barely visible on the graph.

The proportion of people who have experienced sexual assault

Many Australians are survivors of sexual assault. An estimated 1.3 million women and 362,400 men experienced an incident of sexual assault since the age of 15, according to results from the Personal Safety Survey 2005 (ABS, 2006a). This approximately translates to 1 in 6 women and 1 in 20 men.

In the 12-month period prior to interview, 1.3% of women and 0.6% of men experienced sexual assault.

In Tables 2A & 2B, total numbers of victims of sexual violence from the Women's Safety Survey are included as a comparison to the results from the Personal Safety Survey 2005.

| Personal Safety Survey 2005 | Total sexual violence, Women's Safety Survey 1996 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual assault | Sexual threat | Total sexual violence | ||

| Women | 1,293,100 (16.8%) | 353,700 (4.6%) | 1,469,500 (19.1%) | 1,228,400 (17.6%) |

| Men | 362,400 (4.8%) | 69,500 (0.9%) | 408,100 (5.5%) | NA |

| Personal Safety Survey 2005 | Total sexual violence, Women's Safety Survey 1996 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual assault | Sexual threat | Total sexual violence | ||

| Women | 101,600 (1.3%) | 34,900 (0.5%) | 126,100 (1.6%) | 133,100 (1.9%) |

| Men | 42,300 (0.6%) | 5,7001 (0.1%)* | 46,700 (0.6%) | NA |

* These figures are to be used with caution; estimate has a relative standard error of 25-50%.

Who are the victims of sexual assault?

Younger people are more likely that older people to report having experienced sexual assault:

- Of the women who experienced sexual assault in the 12 months prior to interview, more than half (57.4%) were aged under 35. More than a quarter (28.2%) of those women were aged 18-24 years.

- This differs slightly for male victims, with two-thirds aged under 35 (66.5%), and 32.6% of these respondents aged 18-24 years.10

A broad comparison made with the Recorded Crime - Victims police data for 2011 reported a similar national trend, identifying that females aged 15-19 had the highest victimisation rate for sexual assault (546 victims per 100,000). This rate is more than four times that of the overall female rate of sexual assault (129 victims per 100,000) (ABS, 2012a).

Child sexual abuse (before 15 years of age)

Almost 1 million women (956,600, or 12%) reported having experienced sexual abuse before the age of 15.11 More than 90% of victims knew the perpetrator (ABS, 2006a).

Of male respondents, 337,400 reported experiencing sexual abuse before the age of 15. Again, more than 80% of male victims knew the perpetrator.

Two thirds of all respondents (67.6%) reported being sexually abused before the age of 11.

Both males and females reported experiencing sexual abuse as a child by someone known to them. However, during their life course women were more likely to have reported being sexually abused by family members:

- Fathers, step-fathers and other male relatives (including siblings) made up more than half (51.6%) of perpetrators for females, and approximately one-fifth (21.4%) of perpetrators against males.

- Similar proportions of females and males were sexually abused by a family friend (16.5% and 15.6%, respectively) or an acquaintance/neighbour (15.4% and 16.2%, respectively).

- However, nearly 1 in 5 males under the age of 15 were sexually abused by a stranger (18.3%), compared to less than 1 in 10 females aged under 15 years (8.6%).

The continuum of sexual violence

It is important to place sexual assault within a broader context of sexual harassment and violence experienced by members of the community in everyday life. Harassment includes obscene phone calls, indecent exposure, inappropriate comments about a person's body or sex life, and unwanted sexual touching. The Personal Safety Survey 2005 showed that, since the age of 15:

- 32.5% (1 in 3) of women and 11.7% (1 in 8) of men had experienced inappropriate comments about their body or sex life;

- 1.9 million (approximately 25%) of women and 737,000 (10%) of men experienced unwanted sexual touching;

- 1 in 3 (31.5%) women and 1 in 7 (13.7%) men experienced obscene phone calls;

- 23.6% of women and 8.6% of men experienced indecent exposure; and

- 19.1% of women and 9.1% of men had been stalked. Two-thirds of all victims were stalked by someone known to them (ABS, 2006a).

Perpetrators of sexual violence

A greater proportion of women than men report experiencing sexual violence (i.e., assault and threat of sexual assault) in the context of intimate partner relationships (ABS, 2006a).

- Almost 1 in 5 (19%)12 of women reported that their most recent incident of sexual violence, since the age of 15, was perpetrated by a current partner.

- 28% of women and 6% of men13 reported that their most recent incident of sexual violence, since the age of 15, was perpetrated by a previous partner.

Differences in "known perpetrator" relationships

In the majority of reported cases of sexual assault, the perpetrator is someone known to the victim/survivor (ABS, 2006a). According to the Personal Safety Survey, there are notable differences in the experiences of women and men when comparing the relationship categories of the perpetrator to the victim/survivor. For example, men are more likely to be sexually assaulted by a stranger, but much less likely to be sexually assaulted by a previous or current partner; while women are almost 6 times more likely than men to report being assaulted by a family member or friend.

Using population estimates based on the Personal Safety Survey, in the most recent incident since age 15:

- "family or friends" is the largest category of known perpetrators against women;

- 643,000 women reported assaults by perpetrators in this category compared to 110,300 men;

- 161, 900 men reported sexual assault "other known persons";14 and

- 13 times more women than men15 were sexually assaulted by a previous partner.

If a broad comparison is made between the Personal Safety Survey and Recorded Crime - Victims data sets, it is possible to identify similar trends. For example, when looking at the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator, with the exception of the Northern Territory, family members are more likely to be the perpetrators of sexual assault than strangers. This pattern is also consistent with trends found in the Crime Victimisation Survey. Note that these differences are more pronounced when gender is disaggregated across these data sources.

Figure 3: Broad trends across data sources showing relationship of perpetrator to victim

Violence in intimate partner relationships

A module dedicated to partner violence in the Personal Safety Survey asked men and women about their experiences of violence perpetrated by current and/or previous partners.16 It showed that women are more likely to experience intimate partner violence compared to men (ABS, 2006a)17. In the context of sexual violence in intimate partner relationships, the following was found:

- A total of 27,400 (2.1%) women reported experiencing sexual assault by their current partner at the time of the survey.

- More than a quarter of a million women (272,300, or 24%) reported having been sexually assaulted by a previous partner since the age of 15.

- While no data are available on men's reports of experiencing sexual violence by a current partner since the age of 15, an estimated 20,700 (5.7%)18 of men would have reported experiencing sexual assault by a previous partner since the age of 15.

Sexual victimisation in high-risk populations

As previously mentioned, the most vulnerable and socially disadvantaged members of our community are often those who are the most difficult to consult. Research has identified that these cohorts are at higher risk of experiencing sexual assault and abuse than other sections of the community. We must therefore rely on more targeted research tools, which are smaller in scale, to capture the experiences of particularly vulnerable populations.

This section contains information about sexual victimisation against adolescents, Indigenous Australians, people with a disability, older Australians, and men and women in correctional settings.

Adolescents

The Personal Safety Survey showed that nearly 1.3 million Australian women and men reported an experience of sexual abuse before the age of 15 (ABS, 2006a, Table 29, p. 42). Young people's experiences of sexual abuse and sexual assault involves perpetration by those in positions of authority (e.g., clergy), guardianship (including family members) and care (e.g., sports coach, foster parent), as well as in relationship contexts and peer-to-peer social contexts. However, it is difficult to develop a robust statistical picture about the extent of sexual abuse and sexual assault this cohort experiences due to the limited research in this area, given ethical considerations (e.g., a young person's capacity to leave an abusive environment if a disclosure is made) and differences in methodology.

Other available studies have found the following:

- In a study on young people and domestic violence, 14% of surveyed women aged 12-20 had been sexually assaulted by a boyfriend (National Crime Prevention, 2001).

- A nationally representative sample19 of secondary school students found that 28% of young women and 23% of young men had had unwanted sex20 (Smith, Agius, Dyson, Mitchell, & Pitts, 2003).

- Australian females aged 15-19 had the highest victimisation rate for sexual assault (546 per 100,000) (ABS, 2012a).

Indigenous people

While there remains a paucity of reliable, comparative statistical data across states and territories, various surveys and police statistics generally confirm higher rates of sexual violence committed against Indigenous women compared to women in the non-Indigenous population.

- The Recorded Crime - Victims data relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders shows:

- In NSW, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were victims of sexual assault 3.5 times the rate of non-Indigenous persons.

- In Qld and SA, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were victims of sexual assault 4 times the rate of non-Indigenous persons.

- In the NT, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were victims of sexual assault at almost 2 times the rate of non-Indigenous persons.

- Elsewhere:

- The Australian component of the International Violence Against Women Survey found that Indigenous women reported experiencing higher levels of all kinds of violence, with three times as many Indigenous women compared to non-Indigenous women reporting sexual violence in the 12 months prior to the survey (Mouzos & Makkai, 2004).

- Sexual abuse notifications against Indigenous children are substantiated at a rate of five times that of non-Indigenous children (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2012, Tables A1.34 and A1.7).

- In a review of the international literature on Indigenous prevalence rates of sexual assault, Lievore (2003) stated:

… anecdotal evidence, case studies and submissions to inquiries support the assumption that sexual violence in Indigenous communities occurs at rates that far exceed those for non-Indigenous Australians. (p. 56)

Figure 4: Number of reported/detected victims of sexual assault by state, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, 2011

Source: ABS, 2012a

Note: Data for Indigenous populations in the other states/territories is not of sufficient quality for national reporting (ABS, 2012a).

Women and men with disability

Almost one in five (18.5%, 4 million)21 Australians report having disability (ABS, 2009). Studies show that adults with intellectual disabilities, psychiatric disabilities or complex communication disabilities are highly vulnerable to sexual assault (Murray & Powell, 2008). However, "there is no standard national data collection that includes the experiences of sexual violence amongst adults with a disability" (Murray & Powell, 2008, p. 3), which makes it very difficult to establish reliable prevalence data depicting sexual assault within this cohort.

The studies that offer a statistical insight into incidence of sexual assault among people with disability can provide indications of prevalence from which to work:

- Women with intellectual disability are 50-90% more likely to be subjected to a sexual assault than women in the general population (Howe, 2000).

- Victoria Police data from 2007 regarding sexual assault indicated that just over a quarter of all victims were identified as having disability. Of this group, 130 (15.6%) had psychiatric disability or a mental health issue and 49 (5.9%) had intellectual disability (Heenan & Murray, 2006).

It can be inferred from these data that adults with psychiatric and/or intellectual disability in particular were over-represented as victims of reported sexual assault, as adults with these categories of disability represent just 2.2% and 0.8% (AIHW, 2006) of the Australian population generally (Murray & Powell, 2008).

For an in-depth discussion of this topic see Murray and Powell (2008).

Older women and men

Older women continue to experience violence and abuse at higher rates than older men.

In one study, sexual assault against women in the 55-87 year old age group (mean age: 65) shared many characteristics with assaults against women in the younger age groups (see Quadara, 2007). Women in the older age group:

- were just as likely to experience severe methods of coercion, such as physical violence and restraint, as women in the two younger groups used in the study;

- were just as likely to be assaulted by an acquaintance as by a stranger; and

- sustained similar injuries to those sustained in younger age groups - including soft tissue damage (e.g., bruises) and lacerations - but sustained slightly higher rates of vaginal injuries than younger women.

Women and men in correctional settings

Prisoners are generally excluded from population surveys and to date most research conducted within correctional settings is not comparative with other jurisdictions.

Research suggests that men and women in correctional settings have histories of sexual victimisation, and studies in Australia and internationally identify that sexual assault occurs within these institutions (Clark & Fileborn, 2011; Heilpern, 1998; Kilroy, 2000; Richters et al., 2008).

A survey of 199 female prisoners and 1,118 male prisoners from NSW found that:

- 59% of women and 14% of men reported having been forced or frightened into doing something sexually that they did not want to do in their lifetime - rates higher than reported in the general community (21% women and 5% for men);

- 77% of men and 57% of women in the sample did not tell anyone or seek help following the incident/s; and

- revictimisation among this population was common: a third of women (32%) and a quarter of men (25%) said they had experienced sexual coercion between 3 and 9 times, and a further 13% of both men and women said it had occurred more than 10 times (Richters et al., 2008; see also Mazerolle, Legosz, Jeffries, & Teague, 2007).

Conclusion

All forms of research and administrative data have limitations in what they can tell us about an issue. These stem from methodological choices, the material constraints on undertaking research (e.g., time and money), and the complexity of the issue that is being investigated. Interpersonal violence, and particularly sexual assault and intimate partner violence, are all live issues.

There are challenges in conducting large-scale surveys in ways that are ethically and methodologically appropriate. It is also particularly challenging to collect data from vulnerable groups in our community; however, we know that it is precisely such populations that are most likely to experience sexual victimisation.

While the Personal Safety Survey 2005 contains the most in-depth national data and is unique as a source of information about lifetime prevalence in the Australian population, it is important to note that surveys such as this are designed to produce information that can be generalised to the Australian population. It is generally accepted in sexual assault research that undercounting is much greater than over-counting (ABS, 2004, pp. 8-9). Therefore, any statistical data available are likely to be an underestimation (Lievore, 2003).

Glossary

Incident: An occurrence/reoccurrence or event of violence, abuse or assault that an individual has encountered in their life (ABS, 2006c). The ABS states, “Where a person was a victim of continuous acts of violence by the same perpetrator (e.g., in a domestic violence situation), they may have considered the continuous acts of violence to be a single incident. In these cases, the person was instructed to think about the most recent act of violence by that perpetrator when answering the questions.”

Incident counts are commonly reported in ABS collections. A person can have multiple incidents of the same offence type; each occasion will be counted on an incident-based measure.

Prevalence: The proportion of people in a given population who have experienced sexual assault. Prevalence figures may relate to current levels of assault (e.g., when questions are asked about incidents in the previous 12 months) or it may relate to people’s experiences of sexual assault over particular periods (e.g., in the previous 5 years, or since the age of 15) (ABS, 2006c).

Prevalence rates can inform understandings of the likelihood of victimisation and reflect the number of discrete person victims of each offence type. The number of victims does not always equate to the number of incidents because, for example, one person may have experienced multiple incidents of the same type of offence.

Representative sample: A sample considered typical of, or representative of, a particular population. For example, in the case of a national survey, the representative sample is considered to be typical of the Australian population (ABS, 2006c).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1996). Women's Safety Survey, Australia (Cat. No. 4128.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2004). Sexual assault in Australia: A statistical overview. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006a). Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2005 (Cat. No. 4906.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006c). Personal safety survey: User guide. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). Australian Social Trends 2007, Women's experience of partner violence (Cat. No. 4102.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2009). Disability, Australia, 2009. (Cat. No. 4446.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011). Measuring Victims of Crime: A Guide to Using Administrative and Survey Data, June 2011 (Cat. No. 4500.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012a). Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2011 (Cat. No. 4510.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012b). Crime Victimisation, Australia, 2010-2011 (Cat. No. 4530.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2006). Family violence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from <www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10372>.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2012). Child Protection Australia 2010-2011 (Child Welfare Series No. 53, Cat. No. CWS 41). Canberra: AIHW.

- Clark, H., & Fileborn, B. (2011). Responding to women's experiences of sexual assault in institutional and care settings (ACSSA Wrap 10). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Fileborn, B. (2011). Sexual assault laws in Australia (ACSSA Resource Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Heenan, M., & Murrary, S. (2006). Study of reported rapes in Victoria 2000-2003: Summary research report. Melbourne: Office of Women's Policy, Department for Victorian Communities.

- Heilpern, D. (1998). Fear or Favour: Sexual Assault of Young Prisoners. Sydney: Southern Cross University Press.

- Howe, K. (2000). Violence Against Women With Disabilities - An overview of the literature. Rosney Park, Tasmania: Women With Disabilities Australia (WWDA). Retrieved from <www.wwda.org.au/keran.htm>.

- Kilroy, D. (2000, October). When will you see the real us? Women in prison. Paper presented at the Women in Correction: Staff and Clients Conference. Convened by the Australian Institute of Criminology in conjunction with the Department of Correctional Services, Adelaide

- Lievore, D. (2003). Non-reporting and hidden recording of sexual assault: An international literature review. Canberra: Commonwealth Officer for the Status of Women.

- Mazerolle, P., Legosz, M., Jeffries, S., & Teague, R. (2007). Breaking the cycle: A study of victimisation and violence in the lives of non-custodial offenders. Brisbane: Crime and Misconduct Commission.

- Morrison, Z. (2006). Results of the Personal Safety Survey 2005. ACSSA Aware, 13.. Melbourne. Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Mouzos, J., & Makkai, T. (2004). International violence against women survey: Australian component. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Murray, S., & Powell, A. (2008). Sexual assault and adults with a disability: Enabling recognition, disclosure and a just response (ACSSA Issues Paper No. 9). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- National Crime Prevention. (2001). Young people and domestic violence: National research on young people's attitudes and experiences of domestic violence (Fact sheet). Canberra: Commonwealth Attorney-General's Department.

- National Statistical Service. (2012). Basic survey design (Chapter 6: Errors in statistical data). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from <www.nss.gov.au/nss/home.NSF/NSS/4354A8928428F834CA2571AB002479CE?opendocument>.

- Richters, J., Butler, T., Yap, L., Kirkwood, K., Grant, L., Schneider, A. M. A., et al. (2008). Sexual health and behaviour of New South Wales prisoners. Sydney: University of New South Wales.

- Quadara, A (2007). Considering "elder abuse" and sexual assault. ACSSA Aware, 15. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Quadara, A. (2008). Responding to young people disclosing sexual assault: A resource for schools (ACSSA Wrap No. 6). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Smith, A., Agius, P., Dyson, S., Mitchell, A., & Pitts, M. (2003). Secondary students & sexual health 2002: Results of the 3rd national survey of Australian secondary students, HIV/AIDS and sexual health. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society.

1 The term "sexual assault" is generally understood to refer to non-consensual acts of sexual violence against an adult. The term sexual abuse is generally understood to refer to non-consensual acts of sexual violence against children that are beyond their understanding or contravene social mores.

2 See Glossary

3 See Glossary

4 This refers to men and women who have experienced sexual assault since the age of 15 (Table 2).

5 For example, non-sampling errors can introduce unquantifiable bias into the data, such as inconsistencies between respondents' interpretation of survey questions and definitions of sexual assault.

6 For an explanation of sampling and non-sampling errors, see National Statistical Service, 2012. <http://www.nss.gov.au/nss/home.NSF/NSS/4354A8928428F834CA2571AB002479CE?opendocument>

7 Some surveys, such as the Australian component of the International Violence Against Women Survey, use the term "sexual violence" to refer to all the aforementioned acts as well as sexual touching, which takes into account more behaviours than indecent assault (Mouzos & Makkai, 2004).

8 The first Personal Safety Survey was conducted in 2005 and was partly modelled on the Women's Safety Survey carried out in 1996. Fieldwork on the second Personal Safety Survey commenced in the first half of 2012, and findings from the data are expected to be released in the second half of 2013.

9 The Personal Safety Survey was conducted in rural and remote regions of Australia; however, it excluded approximately 120,000 people in very remote areas of Australia who would have otherwise been included in the scope of the survey (see "Explanatory Notes - Survey Design" in ABS, 2006a, p. 43).

10 These figures are to be used with caution; estimate has a relative standard error of greater than 50%. In the Personal Safety Survey, national data relating to males was not of sufficient quality for publication at some levels of disaggregation due to low prevalence and sample size, resulting in high standard error. A national figure is not available in the Recorded Crime - Victims data set. However, data from some state and territory jurisdictions was available for male victims of sexual assault.

11 These figures tell us how many women were victims of sexual abuse before the age of 15. What the data does not make explicit is whether respondents were sexually assaulted by more than one perpetrator, or whether they incurred multiple experiences of sexual abuse (see ABS, 2006a, Table 29, "Experience of Sexual Abuse, Before the age of 15 - Selected characteristics", p. 42).

12 See ABS, 2006a, Table 22. NB: No results are recorded for males/current partner in this table.

13 According to the ABS, this estimate has a relative standard error of 25%-50% and should be used with caution.

14 This includes acquaintance, neighbour, counsellor, psychologist or psychiatrist, ex-boyfriend or girlfriend, doctor, teacher, minister, priest or clergy member, and prison officer.

15 Again, the estimate for men in this table has a relative standard error of 25-50% and should be used with caution.

16 "Current partner" includes both married and de facto relationships. If the incident was perpetrated by a person the victim was dating, with whom they later partnered, the perpetrator was counted as a boyfriend/girlfriend or date. "Previous partner" also includes previous married and de facto relationships. It includes partners at the time of the incident from whom the respondent is now separated, and partners that a respondent was no longer living with at the time of the incident. In short, "current partner" refers only to those perpetrators the respondent was involved with at the time of the survey (ABS, 2007).

17 Overall, men experience higher rates of physical assault outside intimate relationships compared to women. In the Personal Safety Survey, almost three quarters (73.7%) of male victims reported experiencing physical assault by a stranger during the last 12 months and almost half (42.7%) were aged between 18 and 24 years (see ABS, 2006a, Tables 14 & 16, pp. 28 & 30).

18 The ABS advises that this estimate has a relative standard error of 25-50% and should be used with caution.

19 See Glossary

20 "Unwanted sex" is a broader term than "sexual assault" or "sexual violence" and is used to capture sex that is pressured, or the result of intoxication or coercion. Young people themselves rarely use the terms "sexual assault", "rape" or "sexual abuse" to describe unwanted sexual experiences and they can have difficulty naming an incident as sexual assault (see Quadara, 2008).

21 Of this population, 87% had a specific limitation or restriction that impaired their ability to communicate, care for themselves, and their mobility; or restricted their participation in schooling or the labour force.

At the time of writing Cindy Tarczon was a Research Officer and Antonia Quadara was the Manager of ACSSA at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The authors gratefully acknowledge expertise and advice of the ABS; in particular, Lisette Aarons, Lydia Rutter and Drazen Barosevic. We also thank Rebecca Jenkinson, Bianca Fileborn and Daryl Higgins for their feedback.

Tarczon, C., & Quadara, A. (2012). The nature and extent of sexual assault and abuse in Australia (ACSSA Resource Sheets). Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-922038-18-0