The role and efficacy of Independent Children's Lawyers

Findings from the AIFS Independent Children's Lawyer Study

October 2014

Download Family Matters article

Abstract

Independent Children's Lawyers (ICL) can be appointed to represent the best interests of children and young people in family law proceedings in Australia, helping to fulfil the rights of children to participate in proceedings relevant to their care. The Australian Institute of Family Studies recently undertook a study into the role, use and efficacy of these lawyers; in particular, to determine to what extent their involvement in family law proceedings improves outcomes for children. This article summarises the key findings from the study. The full findings were published in 2013 by the Attorney-General's Department.

The passage of the Family Law Legislation Amendment (Family Violence and Other Measures) Act 2011 (Cth) saw, for the first time, Australia's obligations as a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) acknowledged in the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (the FLA). The FLA s 60B(4) now provides that an additional object of Part VII of the FLA is to give effect to the UNCRC. The UNCRC provides for the right of children and young people to participate in proceedings relevant to their care (Article 9) and to make their views known in relevant judicial and administrative proceedings (Article 12). The appointment of an Independent Children's Lawyer (ICL) - a lawyer who represents the best interests of children and young people in family law proceedings - is a key means by which Australia can meet these obligations.

Subsequent to the introduction of significant changes to the Australian family law system in 2006, there has been a marked increase in the proportion of cases where the appointment of an ICL has been ordered, rising from approximately one-fifth of parenting applications in the family law courts in 2004-05 to about one-third of such applications in 2008-09 (Kaspiew et al., 2009, p. 309). Despite this increase in orders for ICL appointments, and concerns raised about the adequacy of funding for ICLs and variations in ICL practice throughout Australia, prior to the Independent Children's Lawyers Study: Final Report (Kaspiew et al., 2013) (the ICL Study), there had been a dearth of nationally based research investigating the nature and effectiveness of ICLs in the Australian family law context.

The ICL Study presents the findings of Australia's first mixed-methods research project examining the role, use and efficacy of ICLs in the family law system. The study was based on quantitative and qualitative data from ICLs, non-ICL lawyers, judicial officers and non-legal professionals, as well as from parents, children and young people who had been involved in proceedings where an ICL had been appointed. The research questions covered four broad themes: practices concerning the allocation and utilisation of ICLs; the role and responsibilities of ICLs; the effectiveness of ICLs; and whether improvements needed to be made to systems and processes in relation to ICLs. The central research question was: To what extent does having an ICL involved in family law proceedings improve outcomes for children?

Methodology

The findings presented in the ICL Study are based on a mixed-methods approach to data collection via four main studies:

- Study 1, the core quantitative study, comprised multidisciplinary, online surveys of ICLs (n = 149) and other professionals, including non-ICL legal practitioners (barristers and solicitors) (n = 192), non-legal family law system professionals (n = 113),1 and judicial officers (n = 54).2 The surveys also included open-ended questions aimed at collecting qualitative data on a range of aspects of ICL practice. These data provided an important means of examining the views of the main stakeholders on key aspects of, and expectations in relation to, ICL practice.

- Study 2 involved in-depth, semi-structured interviews with parents, children and young people who had been involved in a family law matter in which an ICL was appointed and which had been finalised in 2011 or 2012. Interviews focused on participants' experiences of the ICL in their case, and were conducted by phone (parents) and in person (children/young people). These data provided in-depth insight into the experiences of parents/carers (n = 24 from 23 parent/carer interviews) and children/young people (n = 10) in cases involving ICLs, which informed the analysis of ICL practices from the perspective of those who are directly affected by them.

- Study 3 involved in-depth, semi-structured interviews with ICLs (n = 20), and focused on substantive practice issues in relation to representing children and young people, procedural questions, the strengths and weaknesses of the ICL role as formulated in legislation, and the qualifications, accreditation and training needs of ICLs. ICLs were invited to express interest in participating in these interviews at the conclusion of the multidisciplinary survey and these interviews were conducted by telephone.

- Study 4 and 4a comprised an examination of the organisational context in which ICLs operate (in particular legal aid policy and practice in relation to ICLs) undertaken via a formal request for information (detailing policy, procedural and budget information), together with interviews with representatives from each state and territory legal aid commission. Interviews with child protection (CP) department representatives in each state and territory also provided information about arrangements for interaction between ICLs and these departments.

Organisational context and variations in policies and approaches

The ICL role was originally developed by the Family Court of Australia in case law3 and later codified in the FLA.4 The legislative provisions and case law, together with the Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers (National Legal Aid, 2013) reflect an expectation that ICLs will provide independent and impartial assistance to the court in determining the arrangements that are in the best interests of the child, rather than acting as the child's or young person's direct legal representative. Pursuant to s 68L of the FLA, courts exercising family law jurisdiction may make an order for the independent representation by a lawyer of a child's interests in the proceedings, being guided by the non-exhaustive criteria in Re K (1994) 17 Fam LR 537.5 When making such an order, the court will request that the relevant legal aid commission arrange for the appointment of the ICL. Legal aid commissions in each state and territory are responsible for accrediting ICLs and administering grants of legal aid to ICLs. At the time that the ICL Study was undertaken, across Australia, 361 ICLs were in private practice and 153 were inhouse legal aid lawyers.6 In 2009-10 and 2011-12, ICL grants totaled just over $65 million nationally (GST exclusive), averaging some $5,371 per grant. This compares with funding allocations of $263 million (GST exclusive) in the same period toward general family law grants (averaging $1,700 per grant).

Section 68LA of the FLA, together with the Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers, outlines the role of the ICL and provides that the ICL is a "best interests" representative rather than the child's legal representative (Guideline 4 and s 68LA(4)(a)), and is not obliged to act on the child's instructions (s 68LA(4)(b)). The ICL is required to "form an independent view, based on the evidence available" of the best interests of the child whose interests they are representing (s 68LA(2)(a)). The ICL can make submissions to the court suggesting the adoption of arrangements where the ICL is satisfied that these arrangements are in the best interests of the child (s 68LA(3)). The FLA also obligates the ICL to ensure that any views expressed by the child or young person about matters at issue are put before the court (s 68LA(5)(b)), although they are not under obligation and cannot be required to disclose to the court any information that the child or young person communicates to them (s 68LA(6)), save for the obligation on ICLs to notify a prescribed child welfare authority where they have reasonable grounds for suspecting child abuse or risk of child abuse (s 67ZA), and to file and serve the relevant Form 4 Notice when alleging child abuse or risk of child abuse or family violence or risk of family violence (s 67Z and s 67ZBA). The FLA also provides that the ICL may disclose information that the child or young person communicates to them if it is in the child's or young person's best interests to do so, even if the disclosure is against the child or young person's wishes (s 68LA(7) and s 68LA(8)).

The Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers provide further guidance about the expectations, limitations and operation of the ICL role, including the expectation nominated in Guideline 6.2 that the ICL will meet with the child or young person whose interests they are representing, unless:

- the child/young person is under school age; and/or

- there are exceptional circumstances, for example where there is an ongoing investigation of sexual abuse allegations and in the particular circumstances there is a risk of systems abuse for the child/young person; and/or

- there are significant practical limitations, for example geographic remoteness.

In addition, the Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers provide that the assessment about whether to meet the child (and the nature of that meeting) is a matter for the ICL (Guideline 6.2).

While the guidelines and the statutory framework operate across each state and territory,7 the ICL study data suggest that there existed substantial differences in policies among legal aid commissions. For example, legal aid commissions in some states limit appointments to cases where one (or more) of only two or three of the Re K criteria apply.8 Considerable variation in funding of ICLs also emerged across each state and territory.9

Other important areas of variation highlighted in our study include mechanisms for accrediting and monitoring the performance of ICLs. Each of the legal aid commissions requires lawyers to have completed the Independent Children's Lawyer training program, which is provided by the Family Law Section of the Law Council of Australia in conjunction with National Legal Aid, and expects ICLs to have a minimum five years of post-admission experience in the family law jurisdiction. However, data collected for Study 4 and 4a of the ICL Study, by way of a request for information and via interview respectively, indicate that each commission had their own selection process for appointments to the ICL panel. These data also indicate that there were no uniform professional development requirements for ICLs (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 103-104, 107-109).

Variations between commissions' policies in relation to meeting with children and young people also emerged (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 40-41). Some ICLs, particularly in Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia, adopt an approach in which this is seen as a collaborative function, with family consultants or single experts acting primarily as the conduit for ascertaining and interpreting children's and young people's views, facilitated by the ICL. An alternate approach involves consultation as part of the ICL's engagement with children and young people, and this may occur in parallel with the children and young people being seen by family consultants. These approaches to consulting with children and young people are considered in detail below.

ICL role and functions

The role of the ICL is multifaceted and may vary according to the particular circumstances of each case. The relevant FLA provisions, the Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers and data collected for this research suggest three overlapping functions in the ICL role:10

- facilitating the participation of the child or young person in the proceedings;

- evidence gathering; and

- litigation management - playing an "honest broker" role in:

- case management; and

- settlement negotiation.

Professionals surveyed for the ICL Study were asked to nominate the importance of each function. Table 1 indicates that from the perspective of participating ICLs, judicial officers and non-legal professionals, the evidence-gathering and litigation-management functions were identified as being of greater significance than the participation function. In our study, 55% of ICLs rated the participation function as significant or very significant, compared with 65% of judicial officers, 63% of non-ICL lawyers and 62% of non-legal professionals. Greater emphasis was placed by ICLs on the significance of their evidence-gathering function (83%) and litigation-management function (73%). Even higher ratings were recorded from participating judicial officers, with 94% identifying the evidence-gathering role and 83% describing the litigation-management function as being significant or very significant. The ICL's role in facilitating agreement was also very highly rated by ICLs and non-ICL professionals, with 81% of ICLs, 91% of judicial officers, 82% of non-ICL lawyers and 87% of non-legal professionals identifying this aspect of the ICL role as significant or very significant.

| ICL function | ICLs | Judicial officers | Non-ICL lawyers | Non-legal professionals | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant (%) | Very significant (%) | Total (%) | Significant (%) | Very significant (%) | Total (%) | Significant (%) | Very significant (%) | Total (%) | Significant (%) | Very significant (%) | Total (%) | |

| Participation function Facilitate children's/young people's participation in proceedings relevant to their care | 38.9 | 16.1 | 55.0 | 29.6 | 35.2 | 64.8 | 35.9 | 27.1 | 63.0 | 32.7 | 29.2 | 61.9 |

| Evidence-gathering function Assist court by gathering and testing evidence | 14.8 | 68.5 | 83.3 | 7.4 | 87.0 | 94.4 | 29.2 | 58.3 | 87.5 | 22.1 | 63.7 | 85.8 |

| Litigation management function A Assist court in management of litigation where parents are unrepresented | 22.8 | 49.7 | 72.5 | 24.1 | 59.3 | 83.4 | 29.2 | 48.4 | 77.6 | 24.8 | 42.5 | 67.3 |

| Litigation management function B Facilitate agreement in the best interests of the child/young person and avoid trial where possible | 31.5 | 49.0 | 80.5 | 16.7 | 74.1 | 90.8 | 31.3 | 50.5 | 81.8 | 29.2 | 57.5 | 86.7 |

| No. of respondents | 149 | 54 | 92 | 113 | ||||||||

Notes: Professionals were asked: "In your view, what aspects of the role of an ICL are very/less significant?" Percentages do not sum to 100% as not all response categories are presented. The proportion of "cannot say"/missing responses for the judicial officer, non-ICL lawyer and non-legal professional surveys ranged from 2.6% to 7.4% and for the ICL survey from 15.4% to 16.1%.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 2.7, p. 37)

ICL participation function: Main purposes and variability in practice

ICL practice approaches, particularly those relating to the function of supporting children's and young people's participation, emerged as the most contested and variable, with differences in approaches appearing to be driven both by different policies among some state and territory legal aid commissions and by different approaches adopted by ICL practitioners. A key area where ICL practice approaches differed related to their direct contact with children and young people.

When reflecting on their last three ICL cases, just over one-third (35%) of participating ICLs reported that they often or always had direct contact with the children or young people in their ICL cases, 54% reported that they engaged in such contact rarely or sometimes, and 8% reported that they never had direct contact with the children or young people in their ICL cases (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 49).11

While each of the legal aid commissions have endorsed the Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers, some commissions described additional, and in some instances differing, guidance to ICLs practising within their jurisdictions, including with respect to meeting with children and young people.12 When reflecting on their last three ICL cases, lower frequencies of direct contact with children and young people were reported by ICLs in Queensland (12%) and South Australia (27%) than by ICLs in Victoria (54%) and New South Wales (39%) (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 52). Notably, 82% of respondent ICLs in Queensland reported that they rarely (41%) or sometimes (41%) had contact with children and young people, and 27% of respondent ICLs in South Australia indicated that they never engaged in such contact (Kaspiew et al., 2013, Table 3.6).13

As Table 2 shows, when asked whether ICLs should have direct contact with the children and young people whose interests they represent, most non-ICL professionals indicated that ICLs should meet with the relevant child or young person in each case, although non-legal professionals were the group least likely to report a need for this contact to occur.

| ICL should contact | Judicial officers (%) | Non-ICL lawyers (%) | Non-legal professionals (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 68.5 | 67.7 | 63.7 |

| No | 25.9 | 25.5 | 29.2 |

| Not sure | 1.8 | 4.2 | 3.5 |

| Missing | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.5 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of responses | 54 | 192 | 113 |

Notes: Non-ICL professionals were asked: "Do you consider that ICLs should consult directly (in person or by telephone) with the relevant child or young person in each case where that child/young person is of sufficient maturity?" Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 3.3, p. 49)

Considerable variation emerged in relation to the main purposes of this direct contact between ICLs and the children and young people whose interests they represent. As Table 3 indicates, where direct contact did occur, this was most frequently undertaken to familiarise the child or young person with the ICL and their role (86%) and to explain the family law process (71%). Purposes associated with ascertaining children's and young people's views were less commonly nominated (60%). Lower still were the proportions of participating ICLs nominating purposes related to the explanation of court orders or process outcomes (51% and 56% respectively).

Table 3 also depicts differences arising in the context of the "community of practice" to which the ICL belongs,14 with ICLs who also practise in state/territory child protection matters reporting in greater proportions that they often or always engaged in direct contact to explain the ICL role (97%) or family law processes (81%) than their ICL colleagues practising in the family law jurisdiction alone. Of note, those ICLs also practising in state/territory child protection matters were likely to have represented children and young people on a direct instructions basis in the child protection jurisdiction.

| Reason for contact | ICLs who also represent children/young people in state CP matters (%) | ICLs who do not represent children/young people in state CP matters (%) | All ICLs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explain the ICL's role | 96.9 | 79.5 | 85.9 |

| Introduce the ICL | 93.8 | 81.9 | 85.9 |

| Explain the family law process | 81.2 | 65.1 | 71.2 |

| Explain the court orders that were made | 65.6 | 41.0 | 51.0 |

| Discuss the child's/young person's situation and ascertain their views | 63.3 | 59.0 | 59.7 |

| Explain the outcome of the family law process | 60.4 | 48.2 | 55.7 |

| No. of responses | 64 | 83 | 149 |

Notes: The following question was asked: "What is/are the main purpose(s) of your direct contact (in person or by telephone) with the relevant child or young person?" Data for two cases where CP representation status were not indicated are not included in the first two columns. The proportion of "cannot say"/missing responses ranged from 1.6% to 4.8%. Percentages do not sum to 100.0% as not all response categories are presented.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 3.4, p. 50)

Further insight is gained from the responses sought from each professional group with regard to the significance of various ICL participation tasks (see Table 4). The function of providing an independent view of orders that would be in the best interests of the child or young person was rated as being significant or very significant by 83% of ICLs, 93% of judicial officers, 88% of non-ICL lawyers and 94% of non-legal professionals. Responses relating to the significance of other participation functions, however, suggest a divergence between judicial expectations of ICLs and ICLs' conceptualisation of their role and their direct contact with children and young people. For example, 59% of ICLs rated the task of informing the child or young person of the nature of the proceedings and their options for involvement as being significant or very significant, compared with 78% of judicial officers reflecting on this function. Similarly, the ICL function of informing the child or young person of potential outcomes and seeking their feedback was rated as being significant or very significant by 56% of ICLs, as opposed to 74% of judicial officers, and informing children and young people of the outcomes of the process and the implications of court orders was identified as significant or very significant by 62% of ICLs, compared with 80% of judicial officers.

| ICL participation tasks | ICLs (%) | Judicial officers (%) | Non-ICL lawyers (%) | Non-legal professionals (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitate children's/young people's participation in proceedings relevant to their care | 55.0 | 64.8 | 63.0 | 61.9 |

| Provide the court with independent view on orders that would be in the best interests of the child/young person | 83.2 | 92.6 | 87.5 | 93.8 |

| Inform the child/young person of the nature of proceedings and options for their involvement | 59.3 | 77.8 | 69.8 | 63.7 |

| Inform the child/young person of potential outcomes and obtaining their feedback | 56.4 | 74.1 | 67.7 | 67.3 |

| Inform the child/young person of the outcomes and implications of court orders | 61.7 | 79.6 | 78.1 | 71.7 |

| Ensure focus in proceedings is on best interests of child | 80.5 | 94.5 | 85.5 | 95.6 |

| No. of respondents | 149 | 54 | 192 | 113 |

Notes: Professionals were asked: "In your view, what aspects of the role of an ICL are very/less significant?" Percentages do not sum to 100.0% as not all response categories are presented. The proportion of "cannot say"/missing responses for the judicial officer, non-ICL lawyer and non-legal professional surveys ranged from 2.6% to 7.4%, and for the ICL survey from 15.4% to 16.1%.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 3.1, p. 43)

Three important findings arose from the project data in relation to the ICL participation function.

First, the data establish that having direct contact with children and young people is not necessarily routine practice among ICLs. Both quantitative and qualitative data in this study suggest that the decisions ICLs made in relation to whether or when to engage in direct contact were informed by the age of the child or young person and the circumstances of the case (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 44). These decisions also reflected the practice orientation of the individual ICL and the policy and approach of the legal aid commission in which the ICL was based. The research identified two broad approaches to participation among ICLs. The dominant approach involved a cautious, multipronged approach to direct contact that focused on familiarisation between the ICL and the child or young person, and less frequently on the explanation of processes and outcomes (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 45-46). The second approach, involving a high level of direct contact, was less common. Here, all three purposes of direct contact were undertaken by the ICL: familiarisation, explanation and consultation with the child or young person regarding their views on outcomes (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 46-47). A key concern identified by ICLs who adopted a cautious orientation was that, as lawyers, they may lack the appropriate disciplinary training to consult with children and young people and to interpret their views. For these practitioners, their role was described in terms of the traditional best interests advocate who collates the necessary evidence and manages the litigation in a manner that is directed by their focus on the best interests of the child. Concerns were also raised about the ICL adding to the burden of the relevant child or young person, particularly in cases involving concerns about child abuse, where multiple professionals and agencies may already have engaged with them (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 45).

Second, these dominant and minority orientations to direct contact entailed a differing approach to the way in which the ICL and family consultant work together. While each approach relied on collaboration, the qualitative data suggest that ICLs adopting a cautious approach engaged in a greater level of sharing of responsibility for direct contact, necessitating a closer level of cooperative engagement between the family consultant/expert and the ICL (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 82-86). The quality of the collaboration between the ICL and the family consultant would be critical to the efficacy of the cautious approach to direct contact and the extent to which it reflects a coherent experience from the child or young person's perspective. Indeed, the significance and benefits of cooperation and collaboration between ICLs and family consultants/experts were clear themes emerging in the quantitative and qualitative data from both ICLs and non-legal professionals (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 81-89). However, the project data identified complex dynamics relating to accessible, effective and child-focused communication and consultation between ICLs and family consultants/experts, and to inter-professional understandings of responsibilities and role boundaries between these professionals, including uncertainty as to how the relationship should actually be managed (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 89-102).

Third, this research has highlighted a number of concerns about ICLs' practices relating to direct contact with children and young people. Quantitative data from judicial officers in particular indicate that current approaches to direct contact have not met their expectations (see Table 4). The divergence in expectations of the ICL participation function was even more pronounced in the interview data from parents and carers and from children and young people. From the perspective of the parents and carers interviewed, the approaches to direct contact employed in their cases generally meant that the professional who was representing the best interests of their children had limited or no personal contact with them (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 166). Disappointment with the extent and nature of direct contact by ICLs was even more pronounced in the data collected from interviews with children and young people. All of the children and young people interviewed had been involved in circumstances where their safety had been compromised, and they described expectations of the ICL listening to them, protecting them, advocating for them and helping them. For most of these children and young people, these expectations of the ICL were not met (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 166).

The lack of meaningful direct contact between ICLs and children and young people led to concerns among parents/carers and children/young people about the capacity of the ICL to understand their views and experiences and to, in turn, advocate for an outcome in their best interests. The accounts of children and young people, in particular, reflected disappointment with their limited (or no) contact with the ICL in their case, and indicated that often they were uncertain about what the ICL did and how their views informed the decision-making process and final outcome. While these parents/carers and children/young people focused on the ICL function of participation, the other ICL functions of evidence gathering and litigation management (that were most emphasised by ICLs and other professional respondents) appeared to have had little visibility for them (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 166).

Working with families at risk

The quantitative data illustrate that the ICL caseload is dominated by concerns about family violence and child abuse (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 32-33). ICLs and other stakeholders identified a clear need for a stronger focus on equipping ICLs to operate in this context, through initial training accreditation and ongoing professional development. This need was illustrated in the variation in the responses between ICLs and judicial officers regarding questions seeking assessments of the ICLs' ability to work with parents, children and young people in these contexts (see Table 5). For example, the ability of the ICLs to detect and respond to safety issues for children and young people, was identified as good or excellent by 69% of ICLs and 76% of judicial officers. In relation to detecting and responding to safety issues for parents, the variation between ICL and judicial officer reports was more pronounced, with 56% of ICLs nominating their ability as good or excellent, compared with 72% of judicial officers (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 118-120). A broader issue was also raised by the findings of this research regarding the system's ability to deal with complex cases, which almost always involve concerns about family violence (Kaspiew et al, 2013, p. 162).

| ICL tasks | ICLs (%) | Judicial officers (%) | Non-ICL lawyers (%) | Non-legal professionals (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identify issues of family violence and child abuse or neglect | 82.6 | 77.8 | 59.9 | 63.4 |

| Assess allegations of family violence and child abuse or neglect | 79.9 | 75.9 | 51.0 | 49.6 |

| Make referrals to the appropriate service for children/young people in cases involving family violence and child abuse or neglect | 76.5 | 66.7 | 40.6 | 41.6 |

| Work with children/young people who are at risk of experiencing family violence or child abuse or neglect | 59.7 | 53.7 | 25.0 | 35.6 |

| Identify circumstances where children/young people are at immediate risk of harm | 71.8 | 72.2 | 46.9 | 54.9 |

| Identify circumstances where child/parent/caregiver may be suicidal or at immediate risk of self-harm | 51.7 | 63.0 | 24.0 | 31.0 |

| Detect and respond to safety issues for parents | 55.7 | 72.2 | 30.2 | 32.7 |

| Detect and respond to safety issues for children/young people | 69.1 | 75.9 | 40.1 | 52.2 |

| Ensure that evidence regarding the child's/young person's developmental needs is gathered in the process | 77.7 | 75.9 | 55.2 | 56.6 |

| Ensure that evidence allowing the child's/young person's perspective to be understood is gathered in the process | 77.9 | 75.9 | 47.9 | 63.7 |

| No. of responses | 149 | 54 | 192 | 113 |

Note: ICLs were asked: "Please rate your ability to do the following in your work as an ICL". Non-ICL professionals were asked: "Please indicate your view, on average, of the ability of ICLs practising in your area to do the following". The proportion of "cannot say"/missing responses ranged from 16.1% to 22.1% in the ICL survey, 6.3% to 24.1% in the judicial officers and non-ICL lawyers surveys, and 12.4% to 25.7% in the non-legal professionals survey. Percentages do not sum to 100% as not all response categories are presented.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 7.3, p. 119)

ICL approaches to ensuring that the relevant children and young people were living in safe environments and to minimising the trauma of family law proceedings were also identified as falling short of the expectations of parents, children and young people. The accounts of many of these participants indicated that the professional practices that they experienced were insensitive to child safety concerns, and in some instances suggested an underlying assumption that no violence or abuse had occurred or that what did occur was not significant (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 162). Some of the parents interviewed also described the behaviour of professionals, including ICLs, as prolonging the resolution of the matter (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 167).

Practitioner quality and efficacy

The multidisciplinary surveys indicate that the ICL role is valued from the perspectives of most professionals, with questions about the effectiveness of ICL practice generally eliciting positive assessments from judicial officers and ICLs, with less positive assessments from non-ICL lawyers and non-legal professionals. The views of non-ICL professionals were sought in relation to whether the involvement of an ICL improves outcomes for children and young people (see Table 6). Responses indicate that judicial officers were the most positive group (89% agreeing or strongly agreeing) and non-ICL lawyers were the least positive (62% agreeing or strongly agreeing). On this question, the responses of non-legal professionals (83%) were closer to those of judicial officers than to those of non-ICL lawyers. Non-committal responses (i.e., "neither agree nor disagree") were provided by a larger proportion of non-ICL lawyers (20%) than judicial officers (4%) and non-legal professionals (5%) (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 118).

| ICL involvement improves outcomes for children/young people | Judicial officers (%) | Non-ICL lawyers (%) | Non-legal professionals (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agree/strongly agree | 88.9 | 61.5 | 83.2 |

| Neither agree or disagree | 3.7 | 19.8 | 5.3 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.9 | 11.5 | 1.8 |

| Cannot say/missing | 5.6 | 7.3 | 9.7 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of responses | 54 | 192 | 113 |

Notes: Non-ICL professionals were asked this question: "To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following proposition: Having an ICL involved in a case improves outcomes for children/young people." Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 7.2, p. 118).

The value attributed to the ICL role was also illustrated, for example, in the responses of the different professional groups to a question eliciting views about whether the present ICL model provides "sufficient opportunities" for the views of children and young people to be heard and considered in family law proceedings. Affirmative responses (i.e., strongly agree or agree), were provided by 80% and 76% of participating judicial officers and ICLs respectively, but by comparatively smaller proportions of the non-legal professionals (58%) and non-ICL lawyers (51%) (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 117).

Participants from all groups identified the relevance of concerns about practitioner quality to the question of the efficacy of ICLs (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 167). Importantly, perspectives on the question of how and in what circumstances ICLs did and did not contribute to better outcomes for children and young people emerged as being influenced by the way in which the various participants engaged with the family law system (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 163). For example, judicial officers identified the value of the ICL role as contributing an independent, impartial and child-focused perspective to the litigation-management and evidence-gathering process (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 164-165). Conversely, the level of dissatisfaction apparent from non-ICL lawyers, parents and children may be, in part, reflective of their experiences of the broader family law process, including the out-of-court events and negotiation phase (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 163-164).

The concerns relating to practitioner quality that were raised by stakeholders in each participant group covered two main areas:

- a lack of independence, impartiality and professional rigour in the way in which some ICLs discharge their obligations; and

- a failure to perform adequately and exercise a proactive and comprehensive approach in their role as ICL, including applying a thorough approach to gathering and analysing evidence (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 168).

More specifically, a clear theme emerging from the open-ended survey responses of each professional group was the variability of approaches and levels of competence among individual practitioners in the pool of ICLs (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 123-126). Several participants across the range of professional roles raised concerns about the incompetence and inactivity of some ICLs (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 127-135).

Systemic issues

Broader systemic issues were also identified by each participating professional group. These included issues associated with the adequacy of accreditation, training and ongoing professional development (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 105-107, 109-113, 135-140).

As Table 7 demonstrates, when asked about the adequacy of ICL training and qualifications, a significant proportion of non-ICL professionals considered the training and qualifications to be inadequate.

| Are the training and qualifications of ICLs adequate? | Judicial officers (%) | Non-ICL lawyers (%) | Non-legal professionals (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 27.8 | 26.6 | 19.5 |

| No | 40.7 | 40.6 | 31.0 |

| Not sure | 24.1 | 28.7 | 46.0 |

| Missing | 7.4 | 4.2 | 3.5 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of responses | 54 | 192 | 113 |

Notes: Professionals were asked: "Do you think the training and qualifications of ICLs are adequate?" Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 6.1, p. 109)

In relation to the ICL training and selection process, participants from all professional groups described the potential for improving the selection process (including selecting ICLs with social science qualifications and family law accreditation) in order to raise the level of expertise of ICLs appointed (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 105-109). The development of a national accreditation program, together with the expansion of ICL training to cover areas such as child development, skills in dealing directly with children and young people, and skills in understanding and responding to family violence and child abuse, were also identified as significant (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 105-106, 111-113). Measures for monitoring the performance and accountability of ICLs were also identified by some judicial officers, ICLs and non-ICL lawyers, with more structured programs for mentoring and peer support suggested by some participants (Kaspiew et al., 2013, pp. 113-114).

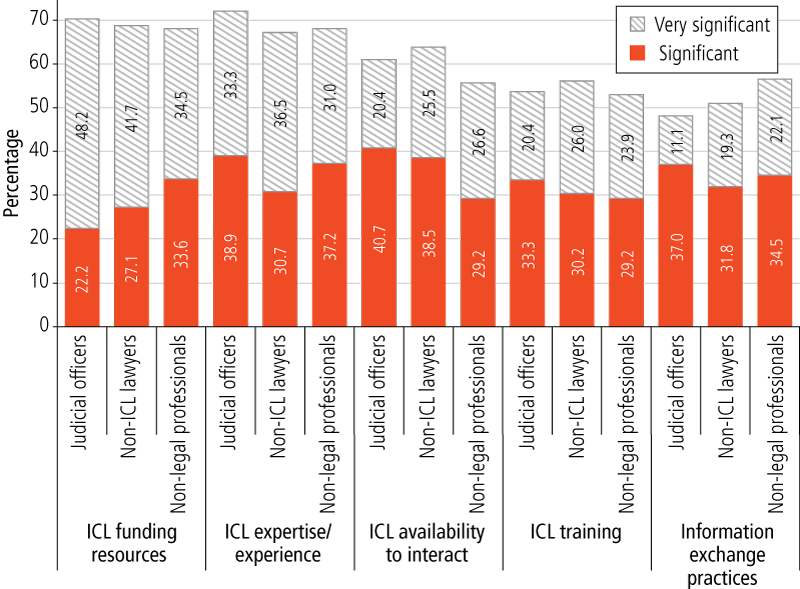

Underdeveloped practices and a lack of clarity about permissible inter-professional cooperation and collaborative practices also emerged as factors relevant to the efficacy of the ICL role. The development and establishment of relationships and processes that facilitate contact between ICLs and child protection department professionals were identified as uneven, with a variety of factors impeding this cooperation and collaboration, including availability, funding and practices around information exchange (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Non-ICL professionals rating ICL cooperative work practices as "significant" or "very significant"

Notes: Professionals were asked: "Thinking about cooperative work practices involving ICLs and other family law professionals, to what extent do the following factors impede effective interaction?" The proportion of "cannot say"/missing responses ranged from 5.2% to 18.5%.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Figure 5.1, p. 91)

Issues relating to the adequacy of funding were also identified as constraining the services that ICLs were able to deliver. The lack of funding available for the appointment of ICLs and the under-remuneration of ICLs for their work were identified as significant issues by participants in the professional groups, particularly in the responses of ICLs and judicial officers. For example, Table 8 demonstrates that 54% of ICLs and 70% of judicial officers considered the level of remuneration that ICLs receive to be inadequate as a reflection of the work that they are required to undertake.

| Does level of remuneration adequately reflect the work required of an ICL? | ICLs (%) | Judicial officers (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 10.1 | 1.9 |

| Somewhat | 12.8 | 13.0 |

| No | 54.4 | 70.4 |

| Not sure/missing | 22.8 | 14.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of responses | 149 | 54 |

Notes: ICLs and Judicial officers were asked: "Does the funding of the ICL program and/or the remuneration you received adequately reflect the work you/ICLs are required to undertake?" Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: Kaspiew et al. (2013, Table 7.4, p. 135)

More specifically, a greater proportion of ICLs directly employed by legal aid commissions regarded ICL remuneration to be adequate (23%) compared to ICL lawyers in private practice undertaking ICL work by appointment to the ICL panel (1%) (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 135). The research also found that panel ICLs were undertaking work that was required by their role on a pro bono basis due to the level of funding, in many cases provided via the lump sum grants of assistance for each stage of the proceedings (Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 136).

Conclusion

The ICL Study explored the role of ICLs in the family law system. The findings of this study were derived from a mixed-methods approach examining the central research question: To what extent does having an ICL involved in family law proceedings, improve outcomes for children?

The research found that considerable value is placed on the ICL role. Three overlapping aspects of the ICL role relating to participation, evidence gathering and litigation management were highlighted in the data, with professional participants placing greater emphasis on the evidence-gathering and litigation-management aspects of the ICL role, and parents, children and young people reporting the ICL's role in facilitating the child or young person's participation as being most significant. While many ICLs expressed concerns about having direct contact with children and young people - particularly in the context of child abuse concerns - the children and young people interviewed expressed disappointment with the limited or no contact they had with the ICL, as did their parents or carers. The responses from judicial officers also reflected an expectation of more contact between ICLs and the children and young people whose interests they represent. Further research examining what constitutes effective ICL practice from the perspective of children and young people is warranted, and more detailed consideration is required of how ICLs should engage with children and young people, even when child abuse concerns are pertinent. Research thoroughly examining the role of family consultants and single experts in the family law system generally, and in relation to direct contact with children and young people, in particular, would also be useful.

While the data suggest that the involvement of a competent ICL can contribute to better outcomes for children and young people, concerns were raised by all participant groups about ICL practitioner quality. ICL selection, training and accreditation, together with arrangements for monitoring ICL performance and facilitating their continuing professional development arrangements, were identified as areas for consideration. More broadly, further research is also required to consider how ICLs and other professionals can coordinate their consultations with children and young people and work collaboratively in the family law context to achieve outcomes in the best interests of children and young people.

Endnotes

1 The sample of non-legal professionals included family consultants/single experts, psychiatrists/psychologists and family relationship sector professionals, including mediation and family dispute resolution (FDR) professionals, and professionals working in children's contact services or post-separation support programs, such as parenting orders programs.

2 The sample of judicial officers included judicial officers and registrars of the Family Court of Australia, the Federal Magistrates Court of Australia (now known as the Federal Circuit Court of Australia) and the Family Court of Western Australia. Further details of the sample (including approach to recruitment) are available at section 1.3 of the ICL Study final report (Kaspiew et al., 2013). Note that references to page pinpoints cited in this article are from the first edition of this publication released on the Attorney-General's Department website on 22 November 2013 and were current at the time of writing.

3 See, for example, In the Matter of P v P (1995) 19 Fam LR 1; In the Marriage of Bennett v Bennett (1991) 17 Fam LR 561; DS v DS (2003) 32 Fam LR 352; and R v R: Children's Wishes (2000) 25 Fam LR 712. On the role of the ICL more recently, see: RCB as Litigation Guardian of EKV, CEV, CIV and LRV v The Honourable Justice Colin James Forrest, one of the Judges of the Family Court of Australia and Others [2012] HCA 47; State Central Authority v Best (No. 2) [2012] FamCA 511; State Central Authority v Young [2012] FamCA 843; Knibbs v Knibbs [2009] FamCA 840; McKinnon v McKinnon [2005] FMCAFam 516; T v S (2001) 28 Fam LR 342; and T v N (2003)31 Fam LR 257.

4 For current provisions, see the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) Division 10 - Independent representation of children's interests.

5 The criteria outlined in Re K (1994) 17 Fam LR 537 includes matters where there are allegations of sexual, physical or psychological abuse, allegations of antisocial conduct by one or both parents of a kind that seriously impinges on the child or young person's welfare (e.g., family violence), or where there is a relocation proposal that would restrict or, in practice, exclude, the other parent from having contact with the child/young person.

6 For further information about the number of inhouse ICLs (employed by a legal aid commission) and private panel ICLs (private practitioners appointed to the panel of ICLs) in each state and territory as at December 2012, and about the proportion of grants of assistance to ICLs, see Tables 2.1 and 2.2 of the ICL Study final report (Kaspiew et al., 2013).

7 Note, however, that Western Australia is governed by the Family Court Act 1997 (WA) and s 165 of that Act incorporates the provisions of s 68LA of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).

8 At the time of data collection for Study 4 of the ICL Study, ICL appointments were, for example, restricted in Victoria to matters falling within criteria 1, 3 and 7 of the non-exhaustive Re K criteria, and within criteria 1 and 6 in Western Australia. Criterion 1 relates to cases involving allegations of sexual, physical and psychological abuse; criterion 3 relates to cases where the child is apparently alienated from one or both parents; criterion 6 relates to alleged antisocial conduct by one or both parents (of a kind that "seriously impinges on the child's welfare", including family violence), and criterion 7 relates to instances of a significant medical, psychiatric or psychological illness or personality disorder affecting a parent, child/young person or another person with whom the child has significant contact.

9 See also Kaspiew et al. (2013), sections 2.2.3-2.2.5.

10 Note that Parkinson and Cashmore (2008) identified "a welfare role, a counsel assisting role and a role in giving the child a voice in the proceedings" (p. 51) and Ross (2012) referred to a counsel assisting role, a child participation role and a dispute resolution role (pp. 148-151).

11 Note that these responses were provided to the following question: "Thinking about the last three cases in which you have acted as an ICL, how frequently did you have direct contact (in person or on the telephone) with the child/young person. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding and because 2.7% of the 149 responses were missing.

12 For example, additional policy guidance provided by Legal Aid NSW indicate that all ICLs should meet with the children and young people whose interests they represent, and that depending upon the age of the child/young person, it is anticipated that the ICL may meet with younger children in person, thus enabling their involvement in the process, whereas older children and young people may prefer email or telephone to be the primary mode of communication. Legal Aid NSW also stated that it is not their policy for ICLs to ensure that a third person is in attendance during in-person meetings. Legal Aid Queensland's Best Practice Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers also indicate an expectation that ICLs will arrange to meet with the relevant child or young person where practical and appropriate, and it is preferred that these meetings take place in the presence of the family consultant, family report writer or other like professional involved with their case (see Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 41).

13 Note that while there were insufficient survey responses from professionals in Western Australia to analyse this issue on a quantitative basis, qualitative data collected from interviews and open-ended text box responses suggest that the more common practice in WA is for ICLs to rely on social science experts to provide evidence of the views of the child or young person (see Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 52).

14 The concept of "communities of practice" involves two aspects in the context of this study. The first refers to practice approaches emerging in particular states or territories that involve the conceptualisation of the participation function as either a collaborative task between the ICL and family consultant (or single expert) or as a task for which the ICL is responsible. The second refers to the context in which the ICL practises; that is, whether they practise exclusively in family law or in both the family law and child protection jurisdictions (see also Kaspiew et al., 2013, p. 40).

References

- Kaspiew, R., Carson, R., Moore, S., De Maio, J., Deblaquiere, J., & Horsfall, B. (2013). Independent Children's Lawyer Study: Final report (1st ed.). Canberra: Attorney-General's Department. Retrieved from <www.ag.gov.au/FamiliesAndMarriage/Families/FamilyLawSystem/Pages/Familylawpublications.aspx>.

- Legal Aid Queensland. (2014). Best practice guidelines for independent children's lawyers (ICLs) working with people who have experienced domestic violence. Brisbane: Legal Aid Queensland. Retrieved from <tinyurl.com/oqpuebu>.

- National Legal Aid. (2013). Guidelines for Independent Children's Lawyers. Canberra: National Legal Aid. Retrieved from <www.nationallegalaid.org/assets/Family-Law/ICL-Guidelines-2013.pdf>.

- Parkinson, P., & Cashmore, J. (2008). The voice of the child in family law disputes. Sydney: Oxford University Press.

- Ross, N. (2012). The hidden child: How lawyers see children in child representation (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Sydney, Sydney.

Dr Rachel Carson is a Research Fellow, Dr Rae Kaspiew is a Senior Research Fellow, Sharnee Moore is a Research Fellow, Julie Deblaquiere is a Senior Research Officer, John De Maio is a Research Fellow and Briony Horsfall was, at the time of writing, a Research Officer, all at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Carson, R., Kaspiew, R., Moore, S., Deblaquiere, J., De Maio, J., & Horsfall, B. (2014). The role and efficacy of Independent Children's Lawyers: Findings from the AIFS Independent Children's Lawyer Study. Family Matters, 94, 58-69.