Implementation in action

A guide to implementing evidence-informed programs and practices

June 2019

Jessica Hateley-Browne, Lauren Hodge, Melinda Polimeni, Robyn Mildon

Download Practice guide

Overview

Implementation is both a science and an art. It's the active process of integrating evidence-informed programs and practices in the real world (Rabin & Brownson, 2018). Implementation focuses on 'how' a program or practice will fit into and improve a service (Burke, Morris, & McGarrigle, 2012).

We've written this guide to help you implement evidence-informed programs and practices in the child and family service sector. We encourage you to use it in conjunction with the recommended tools and resources highlighted throughout the guide.

Tools and checklists

- Implementation stages – Deciding where to start tool (Appendix A) [PDF 106.41 KB]

- Implementation progress checklist (Appendix B) [PDF 81.21 KB]

- Implementation considerations checklist (Appendix C) [PDF 67.89 KB]

- Readiness Thinking Tool® (Appendix D) [DOC 48.2 KB]

- Implementation plan template (Appendix E) [DOC 77.01 KB]

List of abbreviations

AIFS Australian Institute of Family Studies

CEI Centre for Evidence and Implementation

CFIR Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

R=MC2 Readiness = Motivation x General-Capacity x Specific-Capacity

Glossary

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Acceptability | The perception that a program or practice is agreeable, palatable or satisfactory. |

| Appropriateness | The perceived fit, relevance or compatibility of a program or practice. |

| Evidence-informed programs and practices | Programs and practices that integrate the best available research evidence with practice expertise, and the values and preferences of clients. |

| Feasibility | How successfully a program can be implemented or used within your setting. |

| Fidelity | The degree to which a program or practice was delivered as intended. |

| Implementation | A process that uses active strategies to put evidence-informed approaches into practice. It is the process of understanding and overcoming barriers to adopt, plan, initiate and sustain evidence-informed programs and practices. |

| Implementation barriers | Implementation barriers make the implementation process more challenging. |

| Implementation enablers | Implementation enablers increase the likelihood a program or practice will be successfully implemented. |

| Implementation plan | A document that specifies what implementation strategies are being used, how they will be actioned, when, and by whom. |

| Implementation outcome | The effect of using implementation strategies to implement new programs, practices and services. It is different to a client outcome. |

| Implementation science | The study of how to improve the uptake of research findings and other evidence-informed practices into 'business as usual'. It aims to improve the quality and effectiveness of human services. |

| Implementation strategy | A technique that enhances the adoption, planning, initiation and sustainability of a program or practice. It is the 'how to' component of implementing a new program or practice. |

| Program outcome | A specific change expected in the target population as a result of taking part in a program. |

| Randomised controlled trial | A research design that allocates participants at random. This design aims to reduce selection bias and produce high-quality evidence. |

| Reach | How well a program or practice has been integrated into an agency or service provider, including the target population. |

| Sustainability | The extent to which a program or practice has become incorporated into the mainstream way of working, rather than being added on. |

1. Introduction

1.1 What is the purpose of this guide?

Implementation is both a science and an art. It's the active process of integrating evidence-informed programs and practices in the real world (Rabin & Brownson, 2018). Implementation focuses on 'how' a program or practice will fit into and improve a service (Burke, Morris, & McGarrigle, 2012).

We've written this guide to help you implement evidence-informed programs and practices in the child and family service sector. We encourage you to use it in conjunction with the recommended tools and resources highlighted throughout the guide.

We developed this guide using best-practice recommendations from implementation science. It uses a staged implementation process to guide your implementation activities (Metz & Bartley, 2012; Metz et al., 2015). The guide outlines all stages and steps briefly, and provides links to useful online resources.

Our guide aims to:

- increase awareness about implementation science

- explain how high-quality implementation works

- explain why implementation science is important

- equip agencies and service providers to use implementation strategies

- explain how to adapt program or practice implementation strategies for different contexts

- explain how to monitor and measure implementation outcomes

- share useful tools and resources.

It also helps you to:

- explore different types of evidence-informed programs and practices

- decide if you're ready to implement a program or practice

- identify implementation enablers and barriers

- identify and use implementation strategies

- initiate and refine your implementation process

- sustain and scale-up programs and practices.

1.2 Who is this guide for?

We wrote this guide for child and family service agencies, and their staff. It is relevant for both large and small implementation initiatives.

Our guide may help:

- agencies and service providers that are planning to implement a new program or practice

- agencies and service providers that would like to refine or sustain an existing program or practice

- staff with varying levels of experience, including frontline practitioners; their team leaders and managers; senior leaders in the organisations; and those who design or develop programs in the child and family service setting.

1.3 How should I use this guide?

You can use this guide to help you adopt, plan, initiate and maintain an evidence-informed program or practice in the child and family services sector.

The guide has different sections explaining the different stages of implementation. Depending on where you're at in your implementation process, it may not make sense for you to follow the process exactly as outlined in this guide. You can 'dip in' to the different sections of the guide based on what information you need. However, if your agency or service provider is new to implementation science - or has limited experience implementing evidence-informed programs or practices - you'll probably benefit from reading the whole guide.

2. What is implementation science?

Implementation science is the study of methods and strategies to promote the uptake of evidence-informed practices into 'business as usual', with the aim of improving service quality (Eccles & Mittman, 2006). Evidence-informed programs and practices are incorporated into 'business as usual' at very different speeds and there is often a gap between what we know works and what's being done in practice. There are many reasons for this. Sometimes the research is difficult to access and translate into a real-world environment; sometimes the evidence-informed program or practice is not a good fit for the local context; sometimes the service provider or staff are not interested in making changes to how they work; and sometimes there are barriers relating to the broader operating context, such as funding models. The field of implementation science aims to close this gap between research and practice.

2.1 Why is good implementation important?

When your program or practice implementation is high-quality, the children and families receiving your services are more likely to benefit from your service.

Many agencies and service providers now try to select and deliver programs and practices using the best available research evidence (i.e. those proven to be effective, based on well-designed evaluation studies) and best practice. Having an effective program or practice is necessary for good client outcomes. However, it is not sufficient. Using programs and practices with a strong evidence base is important, but two common pitfalls contribute to their potential not being realised:

- only focusing on 'what' program or practice to use, and ignoring 'how' the program or practice will be implemented

- failing to consider influencing factors (such as enablers and barriers) that impact your ability to initiate and sustain the program or practice.

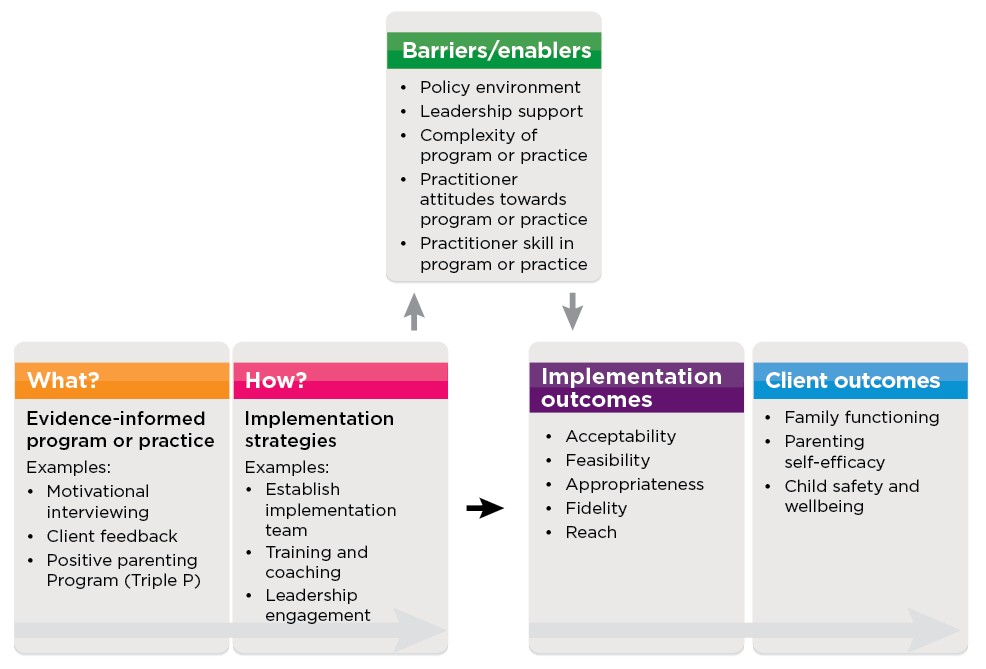

You need to consider all these factors - the 'what', the 'how' and the influencing factors - to achieve the best outcomes for children and families, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Factors to consider when improving client outcomes

2.2 What are the key concepts of implementation science?

This section explains some key concepts of implementation science. We'll highlight key ideas, themes and assumptions used throughout this guide.

Implementation frameworks

Implementation frameworks explain the different stages and activities you'll use when implementing a program or practice. They provide a map and shared language for the implementation process. Many are applicable across a wide range of settings - though some are better for particular types of interventions, or focus on different aspects of implementation. During the past 20 years, researchers have developed many implementation frameworks (Albers, Mildon, Lyon, & Shlonsky, 2017; Moullin, Sabater-Hernández, Fernandez-Llimos, & Benrimoj, 2015; Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2012).

Our guide outlines an implementation framework that integrates relevant concepts that are common across existing frameworks frequently used in the child and family service sector (see Chapter 3 for more information).

Implementation stages

Implementation happens in stages. It is a process that unfolds - it's not a single event. Your implementation model should guide you through the different steps in your implementation process. It should help you decide when to focus on each implementation activity - though the exact order of activities should not be fixed. Ideally, you should tailor your implementation process to your needs and context. And while implementation does happen in stages, the stages don't always end exactly as another begins. The process isn't always linear. For example, timeline and funding pressures may mean that you need to move fast and cause stages to overlap (with activities from two different stages happening at the same time). You may also experience setbacks that mean you need to revisit a previous stage before you can progress further. For example, staff turnover may mean you no longer have enough practitioners trained in the program or practice, resulting in a 'pause' on service delivery while you recruit and/or train additional staff.

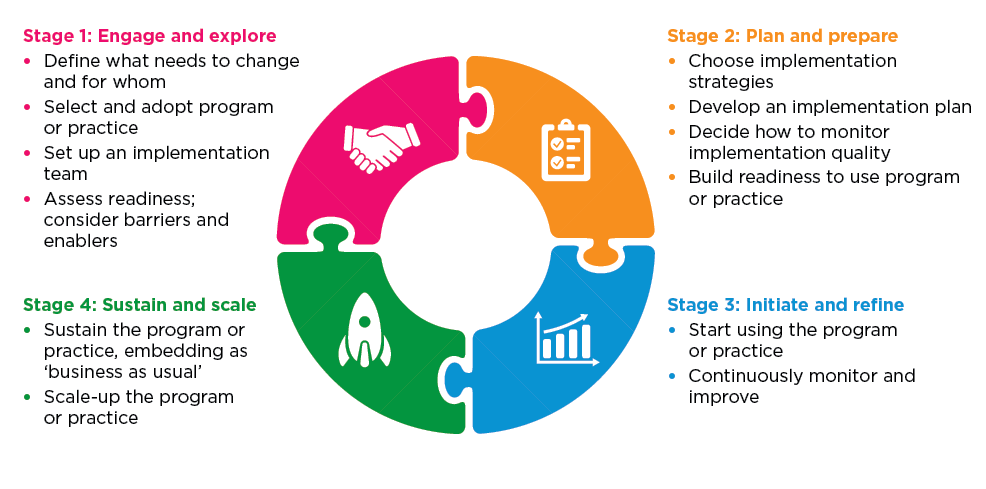

This guide outlines four stages (see Chapter 3 for more information):

Implementation enablers and barriers

Implementation enablers increase the likelihood a program or practice will be successfully implemented. Enablers can include support from an organisation's leadership, and the program or practice being a good fit for target children and families.

Implementation barriers make the implementation process more challenging. Barriers can include a lack of resources to deliver a program or practice, and low confidence in the program or practice among the people delivering it. However, you shouldn't give up on your implementation simply because you face barriers. It's normal to experience barriers. Your implementation will be successful if you can identify and overcome barriers early in the process. You should continually monitor the enablers and barriers, as different influencing factors will emerge during different stages of implementation. The process of assessing and identifying enablers and barriers is described in Chapter 4.

Implementation strategies

Implementation strategies are techniques that improve the adoption, planning, initiation and sustainability of a program or practice (Powell et al., 2019). They are the 'how to' components of the implementation process and are used to overcome barriers.

So how do you decide which implementation strategies to use? Sometimes there is existing evidence showing which implementation strategies are likely to be useful for implementing your particular program or practice. Or, if you're implementing a manualised program (i.e. a program which has been developed with a structured, detailed manual that you usually need to buy a license for), the program developers may require you to use particular implementation strategies. If you don't have any suggested implementation strategies, you can tailor your strategies based on the barriers you've identified and experienced in your program or practice.

For example, in Stage 1 (engage and explore) a key barrier may be a lack of information about the needs of the children and families who participate in your service. You can overcome this barrier by compiling agency or service provider data, such as demographics; client goals at baseline; child and family feedback; and outcomes for families when they exit your program. During Stage 2 (plan and prepare), when you've already decided what to implement, a barrier might be that staff lack the right experience and skills to implement the new program or practice. You can overcome this by providing staff with interactive, skills-based training and post-training technical assistance, such as coaching.

Chapter 5 explains how to identify and choose implementation strategies.

Implementation pace and planning

We don't provide a recommended timeline for a high-quality implementation process, as it always varies depending on your circumstances and context. However, it often takes two to four years for a well-structured program to be fully implemented. The timeline and duration of your implementation process will depend on the complexity and adaptability of your program or practice; the context of your implementation; and other influencing factors, such as policy and funding priorities.

It's important for your agency or service provider to prioritise your implementation planning and preparation activities. Common pitfalls include:

- not investing enough time or resources during the early stages of implementation

- attempting to implement too many new programs and practices at once

- not reprioritising resources from an 'old' to a 'new' initiative.

Investing adequate time and resources during the early stages of implementation will reduce your efforts later down the track. This short-term pain will result in long-term gain.

Implementation leaders and champions

Implementation leadership is the level of support leaders provide to implementation efforts. Leadership can come from people who have formal organisational authority and can mandate and create change (including executive leaders, middle management and team leaders), as well as from champions of the specific program or practice who have informal influence in the organisation (including practitioners or other staff). The benefits of having implementation leaders and champions are undisputed and should not be underestimated (Aarons, Ehrhart, & Farahnak, 2014; Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Hurlburt, 2015; Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Sklar, 2014; Aarons et al., 2016). Effective implementation requires support, involvement and communication from leadership. Leaders define the vision for your implementation. They also set expectations for staff behaviours and performance; allocate resources for your implementation efforts; and determine how the implementation is perceived throughout your organisation.

Indicators of high-quality implementation

To see how well your implementation process is going, you need to monitor your 'implementation outcomes' (Proctor et al., 2011). Implementation outcomes are the effects of using your implementation strategies. They are indicators of the quality of implementation. For example, you can monitor how acceptable your program or practice is to staff who are delivering it; how feasible the program or practice is in your context; and the fidelity of program delivery (i.e. whether the program has been implemented as intended. See Chapter 5.3 for more detail). Figure 2 illustrates the relationships between the 'what' (the evidence-informed program or practice), the 'how' (implementation strategies), and implementation and client outcomes.

In summary, using relevant implementation strategies will improve the quality of your implementation (as shown by improved implementation outcomes). This, in turn, improves client outcomes. This shows just how important it is to monitor implementation quality, as well as client outcomes.

Consider this scenario: You evaluate a new program by assessing the outcomes for children and families, and you find no beneficial effects. Unless you also assess the implementation outcomes, it's unclear if the program had no effect because it was poorly implemented (e.g. lack of program buy-in or fit; or program components were skipped or not delivered as intended), or because it's a truly ineffective program.

Figure 2: The relationships between implementation strategies, implementation outcomes and client outcomes

Source: Adapted from Lewis (2017), Lyon and Bruns (2019), Proctor et al. (2011)

3. Overview of implementation stages

Implementation is a process and it unfolds over a series of stages (Figure 3). Different implementation activities are relevant during each stage.

Depending on where you're at in your implementation process, it may not make sense for you to follow every step in every stage, as outlined here. Consider which activities you've already completed, what decisions have already been made and what makes sense in your context. You may skip some steps or start at a later stage. Use the Implementation Stages - Deciding Where to Start tool (Appendix A, PDF 106.41 KB) to help you determine where you are up to, and which stage and step should come next. You can also use the Implementation Progress Checklist to monitor your progress through the stages (Appendix B, PDF 81.21 KB).

Figure 3: Stages of implementation

Stage 1: Engage and explore

Define what needs to change and for whom: Is there a need or gap in your service? Who is affected by this need or gap? Identify what these gaps are, then decide what outcomes you'd like from a new program or practice.

Select and adopt a program or practice: Look for existing programs and practices that could fill your gap. Ensure they can meet your needs, can create the desired outcomes, are a good fit for your context and are supported by evidence.

Set up an implementation team: Consider establishing a team that's responsible for moving the program or practice through the stages of implementation.

Consider likely enablers and barriers, and assess readiness: Identify enablers and barriers to implementation that will occur early in the process, (noting enablers and barriers will need to be continuously monitored throughout the stages). Focus particularly on the ways in which your organisation is ready - and unready - to implement the program or practice.

Stage 2: Plan and prepare

Choose implementation strategies: Decide which implementation strategies are best to drive the implementation process at each stage.

Develop an implementation plan: Develop an implementation plan that identifies how to put your implementation strategies into action. Carefully plan what needs to be done; when and where it needs to happen; how it is to happen; and who is responsible.

Decide how to monitor implementation quality: Identify the best indicators of implementation quality. Plan how you will measure and monitor these during the implementation process.

Build readiness to use the program or practice: Ensure your organisation will be ready to start using the program or practice. Use implementation strategies such as training, acquiring resources and adapting existing practices.

Stage 3: Initiate and refine

Start using the program or practice: The first practitioners start using the program or practice.

Continuously monitor and refine: Use continuous quality improvement cycles to monitor the quality of the implementation. Use this information to guide improvements or adaptations to your implementation.

Stage 4: Sustain and scale

Sustain the program or practice: Improve and retain your staff's competency levels. Ensure your program or practice is embedded into 'business as usual'.

Scale-up the program or practice: If the first implementation attempts are stable, introduce the program or practice to new teams, sites or contexts. This begins a new implementation process.

4. Stage 1: Engage and explore

An implementation process begins with an exploration of your current practices and context, and a consideration of what needs to change to improve outcomes for children and families. During this stage, you also identify potential solutions to bring about your desired changes.

During this stage, your aim is to make an informed decision about which evidence-informed program or practice to adopt. You also need to assess your organisation's readiness to implement this program or practice. As you move through this process, engage as many internal stakeholders as possible. Consider running workshops or other collaborative activities to explore their insights and understand their preferences and experiences.

To make good decisions about what program or practice to implement, you need to consider:

- the needs of the target population participating in your service

- the outcomes you'd like to achieve with and for children and families

- your agency or service provider's capacity to implement the new program or practice

- the evidence proving the effectiveness of the program or practice you plan to implement.

4.1 Define what needs to change and for whom

Before you select your new program or practice, identify your target population and assess their needs. Focus on the needs that are not being met by existing services. To avoid duplicating services within a region, identify the needs not currently being met by any service - not just your own. A service-mapping exercise can aid in this process. This exercise requires you to systematically review the service providers in your area and describe what they offer your target population.

To assess the needs of the target population, use data that indicate the intensity of the problem. Involve all relevant stakeholders who can help find solutions, including people from other service providers in your region. This exercise helps to identify and define the problem you're trying to solve with your new initiative.

Next, identify the outcomes you'd like the new initiative to bring about for children and families. These should be measurable changes or benefits that are experienced as a result of your new program or practice. The outcomes should relate to the problem you defined at the start of this step. For example, if the problem was defined as children living in an unsafe home environment, relevant outcomes might include a decrease in child injuries and adequate stimulation for children in the home environment. This process helps you to narrow down the possible programs or practices under consideration. Using a program logic can help, as it draws out the relationships between program or practice inputs (e.g. resources), outputs (e.g. key activities) and outcomes (e.g. benefits for children and families). Refer to the Child Family Community Australia guidance for developing a program logic for more information.1

Table 1 provides example questions that you can use when defining your target population, their needs and the desired outcomes.

| Define the target population |

|---|

| Will you work with children, youth, parents, carers or the family unit? |

| What are their key characteristics (e.g. age, geography, culture, ethnicity and family structure)? |

| What are their strengths? |

| What problems do they face? |

| What are the main factors contributing to these problems? |

| Define the needs |

| What are you (and others in your region) currently doing to address the problems defined above? |

| Which problems are not being effectively addressed? What are the gaps in service provision? |

| Do you have data that can help you see whether existing services (yours and others) are effectively addressing these problems or not? |

| Considering the above answers, what emerges as the key problem or challenge? |

| What setting is best suited to addressing this problem (e.g. intervention in the home, school or community)? |

| Define the desired outcome |

| What benefits do you hope your clients experience as a result of a new initiative? |

| What changes do you hope to see for your clients as a result of the new initiative? |

Using an outcomes framework can help you identify and describe which outcomes you'd like to create. Examples include the NSW Government Human Services Outcomes Framework and the Victorian Public Health and Wellbeing Outcomes Framework.

4.2 Select and adopt an evidence-informed program or practice

Your next step is to identify existing programs or practices that have been proven to effectively address your problem and bring about the desired outcome. Consider where you might find these programs or practices. There are several menus and repositories of evidence-informed programs and practices,2 and these can help you identify available interventions. The program or practice also needs to be:

- a good fit for your context. Ideally, it has been shown to work for your target population, in a similar setting.

- feasible. Your agency or service provider is able to obtain the necessary resources (e.g. funding, staff, meeting rooms, vehicles) and capacity (e.g. relevant expertise, referral sources) to implement the program or practice.

You can use the Implementation Considerations Checklist tool (Appendix C, PDF 67.89 KB) to guide decision makers through the selection and adoption process.

The Implementation Considerations Checklist tool ( Appendix C, PDF 67.89 KB) can help you select a program that's appropriate and feasible for your context.

4.3 Set up an implementation team

Your implementation team will champion and drive your implementation process. It's an internal team and its purpose is to move the new program or practice through the implementation stages. It also solves problems that arise due to implementation barriers. Establishing well-informed and collaborative implementation teams (sometimes referred to as 'coalitions') can help your organisation to commit to high-quality implementation of programs and practices (Brown, Feinberg, & Greenberg, 2010).

Should I establish an implementation team?

It isn't always feasible or desirable to establish an implementation team. This may be due to staffing limitations, time restrictions, and external or executive decisions. However, implementation teams may be useful in these circumstances:

- Where the new program or practice is complex or is a significant shift away from current practice.

- Where the implementation of the program or practice impacts staff from different parts of the organisation (or across multiple sites).

- Where it's unclear who's responsible for implementing the program or practice.

Table 2 presents an overview of the implementation team's purpose, composition and core capabilities.

| Purpose | Composition and capabilities |

|---|---|

| Composition Representatives from various levels of staff within the organisation, including:

Core capabilities

|

Over time, the work of the team will be refined. The tasks and composition of the team can change as the implementation stages progress. Be prepared to change the membership of the implementation team over time, as needed. Consider:

- What core competencies are needed to drive the implementation at each implementation stage?

- Who has the skills, knowledge and decision-making authority to effectively facilitate the necessary implementation activities?

- Which internal stakeholders need to be included?

- What organisational systems and policies are needed to support implementation?

Other considerations

When you're establishing your implementation team, it's essential to invest time in the initial implementation team planning. You'll need to:

- select team members

- ensure the team has the appropriate authority to implement changes and make decisions 'in the room' to improve implementation

- develop accountability mechanisms, including tracking actions and scheduling regular meetings.

4.4 Consider likely enablers and barriers, and assess readiness

Explore possible enablers and barriers

Early in the process, it's helpful to consider likely enablers and barriers to implementation. You can start doing this when you're familiar with the program or practice you want to implement.

You should continue to monitor enablers and barriers throughout the implementation process, as different opportunities and challenges are likely to emerge as the process unfolds. However, starting now will help you identify and address early barriers that could slow down the process and reduce momentum. It will also help you to nurture the enablers which will help the new program or practice to flourish.

Some enablers and barriers will be obvious. For example, you may have a clear mandate from senior leadership to use whatever resources it takes to initiate your new program. Or, conversely, you might not have enough funding to support the program you've selected. Or, practitioners may need to be upskilled in the new practice you are seeking to implement. Other enablers and barriers will be less obvious, though no less important.

You may find it helpful to take a structured approach when assessing enablers and barriers. This approach can guide your thinking and help you to clearly see the obstacles to overcome and the existing enablers to be maintained. One common approach for exploring enablers and barriers is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., 2009).

The CFIR identifies five domains that will influence your implementation process:

- characteristics of the program or practice itself (e.g. adaptability and cost)

- individuals involved in implementation (e.g. knowledge and beliefs about the program or practice)

- the inner context or setting (e.g. organisational culture and leadership engagement)

- the outer context or setting (e.g. client needs, and policy and funding priorities)

- the implementation process (e.g. planning, reflecting and evaluating).

The CFIR website3 describes the factors that influence implementation within each domain. It also contains tools for identifying the specific enablers and barriers in each domain.

You can use the CFIR Interview Guide Tool4 to build a set of questions to guide your discussions. These can also help you to assess the enablers and barriers that are most important in your setting. The questions can be used for interviews with staff and they can guide the implementation team's discussions, as well as discussions with other decision makers during the implementation process.

Assess organisational readiness

Organisational readiness is an important aspect of your implementation. It is a key potential barrier (or enabler) to consider at this early stage of implementation. It will help you know where to focus your efforts in the next stage.

Organisational readiness refers to the extent to which your organisation is willing and able to implement the selected program or practice (Scaccia et al., 2015). Low organisational readiness is a common barrier at this stage of implementation. However, it's important to understand that 'readiness' is not a static condition. Your organisation does not have to be 100% 'ready' at the very beginning of the implementation process. Some aspects of readiness may not be present at first, but you can use implementation strategies to build them later. Readiness may also decrease over time; for example, if key staff leave your organisation. You can reassess your level of readiness at particular points during the implementation process and this can further inform your decisions on what support or change is needed. For example, the very end of Stage 2 is a good time to reassess readiness to check if the organisation is ready to initiate the practice.

A framework or tool can be useful to help to guide your assessment of organisational readiness. The Readiness = Motivation x Capacity (General) x Capacity (Specific) framework (or R=MC2; Scaccia et al., 2015) describes three factors that influence organisational readiness for implementation:

- the motivation of agency or service provider staff to implement the program or practice

- the general capacities of an agency or service provider

- the program- and practice-specific capacities needed to implement the intervention.

You can assess these three components using the Wandersman Center’s Readiness Thinking Tool® (see Appendix D, DOC 48.2 KB). This tool helps you to consider whether the different components are strengths or challenges for your organisation. The tool also provides suggested discussion questions to help you respond to your readiness assessment findings. The goal of this process is to identify how you can improve organisational readiness and enhance the likelihood of implementation success.

1 aifs.gov.au/cfca/expert-panel-project/program-planning-evaluation-guide/plan-your-program-or-service/how-develop-program-logic-planning-and-evaluation

2 Several such menus exist; for example, Communities for Children Facilitating Partners Evidence-based Programme Profiles (apps.aifs.gov.au/cfca/guidebook/), the Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook (guidebook.eif.org.uk/), and the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (www.cebc4cw.org/)

3 cfirguide.org/constructs/

4 cfirwiki.net/guide/app/index.html#/

5. Stage 2: Plan and prepare

During Stage 2, the implementation team (or other decision makers) will plan and prepare for implementation. During this stage, you'll need to:

- choose implementation strategies

- develop and start using your implementation plan

- identify your implementation outcomes

- decide how to monitor the implementation process.

5.1 Choose implementation strategies

Implementation strategies are the 'how to' of implementation. You'll use these strategies to overcome barriers, build readiness and drive the implementation process. Choose the best strategies for your context, and the program or practice you're implementing. Some interventions, such as manualised programs, come packaged with specific implementation strategies; for example, training requirements and quality monitoring. However, even these usually have scope to add other implementation strategies at the local level if you need them. Other programs or practices will not suggest which implementation strategies to use, so you'll need to choose them yourself.

If you're able to choose your own implementation strategies, one useful technique is to match the strategies to the implementation barriers you've identified or experienced. The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project identified more than 70 commonly used implementation support strategies that can be used to drive the implementation process (Powell et al., 2015; Waltz et al., 2015). See Table 3 for some examples. These strategies have been matched with common implementation barriers (defined using the CFIR) to create a decision aid - the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool.

| Implementation strategy | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Access new funding | Access new or existing money to help implement the program or practice. |

| Alter incentive structures | Develop and use incentives to support, adopt and implement the program or practice. |

| Audit and provide feedback | Collect and summarise performance data over a specified time period. Give the data to practitioners and administrators to monitor, evaluate and modify behaviour. |

| Change physical structure and equipment | Adapt physical structures and/or equipment (e.g. changing the layout of a room or adding equipment) to best accommodate the program or practice. |

| Conduct educational meetings | Hold meetings with different stakeholder groups (e.g. providers; administrators; other organisational stakeholders; and community, client, and family stakeholders) to build awareness, inform them and educate them about the innovation. |

| Conduct local consensus discussions | Talk with local providers and other relevant stakeholders to determine if the chosen problem is important to them and whether they think the new program or practice is appropriate. |

| Conduct ongoing training | Plan for and conduct ongoing training in the program or practice. |

| Develop and use tools and processes to monitor implementation quality | Develop tools and processes to monitor implementation quality (as assessed against your implementation outcomes). Use them to create your continuous quality improvement cycle. |

| Develop and distribute educational materials | Develop and distribute manuals, toolkits and other supporting materials that help stakeholders to learn about the program or practice, and that teach practitioners how to deliver the program or practice. |

| Identify and prepare champions | Identify and prepare people who'll dedicate themselves to driving an implementation. They will help to support, market and overcome indifference or resistance within the organisation. |

| Increase demand | Attempt to influence the market for your new program or practice. Increase competition intensity and increase the maturity of the market for your new program or practice. |

| Inform local opinion leaders | Identify local opinion leaders or other influential people and inform them about the program or practice in the hope they will encourage others to adopt it. |

| Make training dynamic | Vary your training methods to cater for different learning styles and work contexts. Ensure your training is interactive. |

| Mandate change | Ask your leadership team to publicly declare that the new program or practice is a priority and they're determined to implement it. |

| Model and simulate change | Model or simulate the changes that the implementation will require. |

| Provide follow-on technical support | Provide practitioners with ongoing coaching or clinical supervision. Use modelling, feedback and support to help them apply new skills and knowledge in practice. |

| Promote adaptability | Identify how a program or practice can be tailored to meet local needs. Clarify which elements to maintain to preserve fidelity. |

| Recruit, designate and train for implementation | Recruit, designate and train for the implementation effort. |

| Remind practitioners | Develop reminder systems that help practitioners to remember important information. This system can also prompt them to use the program or practice, or to do other important implementation activities. Reminders could be client- or encounter-specific, and they can be provided verbally, on paper or electronically. |

| Revise roles | Shift and revise staff roles. Consider redesigning job characteristics. When you revise roles, consider if they need to expand to cover both implementation and provision of the program or practice. Also consider how to eliminate service barriers to care, and include personnel policies. |

| Use an implementation advisor | Seek guidance and support from an implementation expert. |

| Train-the-trainer | Train designated team leaders, practice leads and partner organisations on how to train others in the program or practice. |

Source: Powell et al., 2015

You can use the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool5 to help you decide which implementation strategies to use. Input the implementation barriers you've identified into the tool and it will generate a list of implementation strategies that experts think will best address these barriers.

Sometimes the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool will generate a long list of potential strategies for addressing the inputted barriers, and these won't all be feasible in your context. While helpful, the Matching Tool can't replace careful thought and decision making based on your specific context. We've identified some guiding principles to help you select the best implementation strategies for your context:

- Select implementation strategies that best describe the change in behaviour you require to overcome the barriers you identified in Stage 1.

- Engage stakeholders (practitioners, leadership, clients, referrers and the community) to help you select the best implementation strategies and develop actions for these strategies. Consider asking stakeholders to rate the importance and feasibility for proposed implementation strategies to help you make the decision.

- Remember that implementation strategies can be one discrete action, or a collection of actions that are interwoven, packaged up and aimed at addressing multiple barriers (Powell et al., 2012).

Once you've chosen your implementation strategies, develop specific actions to bring them to life. Table 4 provides examples of common barriers to implementation, and relevant strategies and actions that can be used in the child and family services context to overcome each of the barriers.

The table can also be viewed on pages 17–19 of the PDF.

| Barrier | Implementation strategy | Definition | Relevant implementation stage(s) | Example actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low adaptability A program or practice seems promising but has been developed for a different context and target population. It's not appropriate in its current form due to cultural, linguistic and other reasons. | Promote adaptability | Identify how to tailor the program or practice to meet local needs. Clarify which elements of the program or practice must be maintained to preserve fidelity. | Stage 1: Engage and assess Stage 4: Sustain and scale |

|

| Resistance to change Practitioners aren't committed to the change because they don't believe a new program or practice is needed. | 1. Conduct local consensus discussions 2. Conduct educational meetings 3. Identify and prepare champions | 1. Talk with stakeholders about whether the chosen problem is important to them and what program or practice is appropriate to address it. 2. Meet with stakeholder groups and tell them about the program or practice. 3. Identify and prepare people who can motivate colleagues, model effective implementation and overcome resistance to change. | Stage 1: Engage and assess Stage 2: Plan and prepare | 1. (a) Conduct workshops with practitioners and ask for their thoughts on how to define the target population, their unmet needs, and how to explore new programs or practices that might meet their needs. (b) Conduct group discussions with practitioners and leadership staff using the questions in the Implementation Considerations Checklist (see Appendix C , PDF 67.89 KB). 2. Run group or one-on-one information sessions with staff and practitioners. Explain the program or practice, including potential benefits and the resources and commitment required. Give your staff the opportunity to ask questions and explore their concerns. 3. During consultations, identify possible implementation champions. Approach them afterwards and chat with them about the positive behaviours you observed. Try to enlist their support in the implementation process. |

| Low engagement from leadership Key managers are not committed to, or actively involved in, the implementation process. | Recruit, designate and train for leadership | Recruit, designate and/or train leaders to drive the implementation process | Throughout the whole implementation process | Implementation leaders need to continuously communicate the vision, purpose and expectations for program implementation. Their aim is to inspire and encourage staff to adopt the new way of working. You may need to:

|

| Limited evaluation of the implementation process | 1. Develop and use tools and processes for monitoring implementation quality 2. Audit and provide feedback | 1. Develop tools and processes for monitoring the quality of the implementation, according to the implementation outcomes. Use these to inform your continuous quality improvement cycle. 2. Collect and summarise performance data over a specified time period. Give it to practitioners and administrators to monitor, evaluate and modify behaviour. | Develop in Stage 2: Plan and prepare Use in Stage 3: Initiate and refine Stage 3: Initiate and refine | 1 & 2 Plan how to collect and monitor data that can inform your decisions about how to improve practice or implementation processes. The data should show if the program or practice is being used, how well it's being used, if it's being used with fidelity; that is, as intended, the quality of the implementation process, and the impact of the program or practice on clients. You should decide and put into practice:

|

| Low self-efficacy Practitioners are not confident in their own ability to implement and deliver the program or practice to a high standard. | 1. Conduct ongoing training 2. Make training dynamic 3. Provide follow-on coaching | 1. Plan for and conduct ongoing training in the program or practice. 2. Vary your training methods to cater to different learning styles and work contexts. Ensure your training is interactive, with a focus on skill-building. 3. Use skilled coaches to provide ongoing modelling, feedback and support for staff. These coaches help staff apply their new skills and knowledge in practice. They can be either internal or external to your organisation. | Stage 2: Plan and prepare & Stage 3: Initiate and refine Stage 2: Plan and prepare Stage 3: Initiate and refine | 1. Ensure all practitioners, team leaders, supervisors and managers can access training in an ongoing way. Consider incentivising participation. 2. Use adult learning principles to design training in the new program or practice. Consider using web-based technology to reach a broader audience and make the delivery more flexible. 3. Training alone is usually not sufficient to create a change in practice. Supplement training with follow-on coaching by experts in the program or practice. This will help practitioners to turn their new knowledge into practice. Training takes place at the end of Stage 2 and coaching can start at Stage 3. Consider a coach-the-coach model. In this model, an expert gives intensive coaching to an existing team leader or supervisor, who in turn coaches the practitioners in their team. |

5.2 Develop an implementation plan

It's important to plan your implementation carefully. Planning will help you identify and address many of the common barriers before they start to cause issues. It will also help you to establish the right implementation strategies to overcome or minimise the barriers. The implementation plan is best developed collaboratively by those on your implementation team (or other key decision makers if you have not set up a team). You can amend and adapt the plan over time. You may need to reconsider your priorities as conditions change and new barriers emerge. The implementation plan can also be used to record implementation enablers, ensuring there is a plan in place for maintaining them throughout implementation.

Your implementation plan should include:

- the implementation barriers (identified in Stage 1)

- the implementation strategies and specific actions you will take to overcome each of the barriers (chosen in Stage 2)

- who will deliver on each action

- timeframes, milestones and due dates for each action.

Depending on your needs, your implementation plan may also include:

- a record of implementation enablers, and strategies and actions for how to maintain them

- a register of all the risks you've identified during implementation

- an implementation quality monitoring plan (described in Chapter 5.3)

- an activity tracker (to track the progress of your implementation strategies and actions)

- any other information that can help guide your process.

You can use the Implementation Plan Template ( Appendix E) [DOC 77.01 KB] to help the implementation team or other decision makers to map out their plan. For another example, see this template developed by the National Clinical Effectiveness Committee.6

5.3 Decide how to monitor implementation quality

The only way to know if your implementation is going well is to monitor its progress. This needn't be an onerous task. Firstly, you'll need to decide which data will be most useful. Choose data that will show when you need to adjust and improve the implementation process, or your new program or practice. You'll also need to ensure you collect and review data regularly. The best implementation monitoring plans use continuous quality improvement cycles during Stage 3 - once you've started the new practice or program (see Chapter 6.3). Ideally, they should also help you identify any unintended consequences (both positive and negative), which can inform future implementation efforts, such as scaling-up to other teams or sites (see Chapter 7.2).

Your implementation monitoring plan should track your key implementation outcomes (i.e. is the program being implemented and how well?). These are different to your program outcomes, which describe the desired changes for children, parents, carers, families and caregivers (i.e. is the program making a difference for people using the service?). Implementation outcomes indicate the quality of your implementation. An evidence-informed program or practice that's implemented well (i.e. has good implementation outcomes) has the best chance of delivering benefits for children and families (see Figure 2 in Chapter 2).

Your implementation team or other decision makers should select which outcomes to monitor, ideally before the new program or practice has started. However, if the program or practice has already started, it's not too late to put monitoring measures in place. You can do this any time.

Table 5 includes some key implementation outcomes, alongside some simple, good-quality measurement methods and tools. We also encourage you to consider additional outcomes and measures that are appropriate for your context.

It's important to consider the quality of your measurement tools. This includes psychometric considerations such as reliability, validity and sensitivity, as well as practical considerations such as length, language and ease of use.

| Implementation outcome | Definition | How to measure |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | The perception among stakeholders that a program or practice is agreeable, palatable or satisfactory |

|

| Feasibility | The extent to which the program or practice can be successfully used or carried out within your setting |

|

| Appropriateness | The perceived fit, relevance or compatibility of a program or practice |

|

| Fidelity | The extent to which a program or practice is being delivered as intended |

|

| Reach | The degree to which a program or practice is integrated into an agency or service provider setting, including the degree it effectively reached the target population. |

|

Your fidelity measures should be tailored to the program or practice you're implementing. The EPIS Centre website provides examples of existing fidelity measures for a range of programs in the child and family service sector. The best fidelity measures or checklists allow for assessment of how often the program or practice is used, and how extensive its reach is. They also track the competence and quality of program or practice use.

The Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC) is currently developing a repository of tools that measure implementation outcomes. The repository includes information on the psychometric properties (e.g. reliability, validity) and pragmatic qualities of each tool. The repository is a work in progress and available to paid members of SIRC.

Table 5 includes three short, simple and freely accessible implementation outcome measures with good psychometric properties: AIM (to measure acceptability), FIM (to measure feasibility) and IAM (to measure appropriateness). All three have been developed and validated by Weiner and colleagues (2017) and are available as a free download.7

5.4 Build readiness to use the program or practice

Now it's time to build your organisation's readiness to implement the program or practice. Start using the implementation strategies and activities in your implementation plan that are relevant at this early stage. Some strategies, such as ongoing and skills-based training and identifying and preparing champions, will need to be used during Stage 2 so you can start to build readiness before you start the program or practice. You may also need to use other strategies in your implementation plan later in the implementation process (e.g. follow-on coaching, which would only start after the program or practice has been initiated in Stage 3).

6. Stage 3: Initiate and refine

During Stage 3, you'll start using the program or practice for the first time. By this point, staff will be trained in the program or practice, and the necessary systems to support your implementation will be established (e.g. the plan for data collection and monitoring; leadership engagement; and support). It's very important to collect and respond to the monitoring data in this stage. You'll need to focus on continuously improving the implementation of the program or practice and responding to the new implementation barriers that emerge as you begin using the program or practice. Try to identify and respond to these barriers in a timely way.

6.1 Initiate the program or practice

Practice is initiated when the first practitioners have started using the new program or practice. You may choose to initiate your program or practice with just one team or a small number of teams. In the early days, even your highly experienced staff may feel challenged because the program or practice itself, or the implementation activities, may be unfamiliar. They may perceive the new program or practice to be unhelpful, or even burdensome.

If your implementation plan includes post-training implementation strategies, such as follow-on coaching, they should be actioned now.

6.2 Continuously monitor the implementation process

Now it's time to start monitoring implementation quality, according to the plan you made in Stage 2 (see Chapter 5.3). You should also continue to look for new enablers and barriers to implementation (see Chapter 4.3 for some suggestions for how to do this). Use the information from your quality monitoring to help you decide if you need to review your implementation strategies and how you might do that. Share summaries of your monitoring data at your implementation team meetings (or meetings with other decision makers) and identify and explore barriers regularly together. This will ensure the information you collect gets used to inform decisions on how to improve the implementation process. It will also ensure any unintended consequences from implementing the new program or practice are noticed, reviewed and responded to. This could include staff burnout as a result of feeling over-stretched, and unexpected costs being incurred during implementation.

Be curious about the information and data you're collecting. The purpose is not to judge whether the implementation 'succeeded' or 'failed'. Rather, the purpose is to bring some of the barriers to light so you can respond to, minimise or overcome them.

6.3 Make improvements based on monitoring data

Regularly review your monitoring data. Your reviews may show that some implementation strategies or actions in the implementation plan (see Chapter 5.2) don't meet your needs and should be adjusted. This is a normal part of the implementation process. For example, you may find that you need to provide top-up training or more intensive coaching in the program or practice to help practitioners to build their skills and confidence. Or, you may find that referral rates are slowing down and you need to undertake more promotion and educational outreach activities to boost referral numbers.

When you identify barriers, draw on the resources of the implementation team or other decision makers to decide how to respond to them and improve your implementation process. Use your data to inform your decisions about how to make improvements. Once you've decided how to revise your implementation strategies, update your implementation plan to record the new actions you've committed to. Remember to note who will be responsible for each action and when each action is due to be completed.

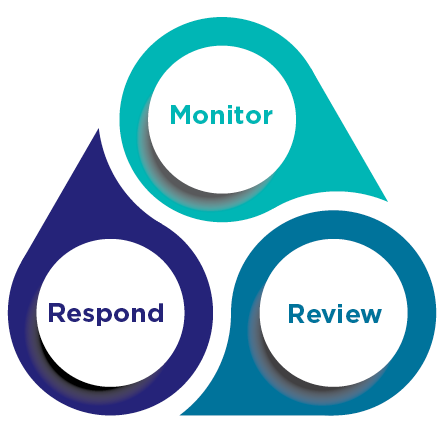

It's important to keep monitoring implementation quality, enablers and barriers after introducing potential solutions. If nothing changes, you know the 'solution' you introduced is not working. You'll need to try a new implementation strategy or revisit your understanding of the barrier you're trying to overcome. Figure 4 illustrates this continuous quality improvement cycle.

Figure 4: Continuous quality improvement cycle

Applying this cycle during implementation will help you to quickly determine whether you need to make changes to the program or practice to improve the fit between your context, and the new program or practice. As you become more familiar with the improvement cycle, data-informed decision making will become easier and more natural. What may have felt challenging at the beginning of this phase will likely become routine.

Consider this example

A plan is developed to implement and monitor a new parenting program for families at risk of government child protection services involvement. The program is implemented and administrative data are collected to monitor whether the target population is being reached (monitor). After a few months of program implementation, the administrative data show the parenting program is not reaching the intended target population of families; however, enrolment targets are being met (review). The implementation team investigates why this is the case; however, they need more information.

They can gather this information by reviewing the cases accepted at intake and discussing the issue with relevant staff. Questions arise, like: Are the external referrals into the program inappropriate, but being accepted at intake anyway? If so, they may need to ensure there's clearer communication with external stakeholders and undertake additional promotion of the program. Or perhaps practitioners are self-selecting 'easy' children and families for the program, and putting those who reflect the true target population on a wait list? This may suggest that practitioners aren't confident with the new approach. They may need additional encouragement (e.g. praising efforts) and support (e.g. reduced caseload or administrative duties) from leadership, or more intensive coaching to build confidence in the program elements (respond).

This example shows how implementation teams can make data-informed decisions to effectively address barriers that can threaten high-quality implementation. Once you decide how to respond, you'll need to update and action your revised plan. Then the cycle starts again.

6.4 Adapt the program or practice

If you choose to adapt your program or practice at this stage, ensure you take a very considered approach. First, get a clear sense of the 'core components' versus the 'flexible components' of the program or practice you're using. Core components directly reflect the underlying theory and mechanisms of change that the program was built on, and cannot be changed. Flexible components are not directly related to the theory and mechanism of change, and may offer scope for local adaptations. We suggest you seek advice from the program developer or purveyor about which components are core and which are flexible before embarking on an adaptation process.

There is some evidence to suggest local adaptations may be beneficial to implementation, encouraging buy-in and ownership, and enhancing the fit between an intervention and the local setting (Lendrum & Humphrey, 2012). However, too much flexibility can take away from a program's effectiveness, particularly when modifications are made to the core components of the intervention. If you find lots of adaptations are needed to fit your context, you may want to revisit your initial decision to adopt that particular program or practice.

Practitioners can feel frustrated when they're delivering manualised programs with many fixed, core components. These types of programs can be perceived as inflexible and you may find program fidelity (i.e. delivering the program exactly as it was designed and intended) pitted against a practitioner's sense of autonomy and 'practice wisdom'. However, it can be more helpful to view program fidelity as a guide to understanding where to be 'tight' and where to be 'loose'. Practitioners should stick tight to the core components of an intervention until they fully understand them, and can apply and use them in daily practice. Only then should you begin to introduce local adaptations. A good fidelity measure will enable you to actively and accurately monitor the core components and will show you when adaptations can be introduced.

Core components may include the content and mode of delivery of a program. Flexible components may include the program packaging and promotional material, which can be adapted to use different languages and images that best reflect the local context.

7. Stage 4: Sustain and scale

During this stage, you'll aim to achieve 'full implementation'. This means your practitioners routinely apply the program or practice, and it's integrated into 'business as usual'. There are no fixed rules defining exactly when scale-up should take place, although we've outlined several considerations below.

7.1 Sustain the program or practice

Your program or practice can be considered sustainable when it becomes an integrated or mainstream way of working. It's sustainable when it's embedded as 'business as usual' and is part of routine practice; when it's no longer a 'new' or 'extra' part of your service delivery. You know your program or practice is sustainable when practitioners no longer revert to old ways of working or previous levels of performance, and don't drop core elements of the implementation process over a sustained period of time (e.g. two years). However, this doesn't mean your implementation efforts stop. During this stage, you should:

- continue to apply your continuous quality improvement processes, ensuring your data remain relevant and useful

- use relevant implementation strategies to ensure consistent quality of implementation (e.g. ongoing coaching)

- acknowledge and reward good implementation efforts.

Sustainment requires adequate and ongoing funding. It requires a good program or practice-context fit, and sufficient capacity to train new and replacement staff. It also requires ongoing support and stable stakeholder commitment. Constant change is a normal part of the child and family service sector, so it's important to ensure you're always ready to adapt to change. This means you need to consider sustainment from the very beginning of your implementation process.

7.2 Scale-up the program or practice

When you successfully implement a new program or practice, it can create great enthusiasm in organisations and communities, and should be celebrated. As you will know by this stage, implementing a new program or practice isn't always easy! Success can spur decision makers into expanding the program or practice. They may choose to implement it at a greater scale in identical, or slightly different, contexts. Both situations require cautious decision-making, guided by questions like:

- Did we achieve the implementation and client outcomes we intended? Does our data support this?

- Have these outcomes been positive and stable over time?

- Do we expect major changes to the current implementation context within the foreseeable future (e.g. policy or funding reform)?

If the answers to these questions indicate the initial implementation is stable, it may be natural to scale up or out.

Scaling is the process of implementing the same program or practice to other teams, sites, service providers or agencies. You should try to use the lessons you learned from the initial implementation process to identify potential enablers and barriers during expansion, as well as predict which implementation strategies you require. It can help to revisit the implementation plan from your initial implementation to review the barriers you identified, encountered and overcame at each stage, including any unintended consequences of implementation that needed to be addressed along the way.

Scaling up or out can be like an entirely new implementation process. It will lead your organisation back to some of the steps in earlier implementation stages, starting a new implementation process. For example, organisational readiness should be assessed with each new team or site, as their context and resources may differ. You'll probably need a separate implementation plan for each new implementing team or site.

If you plan to scale up the program or practice across a service system, ensure it's not mandatory for all sites and isn't tied to compliance requirements. Implementation of the program or practice will be most successful if the potential implementation sites have agency over the decision, and if they believe the approach will be beneficial.

Implementation teams and other implementation champions will be important resources during this stage. They can inform and guide the scaling process. Similarly, coaches who supported local implementation efforts and helped practitioners to learn and acquire new skills can help to share their skills and knowledge on a broader scale.

8. A note of encouragement

Using good implementation practices can seem like a lot of work - and in many ways they are. They require careful planning, thoughtfulness, resourcefulness and dedication. However, even though high-quality implementation takes time and effort, this investment of resources pays dividends later - in the form of more sustainable and effective service delivery for children and families. For further help, you can access implementation support from a number of specialist organisations.

When you use the principles and processes outlined in this guide, you'll become more familiar with what's required to achieve high-quality implementation. Actively using this guide will help you turn your knowledge of the concepts into practical skills. Try applying the implementation framework outlined in this guide to your next initiative. See what fits in your context, and what activities or approaches may need to be adapted or tailored. By using this approach step by step, you'll build your confidence and capacity to lead implementation efforts in your context, for the ultimate aim of improving outcomes for the children and families using your service.

References

- Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., & Farahnak, L. R. (2014). The implementation leadership scale (ILS): Development of a brief measure of unit level implementation leadership. Implementation Science, 9(45).

- Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., Farahnak, L. R., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2015). Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): A randomized mixed-method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implementation Science, 10(11).

- Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., Farahnak, L. R., & Sklar, M. (2014). Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 255-274.

- Aarons, G. A., Green, A. E., Trott, E., Willging, C. E., Torres, E. M., Ehrhart, M. G. et al. (2016). The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: A mixed-method study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 991-1008.

- Albers, B., Mildon, R., Lyon, A. R., & Shlonsky, A. (2017). Implementation frameworks in child, youth and family services - Results from a scoping review. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 101-116.

- Brown, L. D., Feinberg, M. E., & Greenberg, M. T. (2010). Determinants of community coalition ability to support evidence-based programs. Prevention Science, 11(3), 287-297.

- Burke, K., Morris, K., & McGarrigle, L. (2012). An Introductory Guide to Implementation. Dublin: Centre for Effective Services.

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(50).

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1).

- Lendrum, A., & Humphrey, N. (2012). The importance of studying the implementation of interventions in school settings. Oxford Review of Education, 38(5), 635-652.

- Lewis, C. (2017). What are implementation mechanisms and why do they matter? Paper presented at the 2017 Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC) Conference, Seattle, WA.

- Lyon, A. R., & Bruns, E. J. (2019). From evidence to impact: Joining our best school mental health practices with our best implementation strategies. School Mental Health, 11(1), 106-114.

- Metz, A., & Bartley, L. (2012). Active implementation frameworks for program success. Zero to Three, 32(4), 11-18.

- Metz, A., Bartley, L., Ball, H., Wilson, D., Naoom, S., & Redmond, P. (2015). Active implementation frameworks for successful service delivery: Catawba County Child Wellbeing Project. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(4), 415-422.

- Moullin, J. C., Sabater-Hernández, D., Fernandez-Llimos, F., & Benrimoj, S. I. (2015). A systematic review of implementation frameworks of innovations in healthcare and resulting generic implementation framework. Health Research Policy and Systems, 13(16).

- Powell, B. J., Fernandez, M. E., Williams, N. J., Aarons, G. A., Beidas, R. S., Lewis, C. C. et al. (2019). Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: A research agenda. [Perspective]. Frontiers in Public Health, 7(3).

- Powell, B. J., McMillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., Carpenter, C. R., Griffey, R. T., Bunger, A. C. et al. (2012). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical Care Research and Review, 69(2), 123-157.

- Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M. et al. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(21).

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A. et al. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65-76.

- Rabin, B., & Brownson, R. (2018). Terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In R. C. Brownson, G. A. Colditz & E. K. Proctor (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (Vol. 2, pp. 19-45). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Scaccia, J. P., Cook, B. S., Lamont, A., Wandersman, A., Castellow, J., Katz, J. et al. (2015). A practical implementation science heuristic for organizational readiness: R=MC2. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(4), 484-501.

- Tabak, R. G., Khoong, E. C., Chambers, D. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2012). Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(3), 337-350.

- Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Matthieu, M. M., Damschroder, L. J., Chinman, M. J., Smith, J. L. et al. (2015). Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science, 10(109).

- Weiner, B. J., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C., Powell, B. J., Dorsey, C. N., Clary, A. S. et al. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12(108).